Abstract

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a key factor in the protection of hosts against intracellular parasites. This cytokine induces parasite killing through nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species production by phagocytes. Surprisingly, during Leishmania amazonensis infection, IFN-γ plays controversial roles. During in vitro infections, IFN-γ induces the proliferation of the amastigote forms of L. amazonensis. However, this cytokine is not essential at the beginning of an in vivo infection. It is not clear why IFN-γ does not mediate protection during the early stages of infection. Thus, the aim of our study was to investigate the role of IFN-γ during L. amazonensis infection. We infected IFN-γ−/− mice in the footpad and followed the development of leishmaniasis in these mice compared with that in WT mice. CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages migrated earlier to the site of infection in the WT mice, and the earlier migration of these 2 cell types was associated with lesion development and parasite growth, respectively. These differences in the infiltrate populations were explained by the increased expression of chemokines in the lesions of the WT mice. Thus, we propose that IFN-γ plays a dual role during L. amazonensis infection; it is an important inducer of effector mechanisms, particularly through inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, and conversely, it is a mediator of inflammation and pathogenesis through the induction of the expression of chemokines. Our data provided evidence for a pathogenic effect of IFN-γ production during leishmaniasis that was previously unknown.

Introduction

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a key cytokine involved in the protective immune response against infections by intracellular parasites. IFN-γ has been associated with protection in several experimental models of infection, including those using Leishmania major (Wang and others 1994), Trypanosoma cruzi (Torrico and others 1991), Toxoplasma gondii (Suzuki and others 1988), Plasmodium chabaudi (Stevenson and others 1995), Listeria monocytogenes (Buchmeier and Schreiber 1985), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Flynn and others 1993), and dengue virus (Fagundes and others 2011).

This cytokine is particularly critical for the activation of effector mechanisms in phagocytic cells, which leads to parasite killing through the induction of nitric oxide (NO) (Green and others 1990) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Cassatella and others 1990) production. In addition, IFN-γ contributes to the establishment of the inflammatory infiltrate in damaged sites because it is involved in the upregulated expression of chemokines, such as MCP-1, CCL5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 (Rollins and others 1990; Taub and others 1993a, 1993b; Liao and others 1995; Marfaing-Koka and others 1995), and proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-12 (Yoshida and others 1994). Moreover, IFN-γ is important for antigen presentation (Figueiredo and others 1989; Cramer and Klemsz 1997; Beers and others 2003), maintenance of the Th1 polarization of immune responses (Yoshida and others 1994), and inhibition of Th2 cell proliferation (Gajewski and Fitch 1988).

Leishmaniasis is a public health problem throughout the world. This disease affects ∼100 countries, and the estimated number of new cases per year is ∼1.5 million (Alvar and others 2012). Depending on the species of the parasite, the genetics, and the immunological status of the host, the clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis include cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral manifestations (Silveira and others 2004).

The description of 2 different populations of CD4+ T cells, the Th1 and Th2 types (Mosmann and others 1986), had a great impact on the comprehension of murine experimental models of infection by L. major (Sacks and Noben-Trauth 2002). A strong polarization toward a Th1 immune response, associated with high levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 production, is involved in the spontaneous resolution of the disease in C57BL/6 mice (Belosevic and others 1989; Heinzel and others 1993). In contrast, parasite replication is not controlled in BALB/c mice and their susceptibility to the infection is associated with a high level of IL-4 production and a Th2 polarization of their immune response (Sadick and others 1990; Chatelain and others 1992). Although the dichotomy of Th1-based resistance and Th2-based susceptibility is well established for L. major infections, it is not sufficient to explain the development of leishmaniasis in murine experimental infections of Leishmania amazonensis.

L. amazonensis is a new-world species of Leishmania ssp. that has been associated with various clinical manifestations in humans, ranging from the cutaneous to the visceral forms of leishmaniasis (Barral and others 1991). In murine models of infection by L. amazonensis, low levels of IL-4 production were detected (Cortes and others 2010) and treatment using an anti-IL-4 antibody was not sufficient to revert the disease susceptibility of C57BL/10 mice (Afonso and Scott 1993). In addition, the role of IFN-γ during L. amazonensis infection is not clear. In vitro experiments showed that IFN-γ stimulated the replication of the amastigote forms of the parasite in macrophages instead of killing them (Qi and others 2004). Additionally, during in vivo infections, IFN-γ was not required for protection during the early stages of infection (Pinheiro and Rossi-Bergmann 2007).

Because the role of IFN-γ during L. amazonensis infection appears to be controversial, the aim of our study was to better understand how IFN-γ affected the course of an L. amazonensis infection in vivo. Our data showed that this cytokine was important for the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression as well as for the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of infection, the latter of which can be, at least in part, pathogenic to the host.

Material and Methods

Animals

Four- to six-week-old male and female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Centro de Bioterismo (CEBIO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. IFN-γ−/− (B6.129S7-Ifngtm1Ts/J) and iNOS−/− (B6.129P2-Nos2tm1Lau/J) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Glensville, NJ). The mice were maintained under conventional conditions with barriers, a controlled light cycle and controlled temperature. The animals were allowed access to a commercial diet suitable for rodents (Labina-Purina, São Paulo, Brazil) ad libitum. This project was approved by the local ethics committee under protocol CEUA/UFMG 187/2012. The animal care provided was in accordance with the institutional guidelines, which are in accordance with the international guidelines.

Parasites, antigen, and infection

L. amazonensis (IFLA/BR/67/PH8) and L. major (MHOM/IL/80/FRIEDLIN) were maintained in Grace's insect medium (GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cultilab, São Paulo, Brazil), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO). Antigens were prepared from log-phase promastigotes that were washed using 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.3 and were subjected to 7 freeze–thaw cycles. The animals were infected in the hind footpad with 105 L. amazonensis or L. major obtained from stationary-phase cultures (4 or 5 days of culture, respectively). The parasite load was determined using a limiting dilution assay (Sousa and others 2014). The results are expressed as the mean values of the negative logarithm of the titers.

Measurement of arginase activity

The mice were euthanized and the foot tissues were collected at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after infection. Arginase activity in homogenates of the lesions was assayed as described previously (Sousa and others 2014). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of l mol of urea/min. A standard curve was prepared using urea, and the detection limit of the assay was 270 μL of urea.

Cell culture and cytokine assays

Cells obtained from macerated spleens and popliteal lymph nodes were seeded at 5×106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Cultilab), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). The cells were stimulated or not with 50 μg/mL of L. amazonensis antigen. The cell culture supernatants were collected after 72 h to evaluate IFN-γ production by ELISA. To determine the cytokine content at the site of infection, the footpads were collected in PBS supplemented with 50 mg/mL of a complete protease inhibitor cocktail set (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). After homogenization, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and frozen at −80°C until use. The IFN-γ content was assayed using monoclonal antibody (mAb) R46A2, a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse IFN-γ, and peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA). ABTS (Sigma-Aldrich) and hydrogen peroxide were used as the substrates for peroxidase.

The detection limit of this assay was 20 pg/mL. The ELISA to determine the IL-4 content was performed using 11B11 mAb for coating and biotinylated BVD6 mAb (kindly provided by Dr. Phillip Scott, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The detection limit of this assay was 30 pg/mL. The other cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10, were assayed using commercially available kits (BD Pharmigen, San Diego, CA). The detection limit of each of these assays was 32 pg/mL.

iNOS immunoblotting assay

At 8 weeks after infection, foot tissues were collected and homogenized in NETN buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) containing 2% complete protease inhibitor cocktail set (Sigma-Aldrich), after which the mixtures were briefly sonicated.

