Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei (T. brucei) is responsible for the fatal human disease called African trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness. The causative parasite, Trypanosoma, encodes soluble versions of inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPase), also called vacuolar soluble proteins (VSPs), which are localized to its acidocalcisomes. The latter are acidic membrane-enclosed organelles rich in polyphosphate chains and divalent cations whose significance in these parasites remains unclear. We here report the crystal structure of T. brucei brucei acidocalcisomal PPases in a ternary complex with Mg2+ and imidodiphosphate. The crystal structure reveals a novel structural architecture distinct from known class I PPases in its tetrameric oligomeric state in which a fused EF hand domain arranges around the catalytic PPase domain. This unprecedented assembly evident from TbbVSP1 crystal structure is further confirmed by SAXS and TEM data. SAXS data suggest structural flexibility in EF hand domains indicative of conformational plasticity within TbbVSP1.

Keywords: crystal structure, electron microscopy (EM), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS), Trypanosoma brucei

Introduction

African trypanosomiasis, commonly known as sleeping sickness, affects ∼50,000 inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa yearly (1) with 60 million people at risk of infection (2). Sleeping sickness is caused by two subspecies of T. brucei: T. brucei gambiense and T. brucei rhodesiense. The former alone accounts for ∼98% of the cases in humans and livestock (1). T. brucei brucei is another subspecies of T. brucei that is used as an experimental model in laboratory to study sleeping sickness, and this parasite infects animals causing a disease called nagana (3). Left untreated, sleeping sickness is fatal, and there are currently two drugs used to treat the initial phase of the disease: suramin and pentamidine. These are employed in treatment of trypanosomiasis caused by T. brucei rhodesiense and T. brucei gambiense infections (4). For the treatment of second or neurological phase, an arsenic-based drug called melarsopol is used. However, this drug causes severe side effects and can sometimes be lethal (5). A newer and much more expensive drug, eflornithine, is effective only against T. brucei gambiense. (6). A combination of another drug, nifurtimox, with eflornithine has been used for treatment, but unfortunately it is not effective against T. brucei gambiense (6). Therefore, there is a pressing case to find new, safe, inexpensive, and broad spectrum drugs for treating sleeping sickness in humans and livestock.

Soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (PPase, EC 3.6.1.1)3 is a ubiquitous and essential enzyme that hydrolyzes the PPi generated during cellular processes such as DNA replication and protein translation (7–9). Soluble PPases comprise two families that differ in both sequence and structure (10, 11). Family/class I PPases occur in all types of cells from bacteria to humans, whereas class II occurs exclusively in bacteria (11–12). Both classes of enzymes require divalent metal cations for catalysis (13–15). PPases from wide sources have been characterized, but those from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli are most well characterized in terms of three-dimensional structures and function.

Acidocalcisomes are acidic organelles rich in short and long chain polyphosphates complexed with Ca+2 and other divalent cations (16). Trypanosomes carry a subset of soluble PPases called vacuolar soluble proteins (VSPs) that localize to acidocalcisomes and are known for their roles in regulation of acidocalcisome phosphate pool via their PPase and tripolyphosphatase activities (17). There is increasing evidence for the functional importance of VSPs for growth and survival of parasites inside their host (17–19). This has resulted in investigation of VSP as potential inhibitor target and has also highlighted the importance of acidocalcisomal proteins in general (20). A study has shown that small molecule inhibitors of VSP tripolyphosphatase activity can provide protective effects against T. brucei infection in a mouse model (21). However, these inhibitors suffer from poor IC50 values, and further improvement has been suggested for generating more potent compounds. VSPs have mostly been explored from cellular and biochemical perspectives to date, despite the pivotal role of structure-based drug development in modern infectious disease drug discovery (22).

Here, we present the crystal structure of T. brucei brucei VSP1 (TbbVSP1) at 2.35 Å resolution in complex with Mg+2 and IDP. Our analyses reveal an unusual tetrameric quaternary association of TbbVSP1 when compared with other known class I PPases that adopt dimeric or hexameric states. Our TbbVSP1 tetramer structure has been confirmed by SAXS and EM experiments, which indicate flexibility in the EF hands within this protein. This is the first study of structural characterization of an acidocalcisomal protein from protozoan parasites to our knowledge, and provides new structural insights into class I PPases. Our work provides a foundation for further functional dissection and pharmacological exploitation of VSPs.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning, Overexpression, and Purification of TbbVSP1

The ORF corresponding to full-length TbbVSP1 containing EF hand domain (residues 1–160) and PPase domain (residues 161–414) was optimized for expression in E. coli and cloned into pETM11 vector using NcoI and KpnI restriction sites. Briefly, bacterial cells were lysed by sonication in a buffer containing protease inhibitor mixture. Affinity purification was performed on a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (His-Trap FF; GE Healthcare) column using AKTA-FPLC system (GE Healthcare). The His6 tag of the protein was removed with TEV protease followed by dialysis in low salt buffer (30 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 25 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT), and it was subsequently applied to Q-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for further purification and removal of TEV protease by anion exchange chromatography. Purest fractions were pooled and saturated with ammonium sulfate to a final concentration of 1 m, and further polishing and purification was achieved by hydrophobic interaction chromatography on a phenyl FF 16/10 column (GE Healthcare). Finally, purest fractions were pooled and concentrated to 10 mg ml−1 with 10-kDa cutoff centrifugal devices (Millipore) followed by gel permeation chromatography on S200–16/60 column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer containing 30 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7.2, 50 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT.

Analytical Size Exclusion Chromatography

Oligomerization of TbbVSP1 was examined using analytical size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 HR 10/300; GE Healthcare) in 30 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 500 mm NaCl, and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol. A total of 500 μl of full-length TbbVSP1 at concentration of 4 mg ml−1 was applied to the column; separately, 100 μl of N-terminally truncated TbbVSP1 at concentration of 0.5 mg/ml was injected into size exclusion chromatography column. The molecular mass standards used for this study (blue dextran (∼2000 kDa), ferritin (∼400 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), conalbumin (74 kDa), ovalbumin (66 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), ribonuclease (12 kDa), and apoprotinin (6 kDa) were purchased from GE Healthcare. A standard curve was generated by plotting relative elution volume Kav against log10 molecular mass for each standard marker. The curve was fitted to a linear equation, and the apparent molecular masses were deduced from Kav for respective proteins.

Crystallization of TbbVSP1

A single peak corresponding to tetramer in gel permeation chromatography was collected followed by the addition of 3 mm MgCl2 and 0.5 mm imidodiphosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) to protein (concentrated to 30 mg ml−1) solution for co-crystallization. Initial crystallization trials were performed at 293 K by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method using commercially available crystallization screens. Single cuboid shaped crystals were obtained within 4 days from MORPHEUS screen (Molecular Dimensions) in a solution containing 10% PEG 8000, 20% ethylene glycol, 0.03 m halide, and 0.1 m bicine/trizma pH 8.3. Further optimization of solution conditions to 9% PEG 8000, 18% ethylene glycol, 0.02 m halide, 0.1 m bicine/trizma, pH 8.0, and 0. 1 m spermine tetrahydrochloride produced diffraction quality crystals.

