Abstract

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) derivatives were conjugated onto the Cys-34 residue of human serum albumin (HSA) to determine their effects on the solubilization, permeation, and cytotoxic activity of hydrophobic drugs such as paclitaxel (PTX). PEG(C34)HSA conjugates were prepared on a multigram scale by treating native HSA (n-HSA) with 5- or 20-kDa mPEG-maleimide, resulting in up to 77% conversion of the mono-PEGylated adduct. Nanoparticle tracking analysis of PEG(C34)HSA formulations in phosphate buffer revealed an increase in nanosized aggregates relative to n-HSA, both in the absence and presence of PTX. Cell viability studies conducted with MCF-7 breast cancer cells indicated that PTX cytotoxicity was enhanced by PEG(C34)HSA when mixed at 10:1 mole ratios, up to a two-fold increase in potency relative to n-HSA. The PEG(C34)HSA conjugates were also evaluated as PTX carriers across monolayers of HUVEC and hCMEC/D3 cells, and found to have nearly identical permeation profiles as n-HSA.

Keywords: albumin, drug delivery, polyethylene glycol, protein modification, site-specific ligation

INTRODUCTION

Protein function and recognition can be rationally modified by the covalent ligation of molecular structures such as optical tags1, targeting ligands2, carbohydrates3, and polymers.4,5 However, coupling methods that rely on available amines or carboxylic acids for amide bond formation typically have poor regioselectivity, and can result in intra- or intermolecular crosslinks that lead to protein denaturation, aggregation, or general loss of function.6 Site-specific ligation methods are highly desirable for introducing additional functionality to proteins without disrupting other physicochemical properties. A useful alternative to amide bond formation involves the chemoselective addition of alkylmaleimides to exposed cysteines.7 This method of conjugation has little to no effect on the electrostatic surface potential of proteins at physiological pH, and is thus less likely to induce unintended changes in secondary or tertiary structure. N- and C-modified proteins have the intrinsic drawback of having different net charges relative to the native protein, which can affect their conformational behavior, dispersion stability, aggregation kinetics, biomolecular recognition, and catalytic activity.6,8,9

PEGylation (i.e. the ligation of one or more polyethylene glycol chains to external residues) is a widely used tactic to modify the pharmacokinetic properties of drug carriers10,11 and protein-based biologics.12,13 Covalently attached PEG chains can stabilize proteins by providing a surrogate hydration shell,14 or prevent denaturation by limiting conformational freedom.15 While much attention has been paid to antibodies and other “functional” biomolecules, passive proteins such as human serum albumin (HSA) are also important candidates because of their putative roles in drug solubilization and delivery. HSA’s native role as a plasma carrier makes it an ideal candidate for transporting hydrophobic drugs that possess higher binding affinities from the bloodstream into extravascular tissue space.16,17 HSA is thought to facilitate drug permeation by passing through endothelial layers via caveolar-mediated transcytosis.18,19 As one of most abundant proteins in the plasma (35–50 mg/mL),20 HSA forms aggregates reversibly and can accumulate passively in tumor tissue due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.21,22 In this regard, we note that HSA-based formulations have been characterized as nanoparticles ex vivo, but are thought to disperse into monomeric form soon after entering the bloodstream.23 This suggests that the pharmacokinetic properties of HSA may be tailored by judicious structural changes.

Interest in albumin-based drug delivery has been increasing due to the favorable pharmacology of HSA, its low immunogenicity, and its current availability in recombinant form. A well-known example of albumin-based formulation is HSA-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane®), currently being used for the treatment of several late-stage cancers.24,25,26 Paclitaxel (PTX) is a powerful antimitotic that induces apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells;27 however, its therapeutic efficacy has been compromised by poor water solubility or by surfactants with peripheral side effects (e.g., Cremophore EL).28,29,30 The clinical success of Abraxane® confirms the benefits of HSA as a carrier of poorly soluble drugs like PTX; nevertheless, adverse side effects such as moderate neuropathy and neutropenia persist,26,31,32 indicating the need to further optimize drug loading and delivery.

PEGylated HSA has been prepared by conventional amide ligation, and shown to provide significant enhancements in its pharmacokinetic profile for drug delivery.33 However, most studies have been conducted by modifying the acidic or basic residues on albumin, and the poor regioselectivity of amide-based ligations render these formulations vulnerable to unintended changes in structure or colligative properties. For example, N-PEGylation reduces the volume of the hydrophobic binding cavity in the second R-helix domain, despite overall retention of HSA size and shape.34

Both HSA and its congener bovine serum albumin (BSA) possess a free thiol residue at Cys-34, which presents the option of site-specific S-PEGylation using maleimide chemistry.35,36 S-PEGylation of albumins can be performed with minimal perturbation to pre-existing disulfide bridges with subsequent retention of protein structure, as demonstrated in the case of PEG-(C34)BSA,35 and can increase its circulation lifetime relative to unmodified albumins, as demonstrated in a rat model with PEG(C34)HSA.36 These reports indicate that S-PEGylation at Cys-34 is an appealing alternative to amide-based ligations for developing albumin-based carriers with tailored pharmacological properties. It is worth mentioning that maleimide-based reagents have also been developed for PEGylation across disulfide bonds,37,38 but are not immediately relevant for proteins bearing free thiols.

In this article we characterize the carrier properties of two mono-PEGylated HSA derivatives with site-specific conjugation at Cys-34, prepared on a multigram scale using maleimide-terminated mPEG chains having molecular weights of 5 and 20 kDa. S-PEGylation produces minimal perturbations in conformation or solubilization of PTX, but significantly increases HSA’s propensity to self-assemble into protein nanoparticles as characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). We also investigate the permeation of PTX through monolayers of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) and brain microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) with and without PEG(C34)HSA conjugates, and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of PTX-loaded PEG(C34)HSA against MCF-7 breast cancer cells relative to native HSA (n-HSA). We find that C34-PEGylation has essentially no negative impact on PTX loading and subsequent permeation across cell monolayers. On the other hand, PEG(C34)HSA conjugates provide substantial increases in the transport and cytotoxicity of PTX delivered to MCF-7 cells, with negligible toxicity from PEGylated HSA alone.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Characterization of PEGylated HSA Adducts

