Abstract

Background

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a common skin condition in children. Consultation rates and current management in primary care, and how these have changed over time, are poorly described. An association between the presence of atopic eczema (AE) and MC has been shown, but the subsequent risk of developing MC in children with a diagnosis of AE is not known.

Aim

To describe the consultation rate and management of MC in general practice in the UK over time, and test the hypothesis that a history of AE increases the risk of developing MC in childhood.

Design and setting

Two studies are reported: a retrospective longitudinal study of MC cases and an age–sex matched case-cohort study of AE cases, both datasets being held in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink from 2004 to 2013.

Method

Data of all recorded MC and AE primary care consultations for children aged 0 to 14 years were collected and two main analyses were conducted using these data: a retrospective longitudinal analysis and an age–sex matched case-cohort analysis.

Results

The rate of MC consultations in primary care for children aged 0 to 14 years is 9.5 per 1000 (95% CI = 9.4 to 9.6). The greatest rate of consultations for both sexes is in children aged 1–4 years and 5–9 years (13.1 to 13.0 (males) and 13.0 to 13.9 (females) per 1000 respectively). Consultation rates for MC have declined by 50% from 2004 to 2013. Children were found to be more likely to have an MC consultation if they had previously consulted a GP with AE (OR 1.13; 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.16; P<0.005).

Conclusion

Consultations for MC in primary care are common, especially in 1–9-year-olds, but they declined significantly during the decade under study. A primary care diagnosis of AE is associated with an increased risk of a subsequent primary care diagnosis of MC.

Keywords: atopic eczema, children, consultation rates, molluscum contagiosum, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a common skin condition that predominantly affects children,1 and is one of the 50 most prevalent diseases globally.2 MC typically presents as one or more umbilicated, smooth, flesh-coloured, dome-shaped lesions,3 and is usually diagnosed on clinical examination by a GP or dermatologist.4 The condition can impact on quality of life, with around 1 in 10 children experiencing a substantial effect on their quality of life.5

A study in England and Wales described consultation rates during 2006,6 but there have been no recent studies, nor any studies exploring recent changes over time.7 Furthermore, no studies have described primary care management, including prescribing and referrals to secondary care.8

Atopic eczema (AE) has been found to be common in children with MC,9–13 and the prevalence of AE is higher in children with MC than in the general population.14,15 However, most studies describing this association have been based in specialty dermatology clinics,12 and have not explored the temporal relationship between the two conditions. It is not clear whether this relationship holds for children with AE or MC in the community, or whether there is a time-dependent direction, in other words, that children with AE are more likely to develop MC.

This study aimed to describe consultation rates of MC in general practice in the UK, and test the hypothesis that a diagnosis of AE increases the subsequent risk of developing MC in children.

