Abstract

Background:

Postoperative pain control after major abdominal surgery is the prime concern of anesthesiologist. Among various methodologies, epidural analgesia is the most preferred technique because of the excellent quality of analgesia with minimum side-effects.

Aim:

The present study was designated to compare postoperative analgesic efficacy and safety of epidural tramadol as adjuvant to ropivacaine (0.2%) in adult upper abdominal surgery.

Settings and Design:

Prospective, randomized-controlled, double-blinded trial.

Materials and Methods:

Ninety patients planned for upper abdominal surgery under general anesthesia were randomized into three equal groups to receive epidural drug via epidural catheter at start of incisional wound closure: Group R to receive ropivacaine (0.2%); Group RT1 to receive tramadol 1 mg/kg with ropivacaine (0.2%); and RT2 to receive tramadol 2 mg/kg with ropivacaine (0.2%). Duration and quality of analgesia (visual analog scale [VAS] score), hemodynamic parameters, and adverse event were recorded and statistically analyzed.

Statistical Analysis:

One-way analysis of variance test, Fisher's exact test/Chi-square test, whichever appropriate. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

Mean duration of analgesia after epidural bolus drug was significantly higher in Group RT2 (584 ± 58 min) when compared with RT1 (394 ± 46 min) or R Group (283 ± 35 min). VAS score was always lower in RT2 Group in comparison to other group during the study. Hemodynamic parameter remained stable in all three groups.

Conclusion:

We conclude that tramadol 2 mg/kg with ropivacaine (0.2%) provides more effective and longer-duration analgesia than tramadol 1 mg/kg with ropivacaine (0.2%).

Keywords: Epidural analgesia, postoperative pain, ropivacaine, tramadol

INTRODUCTION

The aim of postoperative analgesia is to provide subjective comfort with minimum side-effects, with early ambulation and restoration of function. Pain scores of 4–6 on a 10 visual analog scale (VAS) are not unusual after laparotomy and a large number of patients experienced moderate to severe pain.[1] Moreover, in upper abdominal surgery, the severity of postoperative pain is higher, and it restricts the movement of diaphragm. This increases the incidence of respiratory complications (basal atelectasis, pneumonitis), hospital stay, cost, surgical morbidity, and mortality in such surgeries.

Regional analgesia with the local anesthetic drug via epidural catheter is established method of satisfactory postoperative pain management. Today, among local anesthetic drugs, ropivacaine is preferred due to its favorable sensory block profile and lower cardiovascular toxicity compared to others.[2] Since it is less lipophilic than bupivacaine, its penetration is more selective for thin unmyelinated pain-transmitting nerve fibers compared to larger motor nerve fibers.[3,4]

Morphine in 1981, several studies have provided evidence of prolonged analgesia following its use but nausea/vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, and respiratory depression are associated side-effects with epidural opioids.[5,6] Epidural tramadol also provides prolong postoperative pain relief with advantage of lack of respiratory depressant effect.[7,8]

Tramadol, a synthetic 4-phenyl-piperidine analog of codeine, is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, with synergistic anti-nociceptive interaction.[9] The (+) enantiomer has moderate affinity for the opioids μ receptor and inhibits serotonin uptake, and the (−) enantiomer is a potent norepinephrine synaptic release inhibitor. The result is an opioid with a lack of respiratory depressant effects despite an analgesic potency that has been shown to be approximately equal to that of pethidine in some studies.[7,10,11] Furthermore, animal work has suggested that tramadol may have a selective spinal action.[12,13]

Review of previous literature on postoperative pain control after upper abdominal surgery reveals that the study was done in neonates and pediatrics age group using tramadol as an adjuvant to ropivacaine via caudal technique, while study in adult is lacking. Thus, aim of the present study was to evaluate postoperative analgesic efficacy and safety of single epidural injection of tramadol 1 and 2 mg/kg as adjuvant to 0.20% of ropivacaine in adults following upper abdominal surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Ethical approval and written informed consent, 90 patients of American Society of Anaesthesiologist (ASA) classes I or II aged between 30 and 50 years, of either sex scheduled for elective upper abdominal surgery were included in this prospective, randomized-controlled, double-blinded trial from June 2013 to May 2014. After enrolment in study, patients were explained about postoperative pain assessment on 10-point of which 0 indicates "no pain" and 10 represented "maximum unbearable pain." Patient with a history of end organ dysfunction, morbid obesity, pregnancy, hypersensitivity to local anesthetics or tramadol, and contraindication to epidural anesthesia were excluded from the study.