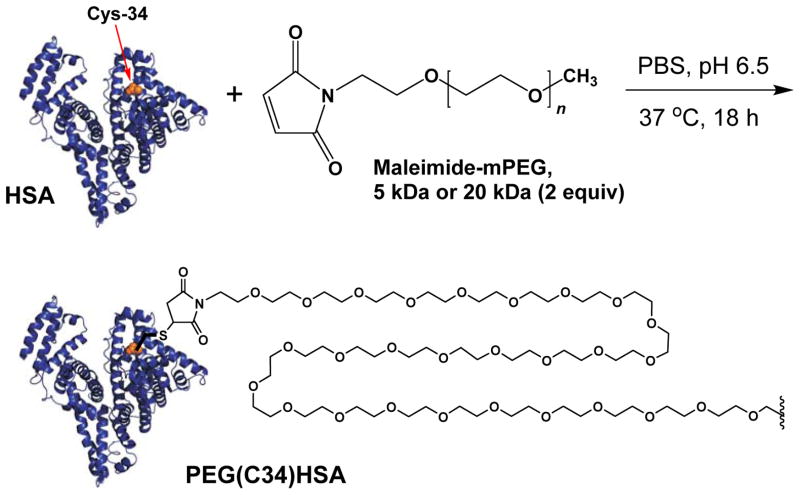

Following an earlier reported procedure,36 PEG(C34)HSA adducts were prepared at 37 °C in mildly acidic PBS (pH 6.5) by combining n-HSA (25 mg/mL) with 2 or 4 equivalents of 5-kDa or 20-kDa mPEG-Mal (Scheme 1). Maintaining a pH slightly below 7 helps to keep HSA in conformations that shield its internal disulfide bonds from other solutes.39 Analytical samples of S-PEGylated HSA were obtained by HPLC purification, whereas protein mixtures synthesized on a multigram scale were separated from unreacted mPEG-Mal by stirred ultrafiltration. Recombinant HSA was used instead of plasma-derived HSA, which reduces the risk of infection from unknown viruses or prions that may be present in the latter. Recombinant and plasma-derived HSA have been shown to be identical in structure.40

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PEG(C34)HSA using 5- or 20-kDa mPEG-maleimide (Mal); PEG chain truncated for clarity.

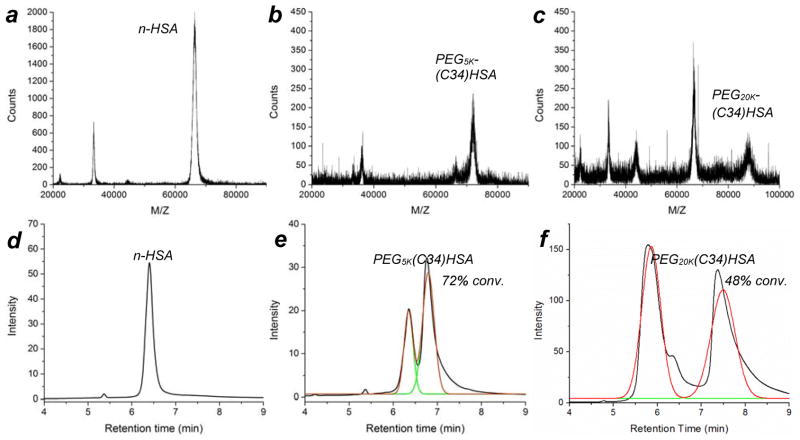

MALDI-MS and analytical HPLC were used to assess the degree of PEGylation: n-HSA produced a strong peak at m/z 66,553,41 whereas PEG5K- and PEG20K(C34)HSA produced additional peaksets centered at 71,984 (+5,431 amu) and 87,694 (+21,141 amu), respectively (Figure 1a–c). HPLC analysis on dialyzed samples indicated that treatment of n-HSA (Rt 6.4 min) with two equivalents of 5-kDa mPEG-Mal supported a 72% conversion into PEG5K(C34)HSA (Figure 1e), whereas treatment with two equivalents of 20-kDa mPEG-Mal supported a 48% conversion into PEG20K(C34)HSA (Figure 1f). The conversion efficiency was not affected by changes in reaction time, temperature or pH, but increasing the amount of 20-kDa mPEG-Mal to four equivalents increased the conversion of PEG20K(C34)HSA to 77% (Figure S3, Supporting Information). It should be noted that the HSA was not pretreated with reducing agents, which can further optimize maleimide addition to free cysteines;42 therefore, the yields reported here should be viewed as a lower limit. We also note that ultrafiltration of PEG(C34)HSA from excess mPEG-Mal on a multigram scale was initially tedious due to the high viscosity of the retentate but became more efficient after several washings, with less than 1 wt% mPEG after six cycles according to HPLC (Figure S4, Supporting Information). All subsequent studies using PEG(C34)HSA were performed with protein mixtures prepared from a 2:1 ratio of mPEG-Mal to n-HSA, and purified by six cycles of ultrafiltration.

Figure 1.

(a–c) MALDI-MS analysis of n-HSA (m/z ~66.5 kDa), PEG5K(C34)HSA (m/z ~72.0 kDa), and PEG20K(C34)HSA (m/z ~87.7 kDa); (d–f) HPLC traces of n-HSA (as received), HSA treated with 2 equiv mPEG5K-Mal or 2 equiv mPEG20K-Mal. For additional data see Figures S3 and S4, and Table S1 (Supporting Information).

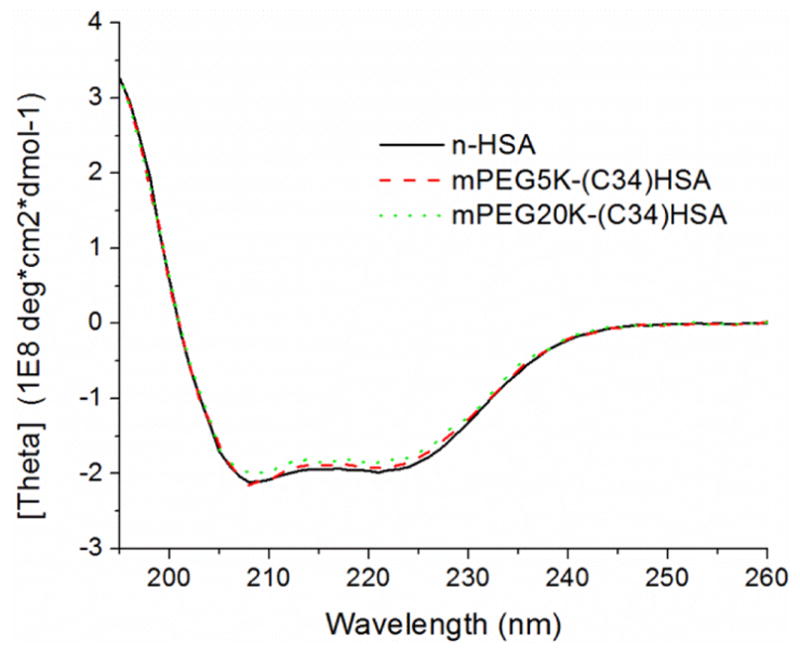

ATR-IR analysis confirmed retention of the PEG chain after exhaustive dialysis, with a strong peak at 1090 cm−1 corresponding to C–O stretching modes, and minimal differences in the amide peak region relative to n-HSA (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Circular dichroism analysis of the PEG-(C34)HSA derivatives also indicated negligible changes in secondary protein structure relative to n-HSA, with very minor perturbations in 195–260 nm region (Figure 2). We thus presume that S-PEGylation at Cys-34 has minimal influence on the secondary structure of HSA.

Figure 2.

Circular dichroism spectra of n-HSA, PEG5K(C34)HSA (72% conversion), and PEG20K(C34)HSA (77% conversion).

