STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Objective

We aimed to create decision aids (DAs) for patients considering destination therapy left ventricular assist device (DT LVAD).

Background

DT LVAD is a major decision for patients with end-stage heart failure. Patients facing decisions with complex tradeoffs may benefit from high-quality decision support resources.

Methods

Following the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) guidelines and based on a needs assessment with stakeholders, we developed drafts of paper and video DAs. With input from patients, caregivers, and clinicians through alpha testing, we iteratively modified the DAs to ensure acceptability.

Results

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 24 patients, 20 caregivers, and 24 clinicians to assess readability, bias, and usability of the DAs. Stakeholder feedback allowed us to integrate aspects critical to decision-making around highly invasive therapies for life-threatening diseases, including addressing emotion and fear of death, using gain frames for all options that focus on living, highlighting palliative and hospice care, integrating the caregiver role, and utilizing a range of balanced testimonials. After 19 iterative versions of the paper DA and four versions of the video DA, final materials were made available for wider use.

Conclusion

We developed the first IPDAS-level DAs for DT LVAD. Given the extreme nature of this medical decision, we augmented traditional DA characteristics with non-traditional DA features to address a spectrum of cognitive, automatic, and emotional aspects of end-of-life decision-making. Not only are the DAs important tools for those confronting end-stage heart failure, but the lessons learned will likely inform decision support for other invasive therapies.

UNSTRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Destination therapy left ventricular assist device (DT LVAD) is a major decision for patients with end-stage heart failure. We aimed to create decision aids (DAs) to support patients and their caregivers considering DT LVAD. After developing initial drafts of paper and video DAs, we conducted alpha testing through interviews with 24 patients, 20 caregivers, and 24 clinicians and iteratively modified the DAs. This allowed us to integrate aspects critical to decision-making around highly invasive therapies for life-threatening diseases and to augment traditional DA characteristics with non-traditional DA features to attend to a spectrum of cognitive, automatic, and emotional aspects.

Keywords: destination therapy, heart-assist devices, heart failure, shared decision-making, decision aid, patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

With medicine’s expanding array of life-prolonging technologies, older and sicker people are increasingly offered invasive interventions. One such therapy, the left ventricular assist device (LVAD), is offered to people dying from end-stage heart failure who are ineligible for heart transplant. These patients may choose to live out the remainder of their lives dependent on a partial artificial heart – so called “destination therapy” (DT). The DT LVAD is a stark example of the difficult decisions created by new technologies for people with end-stage illness. For eligible patients who decide not to get a DT LVAD, 2-year survival is less than 10%; with a DT LVAD, 2-year survival is approximately 70% (1). However, significant risks accompany a DT LVAD, including stroke, serious infection, severe bleeding, and reoperation; chronic conditions that make patients transplant ineligible persist; and significant lifestyle changes occur, including the need for patients to be connected to electricity at all times (1,2). Further, many implanting programs require formal commitment from a proposed caregiver as part of eligibility, placing substantial responsibility on a family member or friend (3).

Given these complex tradeoffs, shared decision-making – guided by standardized methods and materials to support the decision process – has been encouraged by several organizations (4) and is supported by a large body of literature (5,6). Unfortunately, patients, caregivers, and clinicians have had suboptimal guidance and support for DT LVAD decision-making: existing informed consents are written at a high reading comprehension level, while industry materials are optimistically biased, contain outdated statistics, and fail to adequately discuss risks (7). These industry materials are widely used among LVAD centers (8). While the ethical mandate surrounding informed consent is clear (9), achieving true informed consent in this setting is challenging when using consent forms and industry materials alone (4).

Decision aids (DAs) have emerged as an effective intervention to improve patients’ decision-making (5). The International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) collaboration has released several guidelines and standards on both how to develop DAs and how to ensure they are of quality (10,11). Many DAs have been developed and studied in randomized trials. However, only a small minority are related to decisions faced by people with advanced illness, and end-of-life decisions were specifically excluded from the Cochrane review of DAs (6). Currently, no widely available DT LVAD informational materials meet criteria for a patient DA (7), and no standard education and consent processes exist across different hospitals and LVAD programs (8).

We aimed to develop novel DAs for patients offered DT LVAD. In order to first understand stakeholders’ decisional needs, a needs assessment was performed with patients, caregivers, and mechanical circulatory support (MCS) coordinators (8,12,13), which revealed several important findings: 1) the decision-making process is highly emotional and often dominated by fear of death; 2) these emotions and the high-stakes nature of the clinical circumstances create a situation where many patients do not cognitively engage declination of DT LVAD as an option, instead focusing on doing “anything it takes”; 3) caregivers are deeply involved in the decision-making process and subsequent care of the patient and often feel a tension between gratitude and burden; 4) caregivers often project personal desires onto patients’ decision-making, with many feeling a tension between wanting to be involved while also wanting to support the patients’ decisions; 5) MCS coordinators desire an iterative, multi-disciplinary approach to DT LVAD education; and 6) coordinators feel a tension between wanting to explain all aspects of DT LVAD to patients and not wanting to overwhelm or “scare” them away from the device.

