Abstract

Adult daughters face distinct challenges caring for parents with dementia and may experience compassion fatigue: the combination of helplessness, hopelessness, an inability to be empathic, and a sense of isolation resulting from prolonged exposure to perceived suffering. Prior research on compassion fatigue has focused on professional healthcare providers and has overlooked filial caregivers. This study attempts to identify and explore risk factors for compassion fatigue in adult daughter caregivers and to substantiate further study of compassion fatigue in family caregivers. We used content analysis of baseline interviews with 12 adult daughter caregivers of a parent with dementia who participated in a randomized trial of homecare training. Four themes were identified in adult daughter caregiver interviews: (a) uncertainty; (b) doubt; (c) attachment; and (d) strain. Findings indicated adult daughter caregivers are at risk for compassion fatigue, supporting the need for a larger study exploring compassion fatigue in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Over 15.5 million caregivers for older adults with dementia in the USA provide an estimated 17.7 billion hours of care, which has been valued at more than US$220.2 billion in unreimbursed healthcare services (Alzheimer’s Association, 2014). Family caregivers are essential to the healthcare system, yet they reportedly experience negative psychological consequences, such as depression, anxiety, and stress as a consequence of providing care (Cooper, Katona, Orrell, & Livingston, 2008; Ott, Sanders, & Kelber, 2007; Schulz et al., 2008; Schumacher, Beck, & Marren, 2006; Simpson & Carter, 2013; Taylor, Ezell, Kuchibhatla, Ostbye, & Clipp, 2008). In addition, family members may feel resentful about the caregiving situation and might also feel helpless and hopeless regarding caregiving (Perry, Dalton, & Edwards, 2010). These feelings suggest the caregiver may be experiencing ‘compassion fatigue’. There are various definitions of compassion fatigue, the most common being an adverse consequence of caring for individuals in need (Adams, Figley, & Boscarino, 2008; Joinson, 1992; Keidel, 2002; Sabo, 2011). Prior research on compassion fatigue has focused on professional healthcare providers and overlooked filial caregivers.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore risk factors for compassion fatigue in adult daughter caregivers of a parent with dementia. Through this analysis of semi-structured interviews with 12 adult daughter caregivers, we substantiate the importance of studying compassion fatigue in daughter care-givers as a possible precursor to adverse caregiving outcomes and encourage further exploration of this relatively neglected aspect of family care in the home.

BACKGROUND

References to compassion fatigue have appeared in the literature since 1992, when the concept was introduced to the healthcare community, as feelings of anger, inefficacy, apathy, and depression, resulting from a caregiver’s inability to cope with devastating stress (Joinson, 1992). Compassion fatigue was first explored in nurses and, as other caring professions, such as social work and psychology, later adopted the concept, its definition was adapted to focus on prolonged exposure to suffering as one of its primary causes (Figley, 1995; Figley, 2002; McHolm, 2006; Sabo, 2006). In the professional caregiver literature, compassion fatigue has an acute onset and engenders negative emotional responses to caregiving (Figley, 2002; Sabo, 2006). These responses include helplessness, hopelessness, an inability to be empathic, and a sense of isolation (Adams et al., 2008; Joinson, 1992; McHolm, 2006; Robins, Meltzer, & Zelikovsky, 2009).

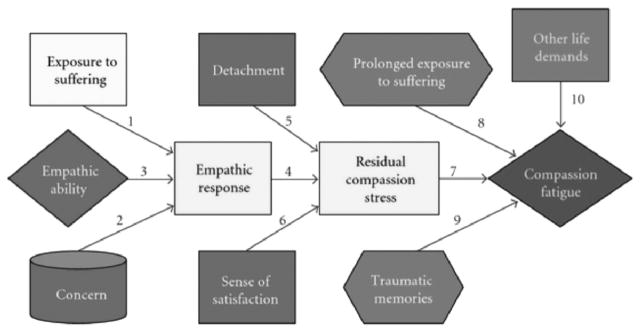

As shown in Figure 1, compassion fatigue is a process beginning when a caregiver experiences concern for a person suffering. This creates an empathic response in the caregiver and, when coupled with an inability to detach from the caregiving situation and dissatisfaction, a resulting compassion stress. Compassion fatigue then develops from compassion stress when the caregiver is continually exposed to suffering, competing life demands, and traumatic memories (Figley & Roop, 2006). Compassion fatigue is distinct from depression or burden because it involves observations of someone who is suffering, and results in feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and social isolation, leading to the growing inability to be empathic.