Effect of PTX–HSA Formulations on Cell Viability

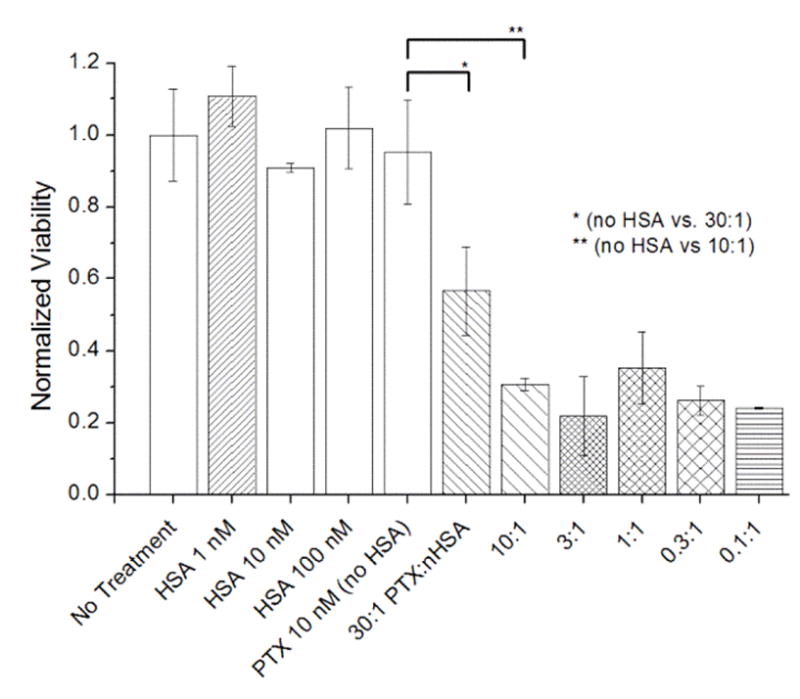

MCF-7 cells exposed to 10 nM PTX using a 30:1 mole ratio of PTX:n-HSA had a 1.7-fold greater therapeutic effect compared to 10 nM PTX in PBS without HSA (p < 0.05), whereas PTX formulated in a 10:1 mole ratio with n-HSA had 3.1-fold greater efficacy (p < 0.005; Figure 3).43 HSA without PTX (up to 100 nM) had a negligible effect on cell viability, confirming that its primary role is to increase the solubilization of PTX. The increased drug efficacy did not vary significantly for PTX:n-HSA ratios below 10:1, implying an upper limit of 10 molecules of PTX per HSA carrier.

Figure 3.

The effect of formulating PTX (10 nM) with n-HSA on MCF-7 cell cultures, 5 days post-treatment (N=3). PTX:n-HSA mole ratios range from 30 to 0.1, with [PTX] fixed at 10 nM. Significant changes in cytotoxicity marked with * (p < 0.05) or ** (p < 0.005). Error = 1 stdev.

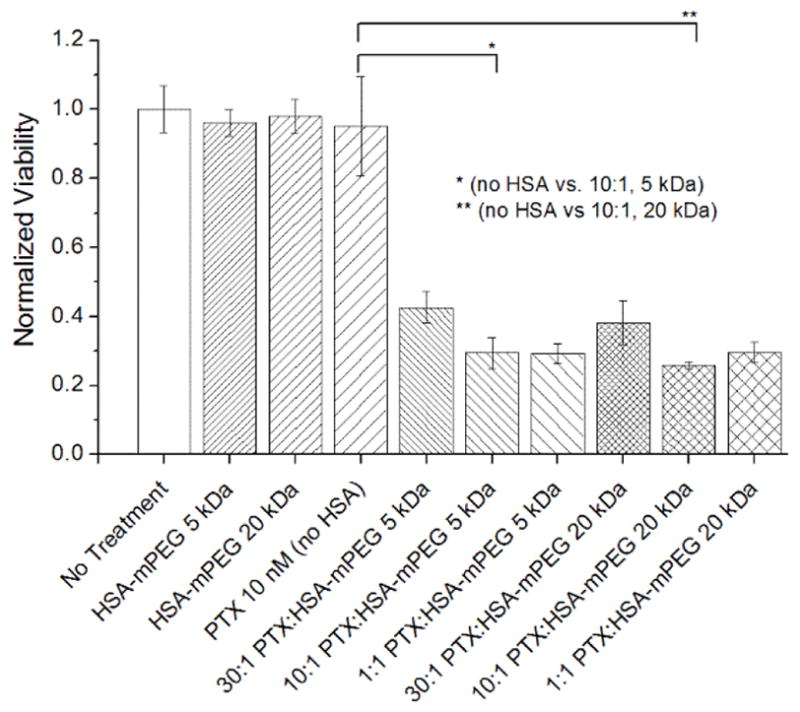

MCF-7 cells exposed to 10 nM PTX in a 10:1 mole ratio of PTX and PEG5K(C34)HSA or PEG20K(C34)HSA experienced similar increases in toxicity relative to PTX alone (Figure 4). As in the case with n-HSA, maximum efficacy was attained when PTX was formulated in a 10:1 mole ratio with PEG(C34)HSA derivatives compared to a 30:1 ratio, with no further improvements below that. These results imply that the PEG chain does not inhibit the ability of HSA to bind and release PTX. Again, control experiments indicated that PEGylated HSA derivatives have no effect on cell viability.

Figure 4.

The effects of PTX (10 nM) formulated with PEG5K(C34)HSA or PEG20K(C34)HSA on MCF-7 cell cultures, 5 days post-treatment, with [PTX] fixed at 10 nM (PTX:HSA = 30–0.1; N=3). Significant changes in cytotoxicity marked with * and ** (p < 0.005). Error = 1 stdev.

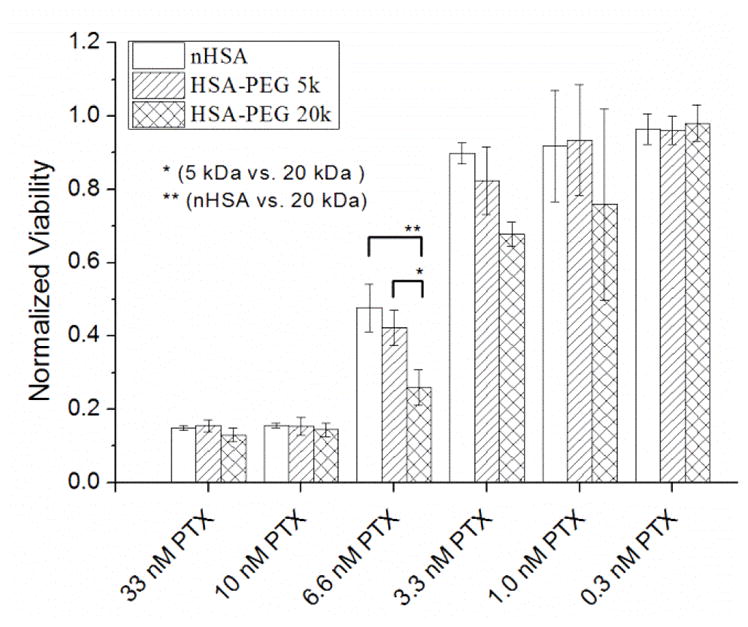

MCF-7 cells were exposed to a range of PTX doses (0.3–33 nM) formulated at 10:1 mole ratios with n-HSA, PEG5K(C34)HSA, or PEG20K(C34)HSA. For intermediate PTX doses (6.6 nM), we observed that formulations with PEG20K(C34)HSA were at least 60% more toxic than that of PEG5K(C34)HSA (p<0.05), and 80% more toxic than that of n-HSA (p < 0.01; Figure 5). A linear interpolation of cytotoxicity data at 3.3 and 6.6 nM yields IC50 values of 6.5, 5.9, and 4.7 nM when PTX is formulated respectively with 10 mol% of n-HSA, PEG5K(C34)HSA, and PEG20K(C34)HSA, with the latter providing a nearly 40% increase in acute cytotoxicity relative to n-HSA. While the basis for the greater potency provided by PEG20K(C34)HSA has not yet been elucidated, we observe an intriguing correlation with changes in the self-association behavior of HSA induced by Cys-34 tethered mPEG chains (see below).

