Abstract

As the population ages, more adults will develop impaired decision-making capacity and have no family members or friends available to make medical decisions on their behalf. In such situations, a professional guardian is often appointed by the court. This is an official who has no pre-existing relationship with the impaired individual but is paid to serve as a surrogate decision-maker. When a professional guardian is faced with decisions concerning life-sustaining treatment, substituted judgment may be impossible, and reports have repeatedly suggested that guardians are reluctant to make the decision to limit care.

Clinicians are well positioned to assist guardians with these decisions and safeguard the rights of the vulnerable persons they represent. Doing so effectively requires knowledge of the laws governing end-of-life decisions by guardians. Clinicians, however, are often uncertain about whether guardians are empowered to withhold treatment and when their decisions require judicial review. To address this issue, we analyzed state guardianship statutes and reviewed recent legal cases in order to characterize the authority of a guardian over choices about end-of-life treatment. We found that a large majority of state guardianship statutes have no language about end-of-life decisions and identified just five legal cases over the past decade that addressed a guardian’s authority over these decisions, with only one case providing a broad framework applicable to clinical practice. Work to improve end-of-life decision-making by guardians may benefit from a multi-disciplinary effort to develop comprehensive standards that can guide clinicians and guardians when treatment decisions need to be made.

Introduction

Many older persons will develop impaired capacity to make medical decisions and will need assistance from a surrogate decision-maker.1 A patient may appoint a surrogate decision-maker before losing capacity, and most states have laws allowing a default surrogate to be selected from an individual’s family members.2 For some incapacitated persons, health care decisions are made by a guardian, also called a guardian or conservator of person – a surrogate decision-maker appointed by a judge.3

One and a half million adults are thought to be under guardianship in the U.S.4 In many instances, the guardian is a family member or friend of the impaired individual. In approximately 25% of cases, however, the guardian is an organization or paid official with no knowledge of the impaired individual prior to appointment.5,6 In our work, we refer to this as a professional guardian. The number of persons with professional guardians is expected to rise dramatically as the population ages and more individuals are incapacitated from dementia.4,7

Professional guardians face unique challenges when making decisions for persons with serious illness. Because they have no prior relationship with the individuals they represent, it may be impossible for professional guardians to exercise substituted judgment, which involves reflecting on a person’s values to determine what care the person would have wanted. Substituted judgment is particularly important for decisions near the end of life, since preferences vary widely and change over time.8,9 When substituted judgment is impossible, surrogate decision-makers may rely on a best interests standard, making decisions from the perspective of a generic, reasonable person after weighing a treatment’s benefits and burdens.10 For professional guardians, who do not always have training in medical decision-making and are often busy with large caseloads,11 this process, too, may be difficult.

When they cannot ascertain a patient’s preferences and face the ethical challenges involved in assessing a person’s best interests, guardians may be reluctant to give orders limiting treatment. Reports have long suggested that they choose instead the “safer” path of aggressive care by default or defer to a cumbersome judicial process.12–17 Physicians are in a unique position to assist guardians with these difficult decisions and to collaborate with them to protect the rights and dignity of the vulnerable persons they represent. Doing so, however, requires knowledge of the laws governing guardians, particularly those concerning what decisions a guardian is allowed to make and when judicial review is required. Since there is uncertainty among clinicians about these issues, we sought to understand current laws concerning end-of-life decision-making by professional guardians. We analyzed guardianship statutes and reviewed recent legal cases to characterize the authority of a guardian when choices about life-sustaining treatment must be made.

Methods

Two primary data sources were used: the guardianship statutes in all U.S. states and the District of Columbia, and case law pertaining to guardians and end-of-life decisions since 2004.