FIGURE 1.

The Compassion Fatigue Process originally designed by Figley in 2001, and later presented in Figley & Roop (2006).

Caregivers experiencing compassion fatigue may relinquish care of their family member to long-term care. Caring for an older adult at home is costly and the annual out-of-pocket costs to a caregiver averages US$5,431, yet these costs are significantly less than caring for older adults in long-term care settings (AARP Public Policy Institute, 2008; Van Houtven & Norton, 2004). Recurrent themes in the literature suggest the concept of compassion fatigue may be applicable to family caregivers as well as professional healthcare providers, though little research has explored compassion fatigue in family caregivers (Day & Anderson, 2011; Perry et al., 2010; Ward-Griffin, St-Amant, & Brown, 2011).

Perry, Dalton, and Edwards (2010) explored compassion fatigue in family caregivers who assisted in caring for their family member with dementia residing in long-term care settings and validated the presence of compassion fatigue in these family members, as well as factors leading to compassion fatigue. Caregivers described the caregiving role consuming their lives and also spoke of an overwhelming sadness. Perry and colleagues (2010) suggested future research on the topic

In a similar qualitative study, Ward-Griffin, St-Amant, and Brown (2011) explored compassion fatigue in nurse-daughters assisting in the care of an aging parent residing in long-term care. Daughters described love and concern for their parents and intense, prolonged caregiving contributed to compassion fatigue (Ward-Griffin et al., 2011). Nurse-daughter caregivers also reported feelings of intense guilt and sleep disturbances related to compassion fatigue (Ward-Griffin et al., 2011). These two studies suggest the presence of compassion fatigue in family caregivers for relatives residing in long-term care, but there is little in the literature about compassion fatigue in adult children caring for an aging relative in the home.

Day and Anderson (2011) have speculated attachment, empathic ability, and the child caregiver’s concern for the parent might provide a foundation for development of compassion fatigue and of all family caregivers, adult daughters might be at greatest risk for compassion fatigue. The adult daughter care-giver who perceives the aged parent to be suffering, concurrently must deal with competing life demands and a declining sense of life satisfaction, yet be unable to detach from the parent care situation.

Adult child and spousal caregivers experience caregiving differently. In a study of 251 caregivers, spousal caregivers were found to have a more positive perception of the care recipient with dementia’s quality of life than the adult child caregivers (Conde-Sala, Garre-Olmo, Turro-Garriga, Vilalta-Franch, & Lopez-Pousa, 2010). Child caregivers were more likely to be employed and had additional family, such as children or dependents (Conde-Sala et al., 2010). Findings from additonal studies validate the demands on adult children from employment, and include role strain and depressive symptoms for adult child caregivers resulting from work demands (Wang, Shyu, Chen, & Yang, 2011). A meta-analysis of 168 studies comparing spouses, adult children, and children-in-law care-givers for older adults, noted significant differences between spouse and adult child caregivers (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2011). Adult children caring for a parent were more likely to be employed, female, and to be caring for older care recipients, but were less likely to reside with the care recipient than spousal caregivers (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2011). Adult children might be at greater risk for compassion fatigue because they observe the suffering of the aged parent, coupled with a parent’s steadily declining quality of life. Further, daughter caregivers report more days with decreased mental health when compared with wives (Simpson & Carter, 2013). Thus, the intent of this analysis was to identify and explore risk factors of compassion fatigue in adult daughter caregivers of a parent with dementia and to determine whether further research on compassion fatigue in family caregivers is warranted.

METHODS

Project ASSIST: the Parent Study

The parent study supporting this project: Project ASSIST (Assistance, Support, and Self-Health Initiated through Skill Training) is a recently-completed randomized trial of family caregiver homecare skill training. The aim of the parent study was to determine the results of an intervention designed to decrease depressive symptoms and caregiver burden, and increase Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson disease (PD) caregiver preparedness. Data from Project ASSIST has been presented elsewhere (Davis, Gilliss, Deshefy-Longhi, Chestnutt, & Molloy, 2011; Davis, Weaver, & Habermann, 2006; McLennon, Habermann, & Davis, 2010; Shim, Landerman, & Davis, 2011; Shim, Barroso, & Davis, 2012).

In the ASSIST study, a score of ≤23 on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to determine care recipient eligibility (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to conducting the current study, and all interviews used for this analysis were de-identified.