Guided by IPDAS and the needs assessment, and also attending to the unique nature of the DT LVAD decision process, we developed two novel DT LVAD DAs for patients and their caregivers. Herein, we describe the methods of development and provide illustrative examples of important aspects of our DAs.

METHODS

Development Team

The core development team consisted of an advanced heart failure cardiologist, a geriatric and palliative medicine physician, a nurse practitioner specializing in the care of patients with LVADs, and a health communication specialist. All aspects of the study received approval from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and written or verbal informed consent was obtained from patient and caregiver participants.

Framework

DA development was guided by 1) the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (14), which dictated we complete preliminary assessments to understand stakeholders’ decisional needs as a foundation for DA development; and 2) IPDAS, which provided a model for systematic DA development and evidence-based criteria to ensure our DAs were of quality (10,11). Additionally, we further explored domains identified as important during the framework-guided needs assessment, as detailed in the introduction (8,12,13).

Alpha Testing

Overview of the Development Process

Following the IPDAS development process, we completed an environmental scan to ensure the need for a DT LVAD DA existed (7), conducted a systematic review of the literature to ensure all data in the DAs were accurate and current (1), and completed the needs assessment of relevant stakeholders. Since patients considering DT LVAD are often very ill, we chose two DA formats easily implementable into an intensive care unit setting: 1) a “paper” version (fixed-page format) accessible online for use within the clinical encounter; and 2) a video version containing clinician-narrated information and balanced patient and caregiver testimonials.

Informed by efficiencies experienced during prior development of a DA for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (15), we first iteratively developed content on paper, where making frequent edits was most practical. Once satisfied with a draft, we followed the IPDAS development process and performed in-depth qualitative interviews about the DAs with patients, caregivers, and clinicians for alpha testing, with subsequent serial edits to reflect their feedback. After every two to three interviews, we met to discuss participants’ feedback and recommendations, then came to a team consensus on which changes to include. This process continued until no new ideas emerged during interviews. Near the end of the process, a graphic designer created a high-quality version of the paper DA. Simple Measure of Gobbledygook and Fry readability tests were conducted to ensure readability. Nineteen updated versions were created throughout development.

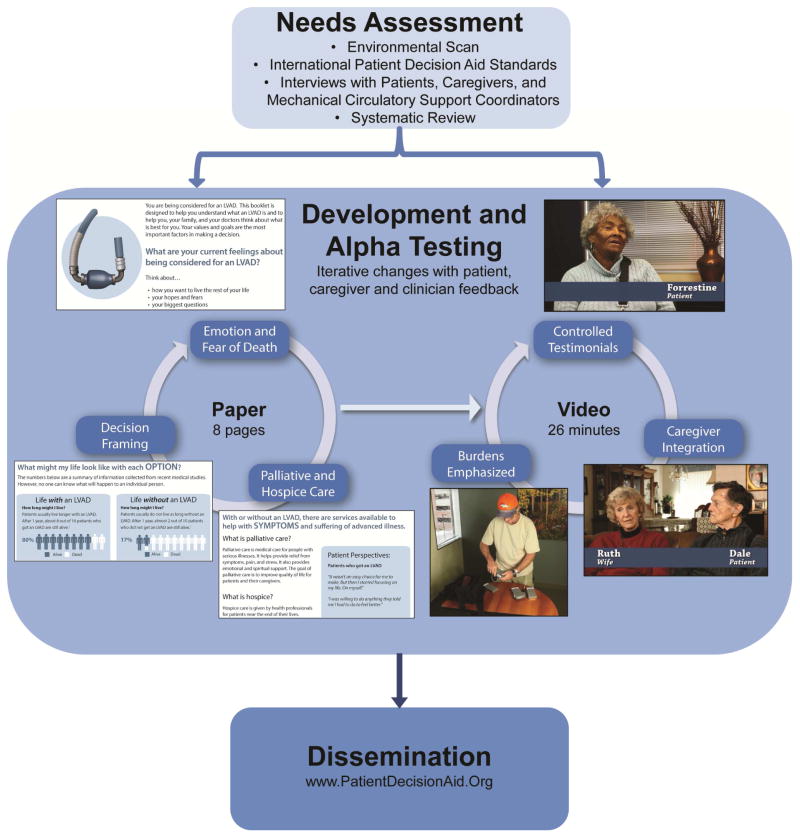

As the paper DA neared a final version, development of the video DA was initiated. The video script was drafted from the paper version and internally updated several times. A prototype version of the video was created. The alpha testing for the video occurred in the same way as the paper DA, with re-filming and four updated versions created throughout the process. See Figure 1 for overview.

