This phase III trial demonstrated that adding a single dose of fosaprepitant to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and corticosteroid in a nonanthracycline and cyclophosphamide-based moderately emetogenic chemotherapy population significantly improved the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. The use of this regimen may eliminate the need for multiday antiemetic therapy in such patients.

Keywords: fosaprepitant dimeglumine, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, vomiting, nausea, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Abstract

Background

To establish the role of antiemetic therapy with neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonists (RAs) in nonanthracycline and cyclophosphamide (AC)-based moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) regimens, this study evaluated single-dose intravenous (i.v.) fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) associated with non-AC MEC.

Patients and methods

In this international, phase III, double-blind trial, adult cancer subjects scheduled to receive ≥1 non-AC MEC on day 1 were randomized to a regimen comprising single-dose i.v. fosaprepitant 150 mg or placebo along with ondansetron and dexamethasone on day 1; control regimen recipients received ondansetron on days 2 and 3. Primary end points were the proportion of subjects achieving a complete response (CR; no vomiting and no use of rescue medication) in the delayed phase (25–120 h after MEC initiation) and safety. Secondary end points included CR in the overall and acute phases (0–120 and 0–24 h after MEC initiation, respectively) and no vomiting in the overall phase. Nausea and the Functional Living Index-Emesis were assessed as exploratory end points.

Results

The fosaprepitant regimen improved CR significantly in the delayed (78.9% versus 68.5%; P < 0.001) and overall (77.1% versus 66.9%; P < 0.001) phases, but not in the acute phase (93.2% versus 91.0%; P = 0.184), versus control. In the overall phase, the proportion of subjects with no vomiting (82.7% versus 72.9%; P < 0.001) and no significant nausea (83.2% versus 77.9%; P = 0.030) was also significantly improved with the fosaprepitant regimen. The fosaprepitant regimen was generally well tolerated.

Conclusion

Single-dose fosaprepitant added to a 5-HT3 RA and dexamethasone was well tolerated and demonstrated superior control of CINV (primary end point achieved) associated with non-AC MEC. This is the first study to evaluate NK1 RA therapy as an i.v. formulation in a well-defined non-AC MEC population.

ClinicalTrials.gov

NCT01594749 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01594749).

introduction

Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is an important component of cancer treatment management. In the absence of antiemetic prophylaxis, the risk of emesis with antineoplastic agents classified as moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) is 30%–90%, and >90% with highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC). CINV can occur within the acute (0–24 h) or delayed (25–120 h) phases of chemotherapy, with increased severity in the delayed setting [1].

Antiemetic treatment guidelines indicate that 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (RAs) effectively prevent and control CINV during the acute phase in subjects receiving MEC or HEC [2–5], but are generally less effective in preventing CINV in the delayed phase [6, 7]. Aprepitant and fosaprepitant dimeglumine, the water-soluble prodrug that is rapidly converted to aprepitant after intravenous (i.v.) administration, are potent and selective neurokinin-1 (NK1) RAs that are effective against CINV in both acute and delayed phases when added to a standard antiemetic regimen (a 5-HT3 RA and dexamethasone) in subjects receiving HEC and AC-based chemotherapy [8–10]. Although approved for the prevention of MEC- or HEC-associated CINV [11, 12], NK1 RA utility in non-AC MEC recipients has been debated, emphasizing the need for well-designed randomized studies to better define their role in this setting [13].

This study is the first to directly assess the efficacy and safety of a single 150-mg i.v. dose of fosaprepitant combined with a 5-HT3 RA and a corticosteroid versus a standard regimen [5] of 5-HT3 RA plus corticosteroid-alone for the prevention of CINV in a well-defined non-AC MEC population.

methods

study design

This international, phase III, randomized, double-blind, active-comparator, parallel-group, multicenter, superiority trial (PN031) was conducted at 125 sites across 30 countries. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Approval from the independent ethics committee or institutional review board was obtained for each participating center. All subjects provided written informed consent before enrollment.