METHOD

Study design and data source

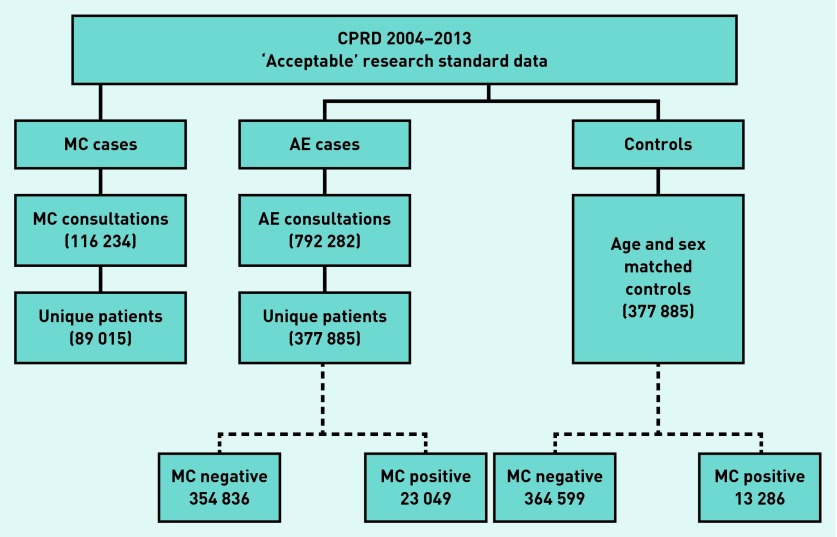

Two analyses using data extracted from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) are reported: a retrospective longitudinal analysis of MC cases presenting to general practice in the UK, and an age–sex matched case-cohort analysis to examine the likelihood of developing MC in children who have previously presented to general practices with AE. MC and AE were defined as having a Read Code for either condition (information available from authors on request) if aged 0–14 years at the time of consultation between 2004 and 2013 (inclusive). Controls for the case-cohort analysis were selected at random within age–sex strata at a ratio of 1:1. Patients were excluded from the population pool before the controls were selected if they had a Read Code of AE, ‘transferred out of practice’, or if they died during the study period. All data were extracted from the CPRD, which is a primary care database of anonymised patient records, representing approximately 6% of the UK population. CPRD contains data on >4 million active patients from >500 primary care practices across the UK.16 The base population for both analyses was all CPRD-registered patients aged 0–14 years per year for the period 2004–2013. Patients must have been registered in the practice during the year to be included within the denominator population for that year. Only data from GP practices that were defined as ‘up to standard’ by the CPRD standard definition were included within the study. The data extraction process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data extraction flow chart. AE = atopic eczema. MC = molluscum contagiosum.

How this fits in

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a common skin condition in children but recent consultation rates have not been described in the UK. It is common that children with MC also present with atopic eczema (AE) to primary and secondary care; however, the risk of developing MC in children with a history of AE is not clear. The largest rate of consultations of MC was found in children aged 1–4 years and 5–9 years (13.1 to 13.0 [males] and 13.0 to 13.9 [females] per 1000 respectively), and consultation rates have decreased from 2004 to 2013 by 50% for MC. Evidence was found of an increased likelihood of subsequent MC in children with a primary care diagnosis of AE.

Statistical analysis

For the retrospective cohort analysis, the consultation rate for MC was calculated using the age-specific number of consultations divided by the total person-years in each age group from the CPRD population. Consultation rates were produced by age and year to produce annual trends. Prescription medications by British National Formulary (BNF) chapter heading, patient episodes, and referrals to dermatology specialty care were described. The age groups used in the analysis were <1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, and 10–14 years.

Matched cohort study

For the matched cohort analysis, logistic regression analysis was used to determine odds ratios (ORs) for the association between ‘exposure’ to AE and the risk of an MC outcome. Baseline exposure to AE was defined as a 30-day AE-free ‘wash-in’ period where there are no consultations for AE prior to an initial MC consultation. Multivariate analyses were also performed to establish associations of developing MC within the group of patients with AE for age, corticosteroid strength, and eczema diagnosis (primary and secondary diagnosis, as identified by Read Codes [information available from the authors on request]).

Significance was assumed at the 5% level, and 95% confidence intervals are reported. Analysis was performed using Stata (version 12).

RESULTS

Retrospective cohort analysis

During the period 2004–2013, there were 116 234 consultations for MC in 89 015 (44 995 males: 50.6%) patients within the CPRD database (Figure 1).

Consultation rate by age and sex

The highest consultation rates were in the 1–4 year and 5–9 year age groups for both males and females. Consultation rates for males were marginally higher in the 1–4 year age group (13.1 per 1000) than in the 5–9 year age group (13.0 per 1000). However, for females the greatest rate of consultations was in the 5–9 year age group (13.9 and 13.0 per 1000 in the 5–9 year and 1–4 year age groups, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Consultation rate for molluscum contagiosum per 1000 registered population, 2004 to 2013, by age group and sex

| Age group, years | Events, n | Population, n | Consultation rate per 1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male (95% CI) | Female (95% CI) | |

| <1 | 547 | 411 | 282 744 | 268 564 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) |

| 1–4 | 17 296 | 16 237 | 1 316 034 | 1 252 919 | 13.1 (12.9 to 13.3) | 13.0 (12.8 to 13.2) |

| 5–9 | 20 151 | 20 600 | 1 552 618 | 1 479 532 | 13.0 (12.8 to 13.2) | 13.9 (13.7 to 14.1) |

| 10–14 | 7001 | 6772 | 1 587 807 | 1 505 629 | 4.4 (4.3 to 4.5) | 4.5 (4.4 to 4.6) |

| Total | 44 995 | 44 020 | 4 739 203 | 4 506 644 | 9.5 (9.4 to 9.6) | 9.8 (9.7 to 9.9) |