Figure 1. Project Overview.

Summary of the methods and main results of the paper.

Patient and Caregiver Interviews

Patient and caregiver participants were recruited from the University of Colorado Hospital. The health communication specialist recruited and interviewed all participants. Interviews were conducted sequentially during the iterative development process; therefore, participants viewed different versions of the DAs as they evolved. Participants were interviewed either in-person or over the phone with a semi-structured interview guide based on the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. The guide asked about the participants’ own decision-making experience and whether the DA met their decision needs, including the following domains: 1) questions on the length, graphics, understandability, and balance of the DA (16); 2) assessment of their feelings and opinions about the content of the DA; and 3) solicitation of recommendations for improvement.

Early versions of the DAs were shown to patients living with an LVAD, patients who had declined an LVAD, current and bereaved caregivers of patients who had accepted or declined an LVAD, and patients with heart failure who were not yet eligible for an LVAD and their caregivers. The near-final versions were tested with patients and caregivers actively undergoing the decision process, the setting in which the DAs were designed to be used.

Clinician Interviews

Members of the development team conducted in-person interviews with local specialists in cardiology, advanced heart failure, and palliative care to ensure the DAs would be acceptable in real world practice. Additional nationwide feedback was solicited in-person, over the telephone, and through e-mail from MCS coordinators, cardiologists, palliative care specialists, nurses, and social psychologists.

RESULTS

A total of 24 patients and 20 caregivers were interviewed. All but four patient and caregiver interviews were conducted in person, lasting a median of 37 minutes. Clinician feedback came from local cardiology and palliative care groups, as well as 24 external clinicians from 16 medical centers across the United States. Demographic information for participants is provided in Table 1. In addition to following IPDAS criteria (see “Final Version” below for details), we took a deeper and nuanced approach to certain developmental aspects deemed particularly important to this clinical situation, as detailed below and in Table 2.

Table 1.

Alpha testing participant characteristics

| Patient (n=24) | Caregiver (n=20) | Clinician (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 65 (29–84) | 65 (47–80) | - |

| Gender, female | 3 | 17 | 9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 19 | 19 | - |

| Black | 3 | 1 | - |

| Asian | 1 | 0 | - |

| Native American | 1 | 0 | - |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 2 | 1 | - |

| High school graduate or GED | 6 | 4 | - |

| Some college | 7 | 7 | - |

| College graduate | 4 | 3 | - |

| Any post-graduate work | 1 | 2 | - |

| Unknown | 4 | 3 | - |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 17 | 16 | - |

| Divorced | 4 | 0 | - |

| Widowed | 1 | 2 | - |

| Never married | 2 | 0 | - |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 | |

| Patient indication | |||

| DT LVAD | 6 | 5 | - |

| BTT LVAD | 2 | 2 | - |

| DT LVAD decliner | 1 | 1 | - |

| Heart failure, no LVAD offered | 5 | 1 | - |

| Heart failure, considering LVAD | 10 | 11 | - |

| Years since offered LVAD | |||

| >1 year | 6 | - | - |

| <1 year | 13 | - | - |

| N/A, no LVAD | 5 | - | - |

| Type of LVAD pump | |||

| HeartMate II | 6 | - | - |

| HVAD | 2 | - | - |

| N/A, no LVAD | 16 | - | - |

| INTERMACS profile, heart failure patients considering LVAD | |||

| INTERMACS 1 | 1 | - | - |

| INTERMACS 2 | 2 | - | - |

| INTERMACS 3 | 2 | - | - |

| INTERMACS 4 | 3 | - | - |

| INTERMACS 5 | 2 | - | - |

| N/A, LVAD or not yet LVAD eligible | 14 | - | - |

| Caregiver status | |||

| Current | - | 18 | - |

| Bereaved | - | 2 | - |

| Caregiver relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse | - | 13 | - |

| Mother | - | 2 | - |

| Sister | - | 2 | - |

| Child | - | 2 | - |

| In-law | - | 1 | - |

| Professional Title | |||

| Cardiologist | - | - | 11 |

| Palliative care specialist | - | - | 4 |

| MCS coordinator | - | - | 5 |

| Social psychologist | - | - | 1 |

| General internist | - | - | 1 |

| Clinical psychologist | - | - | 1 |

| Other | - | - | 1 |

BTT, bridge-to-transplant; DT, destination therapy; INTERMACS, Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MCS, mechanical circulatory support

Table 2.

