Abstract

Background:

The challenging task of postoperative pain relief comes within the realm of the anesthesiologist. Combined spinal epidural (CSE) anesthesia can be used as the sole technique for carrying out surgical procedures and managing postoperative pain using various drug regimes. Epidural administration of opioids in combination with local anesthetic agents in low dose offers new dimensions in the management of postoperative pain.

Aims:

Comparative evaluation of bupivacaine hydrochloride with nalbuphine versus bupivacaine with tramadol for postoperative analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries under CSE anesthesia to know the quality of analgesia, incidence of side effects, surgical outcome and level of patient satisfaction.

Settings and Design:

A prospective, randomized and double-blind study was conducted involving 80 patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I and II coming for elective lower limb orthopedic surgeries carried under spinal anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

Anesthesia was given with 0.5% of 2.5 ml bupivacaine intrathecally in both the groups. Epidurally 0.25% bupivacaine along with 10 mg nalbuphine (group A) or tramadol 100 mg (group B) diluted to 2 ml to make a total volume of 10 ml was administered at sensory regression to T10.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were collected, compiled and statistically analyzed with the help of MS Excel, EPI Info 6 and SPSS to draw the relative conclusions.

Results and Conclusions:

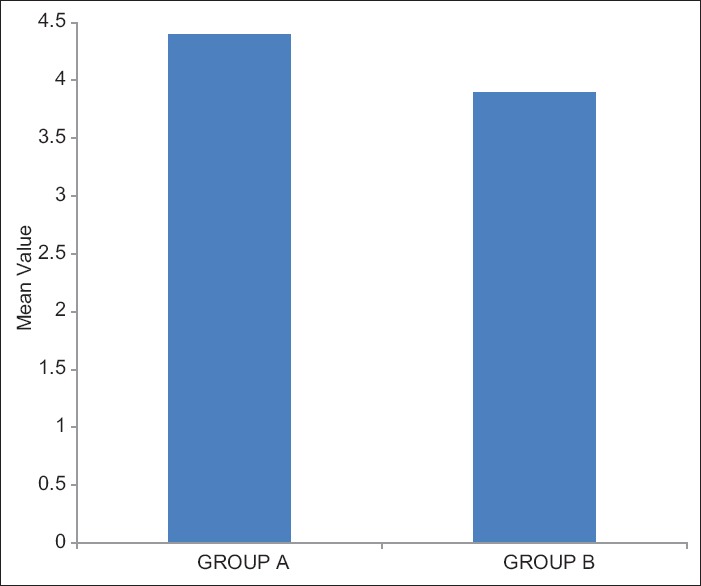

The mean duration of analgesia in group A was 380 ± 11.49 min and in group B was 380 ± 9.8 min. The mean sedation score was found to be more in group B than group A. The mean patient satisfaction score in group A was 4.40 ± 0.871 and in group B was 3.90 ± 1.150 which was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). We concluded that the addition of nalbuphine with bupivacaine was effective for postoperative analgesia in terms of quality of analgesia and patient satisfaction score as compared to tramadol.

Keywords: Combined spinal epidural, postoperative analgesia, nalbuphine, tramadol

INTRODUCTION

Surgical patients require effective intra operative as well as post-operative pain control. Epidural and spinal blocks are two major regional techniques with a long history of effective use for a variety of surgical procedures and pain relief. Spinal anesthesia is a simple method requiring small dose of local anesthetic agent to establish dense, immediate and reliable motor blockade,[1] but precipitous hypotension and difficulty in controlling the level of analgesia are major disadvantages of spinal block.[2] However, epidural block technique gives better control of the level of analgesia, lesser hemodynamic changes and can be used for postoperative pain relief by using different drugs such as opioids or local anesthetic agents. The combined spinal epidural (CSE) technique aims to prolong the duration of analgesia during intraoperative period and extending it to the postoperative period.

