We are all agreed: patient-centred care (PCC) is a ‘good’ thing and we all want to see more of it. PCC has become an ‘article of faith’ for all of us wishing to create a 21st century health service. Simon Stephens, the NHS Chief Executive, in his Five Year Forward View, calls for the ‘renewable energy’ that patient’s carers and communities can offer the NHS.1

Safe and effective care can only be achieved when patients are ‘present, powerful and involved at all levels.2 Never has so much health policy been developed by so many with so little impact on the day-to-day clinical business of the NHS!

Patient surveys over the past decade have been consistent in reporting that we (the clinicians, the managers, and the patients are not delivering PCC, nor are we implementing PCC ‘at scale’ in any meaningful way. Indeed, in the most recent surveys, for example, only 3.2% of patients with long-term conditions (LTCs) report involvement in developing their own care plan.3 The gap between the rhetoric and the reality remains uncomfortably wide.

PATIENT-CENTRED CARE

All things to all people?

PCC can mean different things to different people at different times. The health Foundation describes the four principles of PCC as care that is coordinated, personalised and enabling, and where a person is treated with ‘dignity, compassion, and respect’,4 and the Royal College of General Practitioners5 defines PCC as ‘...care that is holistic, empowering and tailors support according to the individual’s priorities and needs’. These definitions applied to both systems and individuals are not fundamentally different, but they are capable of many different interpretations.

Fundamentally, PCC is about ‘changing the conversation’ by a ‘transfer of power’ between clinicians and people attending for consultations. This is the major challenge to the implementation of PCC ‘at scale’ as the ‘norm’ of NHS clinical practice. Our training and our experience have not prepared us for the cultural change required; patient empowerment challenges our internal schemata about how things should be done in clinical practice. Interventions such as support for self-management, shared decision making, and patient activation, which may not come naturally to us, should all be part of PCC in clinical practice.

The acquisition of new knowledge and skills to use these interventions can only take us so far, changing the attitudes developed during our training is far more difficult. One of the difficulties with PCC pilots has been to ensure that the purpose and the essential principles of PCC have not been lost in implementation, or in the ‘scaling up’ of the schemes and in ensuring consistency of delivery. One manifestation of PCC is collaborative care and support planning (CCSP), and the introduction of a direct enhanced service has certainly raised the profile of CCSP within everyday clinical practice. Its purpose, however, has been instrumental, focusing on outcomes (reducing the number of unplanned hospital admissions), rather than the process of changing the conversations between clinicians and patients: CCSP has become another managerial exercise for GPs.

The evidence

However, there is an overwhelming amount of evidence supporting the effectiveness of PCC. National Voices recently compiled information from a large number of systematic reviews (n = 779) to identify the ‘core facets’ of PCC.6 These core facets were: supporting self-management and shared decision making, enhancing experience, improving information, and understanding and promoting prevention. A recent Cochrane Review7 concluded that involvement in PCC probably leads to only small improvements in some indicators of physical health (for example, HbA1c and control of asthma), but they do improve patients’ confidence and skills to manage their own health. It is clear that changing the conversation cannot occur in isolation: whole-system change is also required.

There is no shortage of instruments and tools to help us measure PCC in our practices. De Silva, using a definition of a person-centred health system as ‘...one that supports people to make informed decisions about, and to successfully manage, their own health care, able to make informed decisions and choose when to allow others to act on their behalf’, summarised themes from more than 23 000 studies measuring PCC or its components and included specific examples from 921 studies in her review.8 She concluded that it is a priority to understand what ‘person centred’ means because, until we know what we want to achieve it is, of course, difficult to know the most appropriate way to measure it.

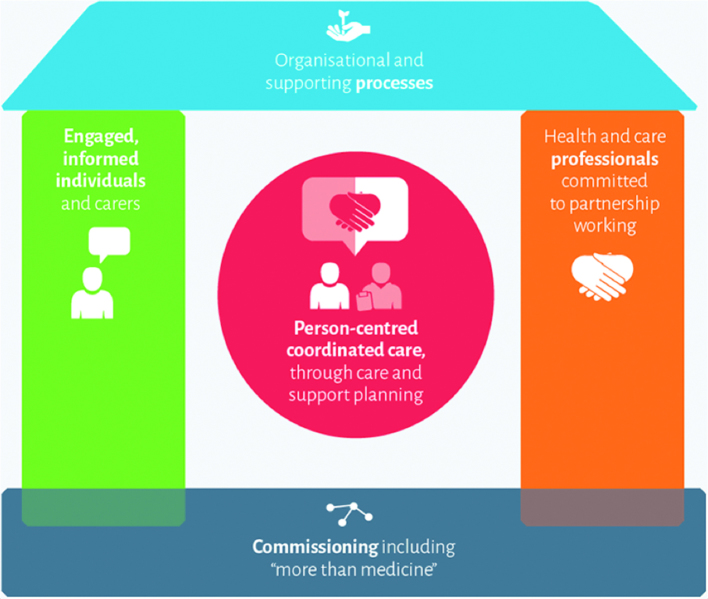

A large number of tools are available to measure PCC but in the absence of an agreed definition, we do not know which are most useful. Combining a range of methods and tools is likely to provide the most robust measure of PCC. The House of Care (HoC) framework,9 used to successfully improving the care of people with diabetes in Tower Hamlets, provides one of the best frameworks using system change to implement PCC by evaluating both process and outcomes.10