patients

Subjects aged ≥18 years with confirmed malignant disease, who were treatment naive to MEC and HEC (as defined in the Hesketh classification of emetogenic chemotherapy agents [14]), were eligible. All subjects had to be scheduled to receive ≥1 i.v. dose of MEC on day 1. Combinations of MEC ± a low emetogenic chemotherapy (LEC) were permitted from days 1–3 when part of an overall MEC regimen and were in accordance with current emetogenicity classification guidelines [2, 3]. Although AC regimens have been considered MEC in previous clinical trials, updated treatment guidelines now consider AC regimens to be HEC [2–5]. As a result, AC regimens were not allowed. Minimally emetogenic chemotherapy was permitted throughout the treatment period. Additional cycles of chemotherapy were permitted after the efficacy period.

The major exclusion criteria for this study were vomiting in the 24-h period before day 1, antiemetic use within 48 h of day 1, symptomatic primary or metastatic central nervous system malignancy causing nausea and/or vomiting, and the use of any dose of cisplatin or other HEC.

randomization and blinding

Subjects were randomized (1 : 1) to the single-dose fosaprepitant or control regimen via an interactive voice response system/interactive web response system, and stratified based on sex. Study medications were supplied in a blinded manner as fosaprepitant/placebo i.v. bags, ondansetron/placebo capsules, and dexamethasone/placebo capsules.

study treatments

Subjects received fosaprepitant (fosaprepitant regimen) or placebo (control regimen) on top of ondansetron plus dexamethasone in accordance with current antiemetic guidelines [2, 3, 5] and in agreement with regulatory guidance on the study design (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). For the fosaprepitant regimen, i.v. fosaprepitant as a single 150-mg dose was administered ∼30 min before MEC initiation on day 1. For both regimens, oral ondansetron and oral dexamethasone were taken before MEC on day 1, followed by oral ondansetron 8 h after the first dose. On days 2 and 3, subjects in the control group received ondansetron every 12 h, whereas those in the fosaprepitant group received matching placebo.

The use of investigator-prescribed rescue medication (e.g. 5-HT3 RA, phenothiazines, butyrophenones, benzamides, corticosteroids, benzodiazepines, and domperidone) was permitted throughout the study to alleviate symptoms of established nausea or vomiting.

end points

The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of subjects who achieved complete response (CR; no vomiting and no use of rescue medication) during the delayed phase (25–120 h following initiation of the first MEC dose). Secondary efficacy end points included the proportions of subjects who achieved CR during the overall and acute phases (0–120 and 0–24 h after MEC initiation, respectively) and the proportion of subjects with no vomiting (regardless of rescue medication use) during the overall phase. A list of exploratory end points assessed in this study is provided in supplementary Materials, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Clinical adverse events (AEs) were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 4.0. Infusion-related reactions, including infusion-site thrombophlebitis and severe infusion-site pain, erythema, and induration, were prespecified as events of clinical interest. Additionally, vomiting was reported as an AE if the vomiting episode occurred outside of the efficacy assessment period or met criteria for a serious adverse event (SAE).

statistical analysis

Statistical methods are described in supplementary Materials, available at Annals of Oncology online.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population (subjects receiving ≥1 dose of study drug and analyzed in their randomized treatment group) was used for the primary efficacy analysis, whereas the all-subjects-as-treated (ASaT) population (all subjects receiving ≥1 dose of study drug and analyzed in the treatment group based on the drug actually received) was used for the safety analysis.

Treatment comparisons for the primary and secondary efficacy analyses included formal tests for superiority using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, stratified by sex. Superiority of the fosaprepitant versus the control regimen was evaluated using a two-tailed test with P ≤ 0.05 indicating a significant difference. No formal test of superiority was carried out for exploratory end points.