The lysates were incubated for 10 min in ice, and then the supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 16,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Aliquots containing 30 μg of total lysate proteins were loaded into the wells of a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel containing 8% polyacrylamide. The proteins were transferred from the gel to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was blocked using 5% skim milk in 1 M Tris, 3 M NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) pH 7.4 for 60 min, and then incubated with the primary antibodies. Commercially available antibodies directed against iNOS (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich) and GAPDH (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used. After 3 washes using TBST, the membrane was incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 1 h at room temperature. The labeled bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence and were quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Bone marrow-derived macrophage stimulation and infection

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were prepared as previously described (Edwards and others 2006). The bone marrow was flushed from the femurs and tibias of mice, and the cells were plated in Petri dishes in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine, and 20% conditioned medium obtained from the supernatant of a culture of M-CSF-secreting L929 (LCM) fibroblasts (grown in complete medium). The cells were fed on day 3, and complete medium was replaced on day 7. The cells were used at 10 days for the experiments, and 5×105 macrophages per well were plated overnight in a 48-well plate in DMEM/F12 medium. The cells were then washed and stimulated for 16 h using recombinant IFN-γ (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) at different doses.

The macrophages were then infected or not with stationary-phase promastigotes or amastigotes of L. amazonensis that were isolated from the lesions of BALB/c mice (1:5). After 24 h, the BMDM cells were lysed and the total RNA was isolated for real-time reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays.

Immunohistochemistry of parasites

At 8 and 12 weeks after infection, the lesions were collected from the footpads of the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice and fixed using 10% formaldehyde. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Tafuri and others 2004).

The lesions were dehydrated, cleared, embedded in paraffin, and cut into sections 4–5 μm thick. Endogenous peroxidase activity was abolished using 3.5% hydrogen peroxide (30 v/v) in PBS, after which the slides were incubated with normal goat serum (1:100 dilution) to block nonspecific immunoglobulin absorption. Heterologous hyperimmune serum obtained from a dog that had been naturally infected with Leishmania infantum was diluted 1:800 using 0.1% bovine serum albumin employed as the primary antibody. The slides were incubated in a humid chamber at 4°C for 18–22 h, washed using PBS, incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Ig (LSAB2 kit; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), washed again using PBS, and then incubated with a streptavidin–peroxidase complex (LSAB2 kit; Dako) for 20 min at room temperature. The slides were treated with 0.024% diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.16% hydrogen peroxidase (30 v/v), and finally were dehydrated, cleared, counterstained using Harris's hematoxylin, and mounted with coverslips.

Images were captured using an Olympus BX400 microscope with an Olympus Color 3 camera using the QCapture Pro 6.0 (program QImaging, Surrey, Canada).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

The cells were lysed and the total RNA of the BMDM cells and the homogenized tissues was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a mixture containing 2.5 mM DNTPs (Promega Biosciences, San Luis Obispo, CA), 0.1 M DTT (Promega Biosciences), 7.5 pmol oligo dT15 (Promega Biosciences), RNAsin (Promega Biosciences), reverse transcriptase buffer (Promega Biosciences), and reverse transcriptase (Promega Biosciences). For the real-time RT-PCR assays, 3 μL of cDNA was mixed in a final volume of 10 μL containing SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and 20 μM of primers.

The reactions were performed in MicroAmp® Optical 96-well reaction plates (Applied Biosystems) using an ABI 7900 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Real-time RT-PCR was performed in triplicate for each sample. The levels of β-actin were used as the normalization controls. The results were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| β-ACTIN | 5′-AGGTGTGCACCTTTTATTGGTCTCAA-3′ | 5′-TGTATGAAGGTTTGGTCTCCCT-3′ |

| IFN-γ R1 | 5′-GTGGAGCTTTGACGAGCACT-3′ | 5′-ATTCCCAGCATACGACAGGGT-3′ |

| IFN-γ R2 | 5′-TCCTCGCCAGACTCGTTTTC-3′ | 5′-ACGGCTCCCAAGTTAGAATCT-3′ |

| CXCL9 | 5′-GGGATTTGTAGTGGATCGTGC-3′ | 5′-GGAGTTCGAGGAACCCTAGTG-3′ |

| CXCL10 | 5′-CCTGCCCACGTGTTGAGAT-3′ | 5′-TGATGGTCTTAGATTCCGGATTC-3′ |

| CXCR3 | 5′-GGTTAGTGAACGTCAAGTGCT-3′ | 5′-CCCCATAATCGTAGGGAGAGGT-3′ |

| MCP-1 | 5′-ATGGTCAAGAGTTTGCAGCTT-3′ | 5′-CCTGAATTTTGGGAGAGTGTGAT-3′ |

| ARGINASE I | 5′-CTGGCAGTTGGAAGCATCTCT-3′ | 5′-CTGGCAGTTGGAAGCATCTCT-3′ |

Flow cytometry

Briefly, 4, 8, and 12 weeks postinfection, the mice were euthanized and the lesions were collected from their hind footpads. The samples were incubated for 90 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 in 750 μL of RPMI containing 0.1 mg/mL of Liberase TL (Roche Diagnostics) and 0.5 mg/mL of DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). The reactions were stopped by adding 15 μL of EDTA (0.5 M, pH=8) and 750 μL of RPMI 3% FBS to each sample. The digested lesions were macerated and the macerates were then filtered using a 70-μm pore size Falcon cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Cells in suspension were then washed and counted, after which the concentration was adjusted to 106 cells/100 μL in FACS Buffer (1% FBS in cold PBS). The cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with an anti-Fc-γIII/II (CD16/32) receptor antibody (clone 2.4G2). After removing the blocking solution, the cells were stained with the surface antibodies for 20 min.

The flow cytometric studies were performed using the FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Three Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). The following antibodies were used for surface staining: anti-mouse F4/80 (clone BM8), anti-CD11c (clone N418), anti-MHC II (anti I-Ab, clone AF6 120.1), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11), anti-CD19 (clone 1D3), anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), and anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8). All of the antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Depletion of the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations

mAbs 53-6.72, an IgG2a rat anti-mouse anti-CD8 alpha, and GK1.5, an IgG2b rat anti-mouse anti-CD4, were employed to deplete the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations. mAb GK1.5 was a gift from Dr. Luís Carlos Crocco Afonso (Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil). The hybridoma line secreting 53-6.72 was obtained from Banco de Células do Rio de Janeiro (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). The antibodies were purified from the hybridoma culture supernatants by ammonium sulfate precipitation. The same protocol was applied to deplete the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations. We administered 1 mg/mL of 53-6.72 or GK1.5 by intraperitoneal injections starting at 3 weeks postinfection. During the first week of the treatment, 3 doses were administered every 2 days. Afterward, the mice received 1 dose of the mAbs once a week. As a control, we used rat IgG purified from rat serum (Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical analysis

The comparison of 2 groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney test. For comparison of more than 2 groups, a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's t-test was conducted. Differences were considered significant when P≤0.05.