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of PTX (0.3–33 nM) formulated in a 10:1 mole ratio with n-HSA, PEG5K(C34)HSA, or PEG20K(C34)HSA (MCF-7 cells, 5 days post-treatment; N=3). Significant changes in cytotoxicity marked with * (p < 0.05) or ** (p < 0.01). Error = 1 stdev.

Effects of PEGylation and PTX on Protein Nanoparticle Formation

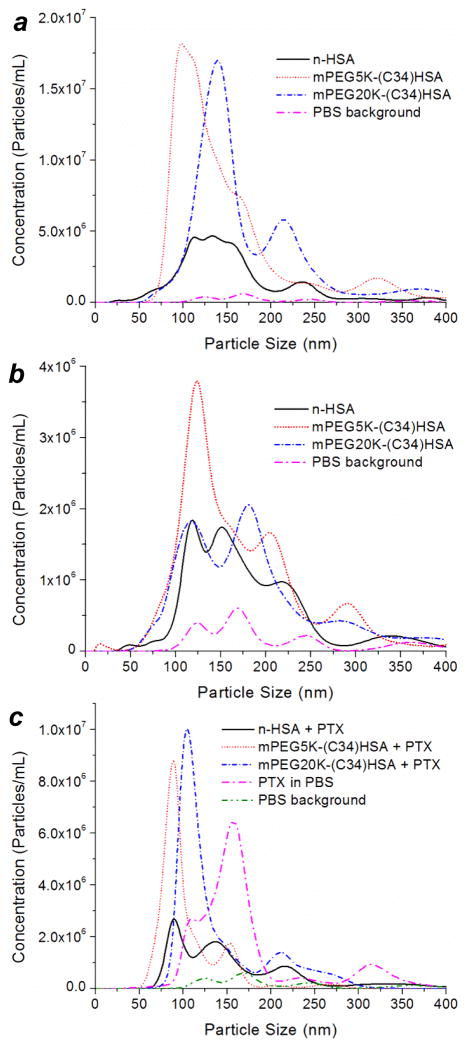

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was used to measure the hydrodynamic size (dh) and concentration of submicron protein aggregates in PBS (pH 6.5). In nearly all cases, multimodal distributions were obtained with a wide variance (range of 100–400 nm); however, a comparison between datasets revealed clear differences in population sizes. At high protein concentration (1 mg/mL or 13–15 μM), mixtures containing PEG5K- and PEG20K(C34)HSA formed several times more nanoparticles than n-HSA (Figure 6a), while their dh and volumetric mean values (dvol) remained roughly the same (Table 1). At tenfold lower concentration (0.1 mg/mL or 1.3–1.5 μM), suspensions with PEGylated HSA again showed a higher number of nano-aggregates relative to pure n-HSA (Figure 6b). Although these concentrations are substantially higher than those used in the cytotoxicity assays, they show that S-PEGylation promotes HSA nanoparticle formation. It is worth noting that dynamic light scattering analysis of PEG20K(C34)HSA at 0.01 mg/mL also indicates nanoparticle formation (dh = 30–80 nm), whereas n-HSA at the same concentration is essentially monomeric.36

Figure 6.

Hydrodynamic size analysis and number distribution of HSA nanoparticles by NTA, for mixtures comprised of n-HSA, PEG5K(C34)HSA, and PEG20K(C34)HSA in PBS. (a) 1 mg/mL (13–15 μM), (b) 0.1 mg/mL (1.3–1.5 μM), (c) 0.1 mg/mL with 10 equiv. PTX. A plot of PTX aggregates in PBS without HSA ([PTX] = 12.5 μM) is included for comparison.44

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of HSA nanoparticles by NTA.

| Sample | particle count (× 106 mL−1)a | hydrodynamic size (nm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mode peaks b | mean (dh) | RSD (%) | dvolc | RSD (%) | ||

| 1 mg/mL (no PTX) | ||||||

| n-HSA | 258 | 100–160 (broad), 235 | 162 | 48 | 200 | 43 |

| mPEG5K(C34)HSA | 745 | 100, 320 | 152 | 51 | 195 | 45 |

| mPEG20K(C34)HSA | 671 | 140, 220 | 188 | 50 | 237 | 45 |

| 0.1 mg/mL (no PTX) | ||||||

| n-HSA | 92 | 120, 150, 225, 340 | 192 | 37 | 219 | 35 |

| mPEG5K(C34)HSA | 221 | 125, 210, 290 | 166 | 48 | 206 | 43 |

| mPEG20K(C34)HSA | 157 | 120, 180, 290 | 182 | 48 | 227 | 44 |

| 0.1 mg/mL (10:1 PTX:HSA) | ||||||

| n-HSA | 123 | 90, 140, 220 | 189 | 65 | 264 | 54 |

| mPEG5K(C34)HSA | 161 | 90, 160 | 105 | 35 | 120 | 33 |

| mPEG20K(C34)HSA | 225 | 105, 210 | 141 | 43 | 173 | 40 |

| PTX, 13 μg/mLd | 215 | 110, 160, 310 | 173 | 38 | 198 | 35 |

Based on average number of tracks over three runs.

>100% above background.

Volumetric mean dvol = (Σnidi3/N)1/3, where ni is the number of particles with size di.

15 μM PTX with 1% DMSO in PBS; no HSA present.

The effects of PEGylation on the spontaneous formation of HSA nanoparticles were also evident for excipients formulated with PTX at a 10:1 mole ratio. At low carrier concentration (0.1 mg/mL), mixtures with PEG5K- and PEG20K(C34)HSA formed aggregates with a narrower, bimodal distribution relative to n-HSA (Figure 6c).44 It is worth noting that the number of n-HSA and PEG20K(C34)HSA nanoparticles increased significantly in the presence of PTX, suggesting their formation to be driven partly by the cooperative association of hydrophobic domains. These results reveal the complex interplay between protein concentration, PEG chain length, and the inclusion of PTX on the self-assembly of HSA nanoparticles in physiologically relevant conditions.

