Abstract

Background and study aims: The authors previously reported that the white opaque substance (WOS) in gastric epithelial neoplasia was caused by accumulation of lipid droplets by immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic studies of adipophilin, which was recently identified and validated as a marker of lipid droplets. The aim of the current study was to investigate the characteristics of the histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype in WOS-positive gastric epithelial neoplasias.

Patients and methods: A total of 130 gastric epithelial neoplasias (45 adenomas and 85 early adenocarcinomas) from 120 patients were retrospectively evaluated. The presence or absence of WOS was evaluated by M-NBI. Lipids were examined by immunohistochemical staining for adipophilin. Tissue phenotypes were immunohistochemically classified as intestinal (I), gastrointestinal (GI), and gastric (G) using antibodies against CD10, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6. The histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype of WOS-positive neoplasias were characterized and examined according to adipophilin expression.

Results: The presence of WOS by M-NBI was correlated with histologic differences between adenoma or differentiated type adenocarcinoma and mixed type or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma (P = 0.0153). Adipophilin was only expressed in primary adenoma and well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma components but not in undifferentiated components. WOS and adipophilin expression were only observed in neoplasias with I or GI phenotypes, but not in those with the G phenotype (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions: WOS in gastric epithelial neoplasias might indicate differentiation into a mature histological subtype with GI or I mucin phenotype.

Introduction

White opaque substance (WOS) on magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging (M-NBI) was first reported by Yao et al. 1 as a substance in the superficial area of gastric neoplasias that obscured the subepithelial microvascular architecture. In cases in which the presence of WOS prevent visualization of the microvascular architecture, morphologic differences in WOS are used as an optical indicator for discriminating adenomas from adenocarcinomas 1 2. Recently, Yao et al. reported that WOS is caused by lipid droplets and used oil-red-O staining to detect the accumulation of lipid droplets in the cells of WOS-positive gastric neoplasms 3. In a previous study from our group, the accumulation of lipid droplets was confirmed as a cause of WOS in gastric neoplasias by immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic studies of adipophilin, which was recently identified and validated as a marker of lipid droplets 4. The presence of WOS was recently reported in epithelial neoplasms in other gastrointestinal organs, such as colorectal neoplasias and esophageal adenocarcinoma 5 6.

Studies on Helicobacter pylori infection-associated intestinal metaplasia of the stomach used lipid staining and light microscopy or electron microscopy and showed that the epithelium in intestinal metaplasia has the ability to absorb lipid droplets 7 8. Although the mechanism underlying the accumulation of lipid droplets in WOS-positive gastric neoplasias remains unknown, the resynthesis of triglycerides from external lipids was speculated to be involved 3. In a recent study, Ohtsu et al. demonstrated that WOS is related to external lipids, and that oral ingestion of foods containing emulsified lipids increases the density of the WOS in epithelial neoplasias including adenoma and adenocarcinoma 9. These novel findings suggest that new techniques can be developed to improve our ability to accurately diagnose gastric neoplasias. However, the types of gastric epithelial neoplasias that can absorb lipids and the histologic types that do not have the absorption function remain unclear. Therefore, the possible limitations of fat loading tests need to be defined. Accordingly, the development of a novel functional endoscopy technique that utilizes the lipid absorption capacity of gastric neoplasias requires clarification of the histologic differentiation and mucin phenotypes of WOS-positive neoplasias including adenomas and adenocarcinomas.

Considering that WOS in gastric neoplasia is associated with the absorption of lipid droplets, WOS-positive gastric neoplasms may represent a mature histologic form and a mucin phenotype similar to that of intestinal metaplasia. The mucin phenotype of WOS-postive gastric neoplasias has been identified as either intestinal or gastrointestinal 3; however, this study was limited by a small sample size. Furthermore, differentiated adenocarcinomas can vary histologically according to tumor size and can contain dedifferentiated components with different mucin phenotypes. Therefore, histologic investigation based on the immunohistochemical detection of adipophilin in a large number of gastric epithelial neoplasias of various histologic types is more desirable for the precise analysis of lipids. In addition, there are currently no reports describing the histologic differentiation of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias. The purpose of the current study was to investigate the histologic differentiation of WOS-positive gastric epithelial neoplasias and their association with a mucin phenotype.