Results

IFN-γ is not required for the containment of parasite replication and lesion development during the early stages of L. amazonensis infection

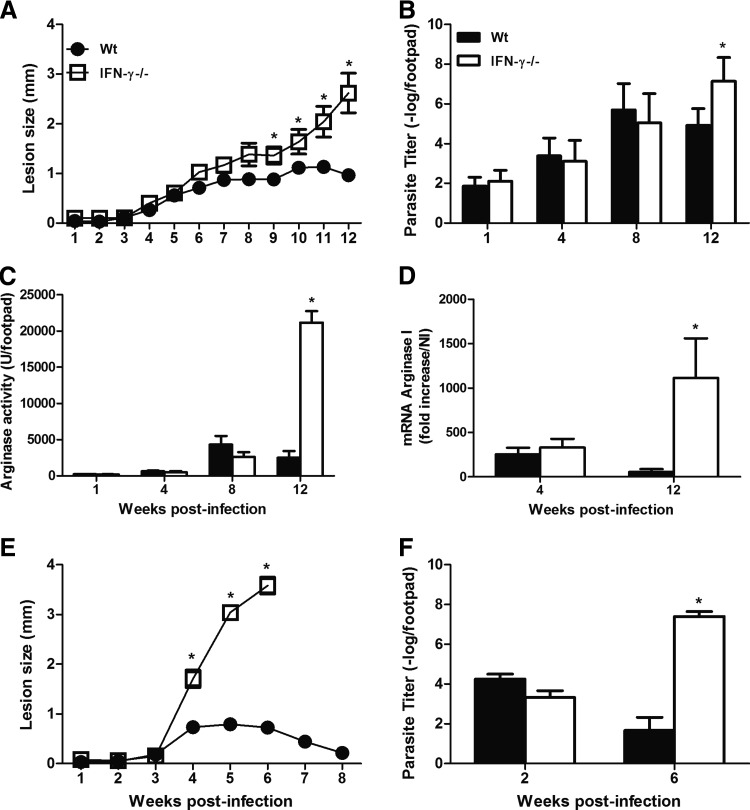

To investigate the role of IFN-γ during L. amazonensis infection, we infected WT and IFN-γ−/− mice with 105 promastigote forms of the parasite. We followed the development of the disease for 12 weeks. Until 8 weeks postinfection, there were no differences between the lesion sizes (Fig. 1A) or the parasite loads (Fig. 1B) of the 2 groups. Afterward, the WT mice showed partial control of the development of the disease, whereas the swelling of lesions and replication of the parasites were not controlled in the IFN-γ−/− mice. These data indicated that IFN-γ played an important role only during the late stages of infection, in contrast to what has been previously described (Wang and others 1994) and to our own findings regarding the L. major infection (Fig. 1E, F).

FIG. 1.

The course of infection in WT and IFN-γ−/− mice after an s.c. infection of the right hind footpad using 105 Leishmania amazonensis (A) or Leishmania major (E) promastigotes. The sizes of the lesions were measured weekly and were expressed as the increase in the footpad thickness. The number of parasites in the lesions was determined using limiting dilution analysis (B, F). The level of arginase activity at the site of infection by L. amazonensis was measured as described in the Materials and Methods section (C), and the levels of host expression of arginase I mRNA at 4 and 12 weeks postinfection by L. amazonensis were expressed as the fold increase compared with that of naive mice (D). * Indicates significant differences between the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. IFN-γ, interferon gamma.

The proliferation of Leishmania has been associated with arginase activity within the lesions (Iniesta and others 2002). Until 8 weeks after infection, no differences were found in the level of arginase activity (Fig. 1C) or its expression level (Fig. 1D) in the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice. However, at 12 weeks postinfection, the increased levels of arginase activity and its expression in the IFN-γ−/− mice compared with those in the WT mice may have been related to the greater number of parasites recovered from the former mice at this time point of infection.

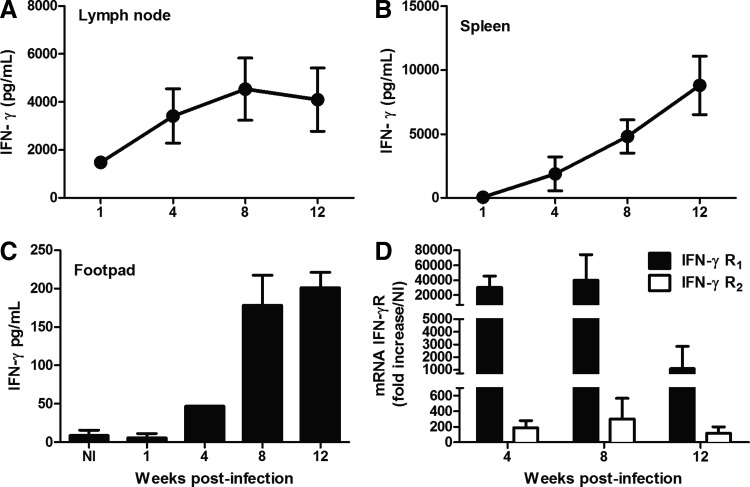

Because these data indicated that there was a delay in IFN-γ production during L. amazonensis infection, our next goal was to perform a kinetic study of IFN-γ production by lymph node and spleen cells after restimulation with a Leishmania antigen. The lymph node cells (Fig. 2A) and spleen cells (Fig. 2B) of the WT mice produced IFN-γ in response to specific antigenic stimulation in culture from 1 to 4 weeks postinfection, respectively. Moreover, from 4 weeks postinfection, we found a higher level of IFN-γ in the lesions compared with that in the naive footpads (Fig. 2C). In addition, we observed the induced expression of both chains of IFN-γR from 4 weeks postinfection (Fig. 2D). Therefore, we suggest that IFN-γ can induce signaling through binding to its receptor after the early stages of infection.

FIG. 2.

WT mice were infected s.c. with 105 L. amazonensis promastigotes, and the kinetics of IFN-γ production by lymph node (A) and spleen (B) cells that were stimulated with a parasite antigen for 72 h in culture was determined. The levels of IFN-γ at the sites of infection (C). Gene expression levels of the R1 and R2 chains of the IFN-γ receptor in the infected footpads (D). The values represent the fold increase in the expression levels compared with those of naïve mice. The results were obtained in 1 experiment that was representative of 3 experiments performed using 5 mice per group at each time point.

iNOS expression is IFN-γ dependent during L. amazonensis infection

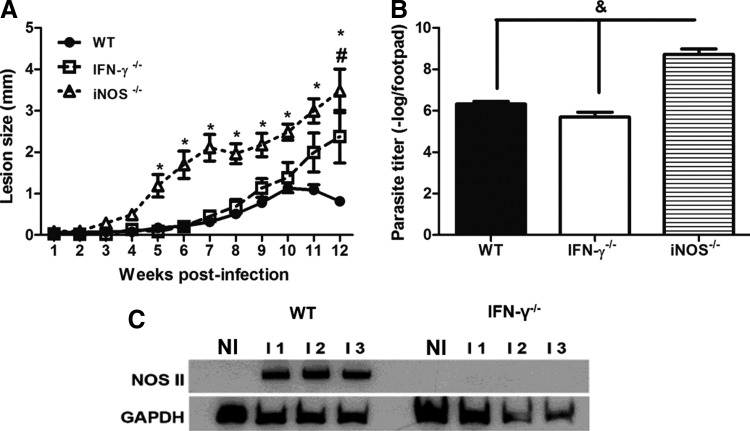

To investigate whether the production of IFN-γ during the early stages of infection was relevant for the containment of parasite replication through the induction of iNOS expression, we compared the development of the disease in WT, IFN-γ−/−, and iNOS−/− mice. As shown in Figure 3A, the iNOS−/− mice had lesions of a larger size from 5 weeks postinfection and higher levels of parasites after 8 weeks (Fig. 3B) compared with those of the other groups. Our data indicated that iNOS played an essential role in the containment of parasite replication and lesion development during L. amazonensis infection after the early stages of infection. Interestingly, lesion development was similar in the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice until 8 weeks postinfection. Therefore, we hypothesized that iNOS expression could be induced in an IFN-γ-independent manner. However, no iNOS expression was found in the lesions of the IFN-γ−/− mice at 8 weeks postinfection. This result is in contrast with the iNOS expression observed in WT mice at 8 weeks postinfection (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Course of infection in WT, IFN-γ−/−, and iNOS−/− mice after an s.c. infection of the right hind footpad with 105 promastigotes of L. amazonensis (A). The sizes of the lesions were measured weekly and were expressed as the increase in the footpad thickness. The number of parasites in the lesions was determined using limiting dilution analysis (B). Tissue homogenates (50 μg of protein each) were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotting was performed using anti-NOS II or using anti-GAPDH as the internal control. NI indicates noninfected mice (C). * Indicates significant differences between the WT and iNOS−/− mice; # indicates significant differences between the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice; and & indicates significant differences when comparing the iNOS−/− mice with the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The data are representative of 3 independent experiments. iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Proinflammatory environment at the site of infection in WT mice

To understand why the IFN-γ−/− mice exhibited a lesion development pattern and a parasite burden similar to those of the WT mice until 8 weeks postinfection in the absence of iNOS expression, we determined the levels of important cytokines that are produced during L. amazonensis infection.

