Abstract

Achondroplasia is a congenital, disfiguring condition which is the most common form of short-limbed dwarfism. Defective cartilage formation is the hallmark of this condition, which results in a wide spectrum of skeletal abnormalities including spinal defects. Various other systems such as cardiac, pulmonary, and neurological can be simultaneously affected adversely including airway defects. Anesthetic management of such individuals is complicated because of their multisystem affliction. Concomitant atlantoaxial dislocation can further amplify the difficulty during the administration of anesthesia in such patients. We report the successful anesthetic conduct of such a patient with the positive outcome.

Keywords: Achondroplasia, anesthesia, atlantoaxial dislocation, ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Achondroplasia is the most common type of skeletal dysplasia resulting in short limb dwarfism (incidence of 0.5–1.5 in 10,000 newborns) associated with failure of endochondral bone formation.[1] Atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) may concurrently exist in achondroplastic patients either de novo,[2] following surgery (foramen magnum decompression)[3] or due to odontoid abnormalities (os odontoideum).[4] Anesthetic management of achondroplastic patients with coexisting AAD offers a complex proposition for anesthesiologists in view of the anatomical and physiological constraints and the possible multisystem involvement. We describe the successful anesthetic management of such a patient undergoing supine transoral odontoidectomy followed by prone posterior fusion after obtaining written consent.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old male achondroplastic (ASAI, 94 cm, 16 kg) diagnosed with AAD and basilar invasion (cervical collar in situ) was scheduled for transoral odontoidectomy and posterior fusion [Figure 1]. Patient had a history of gradually progressive spastic quadriparesis (3/5 power in all limbs) with restricted neck movement. Computed tomography scan of cervicovertebral junction showed hypoplastic dens and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated compressive myelopathy of cord [Figures 2 and 3]. Patient was unable to perform pulmonary function tests. Chest X-ray showed ribs aligned horizontally with decreased intercostal spaces. Routine lab values, electrocardiography, and transthoracic echocardiography were normal. The patient was counseled for awake fiberoptic intubation and the possibility of postoperative mechanical ventilation. He was prescribed 0.25 mg alprazolam and ranitidine 150 mg at night before surgery and morning of surgery. In the operation theater, after connection of monitors, venous access was secured with two 18 gauge cannulas using AV300 Vein Viewing System. Preinduction arterial cannulation was performed under local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance for the beat to beat invasive blood pressure monitoring and for repeated sampling if needed. Awake fiberoptic intubation was achieved with a flexometallic endotracheal tube (7.5 mm ID) following local anesthetic gargling and airway blocks (superior laryngeal and transtracheal). Injections propofol (30 mg) and rocuronium (20 mg) were administered intravenously to induce sleep and achieve muscular relaxation. The patient was then catheterized with a Foley's catheter. Anesthesia was maintained with air and oxygen (50:50) and propofol infusion with intermittent boluses of rocuronium. Injection fentanyl (50 µg) was used for intraoperative analgesia. Throat packing was done to prevent blood aspiration. Transoral odontoidectomy commenced in the supine position and following completion of the same, throat pack was removed, and hard collar reapplied. The patient was then cautiously turned prone over bolsters and horseshoe headrest, taking utmost care not to disturb the alignment or cause any flexion or extension of the neck. Avoidance of direct pressure on the eyes, padding of dependent areas, and unrestricted abdominal excursions were ensured. Blood gas analysis was done twice intraoperatively to gauge the adequacy of ventilation in the prone position. After posterior fusion was completed, the patient was turned supine (after hard collar application) and a nasogastric tube was placed for enteral feeding. Total time needed for the surgery was 7 h during which 350 ml blood was lost occurred, and urine output was 250 ml. Patient remained hemodynamically stable throughout the intraoperative period. The patient was shifted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for elective postoperative ventilation (pressure-controlled mode). Intravenous dexmedetomidine (0.5 µg/kg/h) was used for sedation during ventilation. Analgesia was maintained with paracetamol infusions (250 mg 6 hourly for 3 days). After overnight ventilation, the patient was safely weaned and extubated the following morning. Enteral nutrition commenced 6 h after extubation after ensuring normal blood gases reports on room air. Postoperative respiratory infections were prevented by broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and aggressive physiotherapy and spirometry. Following 2 days of ICU stay, the patient was shifted to ward and 6 days thereafter, was discharged.

Figure 1.

The achondroplastic patient scheduled for undergoing surgery

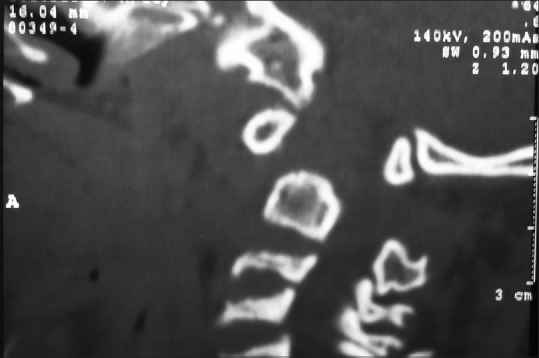

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of cervical region showing dens hypoplasia with atlantoaxial dislocation with basilar invasion

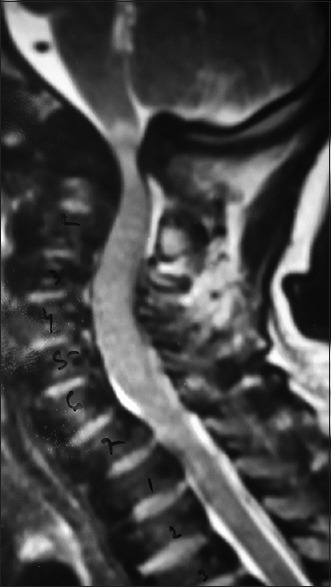

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging cervical spine showing cervico medullary compression.

