Abstract

Introduction:

The intrathecal administration of combination of drugs has a synergistic effect on the subarachnoid block characteristics. This study was designed to study the efficacy of intrathecal midazolam in potentiating the analgesic duration of fentanyl along with prolonged sensorimotor blockade.

Materials and Methods:

In a double-blind study design, 75 adult patients were randomly divided into three groups: Group B, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine; Group BF, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl; and Group BFM, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl + 1 mg of midazolam. Postoperative analgesia was assessed using visual analog scale scores and onset and duration of sensory and the motor blockade was recorded.

Results:

Mean duration of analgesia in Group B was 211.60 ± 16.12 min, in Group BF 420.80 ± 32.39 min and in Group BFM, it was 470.68 ± 37.51 min. There was statistically significant difference in duration of analgesia between Group B and BF (P = 0.000), between Group B and BFM (P = 0.000), and between Group BF and BFM (P = 0.000). Both the onset and duration of sensory and motor blockade was significantly prolonged in BFM group.

Conclusion:

Intrathecal midazolam potentiates the effect of intrathecal fentanyl in terms of prolonged duration of analgesia and prolonged motor and sensory block without any significant hemodynamic compromise.

Keywords: Analgesia, fentanyl, intrathecal, midazolam

INTRODUCTION

The central neuraxial blockade is one of the most important and most commonly used regional anesthetic techniques for lower abdominal, perineal and lower limb surgeries.

There has been growing emphasis on the advantages of combined pharmacological approach for pain relief. Discovery of analgesic effects of spinally administered opioids and other drugs such as benzodiazepines[1,2] and alpha-2 adrenoreceptor agonists[3] has opened the possibilities of optimizing on useful drug interactions at the level of spinal cord in the management of pain.

By administrating intrathecal combinations of drugs, targeting different spinal cord receptors; prolonged and superior quality analgesia can be achieved by relatively small concentrations of individual drugs. The dose reductions may avoid drug-related side effects. In addition, the simultaneous targeting of several different receptor sites in the spinal cord may lead to improved pain relief.[4]

The advantage of the use of opioids like fentanyl to facilitate effective postoperative analgesia is well documented in the literature.[5,6,7,8]

The administration of intrathecal benzodiazepine has its antinociceptive action mediated via benzodiazepine/GABA-A receptor complex which are abundantly present in lamina II of dorsal horn ganglia of the spinal cord.[9] Intrathecal midazolam also causes the release of an endogenous opioid, acting at spinal delta receptor.[10] This has been proved as its nociceptive effect has been suppressed by “Naltrindole,” a delta selective opioid antagonist.

This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of intrathecal midazolam in potentiating the analgesic effect of intrathecal fentanyl along with a prolonged sensorimotor block in patients undergoing lower limb surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After taking approval from Hospital Ethical Committee and written informed consent, 75 adult patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists I and II, undergoing lower limb surgeries under subarachnoid block (SAB) were enrolled for the prospective, randomized study.

Patients in whom surgery lasted for more than 3 h and with inadequate block requiring supplemental anesthesia were excluded from the study.

After doing a thorough preoperative evaluation, patients were explained about the procedure of lumbar puncture and their participation in the study. They were also explained about visual analog scale (VAS) scale, which they would be shown in the postoperative period. Using computer generated table, patients were randomly divided into three groups. Group B received intrathecally 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 0.7 ml of 0.9% saline. Group BF received intrathecally 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl in 0.5 ml along with 0.2 ml 0.9% saline. Group BFM received intrathecally 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl in 0.5 ml along with 1 mg of midazolam in 0.2 ml.

The test drug was prepared by a person not involved in the study making sure that the total volume of the drug remains 3.7 ml. In the operation theatre, baseline parameters in terms of pulse rate, respiratory rate (RR) and blood pressure were recorded. All patients were preloaded with 15 ml/kg of Ringer's Lactate. After taking adequate aseptic precautions, SAB was administered with the patient in left lateral or sitting position at L3-4 or L4-5 interspace with 23-gauge Quincke spinal needle. The time to attain sensory level up to T10 and time to attain motor block up to modified Bromage grade-3 were recorded. Vital parameters in terms of pulse rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), RR and SpO2 were recorded before administration of SAB, immediately after block (0 min), at 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 min after the procedure and then at 15 min interval thereafter till completion of surgery. Fall in SBP or DBP >20% of the basal value was considered as hypotension. Change in pulse rate 20% of the basal value was considered as bradycardia or tachycardia. Any intraoperative complications such as nausea, vomiting, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, and pruritus were recorded. The total duration of surgery was also noted.