Descriptive statistics were provided for demographic variables, baseline characteristics, and AEs. Details on the analyses of exploratory end points and AEs are provided in supplementary Methods and Results, available at Annals of Oncology online.

results

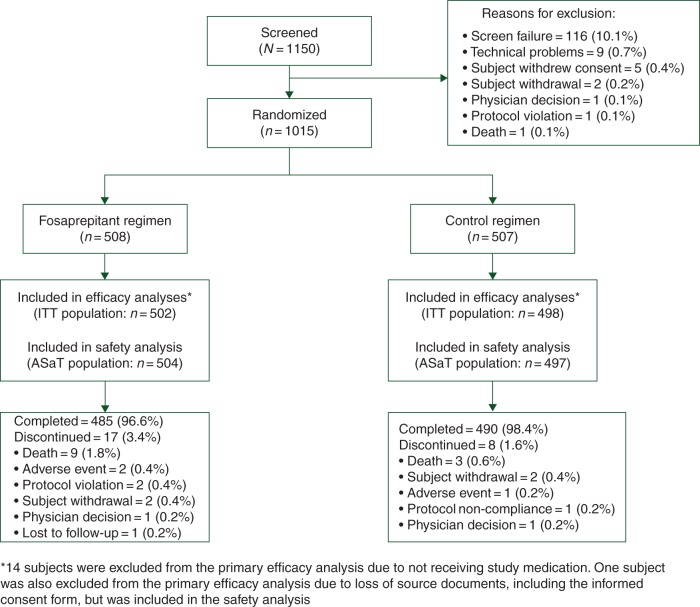

Overall, 1015 of the 1150 screened subjects were randomized between 30 October 2012 and 03 November 2014. Reasons for nonrandomization are shown in Figure 1. The ITT and ASaT populations comprised 1000 and 1001 subjects, respectively (Figure 1). The overall mean age was 59.6 years. Baseline demographics of the ITT population (Table 1) were similar between treatment groups and balanced with respect to the malignancy type being treated, which were representative of a MEC population. Treatment groups were also balanced regarding the types of chemotherapy regimens used, with most subjects receiving single-day regimens (71.3% and 69.9% for fosaprepitant and control regimens, respectively; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Chemotherapeutic agents administered were balanced, with carboplatin (∼53%) and oxaliplatin (∼22%) most commonly used in both treatment groups (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Overall, 96.6% and 98.4% of subjects completed the study in the fosaprepitant and control groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. ASaT, all subjects as treated; ITT, intent-to-treat.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and specific clinical characteristics (ITT population)

| Fosaprepitant regimen (N = 502) | Control regimen (N = 498) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age [mean (SD)], years | 60.0 (11.8) | 59.1 (12.3) |

| Age <50 years, n (%) | 97 (19.3) | 108 (21.7) |

| Age ≥50 years, n (%) | 405 (80.7) | 390 (78.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 204 (40.6) | 205 (41.2) |

| Female | 298 (59.4) | 293 (58.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 424 (84.5) | 414 (83.1) |

| Asian | 21 (4.2) | 14 (2.8) |

| Black or African American | 13 (2.6) | 8 (1.6) |

| Other | 44 (8.8) | 62 (12.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 89 (17.7) | 102 (20.5) |

| Type of malignancy, n (%) | ||

| Lung | 129 (25.7) | 125 (25.1) |

| Breast | 110 (21.9) | 121 (24.3) |

| Colorectal | 102 (20.3) | 91 (18.3) |

| Gynecologic | 81 (16.1) | 71 (14.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | 33 (6.6) | 41 (8.2) |

| Head and neck | 12 (2.4) | 9 (1.8) |

| Other | 35 (7.0) | 40 (8.0) |

| History of motion sickness, n (%) | 28 (5.6) | 30 (6.0) |

| History of emesis during pregnancy, n (%) | 60 (12.0) | 61 (12.2) |

| History of alcohol use, n (%) | 224 (44.6) | 213 (42.8) |

ITT, intent to treat; SD, standard deviation.

