Abstract

Background and study aims: Injuries to the esophageal wall, such as perforations and anastomotic leaks, are serious complications of surgical and endoscopic interventions. Since 2006, a new treatment has been introduced, in the form of endoscopically placed vacuum sponge therapy.

Patients and methods: Between April 2012 and October 2014, 10 patients (5 men and 5 women) aged 57 to 94 years were treated at our institution using endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Results: The defect in the esophageal wall was successfully closed in seven of the 10 patients (70 %). No severe complications occurred.

Conclusions: EVT is a valuable tool for management of defects in the esophageal wall and should be considered as a treatment option for patients with this condition.

Introduction

Injuries to the esophageal wall, such as perforations and anastomotic leaks, are serious complications of surgical and endoscopic interventions and are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Mortality occurs in up to 20 % of conservatively managed and 64 % of surgically managed anastomotic leakages in affected patients 1 2. Avoiding the invasiveness of repeated surgery, implantation of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) or plastic stents is a well-known option for closing defects and is successful in 77 % to 84 % of cases 3. However, stent migration, prolonged treatment lasting several weeks with impaired food intake, and difficulty in removing the stent are common side effects of this form of treatment 4. Additional techniques for closing esophageal defects include standard clips 5 and clipping devices such as the over-the-scope clip (OTSC) 6 7, and there have been a few reported cases describing the use of suturing devices 8.

In patients with mediastinal abscesses, all of the techniques mentioned above should be accompanied by transcutaneous mediastinal drainage, with computed tomography (CT) guidance, in order to avoid enlargement of the abscess and sepsis.

Since 2006, a new treatment have been available, in the form of endoscopically placed vacuum sponge therapy. The technique was initially used in the lower gastrointestinal tract in patients with pararectal abscesses due to anastomotic insufficiencies after rectal surgery. It involves placing an open-core sponge in the abscess cavity, connected to a drainage tube with a negative-pressure pump 9 10. In recent years, this approach has also been adapted for use in the upper gastrointestinal tract and it is used as an alternative in the treatment of patients with upper gastrointestinal perforations or leakages.

Only very few institutions have published reports on their experience with this new technique to date.

Patients and methods

Between April 2012 and October 2014, 10 patients (5 men and 5 women) aged 57 – 94 years were treated at our institution using endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) in the upper gastrointestinal tract (Table 1).

Table 1. Data on patients.

| Sex | Age | Location of perforation or esophageal insufficiency | Cause | Location of sponge | Duration of treatment | No. of sponge exchanges | Sedation vs. anesthesia | Time from detection to start of treatment | Success | |

| 1 | Male | 64 | Esophagus 32 cm | Anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus | Extraluminal | 5 months | 39 | Anesthesia | > 24 h (12 weeks) | No |

| 2 | Female | 83 | Esophagus 16 cm | Iatrogenic endoscopic perforation | Intraluminal | 5 days | 0 | Anesthesia | < 24 h | Yes |

| 3 | Male | 87 | Esophagus 17 cm | Anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus | Extraluminal | 4 days | 1 | Anesthesia | > 24 h | No |

| 4 | Male | 72 | Piriform recess/proximal esophagus | Iatrogenic perforation after removal of a foreign body (dental prothesis) | Intraluminal | 5 days | 0 | Anesthesia | 20 h | Yes |

| 5 | Male | 65 | Esophagus 28 cm | Anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus | Intraluminal | 12 days | 2 | Sedation | > 24 h | Yes |

| 6 | Female | 57 | Esophagus 22 cm | Perforation by a foreign body (peach pit) | Extraluminal | 26 days | 6 | Anesthesia | > 24 h | Yes |

| 7 | Female | 77 | Piriform recess/ proximal esophagus | Iatrogenic perforation during intubation | Intraluminal | 5 days | 0 | Anesthesia | > 24 h | Yes |

| 8 | Female | 76 | Esophagus 33 cm | Anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus | Extraluminal | 4 days | 0 | Sedation | < 24 h | Yes |

| 9 | Male | 64 | Esophagus 28 cm | Anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus | Extraluminal | 1 day | 0 | Sedation | < 24 h | No; surgical closure of the leak |

| 10 | Female | 94 | Esophagus 20 cm | Iatrogenic endoscopic perforation | Extraluminal | 24 days | 4 | Anesthesia | > 24 h (16 days) | Yes |

Patients

The leak was located in the esophagus in eight patients and in the very proximal esophagus and piriform recessus in two patients. All of the patients had severe signs of perforation, such as mediastinitis and/or cutaneous emphysema. In six patients, the abscess cavity was large enough for the sponge to be placed into the cavity, while in the other four patients, the sponge was placed intraluminally. In one patient (no. 10), access to a large mediastinal cavity had to be achieved using balloon dilation of the small opening before sponge placement.