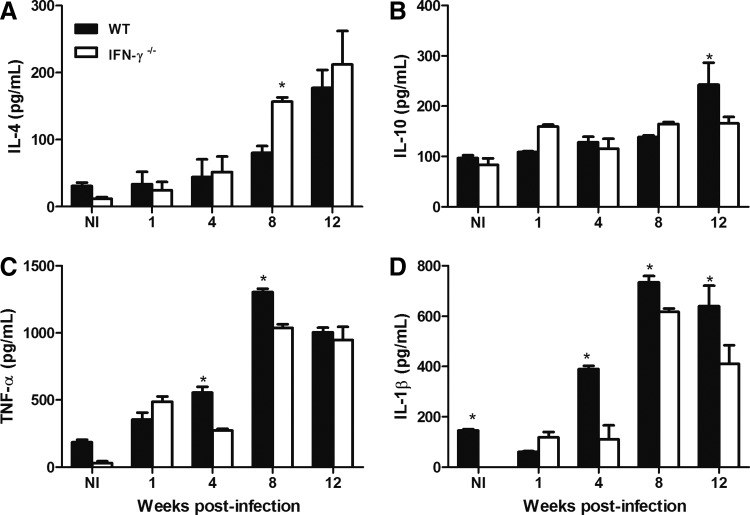

No major differences in the levels of IL-4 production of these groups were observed during the first week of infection. The IFN-γ−/− mice showed an increased level of IL-4 production only at week 8 postinfection (Fig. 4A). In the case of IL-10, we found that the WT mice exhibited a higher level of production at the latest time point observed, at 12 weeks after infection (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we observed impairment in the production of 2 important proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β, in the absence of IFN-γ. At 4 and 8 weeks postinfection, the WT mice showed higher levels of both of these cytokines within the infected footpads (Fig. 4C, D). The IFN-γ−/− mice showed lower levels of IL-1β than those of the WT mice, even at 12 weeks after infection (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

WT and IFN-γ−/− mice were infected s.c. with 105 promastigotes of L. amazonensis and the kinetics of IL-4 (A), IL-10 (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-1β (D) production at the site of infection were determined using ELISAs. NI indicates noninfected mice. * Indicates significant differences between the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The results were obtained in 1 experiment that was representative of 3 experiments performed using 3 mice per group at each time point. IL, interleukin.

Later migration of T cells and macrophages to the site of infection occurred in the absence of IFN-γ

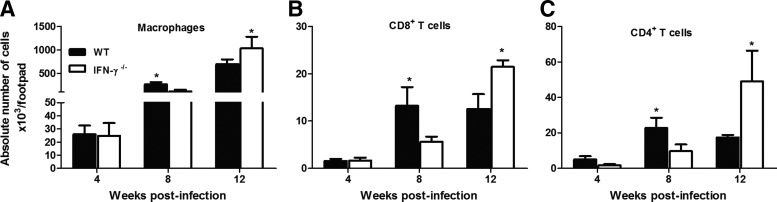

Because IFN-γ may play a role in the migration of inflammatory cells, we investigated how the absence of this cytokine affected the infiltration of inflammatory cells during L. amazonensis infection. Interestingly, at 8 weeks postinfection, there were more macrophages (Fig. 5A), CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5C), and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5B) within the lesions of the WT mice than in those of the IFN-γ−/− mice. The opposite situation was observed at 12 weeks postinfection, when more macrophages and T cells had accumulated in the lesions of the IFN-γ−/− mice.

FIG. 5.

The absolute number of (A) macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+Ly6G−), (B) CD8+ T cells (CD3+CD8+CD4−), and (C) CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+CD8−) at the sites of infection was determined using flow cytometry. WT and IFN-γ−/− mice were infected s.c. with 105 promastigotes of L. amazonensis. * Indicates significant differences between the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The results were obtained in 1 experiment that was representative of 3 experiments performed using 5 mice per group at each time point.

Our data indicated that IFN-γ contributed to the earlier recruitment of macrophages and T cells and did not affect the migration of neutrophils and dendritic cells (data not shown) to the site of infection by L. amazonensis.

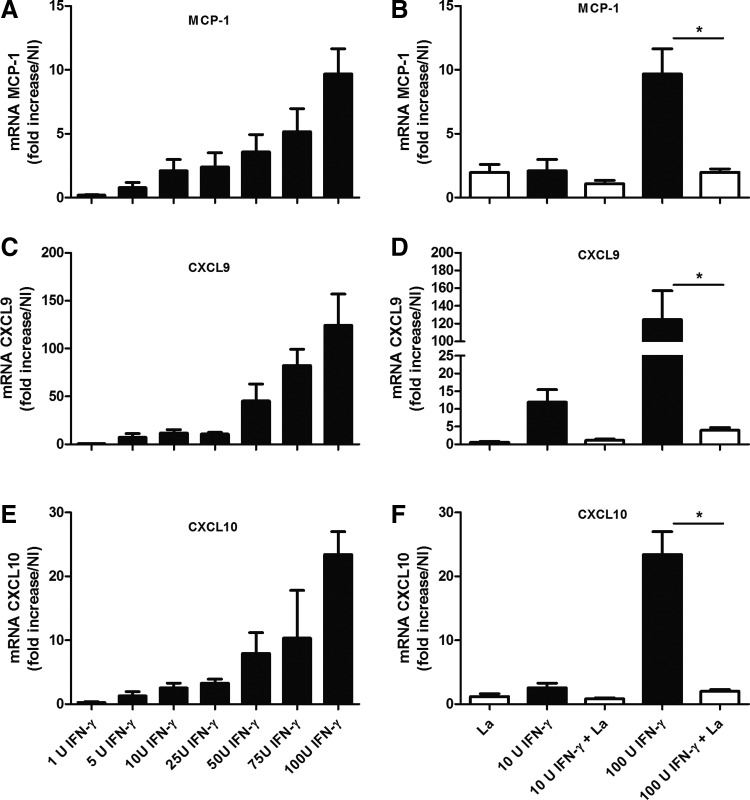

To clarify how IFN-γ affected the migration of inflammatory cells to the site of infection, we activated WT macrophages in vitro using recombinant IFN-γ at different doses. After 24 h, we quantified the expression levels of chemokines using real-time RT-PCR. Interestingly, IFN-γ induced macrophages to express MCP-1 (Fig. 6A), CXCL9 (Fig. 6C), and CXCL10 (Fig. 6E), even when administered at low doses (1 or 5 U). IFN-γ treatment triggered the dose-dependent induction of the expression of all of the chemokines studied. L. amazonensis amastigotes induced the expression of MCP-1 (Fig. 6B) and CXCL10 (Fig. 6F), but not CXCL9 (Fig. 6D), by the WT macrophages. In addition, this parasite inhibited the IFN-γ-induced expression of MCP-1, CXCL9, and CXCL10 (Fig. 6B, D, F).