Patients and methods

Patients

The current study was a retrospective evaluation of the endoscopic image database of Oita Red Cross Hospital Endoscopy Unit. The institutional review board of Oita Red Cross Hospital approved the study. Between July 2009 and June 2013, 161 gastric epithelial neoplasias (adenoma or early gastirc cancer) from 151 consecutive patients referred to our departments for tumor resection by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) were subjected to endoscopic examination using M-NBI.

Gastric epithelial neoplasias from consecutive patients who fulfilled the following criteria were included in this study: (1) patients who provided written informed consent; and (2) patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical resection at Oita Red Cross Hospital and who had a confirmed histologic diagnosis of adenoma or early gastric cancer. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) neoplasias in which a detailed comparison of histologic and endoscopic findings was difficult; (2) neoplasias measuring < 5 mm; and (3) neoplasias from remnant stomach. The reason for exclusion criterion (2) was that evaluation of immunohistochemical findings is difficult in small lesions. The reason for exclusion criteria (3) was that rich bile acids in the remnant stomach can affect M-NBI observations 10.

Finally, 130 gastric epithelial neoplasias (adenoma or early gastric cancer) from 120 patients who fulfilled the above mentioned criteria were included in the study. Of 130 neoplasias, 123 (94.6 %) were resected by ESD, and 7 (5.4 %) were resected by surgery.

Endoscopic procedure

The instruments used in the current study were a high-resolution magnifying upper gastrointestinal endoscope (GIF-Q240Z;Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) or a high-definition magnifying upper gastrointestinal endoscope (GIF-H260Z; Olympus Medical systems, Tokyo, Japan) and an electronic endoscopy system (EVIS LUCERA Spectrum; Olympus Medical Systems). A soft black hood (MAJ-1988 for the GIF-Q240Z, MAJ-1989 for the GIF-H260Z; Olympus) was mounted at the tip of the endoscope to enable the endoscopist to fix a consistent focal distance between the tip of the endoscope and the gastric mucosa. M-NBI examinations and the recording of endoscopic findings were carried out by four endoscopists ( T. U., K. T, Y. Y, and M. F.). The presence or absence of WOS was determined in each of the neoplasias based on the findings of M-NBI. Neoplasias with a partially positive WOS were considered “WOS positive”. For assesment of the background gastric mucosa, atrophy was graded endoscopically according to the Kimura and Takemoto classification 11.

Immunohistochemical staining and assesment of adipophilin expression and the mucin phenotype

Sections (4 mm thick) were cut from representative paraffin-embedded blocks of resected tumors and mounted on silane-coated glass slides. One section from each block was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). All sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation with 3 % hydrogen peroxide for 20 minutes at room temperature. The slides were autoclaved in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 121 °C for 15 min. Lipid accumulation was detected using a primary antibody against adipophilin (clone AP125, lot 007281, Acris Antibodies GmbH, Hiddenhausen, Germany), which can be used for the detection of lipid droplets in paraffin-embedded sections 12 13. For the identification of tissue phenotypes, primary antibodies against MUC2 (clone NCL-MUC2, lot 6008336, Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom), MUC5AC (lot 6003413, Novocastra), MUC6 (lot 6003414, Novocastra), and CD10 (lot 6005650, Novocastra) were used. After immersion in normal goat serum (1 : 10) for 10 minutes, sections were incubated with primary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature, washed, and incubated for 30 minutes with secondary antibodies conjugated to a horseradish peroxidase-labeled polymer (Envision™, Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA). Immunoreacting products were visualized with 0.02 % 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.005 % hydrogen peroxide, and nuclei were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Sections incubated with normal mouse IgG or pre-immune rabbit serum instead of the corresponding primary antibodies and anti-sera were used as negative controls. Positive immunostaining for adipophilin was defined as > 5 % of positively stained neoplastic cells in the surperficial neoplastic areas. The results of immunostaining for MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2 and CD10 were defined as described previously 14. Briefly, the tissue phenotypes were immunohistochemically classified into gastric (G), intestinal (I), and gastrointestinal (GI) types (gastric markers were MUC5AC and MUC6, and intestinal markers were MUC2 and CD10). Positive expression was defined as > 5 % of positively stained neoplastic cells. The histologic evaluation was performed by an expert pathologist ( H. Y.) who was blinded to the endoscopic findings.