Technique of sponge placement

The commercially available EndoSponge® system (B. Braun Melsungen Ltd., Melsungen, Germany) was used in all patients. The system consists of an overtube, which is placed into the cavity or in the esophageal lumen after intubation with the endoscope. After the endoscope has been removed, the small sponge is positioned in the cavity using a pusher device over the overtube. Correct placement is checked endoscopically after removal of the overtube, and suction is applied with a negative-pressure pump (InfoV.A. C.®, Kinetic Concepts Inc., San Antonio, Texas, USA) after the tube has been redirected through the nose. The settings used for the pump were a negative pressure of 100 to 125 mmHg, high intensity, and continuous suction. Sponge changes were performed every 3 to 5 days.

Placement of the sponge and sponge changes were performed under general anesthesia in seven patients due to the proximity of the perforation, with a risk of airway impairment. In two patients with perforations of the piriform recess, continuous sedation was necessary throughout the whole treatment period to prevent pain in the deep hypopharynx and impairment of the airway.

Enteral nutrition was ensured with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) catheter in three patients and with transnasal enteral feeding tubes in seven patients. All of the conscious patients were able to drink, and patients with extraluminal sponge placement were able to eat soft food.

Results

The defect in the esophageal wall was successfully closed in seven of the 10 patients (70 %). One patient died due to fulminant sepsis during the treatment. The time between perforation or detection of an anastomotic insufficiency and the start of vacuum therapy was less than 24 hours in four patients. The time between detection and intervention was more than 14 days in two patients. The median treatment time was 5 days in patients with endoluminal sponge placement and 14 days in patients with extraluminal sponge placement. The median hospitalization time was 38 days.

The median follow-up period was 4 months. Two patients died of vascular disease (one heart attack with cardiogenic shock, one stroke with respiratory insufficiency) not related to the sponge treatment, 3 and 6 weeks, respectively, after successful closure of the esophageal defects.

Patients with failed closure

In the first patient with failed closure of a large anastomotic insufficiency after thoracoabdominal resection of the esophagus, vacuum therapy was started after two failed courses of treatment with fully covered metal stents. The wall of the abscess cavity was therefore consolidated, and it was not possible to stimulate granulation tissue through the sponge treatment. The patient also developed increasing numbers of fistulas between the abscess cavity and the peripheral bronchial airways. After a large number of sponge exchanges (n = 39), the patient died due to complications after a surgical rescue intervention.

The second patient died of fulminant sepsis, which had commenced already before the first sponge placement.

The third patient with failed sponge treatment underwent surgery early after the sponge placement, because of the development of a large pleural empyema causing sepsis. The esophagus was removed, and a cervical esophagostomy was created. The patient is awaiting a colon interposition.

Side effects and complications

All of the interventions were performed without severe side effects besides the three failed treatments mentioned above. The sponge ruptured during removal procedures in two patients. The residual parts of the sponges were easily extracted using a rat-tooth forceps, with no damage to the surrounding structures.

In one patient, an esophageal stenosis in the area of the prior sponge therapy had to be dilated using bougies. One patient with a very proximal perforation (no. 4) developed respirator-associated pneumonia during the course of treatment, due to artificial ventilation required for 5 days.

Discussion

The main causes of defects developing in the esophageal wall are anastomotic insufficiencies and iatrogenic perforations after endoscopic interventions such as endoscopic submucosal dissection or dilation. Other conditions, such as a perforation by a foreign body or spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome), only account for a small number of cases. Minimally invasive treatment options include clipping with standard or over-the-scope clips, and placement of metal or plastic stents. However, clips are limited to perforations up to 25 mm long 5, and stent placement is associated with the risks of stent migration, pain and discomfort, hemorrhage, tissue ingrowth, and food obstruction 11 12.