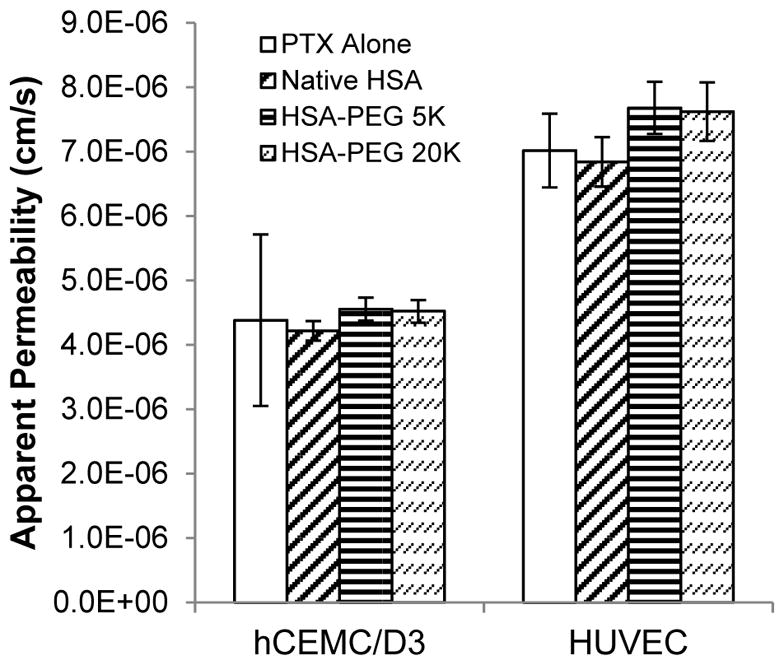

Effect of Formulations on PTX Permeability

Monolayers of HUVEC and hCMEC/D3 cells were initially tested to examine the effect of n-HSA and mPEG(C34)HSA on PTX permeability, using [14C]-labeled drug. HUVEC monolayers are used to model the peripheral vasculature, whereas the hCMEC/D3 monolayers are representative of the blood–brain barrier.45,46 Studies were run at 1 μM [14C]-PTX alone and in 10:1 mole ratio with n-HSA or mPEG(C34)HSA, preceded by a 4-hour pre-equilibration period for the cell monolayers (Figure 7).47 The HSA formulations did not produce significant differences in [14C]-PTX permeation across either cell monolayer, which suggests that the binding and permeation of free PTX may be reversible. However, HUVEC monolayers exhibited significantly faster permeability rates, implying that PTX permeates more readily into the vascular periphery relative to the brain. This is expected, as hCMEC/D3 cells express high levels of efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein that are active against PTX.48

Figure 7.

Permeability of 1 μM [14C]-paclitaxel across hCMEC/D3 and HUVEC monolayers. Studies were run in triplicate simultaneously using a 10:1 mole ratio of PTX:n-HSA or PEG(C34)HSA (error = 1 stdev).

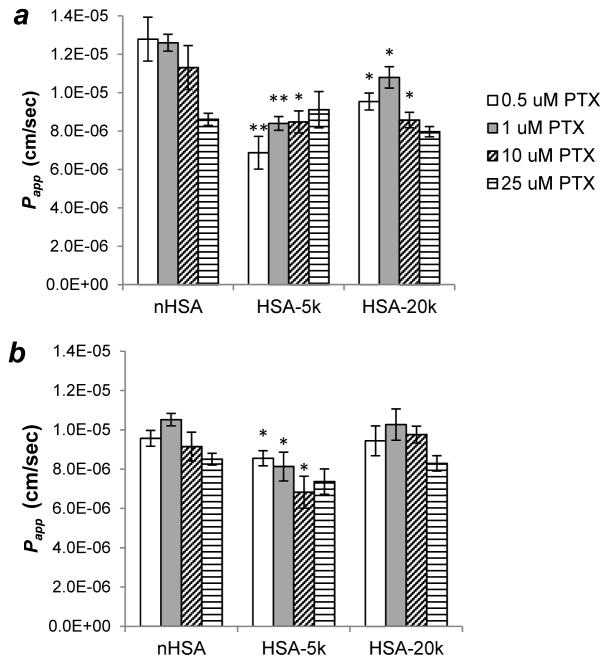

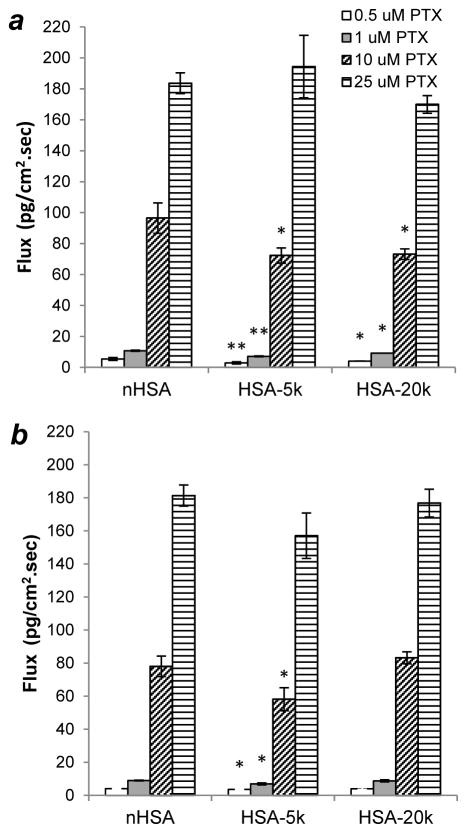

The effect of PTX concentration on HSA-mediated permeability was also investigated. Papp values across HUVEC monolayers were initially obtained at 0.5, 1, 10, and 25 μM PTX in a 10:1 mole ratio with n-HSA or PEG(C34)HSA, following pre-equilibration. Studies conducted at 0.5 and 1 μM PTX contained only [14C]-labeled drug, whereas higher concentrations were made from unlabeled drug supplemented with 1 μM [14C]PTX. At low solute concentrations, n-HSA appears to provide greater permeability then either PEG5K(C34)HSA or PEG20K(C34)HSA, but at higher concentrations no significant differences are observed (Figure 8a). The effect of drug–carrier ratio on permeability was also examined at a 5:1 ratio of PTX to n-HSA or PEG(C34)-HSA (Figure 8b). In this case, modest decreases in Papp values at higher solute concentrations were observed for all three HSA formulations, with minor differences between carrier species.

Figure 8.

Effect of solute concentration on HSA-mediated HUVEC permeability. (a) Papp of [14C]-PTX using a 10:1 mole ratio of PTX to HSA carrier; (b) Papp of [14C]-PTX using a 5:1 mole ratio of PTX to HSA carrier. Permeability studies were run in triplicate simultaneously; differences between carriers marked with * (p < 0.05) or ** (p < 0.01). Error = 1 stdev.

While Papp is useful for delineating possible changes due to partitioning, diffusivity, or variations in free drug for each formulation, it only represents average marker velocities. It is perhaps more important to consider the effects of formulation on drug flux (Papp × C0), which represents the actual amount of drug transferred across the endothelial barrier and is a reliable metric for estimating blood levels. Since flux is concentration-dependent, it better illustrates the effects of solubilizing formulations than the relatively small changes in Papp. As expected, large increases in flux are observed for both 10:1 and 5:1 mole ratios of PTX to n-HSA or its S-PEGylated conjugates (Figure 9). Again, S-PEGylation had little to no impact on drug transport, with minor differences attributable to the limited precision typically observed in permeation studies. This establishes that C34-PEGylated HSA can increase PTX efficacy as shown above, without compromising drug solubilization and permeability.

Figure 9.