efficacy

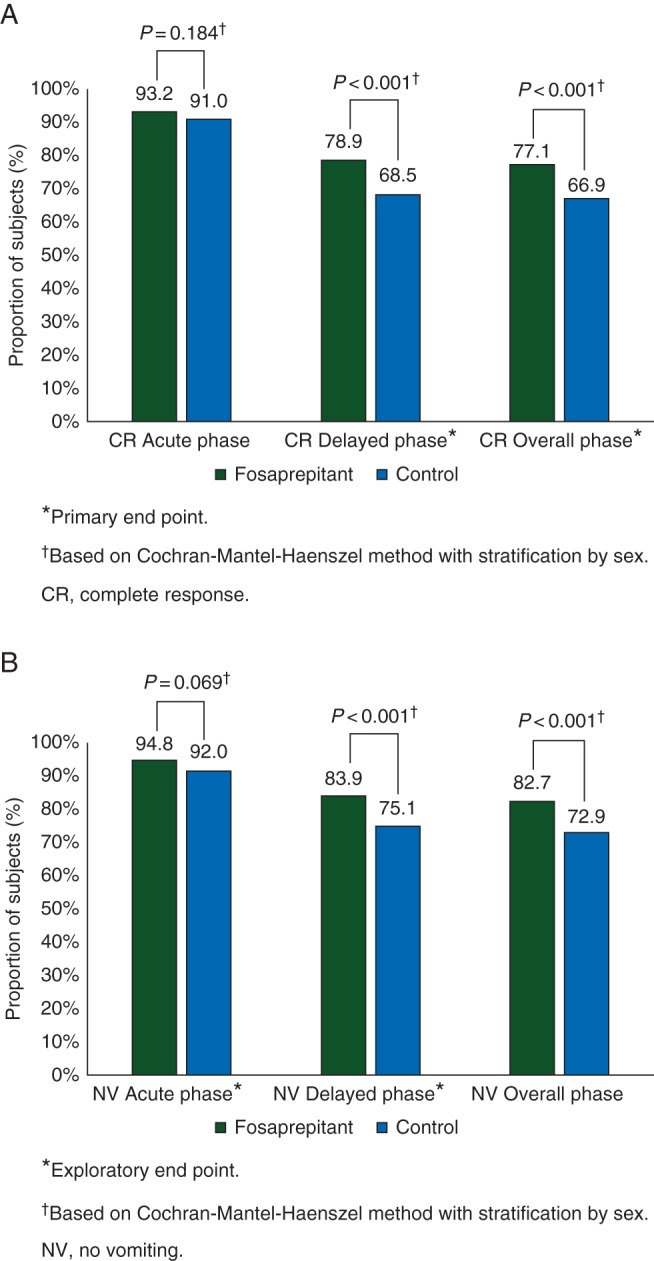

CR in the delayed phase (primary end point) was superior in the fosaprepitant versus the control regimen (treatment difference 10.4%; P < 0.001) (Figure 2A); this was also consistent in the full analysis set and per-protocol populations (defined in supplementary Materials, available at Annals of Oncology online). CR during the overall phase was also superior in the fosaprepitant regimen (treatment difference 10.2%; P < 0.001). Both regimens had a high CR in the acute phase (treatment difference 2.3%; P = 0.184).

Figure 2.

Proportion of subjects with (A) complete response (CR) and (B) no vomiting in the acute (0–24 h), delayed (25–120 h), and overall (0–120 h) phases following initiation of a first dose of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

Fosaprepitant regimen was superior to the control regimen for no vomiting in the overall phase (treatment difference 9.8%; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). The exploratory end point of no vomiting in the delayed phase was also superior in the fosaprepitant group (treatment difference 8.8%; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the estimated time-to-first vomiting episode in the overall phase, regardless of rescue medication use, was longer in the fosaprepitant group, compared with the control group (nominal P < 0.001) (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The proportion of subjects with no significant nausea was significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group in the overall phase (83.1% versus 78.3%, P = 0.026), but between-group differences in the proportions of subjects with no nausea or no rescue medication use did not reach statistical significance (65.3% versus 61.6%, P = 0.156 and 83.9% versus 79.5%, P = 0.069, respectively).