Histopathologic assessment

Histopathologic assessment was performed according to the Japanese classification of Gastric Carcinoma (14th edition) 15. Differentiated-type adenocarcinomas were defined as those with a glandular structure, including well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1); moderately-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub2); and papillary adenocarcinoma (pap). Undifferented-type adenocarcinomas were defined as those with indistinct or no glandular structure, including solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por1); non-solid-type, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por2); and signet-ring cell carcinoma (sig); and mucinous adenocarcinoma (muc). Excluding adenomas, adenocarcinomas were classified into the following three histologic types according to the proportions of differentiated and undifferentiated components: differentiated type (composed of differentiated type only), mixed type (mixed predominantly differentiated or mixed predominantly undifferentiated), and undifferentiated type (undifferentiated type only). In this study, we speculated that WOS-positive gastric neoplasms may represent a mature histologic form similar to that of intestinal metaplasia. To evaluate the histologic characteristics of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias, we reclassified adenomas and the three histologic types of adenocarcinomas into two categories: adenoma or differentiated type adenocarcinoma and mixed type or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma.

The following parameters were evaluated: (1) characteristics of histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype in WOS-positive gastric epithelial neoplasms; and (2) characteristics of histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype according to adipophilin expression.

Statististical analysis

All continuous variables are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD). For parametric variables, the Student’s t-test was used to compare the means between two groups; otherwise, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of the prevalence between the groups. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias (Table 1)

Table 1. Clinicopathologic characteristics of WOS-positive gastric neoplasia.

| WOS-positive neoplasia(51) | WOS-negative neoplasia(79) | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 71.8 ± 9.2 | 70.9 ± 8.9 | 0.4739 |

| Male/female | 44/7 | 57/22 | 0.0590 |

| Tumor size, mean ± SD (mm) | 19.7 ± 16.0 | 17.0 ± 11.3 | 0.2660 |

| Macroscopic type 0-I, 0-IIa/0-IIb, 0-IIc | 37/14 | 35/44 | 0.0021 |

| Tumor location (L/MU) | 18/33 | 36/43 | 0.2775 |

| Tumor color (whitish/reddish) | 33/18 | 16/63 | < 0.0001 |

| Histologic type (adenoma/adenocarcinoma) | 29/22 | 16/63 | < 0.0001 |

| Depth of invasion (M/SM) | 44/7 | 63/16 | 0.4807 |

| H .pylori-related advanced atrophic gastritis | 51/0 | 76/3 | 0.2792 |

| Resection method (ESD/surgical) | 48/3 | 75/4 | 0.8399 |

WOS, white opaque substance; SD, standard deviation; 0-I, protruding; 0-IIa, superficial elevated; 0-IIb, flat; 0-IIc, superficial shallow depressed; L, lower stomach; M, middle stomach; U, upper stomach; M, mucosa; SM, submucosa; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection.

A total of 130 gastric epithelial neoplasias (adenoma or early gastric cancer) from 120 patients were included in this study. The average age of the patients was 71 years (range, 45 – 91 years). The male:female ratio was 91 : 29. Of the130 neoplasias, 51 were WOS-positive by M-NBI. Statistically significant differences in macroscopic type, tumor color (whitish vs. reddish), and histologic type (adenoma vs. adenocarcinoma) were observed between WOS-positive and WOS-negative neoplasias. The background gastric mucosa of all WOS-positive neoplasias was categorized as H. pylori-related advanced atrophic gastritis, as defined by endoscopic evidence of advanced mucosal atrophy diagnosed as open-type atrophic gastritis by the Kimura and Takemoto classification 11. WOS was frequently observed in protruding or superficial-elevated macroscopic type, and associated with whitish tumor color and adenoma predominance (Table 1).