DISCUSSION

Achondroplasia is the most common form of rhizomelic dwarfism caused by fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 genes mutation disrupting cartilage proliferation and defective enchondral ossification.[1] The associated AAD in our patient necessitated transoral odontoidectomy followed by posterior fusion for surgical correction to avoid compression of the vital cervicomedullary neural structures and neurological disability. Achondroplastic patients have pronounced anxiety compared to other adults.[5] Therefore, proper counseling of the patient as well as anxiolysis was addressed. Placement of peripheral venous lines[6,7] and arterial catheters may be difficult in these patients owing to lax skin and excess subcutaneous tissues [Figure 4]. Anticipating these, we utilized appropriate aids (VeinViewer and ultrasound) for placement of the same preoperatively. Need for ultrasound for proper vascular access has been highlighted previously in a similar case.[7] The prime concern in airway management of this case in the presence of large head, short neck, and fragile atlantoaxial articulation was to avoid movement, which might precipitate neurological deterioration. Traditional airway maneuvers could have aggravated the risk of spinal cord injury. Thus, awake fiberoptic intubation under airway blocks and topical anesthesia was the safest option to secure the airway. Jain et al. while anesthetizing an achondroplastic individual measuring 96 cm required fiber optic bronchoscope to visualize the glottis. Thickened vocal cords necessitated the use of smaller sized endotracheal tube.[7] Literature advises the requirement of lower sized endotracheal tubes than predicted by age for these patients[6] but we had attempted the initial intubation with an age appropriate sized tube and could intubate with a well-lubricated 7.5 mm flexometallic tube through orotracheal route. Its position was then confirmed fiberoptically to avoid endobronchial intubation. The unstable cervical articulation, large head, and weak cervical musculature exerts significant stress on the vital craniovertebral region[8] and was therefore stabilized by application of hard collar before intubation and during positioning. Cardiorespiratory functions may be compromised in achondroplastics due to rib hypoplasia, flattened rib cage, restrictive pulmonary disease, and pectus excavatum which alters functional residual capacity and ventilatory mechanics. Therefore, pressure-controlled ventilation with high respiratory rate and low tidal volume was the appropriate and safer strategy for intra and postoperative ventilation. Pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale may rarely occur in the presence of the respiratory abnormalities[9] in achondroplastic patients. In spite of the fact that these pulmonary abnormalities were not established in our patient, we favored avoiding nitrous oxide. In addition, total intravenous anesthesia afforded us the flexibility of rapid recovery, lower organ toxicity and reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting and hence was preferred. Postoperatively, elective ventilation was crucial considering the development of airway edema and oral pooling of blood and secretions consequent to the transoral surgery. Precipitation of ventilatory insufficiency was also likely due to the anatomical and functional abnormalities of the rib cage. Therefore, the airway was kept secured for ventilation till the edema subsided and for assisting ventilation. Nasogastric tube insertion was done in the immediate postoperative period before significant pharyngeal edema developed to facilitate early enteral feeding. Obstructive sleep apnea is prevalent in a large percentage of achondroplastics[10] which mandates the judicious use of narcotics. Dexmedetomidine was thus favored for ventilatory sedation because of its minimal respiratory depressant properties. Since intravenous paracetamol offered safety, early onset of analgesia and opioid-sparing effect, it was used to address postsurgical pain. Dexmedetomidine also aided in providing supplemental analgesia through synergistic mechanisms via alpha-2 adrenergic pathways (multimodal analgesia) and reducing opioid consumption.[11] Achondroplastics are prone to develop pulmonary complications like atelectasis with pneumonia,[6] hence chest physiotherapy and spirometry were stressed upon postoperatively.

Figure 4.

Loose skin and excessive subcutaneous tissues complicating vascular access

CONCLUSION

Anesthetic management of achondroplastic individuals is complex due to the uncommon variations of their airway, neurological, cardiac, and pulmonary systems, which were compounded because of the associated AAD in our case. However, adequate preoperative planning, intraoperative conduct, and postoperative care can ensure a favorable outcome in such scenarios.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monedero P, Garcia-Pedrajas F, Coca I, Fernandez-Liesa JI, Panadero A, de los Rios J. Is management of anesthesia in achondroplastic dwarfs really a challenge? J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:208–12. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King JA, Vachhrajani S, Drake JM, Rutka JT. Neurosurgical implications of achondroplasia. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:297–306. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.PEDS08344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulati DR, Rout D. Atlantoaxial dislocation with quadriparesis in achondroplasia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1974;40:394–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.40.3.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammerschlag W, Ziv I, Wald U, Robin GC, Floman Y. Cervical instability in an achondroplastic infant. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:481–4. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198807000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalla GN, Fening E, Obiaya MO. Anaesthetic management of achondroplasia. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:117–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/58.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisk EA, Heatley DG, Borowski BJ, Leverson GE, Pauli RM. Obstructive sleep apnea in children with achondroplasia: Surgical and anesthetic considerations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:248–54. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain A, Jain K, Makkar JK, Mangal K. Anaesthetic management of an achondroplastic dwarf undergoing radical nephrectomy. S Afr J Anaesthesiol Analg. 2010;16:77–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohindra S, Tripathi M, Arora S. Atlanto-axial instability in achondroplastic dwarfs: A report of two cases and literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2011;47:284–7. doi: 10.1159/000335433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitra S, Dey N, Gomber KK. Emergency cesarean section in a patient with achondroplasia: An anesthetic diliemma. J Anesth Clin Pharmacol. 2007;23:315–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan BS, Eipe N, Korula G. Anaesthetic management of a patient with achondroplasia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:547–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chetty S. Dexmedetomidine for acute postoperative pain. S Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2011;17:139–40. [Google Scholar]