Surgical repair with suturing of defects, with or without interpostion of muscle flaps or esophagectomy, was the treatment of choice for many years in patients with defects of the esophageal wall. It is accompanied by a mortality rate of 10 % to 12 % 13 14. Due to the bacterial contamination of the mediastinum and the development of septic conditions, the mortality rate in patients in whom the start of treatment is delayed by > 24 hours reaches 20 %, in comparison with 7 % in patients in whom treatment starts earlier 14. In our group of patients we discovered a mortality of 20 % during treatment (patients No. 1 and 3). In both patients the treatment started after more than 24 hours, in patient No. 1, after 5 months. No death occurred in the group of patients who started treatment within 24 hours.

Cleansing of the contaminated mediastinum is one of the key points in treating esophageal perforations, and mediastinal abscesses and stent therapy should therefore be combined with mediastinal drainage in all cases in which there are detectable mediastinal abscesses. In the present group of patients, the start of therapy was > 24 hours in six patients, and two of the three patients with treatment failure belonged to this group.

A major advantage of vacuum therapy is the ability to cleanse the perforation cavity using a minimally invasive approach; this is required in order to avoid sepsis and death. In the present study, it was possible to cleanse even consolidated wound cavities, with walls covered with fibrinous tissue, to produce fresh granulation tissue during the first 3 to 5 days of vacuum-assisted treatment (Fig. 1 – 5). This effect has been well known since the first endoscopic lesions were treated with vacuum therapy in the rectum 15. The effectiveness of sponge cleansing has also led to its use in infected pancreatic pseudocysts in two cases, with good resolution of the cavities 16 17.

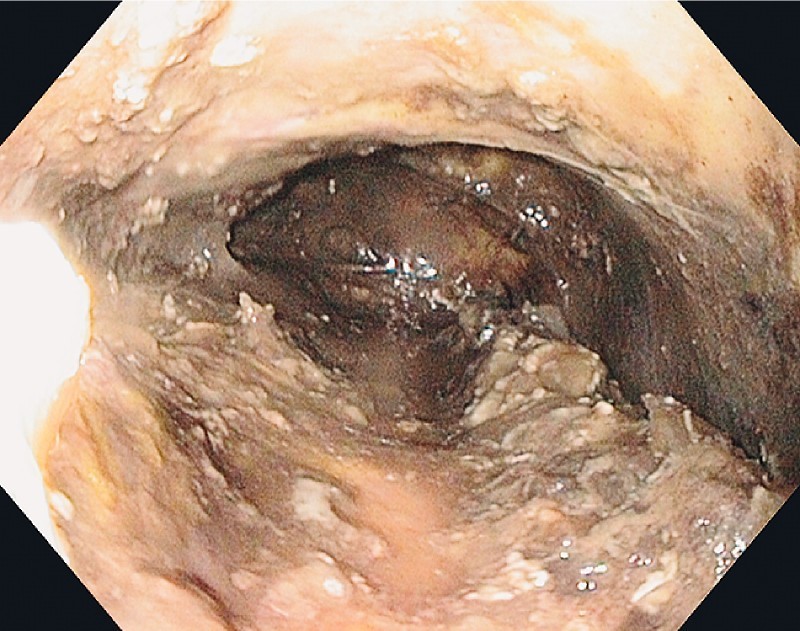

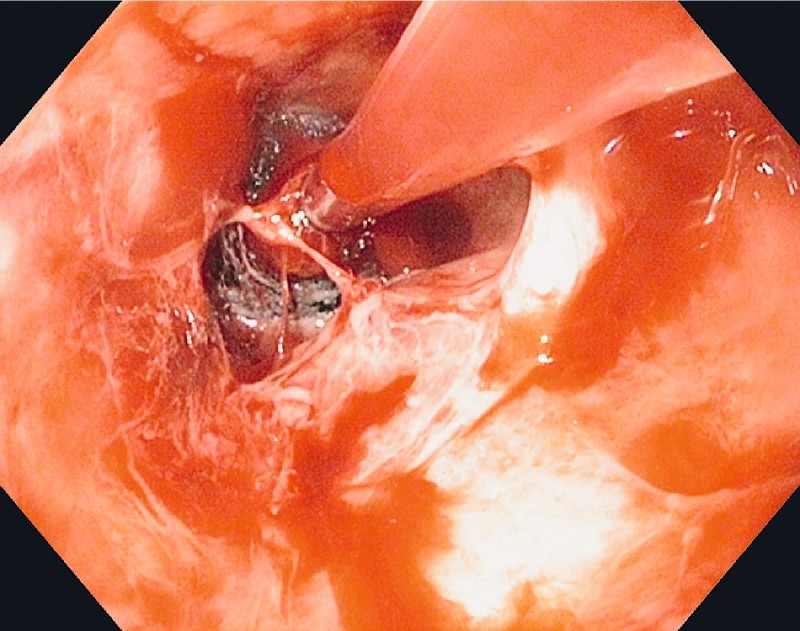

Fig. 1.