Data Collection, Structure Solution, and Analysis

X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted at BM14 European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France), and data were collected using synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.953 Å) on a MAR CCD225 detector at 100 K. A total of 270 images were collected and processed to 2.35 Å using HKL2000 (23). The PPase domain of TbbVSP1 shares 65% sequence homology with yeast PPase, and therefore the structure of TbbVSP1 was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (24) with yeast PPase (PDB code 1M38) as a template. Initially, model was built using AutoBuild in PHENIX (25), which was further subjected to several rounds of manual building and refinement performed using COOT and phenix.refine respectively. An EF hand domain was built manually into electron density maps. Imidodiphoshate and coordinating Mg+2 ions were added during the manual model building, and ligand density was verified using SA-OMIT maps. The overall stereochemical quality of the built model was assessed using MolProbity (26) and with PDB validation server. All structural figures were generated with PyMOL and Chimera (27). The coordinates for TbbVSP1.PNP.Mg+2 complex have been deposited with Protein Data Bank with accession code 5C5V.

Small Angle X-ray Scattering Experiments

SAXS experiments were conducted at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility BioSAXS Beamline BM29 in Grenoble, France (28). Highly purified protein (>95% purity) was used, measurements for 30 μl of protein solution at five different concentrations (8.6, 4.3, 2.1, 1.08, and 0.54 mg ml−1) for each sample (and buffer) were defined using the ISPyB BioSAXS interface (29), and the sequence was triggered via BsxCuBE. Ten individual frames were collected for every exposure, each 2 s in duration using the Pilatus 1 m detector (Dectris). Individual frames were processed automatically and independently within the EDNA framework, yielding individual radially averaged curves of normalized intensity versus scattering angle s = 4π sin (θ)/λ. The data were processed and merged using PRIMUS (30) and ATSAS package (31), and pair distribution function was computed using GNOM (32). The ab initio models were calculated for each construct using DAMMIF (33) and then averaged, aligned, and compared (which showed minimal variation) using DAMAVER (34). Rigid body modeling of the complex was complicated by the internal cavities that caused artifacts in the calculation of theoretical experimental curves. Therefore, ensemble modeling (35) was used to generate 10,000 models allowing random movements, and the resulting models were screened using Pepsi-SAXS.4 The resulting representative model and ab initio models for each construct selected by DAMAVER were overlaid using PyMOL. The fits to the experimental data of the models and the theoretical scattering of the structures were prepared with SAXSVIEW.

Electron Microscopy

Small aliquots (3.5 μl) of diluted protein (0.025 mg ml−1) were deposited on carbon-coated electron microscope grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Specimens were observed using a JEOL JEM2100 LaB6 at a nominal magnification of ×39600 with a pixel size of 3.5 Å at the given magnification. Pictures were recorded using a GATAN 2K × 2K cameras. A total of 5268 particles were selected, normalized using EMAN software (36), and classified using SPIDER (37) and K-means classification. The average classes obtained were compared with the two-dimensional projections of three-dimensional crystal structure of TbbVSP1 filtered at 30 Å obtained using the PJ 3Q function in SPIDER.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

All ITC experiments were performed on a GE-Micro Cal ITC 200, and Origin was used for data analysis. Direct titration of EF hand domain of TbbVSP1 with Ca+2 was done in 50 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7.2, and 50 mm NaCl. Before titration, the protein was made divalent cation free and decalcified using sequential treatment of first 10 mm EDTA followed by dialysis against decreasing concentrations of EGTA (20 to 0.5 mm). Finally, the protein was dialyzed against experimental buffer (30 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7.2, and 100 mm NaCl) prepared in deionized water. Ca+2 solutions were prepared by diluting 1 m CaCl2 stock solution with dialysate/experimental buffer. A typical titration was carried over 40 injections with initial injection of 0.4 μl followed by 39 injections of 1 μl of 0.2 mm Ca+2 into protein solution (50 μm) with 150-s intervals between injections and 750 rpm stirring speed. Independent titrations were performed at 25 and 30 °C. All titrations were done twice, and the values are reported in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Thermodynamic parameters of EF hand-Ca+2 interactions

| Temperature | N | Ka | Kd | ΔH | ΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 107m−1 | nm | kcal/mol | cal/mol °C | ||

| 25 °C | 1.07 ± 0.002 | 1.55 ± 0.18 | 64.5 ± 5.5 | −5.25 ± 0.21 | 14.3 |

| 30 °C | 1.06 ± 0.005 | 1.43 ± 0.13 | 69.9 ± 7.7 | −5.36 ± 0.56 | 11.9 |

Results

Domain Analysis and Characterization of TbbVSP1

The T. brucei brucei genome contains two isoforms of VSPs present on chromosome XI: TbbVSP1 (TriTrypDB ID Tb927.11.7060, characterized in this study) and TbbVSP2 (TriTrypDB ID Tb927.11.7080). Both forms are nearly identical and diverge only in three amino acids (F32V, S32L, and L33H). Sequence and domain analysis shows that TbbVSP1 belongs to class I PPases with best identity with animal/fungal PPases in the C-terminal region, but it also contains an EF hand domain in the N-terminal region (Fig. 1a). In particular, this EF hand domain is present in all VSPs of kinetoplastida parasites (Fig. 1a). TbbVSP1 ORF encodes a protein of 414 amino acids with relative molecular mass of 47.2 kDa. Nevertheless, native size analysis by gel permeation chromatography indicated that both full-length and N-terminal truncated TbbVSP1 (residues 160–414; PPase domain) predominantly elute as tetramers with molecular masses of 183 and 138 kDa respectively, suggesting that PPase domain is sufficient for tetramer formation in solution (Fig. 1b). This is in contrast to animal/fungal PPases that associate as dimers (38). Because of the putative EF hand domain in the N-terminal region of the protein, we tested effect of divalent cations on protein oligomerization state. Gel permeation chromatography data indicated that addition of Ca+2 and Mg+2 had no influence on oligomeric stoichiometry of TbbVSP1 (Fig. 1b, top panel). Thus, collectively these data suggested that TbbVSP1 possesses an unusual and specific structural organization, which is different from conventional class I PPases.

FIGURE 1.

Domain organization and crystal structure of TbbVSP1. a, schematic representation of domain structures of VSPs and other class I PPases. The EF hand domain (yellow), PPase domain (blue), and interdomain region (red) are colored; domain boundaries are based on x-ray crystal structures. b, top panel depicts size exclusion chromatography elution profile/peaks of full-length TbbVSP1, monitored by absorbance at 280 nm. Peaks are color-coded according to divalent cations mixed with the protein: red, mixed with Ca+2; brown, mixed with Mg+2; and blue, with EDTA/no divalent cation. Standard molecular mass markers are indicated by green arrows on elution volume axis. The middle panel shows the line curve obtained with protein standard markers, which was fitted to a linear equation for calculating molecular masses (see “Experimental Procedures”). Kav values for full-length TbbVSP1 (red) and its EF hand deletion mutant (blue) are indicated. The bottom panel depicts size exclusion chromatography profile of EF hand deletion TbbVSP1. The deletion mutant is shown by domain schematic labeled with boundaries, and the tetrameric peak is indicated with the molecular masses noted in parentheses. c, ribbon representation of crystal structure of TbbVSP1 monomer with individual domains colored same as in the schematic. Secondary structures elements are labeled: h for helix and β for strand. The lower panel shows conformational difference in the bridge helix, revealed upon superposition of individual subunits in the asymmetric unit.