Consultation trends

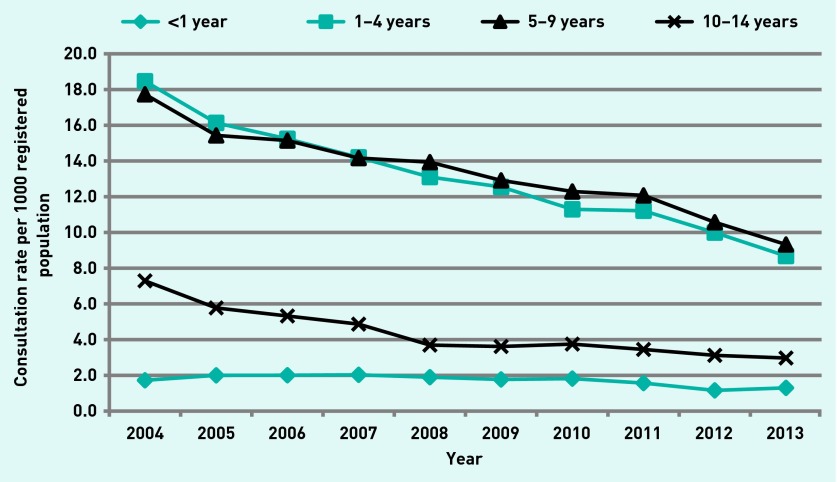

Consultations for MC have been steadily declining from 2004–2013. Rates for males and females have declined by 50% over the 10-year period. Decreases in consultation rates were highest for children within the 1–4 year and 5–9 year age groups (Figure 2). Rates for children aged 10–14 years declined during 2004–2008, and remained constant from 2008–2013. There was little variation in the rate of consultations for children aged <1 year over the 10-year period.

Figure 2.

Consultation rate per 1000 registered population, males and females, by year and age group.

Consultations per patient

Most patients consulting for MC did so once (77.3%, n = 68 820), 17.6% (n = 15 662) had two consultations for MC, and a small proportion (approximately 5%, n = 304) presented on three or more occasions over the 10-year period. The time between MC consultations varied; 89.5% of patients who consulted more than once (n = 20 195) did so within 1 year of their initial consultation. Where data are presented as patient episodes, assuming a singular episode of MC will have multiple consultations within 180 days, 90.4% (n = 80 488) of children had one episode of MC, 9.3% (n = 8300) two, and 0.3% (n = 227) three or more.

Referral to secondary care

There were 733 (0.8% of all consultations) referrals to a secondary care dermatology department for children presenting with MC. The greatest referral rate was in those aged 10–14 years (9.9 per 1000 MC consultations). The rate of referrals from 2004–2013 reduced significantly by 74.4% during the 10-year period. Of the patients who were referred to a secondary care setting, 73.4% (n = 538) had consulted two or more times.

Prescribed medications

A total of 41 489 patients (46.6%) received a treatment during a consultation for MC: 41 419 (99.8%) during a single episode (MC consultation within 90 days of previous) and 70 (2.0%) during a subsequent episode.

Of the 41 489 patients who were prescribed a treatment during a consultation with a Read Code for MC, a total of 71 404 treatments were prescribed. The average number of items per patient was 1.7. Treatments prescribed in over 1% of cases are listed in Table 2 by BNF sub-section headings.

Table 2.

Treatments prescribed during a patient’s consultation for molluscum contagiosum (where prescribed in >1% of cases)

| BNF sub-section heading | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Emollient and barrier preparations | 14 645 | 20.5 |

| Topical corticosteroids | 14 496 | 20.3 |

| Anti-infective skin preparations | 13 075 | 18.3 |

| Antibacterial drugs | 10 647 | 14.9 |

| Antihistamines, hyposensitive and allergic emergencies | 3097 | 4.3 |

| Preparations for warts and calluses | 1727 | 2.4 |

| Bronchodilators | 1635 | 2.3 |

| Skin cleansers, antiseptics, and wound prep | 1412 | 2.0 |

| Analgesics | 1129 | 1.6 |

| Anti-infective eye preparations | 938 | 1.3 |

| Corticosteroids | 829 | 1.2 |

| Topical anaesthetics and antipruritic preparations | 750 | 1.1 |

BNF = British National Formulary.

Matched case-cohort analysis

During the period 2004–2013 there were 792 282 consultations identified with an AE Read Code, representing 377 885 individual patients (Figure 1).