Important developmental aspects of the DT LVAD decision aids and alpha testing responses

| Important Developmental Aspect | Direct Excerpts from DA | Why Aspect Was Used | Alpha Testing Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility in use | “You are being considered for DT LVAD”; “…if your doctors feel you are eligible…” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; alpha testing | Nearly all patient and caregivers expressed desire for earlier education; clinicians wanted DAs to be used in multiple settings. Length and format of DAs was made suitable for both a clinical setting and as a take-home resource. |

| Emotion and heuristics | “What are your current feelings about being considered for an LVAD?”; “Many patients like you have found this scary or confusing. Some patients have felt pressured to make a decision. These emotions are normal.” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; alpha testing | Interviews confirmed that mechanisms for acknowledging and addressing emotion were desired by patients and caregivers. Many participants reported an appreciation for the language and reminders throughout. |

| Fear of death | “Whether we like it or not, everybody eventually dies.” “We don’t want to die, you know, the first reaction is, I’ll do whatever it takes to live, and then coming to grips with the fact that we all die at some point…” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; alpha testing | Many participants expressed that direct language in the DAs served as an important reminder for patients and caregivers going through the decision. Several caregivers commented on how crucial this acknowledgement is during decision making. |

| Tone and balance | “Think about how you hope to live the rest of your life.” “You have some control over how you will live the rest of your life.” “The right choice really depends on how you hope to live the rest of your life.” “Life with an LVAD” and “Life without an LVAD” | Alpha testing | Initially, several patients and caregivers thought the DA was too negative toward the LVAD and made it seem “overwhelming” or “burdensome,” but many of these same participants also appreciated the realistic, “blunt” depiction. Some clinicians acknowledged how language around death and complications was necessary to convey the seriousness of the choice, while the majority of cardiologists considered initial versions of the DA to be overly in favor of LVAD, failing to convey the gravity of the decision. Final versions of the DAs with updated tone were deemed satisfactory by most participants. |

| Decision framing when both options have high morbidity and mortality | “Some patients choose to get an LVAD. Other patients decide not to get an LVAD. The right choice really depends on how you hope to live the rest of your life.” | IPDAS; patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; alpha testing | Most participants commented on how balanced the presentation of both options was, and they appreciated the visual comparison. Some participants commented that the declining option should have more complications presented. Since death is imminent for the majority who choose this option, we elected to highlight what life would look like without an LVAD in comparison to potential complications of life with an LVAD. |

| Turning complex data into a meaningful summary | “Patients usually live longer with an LVAD. After 1 year, about 8 out of 10 patients who get an LVAD are still alive.” “Patients usually do not live as long without an LVAD. After 1 year, almost 2 out of 10 patients who did not get an LVAD are still alive.” “The numbers below are a summary of information collected from recent medical studies. However, no one can know what will happen to an individual person.” “While no one can predict the future, understanding what could happen may help you to feel more at peace about your decision.” | IPDAS; patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; systematic review | The final summary of outcomes was favorable to all participant groups – the data presented was deemed detailed enough, understandable and digestible, and a good representation of the overall picture of what life would look like with each option. Clinicians, in particular, appreciated the use of uncertainty in the DAs. |

| Burdens emphasized | “If I get an LVAD, how will my life change?” “There are many life-changing aspects of the LVAD that you should consider.” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; alpha testing | Overall, this portion of the DAs was deemed the “most important” or “favorite” part by patient and caregiver participants. Participants were particularly drawn to the visual portion of the videos and stated it was more helpful than simply hearing an explanation. |

| Palliative and hospice care | “With or without an LVAD, there are services available to help with symptoms and suffering of advanced illness.” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; alpha testing | Highlighting these resources was a new and unexpected aspect for most of the patient and caregiver participants. Many felt it was important information, and clinicians appreciated the inclusion of these resources. Upon initial viewing of the DA, some patients were intimidated or unsure about the discussion of hospice; however, after viewing the information, all agreed it was helpful. |

| Caregiver integration | “An LVAD is a major decision for caregivers, too.” “When a patient gets an LVAD, the caregiver’s lifestyle can change further.” | Patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; alpha testing | Some participants felt the caregiver information should be provided in a separate DA; however, most agreed it was helpful to have the patient and caregiver information intermixed so that each could see what was expected of the other. All participants agreed that caregiver information was necessary. |

| Use of explicit and implicit values clarification and controlled Testimonials | “Think about how you want to live the rest of your life, your hopes and fears, your biggest questions.” “Your values and goals are the most important factors in making a decision.” “What do you hope for with or without an LVAD? What frightens you about living with or without an LVAD?” “I was willing to do anything they told me I had to do to feel better” and “I don’t know if the pump would keep me alive. And even if it does, I’m not sure it would be worth living. Because I’m not going to claw and hold on to the wall to stay alive.” | IPDAS; patient, caregiver and clinician needs assessments; environmental scan; alpha testing | Nearly all of the participants stated they liked the values clarification exercises, and many took time to complete the written activities on the paper DA. The response to the testimonials was overwhelmingly positive among all participant groups. Participants reported the testimonials presented a variety of experiences with the decision-making process and life with or without an LVAD, and they appreciated the balanced presentation of outcomes. In the first version of the DA, the wife of a decliner was included; however, many participants reported a desire to see the decliner patient perspective directly. For version two of the video, we were able to include a patient who declined DT LVAD. |

DA, decision aid; DT, destination therapy; IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aid Standards; LVAD, left ventricular assist device

Flexibility in Use

Participant feedback highlighted the desire for DA availability early on in disease progression, while also being tailored to those currently facing the decision. The DAs were thus created for multiple settings and states of disease progression; they were designed for both outpatient early education and inpatient decision-making.