Semi-structured Interviews

In the parent study, semi-structured interviews with care-givers were conducted by study staff (psychology students, social workers, and nurses) who had received 24 hours of training in using an interview guide. A member of the research team or the study project manager reviewed samples of audiotaped interviews on a monthly basis to assure staff consistency in the interviewing process, and interviewers were re-trained as needed. All interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes and occurred prior to completion of the quantitative measures. Interviewers asked the caregivers to describe difficult or stressful aspects of caregiving that occurred in the past month. Caregivers were then asked to describe aspects of caregiving they found to be positive or events that went well in the past month. Interviews were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Only baseline interviews were used for the current study to avoid potential bias associated with the participants’ subsequent involvement in ASSIST.

Participant Sub-sample

Project ASSIST had 187 care dyads, of which 102 were AD caregivers. Of these AD caregivers, 29 were adult daughters (28%). Baseline interviews of 12 adult daughter caregivers for older adults with AD were chosen from Project ASSIST for this study. Using stratified purposive sampling, the first six daughters were selected to represent caregivers with a range of caregiving experience. The 29 adult daughters caring for a parent with AD were rank ordered on their caregiving experience (number of years caring). Two caregivers with little (0–2 years), two with moderate (3–5 years), and two with considerable caregiving experience (6+ years) were arbitrarily selected based only on their years of caring. Following analysis of the first six interviews, additional daughters were selected in the same manner until data saturation occurred with a total of 12 daughters. This wide range of experience was chosen to assure diversity in participant responses.

To be included in Project ASSIST, caregivers had to be providing care for at least 6 months. For this analysis, caregivers also had to be daughters caring for a parent with AD. Demographic data for the sub-sample is presented in Table 1. The 12 daughters were all women, aged 47–65, and had a mean length of time caregiving of 3.3 years, with 7 years as the longest duration of caregiving. In total, 11 daughters in the study were caring for a mother and one daughter was providing care for her father.

TABLE 1.

Caregiver demographic data

| Daughter caregiver | Age | Race | Parent relationship to caregiver | Years of education | Years caregiving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59 | White | Mother | 16 | 6 |

| 2 | 54 | Black | Mother | 13 | 7 |

| 3 | 59 | White | Mother | 16 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 56 | Black | Mother | 14 | 3 |

| 5 | 60 | White | Mother | 16 | 4 |

| 6 | 54 | White | Mother | 14 | 1 |

| 7 | 49 | Black | Mother | 14 | 5 |

| 8 | 52 | Black | Mother | 14 | 1 |

| 9 | 49 | Black | Mother | 16 | 3 |

| 10 | 63 | White | Mother | 16 | 3 |

| 11 | 65 | White | Mother | 9 | 2 |

| 12 | 47 | White | Father | 16 | 4 |

Data Analysis

In Project ASSIST, caregivers were asked open-ended questions about their challenges and satisfactions with caregiving; audiotaped interviews were transcribed verbatim and verified for accuracy with the caregiver. For this analysis, verbatim transcripts of the caregiver interviews were analyzed using qualitative content analysis (Sandelowski, 1995). The analysis focused on the concepts related to the compassion fatigue process. Each interview was read through as a whole for the preliminary analysis. During this first read, the main points were underlined and a brief abstract of the interview was written (Sandelowski, 1995). Next, the transcripts were coded for manifest content, labeling what the text said (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Sandelowski, 1995, 2000). A priori codes based on the model of the compassion fatigue process were first used for any data representing contributing factors, indicators, and outcomes of compassion fatigue; these included: exposure to perceived suffering; motivation to respond; inability to detach; empathic response; lack of satisfaction; competing life demands; helplessness; hopelessness; apathy; and emotional disengagement. New codes, such as coping strategies and obligation, were added until all data were coded. All interviews were first coded individually. To enable the visual analysis of the data for themes, each participant’s quotes for each code were placed in a matrix, or table, with rows for each code and columns for related quotes, plus a column for comments from the research team. Other column headings were indications of coping and emotional responses and many of the a priori codes related to the compassion fatigue process were incorporated under these columns, particularly the emotional responses column. The 12 individual matrices were then combined and the resulting matrix was analyzed to identify themes.