A total of 58.9% of children consulted once for AE, 19.4% did so twice, and one patient consulted 105 times during the 10-year period (Table 3). The mean number of consultations per patient was 2.5.

Table 3.

Consultations for atopic eczema per patient during 2004–2013

| Number of consultations | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 222 710 | 58.9 |

|

| ||

| 3 | 73 270 | 19.4 |

|

| ||

| 4 | 32 523 | 8.6 |

|

| ||

| ≥5 | 49 382 | 13.1 |

|

| ||

| Range | 1 to 105 | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 1 (1 to 3) | |

In children who consulted for both AE and MC, around two-thirds (65.2%) of initial AE consultations were more than 30 days prior to their first consultation for MC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Time between atopic eczema (AE) and molluscum contagiosum (MC) consultations (in cases of AE who also consulted for MC)

| Time from AE to MC consultations | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Initial AE ≥30 days before consultation | 15 016 | 65.2 |

| Initial AE consultation during or after consultation | 7793 | 33.8 |

| Initial AE consultation <30–1 day before consultation | 240 | 1.0 |

| Total children who consulted for AE and MC | 23 049 | 100 |

In the univariate model, children diagnosed with AE were more likely to have a future MC consultation during childhood than controls (OR 1.13; 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.16; P<0.005) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds ratio of molluscum contagiosum consultation in patients with previous atopic eczema diagnosis

| No MC, n | MC, n | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 362 869 | 15 016 | 1.13 | 1.11 to 1.16 | <0.005 |

| Controls | 364 599 | 13 289 |

AE = atopic eczema. MC = molluscum contagiosum. OR = odds ratio.

Corticosteroid potency and type of AE diagnosis did not influence the likelihood of an MC diagnosis (Table 6). However, younger children were more likely to have an MC consultation than older children aged 10–14 years (OR 1.37; 95% CI = 1.32 to 1.42; P<0.005).

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of association of developing molluscum contagiosum within groups of patients with atopic eczema for age, corticosteroid strength, and eczema diagnosisa

| Independent variable | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid potency | |||

| Corticosteroid strength: | |||

| Mild | Ref | ||

| Moderate | 0.37 | 0.10 to 1.50 | 0.16 |

| Potent or very potent | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.06 | 0.17 |

|

| |||

| Age at initial AE diagnosis | |||

| Age group, years: | |||

| <1 | Ref | ||

| 1–4 | 1.37 | 1.32 to 1.42 | <0.005 |

| 5–9 | 1.04 | 0.99 to 1.10 | 0.07 |

| 10–14 | 0.25 | 0.23 to 0.27 | <0.005 |

|

| |||

| AE diagnosis:b | |||

| Primary AE diagnosis | Ref | ||

| Secondary AE diagnosis | 0.89 | 0.83 to 0.94 | <0.005 |

These are independent variables in a single multiple logistic regression model.

Information is available from the author on request. AE = atopic eczema. MC = molluscum contagiosum. OR = odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This large retrospective longitudinal analysis of MC cases presenting to primary care highlights a decline in the rate of primary care consultations between 2004 and 2013 by 50%. The overall consultation rate for children aged 0–14 years was 9.5 per 1000 (95% CI = 9.4 to 9.6), and the age groups with the highest consultation rates were the 1–4 year and 5–9 year age groups (13.1 to 13.0 [males] and 13.0 to 13.9 [females] per 1000 respectively). There was little variation between sexes. In total, 0.8% of patients were referred to a secondary care dermatologist, and the number of referrals annually reduced by 74.4% from 2004 to 2013. A total of 46.6% of consultations resulted in a prescription, with emollients and topical corticosteroids being the most common agents to be prescribed.

The matched cohort study demonstrated that children who have a primary care diagnosis of AE are more likely to have a future MC consultation than age–sex matched controls (OR 1.13; 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.16; P<0.005).

Strengths and limitations

Data were extracted from the CPRD database, which is the largest database of primary care consultations in the UK but is not inclusive of all UK general practices. CPRD data have been subjected to a number of validity assessments and been found to be representative of the UK population.17,18 As with all studies reporting consultation rates of a condition using routinely collected data, this is subject to coding problems and under-ascertainment.19–25 The analysis does not determine causal relationships but describes associations within the data, and although observational studies do not categorically identify ‘cause and effect’ they are important. By identifying associations between MC, age, and AE, this can provide evidence of the aetiology of disease and can lead to more research to explore this further.

