Abstract

Background and Aim:

Nausea and vomiting causes distress to patients and increases surgical complications. Though various antiemetics are available, their effectiveness and fetal safety profile when used in parturient remains debatable. This randomized, double-blind, comparative study was designed with an aim to compare the antiemetic effects of ondansetron and glycopyrrolate during cesarean section.

Methods:

Sixty-six parturients (American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status I-II) scheduled for elective cesarean section were randomized to receive intravenous ondansetron 4 mg (Group O, n = 32) or glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg (Group G, n = 31) before spinal anesthesia. Outcome measures studied were emesis, episodes of hypotension and bradycardia and pain, till 10 h postoperative. Statistical software used was Epi Info 7 and Microsoft Excel.

Results:

There was no significant difference in nausea and vomiting at all the study intervals between the two groups statistically. There was no difference in episodes of hypotension, but episodes of bradycardia were significantly less in glycopyrrolate group (26%) than in ondansetron group (56%) (P = 0.027). There was no difference in additional analgesic requirements. However, the incidence of dry mouth was significantly greater in glycopyrrolate group (21 [68%]) as compared to ondansetron group (5 [16%]) (P = 0.00).

Conclusion:

Effect of glycopyrrolate on nausea and vomiting during cesarean section are comparable to ondansetron, but with an increased incidence of dry mouth. Glycopyrrolate has no effect on hypotension or additional analgesic requirements, but the incidence of bradycardia is significantly less.

Keywords: Cesarean section, glycopyrrolate, nausea, ondansetron, vomiting

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of nausea in patients undergoing elective cesarean section is 40–81%, especially when the uterus is exteriorized. Intraoperative nausea hampers surgical procedure, while postoperative nausea creates a risk of wound dehiscence, besides causing patient discomfort.[1] Various pharmacological agents have been used to combat nausea and vomiting during cesarean section, with varying success rates and varying side-effects.[2] Ondansetron, a routinely used antiemetic during cesarean section, has no substantial proof of not crossing the placenta or not being excreted in breast milk.[3,4,5] However, due to their good efficacy, they are routinely used in practice.

On the other hand, anticholinergic agents have been demonstrated to possess antiemetic properties by inhibiting central muscarinic and cholinergic emetic receptors.[1,2] However, various studies have shown conflicting results, chiefly due to differences in study design and differences in operative procedures being selected.

We designed this study to compare the antiemetic effects of glycopyrrolate with ondansetron in patients undergoing elective cesarean section under regional anesthesia, with secondary effects on hemodynamic and on postoperative pain.

METHODS

After taking Institutional Ethical Committee Clearance, 66 (American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status I-II) patients undergoing elective lower segment cesarean section under spinal anesthesia were randomized to receive injection ondansetron 4 mg having volume of 2 ml (Group O) or injection glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg diluted to 2 ml with normal saline (Group G), slow intravenously, prior to performance to intrathecal block. Drugs were prepared by an anesthesiologist blind to the nature of study. Study parameters were recorded by another anesthesiologist blind to the type of drug administered and who was also in-charge of the case. Both the investigator and the patient were blind to the drug type being administered. Patients were excluded if they had major systemic or pregnancy related complications, gestation age <34 weeks, history of hyperemesis gravidarum or were on antiemetic medication in the previous week. On the day of surgery, all the patients were given injection ranitidine intravenously preoperatively at least 2 h prior. In the operation theater, baseline heart-rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure and oxygen saturation of the patient were noted. Electrocardiographic monitoring was done throughout the duration of surgery. Intravenous Ringer lactate infusion (500 ml) was started with the aim to be over within 20–30 min. This was followed by the administration of the study drug according to the randomization done with random number table available in the department. Spinal anesthesia was administered under all aseptic precautions in left lateral position with 2.5 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine using 25 gauge Quincke spinal needle. Surgery was allowed to proceed after good quality block was demonstrated by loss of pinprick at T4 dermatomal level. After the delivery of baby, injection oxytocin 5 unit slow bolus and 10 units in infusion to last 30–60 min was given. Patients were monitored for systolic and diastolic blood pressure every 3 min till the delivery of baby and every 5 min thereafter. Heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored throughout the study interval. Postoperatively patients were given injection diclofenac 75 mg, 8 hourly, with first dose given after the patient is shifted to intensive care unit. Supplemental oxygen was administered till the delivery of baby and thereafter if saturation in pulse oximetry dropped to 95%.