Crystal Structure of TbbVSP1

The TbbVSP1 crystallized in tetragonal space group (P42212), and its structure was solved using molecular replacement method with yeast PPase as template (PDB code 1M38). Electron density for most of the residues was generally good; however, residues 1–71 were not traceable in the model because of poor or no electron density. The final refinement and statistical parameters are stereochemically sound (Table 1). The crystal structure of TbbVSP1 reveals bidomain architecture (Fig. 1c). A DALI search against PDB using the complete structure of TbbVSP1 failed to identify any structure with significant similarities over entire polypeptide, suggesting a unique overall architecture. However, searches using individual domains revealed closest structural homolog of the N-terminal domain (residues 72–142) as EF hand calcium binding protein (PDB code 2BE4; Z = 8.2), and for C-terminal domain (residues 167–414) the yeast PPase (PDB code 1E6A; Z = 33.3). Therefore, hereon we refer to the N- and C-terminal domains as EF hand and PPase domains respectively. The EF hand domain has a compact globular fold and consists of four α-helices, h1–h4 (residues 75–87, 98–108, 118–125, and 133–142) (Fig. 1c). The PPase domain consists of a five-stranded β barrel made from strands β4 and β7–β10 in the core region, and in addition a β sheet is formed away from the core by strands β1–β3. The β-barrel is flanked by two long α-helices, h8 and h11, three short 310 helices (residues 341–343 (h6), 370–372 (h9), and 380–382 (h10)) and helix h7, which is a combination of a 310 helix and α helix. The h7 lies at the base of the β-barrel. The EF hand and PPase domain are bridged via a 24-residue interdomain region (residue 145–165). The interdomain region is composed of a helix (“bridge helix,” residues 145–159) present at the base of the EF hand domain followed by a small unstructured region (residues 160–165) that leads into PPase domain (Fig. 1c). Overall folds of two TbbVSP1 protomers in the asymmetric unit are similar. However, an approximately 12° orientation shift is observed at bridge helix (Fig. 1c, bottom panel), which suggests flexibility in this region.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

The values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| TbbVSP1-Mg-PNP | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P42212 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 104.2, 104.2, 215.5 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Rmerge(%) | 0.07 (0.69) |

| I/σ(I) | 32.8 (2.71) |

| Completeness | 98.1 (97.2) |

| Redundancy | 10.9 (11.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution | 39.8–2.35 |

| No. of Reflections | 49,471 (3366) |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 19.9/23.8 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 5580 |

| Ligand/Ions | 20/15 |

| Water | 200 |

| B-factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 64 |

| Ligand/Ions | 56/59 |

| Water | 59 |

| rmsd | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.0073 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.061 |

Quaternary Structure of TbbVSP1

The protomers in asymmetric unit make contact via their PPase domain and extend EF hand domain in opposite directions, thus presenting an inward facing concave surface (Fig. 2a). The tetramer can be generated by application of 2-fold crystallographic operator resulting in a dimer of dimers assembly (Fig. 2b). The assembly contains two dimers, AB and A′B′, where each uses its concave surface to intimately lock with another to form a tetramer of 84 × 72 × 120 Å dimensions. The central core of the tetramer contains PPase domains, whereas EF hand domains jut out in the oligomeric assembly (Fig. 2c). This assembly is stabilized by four unique intersubunit interfaces (interface I–IV). Interface I (1840 Å2) and II (700 Å2) are hydrophilic, whereas interface III (825 Å2) and IV (300 Å2) are hydrophobic in nature (Fig. 3a). As indicated by buried surface areas, interface I is much more extensive than other interfaces and involves interaction between residues from PPase domain and interdomain region of monomers A-A′ or B-B′ (Fig. 3b). Interface II is majorly formed by contacts between EF hand and PPase domains of two protomers (Fig. 3c). Crystal structure showed that His92 of EF hand domain forms a salt bridge with Asp396 present on h11 of PPase domain, and this could be an important contributing factor to stability of this interface. In addition, the bridge helix also makes contribution to interface II stability via Asp158, which makes a salt bridge with Arg410 of h11 (Fig. 3c). Interface III involves interaction between monomer A-B or A′-B′, which is braced by hydrophobic stacking interactions between Trp233 and Trp268 (Fig. 3d) and further stabilized by hydrogen bonding and N-H … π between Arg235 and His263 residues. Further, the aromatic ring stacking interactions between Phe343 and Phe353 are observed at interface IV (Fig. 3e). Phe343 and Phe353 are highly conserved among VSPs, suggesting that interface IV is another specific feature of TbbVSP1. Thus, these interactions demonstrate extensive connections between the monomers of the assembly. In line with above, the theoretical free energy value estimated for the assembly by PISA (ΔGdiss = 26.5 kcal mol−1) identified the tetramer as stable. This oligomer is further confirmed by SAXS and EM (see below) data.

FIGURE 2.

Dimer of dimers assembly of TbbVSP1. a, two views of the dimer in asymmetric unit with 2-fold noncrystallographic (NCS) axis colored green. The PPase domain (blue), EF hand domain (yellow), and interdomain region (red) are highlighted. b, schematic representation of tetrameric TbbVSP1 assembly containing two dimers: A-B and A′-B′. A-B is highlighted domain-wise as in panel a, and similarly A′-B′ domains (orange), the EF hand domain (cyan), and the interdomain region (pink) are colored. The 2-fold crystallographic symmetry (CS) axis is highlighted in purple. c, multiple molecular surface views of the tetramer. The colors of different domains are same as in Fig. 2b.

FIGURE 3.

Intermolecular interactions within TbbVSP1 tetramer subunits. a, schematic of the tetramer of TbbVSP1 showing interfaces in the crystal lattice. Circles showing interface regions are color-coded: blue as hydrophilic interface and green as hydrophobic interface. b–e, view of intersubunit contacts with important residues shown as sticks. Interactions are shown as dotted lines, and residues in salt bridges are marked with asterisks. The stacking/π … π edge to face, face to face interactions and N-H … π interactions were calculated/measured from centroids of aromatic rings that are shown as green spheres.

SAXS Reveals Conformational Flexibility of TbbVSP1

To study solution structure of TbbVSP1, we conducted SAXS studies with highly pure full-length protein. The Guinier plot of TbbVSP1 exhibits good linearity (Fig. 4a), suggesting the protein solution was free of large aggregates or higher molecular mass contaminants. The molecular masses estimated from experimental volume and ab initio envelopes are 150–200 and 203 kDa respectively, which correlate well with values expected for a tetrameric species. However, the experimental volume estimated from ab initio modeling (302 ± 50 nm3) does not correlate with volume from tetramer crystal structure (248 nm3). This increase in volume is likely to be a result of flexibility in TbbVSP1 structure in solution state. We further noticed difference in Dmax between SAXS (157 ± 3 Å) and the crystal structure (120 Å), suggesting again that the crystal structure described a compact conformation for this protein. To investigate the SAXS curves at molecular level, we probed the tetrameric crystal structure model, but it did not fit with experimental SAXS curves (the associated χ2 were >10). Consistent with this observation, the overlay of tetrameric crystal structure form produced poor fits with the SAXS envelope. We further noticed that PPase domains docked nicely into the core region of the envelope but the peripheral EF hand domains fit poorly and in fact protruded outside the envelope. Considering the increase in size observed by SAXS, we attributed this disagreement to absence of flexibility in our atomic model based on crystal structure data.