Use of neuraxial blocks for orthopedic surgery has increased rapidly during the last few decades, with increasing demand for postoperative pain relief and also to decrease the need for intravenous analgesic drugs during the postoperative period. CSE technique fulfills these demands to its maximum effect and is safer and more reliable analgesic technique. Various types of local anesthetics are used in CSE. Bupivacaine is a local anesthetic which belongs to the amide group of anesthetic agents that has been widely used for local infiltration, peripheral nerve blocks, spinal and epidural anesthesia. Various adjuvants have been added to the local anesthetic in an attempt to further minimize the side effects of the local anesthetics and prolong the duration of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. Nalbuphine, a derivative of 14-hydroxymorphine is a strong analgesic with mixed k agonist and µ antagonist properties. The analgesic potency of nalbuphine has been found to be equal to morphine but unlike morphine, it exhibits a ceiling effect on respiratory depression. Nalbuphine has the potential to maintain or even enhance µ-opioid based analgesia while simultaneously mitigating the µ-opioid side effects.[3] Tramadol, in contrast, is a centrally acting analgesic that has minimal respiratory depressant effects,[4,5] because of its 6000-fold decreased affinity for µ receptors as compared to morphine.[6,7] It also inhibits serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the spinal cord. It has the potential to provide effective postoperative analgesia with no risk of respiratory depression after central neuraxial administration.[8] In our study, we carried out a comparative evaluation of bupivacaine hydrochloride with nalbuphine versus bupivacaine with tramadol for postoperative analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries under CSE anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It was a prospective, randomized double-blind study in which 80 patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades I and II in the age group of 20–60 years of either sex scheduled to undergo lower limb orthopedic surgeries under CSE anesthesia were included after the approval from the Institutional Ethical and Scientific Committee and after taking the written informed consent from the patients. Exclusion criteria were: Patients not willing to give consent, bleeding diathesis, on anticoagulant therapy, mentally retarded, patients suffering from asthma, cardiac, renal, hepatic and neurological disorders and morbidly obese patients. Preanesthetic check-up was done a day before surgery. Visual analogue scale (VAS) was explained during preanesthetic visit as 0 no pain, 1–3 cm mild pain, 4–6 cm moderate pain, 7–10 cm severe pain. All the patients were given premedication with tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg orally with a sip of water 2 h before surgery.

Technique

The study was done in a double-blind manner by making 80 coded slips. The persons performing the procedure and carrying out the observation were blinded to drug solution injected. Decoding of drugs was done at the end of the study. The patients were randomly divided into two groups of 40 each. Preoperative baseline respiratory rate, pulse rate, blood pressure (BP), oxygen saturation (SpO2) and electrocardiography of patients were recorded. Intravenous line was secured and all the patients were preloaded with 10 ml/kg body weight of Ringer lactate solution over 15–20 min. After cleaning and draping with sterile sheet, L2-L3 intervertebral space was located and skin wheal raised by 26 gauge needle with 2% xylocaine. Tuohy needle number 18 was introduced, after 2–3 cm insertion, stylet withdrawn and air filled glass syringe was attached to the hub of the needle. The needle was advanced slowly till the epidural space was identified by loss of resistance technique. Then the epidural catheter was inserted. An epidural test dose of 3 ml of xylocaine with adrenaline was injected through the epidural catheter and observed for any motor block or rise in heart rate (HR). Then L3-L4 intervertebra space was identified and 23 gauge spinal needle was introduced. 2.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine heavy was injected intrathecally (in both groups). Surgery was started under spinal anesthesia. Level of sensory blockade was checked by pinprick and motor blockade by modified Bromage scale (0 = able to flex whole lower limb at hip, 1 = able to flex knee but unable to raise leg at hip, 2 = able to flex the ankle but unable to flex knee, 3 = no movement of lower limb). Bradycardia (HR <60 beats/min) was treated with injection atropine sulfate 0.3 mg intravenously. Hypotension (fall in systolic BP >20% of baseline) was treated with injection ephedrine as per requirement. Bolus epidural drugs were given at sensory regression to T10 in the following manner:

Group A: Epidural bolus of 8 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine + 2 ml of nalbupine (10 mg) diluted to make a bolus volume of 10 ml. For top up 5 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine + 2 ml of 1 mg/ml nalbuphine (2 mg) + 3 ml normal saline to make a total volume of 10 ml was given when VAS score became 4 or more

Group B: Epidural bolus of 8 ml of 0.25% of bupivacaine + 100 mg (2 ml) of tramadol to make a total volume of 10 ml. For top up 5 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine + 2 ml of 10 mg/ml of tramadol (20 mg) + 3 ml of normal saline to make a total volume of 10 ml was given when VAS score became 4 or more.