Immunohistochemical detection of adipophilin according to the presence of WOS by M-NBI

The presence of WOS by M-NBI was positively correlated with adipophilin expression. Of the 51 WOS-positive neoplasias, 50 (98.0 %) were positive for adipophilin, whereas 13 of the 79 WOS-negative neoplasias (16.5 %) were positive for adipophilin (Table 2). A statistically significant correlation between the presence of WOS and the expression of adipophilin by immunohistochemistry was observed (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 2. Immunohistochemical detection of adipophilin according to the presence of WOS by M-NBI.

| Adipophilin-positive | Adipophilin-negative | |

| WOS-positive neoplasias (n = 51) | 50 (98.0 %) | 1 (2.0 %) |

| WOS-negative neoplasias (n = 79) | 13 (16.5 %) | 66 (83.5 %) |

WOS, white opaque substance; M-NBI, magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging.

Histologic characteristics of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias

The 130 gastric epithelial neoplasias analyzed comprised 45 adenomas and 85 early adenocarcinomas. Early adenocarcinomas were classified into three types according to the proportions of differentiated and undifferentiated components as follows: 68 differentiated type (55 well differentiated and 13 moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinomas, and 0 papillary adenocarcinoma); nine mixed type (9 mixed predominatly differentiated type and 0 mixed predominatly undifferentiated type); and eight undifferentiated type (5 poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, 3 signet ring cell carcinomas, and 0 mucinous adenocarcinoma) (Table 3).

Table 3. Histologic and phenotypic features according to the detection of adipophilin.

| Histologic subtype | Adipophilin-positive (63) | Adipophilin-negative (67) |

| Adenoma | 32 | 13 |

| Differentiated type adenocarcinoma | 28 | 40 |

| Mixed predominantly differentiated adenocarcinoma | 3 | 6 |

| Mixed predominantly undifferentiated adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 |

| Undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma | 0 | 8 |

| Mucin phenotype | 63 | 67 |

| Intestinal type | (38) | (12) |

| Gastrointestinal type | (25) | (31) |

| Gastric type | (0) | (24) |

The presence of WOS by M-NBI was associated with the histologic difference between adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type and mixed type or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma. In WOS-positive neoplasias, 49 of 51 (96.1 %) were adenoma or differentiated type adenocarcinoma, whereas two of 51 (3.9 %) were mixed or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma ( Fig.1 and Fig. 3). In WOS-negative neoplasias, 64 of 79 (81.0 %) were adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type, whereas 15 of 79 (19.0 %) were adenocarcinoma of mixed or undifferentiated type (P = 0.0153, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 4). The presence of the WOS has a sensitivity of 43.4 % and a specificity of 88.2 % for the diagnosis of the the lesion classified as adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type but not mixed or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma.

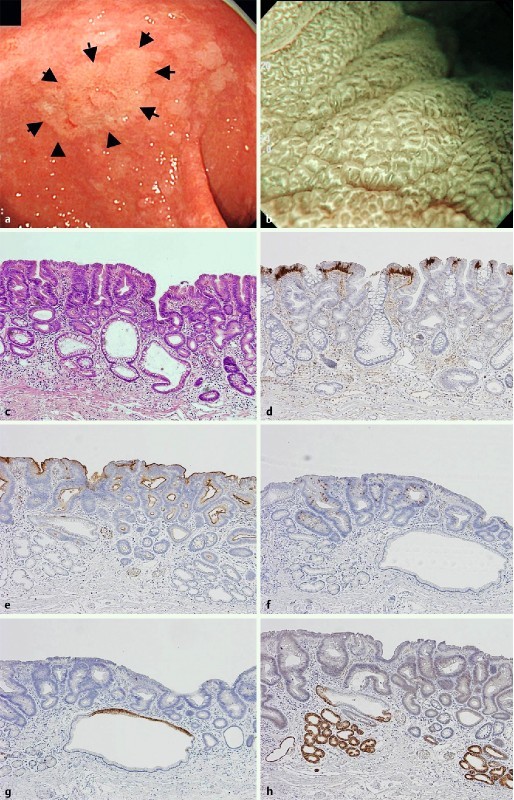

Fig. 1.