The proportion of subjects with no impact of CINV on daily life [Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) total score >108] was significantly greater for the fosaprepitant versus the control group [81% versus 75.5%; odds ratio 1.39; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.91; P = 0.043]. Similar results were observed for individual FLIE domains, with the exception of the vomiting-specific domain (nominal P = 0.068).

safety and tolerability

AEs were reported by 61.3% of subjects in the ASaT population and were comparable between the treatment regimens (Table 2). The AE profile was generally typical of a population receiving emetogenic chemotherapy. The most commonly reported all-grade AEs for the fosaprepitant and control groups were fatigue, diarrhea, and constipation (Table 2). No cases of severe infusion-site pain, erythema, or induration were reported. Three cases (0.6%) of infusion-site thrombophlebitis were reported in the fosaprepitant group, compared with no cases in the control group (treatment difference 0.6%; 95% CI −0.2 to 1.7; P = 0.085); none of these infusion-site reactions were considered by the investigator to be severe or related to study medication.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events (all-subjects-as-treated population)a

| N (%) | Fosaprepitant regimen (N = 504) | Control regimen (N = 497) | Difference versus control regimen, % (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 AE | 312 (61.9) | 302 (60.8) | 1.1 (−4.9 to 7.2) |

| Drug-related AEsc | 43 (8.5) | 45 (9.1) | −0.5 (−4.1 to 3.0) |

| Serious AEs | 39 (7.7) | 35 (7.0) | 0.7 (−2.6 to 4.0) |

| Serious drug-related AEsc | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | −0.2 (−1.3 to 0.7) |

| Deathd | 8 (1.6) | 2 (0.4) | 1.2 (−0.1 to 2.7) |

| Discontinuatione due to AE | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | −0.0 (−1.1 to 1.1) |

| Commonly reported AEs (≥5% of subjects) | |||

| Fatigue | 76 (15.1) | 64 (12.9) | 2.2 (−2.1 to 6.5) |

| Diarrhea | 64 (12.7) | 56 (11.3) | 1.4 (−2.6 to 5.5) |

| Constipation | 47 (9.3) | 52 (10.5) | −1.1 (−4.9 to 2.6) |

| Neutropenia | 41 (8.1) | 37 (7.4) | 0.7 (−2.7 to 4.1) |

| Headache | 30 (6.0) | 35 (7.0) | −1.1 (−4.2 to 2.0) |

| Decreased appetite | 27 (5.4) | 32 (6.4) | −1.1 (−4.1 to 1.9) |

| Alopecia | 11 (2.2) | 26 (5.2) | −3.0 (−5.6 to −0.7) |

aOne cross-treated subject was randomized to the control group but received fosaprepitant in error; this subject was included in the fosaprepitant group for safety and the control group for efficacy. One subject with missing informed consent received fosaprepitant and was included in the fosaprepitant safety group.

bBased on Miettinen and Nurminen method.

cDetermined by the investigator to be related to any of the study drugs.

dDeaths resulting from AEs that had an onset date between the baseline and safety follow-up period (i.e. days 1–17, inclusive).

eStudy medication withdrawn.

AE: adverse event; CI: confidence interval.

Most AEs were grade 1–2 in severity, with neutropenia being the most commonly reported grade 3–4 AE in both the fosaprepitant and control groups (5.2% versus 4.8%).

Overall, SAEs were reported in 74 subjects (7.4%); the most commonly reported was febrile neutropenia (1.6% and 1.0% of fosaprepitant and control regimen recipients, respectively). Drug-related SAEs were reported in one and two subjects receiving the fosaprepitant (hypersensitivity reaction) and control (one worsening constipation; one allergic reaction) regimens, respectively. Sixteen randomized subjects died, with the day of death relative to treatment day 1 ranging from day 4 to 90. Of these subjects, 10 had AEs with an onset date that occurred between day 1 (baseline) and day 17 (14 days after the last dose of study medication), inclusive, that resulted in death (Table 2). All cases appeared to be attributable to subjects' underlying malignancy, other pre-existing conditions, and/or effects of chemotherapy; no deaths were considered by investigators to be related to the study drug.

discussion

This is the first study to provide efficacy and safety data on a single 150-mg i.v. dose of fosaprepitant added to a 5-HT3 RA and a corticosteroid for the prevention of CINV in adults receiving non-AC MEC. Overall, this single-day, triple-antiemetic fosaprepitant regimen proved to be superior to a standard 3-day control antiemetic regimen for the prevention of CINV associated with MEC.