FIGURE 4.

SAXS analysis of TbbVSP1 solution structure indicates flexibility. a, Guinier plot from raw data recorded at a range of protein concentrations. b, Individual domains of homodimer subunits in the asymmetric unit are superimposed. EF hand domains show more conformational variation relative to the PPase domains. c, SAXS curve showing logarithm of scattered intensity plotted as a function of momentum transfer, s = 4π sin (θ) λ−1, where θ is the scattering angle, and λ is the x-ray wavelength. d, two views of TbbVSP1 model (PPase domains (blue sticks) and EF hand domain (orange sticks)) in solution by SAXS overlaid on ab initio low resolution envelope colored in green. e, left panel shows temperature factor variation in TbbVSP1 crystal structure colored from low to high values (40–105 Å2) where arrows indicate the bridge helix. The right panel shows sequence conservation in the bridge helix region where residue positions with highest variability are boxed.

In line with the above, alignment of homodimer subunits in the asymmetric unit identified a significant difference in the positioning of EF hand domains (rmsd 0.75 Å for 70 Cα atoms) and bridge helices (rmsd 1.3 Å, for 18 Cα atoms; Figs. 4b and 1c, bottom panel). However, PPase domains did not display significant deviation (rmsd 0.12 Å for 247 Cα atoms; Fig. 4b). These observations collectively suggest inherent flexibility in EF hand domain and bridge helix with respect to the PPase domain backbone. Therefore, to assess the likelihood that crystal packing may stabilize a more flexible structure, we deployed an ensemble modeling (EOM) approach to predict the likely flexible movements and multiple conformations in solution by allowing hinge motions in EF hand domain. We also tested the bridge helix as a potential source of hinge motion, which could act as pivot between EF hand domain and PPase domain. Indeed, we found that the hinge motion produces better fit to the SAXS data (χ2 = 2.22) (Fig. 4c). Overlay of model into ab initio envelope indicates that EF hand domains bend toward each other about the PPase domains, which hold together the tetramer core preventing it dissociating into lower oligomeric state (Fig. 4d). Although a single atomic model suffices to explain the experimental SAXS curve, this atomic state may represent a true dominant conformation in solution or an average of an ensemble spanning a subset of conformational spaces. Either of the above interpretation indicates structural malleability of TbbVSP1 in solution in the absence of external forces such as those exerted by crystal packing.

Finally, crystal structure derived B-factors display a gradient along the body of bridge helix ranging from low (proximal to PPase domain) to high (near the base of EF hand domain, contributed by Val145, His146 and Ser147). In the tetrameric crystal structure, these residues have limited contacts with other regions and are least conserved among VSPs. These two attributes indicate a dynamic tether or flexibility in the hinge region (Fig. 4e), consistent with the discussion so far.

TEM Studies

For direct visualization of tetramer complex, we performed negative staining TEM to produce two-dimensional projections of single particles using highly pure (>95%) TbbVSP1. The gel filtration profile of material used for EM was the equivalent tetramer fraction that was used in crystallization and SAXS analyses. For TEM, 80 micrographs of the sample were taken, and 5268 particles were selected with a typical micrograph presented (Fig. 5a). The particles were classified as described under “Experimental Procedures,” along with representative classes (Fig. 5b). Different classes were compared with the two-dimensional projections performed from three-dimensional crystal structure (Fig. 5, b and c), and a good correlation between classes and two-dimensional projections was observed. Finally, we studied the corresponding three-dimensional view of TbbVSP1 to confirm the orientation of the particles. Thus, particles observed in TEM by negative staining are consistent with the three-dimensional crystal structure presented here (Fig. 5, d and e).

FIGURE 5.

TEM studies. a, typical micrograph as observed in TEM (negative staining) with nominal magnification of 39,600× where the scale bar represents 50 nm. b, class averages of TbbVSP1. c, corresponding 2D projections. d, volume view of the three-dimensional crystal structure filtered at 30 Â. The box size is 180 Å. e, molecular surface view with the coloring scheme as in Fig. 2c.

Electrostatic Potential

The molecular surface of TbbVSP1 tetramer displays a bipolar distribution of electrostatic potential. A highly negatively charged pocket concentrated on the distal face of the tetramer whereas positively charged pockets are formed near the tetramer inner core, toeing the tetramer midline (Fig. 6a). The negatively charged pocket consists of clusters of multiple aspartate residues (Asp291, Asp296, Asp323, and Asp328) and one glutamate residue (Glu239). This charged congregation in appropriate proximity suggests a metal binding site. Structural superposition with other known PPases shows high degree of structural conservation in the arrangement and position of these residues, all of which have been shown in previous studies to coordinate metal ions (38). In contrast, the positive patch results from tetramerization and causes arrangement of basic residues from discontinuous regions of the PPase domain (Fig. 6b). The underlying subset of residues of this pocket are Lys215, Arg223, Gln309, Lys314, Arg342, Lys345, and Lys388 of PPase domain that are present on both faces of the tetramer (Fig. 6b). Lys215, Arg223, Gln309, and Arg342 are buried, whereas Lys314, Lys345, and Lys388 are accessible. All these residues show high conservation in VSP homologs from trypanosome family (Fig. 6c).

FIGURE 6.

Electrostatic surface potential. a, two views of TbbVSP1 tetramer surface potential where blue indicates positive and red indicates negative charge foci, displaying range of ± 12 kT/e. b, zoomed view of basic pocket enveloped in yellow with underlying residues labeled. c, an alignment showing region of VSP sequences from T. brucei brucei (TbbVSP1), T. brucei gambiense (TbgVSP1), T. evansi (TeVSP), T. cruzi (TcVSP), and Leishmania major (LmVSP) containing conserved residues (blue) of the basic pocket; arrows indicate their position in the amino acid sequence.

PPase Activity and Pyrophosphate Binding Site

Studies on T. brucei gambiense have shown that VSP1 (TbgVSP1) is an active PPase (17). Also, the TbbVSP1 PPase domain showed high structural similarity to yeast PPase. Therefore, we examined PPase activity of TbbVSP1 using malachite green assay developed for phosphate estimation in solution (39). At a protein tetramer concentration of 0.15 nm, the PPi hydrolysis rate had a turnover number (kcat) of 294 s−1 at 37 °C (Fig. 7a, left panel). We found that the protein actively hydrolyzes PPi in presence of magnesium in an alkaline pH range (7.8–8.5) with kcat/Km of 1.475 × 107 m−1 s−1, suggesting that activity is physiological. The main roles attributed to EF hand domain are the regulation of cellular activity and/or buffering/transporting calcium (40). To investigate whether EF hand domain has any role in PPi hydrolysis, we also used N-terminal EF hand domain truncated enzyme (Δ166 TbbVSP1) that contains the PPase domain only. The resulting kinetic constants for PPi hydrolysis were similar to full-length protein, suggesting that EF hand was not essential for PPi hydrolysis (Fig. 7a, right panel).

FIGURE 7.