[14C]-PTX flux across HUVEC monolayers using n-HSA or PEG(C34)HSA. (a) 10:1 molar ratio of PTX to HSA carrier; (b) 5:1 molar ratio of PTX to HSA carrier. Permeability studies run in triplicate simultaneously; differences between carriers marked with * (p < 0.05) or ** (p < 0.01). Error = 1 stdev.

The enhanced efficacy of PTX formulated with PEG5K- and especially PEG20K(C34)HSA is greatest near its IC50 value against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. We also observe that S-PEGylation increases the number of HSA nanoparticles (up to 1.8-fold) relative to n-HSA, particularly in the presence of PTX. While further research is needed to establish the basis for therapeutic enhancement, we consider the following as plausible factors for the observed phenomena:

While the 5- and 20-kDa PEG chain attached to Cys-34 do not disrupt the tertiary structure of HSA, they may reduce its strength of association with bound PTX by increasing its conformational lability;

Changes in the conformational stability of S-PEGylated HSA may also affect the stability of their aggregates in endosomes, with greater PTX release to the cytoplasm after uptake;

The PEG chains may promote the nano-emulsification of HSA and PTX,49 into forms that are favorably transported by albumin receptors.

In short, while the prescribed benefits of protein PEGylation such as extended stability and circulation times in the bloodstream are well appreciated,12–15 there appear to be additional factors that may contribute toward favorable pharmacokinetics and drug release profiles, and await further validation.

CONCLUSIONS

We have established that formulation of PTX with PEG5K(C34)HSA and especially PEG20K(C34)HSA enhances its acute toxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells relative to native HSA carriers, while retaining high levels of permeability across monolayers of HUVEC or hCMEC/D3 cells. The latter has important ramifications on the bioavailability of PTX administered by non-intravenous mechanisms, as well as its extravasation into diseased tissue. C34-PEGylation has a notable influence on the size distribution of HSA nanoparticles, which may be partly responsible for the increased cytotoxicity of the PTX payload. Future studies are needed to generalize the therapeutic and pharmacokinetic enhancements of PEG(C34)HSA-mediated uptake for different classes of hydrophobic drugs, as well as various cancer cell lines and animal tumor models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant HSA was obtained from GenLantis (San Diego, CA); mPEG-maleimide was obtained from Laysan Bio (Arab, AL); hydrocortisone, Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), polystyrene T-75 flasks, and Transwell® permeable supports were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Paclitaxel was obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA); radiolabeled [14C]paclitaxel ([14C]PTX) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). DMEM media, penicillin/streptomycin, and L-glutamine were obtained from Corning Cellgro (Manassas, VA); fetal bovine serum was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Atlanta, GA); MTT reagent was obtained from RPI (Mount Prospect, IL); EGM-2, EBM-2, and basic fibroblast growth factor were obtained from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). MCF-7 cells were obtained from the Purdue Center for Combinatorial Chemical Biology; HUVEC cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA); hCMEC/D3 cells were provided by Dr. Pierre-Olivier Couraud at Institut Cochin (Paris, France). Phosphate buffer solution (PBS) was prepared by tenfold dilution from a concentrated stock containing 80 g NaCl, 2 g KCl, 4 g Na2HPO4, and 2 g KH2PO4. All solutions were prepared using initially deionized water using a Milli-Q ultrafiltration system from Millipore (Bedford, MA) with a measured resistivity above 18 MΩ·cm, passed through a 0.22-μm filter to remove particulate matter.

Gram and Multigram Synthesis of PEG(C34)HSA conjugates

In a typical reaction, powdered HSA (1.0 g, 15.1 μmol) was dissolved in 40 mL of sterilized PBS (adjusted to pH 6.5) in a 100-mL glass round-bottomed flask. The PBS was passed through a 0.2-μm syringe filter prior to use, and the mixture was stirred for 15 minutes. mPEG5K -Mal (155 mg, 31 μmol) or mPEG20K-Mal (620 mg, 31 μmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of sterilized PBS (pH 6.5) and added in 1-mL portions over 1 minute to the stirred HSA solution. The mixture was placed in a 37 °C bath and stirred for 20 hours, then cooled to room temperature. Solutions of S-PEGylated HSA were transferred to dialysis membrane tubings (MWCO 12.4 kDa for PEG5K-HSA; MWCO 50 kDa for PEG20K-HSA) and gently agitated in 500 mL of deionized water to remove salts and excess mPEG-Mal (2 rounds, > 1 h each). Approximately 90% of each PEG(C34)HSA was set aside for cell culture studies; the remainder was subjected to additional dialysis for characterization. PEG(C34)HSA conjugates could be lyophilized and stored in the dark at 4 °C.

For PEG(C34)HSA conjugates prepared on a multigram scale, purifications were performed with an Amicon stirred ultrafiltration cell (180 mL) equipped with a cellulose membrane filter (100 kDa MWCO), both from Millipore. Reaction mixtures were concentrated to gelatinous slurries (ca. 10 mL) then redispersed in deionized water to maximum volume, and repeated for up to 6 cycles. The rate of filtration ranged from over 10 mL/min to under 1 mL/min, depending on the concentration of residual mPEG-Mal in the retentate.

Protein Characterization

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectra (MALDI-MS) were obtained using an Applied Biosystems Voyager DE PRO spectrometer, equipped with a nitrogen laser (337 nm) and a time-of-flight mass analyzer. Positive-ion MS were obtained in the linear mode using an accelerating voltage of 25 kV, grid voltage of 94%, and extraction delay time of 98 nsec. The m/z range for this study was 10–100 kDa, using 150 laser shots per spectrum and sinapinic acid as the matrix material.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were obtained using a Jasco J-810 spectrophotometer. Protein samples were prepared in halide-free phosphate buffer and diluted to 1 μM. The instrument was flushed with nitrogen for 1 hour prior to use; spectra were collected in triplicate from 190–260 nm at a scan rate of 7 minutes at 25 °C, with data averaging performed after background subtraction. Attenuated total reflectance infrared (ATR-IR) spectra were acquired using a Nicolet Nexus 670 FT-IR, under constant nitrogen flow. Samples were prepared by depositing 1 mL of solution onto the ATR crystal, then dried under a nitrogen stream until a thin film was obtained. The sample chamber was purged for 20 minutes prior to collecting data.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses were performed on 100-μL aliquots of PEG(C34)HSA after extensive dialysis, using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC with a Zorbax XDB-C8 column (Agilent, 4.6 mm × 15 cm). Gradient elutions were performed using 33–66% aqueous CH3CN with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min; the column was equilibrated at 33% CH3CN for at least 30 minutes prior to sample injection. Proteins were detected by absorbance at 280 nm, with yields determined by peak area integration. Levels of free mPEG-Mal were determined by HPLC at 215 nm, using a Zorbax XDB-C8 column with a gradient elution of 35–45% CH3CN plus 0.1% TFA (5-kDa mPEG-Mal), or a Phenomenex C18 reversed-phase column (2.0 mm × 5 cm) with a gradient elution of 30–90% CH3CN plus 0.1% TFA (20-kDa mPEG-Mal), with calibrations against a reference sample. In both cases, the amount of residual Mal-mPEG after six rounds of ultrafiltration was less than 1 wt% (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Particle Characterization

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was performed using a Nanosight LM-10 system equipped with a blue laser (λ= 405 nm), with data analysis supported by NTA v.2.3.5.0033 (Build 16).50 NTA was performed using PBS (pH 6.5) stored in polyethylene containers. The imaging chamber was cleaned with acetone and a microfiber cloth prior to use, then washed with particle-free water until no background signals were observed. Water was removed from the NTA chamber with a sterile plastic syringe just prior to use, and replaced with protein solution (1.0–0.1 mg/mL). Three tracking videos were collected per sample; 50 μL of fresh solution was injected in between each run to prevent protein aggregates from settling, followed by a 60-second recording at a shutter speed of 700 and a gain of 400. The number of tracks per run varied from 300 to 2000, depending on concentration. Hydrodynamic size analysis was derived from number and volume particle distributions, with population samples based on the number of tracks accumulated over several runs. Optimized parameters for video analysis (advanced mode) include a detection threshold of 10, 9 × 9 blur setting, and automated settings for track length and minimum particle size.