Postoperative analgesia was assessed with VAS. Injection diclofenac sodium 75 mg intramuscularly was administered as rescue analgesia if VAS >3. The total duration of analgesia was also noted. In the postoperative room, vital parameters were recorded every half hourly for 4 hours and then every hourly till the supplementation of rescue analgesia.

Time of recovery from the sensory block, as defined by regression of block up to T12 level, was recorded. Furthermore, time of recovery from motor block to modified Bromage scale-2 was also recorded.

Any postoperative complications such as nausea, vomiting, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, pruritus, and urinary retention were recorded and treatment of complications planned accordingly. The observer involved in the assessment of the parameters was blinded to the test drug used.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 9 (Chicago, SPSS Inc.). Data were presented as mean and standard deviation. Continuous variables were analyzed using ANOVA test, while categorical data were analyzed using Chi-square test. P <0.05 was considered significant. The sample size was calculated based on previous studies with a clinically significant difference of 20% in the duration of analgesia, assuming a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%.

RESULTS

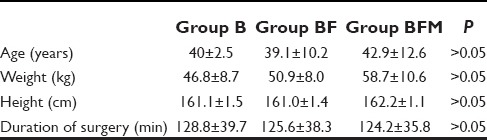

There was no statistically significant variation between the groups in terms of age, weight, height, and duration of surgery [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

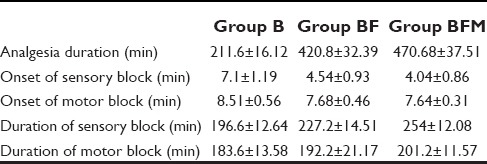

Mean duration of analgesia in Group B was 211.60 ± 16.12 min, in Group BF 420.80 ± 32.39 min and in Group BFM, it was 470.68 ± 37.51 min. There was statistically significant difference in duration of analgesia between Groups B and BF (P = 0.000), between Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000), and between Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.000) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Duration of analgesia and block characteristics

Mean time of onset of sensory block in Group B was 7.1 ± 1.19 min, in Group BF 4.54 ± 0.93 min and in Group BFM, it was 4.04 ± 0.86 min. There was statistically significant difference in time for onset of sensory blockade between Groups B and BF (P = 0.000) as well as Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000). However, there was no statistical significant difference in time for onset of sensory blockade between Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.054).

Mean onset of motor block in Group B was 8.51 ± 0.56 min, in Group BF 7.68 ± 0.46 min and in Group BFM, it was 7.64 ± 0.31 min. There was statistically significant difference in onset of motor blockade between Groups B and BF (P = 0.000) and between Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000). But, there was no clinical or statistical significant difference in onset of the motor block between Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.744).

Mean duration of sensory block in Group B was 196.60 ± 12.64 min, in Group BF 227.20 ± 14.51 min and in Group BFM, it was 254.00 ± 12.08 min. There was statistically significant difference in duration of sensory blockade between Groups B and BF (P = 0.00), Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000) and Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.000).

Mean duration of motor block in Group B was 183.60 ± 13.58 min, in Group BF 192.20 ± 21.17 min and in Group BFM, it was 201.20 ± 11.57 min. There was statistically significant difference in duration of motor blockade between Groups B and BF (P = 0.022), Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000), and Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.010).

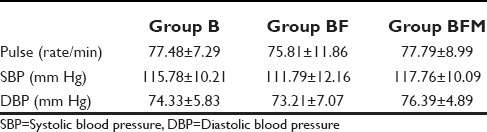

All the baseline parameters in terms of pulse rate, SBP, and DBP were comparable in all the groups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Hemodynamic parameters

The changes in the mean pulse rate between the groups and within the groups were not statistically significant with P = 0.735. Similarly, fall in SBP and DBP was not statistically significant, both within the group, but also between the groups with P = 0.148 and 0.171 respectively.

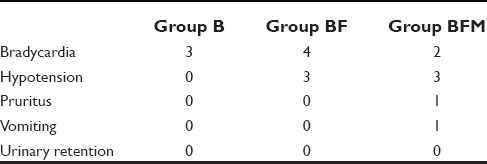

The incidence of side effects was 28% in Group BFM, and 28% in Group BF, whereas it was 12% in Group B [Table 4].

Table 4.

Incidence of side effects

In Group B, three patients had bradycardia whereas none of the patients had hypotension, pruritus, and vomiting. In Group BF, four patients had bradycardia, three patients had hypotension and none of the patients had pruritus and vomiting. In Group BFM, two patients had bradycardia, three patients had hypotension, one patient had pruritus, and one patient had vomiting. There was no incidence of urinary retention in any of the three groups.