Monitoring

Hemodynamic parameters such as pulse rate, BP, SpO2, respiratory rate were recorded and monitoring was done every 5 min for first 30 min and then every 15 min till the end of the surgery in both the groups. Patients were assessed using VAS score every half hourly for the first 2 h then 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h after giving top up dose of the test drug for intensity of pain, HR, BP, respiratory rate and sedation score. The duration of postoperative analgesia was measured from the time of injection of the first epidural bolus to VAS score of ≥4. Total number and time of top up doses were calculated. Hemodynamic changes, sensory and motor blockade were checked for 30 min after giving top up doses. If analgesia was found to be inadequate even after three epidural top-up doses given 20–30 min apart, patients were given rescue analgesia with injection ketorolac 30 mg intramuscularly. Frequency and doses of the drugs like antiemetics and vasopressors were noted during surgery. Side effects like nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, pruritus, drowsiness and respiratory depression if the present were noted. Sedation score was assessed as: 0 = Fully awake, 1 = slightly drowsy, 2 = asleep but easily arousable, 3 = fully asleep but arousable, 4 = fully asleep but not arousable.

The data from the present study was systemically collected, compiled and statistically analyzed with the help of MS Excel, EPI Info 6 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) and SPSS (IBM) to draw the relative conclusions. The patient's characteristics were analyzed using the Chi-square test applied to nonparametric data while the intergroup comparison of the parameter data was done using the unpaired t-test. The P < 0.05 was considered significant and P < 0.001 was considered highly significant. Power of study was calculated using power analysis and found to be 86.5%. The results were analyzed and blinding was opened at the end of the study.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