Initial endoscopic view into the mediastinum.

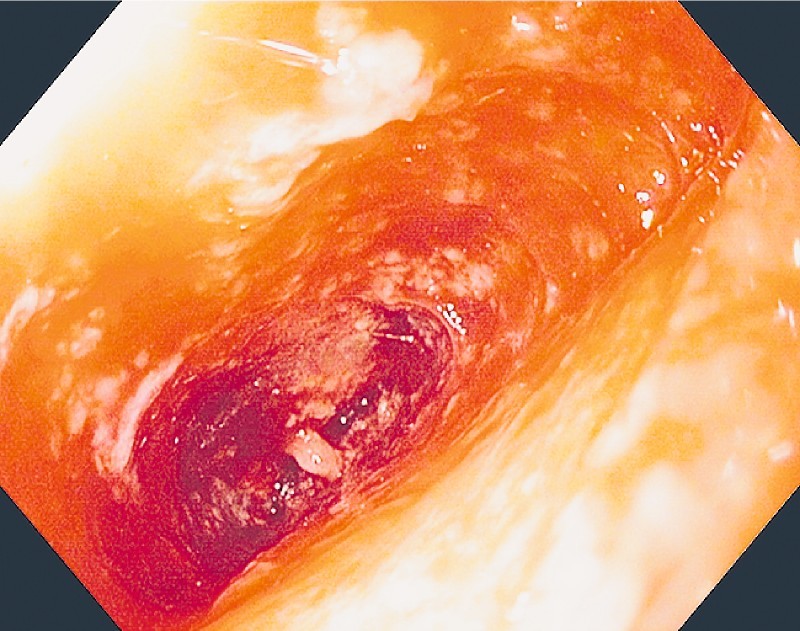

Fig. 2.

Granulation tissue, after 10 days of treatment.

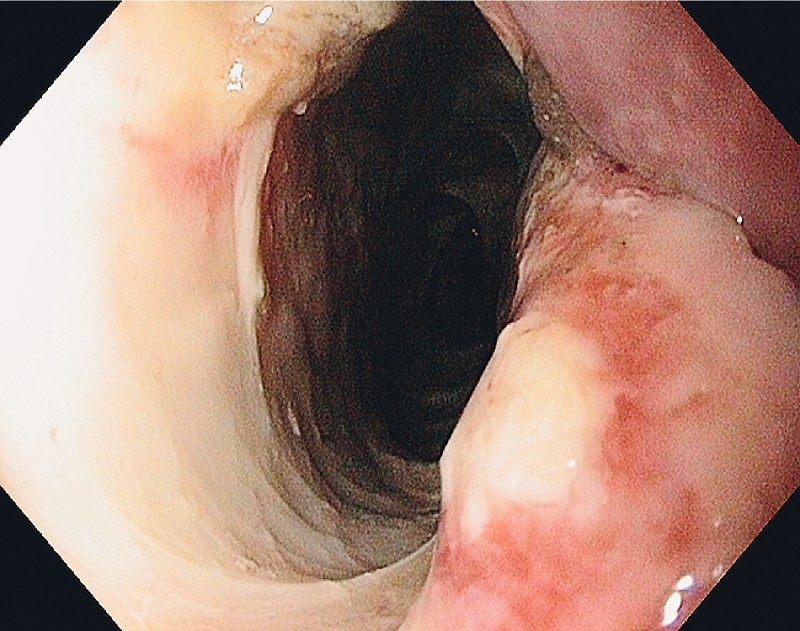

Fig. 3.

The entrance to the mediastinal cavity on Day 1.

Fig. 4.

A small residual recess can be seen in the proximal esophagus on Day 29.

