In patients with transfusion-dependent, lower-risk, del(5q) myelodysplastic syndromes, lenalidomide effectively reduces red blood cell transfusion burden and acts as a disease-modifying agent, altering the natural history of the disease by suppressing the del(5q) clone. Hematologic and/or cytogenetic responses correlate with delayed acute myeloid leukemia progression and better overall survival.

Keywords: lenalidomide, myelodysplastic syndromes, deletion 5q

Abstract

The treatment of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) begins with assessment of karyotype and risk. Lenalidomide is approved for the treatment of patients who have transfusion-dependent anemia due to lower-risk MDS with chromosome 5q deletion (del(5q)) with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities, and isolated del(5q) only in the European Union. Mounting evidence suggests that lenalidomide is effective not only in reducing red blood cell (RBC) transfusion burden, but also in modifying the disease natural history by suppressing the malignant clone. Data discussed here from the pivotal phase 2 (MDS-003) and phase 3 (MDS-004) studies of lenalidomide demonstrate that lenalidomide treatment was associated with both short- and long-term benefits. These clinical benefits included high rates of RBC-transfusion independence (TI) with prolonged durations of response, high rates of cytogenetic response (CyR) associated with achievement of durable RBC-TI, no significant difference in rates of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Achievement of RBC-TI and CyR with lenalidomide treatment was associated with extended survival and time to AML progression. Achievement of RBC-TI and hemoglobin response was additionally associated with HRQOL benefits. Recent data describing the impact of TP53 mutations and p53 expression on the prognosis of patients with del(5q) and the impact on response to lenalidomide are also discussed. The authors provide practical recommendations for the use of lenalidomide in patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS.

introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) include a spectrum of myeloid malignancies characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis resulting in peripheral blood cytopenias, recurring cytogenetic abnormalities, and risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [1–3]. Anemia is the most common cytopenia and negatively impacts survival and quality of life [4–8]. By the 2008 World Health Organization criteria, MDS are classified into subtypes based on the percentage of blasts in the bone marrow and/or peripheral blood, morphological findings, cytopenias, and cytogenetic abnormalities [9]. A chromosome 5q deletion (del[5q]), either isolated or accompanied by additional cytogenetic abnormalities, is the most commonly detected chromosomal abnormality in MDS, reported in 10%–30% of patients [3, 10–12]. The treatment of MDS is broadly based on assessment of risk, with differing strategies for patients with a lower- or higher-risk disease [13]. The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) is a widely used risk assessment tool [6] that stratifies patients into four risk groups based on cytogenetics, the percentage of bone marrow blasts, and the number of cytopenias [14]. The IPSS was revised (IPSS-R) to incorporate expanded cytogenetic categories, greater discrimination in bone marrow blast thresholds, and severity of cytopenias [6].

Lenalidomide is approved for the treatment of transfusion-dependent (TD) anemia in patients with IPSS low– or intermediate-1–risk (Int-1–risk) MDS with del(5q) with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities (in the United States) [15]; or isolated del(5q) when other therapeutic options are insufficient or inadequate (in the European Union) [16]. The efficacy of lenalidomide in such TD patients has been evaluated in two pivotal trials. MDS-003 was a phase 2, multicenter, single-arm study (N = 148) in which patients received 10 mg lenalidomide on days 1–21 of 28-day cycles or with daily dosing [17]. MDS-004 was a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (N = 205) in which patients were randomly assigned 1 : 1 : 1 to receive 10 mg lenalidomide on days 1–21 of 28-day cycles, 5 mg lenalidomide daily, or placebo daily [18]. Patients without at least minor erythroid response by week 16 were discontinued from the double-blind phase and eligible for open-label treatment with lenalidomide. The utility of the IPSS-R was also recently validated in lenalidomide-treated patients with del(5q) lower-risk MDS, with a significantly reduced duration of transfusion independence (TI) and overall survival (OS) associated with an increasing score [19].