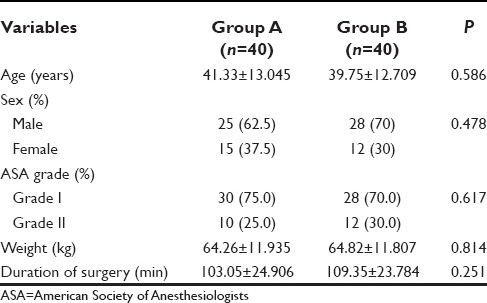

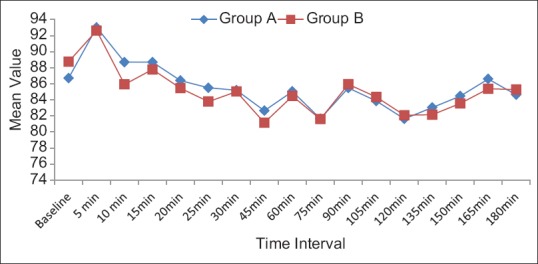

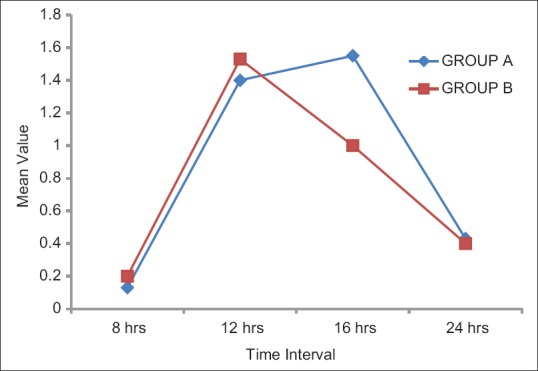

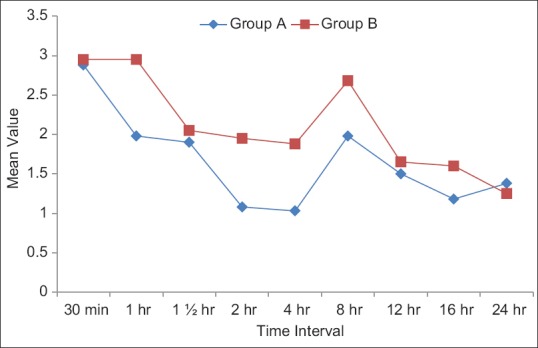

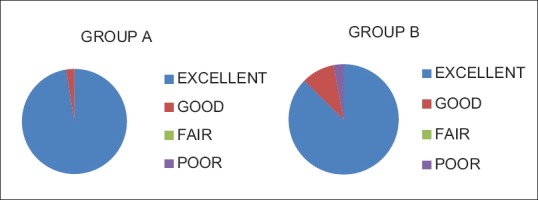

The demographic characteristics of patients were comparable between the two groups regarding mean age, weight ASA grading, diagnosis and duration of surgery [Table 1]. There was no significant difference in HR [Figure 1], systolic BP, diastolic BP and SpO2 during intraoperative period among the two groups. The mean sensory block onset and a maximum motor block of Bromage scale of 3 were comparable in both the groups and was found to be insignificant. The total duration of postoperative analgesia of patients in group A was 380 ± 11.493 min and in group B was 384 ± 9.80 min. The total duration of postoperative analgesia in patients in group B was prolonged as compared to group A but found to be statistically non-significant. The epidural top up was given when VAS was 4 [Figure 2]. The mean number of top-up doses given in group A was 5.08 ± 0.694, as compared to 4.90 ± 0.900 in group B and the difference between the two groups was found to be statistically nonsignificant. The mean sedation score were measured at an interval of 5 min for 30 min for first 2 h and then at 4, 8, 12 and 24 h [Figure 3]. The mean sedation score was different in two groups with the difference being statistically significant and was found to be higher in group B as compared to group A that is, in tramadol group as compared to nalbuphine group due to ceiling effect of nalbuphine on sedation. Quality of surgical analgesia was excellent in 40 (100%) patients in group A, which was seen only in 36 (90%) patients in group B [Figure 4]. It was also good in 4 (10%) patients in group B and this was found to be statistically significant between the two groups. Side effects like nausea, hypotension, bradycardia were comparable in both the groups and found to be statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). The mean patient satisfaction score in the postoperative period in group A was 4.40 ± 0.871 during first 24 h and in group B was 3.90 ± 1.15 [Figure 5] during the same period. The difference in two groups was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). The patient satisfaction score was higher in group A as compared to group B.

Table 1.

Demographic data

Figure 1.

Mean heart rate per minute

Figure 2.

Mean visual analogue scale score

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean sedation score in two groups

Figure 4.

Quality of surgical analgesia in two groups

Figure 5.

Mean patient satisfaction score in two groups

DISCUSSION

Regional techniques, such as spinal and epidural anesthesia may offer advantages over general anesthesia including reduced stress response to surgery and analgesia, which generally extends into the postoperative period.[9,10] The CSE technique gives new dimension to the management of postoperative pain. Any mode of postoperative analgesia must meet three basic criteria: It must be effective, safe and feasible. In the majority of the patients after surgery, pain is not fully relieved with intravenous route of drugs.[11] The discovery of opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord started a new era in the field of postoperative analgesia.[12] Bupivacaine is a local anesthetic, which belongs to the amide group of anesthetic agents that has been widely used for local infiltration, peripheral nerve blocks, spinal and epidural anesthesia. Various adjuvants have been added to the local anesthetics to minimize the side effects of local anesthetics and prolong the duration of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. The duration of postoperative analgesia in patients with the addition of tramadol was more prolonged as compared to nalbuphine. The epidural dose requirement after VAS score 4 and the mean number of top-up doses in 24 h was found to be statistically insignificant in both the groups. Opioids were found to be synergistic with bupivacaine in reducing pain without measurably increasing sympathetic or motor blockade in dog modals.[13] Nalbuphine is an opioid having agonistic action at kappa and antagonist activity at µ opioid receptors and provided reasonably potent analgesia in visceral nociception,[14] was found to improve the quality of postoperative analgesia[15] with fewer side effects. Verma et al.[16] showed that postoperative analgesia was significantly improved by the addition of nalbuphine. Mostafa et al.[17] used bupivacaine mixed with 50 mg tramadol and found that 23% of the patients had nausea and vomiting. This is inconsistent with our study as in group B, 22.5% of the patients had nausea followed by vomiting which is attributed to number of factors like µ receptor-mediated direct stimulation of chemoreceptor trigger zone and it acts as partial agonist at dopaminergic receptors.