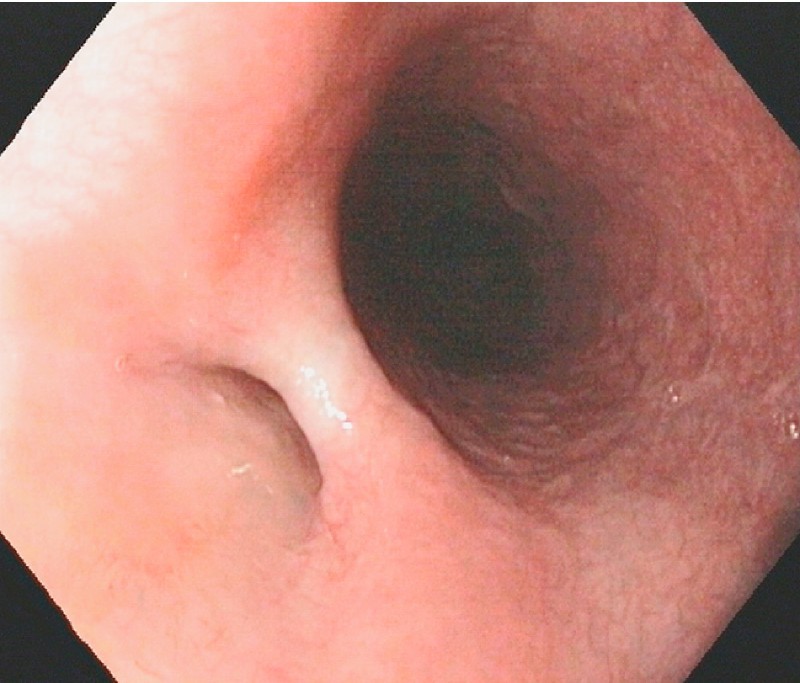

Fig. 5.

EndoSponge in the mediastinal cavity.

A few other types of lesions outside of the esophagus and rectum have also been treated successfully with this method, such as anastomotic insufficiencies in the stomach 18, after pancreaticoduodenectomy 19, in patients with Boerhaave syndrome 20, after duodenal perforation 21 and after bariatric surgery with gastric Roux-Y-bypass 22 (Table 2). A special feature of the present study is that a high proportion of the patients (70 %) were suffering from leakages in the proximal part of the esophagus; in two patients, the perforation tear had even reached the piriform recess.

Table 2. Current literature.

| Author | Journal | Title | No. of patients |

| Wedemeyer J, Schneider A, Manns MP et al. | Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2008; 67: 708 – 711 | Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of upper intestinal anastomotic leaks | 2 |

| Loske G; Müller C. | Zentralblatt für Chirurgie 2009; 134: 267 – 270 | Vakuumtherapie einer Anastomoseninsuffizienz am Osophagus--ein Fallbericht | 1 |

| Ahrens M, Schulte T, Egberts J et al. | Endoscopy 2101; 42: 693 – 698 | Drainage of esophageal leakage using endoscopic vacuum therapy: a prospective pilot study | 5 |

| Loske G, Schorsch T, Mueller CT | Endoscopy 2010; 42 Suppl 2: E109 | Endoscopic intraluminal vacuum therapy of duodenal perforation | 1 |

| Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C | Endoscopy 2010; 42 Suppl 2: E144 – 145 | Endoscopic intracavitary vacuum therapy of Boerhaave's syndrome: a case report | 1 |

| Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C | Surgical endoscopy 2010; 24: 2531 – 2535 | Endoscopic vacuum sponge therapy for esophageal defects | 10 |

| Wallstabe I, Plato R, Weimann A | Endoscopy 2010; 42 Suppl 2: E165 – 166 | Endoluminal vacuum therapy for anastomotic insufficiency after gastrectomy | 1 |

| Wedemeyer J, Brangewitz M, Kubicka S et al. | Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2010; 71: 382 – 386 | Management of major postsurgical gastroesophageal intrathoracic leaks with an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system | 8 |

| Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C | Endoscopy 2011; 43: 540 – 544 | Intraluminal and intracavitary vacuum therapy for esophageal leakage: a new endoscopic minimally invasive approach | 14 |

| Schniewind B, Schafmayer C, Both M et al. | Endoscopy 2011; 43 Suppl 2 UCTN: E64 – 65 | Ingrowth and device disintegration in an intralobar abscess cavity during endosponge therapy for esophageal anastomotic leakage | 1 |

| Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I | Endoscopy 2011; 43 Suppl 2 UCTN: E312 – 314 | Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst | 1 |