This framework has CCSP at its heart, supporting the process of changing the conversation between clinician and patient. Such new conversations cannot take place in isolation. The HoC identifies the four other essential components of the system which need to be addressed for CCSP to take place. These are:

engaged, informed individuals and carers (left wall)

health and care professionals committed to partnership working (right wall)

commissioning including ‘more than medicine’ (floor)

organisational and supporting processes (roof)

The BJGP will be considering each of these key elements in turn in a series of articles, the first of which can be found in this issue, which address the challenges and supportive factors for implementing this transformational change in the delivery of PCC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The House of Care framework.

Making change happen

Key to ‘changing the conversation’ is the development of the essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes for clinicians and their patients to become committed to partnership working.

Fundamental change in attitudes, in the relationships and conversations between people, often requires revolutionary rather than evolutionary change. Many of the changes seen in health-related behaviours (for example, seat belts and smoking) have been the result of evolutionary change through policy development and legislation.

Health social movements (HSMs), are more revolutionary and are generally more focused around health addressing access to, or the provision of, healthcare services.11 It is surely time now to create an HSM to change the conversation and develop our ideas; for example, about how behavioural insights can be used to do this. We already have enough theory, evidence, and a broad consensus and, if the NHS is to become sustainable, all of us need to become far more active participants in our own care. HSMs have been very effective in the past in transforming health services (such as the revolution in our care of people with HIV). Clinical leadership and local champions are essential for building communities of practice: the use of a co-production model to create more equal partnerships between clinicians and people with LTCs is also key to such change in health care.

NESTA (National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts), in its 2030 NHS vision12 envisages new kinds of conversations in consultations ‘structured to encourage and support patients be active participants in their own health’. When the consultation starts, the patient and doctor agree a joint agenda, focus on the goals that are important to that person and the care and support planning process establishes the combination of clinical and social interventions that helps them achieve these.

Kate Granger started a very successful HSM with her request that all clinicians start their consultations with ‘Hello, my name is …’ .13 It takes ‘two to tango’, and if patients and carers are to become fully engaged and informed in care and support planning processes, then it is essential that clinicians, managers, services, and systems invite, enable, and support an active role for patients.4 Just imagine if at our next consultation our patients said to us ‘Hello, my plan is …’

Acknowledgments

Particular thanks to Adrian Sieff of the Health Foundation who provided some of the ideas in this article and reviewed the final document. To learn more about patient-centred care at the RCGP please visit www.rcgp.org.uk/care-planning.

Provenance

Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.NHS England, Public Health England, Health Education England, Monitor, Care Quality Commission, NHS Trust Development Authority Five year forward view. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 26 Nov 2015).

- 2.National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England A promise to learn — a commitment to act: improving the safety of patients in England. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226703/Berwick_Report.pdf (accessed 26 Nov 2015).

- 3.NHS England GP Patient Survey 2013–14. http://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/2014/07/03/gp-patient-survey-2013-14/ (accessed 7 Dec 2015).

- 4.The Health Foundation Ideas into action: person-centred care in practice What to consider when implementing shared decision making and self-management support. http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/IdeasIntoActionPersonCentredCareInPractice.pdf (accessed 7 Dec 2015).

- 5.Royal College of General Practitioners Inquiry into patient-centred care in the 21st century. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/inquiry-into-patient-centred-care-in-the-21st-century.aspx (accessed 26 Nov 2015).

- 6.National Voices Prioritising patient centred care: supporting self management: summarising evidence from systematic reviews. http://www.nationalvoices.org.uk/sites/www.nationalvoices.org.uk/files/supporting_self-management.pdf (accessed 4 Dec 2015).

- 7.Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, et al. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD010523. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Silva D, The Health Foundation Helping measure person-centred care A review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care. http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/HelpingMeasurePersonCentredCare.pdf (accessed 7 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Year Of Care Partnerships. The House. http://www.yearofcare.co.uk/house (accessed 7 Dec 2015).

- 10.The Health Foundation Year of Care: Tower Hamlets Primary Care Trust. http://www.health.org.uk/programmes/year-care/projects/year-care-tower-hamlets-primary-care-trust (accessed 26 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown P, Zavestoski S, McCormick S, et al. Embodied health movements: new approaches to social movements in health. Sociol Health Illn. 2004;21(1):50–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NESTA The NHS in 2030 A vision of a people-powered, knowledge-powered health system. http://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/the-nhs-in-2030.pdf (accessed 26 Nov 2015).

- 13.Granger K. Hello my name is …. http://hellomynameis.org.uk/ (accessed 26 Nov 2015).