FIG. 6.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages obtained from WT mice were cultured for 24 h in the presence of IFN-γ at different concentrations in the absence (A, C, E) or presence (B, D, F) of L. amazonensis amastigotes. The expression levels of the MCP-1 (A, B), CXCL9 (C, D), and CXCL10 (E, F) genes were determined using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and were expressed as the fold increases in expression relative to those of naive mice. * Indicates significant differences between the groups in the absence or presence of amastigote forms of the parasite (P<0.05). NI indicates noninfected mice. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

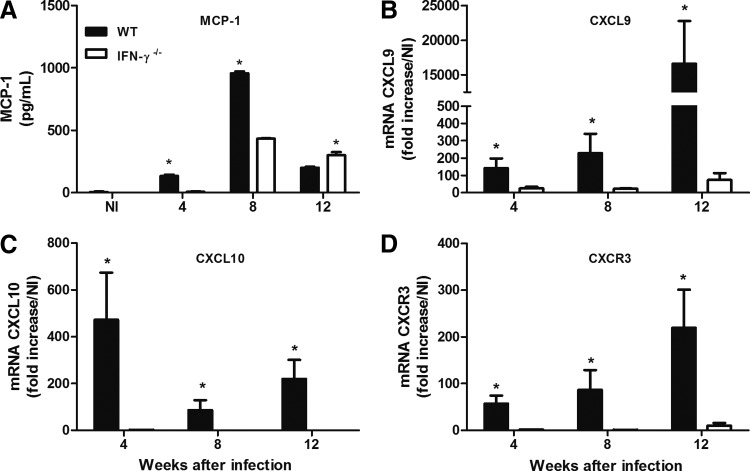

Increased levels of chemokine expression or production in WT mice may be related to the earlier recruitment of macrophages and T cells to their sites of infection

Because we found that IFN-γ induced the expression of chemokines by macrophages in vitro, even when this cytokine was administered at low doses, we decided to determine whether the differences in chemokine expression levels could be observed at the site of infection in the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice. As expected, the expression levels of MCP-1, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCR3 were increased at the site of infection of the WT mice during most of the entire course of infection (Fig. 7A, B, C, D). This increase in chemokine expression during L. amazonensis infection may account for the differences between the inflammatory infiltrates of IFN-γ-producing (ie, WT) and IFN-γ−/− mice.

FIG. 7.

WT and IFN-γ−/− mice were infected s.c. with 105 promastigotes of L. amazonensis, and the kinetics of MCP-1 (A) production in the infected footpad was determined using an ELISA. The expression levels of the CXCL9 (B), CXCL10 (C), and CXCR3 (D) genes at the site of infection were determined using real-time RT-PCR. The data show the fold increases in expression relative to those of naive mice. * Indicates significant differences between WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). NI indicates noninfected mice. The results were obtained in 1 experiment that was representative of 2 experiments performed using 5 mice per group at each time point.

The number of infected cells at the site of infection was equal in WT and IFN-γ−/− mice until 8 weeks postinfection

We hypothesized that the differences in the inflammatory infiltrate in the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice might compensate for the absence of iNOS expression in the latter. It was possible that the infiltrate into the lesions of the WT mice was more efficient in parasite killing. However, because there were more macrophages at 8 weeks postinfection and therefore more potential host cells, these macrophages could also support the growth of more parasites.

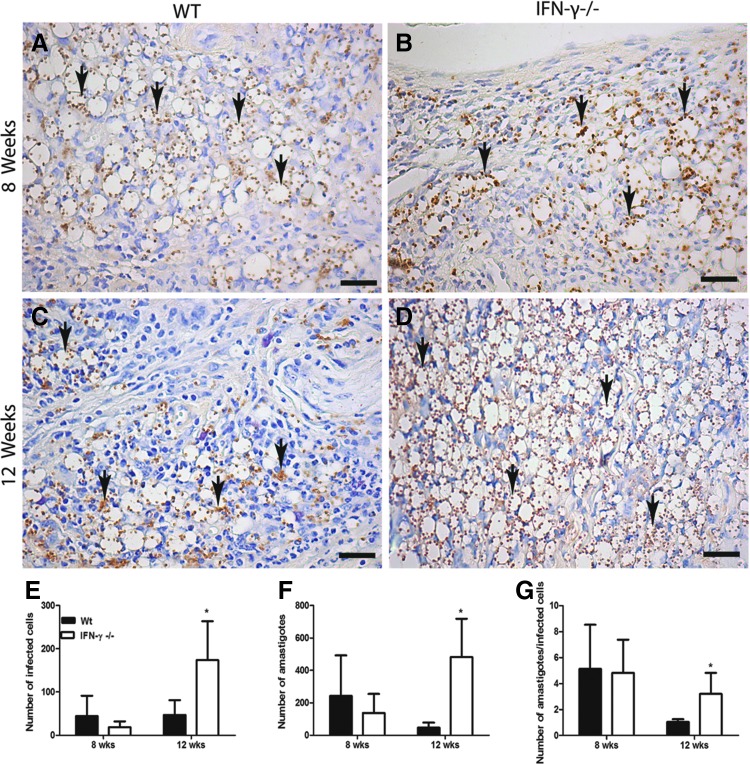

To investigate this hypothesis, we used immunohistochemistry to evaluate the number of infected cells in the footpads at 8 and 12 weeks postinfection. Interestingly, at 8 weeks postinfection, we found the same number of infected cells in both of the groups (Fig. 8A, B, E) as well as the same number of parasites in these groups (Fig. 8F), as was previously shown (Fig. 1B). In addition, the number of amastigotes per cell in both groups was also similar (Fig. 8G). In contrast, at 12 weeks postinfection, the IFN-γ−/− mice had more infected cells and more parasites per cell compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 8C, D, F, G).

FIG. 8.

Immunohistochemical analysis of L. amazonensis in WT (A, C) and IFN-γ−/− (B, D) mice after s.c. infection of the right footpad with 105 promastigotes. The mice were euthanized at 8 weeks (A, B) and 12 weeks (C, D) postinfection. Bars=8 μm. The arrows indicate the presence of amastigotes. The number of infected cells (E) and amastigotes (F) and the number of amastigotes per cell (G) were quantified using KS300 software. * Indicates significant differences between the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

IFN-γ-dependent recruitment of CD4+ T cells is pathogenic for the host during L. amazonensis infection

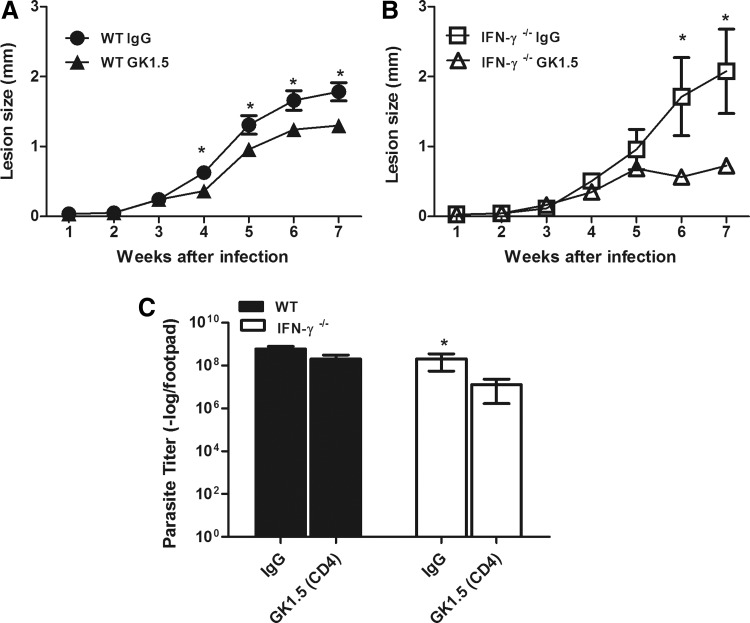

The presence of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at the site of infection was previously described as a pathogenic factor for the host during L. amazonensis infection (Soong and others 1997). Because we found an earlier migration of those cells to the site of infection in WT mice than in IFN-γ−/− mice, we examined whether this earlier migration affected the outcome of the disease.