| Loske G, Strauss T, Riefel B et al. | Endoscopy 2012; 44 Suppl 2 UCTN: E94 – 95 | Endoscopic vacuum therapy in the management of anastomotic insufficiency after pancreaticoduodenectomy | 1 |

| Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I | Endoscopy 2012; 44 Suppl 2 UCTN: E49 – 50 | Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of infected pancreatic pseudocyst using a coated sponge | 1 |

| Brangewitz M, Voigtländer T, Helfrit, FA et al. | Endoscopy 2013;45:433 – 438 | Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, a retrospective analysis | 32 |

| Gubler C, Schneider PM, Bauerfeind P | Diseases of the esophagus 2013; 26: 598 – 602 | Complex anastomotic leaks following esophageal resections: the new stent over sponge (SOS) approach | 2 |

| Schniewind B, Schafmayer C, Voehrs G et al. | Surgical endoscopy 2013; 27: 3883 – 3890 | Endoscopic endoluminal vacuum therapy is superior to other regimens in managing anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy: a comparative retrospective study | 17 |

| Schorsch T, Müller C, Loske G | Endoscopy 2013; 45 Suppl 2 UCTN :E141 – 142 | Pancreatico-gastric anastomotic insufficiency successfully treated with endoscopic vacuum therapy | 1 |

| Schorsch T, Müller C, Loske G | Surgical endoscopy 2013; 27: 2040 – 2045 | Endoscopic vacuum therapy of anastomotic leakage and iatrogenic perforation in the esophagus | 24 |

| Bludau M, Hölscher AH, Herbold T et al. | Surgical endoscopy 2014; 28: 896 – 901 | Management of upper intestinal leaks using an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system (E-VAC) | 14 |

| Fähndrich M, Sandmann M | Endoscopy 2014; 46 Suppl 1 UCTN: E459 | A new method for endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis through a gastrostomy site using an endosponge | 1 |

| Heits N, Stapel L, Reichert B et al. | The Annals of thoracic surgery 2014; 97: 1029 – 1035 | Endoscopic endoluminal vacuum therapy in esophageal perforation | 10 |

| Kronsbein H, Etzold M, Fein M et al. | Endoscopy 2014; 46 Suppl 1 UCTN: E485 – 486 | Endoscopic vacuum therapy for acute esophageal perforation following pneumatic dilation | 1 |

| Loske G, Schorsch T, Schmidt-Seithe T et al. | Endoscopy 2014; 46 Suppl 1 UCTN: E575 –57 6 | Intraluminal endoscopic vacuum therapy in a case of ischemia of the blind end of the jejunal loop after Roux-en-Y gastrectomy | 1 |

| Möschler O, Müller MK | Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie 2014; 52: 281 – 284 | Endoluminal vacuum therapy for iatrogenic perforation of the proximal oesophagus | 2 |

The complexity of perforations in the proximal esophagus is greater than in the distal esophagus, because surgery is much more invasive and stent placement involves the risk of impairing the airway. In the present group of patients, management of the airway in patients with very proximally located perforations (patients 4 and 7, Table 1) was only achieved using general anesthesia during the whole course of treatment, for 5 days. This strategy is accompanied by a risk of the development of respirator-associated pneumonia, as was observed in patient no. 4. In other patients, it was possible to carry out sponge changes only under general anesthesia, due to the proximity of the lesions to the airway.

This and the fact that placement of the sponge requires a high degree of endoscopic skill indicates that endoscopic vacuum therapy should only be performed in high-volume centers with expertise in interventional endoscopy and intensive-care medicine. Treatment decisions should be made by an interdisciplinary team including visceral surgeons, radiologists, and endoscopists in order to discuss the different treatment options.

The major disadvantage in evaluating this promising new technique is the absence of comparative studies, due to the complexity of the subject and the large number of different treatment options possible – such as various types of surgical interventions and different types of stent and clip devices. Therefore it is not possible to recommend this new method as first-line treatment in management of all leaks and perforations of the esophagus.

Brangewitz et al. reported on a retrospective comparative study including 32 patients who received EVT and 39 patients who underwent stent treatment, with mortality rates of 15 % and 25 %, respectively 23. The other comparative study available (Schniewind et al.) compared the outcomes of patients with postsurgical esophageal defects and systemic inflammation and reported statistically significant differences in the mortality rates among patients with surgical repair, stent placement, or endoscopic vacuum therapy: 50 %, 83 %, and 12 %, respectively 24. A limitation of this study is its retrospective data collection without randomization of the patients.