Premeditations included tablet alprazolam (0.25 mg) and tablet ranitidine (150 mg) administered orally with a sip of water on the evening before surgery, and 2 h before the scheduled procedure. After intravenous (i.v.) cannulation and attachment of standard monitor, anesthesia was induced with fentanyl 2 µg/kg i.v. plus propofol 2 mg/kg i.v. and tracheal intubation was facilitated with vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg i.v. anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane 0.8–1.5%, nitrous oxide 50% in oxygen and fentanyl (1 µg/kg at 30 min interval). Following induction of anesthesia, patients were placed in the lateral decubitus position and an 18-gauge Tuohy needle (Epican Tuohy Needle® 18G; Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was introduced at the T 10–11 interspace in the midline under all aseptic and antiseptic precaution. Epidural catheter was placed after locating the epidural space with the loss of resistance technique (using a syringe containing saline). After ensuring no cerebrospinal fluid or blood backflow from the epidural catheter, a test dose of 3 ml xylocaine containing epinephrine (1:200,000) was administered. The electrocardiogram (ECG) was observed for 2–3 min for tachycardia or T wave changes. In the absence of significant ECG change, patients were turned in the supine position for a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

All patients were randomized (computer generated randomization and concealment via sealed opaque envelope technique) into three equal groups: The solution intended for Group R contained ropivacaine (0.20%), Group RT1 contained ropivacaine (0.20%) with tramadol (1 mg/kg) and Group RT2 contained ropivacaine (0.20%) with tramadol (2 mg/kg). The total volume of drug in either group was 10 ml and given epidurally at the start of incisional wound closure. Randomization was performed by an investigator involved in drug administration and data collection. Data analysis was carried out another investigator blinded to group allocation.

At the end of surgery, patients were extubated after reversal of neuromuscular blockade by injection myopyrrolate (neostigmine plus glycopyrrolate) and shifted to the postoperative care unit (POCU). Further patient care and monitoring were performed by another investigator unaware of group allocation.

Postoperative data for pain, sedation score, hemodynamic parameter, respiratory rate (RR), oxygen saturation were recorded at 0, 15, 30, 60 min then hourly up to 12 h after arrival in POCU. The incidence of associated side effects such as hypotension, bradycardia, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, pruritus, and respiratory depression was recorded during study.

Duration of analgesia of studied drug was defined as the time from study drug bolus epidural injection to the need for the first epidural analgesic requirement. Postoperatively pain was assessed using the 10-point VAS on which 0 indicates “no pain” 1–3-mild pain, 4–7-moderate pain, and 8–10-severe pain. When patient complained pain (VAS ≥ 4), 10 ml ropivacaine (0.20%) with tramadol 1 mg/kg was administered via epidural catheter and if pain relief was inadequate after 20 min, injection paracetamol 15 mg/kg was administered as rescue analgesic.

The sedation score was assessed using the Ramsay sedation score: 1 = anxious or restless, 2 = cooperative and oriented, 3 = asleep and responding to commands, 4 = asleep but strong response to stimulus, 5 = sluggish response to stimulus and 6 = no response to stimulus.

Hemodynamic variables (heart rate [HR], mean blood pressure) were monitored continuously. Incidence of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or >25% below baseline) or bradycardia (<50 beats/min), nausea vomiting, shivering, pruritus, dizziness was recorded and managed as per standard protocols.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated by power and sample size calculator. To detect a 20% difference in the primary outcome between the compared groups with a standard deviation of 25% (estimated from initial pilot observations), 80% power and 5% alpha error (two-sided); a sample size of 26 per group was required. We selected 30 patients per group to compensate for dropouts. Randomization was achieved with the help of computer-generated randomization and concealment via sealed opaque envelope technique. The patient as well as investigator carrying out observation was blinded to group allocation.

The statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The continuous variables were compared by one-way analysis of variance test. Discrete variables were compared by Fisher's exact test/Chi-square test, whichever appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

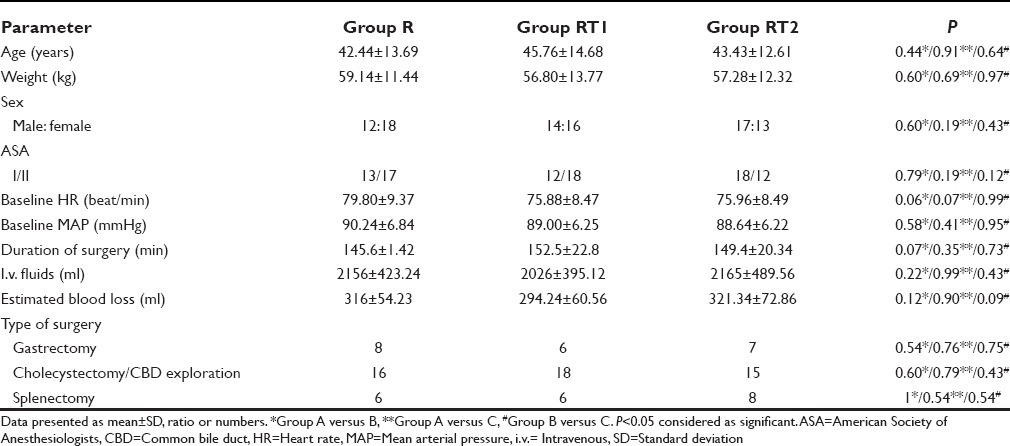

All enrolled patients (90) completed the study successfully, and the study groups were comparable in terms of demographic profile, baseline hemodynamic variables, ASA status, type of surgical procedure, i.v. fluid infused, estimated blood loss, and the duration of surgery [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic data, baseline parameters, and surgical characteristics between the groups (n=30)

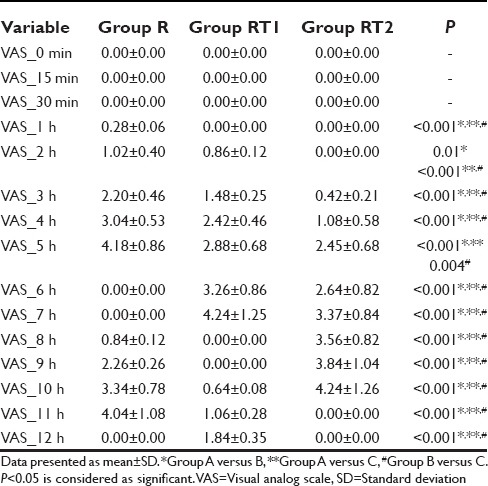

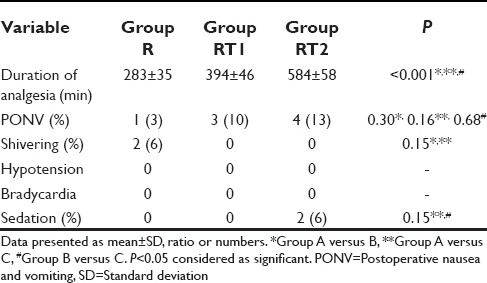

On comparing quality of postoperative analgesia between the groups, it was seen that VAS started increasing after 1 h in Group R, between 1 and 2 h in Group RT1 and after 2 h in Group RT2, but it was lower in Group RT2 than RT1 and R during study [Table 2]. Mean duration of analgesia after first epidural bolus of drug was significantly higher in Group RT2 (584 ± 58 min) when compared with RT1 (394 ± 46 min) or R Group (283 ± 35 min) [Table 3]. The incidence of nausea and vomiting was observed in 3% patients in Group R, 10% patients in Group RT1, and 16% in Group RT2. Sedation was observed in 6% patient of Group RT2, nil in Groups RT1 and R. None of the patients had hypotension, bradycardia, pruritus or respiratory depression or dizziness postoperatively during study period [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of postoperative pain among the groups at different time interval (n=30)

Table 3.