To address credibility, a coding manual was created and agreed upon between the investigator and the principal investigator (PI) of the ASSIST study (Weber, 1990). The coding manual included definitions and examples for each code. Other strategies to maintain rigor were used in the parent study and this analysis. The coding manual and the matrix, particularly the column with comments from the research team, addressed the dependability of the study and provided the analytic documentation for the study (Robinson Wolf, 2003). The detailed reporting of findings from this analysis will increase the transferability and other qualitative studies have reported results with a similar sample size (Perry et al., 2010; Tan & Schneider, 2009).

FINDINGS

Four themes emerged from the analysis supporting the possibility that daughter caregivers might be at risk for developing compassion fatigue. The four themes were: (a) uncertainty; (b) doubt; (c) attachment; and (d) strain. These four themes are notably connected to the contributing factors for compassion fatigue, particularly empathic ability and empathic concern, inability to detach, and other life demands. These findings are significant because they suggest, for the first time, that the family members caring for an older adult at home might be at risk for developing compassion fatigue, and provide justification for further research on compassion fatigue in this population.

Uncertainty

The uncertainty theme is related to the adult daughter caregivers feeling unsure when caring for their parents. Often, their uncertainty was related to AD and the trajectory of illness. Adult daughter caregivers often stated they were uncertain how to respond in a situation and were fearful that something distressing would happen to their parents if they did not act appropriately. As one caregiver stated when asked about a caregiving challenge:

Knowing when her sugar’s going to drop. Being prepared to help her when [it] does. Then, when something happens to her that I don’t really know what’s happening.

Another daughter caregiver explained:

The fear of the unknown, what’s going to happen next, and will I pick up on it quick enough so she’s not in danger or has she ever run away. No, but I’m worried about it. And then health wise, too, it’s just like when you have little kids and you’re the mom trying to keep everybody alive. Well, I’m still doing that.

Similarly, a daughter who had experienced her mother wandering from home on one occasion continued to worry about when it might happen again. She explains:

The day that she walked away from the house, from that day up until then, I was not daily worried about it. But when that happened, it’s just been a constant in the back of my mind. What could happen the next time?

Another caregiver described the confusion she feels when trying to understand how dementia has affected her mother:

So sometimes I do think that she knows what she’s doing or where she is or what’s going on with her. And then by the same token, something else will happen and then I’ll realize that oh no! So it’s a little bit confusing. You don’t really know where the truth begins and something else ends or whatever.

Caregivers described how dementia seemed to change their parents’ personalities and created uncomfortable situations. One daughter explained that her mother had become fearful of persons of a different race. The mother’s fear had an effect on situations ranging from the nurses the daughter could hire, to the shows they could watch on television together. The daughter described being ‘on pins and needles’ and ‘would be humiliated if Mother said something’, and this caused her ‘constant worry.’

Doubt

Other times, caregiving daughters expressed doubt about their ability to meet their parents’ needs, feeling a discrepancy between their expectations for themselves as caregivers and the way in which they were actually caring for their parents. Daughters reported feeling that they were not caring for their parents the way their parents deserved. In addition, caregiving daughters tried to prevent their parents from feeling upset regarding issues related to dementia, such as when a parent did not remember the daughter’s name. As one daughter stated:

I just felt like I didn’t handle that very well, so that was a real bad thing. That kind of bothered me. And when she first came home from the hospital, not knowing that the head wasn’t allowing the body to get up. [Mother] sat in that bathroom all night long.

Another daughter described how she wanted to care for her mother and felt she was not doing the job well. She described a situation in which she cooked for her mother and developed negative feelings about herself because she did not feel that she could make her mother happy:

Not feeling that I’m able to take care of her the way I should be able to take care of her. I took care of [people] in a nursing home. I should be able to do more for her, and I can’t. I can’t make her happy, walk with her, do what she likes to do. And she’s told me I don’t have to. But it’s hard. She’s my mama. And I have to get over that. I couldn’t cook dinner right. [I felt] like I was useless and stupid and dumb. I tried not to let her see it. I try to remember that she has Alzheimer’s, and it’s not her fault.

The previous statement illustrates the concept that the daughters were trying to prevent their parents from experiencing distress from symptoms of dementia. The adult daughter caregivers perceived their parents’ suffering and did not want to increase it. One daughter stated:

I’m more concerned I might say or do something that might upset her. And I don’t want to do that. I would do anything to keep her from getting upset or angry. There’s a saying that you want to hurt me, that’s one thing. But you go after my mother, as my dad would say, ‘God had better take your soul because your rear end is mine.’ I will go for the jugular if anyone even thinks about hurting her. She means that much to me.