Mounting evidence suggests that lenalidomide is effective not only at reducing red blood cell (RBC) transfusion burden, but also as a disease modifier, altering the natural history of the disease by suppressing the del(5q) clone, resulting in cytogenetic responses (CyRs) and accompanied by a corresponding reduction in the risk of AML progression and extension of survival [17, 18, 20–22]. In this article, we review the results supporting the short- and long-term benefits of lenalidomide treatment in patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS and discuss the complex interplay between these outcomes. We will also highlight recent data describing the potential impact of TP53 mutations and p53 expression on the short- and long-term outcomes of lenalidomide treatment.

key short-term outcomes

Treatment with lenalidomide results in high rates of RBC-TI and CyR in RBC-TD patients with lower-risk MDS with del(5q) (Table 1) [17, 18, 20, 21]. In MDS-003, 67% of patients achieved RBC-TI ≥8 weeks, with a median time to onset of 4.6 weeks and a median peak hemoglobin rise of 5.4 g/dl [17]. With long-term follow-up (median 3.2 years), the median duration of response to lenalidomide was 2.2 years [20]; median duration of response was 2.3 years in patients with isolated del(5q) compared with 2.0 years in patients with greater cytogenetic complexity (P = 0.020). In MDS-004, 56% and 43% of patients treated with lenalidomide 10 and 5 mg, respectively, achieved RBC-TI ≥26 weeks versus 6% of those treated with placebo (P < 0.001 versus both lenalidomide groups; Table 1) [18]. Among patients treated with 10 or 5 mg lenalidomide who achieved RBC-TI ≥26 weeks, the onset of response occurred during cycle 1 for 49% of patients and within the first four cycles among the remaining patients. Similar results were seen for achievement of RBC-TI ≥8 weeks (Table 1), and the median peak hemoglobin increases were 6.3 and 5.2 g/dl for patients treated with lenalidomide 10 or 5 mg, respectively [18]. The median durations of International Working Group 2000-defined (RBC-TI ≥8 weeks) [23] and protocol-defined (RBC-TI ≥26 weeks) erythroid responses were not reached [18].

Table 1.

Short-term outcomes with LEN treatment

| Outcome | MDS-003 study [17] | MDS-004 study [18] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mga (N = 148) | LEN 10 mgb (N = 41) | LEN 5 mgc (N = 47) | Placeboc (N = 51) | |

| RBC-TI ≥8 weeks (IWG 2000 [23]), n (%) | 99 (67) | 25 (61)d | 24 (51)d | 4 (8) |

| Median peak Hb increase, g/dl (range) | 5.4 (1.1–11.4) | 6.3 (1.8–10.0) | 5.2 (1.5–8.5) | NA |

| RBC-TI ≥26 weeks, n (%) | NA | 23 (56)d | 20 (43)d | 3 (6) |

| Cytogenetic response, % | 73e | 50d | 25d | 0 |

| Complete cytogenetic response | 45e | 29d | 16d | 0 |

aThe first 46 patients were treated on days 1–21 of 28-day cycles, and following a protocol amendment, 102 patients received continuous daily dosing.

bDays 1–21 of 28-day cycles.

cContinuous daily dosing.

dP < 0.001 versus placebo.

eOf 85 patients evaluable.

Hb, hemoglobin; IWG, International Working Group; LEN, lenalidomide; NA, not available; RBC-TI, red blood cell transfusion independence.

In MDS-003, 73% of assessable patients achieved a CyR, including 45% with a complete CyR [17]. In MDS-004, the corresponding rates of CyR were 50% with lenalidomide 10 mg and 25% with lenalidomide 5 mg, including 29% and 16% with complete CyRs, respectively [18]. No patients in the placebo group achieved CyR (P < 0.001 versus both lenalidomide groups) [18]. A recent pooled analysis of 181 lenalidomide-treated patients from MDS-003 and MDS-004 showed a strong relationship between achievement of RBC-TI ≥26 weeks and CyR [21]. A higher rate of patients who achieved RBC-TI ≥26 weeks also achieved CyR compared with those who did not achieve RBC-TI (71% versus 31%, a 2.3-fold increase in CyR, P < 0.001). Conversely, 82% of patients with CyR achieved RBC-TI ≥26 weeks. Additionally, rates of CyR were more than double in patients treated with 10 versus 5 mg lenalidomide (65% versus 30%, P < 0.001) [21].