The superior results in the delayed and overall phases were similar to those of previous NK1 RA clinical trials in subjects receiving HEC [8–10, 15–18]. Furthermore, consistent with antiemetic guidelines, treatment differences of >10% in favor of the fosaprepitant regimen for CR (delayed and overall phases) in the current study are considered to be clinically meaningful for patients [1, 3].

In contrast to previous studies, the fosaprepitant regimen did not improve CR during the acute phase. This may be attributed in part to a higher than expected CR rate (92%) in the acute phase of the control group compared with that of previous studies (49%–85%) [8–10, 15, 16, 18]. Differences in study populations may have been a factor; subjects in previous studies primarily received cisplatin or AC-based MEC regimens [8–10, 15, 16, 18], which are now classified as HEC under current treatment guidelines [2, 5]. Post hoc analysis of a phase III trial consisting of a broad range of MEC (AC and non-AC regimens) reported CR improvements with an aprepitant regimen in subjects receiving non-AC MEC [17]. Another phase III trial also reported CR improvements with the NK1 RA, rolapitant, in a large MEC population stratified based on AC and non-AC regimens; >50% of subjects in the study received AC-based regimens [19].

To our knowledge, this is the first large, global, randomized, controlled superiority trial to prospectively evaluate treatment with a single-dose i.v. NK1 RA in a well-characterized non-AC MEC population.

The fosaprepitant regimen also provided significant improvements in the secondary and exploratory efficacy end points, such as no vomiting in the overall and delayed phases, no significant nausea in the overall phase, and improved quality of life, consistent with previous NK1 RA trials [8–10, 15, 17, 18]. Taken together, the overall efficacy findings support the clinical benefit provided by the fosaprepitant regimen in a non-AC MEC population.

The fosaprepitant regimen was generally well tolerated in the current study, and no new safety signals were noted compared with previous fosaprepitant studies [15, 20]. AE profiles for the two treatment regimens were similar and consistent with those in subjects receiving emetogenic chemotherapy [21]. An imbalance in deaths between the treatment arms was observed, but a careful review of each case suggested that these were likely to reflect progression of the underlying disease process, and no deaths were assessed as likely to be related to the study drug by the investigators. Finally, although higher infusion-site AE rates have been previously observed with fosaprepitant [15, 20, 22], only three cases of infusion-site thrombophlebitis were reported in the fosaprepitant group for this study.

This study included a large, well-balanced non-AC MEC population regarding the types of chemotherapy regimens and agents administered. While these findings indicate that a single-dose fosaprepitant regimen can potentially offer the convenience of completing all antiemetic treatment before MEC initiation in a single day, the study was not designed to evaluate treatment differences among subgroups across the full heterogeneity of the MEC population. Unlike HEC regimens, which are generally homogeneous in terms of emetogenic potential (>90%), the risk of emesis in MEC populations ranges from 30% to 90% and is complicated by factors such as chemotherapy sequence and dosing, as well as multiday treatment regimens [2–5]. However, in this trial, the majority of subjects received a single-day, non-AC MEC regimen by design, with carboplatin being the most commonly used MEC agent. Although less emetogenic than the classic HEC agent, cisplatin, carboplatin is likely to be in the ‘upper end’ of the current MEC emetogenicity classification. Additionally, MEC–LEC combination regimens may increase the risk of emesis versus MEC or LEC alone. Antiemetic guidelines advise that additional antiemetic treatment may be needed for chemotherapy regimens that extend beyond day 1 because the risk periods for acute and delayed emesis overlap after the first day of chemotherapy [2, 3]. The role of NK1 RA, such as i.v. fosaprepitant, in the non-AC MEC setting may be better defined through additional subgroup analyses of this study population to identify specific MEC subpopulations that are more likely to respond to antiemetic treatment and to determine whether additional prophylactic antiemetic treatment is warranted for multiday chemotherapy regimens. While it is recognized that additional studies may be needed to fine-tune future antiemetic guidelines within the heterogeneous MEC population (e.g. exploring differences between carboplatin and noncarboplatin-containing regimens and between single-day versus multiday antiemetic regimens), our findings clearly demonstrate the benefit of fosaprepitant for the prevention of CINV in a well-defined MEC population. This adds to the available evidence for aprepitant in non-AC-based MEC regimens [17], and suggests that the role of adding an NK1 RA in the overall MEC setting, such as aprepitant/fosaprepitant, in all antiemetic guidelines warrants further discussion.