Comparison of postoperative analgesia and side effects between the groups (n=30)

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that after upper abdominal surgery epidural tramadol 2 mg/kg with 0.2% ropivacaine provide more effective and longer-duration analgesia than 1 mg/kg tramadol with 0.2% ropivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine alone.

We selected epidural ropivacaine in this study due to its relative better sensory than motor block profile and lower risk of cardiovascular toxicity compared to previous local anesthetics.[2] Concentration was kept at 0.2% because Scott et al. in a dose-finding study with 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.3% ropivacaine in patients undergoing abdominal surgery demonstrated that 0.2% ropivacaine 10 ml/h provided the best balance between analgesia and motor block.[14]

We used epidural tramadol as adjuvant to 0.2% ropivacaine in this study. Prakash et al. suggested that addition of tramadol to caudally administered bupivacaine provided a dose-related increase in postoperative analgesia.[15] Chrubasik et al. in his study on postoperative pain management in adult concluded that epidural tramadol provides effective, long-lasting analgesia with lack a respiratory depressant effect.[16] Gunduz et al. made similar observations after epidural tramadol administration for postoperative pain management in children.[17]

Previous studies are either with epidural tramadol alone or with bupivacaine or in pediatrics age groups or in lower abdominal/lower limb surgeries. On review of the literature, we are unable to find any study on postoperative pain relief using epidural ropivacaine with tramadol in adult upper abdominal surgeries, so we plan this study.

Our study revealed that the duration of postoperative analgesia was significantly longer with 2 mg/kg tramadol as adjuvant to 0.2% ropivacaine than 1 mg/kg of tramadol with 0.2% ropivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine alone (584 ± 58 min in Group RT2, 394 ± 46 min in Group RT1 and 283 ± 35 in Group R). Delilkan and Vijayan reported that tramadol 100 mg given epidurally in adult patients had a long duration of effective analgesia compared to 0.25% bupivacaine (9.4 vs. 6 h).[18] Siddik-Sayyid et al. and Rathie et al. in their study on epidural tramadol (100 mg) for postoperative pain relief found the duration of analgesia to be 10.26 + 2.73 h.[19,20] Fu et al. reported 11.5 h of analgesia with tramadol 50 mg and 12 h of analgesia with tramadol 75 mg but they observed lower visual pain scores in the 75 mg group.[21]

There were no significant changes in HR, RR, and blood pressure from the baseline with the use of epidural tramadol with ropivacaine in this study. Ertugrul et al. findings on hemodynamic changes with epidural ropivacaine and tramadol were similar to our findings.[22] Baraka et al. compared the perioperative hemodynamic status of two groups of patients undergoing major abdominal surgery who received morphine 4 mg and tramadol 100 mg epidurally and found no difference.[23]

In this study, the incidence of nausea and vomiting was 16% in RT2 Group, 10% in RT1 Group, and 3% in R Group. Baraka et al. reported nausea and vomiting in 20% of patients with epidural tramadol.[23] In another study, nausea and vomiting was observed in 50% of patients treated with tramadol epidurally; the incidence was less with smaller doses.[18]

We observed sedation in 6% patient of Group RT2, nil in Groups RT1 and R during study. Vickers and Paravicini reported the incidence of 1.1% somnolence in their study with epidural tramadol.[24] The incidence of pruritus and respiratory depression was nil during this study. Baraka et al. observed the incidence of 10% itching in of tramadol-treated patients.[23] James et al. in his study concluded that with i.v. tramadol itching is not seen.[25]

Our study has two main limitations. First, a different type of upper abdominal surgeries may have different severity of pain due to handling of tissues and diaphragmatic irritation that leads to a difference in dose and frequency of drug requirements. Second, these results may vary from studies performed on other ethnic groups considering the variations in subjective anesthetic sensitivity may contribute to differences in drug requirement.