In addition, caregivers tried to advocate for their parents. As one daughter describes:

It made me think maybe I should be more of an advocate for Mother and maybe I should be firmer in what I want them to let her do. And I feel that maybe she just sat there and has just been sitting there on the sofa all day long, and has not had anything to stimulate her. So I told ‘em when I take her there now, I make them put her in the little wheelchair, and I say, ‘I want mother to participate in all the activities.

These daughters desired to protect their parents from any suffering and a caregiver’s exposure to perceived suffering is a contributing factor for compassion fatigue.

Attachment

As anticipated, daughters caring for parents with dementia were emotionally attached to their parents and expressed willingness to care for them. These caregivers also described satisfaction from caregiving. This theme was most evident in the caregiver responses to the interviewer asking the question, ‘What are some of the positive experiences that you’ve had as a caregiver for your parent?’ Caregivers often responded with specific stories. One caregiver told of lying in bed with her mother and enjoying the time with her:

Oh yeah, this morning. We . . . crawled in bed together. Just because it made me feel like I was loved. And I was with my mama. And I miss not having her around like she used to be.

Another daughter stated:

Oh, yeah, we have some times we laugh. Sometimes she come back in and be on a, wow, I mean, all the way up. She just be like she’s totally back. And we just sit and laugh and cackle.

These stories illustrate the relationship between caregiver and care recipient and although the relationship changes, the daughters are still connected with their parents. A prior positive relationship and emotional attachment motivated the daughters to care for their parents. As one daughter said,

So then I know what I need to do to care for her. And I feel good about doing that because I know she’s taken care of me all my life.

Another caregiver articulated this:

Our values are the same. I mean, she raised me, and she’s an excellent mom and my dad was an excellent dad, so I like her so I can say I think it would be harder if you were a caregiver and maybe you didn’t have a good relationship with that parent and maybe you really didn’t like them and you were doing it because it was the right thing to do and all that, but in her case, I think she deserves it, the best I can do.

Even though the parent–daughter relationship changed, caregiving daughters also felt that their relationship with their parents was bettered through caregiving:

I just got to know them in a different way that I never got to know and I really got to experience, and still do, unconditional love.

When describing how she found satisfaction in caring, this same daughter continued:

It just makes it all worthwhile when they become so tender and so gentle and they’re not your parents anymore in a way.

Daughters also told of their parents’ personal histories and past experiences and how this was important in the way they approached caregiving. Many daughters felt their parents had not had a good life and through caring for their parents, the daughter caregivers were able to make up for this:

And knowing that my mother has been the sweetest person in the world. She never said anything bad about anybody. We called her a Pollyanna because she always saw the good side of everything. No matter what it was. If I was going to the doctor and didn’t want to [she would say] ‘Well just be glad you have a doctor to go to.’

Another daughter added: ‘But I just feel like she has never ever had a great life.’ Daughters were motivated to care for their parents and in turn received satisfaction from this. One daughter, however, did not find joy in caregiving, nor did she feel satisfaction from caring for her mother. This daughter, possibly experiencing compassion fatigue, expressed her hopelessness, anger, and frustration saying:

It upsets me, the disease – the horrible disease. I don’t know. When I’m bathing her, I don’t have time to think about anything else, to tell you the truth. But when I do think about it, I hate it. I hate that disease. And I don’t hate things or people, but I hate that disease. I hate it. And I would do anything if I could help find a cure for it.

The relationship between parents and adult daughter caregivers likely places the caregivers at risk for compassion fatigue; while at the same time, this close emotional relationship provides the motivation for caregivers to care for their parents. In addition, daughters found satisfaction in caregiving through their attachment to their parents.

Strain

All of the daughter caregivers described competing life demands, another contributing factor for compassion fatigue. Caregivers’ competing demands ranged from husbands and jobs, to church activities and grandchildren. Daughter caregivers had to take time from other activities to care for their parents and often felt that they were missing out on things. Daughters caring for parents with dementia spoke of how physically tired they were. One daughter fell asleep on her way home from work and was in a car accident:

That kind of has my rest broken, and when I get to work the next day, I’m just no good, I’ll be sleep all day. And I just can’t hardly function and for a while when I would be coming home from work, I would actually be sleep, and I would just nod off.

Another daughter described the stress she felt when trying to help her daughter plan a wedding, while caring for her mother:

My daughter got married and I had to help her plan and do showers, and the wedding, and all of these things around my mom. And every time something important happened, my mother would wind up at the doctor or a hospital. It was really, really hard.