Low-grade adenoma with intestinal phenotype as one of the representative WOS-positive gastric neoplasias. a slightly whitish colored 0-IIa type neoplasm (arrow) was observed at the gastric antrum with white light endoscopy. b Magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging (M-NBI) shows the regular WOS. Morphology of WOS showing a well-organized and symmetrical distribution with a regular reticular pattern. The subepithelial microvascular pattern could not be visualized because a dense WOS obscured the subepithelial microvessels. c Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected specimen shows a tubular adenoma of low-grade. d Adipophilin was mainly detected within the superficial neoplastic epithelium of intervening apical regions between the crypts. e CD10 was detected in the luminal side of the neoplastic glands. f MUC2 was diffusely detected in the neoplastic glands. g Neoplastic glands were negative for MUC5AC. Non-neoplastic epithelium at the superior portion shows positive focal expression. h Neoplastic glands were negative for MUC6. Non-neoplastic epithelium at the deep portion shows positive focal expression.

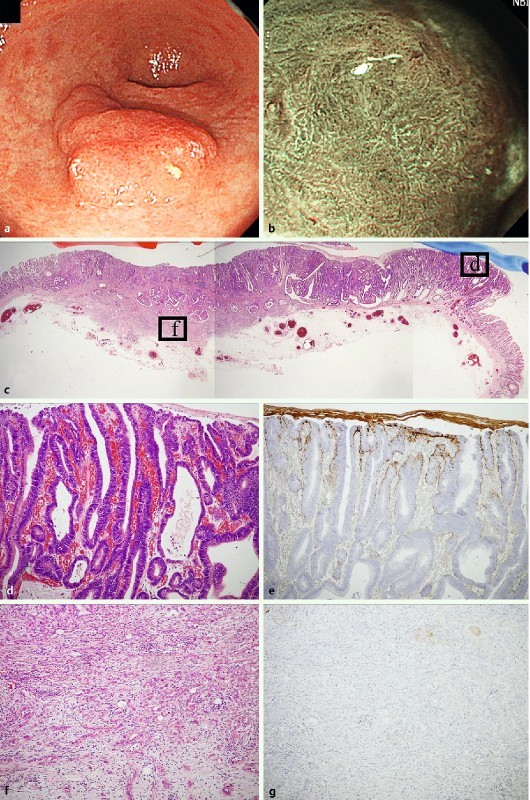

Fig. 3.

Mixed type (mixed predominatly differentiated type) early adenocarcinoma of gastrointestinal phenotype as a representative WOS-positive gastric neoplasia. a. A slightly elevated reddish colored 0-IIa type neoplasia was observed at the gastric antrum with white light endoscopy. b M-NBI findings showed the irregular WOS at the oral side of the tumor. c Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected specimen. The tumor was composed of an intramucosal well to moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma component and an invasive poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma component visualized at low magnification. d High maginification of box d in Fig. 3 c showed that the tumor glands were composed of well differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. In this area, WOS was detected by M-NBI. e Positive adipophilin expression was only observed in the well differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma component. f High maginification of box f in Fig. 3 c shows poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cells invading the submucosal layer. g Adipohilin expression was not detected in the poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma component.

Table 4. Histologic difference according to the presence of WOS by M-NBI.

| Adenoma or differentiated-type adenocarcinoma | Mixed-type or undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma | |

| WOS-positive neoplasias (n = 51) | 49 (96.1 %) | 2 (3.9 %) |

| WOS-negative neoplasias (n = 79) | 64 (81.0 %) | 15 (19.0 %) |

WOS, white opaque substance; M-NBI, magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging.

Examination of the relationship between histologic subtype and adipophilin expression yielded similar results. Adipophilin expression was only observed in adenoma and well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma components (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). By contrast, adipophilin expression was not detected in undifferentiated components (Table 3, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