Thus, we conclude from present study that epidurally both 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg tramadol as adjuvant to 0.2% ropivacaine were effective for postoperative analgesia in adult patients following upper abdominal surgery but epidural 2 mg/kg tramadol with 0.2% ropivacaine resulted in better quality and longer-duration of analgesia with slightly higher incidence of nausea and vomiting. However, we suggest that more prospective studies are required to recommend tramadol as a useful adjuvant to ropivacaine for enhancing postoperative analgesia in adult upper abdominal surgeries.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuhn S, Cooke K, Collins M, Jones JM, Mucklow JC. Perceptions of pain relief after surgery. BMJ. 1990;300:1687–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6741.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClellan KJ, Faulds D. Ropivacaine: An update of its use in regional anaesthesia. Drugs. 2000;60:1065–93. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen TG. Ropivacaine: A pharmacological review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:781–91. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg PH, Heinonen E. Differential sensitivity of A and C nerve fibres to long-acting amide local anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:163–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semsroth M, Gabriel A, Sauberer A, Wuppinger G. Regional anesthetic procedures in pediatric anesthesia. Anaesthesist. 1994;43:55–72. doi: 10.1007/s001010050033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krane EJ, Dalens BJ, Murat I, Murrell D. The safety of epidurals placed during general anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:433–8. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vickers MD, O'Flaherty D, Szekely SM, Read M, Yoshizumi J. Tramadol: Pain relief by an opioid without depression of respiration. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:291–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senel AC, Akyol A, Dohman D, Solak M. Caudal bupivacaine-tramadol combination for postoperative analgesia in pediatric herniorrhaphy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:786–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045006786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL, et al. Complementary and synergistic antinociceptive interaction between the enantiomers of tramadol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:331–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Flaherty D, Szekely S, Vickers MD. Tramadol versus pethidine analgesia in postoperative pain. Pain. 1990;5:179. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehman KA, Jung C, Hoeckle W. Tramadol and pethidine in postoperative pain therapy: A randomised double-blind trial with intravenous on-demand analgesia. Schmerz Pain Douleur. 1985;6:88–100. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattia A, Vanderah T, Raffa RB, Vaugt JL, Porreca P. Tramadol produces antinociception through spinal sites, with minimal tolerance, in mice. FASEB J. 1991:5–A473. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernatzky G, Jurna I. Intrathecal injection of codeine, buprenorphine, tilidine, tramadol and nefopam depresses the tail-flick response in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;120:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott DA, Emanuelsson BM, Mooney PH, Cook RJ, Junestrand C. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of long-term epidural ropivacaine infusion for postoperative analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:1322–30. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakash S, Tyagi R, Gogia AR, Singh R, Prakash S. Efficacy of three doses of tramadol with bupivacaine for caudal analgesia in paediatric inguinal herniotomy. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:385–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chrubasik J, Warth L, Wust H, Zindler M. Analgesic potency of epidural tramadol after abdominal surgery. Pain. 1987;(Suppl 4):296. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunduz M, Ozcengiz D, Ozbek H, Isik G. A comparison of single dose caudal tramadol, tramadol plus bupivacaine and bupivacaine administration for postoperative analgesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11:323–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delilkan AE, Vijayan R. Epidural tramadol for postoperative pain relief. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:328–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddik-Sayyid S, Aouad-Maroun M, Sleiman D, Sfeir M, Baraka A. Epidural tramadol for postoperative pain after Cesarean section. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:731–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03013907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathie P, Verma RS, Jatav TS, Kabra A. Postoperative pain relief by epidural tramadol. Indian J Anaesth. 1998;42:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu YP, Chan KH, Lee TK, Chang JC, Daiy YP, Lee TY. Epidural tramadol for postoperative pain relief. Ma Zui Xue Za Zhi. 1991;29:648–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ertugrul F, Karakaya H, Purnek F. Comparison of caudal ropivacaine and ropivacaine plus tramadol administration for postoperative analgesia in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004;21:187. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baraka A, Jabbour S, Ghabash M, Nader A, Khoury G, Sibai A. A comparison of epidural tramadol and epidural morphine for postoperative analgesia. Can J Anaesth. 1993;40:308–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03009627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers MD, Paravicini D. Comparison of tramadol with morphine for post-operative pain following abdominal surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1995;12:265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James MF, Heijke SA, Gordon PC. Intravenous tramadol versus epidural morphine for postthoracotomy pain relief: A placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199607000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]