When we depleted their CD8+ T cells, we did not find any difference in the pattern of lesion development or the size of the parasite burden at 7 weeks postinfection in these 2 groups of mice (data not shown). In contrast, the depletion of CD4+ T cells in the WT mice led to a decrease in the lesion size from 4 weeks postinfection (Fig. 9A). No differences in the parasite loads between CD4+ T-cell-depleted and rat IgG-treated WT mice (Fig. 9C) were found at 7 weeks postinfection. The CD4+ T-cell depletion in IFN-γ−/− mice also changed the course of their infection. After 6 weeks postinfection, we found smaller lesions in the CD4+ T-cell-depleted IFN-γ−/− mice (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, the CD4+ T-cell-depleted IFN-γ−/− mice had a decreased number of parasites at 7 weeks postinfection (Fig. 9C). Taken together, our data indicated that the early IFN-γ-dependent recruitment of CD4+ T cells to the lesion site appeared to be pathogenic to the host during L. amazonensis infection.

FIG. 9.

Course of infection after the depletion of CD4+ T cells in WT (A) and IFN-γ−/− (B) mice after s.c. infection of the right hind footpad with 105 promastigotes of L. amazonensis. The sizes of the lesions were measured weekly and were expressed as the increase in the footpad thickness. The number of parasites in the lesions was determined using limiting dilution analysis (C). The groups were treated with the GK1.5 antibody or with pure rat IgG as described in the Materials and Methods section. * Indicates significant differences between depleted or control WT or IFN-γ−/− mice (P<0.05). The data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

A noncanonical role for IFN-γ during L. amazonensis infection has been described. IFN-γ stimulation in vitro was shown to favor amastigote proliferation rather than parasite killing by macrophages (Qi and others 2004). The authors suggested that the IFN-γ-dependent CAT-2B expression by macrophages associated with the poor expression of iNOS and arginase I led to the accumulation of l-arginine, which is a growth factor for the parasite, in the host cells (Wanasen and others 2007). In addition, IFN-γ was not required for protection during the first few weeks postinfection with L. amazonensis in vivo (Pinheiro and Rossi-Bergmann 2007), and the administration of recombinant IFN-γ was not sufficient to induce protection from this parasite in BALB/c mice (Barral-Netto and others 1996). Moreover, the induction of a stronger level of Th1 polarization in a vaccine-treated experimental model (Carneiro and others 2014) or in IL-10-deficient mice (Jones and others 2002) failed to reverse their susceptibility to this parasite.

In the present study, we showed that IFN-γ was not required for protection until 8 weeks after infection because WT and IFN-γ−/− mice had lesions of a similar size and a similar parasite load until this time point. The late protective immunity might be related, at least in part, to a delay in IFN-γ production at the site of infection because we found increased levels of IFN-γ from 8 weeks postinfection. Although the in vitro restimulated lymph node cells responded to the L. amazonensis antigen by producing IFN-γ from the first week postinfection, the levels of IFN-γ increased substantially from week 8 postinfection at the site of infection. IFN-γ is an important inducer of iNOS expression in WT mice during the early weeks postinfection. As shown in the iNOS-deficient mice, iNOS expression is essential to the containment of parasite replication, as expected (Green and others 1990).

Because the IFN-γ−/− mice did not express iNOS, we expected that they utilized an alternative mechanism to control parasite growth that could compensate for the absence of iNOS, resulting in the same degree of disease development as that of WT mice until 8 weeks postinfection. Because IFN-γ is an important inducer of the expression of an NADPH oxidase component (Cassatella and others 1990), we also examined the level of ROS production in macrophages infected in vitro with the amastigote form of L. amazonensis and we observed a greater level of ROS production by WT cells compared with that of IFN-γ−/− cells (data not shown).

On the other hand, arginase I is a growth factor for Leishmania (Iniesta and others 2005; Kropf and others 2005) and therefore increased levels of arginase activity in the WT mice could explain the similarities in the pattern of lesion development in these 2 groups up to the eighth week postinfection. However, differences in the level of arginase activity of the 2 groups were detected only after 12 weeks postinfection. At this point, the higher level of arginase activity might have been related to the greater number of parasites that we found in the lesions of IFN-γ−/− mice.

It is important to highlight that the WT mice displayed a bias toward a proinflammatory profile of cytokine production from the early weeks postinfection compared with that of the IFN-γ−/− mice. The WT mice showed IFN-γ production, which was accompanied by a higher level of TNF-α and IL-1β production in the lesions. These cytokines are important in inducing parasite killing in macrophages through the induction of iNOS expression (Bogdan and others 1990; Lima-Junior and others 2013). Conversely, the levels of IL-10 and TGF-β (data not show), cytokines that could inhibit NO production in macrophages even after their activation by IFN-γ (Barral-Netto and others 1992; Vieth and others 1994; Vodovotz and others 1996; Ito and others 1999), were the same in both groups until 8 weeks postinfection. However, IL-10 is essential for parasite replication during L. amazonensis infection (Kane and Mosser 2001) and is involved in the regulation of inflammation, and consequently in the control of lesion development (Rubtsov and others 2008; Sousa and others 2014).

Therefore, the partial control of the lesion size in the WT mice at the later time points of infection could be related, at least in part, to their higher level of IL-10 production. The higher level of IL-4 expression in the IFN-γ−/− mice infected by L. major explained their susceptibility from the early time points (Wang and others 1994). In this study, low levels of IL-4 production in response to L. amazonensis infection were observed, and we found more IL-4 in the deficient mice only after 8 weeks postinfection. Hence, the similar numbers of parasites and lesion sizes in the WT and IFN-γ−/− mice could not be explained by the patterns of cytokine production in the lesions observed at the early time points postinfection.

We believe that the differences in the contents of the cellular infiltrates might account for the similarities in the course of infection observed in both groups. Infiltration of lesions by T cells has been reported to be pathogenic for the host during L. amazonensis infection (Soong and others 1997; Ji and others 2002).

At 8 weeks postinfection, we found more CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lesions of the WT mice compared with those of the IFN-γ−/− mice. The earlier migration of these cell types into the lesions of the WT mice can be explained by IFN-γ inducing the expression of chemokines. We demonstrated that there were higher levels of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCR3 expression in the presence of IFN-γ both in vitro and in vivo. These chemokines are required for the proper recruitment of lymphocytes to damaged sites (Taub and others 1993b; Liao and others 1995; Marfaing-Koka and others 1995).

In addition, at 8 weeks postinfection, more macrophages were found at the site of infection in the WT mice than in the IFN-γ−/− mice, which can be explained by the increased level of MCP-1 observed in the former group (Rollins and others 1990). Interestingly, at 12 weeks postinfection, we found the opposite, which was a greater number of T cells and macrophages in the lesions of the IFN-γ-deficient mice associated with a greater number of parasites and larger lesions compared with those of WT mice. We suggest that the differences in contents of the cellular infiltrate could compensate, during the early weeks after infection, for the lack of effector mechanisms in the IFN-γ−/− mice. Although at 8 weeks postinfection the WT mice showed an increased level of iNOS, they also had an increased number of macrophages in their lesions compared with those of the IFN-γ−/− mice.