Data on Guardianship Statutes

We used two studies of guardianship to identify state guardianship statutes18,19 and retrieved them in August 2014 using Westlaw, a legal research database. We reviewed statutes for language about a guardian’s ability to make end-of-life decisions and circumstances under which these decisions require court approval. Statutes were placed into one of three groups: (1) contains no language about end-of-life decisions; (2) prohibits guardians from making end-of-life decisions without court approval; (3) permits guardians to make end-of-life decisions independently. Some states have statutes that both prohibit and permit independent decisions, depending on the circumstances. Statutes stating that independent end-of-life decisions are impermissible except under certain circumstances were put in the “prohibits” group and exceptions were noted. Statutes allowing independent end-of-life decisions except under certain circumstances were placed in the “permits” group and exceptions were noted. For every statute, we also noted references to broad decision-making standards to be used by guardians (substituted judgment, best interests, substituted judgment and then best interests, or no standard).

Identification of Legal Cases

To identify legal cases concerning a guardian’s authority over end-of-life decisions, we reviewed annual summaries of case law published by the National Guardianship Association from 2004–2013. We then searched Westlaw for decisions since 2004 that included any form of the words guardian or conservator and any combination of the words end, life, and decision in the same sentence. Two investigators (AC and MW) reviewed cases identified by this process. Cases involving minors or individuals with developmental disabilities were excluded, since different standards of judicial oversight often apply. Cases were also excluded if a guardian’s authority in end-of-life decisions was not discussed. For the remaining cases, the relevant legal issues were summarized.

Results

State Guardianship Statutes

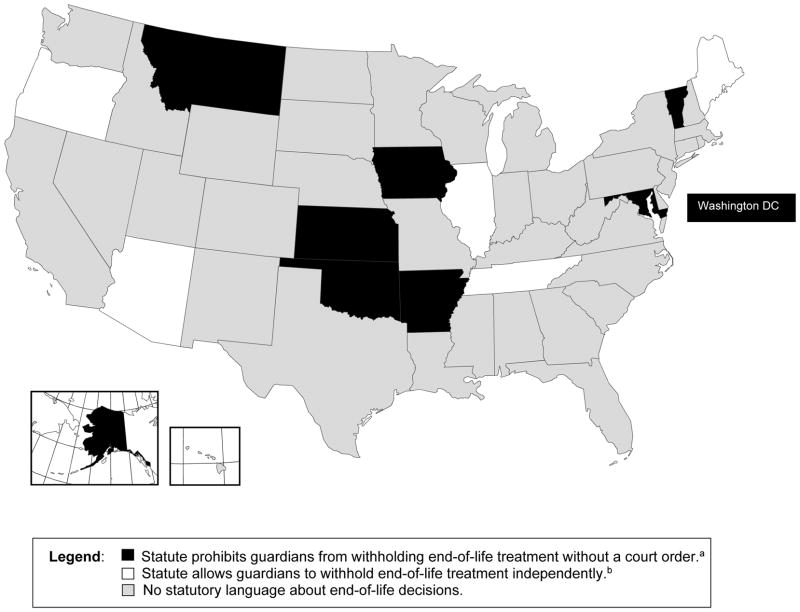

The Figure summarizes state laws regarding guardians and end-of-life decisions. In 37 states, the guardianship statute contains no specific language about a guardian’s authority to make end-of-life decisions. In 16 of these states (see Appendix), the statute does not reference a decision-making standard for the guardian to use in medical decisions overall.

Figure. Instructions about End-of-Life Decisions in State Guardianship Statutes.

Each state and the District of Columbia was placed into one of three groups: (1) statute contains no language about end-of-life decisions (shown in grey); (2) statute prohibits a guardian from making end-of-life decisions without court approval (shown in black); or (3) statute permits a guardian to make end-of-life decisions independently (shown in white). Exceptions to these laws are noted.

aExceptions exist in statutes in Alaska, Kansas, Montana, Oklahoma, and Vermont.

bExceptions exist in all statutes.