A key consideration in DA development was how to address different indications for LVAD: DT, bridge-to-transplantation, and bridge-to-decision. Although the same device can often be used for multiple indications and patients can change from one indication to another, we ultimately found that DT-specific DAs were optimal because: 1) the DT perspective is focused on living the remainder of life with the LVAD whereas the bridge-to-transplantation perspective is often forward-looking to transplantation; 2) DT is the largest and fastest growing indication for an LVAD; and 3) adequately supporting the full range of MCS decision-making in one tool was overly complex and would require the creation of a suite of DAs or a modular interactive design. Thus, development of DT LVAD DAs became the short-term goal.

Emotion and Heuristics

In contrast to the majority of existing medical DAs (17), our DT LVAD DAs address emotion throughout, since emotions play such a large part in this decision process (12). Displaying empathy and responding to patients’ emotions have been shown to decrease patients’ anxiety and increase their trust and effective communication with the provider (18–20). Additionally, the Dual-Process Theory of decision-making argues that people make decisions either intuitively, drawing on past experiences and emotions, or rationally, using an analysis dominant and reasoned process (21). More recent advances in decision theory suggest that both the cognitive and emotional aspects of decision-making occur simultaneously and are not separable (20).

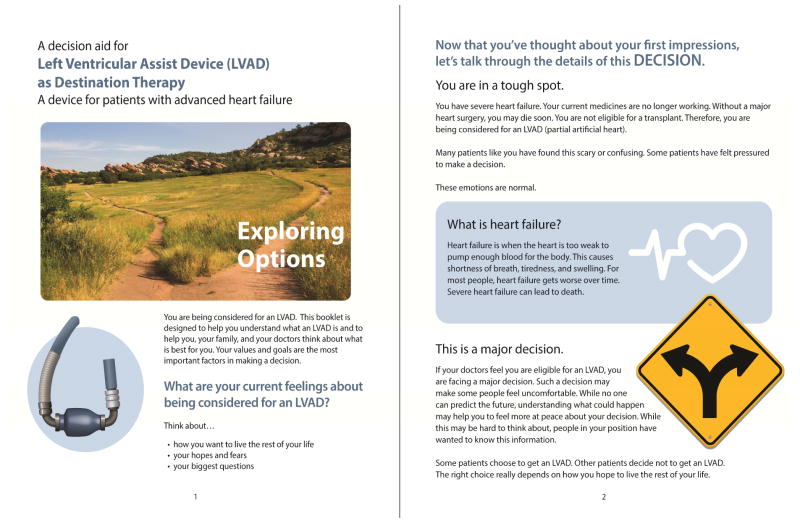

While traditional DAs often focus on the cognitive aspects of decision-making, our DAs support both the emotional/intuitive and cognitive/rational aspects. Over time, the DAs evolved to solicit emotions more directly, validate common feelings, and invite patients to explicitly consider their hopes and fears. The final paper version included a first page that solely addressed emotions, values, and end-of-life goals, before providing information about treatment (Figure 2). The video format, with its use of testimonials, allowed for even greater exploration of the range of emotion involved in the decision process.

Figure 2. Paper Decision Aid Excerpt.

Addressing emotions and fear on first and second pages.

Fear of Death

Due to the survival mentality many patients have (12), we decided it was crucial to directly attend to patients’ fear of dying by using explicit language normalizing this process. The DAs highlighted how DT LVAD is not a black-and-white choice between life and death but a murky decision about how people want to live the rest of their lives. The video also featured a DT LVAD decliner who stated that death is a process of life. Studies have shown that patients with end-stage illness find it helpful to discuss death, and retrospectively many prefer direct and honest communication (22,23).

Tone and Balance

Due to mixed responses related to tone (patients and caregivers saw the paper DA as too negative, while clinicians worried the DA was overly in favor of LVAD), careful changes were made to the language of the DAs in order to address the concern about negativity, while also keeping the DAs an honest depiction of the decision. A focus on “living” with or without an LVAD was inserted. The language was adjusted until participant comments on bias were equally balanced.