funding

This study was not supported by a grant. This work was supported by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

disclosure

CW is an employee and stockholder of Merck & Co., Inc. KJ has received honoraria for consultancy from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Merck & Co., Inc., Helsinn, and Pro-Strakan. SG, EBB, and WV are employees and stockholders of Merck & Co., Inc., and LWL is an employee of Merck & Co., Inc. SN has received honoraria from Millenium and served as a consultant or in an advisory role for Amgen and Millenium (now Takeda Oncology). BLR has served as a consultant or in an advisory role for and has received payment for travel, accommodations, or expenses from MSD and Tesaro. BLR has also received payments for participation on speakers bureaus for MSD and Roche.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank Lydia Kevill for assisting with study supervision and data collection. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Maxwell Chang and Traci Stuve of ApotheCom, Yardley, PA, USA, with funding provided by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

references

- 1.Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol 2010; 21(suppl 5): v232–v243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Antiemesis. Version 1.2014. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Web site; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gralla RJ, Roila F, Tonato M, Herrstedt J. MASCC/ESMO antiemetic guideline 2013. Hillerød, Denmark: Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan K, Gralla R, Jahn F, Molassiotis A. International antiemetic guidelines on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): content and implementation in daily routine practice. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722: 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4189–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR et al. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-receptor antagonists versus prochlorperazine for control of delayed nausea caused by doxorubicin: a URCC CCOP randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2005; 6: 765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geling O, Eichler HG. Should 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists be administered beyond 24 hours after chemotherapy to prevent delayed emesis? Systematic re-evaluation of clinical evidence and drug cost implications. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1289–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ et al. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin—the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 4112–4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD et al. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer 2003; 97: 3090–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2822–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prescribing information. Emend (Aprepitant) Capsules, for Oral use. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prescribing information. Emend (Fosaprepitant Dimeglumine) for Injection, for Intravenous use. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan K, Jahn F, Aapro M. Recent developments in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a comprehensive review. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Grunberg SM et al. Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saito H, Yoshizawa H, Yoshimori K et al. Efficacy and safety of single-dose fosaprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gralla RJ, de Wit R, Herrstedt J et al. Antiemetic efficacy of the neurokinin-1 antagonist, aprepitant, plus a 5HT3 antagonist and a corticosteroid in patients receiving anthracyclines or cyclophosphamide in addition to high-dose cisplatin: analysis of combined data from two phase III randomized clinical trials. Cancer 2005; 104: 864–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapoport BL, Jordan K, Boice JA et al. Aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with a broad range of moderately emetogenic chemotherapies and tumor types: a randomized, double-blind study. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18: 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aapro M, Rugo H, Rossi G et al. A randomized phase 3 study evaluating the efficacy and safety of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnadig ID, Modiano MR, Poma A et al. Phase 3 trial results for rolapitant, a novel NK-1 receptor antagonist, in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in subjects receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(5 suppl): abstr 9633. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunberg S, Chua D, Maru A et al. Single-dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with cisplatin therapy: randomized, double-blind study protocol—EASE. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gralla RJ, Bosnjak SM, Hontsa A et al. A phase III study evaluating the safety and efficacy of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over repeated cycles of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1333–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leal AD, Kadakia KC, Looker S et al. Fosaprepitant-induced phlebitis: a focus on patients receiving doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide therapy. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22: 1313–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.