Primary outcome of the study was the incidence of emesis during the study interval which was taken as the time from administration of the study drug to 10 h in the postoperative period. Emesis included nausea, vomiting, and retching. Nausea was defined as subjectively unpleasant sensation with awareness of urge to vomit. Retching was defined as rhythmic contractions of abdominal muscles without expulsion of gastric contents. Nausea and retching were noted as a single entity under the heading of nausea and were defined as emesis with no expulsion of gastric contents. Vomiting was defined as a rhythmic contraction of abdominal muscles with the expulsion of gastric contents. The incidence of nausea and vomiting was recorded as a dichotomous variable (yes/no). Measurements were recorded at the end of the intraoperative period and at the end of following time intervals “0–5” and “5–10” h in the postoperative period. A 10 cm Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to measure the severity of each emesis, with “0” being no emesis and “10” being worst possible emesis. Subsequent nausea and vomiting was treated with injection metoclopramide 10 mg intravenous.

Secondary outcome variables studied included episodes of hypotension and bradycardia and postoperative pain. Hypotension was defined as systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg or 20% decrease from the baseline, whichever was earlier. It was treated with an increase in fluid administration, followed by injection ephedrine 5 mg boluses intravenously if no improvement was seen. Bradycardia was defined as heart rate <60/min and treated with injection atropine 0.6 mg.

Postoperative pain was assessed on 10 cm VAS every 2 hourly till 10 h. A score of “0” was taken as no pain and “10“ as worst possible pain. A score of more than 3 was treated with injection tramadol 100 mg in infusion. If no improvement was demonstrated, injection pentazocine 30 mg and injection promethazine 25 mg slow intravenously was administered.

Continuous data were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (range). Categorical variables were expressed as a percentage. Evaluation of continuous data was done using t-test or Mann–Whitney test, while that of categorical data was done using Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, whichever was applicable, depending on the normality of data. Software used was Microsoft Excel and Epi Info 7 (Glycopyrrolate-neon Laboratories Ltd, Palghar, Thane, Ondansetron-intas Pharmaceutical Ltd, Ahmadabad). P < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant. Sample size calculation was done with significance level (alpha) of 5% and power of 80%. Sample size calculation was done taking into account the percentage decrease from actual incidence reported, in either of the experimental groups. Assuming that antiemetic was able to decrease the incidence of nausea by 25% over the actual incidence of reported nausea in cesarean section and taking difference between the two groups to be more than 33% to be clinically relevant, we calculated the sample size to be 30 per group. In order to compensate for drop-outs, we increased the sample size to 33 per group.

RESULTS

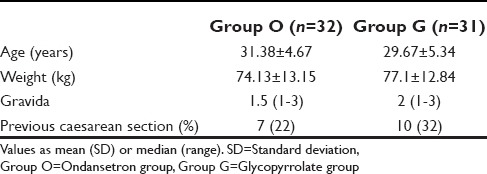

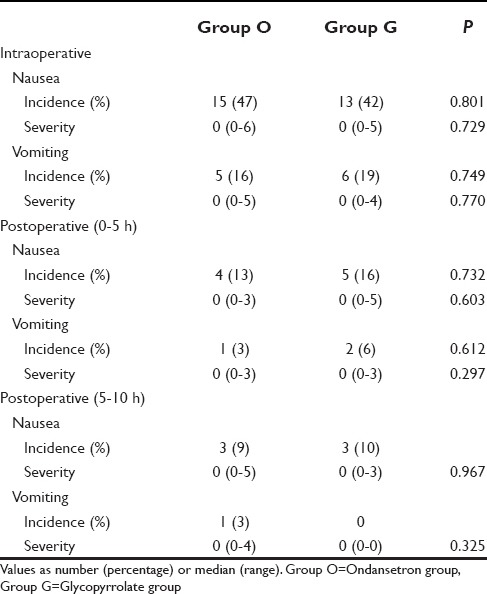

Of 66 patients, three patients had to be dropped from the study. One patient each in ondansetron group (Group O) and glycopyrrolate group (Group G) was dropped from the study as the effect of spinal anesthesia was partial and general anesthesia had to be administered. In another patient in Group G, spinal anesthesia had to be supplemented with ketamine after the delivery of baby. Thus, total patients who successfully completed the study in Group O were 32 and in Group G was 31. Demographic characteristics of all the other patients are summarized in Table 1. The number of patients having nausea and vomiting was comparable in both Group O and Group G at all the intervals intraoperatively and postoperatively [Table 2]. Similarly, the severity of nausea and vomiting, measured on a 10-point VAS showed no significant difference.