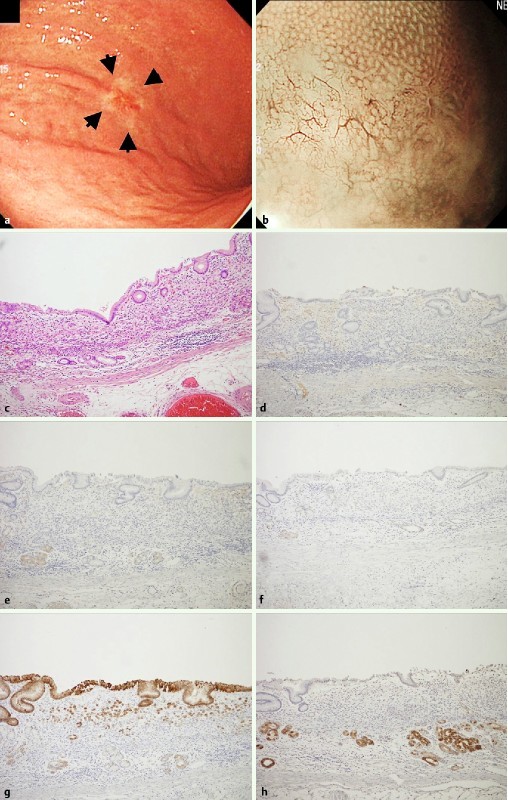

Fig. 2.

Undifferentiated early adenocarcinoma with gastric phenotype as one of the representative WOS-negative gastric neoplasias. a A slightly reddish and whitish colored 0-IIc type neoplasia (arrow) was observed at the lower body of the stomach with white light endoscopy. b WOS was not detected by M-NBI. c Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected specimen shows signet ring cell carcinoma cells infiltrating the intramucosal layer. d No adipophilin postive cells were observed. e Neoplastic cells and the adjacent non-neoplastic epithelium were negative for CD10. f Neoplastic cells and the adjacent non-neoplastic epithelium were negative for MUC2. g Neoplastic cells located on the surface and the residual non-neoplastic epithelium were positive for MUC5AC. h Neoplastic cells were negative for MUC6, but the non-neoplastic epithelium at the deep portion was positive for MUC6 focally.

Phenotypic findings of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias

The 130 gastric epithelial neoplasias were classified into three tissue phenotypes based on immunohistochemical findings as follows: I type, 50; GI type, 56; and G type, 24. Of the 51 WOS-positive neoplasias, 33 (64.7 %) were I, 18 (35.3 %) were GI, and 0 (0 %) were G phenotypes. Therefore, WOS was only observed in either I or GI phenotypes, but not in the G phenotype (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 5). Similar results were obtained in the assessment of the relationship between tissue phenotypes and adipophilin expression. Adipophilin expression was positive in the I (38/63, 60.3 %) and GI (25/63, 39.7 %) phenotypes (Table 3, Fig. 1), whereas it was negative in the G (0/63, 0 %) phenotype (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test) ( Table3, Fig. 2).

Table 5. Phenotypic findings of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias.

| I type or GI type | G type | |

| WOS-positive neoplasias (n = 51) | 51 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| WOS-negative neoplasias (n = 79) | 55 (69.6 %) | 24 (30.4 %) |

WOS, white opaque substance; I, intestinal; GI, gastrointestinal; G, gastric.

Discussion

In the current study, two main clinicopathological definitions were made, namely the characteristics associated with the histologic differentiation of WOS-positive gastric neoplasias and the characteristics of the mucin phenotype in WOS-positive gastric neoplasias.

The results of the current study indicated that the presence of WOS by M-NBI was correlated with the histologic difference between adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type and mixed type or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma. WOS-positive neoplasias were histologically composed of adenoma or differentiated type adenocarcinoma (96.1 %), and mixed or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma (3.9 %). WOS-negative neoplasias were histologically composed of adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type (81.0 %), and mixed or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma (19.0 %) (P = 0.0153, Fisher’s exact test). In other words, the presence of the WOS has a sensitivity of 43.4 %, specificity of 88.2 %, positive predictive value of 96.1 %, and negative predictive value of 19.0 % for the diagnosis of the lesion classified as adenoma or adenocarcinoma of differentiated type but not mixed or undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma.