Although it is clear that lenalidomide targets the del(5q) clone to induce CyR, evidence suggests that it does so by suppressing the del(5q) clone rather than eradicating it. For example, in a study of seven patients with MDS with del(5q) who became TI and achieved partial or complete CyR with lenalidomide, their bone marrow specimens were examined to assess the impact on the del(5q) clone [24]. In all seven patients, a dramatic reduction in progenitor cells was seen with achievement of TI (mean reduction to 10% of baseline levels; three patients had no detectable del(5q) progenitor cells). A reduced proportion of stem cells with del(5q) was also detected in all patients, but to a lesser degree (mean reduction to 45% of baseline levels). The proportion reduction of progenitor versus stem cells with lenalidomide treatment was significant (P = 0.003).

key long-term outcomes

Treatment with lenalidomide results in a median OS of >3 years in TD patients and does not increase the risk of progression to AML (Table 2) [18, 20, 22]. In MDS-003, the median OS was 3.3 years [20]. In MDS-004, a similar median OS of 3.7 and ≥3.0 years were reported for treatment with lenalidomide 10 and 5 mg, respectively [18]. A retrospective analysis compared lenalidomide-treated patients from MDS-003 and MDS-004 (n = 295) with untreated patients with RBC-TD IPSS low– or Int-1–risk MDS with del(5q) from nine MDS registries matched for risk and TD (n = 125) [22]. The median OS from diagnosis was 5.2 years for lenalidomide-treated patients versus 3.8 years for untreated patients (P = 0.755) [22]. By multivariate analysis with left truncation to correct for person-time at-risk due to different starting points of patient follow-up (first lenalidomide dose in the lenalidomide cohort versus date of diagnosis in the untreated cohort), lenalidomide treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death versus no lenalidomide treatment (P = 0.012) [22].

Table 2.

Long-term outcomes with LEN treatment

| Outcome | MDS-003 study [20] |

MDS-004 study [18] |

Retrospective analysis [22] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mga (N = 148) | LEN 10 mgb (N = 41) | LEN 5 mgc (N = 47) | Placeboc (N = 51) | LEN-treated (N = 295)d | Untreated (N = 125)e | |

| Median follow-up, years | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| Median OS, years (95% CI) | 3.3 (2.7–3.9) | 3.7 (3.0–NR) | ≥3.0 (2.1–NR) | 3.5 (2.7–NR) | 5.2 (4.5–5.9)f | 3.8 (2.9–4.8)f |

| Cumulative risk of progression to AML, % | ||||||

| 1 year | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2 year | NA | 17 | NA | 7 | 12 | |

| 3 year | NA | 25 | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5 year | 29 | NA | NA | 23 | 20 | |

aThe first 46 patients were treated on days 1–21 of 28-day cycles, and following a protocol amendment, 102 patients received continuous daily dosing [17].

bDays 1–21 of 28-day cycles.

cContinuous daily dosing.

dLEN-treated patients from MDS-003 and MDS-004.

ePatients with red blood cell transfusion-dependent International Prognostic Scoring System low– or intermediate-1–risk MDS with del(5q) pooled from nine MDS registries.

fMedian OS from diagnosis.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; LEN, lenalidomide; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; NA, not available; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival.

In MDS-003, the cumulative 1- and 5-year risks of progression to AML were 7% and 29%, respectively [20]. In MDS-004, the cumulative 2- and 3-year risks of progression to AML were 17% and 25% for both lenalidomide treatment groups combined [18]. In the pooled retrospective analysis of lenalidomide-treated patients from MDS-003 and MDS-004 versus untreated registry patients with RBC-TD IPSS low– or Int-1–risk MDS with del(5q), the cumulative 2- and 5-year risks of progression to AML were 7% and 23% with lenalidomide versus 12% and 20% with no treatment [22]. By multivariate analysis with left truncation, lenalidomide treatment was not associated with an increased risk of progression to AML (P = 0.930) [22].