Table 1.

Maternal demographic profile

Table 2.

Incidence and severity of nausea-vomiting

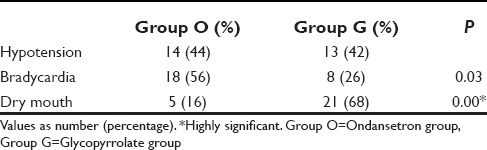

Bradycardia was significantly less in Group G (26%) than in Group O (56%). Thus, glycopyrrolate decreased incidence of bradycardia by 30% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 7–54%). However, the incidence of dry mouth was increased in glycopyrrolate group by 52% (95% CI = 31–73%). There was no difference in the incidence of hypotension between the two groups (44% in Group O and 42% in Group G) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Incidence of side-effects

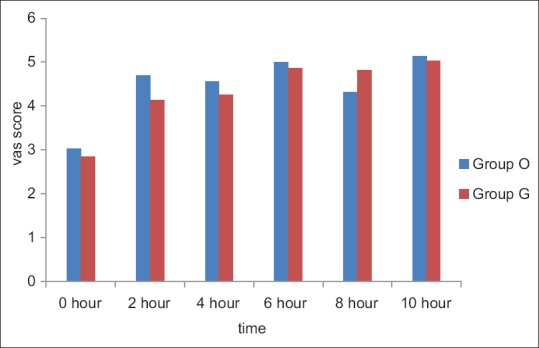

There was no significant difference in mean postoperative pain scores at any time interval between the two groups [Figure 1]. The incidence of additional analgesic requirements also showed no difference in both the groups (31 [97%] in Group O vs. 29 [94%] in Group G).

Figure 1.

Visual Analog Scale scores at various time intervals in the postoperative period

DISCUSSION

Anticholinergics are shown to possess antiemetic properties.[6] Glycopyrrolate, unlike atropine which is a tertiary amine, is a quaternary ammonium anticholinergic agent. Hence, contrary to atropine, it is free of its side effects on the fetus, as it resists passage across placental barrier when administered to the mother. By inhibiting the action of acetylcholine through its action on muscarinic receptors, it decreases volume and free acidity of gastric secretions besides decreasing pharyngeal, tracheal, and bronchial secretions.[7,8] On the other hand, ondansetron causes QT prolongation, besides having unknown fetal safety and associated cost issues.[3,5]

We had comparable incidence as well as the severity of nausea and vomiting throughout the study interval in both the glycopyrrolate and ondansetron groups. Our findings confer to the results by Abouleish et al. and Ure et al., who showed glycopyrrolate and ondansetron, respectively, to be superior to placebo.[4,9] However, Abouleish et al. has reported a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting with ondansetron (nausea 58% and vomiting 36%) as compared to the present study.[4] It could be due to the difference in time of administration of the study drug. They had administered after the delivery of baby. Furthermore, they had a higher incidence of hypotension, which could have further contributed to emesis.[10] Similarly, another study reported a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting with ondansetron than the present study. They had also administered it after the delivery of baby.[11] Biswas et al. have shown significant antiemetic effects of glycopyrrolate when compared to dexamethasone and metoclopramide.[10] In contrast, Yentis et al. demonstrated decreased incidence of nausea and vomiting with glycopyrrolate but significant levels were not reached. However, number of cases studied by them in each group was only 20. Including more cases would have made the result more conclusive.[12]

Bradycardia was significantly less in glycopyrrolate group while there was no difference in the incidence of hypotension between the two groups. These findings are supported by similar results from other studies.[9,11,13] In contrast, some authors have shown hypotensive preventive effects of glycopyrrolate to be similar to ephedrine or phenylephrine.[14,15,16] Another contrasting study by Sahoo et al. showed decreased incidence of hypotension with ondansetron in parturients in comparison to placebo. They postulated it to be due to 5-HT antagonist blocking Bezold Zarisch reflex via 5-HT3 receptors located in intracardiac vagal nerve endings.[17]

Contrary to that shown by Guard and Wiltshire we did not find any difference in postoperative pain scores or incidence of additional analgesic requirements in both the groups.[7] They conducted their study in a different subset of patients, those undergoing laparoscopic sterilization under general anesthesia which could have resulted in contrasting results.