This same daughter discussed how difficult it is for her to do all of the things in her life that she would like to when she says,

Juggling my time, taking care of the house here, and my house there, and my job and friends and family. It’s just hard to juggle it sometimes.

In response to caregiver strain, daughters also described feeling resentful towards their parents when the tasks became overwhelming. One daughter describes it:

I think I had reached a point where I felt resentful toward her. I used to love the weekends. I dread Fridays because that means that I don’t have any relief at all. All Friday night . . . Saturday . . . Sunday.

As one daughter simply said, ‘You can’t stop.’

In response to competing life demands, daughter caregivers described reaching out to family members for help and relief. Often, the help was another sibling, and some caregivers shared that they had looked into either adult day-care or long-term care facilities for their parents. Some caregivers had scheduled breaks from caregiving or activities to help ease some of the caregiving burden; one daughter had weekly ‘dates’ with her husband, another had a standing weekly phone call with her cousin, and a third daughter arranged a schedule with her sister for alternating weeks bathing their mother. These coping strategies allowed the daughters to continue caring for their parents and buffered against developing compassion fatigue.

DISCUSSION

While this study did not confirm the presence of compassion fatigue as professional caregivers have experienced it, the interviews and statements from these daughters suggest that family caregivers might be at risk for compassion fatigue. This analysis provides evidence for many of the concepts from the model of the compassion fatigue process (Figure 1) leading to a caregiver developing compassion fatigue. Daughter caregivers articulated the contributing factors for compassion fatigue as an inability to detach, or attachment, other life demands, and an exposure to suffering expressed by the themes of uncertainty and doubt.

Adult daughters in this study described feelings of uncertainty and doubt in response to caring for a parent with AD. While uncertainty and doubt were not contributing factors represented in Figley and Roop’s (2006) model of the compassion fatigue process, these themes demonstrate the complexity in providing care for a parent with AD and are reflective of a perceived suffering. Daughters perceived suffering of a parent and tried to minimize this suffering, but were often unsure how best to react and doubted their responses to distressing situations for their parents. The feelings of uncertainty and doubt found in this study are the outcomes of the daughters’ exposure to suffering and the fear they felt that something upsetting would happen to their parent if their response was not appropriate. The daughters in this sample tried to prevent their parents from experiencing the negative outcomes related to AD, such as when a parent could not remember a daughter’s name. This exposure to suffering and the caregivers’ desire to decrease the suffering are the first steps in the process of compassion fatigue.

The themes of uncertainty and doubt found in this study are similar to the feelings of inadequacy and powerlessness experienced by nurse-daughters while assisting with care for a parent in long-term care (Ward-Griffin et al., 2011). Based upon these and their other findings, Ward-Griffin and colleagues (2011) concluded nurse-daughters were at risk for compassion fatigue. In another study, Lu and Haase (2009) concluded that family caregivers’ spouses with mild cognitive impairment, experienced ‘shock, anger, guilt, frustration, sadness, loneliness, helplessness, and uncertainty’ (p. 9). Participants in their study, however, had not been diagnosed with AD, as were the care recipients in Project ASSIST.

All daughters experienced strain and described competing life demands. Other studies have generated similar findings particularly when participants were adult children caring for a parent with dementia (Conde-Sala et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Strain and other demands often are associated with care-giver employment (Conde-Sala et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). One participant in this study described such exhaustion that she fell asleep behind the wheel while returning home from work. When considered in combination with the exposure to perceived suffering and a desire to minimize or alleviate the suffering, these other demands place the caregivers at risk for compassion fatigue.

In addition, all 12 daughters articulated strong, ongoing attachment to their parent. Attachment and affection for the parent may demonstrate the daughters’ inability to detach from the caregiving situation, which in professional caregivers was another factor contributing to development of compassion fatigue. However, the attachment between a daughter caregiver and parent might be a protective factor against compassion fatigue. Many daughters in this study linked their satisfaction with providing care to their relationship with their parent. The daughters interviewed often spoke of attachment in a positive sentiment and it was their motivation to continue caring. A longitudinal study with 116 married or co-habiting dementia caring dyads, found caregivers with secure attachment had significantly higher levels of wellbeing than caregivers with insecure attachment (Perren, Schmid, Herrmann, & Wettstein, 2007). Roughly 75% of couples in the study were securely attached and although this study did not include adult children, the results illustrate the important effect attachment might have on the caregiver’s emotional wellbeing (Perren et al., 2007). Additional, in-depth understanding of the relationship between attachment and the inability to detach would provide more information about the application of compassion fatigue to family caregivers.