associations between short- and long-term outcomes

Separate 6-month landmark analyses of MDS-003 and MDS-004 demonstrated that achievement of RBC-TI or CyR with lenalidomide treatment is associated with prolonged survival and time to AML progression (Table 3) [18, 20, 21]. Patients who achieved RBC-TI ≥8 weeks with lenalidomide versus those who did not exhibited significantly prolonged OS (MDS-003, P < 0.0001; MDS-004, P = 0.0028) [18, 20], AML-free survival (MDS-004, P = 0.0085) [18], and time to progression to AML (MDS-003, P = 0.001) [20]. However, time to progression to AML in patients who achieved RBC-TI ≥8 weeks with lenalidomide versus those who did not in MDS-003 was no longer significant (P = 0.174) when death was analyzed as a competing risk [20]. Multivariate analyses of the 6-month landmark analyses showed that achievement of RBC-TI ≥8 weeks with lenalidomide was associated with a reduced relative risk of death (MDS-003, 73% reduction, P < 0.001; MDS-004, 47% reduction, P = 0.021) [18, 20] and a reduced relative risk of progression to AML or death (MDS-004, 42% reduction, P = 0.048) [18], with a trend toward a reduced relative risk of progression to AML (MDS-003, 56% risk reduction, P = 0.080) [20]. Patients who achieved CyR with lenalidomide versus those who did not exhibited prolonged OS (MDS-003, P = 0.010; MDS-004, P = 0.0732) [18, 20] and time to AML progression (MDS-003, P = 0.002) [20]. Time to AML progression for patients who achieved CyR versus those who did not in MDS-003 remained significant (P = 0.012) when death was analyzed as a competing risk [20]. The probability of progression to AML was not significantly different between patients who achieved CyR versus those who did not in the MDS-004 study (P = 0.5086) [18].

Table 3.

Six-month landmark analyses of the MDS-003 and MDS-004 studies

| Outcome | MDS-003 study [20] |

MDS-004 studya [18] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | No response | P-value | Response versus no response P-value | |

| RBC-TI ≥8 weeks (IWG 2000 [23]) | ||||

| Median OS, years | 4.3 | 2.0 | <0.0001 | 0.0028 |

| Median AML-free survival, years | NA | NA | NA | 0.0085 |

| Median time to progression to AML, years | NR | 5.2 | 0.001 | NA |

| CyR | ||||

| Median OS, years | 4.9 | 3.1 | 0.010 | 0.0732 |

| Median time to progression to AML, years | NR | 3.8 | 0.002 | NA |

aOnly P-values were reported in the MDS-004 study.

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CyR, cytogenetic response; IWG, International Working Group; LEN, lenalidomide; NA, not available; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; RBC-TI, red blood cell transfusion independence.

In the pooled analysis of 181 patients from MDS-003 and MDS-004, AML-free survival was significantly prolonged in patients with CyR versus no CyR for those with isolated del(5q) (n = 130; median 59.9 versus 36.7 months, P = 0.0042) and del(5q) +1 additional cytogenetic abnormality (n = 32; median 58.1 versus 30.7 months, P = 0.0259) [21]. No difference was observed for patients with a complex karyotype (del(5q) +≥2 additional abnormalities), although the sample size was small (n = 14; median 20.5 versus 14.7 months, P = 0.8257) [21]. Achievement of CyR with lenalidomide was also significantly associated with AML-free survival by multivariate analysis (P = 0.001), as was total cumulative lenalidomide dose in treatment cycle 1 (P = 0.045) [21].

impact of TP53 mutations and p53 expression on outcome of lenalidomide treatment

Evidence from laboratory studies and murine models suggests that pathogenesis of the anemia in patients with del(5q) MDS arises in part from stabilization of p53 in erythroid precursors secondary to ribosomopathy, resulting in increased apoptosis and erythroid hypoplasia [25]. Mutations in the TP53 gene have been identified in approximately one-fifth to one-quarter of patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS [26, 27] and have been associated with both lower rates of CyR with lenalidomide treatment [27] and poor OS (independent factor, with adjustment for IPSS risk group) regardless of treatment [28]. Lenalidomide has been shown to promote degradation of p53 in erythroid precursors [29]. In the bone marrow of responding patients, lenalidomide treatment resulted in significant reductions of p53 expression in erythroid precursors compared with that in normal controls (P = 0.04). However, in patients who became refractory to lenalidomide, p53 expression was increased more than threefold at the time of lenalidomide treatment failure (P = 0.003) [29].