Decision Framing When Both Options Have High Morbidity and Mortality

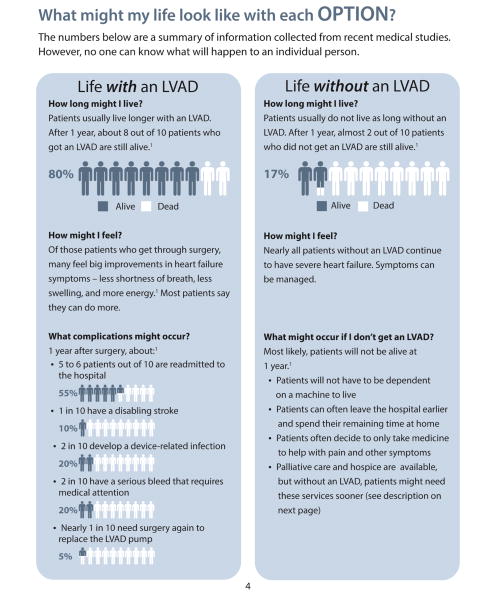

As many patients did not see declining DT LVAD as an option (12) and few existing LVAD educational materials acknowledged there to be a decision (7), we explicitly laid out a dichotomous choice to accept or decline DT LVAD. We presented the LVAD (accepting) and no LVAD (declining) in a column format (Figure 3). The parallel contrast between the two options helped emphasize that DT LVAD is a choice. This reframing was important given the tendency of patients and caregivers to describe the LVAD as a Hobson’s choice, i.e. a choice between something and nothing. The parallel framing concretely showed what the no LVAD option might look like to facilitate viewing the situation as a dilemma, i.e. a choice between two imperfect options. However, because patients who decline DT LVAD have such a high mortality rate, presenting risks and benefits of LVAD declination in a substantive way was a challenge. Ways to present death as an end to the symptoms and burdens of life with heart failure were also explored.

Figure 3. Paper Decision Aid Excerpt.

Page showing options, presenting probabilities, using statistics, and highlighting uncertainty. Due to the majority of people imminently dying without LVAD, this option required unique framing regarding benefits, risks, and burdens.

Turning Complex Data into a Meaningful Summary

Although the event rates included in the DA were backed by a formal systematic review, all stakeholders emphasized the importance of conveying “the big picture” so that patients could compare complex trade-offs in a digestible way. Following the tenets of fuzzy-trace theory, we iteratively refined our presentation to merge emotive and cognitive aspects of decision-making to show statistics in a meaningful and practical way (Figure 3) (24). Additionally, uncertainty of outcomes was reiterated throughout the DAs. While discussion of uncertainty is considered an element of informed decision-making (10), conveying the uncertainty for individual patients is even more critical in the heterogeneous and dynamic setting of end-stage heart failure.

Burdens Emphasized

Lifestyle considerations and everyday burdens for LVAD patients are much greater than for other cardiac therapies, and patients conceptualize these burdens separately from risks (12). Therefore, burdens were highlighted in a section separate from risks. The video DA depicted aspects of lifestyle changes to provide concrete examples of potential burdens.

Palliative and Hospice Care

Palliative and hospice care were integrated into the DAs as an important and prominent resource for patients, and were given their own section to highlight their applicability. Additionally, palliative care and hospice were highlighted not as the alternative to LVAD, but rather as resources for both decision paths, re-emphasizing that all treatment options lead to a common end, and multiple therapies often overlap.

Caregiver Integration

Due to substantial caregiver involvement, we created DAs that explicitly support the patient and caregiver together. Entire sections of the DAs were devoted to caregiver concerns and needs. To strike a balance between encouraging family involvement in the decision and promoting patient autonomy, statements empowering the patient were blended with statements advocating discussions with caregivers.

Use of Explicit and Implicit Values Clarification and Controlled Testimonials

The paper DA contained an entire page devoted to explicit values clarification exercises, including a quantity versus quality of life scale and a pros and cons list for each option. Both DAs used implicit values clarification through language at the beginning and end asking patients to consider their values, goals, and imagined futures (25). The DAs also contained a balanced presentation of patient and caregiver experiences. These testimonials helped provide a voice to values, decision-making processes, and real world experiences. However, the evidence behind the use of patient testimonials is conflicting. While testimonials can be beneficial in helping people understand, remember, and relate to information, they can also be biasing; concerns have been raised about the biased use of relatively healthy LVAD recipients in routine education (8,26–28). We made a conscious effort to include a wide range of experiences that were balanced and showed a range of perspectives. In addition, we focused on testimonials that were primarily process- and experience-focused, as recommended by IPDAS and others (10,28). Quotations were used in the paper DA, and interview clips were used in the video.

Final Versions

The DAs were deemed final after we addressed all known concerns and no new suggestions arose during interviews. Over the entire development process, 32 Acceptability Questionnaires (16) were completed by patients and caregivers: 1) 78% rated the DAs as having “about the right amount of information”; 2) 62.5% rated them as “completely balanced”; 3) 72% reported the DAs did not present one option as the best overall choice; 4) 53% responded that “everything” was clearly presented in the DAs; 5) 69% reported the DAs were “very” helpful in assisting with decision-making; and 6) 75% would “definitely” recommend the DAs to someone facing the same decision.