This study described children who had an MC diagnosis confirmed and correctly diagnosed by a primary care physician; therefore this will underestimate the true incidence of MC in the community. There is little evidence available of what the prevalence of MC in the community may be. However, because these children do not present to primary care then it can be assumed they are successfully managing the condition.

MC is a self-limiting condition and the 2009 Cochrane review of treatments for cutaneous MC recommends that the condition should be left to resolve naturally.26 In consultations where MC is discussed as a secondary problem, and/or where clinicians are providing only verbal advice and not prescribing treatments, a Read Code for MC may not be entered. Therefore, the study estimates are likely to represent an underestimate of the true incidence of MC consultations. There are also limitations in the correct coding of data held within the CPRD,27 and the use of appropriate coding and confirming a correct diagnosis of MC is unknown. However, by only including ‘up to standard’ data the impact of this source of error has been minimised.

Prescriptions are generally well coded in CPRD, but they are not directly linked to a diagnosis (only linked by consultation). Therefore, it is possible that the medications identified as being linked to MC consultations may actually relate to alternative diagnoses. Given that the most commonly prescribed medications were emollients and topical corticosteroids, associated AE is likely to be the reason for some of the prescribing.

Comparison with existing literature

There are few epidemiological studies of MC conducted in the UK. Two previous studies extracted routinely collected data on consultation rates of MC from a sentinel network of general practices (Weekly Returns Services of the Royal College of General Practitioners) in England and Wales: one from 1994–2003,7 and the other from 2006.6 Both studies found similar consultation rates, the greatest being in children aged 1–4 years (15.0 to 17.2 per 1000).7 Neither of these studies presented data for children aged 5–9 years or 10–14 years, instead merging these into a 5–14-year-old age group. The study data highlight that, when data are analysed in these groups, consultations of MC are greatest in the 1–4 year and 5–9 year age groups (12.8 to 13.7 per 1000). The data also provide a higher rate of consultations in 2004 than that given by Pannell and colleagues in 2005,7 which may be because the current study used more specific and narrower age ranges than those used in previous studies.

Annual trends of MC consultations in the UK were previously reported for the period 1994–2003,7 where the consultation rate rose by 38.5% from 1994–1998 (8 per 1000 to 13 per 1000). The rates remained constant until 2002 and then there was a drop in the rate during 2003. The data from 2004 show a continuation of this decline. The decrease in primary care consultations for MC may be caused by the increased availability of healthcare information online,28 which has resulted in a reduction in parents presenting to primary care if provided with adequate information on health websites.29 A second consideration for the decreasing trends in consultations for MC may be because of true changes in the incidence of infectious disease in developed countries.30 Reasons for reductions in some infectious diseases during the past century may be improved sanitary conditions, less extreme poverty, and a decrease in large numbers of children living in one household. For MC, limited close contact to other children with the condition and improved sanitary conditions could significantly reduce the opportunity for transmission between children and the overall prevalence of the condition in the population.

AE is associated with abnormalities in immune regulation, and patients with AE are known to be more susceptible to a range of cutaneous infections.31 This study is the first to prospectively follow a retrospective cohort in order to determine whether children with a diagnosis of AE have an increased risk of subsequent MC. The study was able to demonstrate that children with AE are 13% more likely to develop MC than children who do not have this diagnosis. Most previous research has also demonstrated an association between AE and MC. A case-control study of children aged ≤5 years identified following outpatient visits in the US found that those with a diagnosis of MC were more likely to have either a current or previous AE diagnosis than controls.15 Another case-control study identified children with MC and compared the prevalence of AE with that of a previous national cross-sectional study. It found a prevalence of 18.2% in the MC cohort and 5% in the national survey.14 Other studies have found a prevalence of AE in children with MC of 24%32 to 43%11 by reviewing the case notes of children attending outpatient clinics. However, one study, in a paediatric outpatient clinic in Brazil, found no difference in the frequency of MC in children with and without AE.12

The association described in this study between children with AE who develop MC may be less than what might have been expected from clinical impressions and what is described in the literature. One reason may be due to coding issues for both conditions, which may under-report the number of children who have a recorded clinical diagnosis of both MC and AE. Improved management of AE could also have contributed to the lower than expected effect size of the association; optimal eczema management has provided rapid improvement in skin barrier function,33 thus reducing the future development of other skin conditions such as MC.