DISCUSSION

There was a significant potentiation of the duration of analgesia with the addition of intrathecal midazolam to the bupivacaine fentanyl mixture. Also, there was statistically significant difference in duration of analgesia between Groups B and BF and Groups B and BFM. The administration of a combination of drugs intrathecally targets different spinal receptors resulting in prolonged and superior quality of analgesia.[11] Various studies have observed the prolongation of analgesia with the addition of midazolam or fentanyl. Tucker et al.[1] observed prolongation of the duration of analgesia in labor when a combination of intrathecal midazolam 2 mg and fentanyl 10 mcg was used for labor analgesia. Shah et al.[2] also observed prolongation of the duration of analgesia with the addition of 2 mg intrathecal midazolam to 15 mg bupivacaine and 0.15 mg buprenorphine. Most of the studies done so far have used intrathecal bupivacaine combined with either fentanyl[12,13,14] or midazolam.[15,16,17,18,19] All have shown a significant increase in duration of analgesia.

There was statistically significant difference in time of onset of both sensory and motor block between Groups B and BF (P - 0.000) as well as between Groups B and BFM (P = 0.000). There was no clinically or statistically significant difference in the time for onset of sensory and the motor block between Groups BF and BFM (P = 0.054). The variation in the onset may be because of the fact that though there is fast onset on sensory and motor blockade due to addition of opioid-like fentanyl due to the action on opioid receptors, but there is no potentiation of the effect with the addition of midazolam. Usmani et al.[20] observed a significant difference in time of onset of both sensory and motor block when fentanyl was combined with bupivacaine intrathecally. When intrathecal midazolam was added to the bupivacaine, Agrawal et al.[15] observed no significant difference in onset of sensory and motor blockade time.

There was statistically significant difference in duration of sensory and motor block between Groups B and BF, Groups B and BFM as well as Groups BF and BFM. Bharti et al.[21] observed that the duration of motor and sensory blockade was prolonged when intrathecal midazolam is added to bupivacaine. Grewal et al.[22] also observed significant prolongation of motor block by adding fentanyl to bupivacaine in SAB. Khanna and Singh[13] observed a significant increase in duration of the sensory block with fentanyl when added to bupivacaine intrathecally. Tucker et al.[1] observed prolongation of the duration of the sensory block with intrathecal midazolam 2 mg added to Fentanyl 10 mcg in labor analgesia. Roussel and Heindel[23] did not observe significant prolongation of sensory and motor block when intrathecal fentanyl was added to bupivacaine. Bhattacharya et al.[24] observed no significant prolongation of the sensory block with intrathecal midazolam 2 mg added to bupivacaine 15 mg.

There was no significant variation in pulse rate, SBP, and DBP both within the group and between the groups. In none of the studies,[14,25] there was significant decrease in pulse rate with addition of fentanyl to bupivacaine, however most of the studies were carried out by adding fentanyl in a dose of 25 mcg or less. In this study also there was no significant decrease in pulse rate in Group BFM.

Martyr and Clark[26] found incidences of hypotension as a common complication when intrathecal fentanyl 20 mcg was added to bupivacaine 7.5 mg in elderly patients, but the incidence and severity of hypotension were not significant. Shah et al.[2] observed no significant decrease in mean arterial pressures when intrathecal bupivacaine 15 mg + buprenorphine 0.15 mg was compared with intrathecal bupivacaine 15 mg + buprenorphine 0.15 mg + midazolam 2 mg. Ben-David et al.,[14] Grewal et al.[22] found increased incidence of hypotension by adding fentanyl to bupivacaine in SAB. Bhattacharya et al.[24] did not find any significant change in blood pressure when intrathecal midazolam 2 mg was added to bupivacaine 15 mg.

The incidence of bradycardia was maximum in Group BF while that of hypotension was same in Groups BF and BFM. No incidence of urinary retention was seen in any of the three groups. In all the three groups, the incidence of side effects was not found to be significant (P = 0.510).

Rudra and Rudra[27] observed that when the two groups, one with combination of intrathecal bupivacaine (0.5%) 10 mg with fentanyl 12.5 mcg and other with intrathecal bupivacaine (0.5%) 10 mg and midazolam 2 mg were compared, the incidence of nausea vomiting was found to be less in the group with combination of intrathecal bupivacaine with fentanyl than the group with intrathecal bupivacaine and midazolam combination.

Shah et al.[2] also observed that when intrathecal bupivacaine 15 mg + buprenorphine 0.15 mg was compared with intrathecal bupivacaine 15 mg + buprenorphine 0.15 mg + midazolam 2 mg, incidences of nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, itching, headache, and urinary retention was same in both the groups. These were not found to be significant.