The statutes in eight states and the District of Columbia prohibit a guardian from making end-of-life decisions without judicial review. Of these laws, five of nine contain exceptions that expand a guardian’s authority under certain circumstances. In Kansas, Montana, Oklahoma, and Vermont, a guardian may consent to the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment if an advance directive provides evidence of prior wishes. Guardians in Vermont, additionally, need not seek approval for do-not-resuscitate orders in emergencies.20 In Alaska, a guardian “may not … consent … to the withholding of lifesaving medical procedures” but “is not required to oppose the cessation or withholding of lifesaving medical procedures when those procedures will serve only to prolong the dying process.”21

Five states have statutes allowing guardians to make end-of-life decisions independently. In each law, there are contingencies. Oregon’s statute details specific situations in which artificial nutrition may be withheld by a guardian.22 Maine requires a guardian to seek judicial approval if “the guardian’s decision is made against the advice of the ward’s primary physician and in the absence of instructions from the ward made while the ward had capacity.”23 In Tennessee and Arizona, the court must explicitly empower the guardian to make end-of-life decisions in the guardianship order.24,25 Illinois’s law references a separate statute, its Health Care Surrogate Act, and requires court involvement if that law’s requirements, including documentation of a qualifying terminal or irreversible condition, cannot be met.26

Legal Cases

Our initial search identified 41 cases involving end-of-life decisions by a court-appointed guardian. We excluded 23 cases involving minors and individuals with developmental disabilities and 13 cases in which a guardian’s authority in end-of-life decisions was not discussed. Five cases remained.

In two cases, courts affirmed that a guardian with evidence of a patient’s preferences can request that tube feeding be discontinued.27,28 Neither court discussed situations in which decisions about life-sustaining treatment are needed and substituted judgment is impossible.

Two cases addressed the obligation of guardians to make end-of-life decisions. Courts in different states reached different conclusions. A Florida court, hearing an appeal concerning the care of Theresa Schiavo,29 accepted the responsibility “to make the decision to continue or discontinue life-sustaining procedures.”30 The court stated that “courts remain open to make these decisions … when family members cannot agree or when a guardian believes it would be more appropriate for a neutral judge to make the decision.”31 The Alaska Supreme Court, however, concluded that a guardian cannot simply decide “not [to] make end-of-life decisions,” even though “a guardian may not want the responsibility.”32

In one case, a guardian faced a choice about life-sustaining treatment in a state without specific statutory guidance. Lower courts disagreed about whether guardians could make such decisions without judicial review. The issue was taken up the state Supreme Court. In re Guardianship of Tschumy involved a man in Minnesota who suffered from schizophrenia and required a professional guardian to make medical decisions. He suffered anoxic brain injury. The hospital caring for him petitioned the court to authorize his guardian to order the removal of life support. The court complied and Mr. Tschumy died. His guardian, however, argued that judicial involvement had been unnecessary because a guardian’s ability to consent for medical care includes the authority to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. The district court disagreed and held that this ability “is not inherent in any of the enumerated powers normally granted a guardian.”33 On appeal, the decision was reversed. The appellate court was concerned that “imposing a requirement for additional court involvement” would be inconsistent with “a private, medically based model of decisionmaking.”34 The Minnesota Supreme Court affirmed the appellate ruling. The majority raised the possibility of “extended suffering” if guardians were required to seek judicial review and held that “a guardian given the medical-consent power … has the authority to authorize removal of a ward’s life-sustaining treatment, without court approval, when all interested parties agree that removal is in the ward’s best interest.”35

Discussion

The guardianship statutes in most states do not establish whether a guardian may make end-of-life decisions for an incapacitated person or provide a framework for determining when judicial oversight is required. In 13 states and the District of Columbia, there is specific language about end-of-life decisions, but 10 of 14 of these laws contain complex exceptions that expand or contract a guardian’s authority. Recent case law is scant. Only one case over the past decade, Tschumy, provided guidance for the situation commonly encountered in practice, when decisions about life-sustaining treatment need to be made for an impaired individual whose preferences are not known, and neither the guardian nor the medical team is certain who possesses the authority to make these decisions or what process must be followed.