We showed using immunohistochemical analysis that both groups had the same number of infected cells at this time point. Accordingly, the WT mice most likely could kill more parasites than could IFN-γ−/− mice, but because the former had more host cells to support parasite growth, in the end, both groups showed the same number of parasites in the lesions. In addition, the depletion of CD4+ T cells in the WT mice reduced the size of their lesions from 4 weeks postinfection. In contrast, this effect was observed in the IFN-γ−/− mice only after 6 weeks postinfection.

Thus, the earlier IFN-γ-dependent recruitment of CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells (data not shown), appeared to be pathogenic to the host and to contribute to lesion development, but not to parasite replication. The slight reduction in the parasite burden of the IFN-γ−/− mice could be related to the fact that we most likely depleted mainly Th2 T cells in those mice. IFN-γ has previously been described as playing a pathogenic role during parasite infection. The development of murine cerebral malaria appeared to be IFN-γ dependent because IFN-γ receptor-deficient mice did not experience this pathogenesis (Rudin and others 1997). Moreover, the migration of CD8+ T cells to the brain in a process that depended upon the expression of CXCR3, CXCL10, and CXCL9, which is IFN-γ dependent, was observed in this disease (Campanella and others 2008; Miu and others 2008; Claser and others 2011). Additionally, during Streptococcus pneumonia infection, IFN-γ−/− mice exhibited fewer bacteria and fewer monocytes within the brain than did WT mice (Mitchell and others 2012).