The final paper DA was at an 8th grade reading level by both the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook and Fry readability tests. Both paper and video DAs scored a 33 out of the 35 applicable IPDAS criteria, based on IPDASi version 4.0 (10). The two criteria not met are part of the “Evaluation” dimension, which asks for evidence of improvement in knowledge and preferences-decision match. Following the Ottawa Decision Support Framework, the next step is to formally test the DAs among the intended audience, specifically assessing whether they increase knowledge and values-treatment concordance for patients. This implementation study has been funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute and began in December 2014. The final DAs are available for clinical use and can be found at www.patientdecisionaid.org and are registered and listed on the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute’s website, https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/index.html.

DISCUSSION

The development of the first IPDAS-level DAs for DT LVAD described here provides not only an important tool for patients, caregivers, and their health care providers confronting end-stage heart failure, but also advances the field of decision support for invasive technologies for progressive life-threatening illness. In the current shared decision-making climate, DAs have become popular for operationalizing shared decision-making (6). Decision aids anchor and enhance, rather than replace, discussions between patients, caregivers, and providers. DAs must be coupled with other decision support, particularly in high-stakes clinical situations exemplified by DT LVAD.

The DT LVAD DAs presented here go beyond IPDAS criteria to address decision-making needs amplified by or even unique to the DT LVAD decision-making process. First, and most notable, is the DAs’ approach to addressing intense emotion, which is relatively uncommon for decision-support tools. While addressing emotions and goals in the opening section of the DAs is atypical, we learned from our needs assessment that fear of death often dominates the consciousness. A major, invasive intervention designed to delay impending death, like a DT LVAD, appeals directly to a primal human desire for self-preservation (29,30). Kahneman and Tsversky’s well-known Prospect Theory describes how, when faced with loss, people tend to be risk seeking (21). To truly support patients in making informed decisions that are concordant with their values and goals, we found that the decision-making process must first acknowledge the inherent fear that patients and caregivers are experiencing, which can then open them to better consider the benefits, risks, and burdens of their options.

Including and highlighting the caregiver stakeholder was another important aspect of the DAs. More than other cardiac treatments, LVADs require a high-level of caregiver involvement, which comes with a host of potential burdens (3,4). Caregivers have described the experience as similar to being a “new mom again caring for a newborn,” while one study raised concerns that caregivers are not well prepared for the terminal nature of DT LVADs (3). With these considerations, along with supporting results from our own caregiver needs assessment (13), we found it of paramount importance to directly engage caregivers as key stakeholders in the decision-making process. By including caregiver information in the patient-directed DAs, we allow the caregiver to have significant involvement in the process, along with helping to further highlight the caregiver’s role for the patient’s own understanding.

Lessons learned through this development process may be valuable in creating DAs for other aggressive therapies for end-of-life illnesses. Other treatments and disease paths contain complex tradeoffs that could also cause emotional distress and fear of death (22,31). Utilizing the practices proven in this paper, development of other DAs that elicit patient needs, involve family caregivers, and are accepted and used by clinicians is possible.

A number of considerations and limitations should be acknowledged. Feedback was obtained from participants at a single implanting center among primarily married, white male patients and female caregivers, and thus may not represent regional or social differences in culture and medical decision-making. However, we did obtain feedback from clinicians across the country, which helped to assure that acceptability likely extends beyond our institution. Additionally, the paper DA has been translated into French by a center in Montreal, Canada. In the future, we plan to provide and test further versions of the DAs that are culturally responsive (e.g., a Spanish language version). We also plan to update the DAs as LVAD technology and outcomes data change. Our DAs were designed in an easily adaptable format, where sections with updated data and figures can be easily inserted between more stable narrative pieces. These DAs target patients actively being considered for DT LVAD, despite challenges regarding final eligibility for LVAD, ambiguity around DT indication, medical complexity, and frequent clinical instability. These issues make subsequent work around dissemination and implementation all the more important.

CONCLUSION

Learning how to help patients with chronic, progressive illness and their caregivers make decisions about highly invasive and potentially life-prolonging interventions is an area of increasing need. If not used properly, these “options” have the potential to harm patients, burden families, and waste societal resources. DT LVAD offers an ideal prototype for exploring decision support in this high-stakes setting. Our DAs are the first IPDAS-level materials for DT LVAD, which contain unique features that pertain specifically to this patient population. These DAs offer nuanced approaches to standardize information within the complexity of decision-making for end-stage illness.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES.

Competencies in Medical Knowledge 1

Compared to traditional consent forms or widely used industry materials, providing DAs that present balanced and easily digestible information, elicit values and goals, and address emotions and fears can be more helpful in education and decision-making for patients considering DT LVAD.