CONCLUSION

Intrathecal midazolam potentiates the effect of intrathecal fentanyl in terms of prolonged duration of analgesia and prolonged motor and sensory block without any significant hemodynamic compromise.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tucker AP, Mezzatesta J, Nadeson R, Goodchild CS. Intrathecal midazolam II: Combination with intrathecal fentanyl for labor pain. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1521–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000112434.68702.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah FR, Halbe AR, Panchal ID, Goodchild CS. Improvement in postoperative pain relief by the addition of midazolam to an intrathecal injection of buprenorphine and bupivacaine. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:904–10. doi: 10.1017/s0265021503001455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boussofara M, Carlès M, Raucoules-Aimé M, Sellam MR, Horn JL. Effects of intrathecal midazolam on postoperative analgesia when added to a bupivacaine-clonidine mixture. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:501–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intrathecal midazolam to improve perioperative analgesia: A meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:365–73. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogra J, Arora N, Srivastava P. Synergistic effect of intrathecal fentanyl and bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. BMC Anesthesiol. 2005;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh H, Yang J, Thornton K, Giesecke AH. Intrathecal fentanyl prolongs sensory bupivacaine spinal block. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:987–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03011070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt CO, Naulty JS, Bader AM, Hauch MA, Vartikar JV, Datta S, et al. Perioperative analgesia with subarachnoid fentanyl-bupivacaine for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:535–40. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belzarena SD. Clinical effects of intrathecally administered fentanyl in patients undergoing cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:653–7. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiyama T, Hanaoka K. Midazolam can potentiate the analgesic effects of intrathecal bupivacaine on thermal- or inflammatory-induced pain. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1386–91. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000057606.82135.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodchild CS, Guo Z, Musgreave A, Gent JP. Antinociception by intrathecal midazolam involves endogenous neurotransmitters acting at spinal cord delta opioid receptors. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:758–63. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox RF, Collins MA. The effects of benzodiazepines on human opioid receptor binding and function. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:354–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200108000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shende D, Cooper GM, Bowden MI. The influence of intrathecal fentanyl on the characteristics of subarachnoid block for caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:706–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.329-az0482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna MS, Singh IK. Comparative evaluation of bupivacaine plain versus bupivacaine with fentanyl in spinal anaesthesia in geriatric patients. Indian J Anaesth. 2002;46:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-David B, Frankel R, Arzumonov T, Marchevsky Y, Volpin G. Minidose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anesthesia for surgical repair of hip fracture in the aged. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:6–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal N, Usmani A, Sehgal R, Kumar R, Bhadoria P. Effect of intrathecal midazolam bupivacaine combination on postoperative analgesia. Indian J Anesth. 2005;49:37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yun MJ, Kim YH, Kim JH, Kim KO, Oh AY, Park HP. Intrathecal midazolam added to bupivacaine prolongs the duration of spinal blockade to T10 dermatome in orthopedic patients. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2007;53:S22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batra YK, Jain K, Chari P, Dhillon MS, Shaheen B, Reddy GM. Addition of intrathecal midazolam to bupivacaine produces better post-operative analgesia without prolonging recovery. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;37:519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MH, Lee YM. Intrathecal midazolam increases the analgesic effects of spinal blockade with bupivacaine in patients undergoing haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:77–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salimi A, Nejad RA, Safari F, Mohajaerani SA, Naghade RJ, Mottaghi K. Reduction in labor pain by intrathecal midazolam as an adjunct to sufentanil. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;66:204–9. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2014.66.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usmani H, Quadir A, Siddiqi MM, Jamil SN. Intrathecal buprenorphine-bupivacaine versus fentanyl-bupivacaine-An evaluation of analgesic efficacy and common side effects. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2003;19:183–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharti N, Madan R, Mohanty PR, Kaul HL. Intrathecal midazolam added to bupivacaine improves the duration and quality of spinal anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:1101–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grewal P, Katyal S, Kaul TK, Narula N. A comparative study of effects of fentanyl with different doses of bupivacaine in subarachnoid block. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2003;19:193–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roussel JR, Heindel L. Effects of intrathecal fentanyl on duration of bupivacaine spinal blockade for outpatient knee arthroscopy. AANA J. 1999;67:337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharya D, Biswas B, Banerjee A. Intrathecal midazolam with bupivacaine increases the analgesic effects of spinal blockade after major gynaecological surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2002;18:183–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kararmaz A, Kaya S, Turhanoglu S, Ozyilmaz MA. Low-dose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anaesthesia for transurethral prostatectomy. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:526–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martyr JW, Clark MX. Hypotension in elderly patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia for repair of fractured neck of femur. A comparison of two different spinal solutions. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:501–5. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0102900509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudra P, Rudra A. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and midazolam for prevention of nausea – Vomiting during caesarean delivery under spinal anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;486:461–4. [Google Scholar]