The findings from this study are similar to other studies of dementia caregivers and describe the difficulty in caring for a family member with dementia (Bandeira et al., 2007; Ott et al., 2007; Papastavrou, Kalokerinou, Papacostas, Tsangari, & Sourtzi, 2007). Healthcare providers need to be aware that family caregivers might be at risk for compassion fatigue, and more research on compassion fatigue in family caregivers is needed to fully understand compassion fatigue as experienced by family caregivers. Future research might enable healthcare professionals to identify family caregivers who are at particular risk for compassion fatigue. With this knowledge, researchers might develop screening tools to help identify this vulnerable group of caregivers and track the outcomes of interventions designed to help family members cope more effectively with compassion fatigue.

Once compassion fatigue is recognized and effectively examined in family caregivers, healthcare providers will be positioned to develop and test interventions. Adult children caregivers represent a rapidly growing segment of the caregiving population and need interventions and assistance because they are suffering negative consequences of caregiving. If nurses are able to understand and recognize compassion fatigue, we can alleviate selected contributing factors, such as an exposure to suffering, thereby protecting the caregiver from the development of compassion fatigue. Nurses can support family caregivers through interventions directed at decreasing uncertainty and providing caregivers with increased feelings of control and ability. In addition, interventions designed to capitalize on the attachment between a caregiving daughter and her parent might allow care-givers the opportunity to draw resilience from their parent–child relationship. Further interventions might include anticipatory guidance and support for caregivers at risk for compassion fatigue. Other interventions might incorporate online resources that would fit into caregivers’ complicated schedules.

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. This study included 11 daughters caring for a mother and only one daughter caring for a father. While different themes were not evident in our analysis between these daughters, a larger sample might reflect additional challenges related to caring for a father compared with a mother. Future studies should attempt to address this limitation and explore the effects of parent gender on daughter caregiver responses in further detail.

Most daughters in this study reported having some type of support, whereas in prior studies, only 68% of family caregivers for adult care recipients with various illnesses reported having help from at least one unpaid caregiver and 65% of dementia caregivers used at least one community service (Brodaty, Thomson, Thompson, & Fine, 2005; National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2009). Many daughters in this study who provided care in their home used outside services, such as adult daycare or had aides come into the home to assist with care. Those that did not, relied on family members for respite care. The disproportionate presence of outside support might be due to the nature of the ASSIST parent study. By virtue of this, participants were already likely seeking help of some kind. It is possible, given the importance of support as a moderator for compassion fatigue, that women with little or no support may display indications of compassion fatigue to a greater degree than the daughters in this study.

Lastly, the aims and research questions for this study differed from those of the parent study. Caregivers in the parent study were asked to describe three difficult or stressful aspects of caregiving that occurred in the past month and to describe three aspects of caregiving they found to be positive, or events that went well in the past month. Those questions focused caregivers’ answers on difficult or positive aspects of caregiving, but other known contributing factors to compassion fatigue, such as traumatic memories, might have been omitted from the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study is the first to explore the concept of compassion fatigue among daughters caring for a parent with dementia at home. Study findings demonstrated these daughters experienced contributing factors of compassion fatigue, and thus appeared to be at risk for developing compassion fatigue. These findings support the importance of a larger study exploring compassion fatigue and its contributing factors and consequences in this population. Future studies should examine compassion fatigue and the negative outcomes associated with it in at risk caregiver populations. If compassion fatigue in family caregivers is well understood, healthcare providers may be able to assess family caregivers for its presence, and intervene. Healthcare providers, particularly nurses, are in a role to identify family caregivers at risk for compassion fatigue and provide emotional and practical support to these caregivers to reduce or ameliorate compassion fatigue.