Jädersten et al. [26] carried out next-generation sequencing for TP53 mutations in 55 patients with del(5q) lower-risk MDS. TP53 mutations with a median clone size of 11% were detected in 10 patients (18%) at an early stage [26]. Mutations were associated with evolution to AML (5 of 10 patients with TP53 mutations versus 7 of 45 patients without; P = 0.045). Nine of 10 patients carrying mutations showed >2% of bone marrow progenitors with strong p53 nuclear staining [26]. The probability of a complete CyR to lenalidomide was lower in patients with TP53 mutations (0 of 7 versus 12 of 24; P = 0.024) [26]. A recent study examined p53 expression levels and TP53 mutations in bone marrow samples from 85 patients in the MDS-004 trial and found that 35% of patients had strong p53 expression, defined as staining in ≥1% of their bone marrow progenitors at baseline [30]. Patients with strong p53 expression had a significantly lower rate of CyR (P = 0.009), shorter OS (P = 0.0175), and higher risk of progression to AML (P = 0.0006) versus those who did not. Strong p53 expression was not associated with decreased rates of achievement or duration of RBC-TI ≥26 weeks. By multivariate analysis, p53 expression was a strong independent predictor of transformation to AML (P = 0.0035) [30]. Of nine patients screened for mutations, TP53 mutations were detected in three patients and cellular TP53 mutation burden was strongly correlated with strength of p53 expression [30]. Thus, p53 expression—or more importantly, TP53 gene mutations—may be a useful tool for risk assessment and clinical decision-making for patients with lower-risk MDS eligible for treatment with lenalidomide.

key short- and long-term safety outcomes

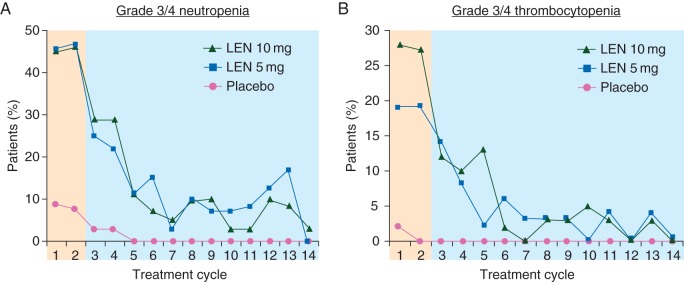

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) reported with lenalidomide treatment of lower-risk del(5q) MDS are cytopenias (Table 4) [17, 18]; as mentioned previously, treatment-related cytopenias may be a result of direct cytotoxic effects of lenalidomide on the del(5q) clone [31]. In both MDS-003 and MDS-004, grade 3/4 hematologic AEs occurred primarily during the first two treatment cycles and decreased thereafter (data for MDS-004 shown in Figure 1) [17, 32, 33]. Hematologic AEs were generally managed with dose modifications, interruptions, or growth factor support.

Table 4.

Most common (≥5% of patients in any group) grade 3/4 adverse events reported in MDS-003 (overall) and MDS-004 (drug-related)

| Overall AEs in the MDS-003 study [17], n (%) | Drug-related AEs in the MDS-004 study [18]a, n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mgb (N = 148) | LEN 10 mgc (N = 69) | LEN 5 mgd (N = 69) | Placebod (N = 67) | |

| Neutropenia | 81 (55) | 52 (75) | 51 (74) | 10 (15) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 65 (44) | 28 (41) | 23 (33) | 1 (1) |

| Leukopenia | 9 (6) | 6 (9) | 9 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 10 (7) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 4 (3) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Rash | 9 (6) | NA | NA | NA |

Only overall AEs have been reported for MDS-003 and only drug-related AEs have been reported for MDS-004.

aSafety population, double-blind phase.

bThe first 46 patients were treated on days 1–21 of 28-day cycles, and following a protocol amendment, 102 patients received continuous daily dosing [17].

cDays 1–21 of 28-day cycles.

dContinuous daily dosing.

AE, adverse event; LEN, lenalidomide; NA, not available.

Figure 1.

Grade 3/4 neutropenia (A) and thrombocytopenia (B) associated with lenalidomide (LEN) treatment by cycle in MDS-004 [32, 33].