HSA–PTX Formulation

PTX-HSA formulations were produced from freshly prepared stock solutions of PTX in DMSO (585 μM) and PEG(C34)HSA or n-HSA in PBS adjusted to pH 6.5 (150 μM). PTX solutions were diluted serially with PBS to concentrations at 40× above the target dose. PTX and HSA stock solutions were then combined in a 1:1 v/v ratio (0.4 mL total) and allowed to stand for 4 hours at room temperature, prior to use. 10-μL aliquots of HSA–PTX solution were added to 190 μL of cell culture media in 96-well plates containing MCF-7 cells at 10–20% confluence. DMSO concentrations were 0.1% v/v or less; a flow chart describing a protocol for serial dilution is provided in Supporting Information (Figure S1).

Cell Permeation Studies

HUVEC and hCMEC/D3 cells were cultured in T-75 flasks at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 90% humidity. HUVECs were cultured in EBM-2 supplemented with Lonza EGM-2 SingleQuots®. hCMEC/D3 cells were cultured in EBM-2 supplemented with 5% FBS, 1× penicillin–streptomycin, 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, 1.4 μM hydrocortisone, 5 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 1% chemically defined lipid concentrate, and 10 mM HEPES buffer. After thawing, cells were passaged at least three times before transport studies with media changes every other day.

Transport studies were performed in the apical to basolateral direction in triplicate wells simultaneously. HUVECs were seeded between passages 6–10, while hCMEC/D3 cells were seeded at passages 34–42. Cells were seeded onto collagen-coated, 0.4-μm polyester Transwells®, at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 for HUVECs and 70,000 cells/cm2 for hCMEC/D3 cells. HUVEC and hCMEC/D3 cells were allowed to proliferate and differentiate for 7 and 14 days respectively, with exchange of cell culture media every other day. Confluent cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS then equilibrated for 30 minutes in HBSS, just prior to permeability studies. Formulations containing [14C]-PTX were added to the apical side of the Transwell® plate, which was kept on a rocker tray as aliquots were removed from the donor compartment at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 minute time points. Initial and remaining donor as well as cell lysate samples were also taken for permeability and mass balance calculations. 100 μL samples were diluted in 4 mL EcoLite® scintillation fluid and counted for 5 minutes on a Beckman Coulter LS 6500 scintillation counter. Apparent permeability (Papp) coefficients were determined using the following equation:

where dM/dt (counts/min) is the steady-state rate of mass transfer, SA (cm2) is the surface area of the apical membrane, and C0 (counts) is the initial donor concentration. Studies were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Cell Viability Assays