Substrate specificity and pyrophosphate binding pocket of TbbVSP1. a, Michaelis-Menten plot of initial velocity versus substrate concentration for TbbVSP1 (left panel) and Δ166 TbbVSP1 (right panel). Km and kcat values are indicated along with adjusted regression co-efficient (R2) for the curves. b, optimum pH measurement with polyP3. The curves show variation in tripolyphosphatase activity of TbbVSP1 over a pH range of 5.2–9.0 and in the presence of different transition metals (1 mm of Zn+2, Co+2, and Mn+2). A buffer with 30 mm sodium citrate tri-basic dihydrate (pH 5.2–5.8) and 30 mm Bis-Tris propane (pH 6.0–9.0) was used in these experiments. c, inhibition of PPi hydrolysis by Ca+2. PPase activity was determined with increasing concentrations of CaCl2 with substrate (PPi) concentration near Km value (25 μm) and co-factor (3 mm of Mg+2). d, stereo view of Fo − Fc simulated annealing OMIT electron density map contoured at 6σ showing IDP (blue mesh) and Mg2+ (orange mesh) in the active site. e, important interactions between IDP, Mg+2 ions, and protein side chains are shown as dashed lines. Dashed lines with shorter and longer width depict metal coordination and hydrogen bonding, respectively. Protein side chains and IDP are shown as sticks, whereas Mg+2 ions (chartreuse) and water (pale green) are shown as spheres.

It has been suggested that substitution of Mg+2 by transition metal ions results in efficient hydrolysis of tripolyphosphate (polyP3) by class I PPases (41); indeed, we did observe this effect for TbbVSP1 (Table 2). Again, this activity is independent of the EF hand domain. In contrast to PPi hydrolysis, the optimum pH for poly P3 hydrolysis shifted to a neutral pH of 7.1, when Co+2 and Mn+2 were co-factors (Fig. 7b). Interestingly, the same activity was discernable at acidic pH of 6.2 in presence of Zn+2 (Fig. 7b), and this property of TbbVSP1 is in line with previous findings on VSP1 from T. brucei gambiense and Leishmania amazonesis (17–18). The kcat values suggest that overall efficiency of polyP3 hydrolysis by TbbVSP1 in presence of transition metal follows the order Zn+2 > Co+2 > Mn+2 (Table 2). Taking these results together, our data indicate that recombinant TbbVSP1 hydrolyzes inorganic phosphates over a wide pH range of 6.2–8.5.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of polyP3 hydrolysis in the presence of different transition metal co-factors

| Cofactor | Concentration | pH | Km | kcat | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | μm | s−1 | m−1 s−1 | ||

| Zn+2 | 0.5 | 6.2 | 44.8 ± 6.7 | 15.8 ± 3.7 | 3.69 × 105 |

| Co+2 | 1.0 | 7.1 | 96.8 ± 11.2 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 0.75 × 105 |

| Mn+2 | 1.0 | 7.1 | 142.3 ± 24.7 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.91 × 104 |

We were successful in co-crystallizing TbbVSP1 with magnesium and IDP (a slow turnover analog of PPi). Omit maps revealed electron density for IDP and Mg2+ ions at the active site of PPase domain (Fig. 7d). The complex comprises of four Mg2+ ions (M1, M2, M3, and M4) and one IDP molecule, which contain two phosphate groups P1 and P2 (Fig. 7e). The active site consists of residues from loops and β-strands that are highly conserved in PPases. In the complex, phosphate group P1 forms hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions with Arg259 (bidentate interaction), Tyr368 and Lys369, whereas P2 forms hydrogen bonding interactions with Lys237 and Tyr270 of the active site (Fig. 7e). M1 and M2 are coordinated exclusively by protein side chain carboxylates: M1 with Asp291, Asp296, and Asp328 and M2 with Asp296 (Fig. 7e). M3 and M4 are coordinated with phosphate groups of IDP and side chain carboxylates: M3 with Glu239 and M4 with Asp323 and Asp328 (Fig. 7e). Coordination geometry for all Mg+2 ions in the active is nearly octahedral, which we validated using the Check My Metal tool (42).

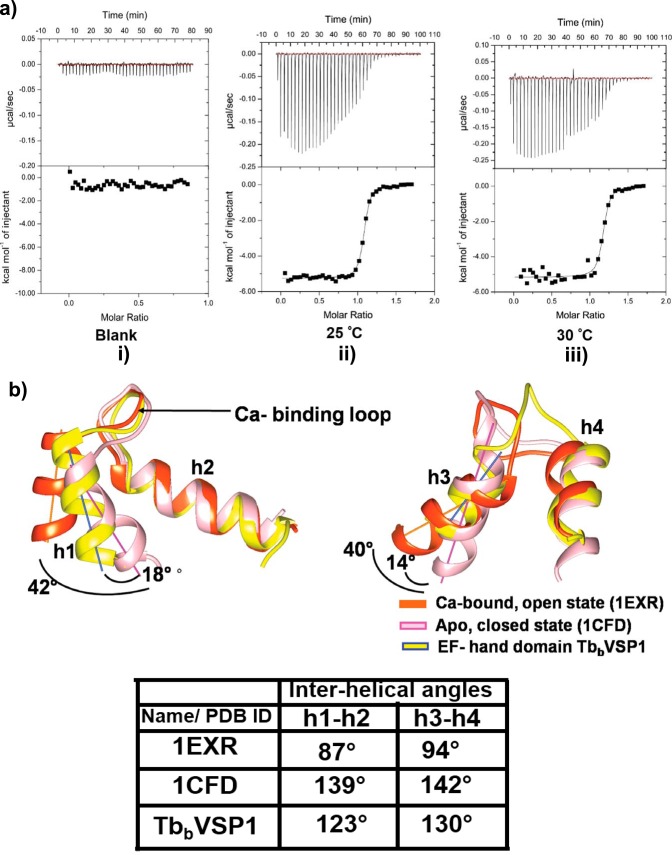

Ca+2 Binding Affinity of EF Hand Domain

We investigated whether EF hand domain is a functional Ca+2 binder. We deployed ITC to determine Ca+2 binding and measure binding affinities along with thermodynamic parameters. Because PPase domains have divalent cation binding capabilities, we generated a protein encompassing 1–160 residues that contains the EF hand domain. Initial titration of Ca+2 in HEPES buffer against 50 μm protein showed a sharp transition in ITC curves, indicating high affinity interaction. The results presented in Fig. 8a show good fit to a simple one-site model, describing specific binding driven by both favorable enthalpy and entropy changes. As in Table 3, binding affinity of EF hand domain is in nanomolar range (Kd = ∼65 nm at 25 °C), and this affinity decreases slightly upon increase in temperature, which is again accompanied by favorable changes in heat and entropy. Note that the structure of EF hand domain presented in this work is in Ca+2-free form. Comparison of EF hand domain with an archetypal Ca+2 binding protein calmodulin (PDB ID 1EXR; Ca+2-bound form and 1CFD in unbound form) revealed that the putative Ca+2 binding loop which connects the helices h1 and h2 in EF hand domain adopts a conformation similar to Ca+2-bound form of calmodulin (Fig. 8b, left panel). Further, measurement of interhelical angles and angular displacement of helices shows that the EF hand domain is in a partially open state, deviating from geometry proposed for a closed state (Ref. 43 and Fig. 8b, bottom panel). Finally, the loop connecting helices h3 and h4 shows poor overlap with either Ca+2-bound or unbound forms (Fig. 8b, right panel).

FIGURE 8.