These findings extend the results of previous work that has found variable laws governing other aspects of surrogate decision-making. A study comparing the authority of a patient’s next of kin to that of a legally-designated health care proxy found that rules and decision-making standards differed substantially between states.36 Other work has found significant differences in state rules concerning advance care planning.2 Our results, showing that laws governing professional guardians and end-of-life decisions are inconsistent and incomplete, add to the evidence that the legal approach to decision-making for incapacitated persons in the U.S. is far from uniform.

Surrogate decision-makers grapple with complex ethical and spiritual concerns involving an individual’s interests and dignity.37 The differences in state statutes and lack of instructions in most states may provide an excuse for professional guardians to avoid these difficult issues by putting key decisions in the hands of judges, who are furthest from the incapacitated person and have varying experience with end-of-life care.38 The absence of clear standards is also likely to encourage the development of institution-specific practices. One professional guardian testified in the Tschumy case that “he has been at hospitals where one hospital says he has the right and other hospitals say he does not have the right [to make] end-of-life decisions.”39 These issues make it exceedingly difficult for physicians to work effectively with guardians to ensure that high-quality end-of-life decisions are made.

Despite the variation in state laws, the same considerations arise wherever life-sustaining treatment is contemplated for an incapacitated person who is represented by a guardian. There is a need for consistent decision-making standards. The incompleteness of guardianship statutes and small number of recent court decisions suggest that agreement around such standards is unlikely to emerge spontaneously among lawmakers in different states or from the process of bringing cases to courts. Moreover, given the complexity of end-of-life decisions, it could be argued that standards for guardians and physicians ought not solely be left to legislative or judicial processes. Rather, the development of guidelines may require leadership from physicians and other experts, including lawyers, bioethicists, and national guardianship organizations. Once developed, such guidelines could be used as a template by states and incorporated into their guardianship statutes. The success of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm provides a model by which consensus can be built around ethical and medico-legal issues and then lead to change on a state-by-state level.40

One approach would be to allow treating physicians to make decisions in an incapacitated patient’s best interests when the patient’s preferences are not known by the guardian. This commonly occurs when an impaired patient has no identifiable decision-maker at all, and it is recommended in some medical society guidelines.41–43 Since there is a potential conflict of interest when clinicians serve as surrogate decision-makers, an alternative would be to leave decisions to hospital ethics committees or to the voluntary surrogate decision-making panels in some states.44 Tools known as patient preference predictors, which use the modal preferences of similar patients to predict an incapacitated patient’s wishes, could supplement physicians’ or ethics committees’ assessments.45,46

Another approach would be to establish formal roles for physicians and guardians, who would collaborate to make these decisions. The treating physician would suggest a plan of care in the patient’s best interests and the guardian would ask clarifying questions, ensuring that all relevant perspectives were considered. Ethics committees might resolve disagreements, with courts involved as a last resort. This process resembles the procedure affirmed in the Tschumy decision and leverages the unique perspective of the guardian, who has an opportunity to develop a relationship with the impaired person, even if she can no longer express her preferences and values. The success of this approach would hinge on the availability of in-depth training for guardians to enable them work optimally with physicians. Given the additional resources required, one model to be considered might be the voluntary guardianship program developed in Indiana, in which qualified volunteers – including medical students and home health aides – were recruited to represent patients.47

This study has several limitations. We did not assess the role of court rules, which differ by jurisdiction and may provide guidance to professional guardians, or laws like health care surrogate and advance directive statutes than can interact with guardianship statutes in complex ways. We found fewer cases than we expected that discussed a guardian’s authority to make end-of-life decisions. Many decisions from state probate courts are not published and do not appear in searchable indices.48,49 We investigated methods for identifying additional cases but determined that visiting multiple courts and identifying guardianship proceedings among the issues handled by them was not feasible. To account for the evolution of guardianship law and rapid change around end-of-life issues, we limited our search to the past ten years and may have missed preexisting case law in some states. Nevertheless, the narrowness of most cases we identified, and small number of decisions overall, suggest that a more exhaustive review would likely not have found agreement or consistent guidance around the vexing issues that arise in practice.