In terms of long-term safety, lenalidomide has been associated with hypothyroidism. In a retrospective study of patients treated with lenalidomide (N = 170), 6% developed thyroid abnormalities attributed to lenalidomide [34]. Symptoms of thyroid dysfunction overlap with common side-effects of lenalidomide, and thyroid hormone levels are typically not regularly evaluated in patients treated with lenalidomide. However, they should be, as symptoms of thyroid dysfunction could be alleviated with appropriate treatment. In a retrospective study of patients with MDS (N = 1248, predominantly non-del[5q]) at the Moffitt Cancer Center, including 210 patients treated with lenalidomide, second primary malignancies (SPM) were not associated with lenalidomide treatment [35]. Of the 41 SPM observed, 5 (2.4%) were in patients treated with lenalidomide and 36 (3.5%) were in patients treated without lenalidomide.

short- and long-term health-related quality-of-life outcomes

Anemia, the most common cytopenia in MDS, can be accompanied by symptoms including fatigue that can negatively impact patient quality of life [7, 8]. The phase 3 MDS-004 study examined the impact of lenalidomide treatment compared with placebo on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale [36]. The FACT-An is a patient self-administered questionnaire specifically designed to measure the effect of therapy on anemia-related symptoms with a large focus on fatigue [37]. At week 12, changes in HRQOL from baseline with lenalidomide were significantly greater than with placebo [36]. Continued HRQOL improvements were observed throughout the course of lenalidomide treatment, as late as week 48, the latest time point for which assessments were reported. Patients who achieved RBC-TI with lenalidomide treatment, as well as those with hemoglobin responses, had significantly greater changes in HRQOL from baseline compared with nonresponders. Clinically meaningful HRQOL improvements were additionally observed in patients who crossed over from placebo to lenalidomide treatment following study unblinding at week 16. Similarly, in a phase 2, single-arm, Italian study, lenalidomide treatment also significantly improved HRQOL in several domains of the MDS-specific QOL-E questionnaire [38]. Considering the impact on clinical as well as quality-of-life outcomes, lenalidomide has potential to improve the well-being of patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS [36].

The quality-of-life burden of transfusion dependence versus independence was factored into an analysis of cost effectiveness of lenalidomide treatment modeled on data from the MDS-003 study [39]. This study found that costs of lenalidomide treatment were largely outweighed by reductions in transfusions and recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO) use. Overall, the model supported the cost effectiveness of lenalidomide therapy compared with best supportive care (including EPO) when accounting for potential increases in quality of life.

practical recommendations for lenalidomide treatment in patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS

For patients with RBC-TD lower-risk, del(5q) MDS, lenalidomide treatment offers important short- and long-term clinical benefits, including high rates of durable RBC-TI, high rates of CyR associated with durable RBC-TI, OS benefits, response-driven reduced risk for AML progression, and HRQOL benefits [17, 18, 20–22, 36]. For these reasons, in our practice, we generally use lenalidomide as the first-line treatment of RBC-TD patients with lower-risk, del(5q) MDS. For patients who are not RBC-TD, and who have a serum EPO level of <500 mU/ml, we may first offer a trial of a erythropoiesis-stimulating agent before the initiation of lenalidomide treatment.

Although lower-risk MDS patients may have a more indolent disease course than those with higher-risk disease, practitioners may consider screening patients for TP53 gene mutations before determining treatment course, given the inferior outcomes with lenalidomide treatment [26, 27, 29, 30]. Currently, there are no clear guidelines on how to manage these patients. It is not known if their outcomes are improved by treatment with hypomethylating agents or transplant. In our practice, we treat these patients with lenalidomide under close observation. We also encourage identifying clinical trials for treating this patient population with unmet needs.

The evidence supporting the clinical benefits of lenalidomide treatment highlights the importance of optimizing treatment dose and duration to enhance outcomes. Results of the MDS-004 study show that a 10-mg starting dose of lenalidomide yields higher rates of CyR versus a 5-mg dose, and that a greater cumulative dose of lenalidomide administered during treatment cycle 1 was associated with improved AML-free survival [21]. Thus, to achieve optimal outcomes with lenalidomide treatment, dose and early treatment intensity are crucial. A 10-mg starting dose should be employed in the absence of limiting renal function with planned dose interruption or reduction for treatment-related cytopenias, which have been shown to correlate with response [31].