Calcium binding by EF hand domain and interhelical angles. a, representative ITC titrations. The upper panel shows heat flows observed during the experiment; the lower panel shows integrated heats of each Ca+2 injection; lines show fit of data to the binding model describing ligand interaction with a single binding site. Panel i, buffer Ca+2 titrations showing heat of dilutions. Panels ii and iii, EF hand domain Ca+2 titration in 50 mm Na-HEPES and 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.2, at 25 °C (panel ii) and 30 °C (panel iii). b, structural superposition of EF hand domain and calmodulin showing differences in interhelical packing between helices h1 and h2 (left panel) and helices h3 and h4 (right). Left panel shows helix h1 of TbbVSP1 (yellow) and calcium bound calmodulin (orange) are bent by 18° and 42°, respectively, relative to closed state (pink). Whereas, the right panel shows helices h3 are bent by 14° and 40° relative to closed state. PDB codes of calcium bound and unbound forms calmodulin are mentioned in parentheses. Interhelical angles (bottom) are shown in a tabular form.

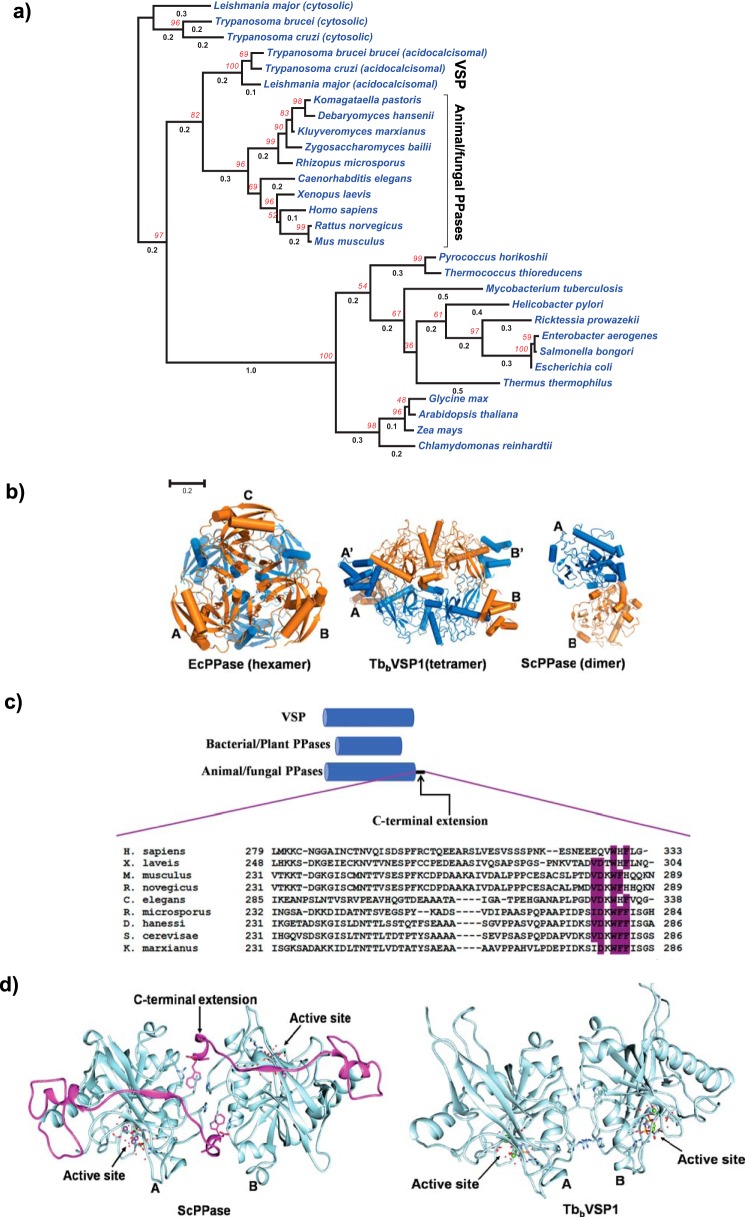

Comparison TbbVSP1 Structure with Other PPases

A sequence-based phylogenetic tree construction supports the notion that TbbVSP1 is a class I PPase because it clusters with animal/fungal class I PPases. However, the branch length of animal/fungal PPase clade tends to be longer than acidocalcisomal VSPs, suggesting a more rapid rate of evolution (Fig. 9a). A survey of crystal structures of class I PPases in the PDB reveals that TbbVSP1 architecture presented in this study represents an atypical class I PPase, not only in terms of its domains but also its oligomer state (Fig. 9a). The PPase domain structure of TbbVSP1 is similar to yeast PPase (rmsd 0.6 Å for 202 Cα atoms). A notable difference is the presence of a longer loop in TbbVSP1, which results from insertion of 11 amino acids (residues 208–218). This loop contributes to tetramer stability by burying 400 Å2 of accessible area at interface I. Another notable difference is an auxiliary space proximal to PPi binding, which is absent in yeast PPase. We find that this structural difference translates to residue Gly374 of TbbVSP1 PPase domain. The corresponding structurally equivalent residue in yeast PPase is Lys198, which points toward the active site and thus occludes the space formation near the PPi binding site. Again, Gly374 is highly conserved among kinetoplastid VSPs. However, the most striking difference is the absence of C-terminal extension from TbbVSP1 PPase domain (Fig. 9c). This C-terminal extension is also absent from bacterial and plant PPases (Fig. 9c). Superposition of yeast PPase dimer as a whole to dimer component of TbbVSP1 (PPase domains only) gives a very high rmsd value of ∼4 Å, indicating that spatial arrangement of monomers forming the primary dimer interface in TbbVSP1 is different from yeast PPase (Fig. 9d). This difference can also be judged by examining the orientation of catalytic center in each monomer of yeast and TbbVSP1; in the former, they are arranged on opposite faces, whereas in TbbVSP1, they consort in a sideways manner (Fig. 9d). Overlay of aforementioned dimers also reveals a notable difference in their packing angles, which entails a rotational shift of 20° in TbbVSP1 monomer with respect to yeast PPase monomer; this rotational shift is accompanied by translation of 101 Å. The dimer interface of yeast PPase (total buried area, ∼1920 Å2) is also more substantial than TbbVSP1 (∼1650 Å2). This may be explained by the fact that C-terminal extension of yeast PPase contributes significantly (∼43% total buried surface) to dimerization interface of yeast PPase. Further, theoretical free energy of dissociation from PISA indicates that C-terminal is important for stability of the yeast PPase dimer. Therefore, C-terminal extensions of yeast/animal PPases might act as clamps holding monomers, and their absence in TbbVSP1 might increase the fluidity of dimer interface region, resulting in different spatial arrangement.

FIGURE 9.

Comparison of crystal structures/biological assemblies and phylogeny. a, maximum likelihood tree based on protein sequences of soluble PPase domains. Boot strap values from 500 iterations are shown in red font, and branch lengths are shown in black font. The 0.2 bar represents amino acid substitution per site. Putative cytosolic PPases of kinetoplastid are used as the out group. b, biological assemblies of TbbVSP1 and PPases from E. coli and S. cerevisiae. c, schematic shows the C-terminal extension present in animal/fungal PPases. Residues that contribute to dimer interface of yeast PPase are conserved and highlighted in purple/magenta in the sequence alignment. d, ribbon cartoon of PPase domain of yeast and TbbVSP1 showing different spatial arrangement of monomers, which is also indicated by topology of active site in each dimer. The C-terminal extension of ScPPase colored in magenta.