The present results are consistent with findings from other studies regarding incidence of dry mouth, which was significantly higher in glycopyrrolate group.[9,11] This is in contrast to study by Kar et al., who reported decreased incidence of dry mouth which they reasoned to be due to proper preloading of parturient before intrathecal block.[5]

Glycopyrrolate has been evaluated for its many useful effects in the present study. But the incidence of its side effect, which is dry mouth, remains high. Further studies are needed to search for the modalities to reduce this side effect, in order to make the drug more useful in the present scenario. The main deficiency of the present study could be the absence of placebo group. However, various quoted works have compared the two drugs with placebo with almost similar designs as the present study. Furthermore, the practice of inclusion of placebo groups in every study has been questioned.[18]

CONCLUSION

Glycopyrrolate is an effective alternative to ondansetron in reducing intraoperative as well as postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing cesarean section, but with an increased incidence of dry mouth.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fujii Y. Prevention of emetic episodes during cesarean delivery performed under regional anesthesia in parturients. Curr Drug Saf. 2007;2:25–32. doi: 10.2174/157488607779315381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths JD, Gyte GM, Paranjothy S, Brown HC, Broughton HK, Thomas J. Interventions for preventing nausea and vomiting in women undergoing regional anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:9–CD007579. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007579.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanumanthaiah D, Sudhir V. Comment: Ondansetron: Timing and dosage. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:429–30. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.118527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abouleish EI, Rashid S, Haque S, Giezentanner A, Joynton P, Chuang AZ. Ondansetron versus placebo for the control of nausea and vomiting during Caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:479–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kar GS, Ali SM, Stacey RG, Samsoon G. Nausea and vomiting during caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:1021–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.1133y.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harnett MJ, O'Rourke N, Walsh M, Carabuena JM, Segal S. Transdermal scopolamine for prevention of intrathecal morphine-induced nausea and vomiting after cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:764–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000277494.30502.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guard BC, Wiltshire SJ. The effect of glycopyrrolate on postoperative pain and analgesic requirements following laparoscopic sterilisation. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:1173–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb15064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baciarello M, Cornini A, Zasa M, Pedrona P, Scrofani G, Venuti FS, et al. Intrathecal atropine to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after cesarean section: A randomized, controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:781–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ure D, James KS, McNeill M, Booth JV. Glycopyrrolate reduces nausea during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section without affecting neonatal outcome. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:277–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswas BN, Rudra A, Das SK, Nath S, Biswas SC. A comparative study of glycopyrrolate, dexamethasome and metoclopramide in control of nausea and vomiting after spinal anesthesia for caesarean delivery. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:198–200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabalameli M, Honarmand A, Safavi M, Chitsaz M. Treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting after spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: A randomized, double-blinded comparison of midazolam, ondansetron, and a combination. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:2. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.94424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yentis SM, Jenkins CS, Lucas DN, Barnes PK. The effect of prophylactic glycopyrrolate on maternal haemodynamics following spinal anaesthesia for elective caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2000;9:156–9. doi: 10.1054/ijoa.1999.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamchad D, Horrow JC, Nakhamchik L, Santer J, Roberts N, Aronzon B, et al. Prophylactic glycopyrrolate prevents bradycardia after spinal anaesthesia for cesarean section: A randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled, prospective trail with heart rate variability correlation. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23:361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rucklidge MW, Durbridge J, Barnes PK, Yentis SM. Glycopyrronium and hypotension following combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia for elective Caesarean section in women with relative bradycardia. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:4–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngan Kee WD, Lee SW, Khaw KS, Ng FF. Haemodynamic effects of glycopyrrolate pre-treatment before phenylephrine infusion during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22:179–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang J, Min S, Kim C, Gil N, Kim E, Huh J. Prophylactic glycopyrrolate reduces hypotensive responses in elderly patients during spinal anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:32–8. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahoo T, SenDasgupta C, Goswami A, Hazra A. Reduction in spinal-induced hypotension with ondansetron in parturients undergoing caesarean section: A double-blind randomised, placebo-controlled study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avins AL, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Goldberg H, Pressman A. Should we reconsider the routine use of placebo controls in clinical research? Trials. 2012;13:44. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]