Competencies in Medical Knowledge 2

Addressing emotion and considering psychological heuristics when discussing invasive therapies for end-of-life illnesses can be helpful in promoting high-quality decision-making. This engagement, along with presenting necessary statistical and medical information, can help attend to both cognitive (“reflective”) and emotional (“automatic”) aspects of end-of-life decision-making and reach patients who make decisions in different ways.

Translational Outlook 1

Formal testing of these DT LVAD DAs should be conducted to assure their efficacy in helping patients and caregivers make value-concordant decisions. How the DAs affect knowledge and value-concordant decision-making should be assessed in real world clinical practice.

Translational Outlook 2

Development of these DT LVAD DAs may help with development of DAs for other invasive therapies for end-of-life illnesses and could ensure this process is beneficial for similar situations.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT: This project was partially supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute under its Communication and Dissemination program (PCORI #CDR 1310-06998) as well as the University of Colorado Department of Medicine Early Career Scholars Program. Dr. Matlock is supported by a career development award from the National Institutes on Aging (K23AG040696). Dr. Allen is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL105896.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DA

decision aid

- DT

destination therapy

- IPDAS

International Patient Decision Aid Standards

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- MCS

mechanical circulatory support

Footnotes

RELATIONSHIP WITH INDUSTRY: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jocelyn S. Thompson, Email: jocelyn.thompson@ucdenver.edu.

Daniel D. Matlock, Email: daniel.matlock@ucdenver.edu.

Colleen K. McIlvennan, Email: colleen.mcilvennan@ucdenver.edu.

Amy R. Jenkins, Email: amy.jenkins@ucdenver.edu.

Larry A. Allen, Email: larry.allen@ucdenver.edu.

References

- 1.McIlvennan CK, Magid KH, Ambardekar AV, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Allen LA. Clinical outcomes after continuous-flow left ventricular assist device: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:1003–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grady KL, Meyer PM, Dressler D, et al. Longitudinal change in quality of life and impact on survival after left ventricular assist device implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magid M, Jones J, Allen LA, et al. The Perceptions of Important Elements of Caregiving for a Left Ventricular Assist Device Patient: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1928–52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, et al. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:716–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iacovetto MC, Matlock DD, McIlvennan CK, et al. Educational resources for patients considering a left ventricular assist device: a cross-sectional review of internet, print, and multimedia materials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:905–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.000892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIlvennan CK, Matlock DD, Narayan MP, et al. Perspectives from mechanical circulatory support coordinators on the pre-implantation decision process for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices. Heart Lung. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King JS, Moulton BW. Rethinking informed consent: the case for shared medical decision-making. Am J Law Med. 2006;32:429–501. doi: 10.1177/009885880603200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward Minimum Standards for Certifying Patient Decision Aids: A Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Med Decis Making. 2013;34:699–710. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter A, Stilwell D, Kryworuchko J, Mullen PD, Ng CJ, van der Weijden T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIlvennan CK, Allen LA, Nowels C, Brieke A, Cleveland JC, Matlock DD. Decision making for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices: “there was no choice” versus “I thought about it an awful lot”. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:374–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIlvennan CK, Jones J, Allen LA, et al. Decision-making for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices: implications for caregivers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:172–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottawa Decision Support Framework; University of Ottawa, editor. Ottawa Hospital Research Support Institute. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matlock DD, Spatz ES. Design and testing of tools for shared decision making. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:487–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor AM, Cranney A. User Manual - Acceptability. Ottawa, Ontario: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 1996. [Accessed June 13, 2013]. [updated 2002]. Available at: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Acceptability.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to Promote Shared Decision Making in Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. JAMA internal medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodlin SJ, Quill TE, Arnold RM. Communication and decision-making about prognosis in heart failure care. J Card Fail. 2008;14:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams K, Cimino JE, Arnold RM, Anderson WG. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Power TE, Swartzman LC, Robinson JW. Cognitive-emotional decision making (CEDM): a framework of patient medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahneman D. Thinking fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:868–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McSkimming S, Hodges M, Super A, et al. The experience of life-threatening illness: patients’ and their loved ones’ perspectives. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:173–84. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Pignone MP. Decision making and cancer. Am Psychol. 2015;70:105–18. doi: 10.1037/a0036834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne JWBJ, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Gregory R. Measuring constructed preferences: Towards a building code. Elicitation of Preferences. 2000:243–275. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaffer VA, Hulsey L, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. The effects of process-focused versus experience-focused narratives in a breast cancer treatment decision task. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:255–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bekker HL, Winterbottom AE, Butow P, et al. Do personal stories make patient decision aids more effective? A critical review of theory and evidence. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaffer VA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. All stories are not alike: a purpose-, content-, and valence-based taxonomy of patient narratives in decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:4–13. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12463266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. The causes and consequences of a need for self esteem: A terror management theory. In: Baumeister R, editor. Public self and private self. New York: Springer Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S. A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: an extension of terror management theory. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:835–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:200–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]