Our immunohistochemical studies identified a relationship between detailed histological subtype and the expression of adipophilin. Adipophilin expression, which represents the accumulation of lipid droplets, was only observed in adenoma and well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma components but not in undifferentiated component. These findings could potentially be of value in routine medical practice. Recent advances in M-NBI allow endoscopic observation down to the capillary level and some previous reports describe the usefulness of endoscopic findings for differentiating tumor histology. Differentiated type early adenocarcinoma often exhibits two patterns on M-NBI. The first is an uneven network of irregular microvessels with the absence of a microsurface structure 16. The second is irregular microvessels situated in the irregular papillary microsurface structure 17. Undifferentiated type early adenocarcinoma often shows corkscrew-like irregular microvessels with the absence of a microsurface structure 16. Compared with the above mentioned M-NBI findings, WOS might be superior in that it represents not only a qualitative diagnosis from the aspect of morphologic differences, but also indicates histologic features including differentiation and the mucin phenotype of the tumor itself. Therefore, it is suggested that WOS-positive lesions could be classified as adenoma or differentiated adenocarcinoma (principally well to moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma) with GI or I mucion phenotype but not undifferentiated adenocarcinoma regardless of the mucin phenotype. These novel findings could be useful for investigating the pathogenesis of gastric neoplasias and histological differentiation.

In the current study, although WOS was associated with the expression of adipophilin, there were 14 exceptions. In 13 of 14 cases, adipophilin expression was positive despite a negative endoscopic result. All of these cases were adenomas or well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with I or GI phenotype. A review of the histologic findings showed that adipophilin was faintly expressed in a small area. Hence, we speculated that the small amout of lipids could not be identified as WOS endoscopically despite being microscopically evident. These findings suggest that an adequate amount of lipid accumulation is necessary for the endoscopic identification of WOS, as WOS is visualized by strong reflection or backward scattering of the projected light 3. Furthermore, we found that in certain adenomas with intestinal phenotypes, the degree of WOS increased and was evident after oral administration of a proton pump inhibitor (data not shown), which suggests that WOS is not constant and persistent. WOS may be closely associated with factors such as diet or the pH of fasting gastric juce, which can affect the absorption of lipids by neoplasias. A study by Ohtsu et al. showed that WOS positivity and density increase when micellar lipid is loaded before endoscopic examination 9. Futher intensive laboratory work is needed to clarify the association between WOS and the pH of fasting gastric juce.

In the current study, we defined the phenotypic characteristics of WOS-positive and WOS-negative gastric neoplasias. We used two approaches to clarify this issue. One was similar to that used by Yao et al. 3, in which the phenotypic chracteristics associated with WOS were evaluated by M-NBI. In the second method, we evaluated phenotype according to adipophilin expression. A total of 51 WOS-positive neoplasias were classified into 33 (64.7 %) type I, 18 (35.3 %) type GI, and 0 (0 %) type G, indicating that WOS was only present in I or GI phenotypes, but not in the G phenotype (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). Our current results were in agreement with those previously reported by Yao et al. 3. In addition, similar results were obtained in our immunohistochemical examination of the relationship between tissue phenotypes and the expression of adipophilin. Adipophilin expression was only observed in the I or GI phenotype, but not in the G phenotype. Taken together with the results of Yao et al. 3, our findings indicate that lipid accumulation is present in the I or GI phenotypes, but not in the G phenotype. The identification of the phenotype of gastric neoplasias before treatment is important. Differentiated type adenocarcinomas of gastric phenotype are considered highly malignant, possessing high invasiveness and high metastatic potential, compared with those of intestinal phenotype 18. Among adenomas, those of gastric phenotype are named “pyloric gland adenoma” and have a higher malignant potential than intestinal type adenomas 19. Ueyama et al. reported that a WOS-positive epithelium indicated dysplastic changes in gastric hyperplastic polyps 20. Although gastric hyperplastic polyps usually have a gastric phenotype, change from a gastric to an intestinal phenotype is associated with malignant transformation 21. Considering the possibility that the appearance of WOS in gastric hyperplastic polyps may represent their malignant transformation, the case report by Ueyama et al. 20 is interesting and useful for the management of gastric hyperplastic polyps.