Discussion

TbbVSP1 has a bidomain architecture consisting of the EF hand domain and the PPase domain. Although most known class I PPases are single domain proteins that form hexameric/dimeric assemblies, TbbVSP1 is distinct in being tetrameric. Aside from TbbVSP1 crystal structure, SAXS and EM confirm the unprecedented tetrameric assembly of TbbVSP1. Although crystal structure analysis indicates a static tetrameric arrangement, our SAXS data hint at a rather dynamic assembly in solution. Together, the SAXS modeling and crystal structure suggest that the flexibility manifests itself via hinge motion in EF hand domains, although the functional implication of flexibility remains unclear. This is also a nice example where “in solution” and “in crystallo” structural techniques together are more informative than either alone.

Although structurally intriguing, biochemically the TbbVSP1 is similar to TbgVSP1. Both substrate specificity profile and active site structure strongly indicate that PPi is a physiological substrate for TbbVSP1; however, PPase activity is optimal at alkaline pH range only, indicating that PPi may not hydrolyzed constitutively by TbbVSP1 in acidocalcisomes. However, depending on identity of the co-factor, catalytic capabilities of TbbVSP1 expand beyond PPi, resulting in hydrolysis of poyP3 over a range of pH, both acidic and neutral. This suggests a regulatory role for TbbVSP1 in acidocalcisome, which is rich in polyphosphates. In this context, Lemercier et al. (17) have previously suggested that to prevent polyP3 accumulation in the cell compartment where polyP hydrolysis is occurring, polyP3 is further hydrolyzed by VSP1 in the presence of Zn+2 at an acidic pH. That followed by an increase in pH and release of Ca+2, H+ ions by VSP1 and exopolyphosphatase could drive the reaction forward producing Pi and PPi within acidcocalcisome (17). Furthermore, acidocalcisomes seem active in several biological processes after alkalization, which also involves hydrolysis of polyphosphates to short chain phosphates and pyrophosphates (44, 45). This may well provide the basis for biological activity of TbbVSP1.

Our ITC data show that the EF hand domain of TbbVSP1 is a functional and specific Ca+2 ion binder. Surprisingly, TbbVSP1 structure reveals a conformation similar to an open or Ca+2-bound state, despite absence of metal bound in the putative binding site (Fig. 8b). Inspection of the TbbVSP1 tetramer structure reveals that conformation of calcium binding loops is stabilized by electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions with a symmetry-related molecule (Interface II; Fig. 3c). Thus, crystal forces might partially mimic a Ca+2 atom, stabilizing an apparent “open” conformation. However, this remains to be verified using crystals in which TbbVSP1 is packed in alternate forms.

We also observed that Ca+2 is able to inhibit both full-length TbbVSP1 and Δ166 TbbVSP1 alike (IC50 = ∼50 μm in presence 3 mm Mg+2) (Fig. 7c), suggesting that EF hand binding to Ca+2 does not play a role in inhibition of PPi hydrolysis; this was also observed previously for TbgVSP1 (17). Instead, the Ca+2-PPi complex acts a competitive inhibitor of Mg+2-PPi complex, inhibiting PPase activity by a mechanism suggested previously (46). Furthermore, EF hand domain deletion also has no effect on either PPi or polyP3 hydrolysis by TbbVSP1. In this context, the crystal structure of TbbVSP1 presented in this study indicates that relative positions of EF hand domain in TbbVSP1 monomer, dimeric, or tetrameric states disallow role for EF hand in direct interactions with substrate or co-factor metal binding site (in the PPase domain). This hence explains the inertness of the EF hand domain toward TbbVSP1 enzyme activity, and this explanation may also hold true for TbgVSP1, although spatial arrangement of EF hand and PPase domains in this assembly will vary, because the protein is reportedly hexameric (17).

A comparison between class I eukaryotic (animal/fungal) PPase family and TbbVSP1 suggests an intriguing evolutionary variety from dimeric to tetrameric states. On the basis of structural and phylogenetic data, a possible scenario emerges in which C-terminal extension has been acquired by animal/fungal PPases, independently after divergence from a protein that formed the last common ancestor between animal/fungal and VSPs. From atomic resolution crystal structures of yeast PPase and TbbVSP1, it is apparent that the C-terminal extension holds PPase domains like a clamp, thus resulting in a stable dimeric state. From the structural data so far, it seems that prokaryotic/archaeal and plant class I PPases also lack this typical C-terminal extension and interestingly show higher or non dimeric oligomerization state (trimers and hexamers). It might also be intriguing to suggest that the absence of such an extension in TbbVSP1 leads to a different packing arrangement of PPase domains in primary dimers, which is amenable to tetramer formation. Indeed, studies in past have shown that loss or addition of certain sequences or structural elements can result in spatial reorientation of subunits that can induce different oligomeric states (47, 48).

In conclusion, our study presents an unprecedented structural assembly of the EF hand and the PPase domain within one TbbVSP1. This work provides a structural foundation both for mechanistic exploration of TbbVSP1 and for scoring feasibility of small molecule inhibitor development in future.

Author Contributions

A. S. and A. J. conceived the study. A. J. performed purification of the enzyme, biochemical assays, ITC, determined and analyzed the x-ray structure. M. Y. and H. B. collected x-ray data. A. R. R. performed and analyzed SAXS experiments. L. B. and C. V.-B. conducted TEM studies. The manuscript was written primarily by A. S. and A. J., but all authors contributed.

Acknowledgment

We express deep gratitude to V. K. Aves for constant encouragement.

This work was supported by Outstanding Scientist Research Programme Grants PR6303 (to A. S.) and PR3084 (to A. S. and M. Y.) from the Department of Biotechnology of the Government of India. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 5C5V) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

A. Jamwal, A. R. Round, L. Bannwarth, C. V. Bryan, H. Belrhali, M. Yogavel, and A. Sharma, unpublished observations.

- PPase

- inorganic pyrophosphatase

- VSP

- vacuolar soluble protein

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy

- ITC

- isothermal calorimetry

- rmsd

- root mean square deviation

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- polyP3

- tripolyphosphate.