Limitations of the present study include the small sample size of 10 patients, differences in the underlying causes of the esophageal wall defects, and a lack of comparison with other treatment modalities. A large-scale multicenter study would be mandatory in order to overcome these limitations, because the occurrence of esophageal perforations and leaks is fortunately a rare event.

EVT for defects in the esophageal wall is a valuable tool in the management of this high-mortality condition and should be taken into consideration by surgeons and gastroenterologists when discussing treatment options in these patients. Prospective and comparative studies are required in order to further evaluate the significance of this new minimally invasive approach.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Michael Robertson for his skilled linguistic revision of the document.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Lang H, Piso P, Stukenborg C. et al. Management and results of proximal anastomotic leaks in a series of 1114 total gastrectomies for gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:168–171. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orive-Calzada A, Calderón-García Á, Bernal-Martínez A. et al. Closure of benign leaks, perforations, and fistulas with temporary placement of fully covered metal stents: a retrospective analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014. 24:528–36. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318293c4d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swinnen J, Eisendrath P, Rigaux J. et al. Self-expandable metal stents for the treatment of benign upper GI leaks and perforations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:890–899. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasari B V, Neely D, Kennedy A. et al. The role of esophageal stents in the management of esophageal anastomotic leaks and benign esophageal perforations. Ann Surg. 2014;259:852–860. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qadeer M A, Dumot J A, Vargo J J. et al. Endoscopic clips for closing esophageal perforations: case report and pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changela K, Virk M A, Patel N. et al. Role of over the scope clips in the management of iatrogenic gastrointestinal perforations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11460–11462. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohl J, Borgulya M, Lorenz D. et al. Endoscopic closure of postoperative esophageal leaks with a novel over-the-scope clip system. Endoscopy. 2010;42:757–759. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson J B, Sorser S A, Atia A N. et al. Repair of esophageal perforations using a novel endoscopic suturing system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:535–537. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Bernstorff W, Glitsch A, Schreiber A. et al. ETVARD (endoscopic transanal vacuum-assisted rectal drainage) leads to complete but delayed closure of extraperitoneal rectal anastomotic leakage cavities following neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:819–825. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagell C F, Holte K. Treatment of anastomotic leakage after rectal resection with transrectal vacuum-assisted drainage (VAC). A method for rapid control of pelvic sepsis and healing. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:657–660. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman R K, Ascioti A J, Giannini T. et al. Analysis of unsuccessful esophageal stent placements for esophageal perforation, fistula, or anastomotic leak. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:959–964; discussion 964-965. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Boeckel P G, Dua K S, Weusten B L. et al. Fully covered self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), partially covered SEMS and self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of benign esophageal ruptures and anastomotic leaks. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eroglu A, Turkyilmaz A, Aydin Y. et al. Current management of esophageal perforation: 20 years experience. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:374–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biancari F, D’Andrea V, Paone R. et al. Current treatment and outcome of esophageal perforations in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of 75 studies. World J Surg. 2013;37:1051–1059. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bemelman W A. Vacuum assisted closure in coloproctology. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:261–263. doi: 10.1007/s10151-009-0543-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of infected pancreatic pseudocyst using a coated sponge. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E49–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallstabe I, Tiedemann A, Schiefke I. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst. Endoscopy. 2011;43:E312–313. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallstabe I, Plato R, Weimann A. Endoluminal vacuum therapy for anastomotic insufficiency after gastrectomy. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E165–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loske G, Strauss T, Riefel B. et al. Endoscopic vacuum therapy in the management of anastomotic insufficiency after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E94–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C. Endoscopic intracavitary vacuum therapy of Boerhaave’s syndrome: a case report. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E144–145. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loske G, Schorsch T, Mueller C T. Endoscopic intraluminal vacuum therapy of duodenal perforation. Endoscopy. 2010;42:E109. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seyfried F, Reimer S, Miras A. et al. Successful treatment of a gastric leak after bariatric surgery using endoluminal vacuum therapy. Endoscopy. 2013;45:E267–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brangewitz M, Voigtländer T, Helfritz F A. et al. Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:433–438. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schniewind B, Schafmayer C, Voehrs G. et al. Endoscopic endoluminal vacuum therapy is superior to other regimens in managing anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy: a comparative retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3883–3890. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]