The current study had several limitations associated with its retrospective nature. In addition, the study was a single-center study. There could be a population bias in the tumor histology because patients were referred to our department for the purpose of endoscopic resection. This could explain the small number of undifferentiated type adenocarcinomas. We reviewed the medical records of all patients with early gastric cancer, in particular those with undifferentiated type adenocarcinoma who were referred to the Department of Surgery at Oita Red Cross Hospital during the study period using a registry of operation records, although they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria of this study and were not included in the main data. We identified 10 patients with undifferentiated type early gastric cancer. Of these 10 cases, eight received magnifying endoscopic examination and their endoscopic findings were available to examine the presence of WOS. Furthermore, the expression of adipophilin and mucin phenotypes were evaluated in these eight cases. The results were consistent with those of the current study and showed that WOS and adipophilin expression were not observed in undifferentiated type adenocarcinomas regardless of the mucin phenotype. However, further well-designed studies with a large number of cases with undifferentiated type early gastric cancer are necessary to verify the present results.

In conclusion, the crurent study suggested to us that WOS in gastric epithelial neoplasias might be an indicator of histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype. WOS in gastric epithelial neoplasias might indicate differentiation into a mature histologic subtype with a GI or I mucin phenotype.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. M. Miyazaki for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Yao K, Iwashita A, Tanabe H. et al. White opaque substance within superficial elevated gastric neoplasm as visualized by magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging: a new optical sign for differentiating between adenoma and carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:574–580. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao K, Iwashita A, Tanabe H. et al. Author’s reply to Letter to the Editor, “White opaque substance” and “light blue crest” within gastric flat tumors or intestinal metaplasia: same or different signs? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:402–403. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao K, Iwashita A, Nambu M. et al. The nature of white opaque substance in the gastric adenoma and cancer as visualized by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Yada N. et al. White opaque substance represents an intracytoplasmic accumulation of lipid droplets: Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic investigation of 26 cases. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshi S, Kato M, Honma K. et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma with white opaque substance obserbed by magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2014:12331. doi: 10.1111/den. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hisabe T, Yao K, Imamura K. et al. White opaque substance visualized using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in colorectal epithelial neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2544–2549. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin W, Ross L L, Jeffries G H. et al. Some physiologic properties of heterotopic intestinal epithelium: Its role in transporting lipid into the gastric mucosa. Lab Invest. 1967;16:813–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirula M, Tarpila S. Absorptive function of intestinal metaplasia of the stomach. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1968;3:76–79. doi: 10.3109/00365526809180102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohtsu K Yao K Matsunaga K et al. Lipid is absorbed in the stomach by epithelial neoplasms (adenomas and early gastric cancers): a novel functional endoscopy Endoscopy International Open(in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johannesson K A, Hammar E, Staël von Holstein C. et al. Mucosal changes in the gastric remnant: long-term effects of bile reflux diversion and Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:35–40. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophy border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heid H W, Moll R, Schwetlick I. et al. Adipophilin is a specific marker of lipid accumulation in diverse cell types and diseases. Cell tissue Res. 1998;294:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s004410051181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moritani S, Ichihara S, Hasegawa M. et al. Intracytoplasmic lipid accumulation in apocrine carcinoma of the breast evaluated with adipophilin immunoreactivity: a possible link between apocrine carcinoma and lipid-rich carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:861–867. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821a7f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi M, Takeuchi M, Ajioka Y. et al. Mucin phenotype and narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy for differentiated-type mucosal gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1064–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association . Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayoshi T, Tajiri H, Matsuda K. et al. Magnifying endoscopy combined with narrow band imaging system for early gastric cancer: Correlation of vascular pattern with histopathology (including video) Endoscopy. 2004;36:1080–1084. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yokohama A, Inoue H, Minami H. et al. Novel narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopic classification for early gastric cancer. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010;42:704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koseki K, Takizawa T, Koike M. et al. Distinction of differentiated type early gastric carcinoma with gastric type mucin expression. Cancer. 2000;89:724–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vieth M, Kushima R, Borchard F. et al. Pyloric gland adenoma: a clinico-pathological analysis of 90 cases. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:317–321. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, Nagahara A. et al. A White opaque substance-positive gastric hyperplastic polyp with dysplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4262–4266. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao T, Kajiwara M, Kuroiwa S. et al. Malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps: alteration of phenotypes, proliferative activity, and p53 expression. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:1016–1022. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.126874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]