References

- 1.Brun R., Blum J., Chappuis F., and Burri C. (2010) Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet 375, 148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez P. J., Molyneux D. H., Fenwick A., Kumaresan J., Sachs S. E., Sachs J. D., and Savioli L. (2007) Control of neglected tropical diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 357, 1018–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keita M., Bouteille B., Enanga B., Vallat J. M., and Dumas M. (1997) Trypanosoma brucei brucei: a long-term model of human African trypanosomiasis in mice, meningo-encephalitis, astrocytosis, and neurological disorders. Exp. Parasitol. 85, 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirchhoff L. V., Bacchi C. J., Wittner M., and Tanowitz H. B. (2000) African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2, 66–69 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy P. G. (2004) Human African trypanosomiasis of the CNS: current issues and challenges. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 496–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Docampo R., and Moreno S. N. (2003) Current chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitol. Res. 90, S10–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornberg A. (1962) On metabolic significance of phosphoroylytic and pyrophosphorolytic reactions. In Horizons in Biochemistry, pp. 251–264, Academic Press, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J., Brevet A., Fromant M., Lévêque F., Schmitter J. M., Blanquet S., and Plateau P. (1990) Pyrophosphatase is essential for growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172, 5686–5689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundin M., Baltscheffsky H., and Ronne H. (1991) Yeast PPA2 gene encodes a mitochondrial inorganic pyrophosphatase that is essential for mitochondrial function. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 12168–12172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shintani T., Uchiumi T., Yonezawa T., Salminen A., Baykov A. A., Lahti R., and Hachimori A. (1998) Cloning and expression of a unique inorganic pyrophosphatase from Bacillus subtilis: evidence for a new family of enzymes. FEBS Lett. 439, 263–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tammenkoski M., Benini S., Magretova N. N., Baykov A. A., and Lahti R. (2005) An unusual, His-dependent family I pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41819–41826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabrichniy I. P., Lehtiö L., Tammenkoski M., Zyryanov A. B., Oksanen E., Baykov A. A., Lahti R., and Goldman A. (2007) A trimetal site and substrate distortion in a family II inorganic pyrophosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1422–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooperman B. S., Baykov A. A., and Lahti R. (1992) Evolutionary conservation of the active site of soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17, 262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer W., Moll R., Kath T., and Schäfer G. (1995) Purification, cloning, and sequencing of archaebacterial pyrophosphatase from the extreme thermoacidophile Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 319, 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young T. W., Kuhn N. J., Wadeson A., Ward S., Burges D., and Cooke G. D. (1998) Bacillus subtilis ORF yybQ encodes a manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase with distinctive properties: the first of a new class of soluble pyrophosphatase? Microbiology 144, 2563–2571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Docampo R., de Souza W., Miranda K., Rohloff P., and Moreno S. N. (2005) Acidocalcisomes: conserved from bacteria to man. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemercier G., Espiau B., Ruiz F. A., Vieira M., Luo S., Baltz T., Docampo R., and Bakalara N. (2004) A pyrophosphatase regulating polyphosphate metabolism in acidocalcisomes is essential for Trypanosoma brucei virulence in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3420–3425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espiau B., Lemercier G., Ambit A., Bringaud F., Merlin G., Baltz T., and Bakalara N. (2006) A soluble pyrophosphatase, a key enzyme for polyphosphate metabolism in Leishmania. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1516–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galizzi M., Bustamante J. M., Fang J., Miranda K., Soares Medeiros L. C., Tarleton R. L., and Docampo R. (2013) Evidence for the role of vacuolar soluble pyrophosphatase and inorganic polyphosphate in Trypanosoma cruzi persistence. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 699–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Docampo R., and Moreno S. N. (2008) The acidocalcisome as a target for chemotherapeutic agents in protozoan parasites. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 882–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotsikorou E., Song Y., Chan J. M., Faelens S., Tovian Z., Broderick E., Bakalara N., Docampo R., and Oldfield E. (2005) Bisphosphonate inhibition of the exopolyphosphatase activity of the Trypanosoma brucei soluble vacuolar pyrophosphatase. J. Med. Chem. 48, 6128–6139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Voorhis W. C., Hol W. G., Myler P. J., and Stewart L. J. (2009) The role of medical structural genomics in discovering new drugs for infectious diseases. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otowinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., and Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwilliger T. C., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Afonine P. V., Moriarty N. W., Zwart P. H., Hung L. W., Read R. J., and Adams P. D. (2008) Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 61–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pernot P., Round A., Barrett R., De Maria Antolinos A., Gobbo A., Gordon E., Huet J., Kieffer J., Lentini M., Mattenet M., Morawe C., Mueller-Dieckmann C., Ohlsson S., Schmid W., Surr J., Theveneau P., Zerrad L., and McSweeney S. (2013) Upgraded ESRF BM29 Beamline for SAXS on macromolecules in solution. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 20, 660–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Maria Antolinos A., Pernot P., Brennich M. E., Kieffer J., Bowler M. W., Delageniere S., Ohlsson S., Malbet Monaco S., Ashton A., Franke D., Svergun D., McSweeney S., Gordon E., and Round A. (2015) ISPyB for BioSAXS, the gateway to user autonomy in solution scattering experiments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 71, 76–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Shkumatov A. V., Tria G., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H. J., and Svergun D. I. (2012) PRIMUS, a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petoukhov M. V., Franke D., Shkumatov A. V., Tria G., Kikhney A. G., Gajda M., Gorba C., Mertens H. D., Konarev P. V., and Svergun D. I. (2012) New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 45, 342–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svergun D. I. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franke D., and Svergun D. I. (2009) DAMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 342–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volkov V. V., and Svergun D. I. (2003) Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 860–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tria G., Mertens H. D., Kachala M., and Svergun D. I. (2015) Advanced ensemble modelling of flexible macromolecules using x-ray solution scattering. IUCrJ. 2, 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludtke S. J. (2010) 3-D structures of macromolecules using single-particle analysis in EMAN. Methods Mol. Biol. 673, 157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank J., Radermacher M., Penczek P., Zhu J., Li Y., Ladjadj M., and Leith A. (1996) SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heikinheimo P., Lehtonen J., Baykov A., Lahti R., Cooperman B. S., and Goldman A. (1996) The structural basis for pyrophosphatase catalysis. Structure 4, 1491–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baykov A. A., Evtushenko O. A., and Avaeva S. M. (1988) A malachite green procedure for orthophosphate determination and its use in alkaline phosphatase-based enzyme immunoassay. Anal. Biochem. 171, 266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Permyakov E. A. (2009) Metalloproteomics, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zyryanov A. B., Shestakov A. S., Lahti R., and Baykov A. A. (2002) Mechanism by which metal cofactors control substrate specificity in pyrophosphatase. Biochem. J. 367, 901–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng H., Chordia M. D., Cooper D. R., Chruszcz M., Müller P., Sheldrick G. M., and Minor W. (2014) Validation of metal-binding sites in macromolecular structures with the CheckMyMetal web server. Nat. Protoc. 9, 156–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gifford J. L., Walsh M. P., and Vogel H. J. (2007) Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 405, 199–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz F. A., Rodrigues C. O., and Docampo R. (2001) Rapid changes in polyphosphate content within acidocalcisomes in response to cell growth, differentiation, and environmental stress in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26114–26121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemercier G., Dutoya S., Luo S., Ruiz F. A., Rodrigues C. O., Baltz T., Docampo R., and Bakalara N. (2002) A vacuolar-type H+-pyrophosphatase governs maintenance of functional acidocalcisomes and growth of the insect and mammalian forms of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37369–37376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samygina V. R., Popov A. N., Rodina E. V., Vorobyeva N. N., Lamzin V. S., Polyakov K. M., Kurilova S. A., Nazarova T. I., and Avaeva S. M. (2001) The structures of Escherichia coli inorganic pyrophosphatase complexed with Ca2+ or CaPPi at atomic resolution and their mechanistic implications. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 633–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joerger A. C., Rajagopalan S., Natan E., Veprintsev D. B., Robinson C. V., and Fersht A. R. (2009) Structural evolution of p53, p63, and p73: implication for heterotetramer formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17705–17710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baden E. M., Owen B. A., Peterson F. C., Volkman B. F., Ramirez-Alvarado M., and Thompson J. R. (2008) Altered dimer interface decreases stability in an amyloidogenic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15853–15860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]