In summary, most state laws do not define the authority of a professional guardian to make decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Because legal uncertainty and variation make these complex decisions even more difficult, ensuring appropriate end-of-life care for patients with professional guardians may require a multidisciplinary effort to develop and disseminate clear standards to guide physicians and guardians in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Erica Wood, JD, from the Committee on Law and Aging at the American Bar Association, for her comments on a draft of the manuscript.

Dr. Cohen had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/support: Dr. Cohen is supported by a grant from the Hartford Centers of Excellence National Program at Yale University, as well as a training grant from the National Institute on Aging (T32AG1934).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interests to disclose.

Contributions: Study concept and design: Cohen, Cooney, Fried.

Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: Cohen, Wright, Fried.

Drafting of the manuscript: Cohen.

Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors.

References

- 1.Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):370–377. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castillo LS, Williams BA, Hooper SM, Sabatino CP, Weithorn LA, Sudore RL. Lost in translation: the unintended consequences of advance directive law on clinical care. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):121–128. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terminology concerning guardianship is complex, varies by jurisdiction, and has changed over time. This article uses the term guardian to mean a guardian of person, who is charged with making decisions about the well-being of another, including health care decisions. The court may also appoint a guardian of estate to make decisions about an individual’s property. An individual can have either kind of guardian or both; these roles can be performed by the same person or by different people. In some states, the word conservator is used to mean guardian of estate, while in other states there are conservators of person and conservators of estate and the word guardian is used for minors and persons with intellectual disabilities.

- 4.Teaster P, Schmidt W, Wood E, Lawrence S, Mendiondo M. Public Guardianship after 25 Years: In the Best Interest of Incapacitated People? Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulcroft K, Kielkopf MR, Tripp K. Elderly wards and their legal guardians: analysis of county probate records in Ohio and Washington. Gerontologist. 1991;31(2):156–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teaster PB, Wood EF, Karp N, Lawrence SA, Schmidt WC, Jr, Mendiondo MS. [Accessed June 1, 2015];Wards of the State: A National Study of Public Guardianship. 2005 :58–94. http://apps.americanbar.org/aging/publications/docs/wardofstatefinal.pdf.

- 7.United States Senate Special Committee on Aging -- 108th Congress. Guardianship over the Elderly: Security Provided or Freedoms Denied? Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890–895. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.President’s Council on Bioethics. [Accessed June 1, 2015];Taking Care: Ethical Caregiving in Our Aging Society. 2005 :64–65. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559378/taking_care.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 11.Pope T, Sellers T. Legal briefing: The unbefriended: making healthcare decisions for patients without surrogates (Part 1) J Clin Ethics. 2011;23(1):84–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Report on the Ethical, Medical, and Legal Issues in Treatment Decisions. Vol. 147. Washington, DC: U S Government Printing Office; 1983. p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillick MR. Medical decision-making for the unbefriended nursing home resident. J Ethics Law Aging. 1(2):87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of Maryland Attorney General. [Accessed June 1, 2015];Policy Study on Alzheimer Disease Care. 2004 :31–37. http://www.oag.state.md.us/healthpol/alzheimers.htm.

- 15.Pope T. Making medical decisions for patients without surrogates. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):2013–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1308197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breznay J, Paris BC. Challenges of guardianship: examining four cases from New York State. Ann Long-Term Care. 2014;22(3):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hastings KB. Hardships of end-of-life care with court-appointed guardians. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):57–60. doi: 10.1177/1049909113481100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayton K. Standards for health care decision-making: legal and practical considerations. Utah L Rev. 2012:1329–1444. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandler K. A guardian’s health care decision-making authority: statutory restrictions. Bifocal. 2014;35(4):106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 3075 (West).