Acknowledgments

Project ASSIST for Chronic Illness Caregivers was funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research Grant R01 NR008285. Funding for this study was supported in part by CTSA Grant TL1RR024126 from National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- AARP Public Policy Institute. Valuing the invaluable: The economic value of family caregiving, 2008 update. Washington, DC: AARP; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Figley CR, Boscarino JA. The Compassion Fatigue Scale: Its use with social workers following urban disaster. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;18(3):238–250. doi: 10.1177/1049731507310190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10(2):e47–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira DR, Pawlowski J, Goncalves TR, Hilgert JB, Bozzetti MC, Hugo FN. Psychological distress in Brazilian caregivers of relatives with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11(1):14–19. doi: 10.1080/13607860600640814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Thomson C, Thompson C, Fine M. Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don’t use services. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):537–546. doi: 10.1002/gps.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, Lopez-Pousa S. Quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Differential perceptions between spouse and adult child caregivers. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2010;29(2):97–108. doi: 10.1159/000272423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G. Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):929–936. doi: 10.1002/gps.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Gilliss CL, Deshefy-Longhi T, Chestnutt DH, Molloy M. The nature and scope of stressful spousal caregiving relationships. Journal of Family Nursing. 2011;17(2):224–240. doi: 10.1177/1074840711405666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Weaver M, Habermann B. Differential attrition in a caregiver skill training trial. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29(5):498–506. doi: 10.1002/nur.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J, Anderson RA. Compassion fatigue: An application of the concept to informal caregivers of family members with dementia. Nursing Research and Practice. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/408024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress in those who treat the traumatized. Levittown, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58(11):1433–1441. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR, Roop RG. Compassion fatigue in the animal-care community. Washington, DC: Humane Society Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joinson C. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing. 1992;22(4):116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidel GC. Burnout and compassion fatigue among hospice caregivers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2002;19(3):200–205. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YF, Haase JE. Experience and perspectives of caregivers of spouse with mild cognitive impairment. Current Alzheimer Research. 2009;6(4):384–391. doi: 10.2174/156720509788929309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHolm F. Rx for compassion fatigue. Journal of Christian Nursing. 2006;23(4):12–19. doi: 10.1097/00005217-200611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennon SM, Habermann B, Davis LL. Deciding to institutionalize: Why do family members cease caregiving at home? Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2010;42(2):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. 2009 National Alliance for Caregiving/AARP survey. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Sanders S, Kelber ST. Grief and personal growth experience of spouses and adult-child caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):798–809. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastavrou E, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas SS, Tsangari H, Sourtzi P. Caring for a relative with dementia: Family caregiver burden. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(5):446–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Schmid R, Herrmann S, Wettstein A. The impact of attachment on dementia-related problem behavior and spousal caregivers’ well-being. Attachment & Human Development. 2007;9(2):163–178. doi: 10.1080/14616730701349630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Dalton JE, Edwards M. Family caregivers’ compassion fatigue in long-term facilities. Nursing Older People. 2010;22(4):26–31. doi: 10.7748/nop2010.05.22.4.26.c7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: A meta-analytic comparison. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0021863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins PM, Meltzer L, Zelikovsky N. The experience of secondary traumatic stress upon care providers working within a children’s hospital. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009;24(4):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson Wolf Z. Exploring the audit trail for qualitative investigations. Nurse Educator. 2003;28(4):175–178. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo BM. Compassion fatigue and nursing work: Can we accurately capture the consequences of caring work? International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2006;12(3):136–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo BM. Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2011;16(1):1. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01Man01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(4):371–375. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, McGinnis KA, Zhang S, Martire LM, Hebert RS, Beach SR, et al. Dementia patient suffering and caregiver depression. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2008;22(2):170–176. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher KL, Beck CA, Marren JM. Family caregivers: Caring for older adults, working with their families. American Journal of Nursing. 2006;106(8):40–49. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim B, Landerman LR, Davis LL. Correlates of care relationship mutuality among carers of people with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(8):1729–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim B, Barroso J, Davis LL. A comparative qualitative analysis of stories of spousal caregivers of people with dementia: Negative, ambivalent, and positive experiences. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2012;49(2):220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C, Carter P. Mastery: A comparison of wife and daughter caregivers of a person with dementia. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2013;31(2):113–120. doi: 10.1177/0898010112473803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan T, Schneider MA. Humor as a coping strategy for adult-child caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatric Nursing. 2009;30(6):397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DH, Jr, Ezell M, Kuchibhatla M, Ostbye T, Clipp EC. Identifying trajectories of depressive symptoms for women caring for their husbands with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(2):322–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Norton EC. Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23(6):1159–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YN, Shyu YI, Chen MC, Yang PS. Reconciling work and family caregiving among adult-child family caregivers of older people with dementia: Effects on role strain and depressive symptoms. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(4):829–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C, St-Amant O, Brown J. Compassion fatigue within double duty caregiving: Nurse-daughters caring for elderly parents. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2011;16(1):4. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01Man04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber RP. Basic content analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]