In the present study the sedation score was higher in group B as compared to group A as tramadol acts as direct agonist at µ receptors which mediates sedation and nalbuphine acts antagonist at µ receptors and it has ceiling effect on sedation that is, additional sedation does not increase with increasing dose.[3]

Because of fewer side-effects in nalbuphine group, patients were comfortable during sleep or routine activities, so patient satisfaction score was higher in this group.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that both nalbuphine and tramadol were effective for postoperative analgesia when used epidurally in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery. However, nalbuphine group was better in terms of better quality of surgical analgesia, lesser incidence of side-effects and complications e.g. nausea, vomiting and sedation and better patient satisfaction score as compared to tramadol group.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiari A, Eisenach JC. Spinal anesthesia: Mechanisms, agents, methods, and safety. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:357–62. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Datta S, Alper MH, Ostheimer GW, Weiss JB. Method of ephedrine administration and nausea and hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:68–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198201000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunion MW, Marchionne AM, Anderson TM. Use of the mixed agonist-antagonist nalbuphine in opiod based analgesia. Acute Pain. 2004;6:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vickers MD, O'Flaherty D, Szekely SM, Read M, Yoshizumi J. Tramadol: Pain relief by an opioid without depression of respiration. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:291–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarkkila P, Tuominen M, Lindgren L. Comparison of respiratory effects of tramadol and pethidine. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15:64–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1998.0233a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an 'atypical' opioid analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:275–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott LJ, Perry CM. Tramadol: A review of its use in perioperative pain. Drugs. 2000;60:139–76. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alhashemi JA, Kaki AM. Effect of intrathecal tramadol administration on postoperative pain after transurethral resection of prostate. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:536–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andres J, Valia JC, Gill A, Bolinches R. Predictor of patient satisfaction with regional anaesthesia. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:198–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roussel JR, Heindel L. Effects of intrathecal fentanyl on duration of bupivacaine spinal blockade for outpatient knee arthroscopy. AANA J. 1999;67:337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moote C. Technique for postoperative pain management in the adult. Can J Anaesth. 1993;63:189–95. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernards CM. Recent insights into the pharmacokinetics of spinal opioids and the relevance to opioid selection. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004;17:441–7. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200410000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tejwani GA, Rattan AK, McDonald JS. Role of spinal opioid receptors in the antinociceptive interactions between intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:726–34. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199205000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmauss C, Doherty C, Yaksh TL. The analgetic effects of an intrathecally administered partial opiate agonist, nalbuphine hydrochloride. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982;86:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari AK, Tomar GS, Agrawal J. Intrathecal Bupivacaine in comparison with a combination of nalbuphine and bupivacaine for subarachnoid block: A randomised prospective double blind clinical study. Am J Ther. 2013;20:592–5. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31822048db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma D, Naithani U, Jain DC, Singh A. Post operative analgesic efficacy of intrathecal tramadol versus nalbuphine added to bupivacaine in spinal anaesthesia for lower limb orthopaedic surgery. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2013;2:6196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostafa MG, Mohamed MF, Farrag SH. Which has greater analgesic effects: Intrathecal nalbuphine or intrathecal tramadol? J Am Sci. 2011;7:480–4. [Google Scholar]