We demonstrated that IFN-γ plays paradoxical roles during L. amazonensis infection. IFN-γ is essential for the activation of an effector mechanism of resistance through the induction of iNOS expression, which induces parasite killing. In contrast, IFN-γ is also an important inducer of chemokine expression, mainly that of MCP-1, CXCL9, CXCL10, and the receptor CXCR3, which favor the migration of CD4+ T cells and macrophages to the lesion sites. CD4+ T cells are important for the development of lesions, whereas macrophages are the host cells for parasite replication. The dual effect of IFN-γ described in this study indicates the need to carefully evaluate the roles of this cytokine when testing vaccines and drugs developed to protect against L. amazonensis. Our data may also facilitate understanding why, even when strong Th1 polarization was induced in experimental vaccine models, this response was not sufficient to provide full protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Mr. Antonio Mesquita Vaz for expert animal care. This study was supported by FAPEMIG grant numbers, CDS—RED-00013-14 and BPD-00068-14, and CNPq grant numbers, 485431/2007-6 and 304588/2013-0. MBHC, M.E.M.L., L.M.A.S., L.M.S., R.G., W.L.T., and L.Q.V. are CNPq fellows. The authors are members of the INCT de Processos Redox em Biomedicina-Redoxoma (FAPESP/CNPq/CAPES, proc. 573530/2008-4) and NIDR (Network for infectious disease research–FAPEMIG).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Afonso LC, Scott P. 1993. Immune responses associated with susceptibility of C57BL/10 mice to Leishmania amazonensis. Infect Immun 7(61):2952–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den BM. 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 5(7):e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral A, Pedral-Sampaio D, Grimaldi JG, Momen H, McMahon-Pratt D, Ribeiro de JA, Almeida R, Badaro R, Barral-Netto M, Carvalho EM. 1991. Leishmaniasis in Bahia, Brazil: evidence that Leishmania amazonensis produces a wide spectrum of clinical disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 5(44):536–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral-Netto M, Barral A, Brownell CE, Skeiky YA, Ellingsworth LR, Twardzik DR, Reed SG. 1992. Transforming growth factor-beta in leishmanial infection: a parasite escape mechanism. Science 5069(257):545–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral-Netto M, Von Sohsten RL, Teixeira M, dos Santos WL, Pompeu ML, Moreira RA, Oliveira JT, Cavada BS, Falcoff E, Barral A. 1996. In vivo protective effect of the lectin from Canavalia brasiliensis on BALB/c mice infected by Leishmania amazonensis. Acta Trop 4(60):237–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers C, Honey K, Fink S, Forbush K, Rudensky A. 2003. Differential regulation of cathepsin S and cathepsin L in interferon gamma-treated macrophages. J Exp Med 2(197):169–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belosevic M, Finbloom DS, Van Der Meide PH, Slayter MV, Nacy CA. 1989. Administration of monoclonal anti-IFN-gamma antibodies in vivo abrogates natural resistance of C3H/HeN mice to infection with Leishmania major. J Immunol 1(143):266–274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan C, Moll H, Solbach W, Rollinghoff M. 1990. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in combination with interferon-gamma, but not with interleukin 4 activates murine macrophages for elimination of Leishmania major amastigotes. Eur J Immunol 5(20):1131–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier NA, Schreiber RD. 1985. Requirement of endogenous interferon-gamma production for resolution of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 21(82):7404–7408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella GS, Tager AM, El Khoury JK, Thomas SY, Abrazinski TA, Manice LA, Colvin RA, Luster AD. 2008. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 are required for the development of murine cerebral malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 12(105):4814–4819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro MB, de Andrade E, Sousa LM, Vaz LG, Santos LM, Vilela L, de Souza CC, Goncalves R, Tafuri WL, Afonso LC, Cortes DF, Vieira LQ. 2014. Short term protection conferred by Leishvacin(R) against experimental Leishmania amazonensis infection in C57BL/6 mice. Parasitol Int 63(6):826–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella MA, Bazzoni F, Flynn RM, Dusi S, Trinchieri G, Rossi F. 1990. Molecular basis of interferon-gamma and lipopolysaccharide enhancement of phagocyte respiratory burst capability. Studies on the gene expression of several NADPH oxidase components. J Biol Chem 33(265):20241–20246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain R, Varkila K, Coffman RL. 1992. IL-4 induces a Th2 response in Leishmania major-infected mice. J Immunol 4(148):1182–1187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claser C, Malleret B, Gun SY, Wong AY, Chang ZW, Teo P, See PC, Howland SW, Ginhoux F, Renia L. 2011. CD8+ T cells and IFN-gamma mediate the time-dependent accumulation of infected red blood cells in deep organs during experimental cerebral malaria. PLoS One 4(6):e18720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes DF, Carneiro MB, Santos LM, Souza TC, Maioli TU, Duz AL, Ramos-Jorge ML, Afonso LC, Carneiro C, Vieira LQ. 2010. Low and high-dose intradermal infection with Leishmania major and Leishmania amazonensis in C57BL/6 mice. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 6(105):736–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer LA, Klemsz MJ. 1997. Altered kinetics of Tap-1 gene expression in macrophages following stimulation with both IFN-gamma and LPS. Cell Immunol 1(178):53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JP, Zhang X, Frauwirth KA, Mosser DM. 2006. Biochemical and functional characterization of three activated macrophage populations. J Leukoc Biol 6(80):1298–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes CT, Costa VV, Cisalpino D, Amaral FA, Souza PR, Souza RS, Ryffel B, Vieira LQ, Silva TA, Atrasheuskaya A, Ignatyev G, Sousa LP, Souza DG, Teixeira MM. 2011. IFN-gamma production depends on IL-12 and IL-18 combined action and mediates host resistance to dengue virus infection in a nitric oxide-dependent manner. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(5):e1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo F, Koerner TJ, Adams DO. 1989. Molecular mechanisms regulating the expression of class II histocompatibility molecules on macrophages. Effects of inductive and suppressive signals on gene transcription. J Immunol 11(143):3781–3786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med 6(178):2249–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski TF, Fitch FW. 1988. Anti-proliferative effect of IFN-gamma in immune regulation. I. IFN-gamma inhibits the proliferation of Th2 but not Th1 murine helper T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol 12(140):4245–4252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SJ, Meltzer MS, Hibbs JB, Jr., Nacy CA. 1990. Activated macrophages destroy intracellular Leishmania major amastigotes by an L-arginine-dependent killing mechanism. J Immunol 1(144):278–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel FP, Schoenhaut DS, Rerko RM, Rosser LE, Gately MK. 1993. Recombinant interleukin 12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med 5(177):1505–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta V, Carcelen J, Molano I, Peixoto PM, Redondo E, Parra P, Mangas M, Monroy I, Campo ML, Nieto CG, Corraliza I. 2005. Arginase I induction during Leishmania major infection mediates the development of disease. Infect Immun 9(73):6085–6090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniesta V, Gomez-Nieto LC, Molano I, Mohedano A, Carcelen J, Miron C, Alonso C, Corraliza I. 2002. Arginase I induction in macrophages, triggered by Th2-type cytokines, supports the growth of intracellular Leishmania parasites. Parasite Immunol 3(24):113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Ansari P, Sakatsume M, Dickensheets H, Vazquez N, Donnelly RP, Larner AC, Finbloom DS. 1999. Interleukin-10 inhibits expression of both interferon alpha- and interferon gamma- induced genes by suppressing tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1. Blood 5(93):1456–1463 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Sun J, Qi H, Soong L. 2002. Analysis of T helper cell responses during infection with Leishmania amazonensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 4(66):338–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DE, Ackermann MR, Wille U, Hunter CA, Scott P. 2002. Early enhanced Th1 response after Leishmania amazonensis infection of C57BL/6 interleukin-10-deficient mice does not lead to resolution of infection. Infect Immun 4(70):2151–2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MM, Mosser DM. 2001. The role of IL-10 in promoting disease progression in leishmaniasis. J Immunol 2(166):1141–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf P, Fuentes JM, Fahnrich E, Arpa L, Herath S, Weber V, Soler G, Celada A, Modolell M, Muller I. 2005. Arginase and polyamine synthesis are key factors in the regulation of experimental leishmaniasis in vivo. FASEB J 8(19):1000–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao F, Rabin RL, Yannelli JR, Koniaris LG, Vanguri P, Farber JM. 1995. Human Mig chemokine: biochemical and functional characterization. J Exp Med 5(182):1301–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima-Junior DS, Costa DL, Carregaro V, Cunha LD, Silva AL, Mineo TW, Gutierrez FR, Bellio M, Bortoluci KR, Flavell RA, Bozza MT, Silva JS, Zamboni DS. 2013. Inflammasome-derived IL-1beta production induces nitric oxide-mediated resistance to Leishmania. Nat Med 7(19):909–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfaing-Koka A, Devergne O, Gorgone G, Portier A, Schall TJ, Galanaud P, Emilie D. 1995. Regulation of the production of the RANTES chemokine by endothelial cells. Synergistic induction by IFN-gamma plus TNF-alpha and inhibition by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol 4(154):1870–1878 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Yau B, McQuillan JA, Ball HJ, Too LK, Abtin A, Hertzog P, Leib SL, Jones CA, Gerega SK, Weninger W, Hunt NH. 2012. Inflammasome-dependent IFN-gamma drives pathogenesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. J Immunol 10(189):4970–4980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miu J, Mitchell AJ, Muller M, Carter SL, Manders PM, McQuillan JA, Saunders BM, Ball HJ, Lu B, Campbell IL, Hunt NH. 2008. Chemokine gene expression during fatal murine cerebral malaria and protection due to CXCR3 deficiency. J Immunol 2(180):1217–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. 1986. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol 7(136):2348–2357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro RO, Rossi-Bergmann B. 2007. Interferon-gamma is required for the late but not early control of Leishmania amazonensis infection in C57Bl/6 mice. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1(102):79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Ji J, Wanasen N, Soong L. 2004. Enhanced replication of Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes in gamma interferon-stimulated murine macrophages: implications for the pathogenesis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun 2(72):988–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BJ, Yoshimura T, Leonard EJ, Pober JS. 1990. Cytokine-activated human endothelial cells synthesize and secrete a monocyte chemoattractant, MCP-1/JE. Am J Pathol 6(136):1229–1233 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, Treuting P, Siewe L, Roers A, Henderson WR, Jr., Muller W, Rudensky AY. 2008. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity 4(28):546–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin W, Favre N, Bordmann G, Ryffel B. 1997. Interferon-gamma is essential for the development of cerebral malaria. Eur J Immunol 4(27):810–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks D, Noben-Trauth N. 2002. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to Leishmania major in mice. Nat Rev Immunol 11(2):845–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadick MD, Heinzel FP, Holaday BJ, Pu RT, Dawkins RS, Locksley RM. 1990. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon gamma-independent mechanism. J Exp Med 1(171):115–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira FT, Lainson R, Corbett CE. 2004. Clinical and immunopathological spectrum of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with special reference to the disease in Amazonian Brazil: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 3(99):239–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong L, Chang CH, Sun J, Longley BJ, Jr., Ruddle NH, Flavell RA, McMahon-Pratt D. 1997. Role of CD4+ T cells in pathogenesis associated with Leishmania amazonensis infection. J Immunol 11(158):5374–5383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa LM, Carneiro MB, Resende ME, Martins LS, Dos Santos LM, Vaz LG, Mello PS, Mosser DM, Oliveira MA, Vieira LQ. 2014. Neutrophils have a protective role during early stages of Leishmania amazonensis infection in BALB/c mice. Parasite Immunol 1(36):13–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MM, Tam MF, Wolf SF, Sher A. 1995. IL-12-induced protection against blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS requires IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha and occurs via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. J Immunol 5(155):2545–2556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Schreiber RD, Remington JS. 1988. Interferon-gamma: the major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science 4851(240):516–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafuri WL, Santos RL, Arantes RM, Goncalves R, de Melo MN, Michalick MS, Tafuri WL. 2004. An alternative immunohistochemical method for detecting Leishmania amastigotes in paraffin-embedded canine tissues. J Immunol Methods 1–2(292):17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub DD, Conlon K, Lloyd AR, Oppenheim JJ, Kelvin DJ. 1993a. Preferential migration of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to MIP-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta. Science 5106(260):355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub DD, Lloyd AR, Conlon K, Wang JM, Ortaldo JR, Harada A, Matsushima K, Kelvin DJ, Oppenheim JJ. 1993b. Recombinant human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med 6(177):1809–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrico F, Heremans H, Rivera MT, Van ME, Billiau A, Carlier Y. 1991. Endogenous IFN-gamma is required for resistance to acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Immunol 10(146):3626–3632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieth M, Will A, Schroppel K, Rollinghoff M, Gessner A. 1994. Interleukin-10 inhibits antimicrobial activity against Leishmania major in murine macrophages. Scand J Immunol 4(40):403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Geiser AG, Chesler L, Letterio JJ, Campbell A, Lucia MS, Sporn MB, Roberts AB. 1996. Spontaneously increased production of nitric oxide and aberrant expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase in vivo in the transforming growth factor beta 1 null mouse. J Exp Med 5(183):2337–2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanasen N, MacLeod CL, Ellies LG, Soong L. 2007. L-arginine and cationic amino acid transporter 2B regulate growth and survival of Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes in macrophages. Infect Immun 6(75):2802–2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZE, Reiner SL, Zheng S, Dalton DK, Locksley RM. 1994. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon gamma-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med 4(179):1367–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Koide Y, Uchijima M, Yoshida TO. 1994. IFN-gamma induces IL-12 mRNA expression by a murine macrophage cell line, J774. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 3(198):857–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]