- 21.Alaska Stat. Ann. § 13.26.150 (West).

- 22.Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 125.315 (West).

- 23.Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 18-A, § 5-312 (West).

- 24.Tenn. Code Ann. § 34-3-107 (West).

- 25.Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 14-5303.

- 26.755 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. §5/11a-17 (West).

- 27.In Re Biersack, No. 10-04-03, 2004 WL 2785963 (Ohio Ct. App. Dec. 6, 2004).

- 28.In Re L.M.R., No. 4392-S-MG, 2008 WL 398999 (Del. Ch. Jan. 24, 2008).

- 29.Perry JE, Churchill LR, Kirshner HS. The Terri Schiavo case: Legal, ethical, and medical perspectives. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:744–748. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.In Re Guardianship of Schiavo, 792 So. 2d 551 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2001).

- 31.In Re Guardianship of Schiavo, 916 So. 2d 814 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2005).

- 32.P.C. v. Dr K. 187 P.3d 457 (Alaska 2008).

- 33.In Re the Guardianship of Jeffers J. Tschumy, Ward, No. 27-GC-PR-07-498 (Minn. Oct. 18, 2012)

- 34.In re Guardianship of Tschumy, 834 N.W.2d 764 (Minn. Ct. App. 2013), review granted (Oct. 15, 2013), affirmed, 853 N.W.2d 728 (Minn. 2014).

- 35.In re Guardianship of Tschumy. 853 N.W.2d 728 (Minn. 2014).

- 36.Venkat A, Becker J. The effect of statutory limitations on the authority of substitute decision makers on the care of patients in the intensive care unit: case examples and review of state laws affecting withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatment. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29(2):71–80. doi: 10.1177/0885066611433551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dworkin RM. Life’s Dominion: An Argument About Abortion, Euthanasia, and Individual Freedom. Vintage. 1993:179–242. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hafemeister TL. Guidelines for state court decision making in life-sustaining medical treatment cases. Issues Law Med. 1992;7(4):443–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.In re: The Guardianship and Conservatorship of Jeffers J. Tschumy, Ward. 2013 WL 7098349 (Minn. App.), 3.

- 40.Pope T, Hexum M. Legal Briefing: POLST: Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. J Clin Ethics. 2012;23(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Making treatment decisions for incapacitated older adults without advance directives. AGS Ethics Committee. American Geriatrics Society. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:986–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White DB, Curtis JR, Lo B, Luce JM. Decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for critically ill patients who lack both decision-making capacity and surrogate decision-makers. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2053–2059. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227654.38708.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White DB, Curtis JR, Wolf LE, et al. Life support for patients without a surrogate decision maker: Who decides? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:34–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood E, Karp N. Incapacitated and Alone: Health Care Decision-Making for the Unbefriended. 2003. pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smucker WD, Houts RM, Danks JH, Ditto PH, Fagerlin A, Coppola KM. Modal preferences predict elderly patients’ life-sustaining treatment choices as well as patients’ chosen surrogates do. Med Decis Making. 20:271–280. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0002000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rid A, Wendler D. Use of a patient preference predictor to help make medical decisions for incapacitated patients. J Med Philos. 2014;39:104–129. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bandy R, Sachs G, Montz K, Inger L, Bandy R, Torke A. Wishard Volunteer Advocates Program: an intervention for at-risk, incapacitated, unbefriended adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2171–2179. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerken JL. A librarian’s guide to unpublished judicial opinions. Law Libr J. 2004;96:475–501. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dow DR, McNeese BT. Invisible executions: a preliminary analysis of publication rates in death penalty cases in selected jurisdictions. Texas J Civ Lib Civ Rights. 2003;8:149–173. [Google Scholar]