Implications for research and practice

This study has highlighted the association between MC and AE in children; however, currently there is little evidence describing the causes and routes of transmission in the development of MC in children. There is a clear gap in the basic scientific knowledge of MC to provide an understanding of the mechanisms of transmission for healthy children.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Sara Jenkins-Jones for her assistance obtaining CPRD data and Dr Chris Poole for his feedback on the early study protocol.

Funding

This research was funded as part of a postgraduate research studentship by the Cochrane Institute of Primary Care and Public Health/School of Medicine, Cardiff University (Ref: BX1150NF01).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency database research (Ref: 14_058R).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen X, Anstey AV, Bugert JJ. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):877–888. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay JR, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugert JJ. Genus Molluscipoxvirus. In: Mercer AA, Schmidt A, Weber O, editors. Poxviruses: advances in infectious diseases. Basel: Birkhäuser; 2007. pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould D. An overview of Molluscum contagiosum: a viral skin condition. Nurs Stand. 2008;22(41):45–48. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.06.22.41.45.c6577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of Molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(2):190–195. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schofield JK, Fleming D, Grindlay D, Williams H. Skin conditions are the commonest new reason people present to general practitioners in England and Wales. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(5):1044–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pannell RS, Fleming DM, Cross KW. The incidence of Molluscum contagiosum, scabies and lichen planus. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(6):985–991. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805004425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, Francis NA. Epidemiology of Molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):130–136. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes CM, Damon IK, Reynolds MG. Understanding U.S. healthcare providers’ practices and experiences with Molluscum contagiosum. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger EM, Orlow SJ, Patel RR, Schaffer JV. Experience with Molluscum contagiosum and associated inflammatory reactions in a pediatric dermatology practice: the bump that rashes. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(11):1257–1264. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osio A, Deslandes E, Saada V, et al. Clinical characteristics of Molluscum contagiosum in children in a private dermatology practice in the greater Paris area, France: a prospective study in 661 patients. Dermatology. 2011;222(4):314–320. doi: 10.1159/000327888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seize MB, Ianhez M, Cestari Sda C. A study of the correlation between Molluscum contagiosum and atopic dermatitis in children. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4):663–668. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashida S, Furusho N, Uchi H, et al. Are lifetime prevalence of impetigo, Molluscum and herpes infection really increased in children having atopic dermatitis? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;60(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakourou T, Zachariades A, Anastasiou T, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in Greek children: a case series. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(3):221–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCollum AM, Holman RC, Hughes CM, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a pediatric American Indian population: incidence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George J, Majeed W, Mackenzie IS, et al. Association between cardiovascular events and sodium-containing effervescent, dispersible, and soluble drugs: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2013;347:f6954. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood L, Martinez C. The General Practice Research Database: role in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2004;27(12):871–881. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, et al. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(1):4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connell CO, Oranje A, Van Gysel D, Silverberg NB. Congenital Molluscum contagiosum: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(5):553–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohlemeyer CL, Naseer SR. Viral genitourinary tract infections: distinctive features and clinical implications. Pediatr Ann. 1996;25(10):564–570. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19961001-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lio P. Warts, Molluscum and things that go bump on the skin: a practical guide. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2007;92(4):119–124. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.122317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood Molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):503–507. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MA, Singer C. Sexually transmitted viruses other than HIV and papillomavirus. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19(1):47–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trope BM, Lenzi ME. AIDS and HIV infections: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23(6):572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willcox RR. Importance of the so-called ‘other’ sexually-transmitted diseases. Br J Vener Dis. 1975;51:221–226. doi: 10.1136/sti.51.4.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Wouden JC, van der Sande R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Interventions for cutaneous Molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD004767. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004767.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morahan-Martin JM. How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: a cross-cultural review. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7(5):497–510. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray J, Majeed A, Khan MS, et al. Use of the NHS Choices website for primary care consultations: results from online and general practice surveys. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(7):56. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saker L, Lee K, Cannito B, et al. Globalization and infectious diseases: a review of the linkages. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith KJ, Yeager J, Skelton H. Molluscum contagiosum: its clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(9):664–672. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of Molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aalto-Korte K. Improvement of skin barrier function during treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(6):969–972. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]