Mitochondrial oxidation assays using the tetrazolium dye MTT were performed as previously described51 but using MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which were cultured in T-75 flasks and complete DMEM media with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin prior to plating. In a typical experiment, 96-well microtiter plates (5,000 cells/well) were incubated overnight in 200 μL of media to approximately 10% confluence. Solutions in each well were replaced the following day with 190 μL of fresh media and 10 μL of PTX-HSA formulation, followed by 5 days of incubation at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The media was removed and replaced with 190 μL fresh media and 10 μL 0.5% MTT, incubated at room temperature for 14 hours, then replaced with 200 μL DMSO for homogenization. Absorbance measurements were recorded on a VersaMax microplate reader at 570 nm with background subtraction; cell viabilities were normalized to a negative control group (having reached 70–90% confluence over 5 days). Experiments were run in triplicate with errors representing one standard deviation; two-tailed probability values were obtained by Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Dane O. Kildsig Center for Pharmaceutical Processing Research, and by the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research (P30 CA023168). We thank Tonglei Li (Purdue University) and Pierre-Olivier Couraud (Institut Cochin, Paris, France) for their generous donations of HUVEC and hCMEC/D3 cells respectively.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION. Flow chart describing PTX-HSA formulations for in vitro toxicity study; FT-IR spectra; additional LC analysis of HSA PEGylation. These materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Karassina N, Corona C, McDougall M, Lynch DT, Hoyt CC, Levenson RM, Los VGV, Kobayashi H. In Vivo Stable Tumor-Specific Painting in Various Colors Using Dehalogenase Based Protein-Tag Fluorescent Ligands. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1367–1374. doi: 10.1021/bc9001344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson SF, Bettinger T, Seymour LW, Behr JP, Ward CM. Conjugation of Folate via Gelonin Carbohydrate Residues Retains Ribosomal-inactivating Properties of the Toxin and Permits Targeting to Folate Receptor Positive Cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27930–27935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinclair AM, Elliot S. Glycoengineering: The Effect of Glycosylation on the Properties of Therapeutic Proteins. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:1626–1635. doi: 10.1002/jps.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molino NM, Bilotkach K, Fraser DA, Ren D, Wang SW. Complement Activation and Cell Uptake Responses Toward Polymer-Functionalized Protein Nanocapsules. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:974–981. doi: 10.1021/bm300083e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monfardini C, Veronese MF. Stabilization of substances in circulation. Bioconjugate Chem. 1998;9:418–450. doi: 10.1021/bc970184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Alonso JP, Diez-García F, Font J, Ribó M, Vilanova M, Scholtz JM, González C, Vottariello F, Gotte G, Libonati M, Laurents DV. Carbodiimide EDC Induces Cross-Links That Stabilize RNase A C-Dimer against Dissociation: EDC Adducts Can Affect Protein Net Charge, Conformation, and Activity. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1459–1473. doi: 10.1021/bc9001486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalker JM, Bernardes GJL, Lin YA, Davis BG. Chemical Modification of Proteins at Cysteine: Opportunities in Chemistry and Biology. Chem Asian J. 2009;4:630–640. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broersen K, Weijers M, de Groot J, Hamer RJ, de Jongh HHJ. Effect of Protein Charge on the Generation of Aggregation-Prone Conformers. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1648–1656. doi: 10.1021/bm0612283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao JP, Yong ZH, Zhang F, Ruan KC, Xu CH, Chen GY. Positive Charges on Lysine Residues of the Extrinsic 18 kDa Protein Are Important to Its Electrostatic Interaction with Spinach Photosystem II Membranes. Acta Biochim Biophys Sinica. 2005;37:737–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:214–221. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan SM, Mantovani G, Wang X, Haddleton DM, Brayden DJ. Advances in PEGylation of important biotech molecules: Delivery aspects. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:371–383. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan R, Gaspar R. Nanomedicine(s) under the Microscope. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:2101–2141. doi: 10.1021/mp200394t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nischan N, Hackenberger CPR. Site-specific PEGylation of Proteins-- Recent Developments. J Org Chem. 2014;79:10727–10733. doi: 10.1021/jo502136n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng W, Guo X, Qin M, Pan H, Cao Y, Wang W. Mechanistic Insights into the Stabilization of srcSH3 by PEGylation. Langmuir. 2012;28:16133–16140. doi: 10.1021/la303466w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Martínez JA, Solá RJ, Castillo B, Cintrón-Colón HR, Rivera-Rivera I, Barletta G, Griebenow K. Stabilization of a-Chymotrypsin Upon PEGylation Correlates With Reduced Structural Dynamics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:1142–1149. doi: 10.1002/bit.22014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghuman J, Zunszain PA, Petitpas I, Bhattacharya AA, Otagiri M, Curry S. Structural basis of the drug-binding specificity of human serum albumin. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paál K, Müller J, Hegedûs L. High affinity binding of paclitaxel to human serum albumin. Eur J Biochem. 2001;8:2187–2191. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John TA, Vogel SM, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Quantitative analysis of albumin uptake and transport in the rat microvessel endothelial monolayer. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:187–196. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert W, Frank PG, Razani B, Park DS, Chow CW, Lisanti MP. Caveolae-deficient endothelial cells show defects in the uptake and transport of albumin in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48619–48622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters T. All about Albumin: Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratz F. Albumin as a drug carrier: design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2008;132:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsadek B, Kratz F. Impact of albumin on drug delivery — New applications on the horizon. J Control Release. 2012;157:4–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai N. Drug Delivery Report. 16. Winter. 2007/2008. Nab Technology: A Drug Delivery Platform Utilizing Endothelial gp60 Receptor-based Transport and Tumour-derived SPARC for Targeting; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai NV, Trieu Z, Yao Z, Louie L, Ci S, Yang A, Tao C, De T, Beals B, Dykes D, et al. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1317–1324. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MR, Manikhas GM, Orlov S, Afanasyev B, Makhson AM, Bhar P, Hawkins MJ. Abraxane®, a novel Cremophor®-free, albumin-bound particle form of paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kavallaris M. Microtubules and resistance to tubulin-binding agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:194–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: The drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anil KS, Alka G, Aggarwal D. Paclitaxel and its formulations. Int J Pharm. 2002;235:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marupudi NI, Han JE, Li KW, Renard VM, Tyler BM, Brem H. Paclitaxel: A review of adverse toxicities and novel delivery strategies. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;5:609–621. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aigner J, Marme F, Smetanay K, Schuetz F, Jaeger D, Schneeweiss A. Nab-Paclitaxel Monotherapy as a Treatment of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer in Routine Clinical Practice. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3407–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko YJ, Canil CM, Mukherjee SD, Winquist E, Elser C, Eisen A, Reaume MN, Zhang LY, Sridhar SS. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for second-line treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A single group, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:769–776. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dosio F, Arpicco S, Brusa P. Poly(ethylene glycol) human serum albumin–paclitaxel conjugates: preparation, characterization and pharmacokinetics. J Control Release. 2001;76:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng F, Manjula BN, Smith PK, Acharya SA. PEGylation of Human Serum Albumin: Reaction of PEG-Phenyl-Isothiocyanate with Protein. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1352–1360. doi: 10.1021/bc7003878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plesner B, Fee CJ, Westh P, Nielsen AD. Effects of PEG size on structure, function and stability of PEGylated BSA. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;7:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao T, Cheng YN, Tan HN, Liu JF, Xu HL, Pang GL, Wang FS. Site-Specific Chemical Modification of Human Serum Albumin with Polyethylene Glycol Prolongs Half-life and Improves Intravascular Retention in Mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:280–288. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumacher FF, Nobles M, Ryan CP, Smith MEB, Tinker A, Caddick S, Baker JR. In Situ Maleimide Bridging of Disulfides and a New Approach to Protein PEGylation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:132–136. doi: 10.1021/bc1004685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith MEB, Schumacher FF, Ryan CP, Tedaldi LM, Papaioannou D, Waksman G, Caddick S, Baker JR. Protein Modification, Bioconjugation, and Disulfide Bridging Using Bromomaleimides. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1960–1965. doi: 10.1021/ja908610s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Katchalski E, Benjamin GS, Gross V. The Availability of the Disulfide Bonds of Human and Bovine Serum Albumin and of Bovine γ-Globulin to Reduction by Thioglycolic Acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:4096–4099. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang M, Dutta C, Tiwari A. Disulfide-Bond Scrambling Promotes Amorphous Aggregates in Lysozyme and Bovine Serum Albumin. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:3969–3981. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi K, Nakamura N, Sumi A, Ohmura T, Yokoyama K. The development of recombinant human serum albumin. Ther Apher. 1998;2:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.1998.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MALDI-MS peaks at m/z 33,372 and 22,326 could also be observed, corresponding to doubly and triply protonated species respectively.

- 42.Kim Y, Ho SO, Gassman NR, Korlann Y, Landorf EV, Collart FR, Weiss S. Efficient Site-Specific Labeling of Proteins via Cysteines. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:786–791. doi: 10.1021/bc7002499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.It is worth noting that the cytotoxicity of PTX in the absence of HSA may be influenced by the amount of residual DMSO. In this study, PTX solutions were prepared by serial dilution with PBS and/or HSA in PBS from a 585 μM stock solution in DMSO (see Figure S1, Supporting Information).

- 44.PTX at the same concentration in PBS without HSA also formed large (>200 nm) aggregates over the same period of time.

- 45.Weksler B, Romero IA, Couraud PO. The hCMEC/D3 cell line as a model of the human blood brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:16, 10. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otani M, Natsume T, Watanabe JI, Kobayashi M, Murakoshi M, Mikami T, Nakayama T. TZT-1027, an antimicrotubule agent, attacks tumor vasculature and induces tumor cell death. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:837–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higher PTX concentrations were necessary, due to the limited efficiency of PTX radiolabeling and sensitivity of the scintillation detector. PTX concentrations in the basolateral compartment are estimated to be 0.1–10 nM, depending on the time point.

- 48.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Kinetics of P-Glycoprotein-mediated efflux of paclitaxel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1236–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surapaneni MS, Das SK, Das NG. Designing Paclitaxel Drug Delivery Systems Aimed at Improved Patient Outcomes: Current Status and Challenges. ISRN Pharmacol. 2012;2012:623139, 15. doi: 10.5402/2012/623139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Later versions of this software have been tested, and found to produce very similar results.

- 51.Mehtala JG, Torregrosa-Allen S, Elzey BD, Jeon M, Kim C, Wei A. Synergistic Effects of Cisplatin Chemotherapy and Gold Nanorod-Mediated Hyperthermia on Ovarian Cancer Cells. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1939–1955. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.