Although many patients begin to respond in cycle 1, onset of RBC-TI with lenalidomide treatment may take up to four treatment cycles [18] and, for this reason, response to lenalidomide should be assessed after 2–4 months of treatment [13]. The relationship between the short-term benefits of lenalidomide treatment (durable RBC-TI and CyR) and the long-term overall and AML-free survival benefits [18, 20, 21] supports maximizing lenalidomide treatment duration, even after a response is observed. Therefore, lenalidomide-associated AEs (e.g. myelosuppression) should be optimally managed with treatment interruption and dose reduction, with discontinuation of treatment only when appropriate.

funding

Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Celgene Corporation.

disclosure

RSK has received grant funding, honoraria, and travel support from Celgene Corporation. He has participated as an advisor for Celgene Corporation. RSK has received grant funding and speaker fees from, and participated as a consultant for Incyte. AFL has received grant funding from Celgene Corporation. He has acted as a consultant and provided expert testimony for Celgene Corporation.

acknowledgements

The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article, but thank Stacey Rose, PhD, and Jennifer Leslie, PhD, of MediTech Media, for providing medical editorial assistance.

references

- 1.Cazzola M, Malcovati L. Myelodysplastic syndromes—coping with ineffective hematopoiesis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaney ML, Golde DW. Myelodysplasia. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann WK, Lubbert M, Hoelzer D, Phillip Koeffler H. Myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematol J 2004; 5: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malcovati L, Della Porta MG, Strupp C et al. Impact of the degree of anemia on the outcome of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and its integration into the WHO classification-based Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS). Haematologica 2011; 96: 1433–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Ravandi F et al. Proposal for a new risk model in myelodysplastic syndrome that accounts for events not considered in the original International Prognostic Scoring System. Cancer 2008; 113: 1351–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2012; 120: 2454–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Malcovati L. Supportive care, growth factors, and new therapies in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Rev 2008; 22: 75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen AJ, Essink-Bot ML, Beckers EA et al. Quality of life measurement in patients with transfusion-dependent myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol 2003; 121: 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 2009; 114: 937–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giagounidis AA, Germing U, Aul C. Biological and prognostic significance of chromosome 5q deletions in myeloid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haase D, Germing U, Schanz J et al. New insights into the prognostic impact of the karyotype in MDS and correlation with subtypes: evidence from a core dataset of 2124 patients. Blood 2007; 110: 4385–4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sole F, Espinet B, Sanz GF et al. Incidence, characterization and prognostic significance of chromosomal abnormalities in 640 patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes. Grupo Cooperativo Espanol de Citogenetica Hematologica. Br J Haematol 2000; 108: 346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCCN Clinical Guidelines in Oncology. Myelodysplastic Syndromes. V.1.2016 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mds.pdf.

- 14.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 1997; 89: 2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revlimid (Lenalidomide) [Package Insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revlimid (Lenalidomide) [Summary of Product Characteristics]. Uxbridge, UK: Celgene Europe Ltd; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenaux P, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D et al. A randomized phase 3 study of lenalidomide versus placebo in RBC transfusion-dependent patients with low-/intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del5q. Blood 2011; 118: 3765–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekeres MA, Swern AS, Fenaux P et al. Validation of the IPSS-R in lenalidomide-treated, lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome patients with del(5q). Blood Cancer J 2014; 4: e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.List AF, Bennett JM, Sekeres MA et al. Extended survival and reduced risk of AML progression in erythroid-responsive lenalidomide-treated patients with lower-risk del(5q) MDS. Leukemia 2014; 28: 1033–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekeres MA, Swern AS, Giagounidis A et al. Association of cytogenetic response with RBC transfusion-independence and AML-free survival in lenalidomide-treated patients with IPSS low-/Int-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q). In Presented at the 55th Annual Meeting and Exposition of the American Society of Hematology, 5–8 December 2013, New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuendgen A, Lauseker M, List AF et al. Lenalidomide does not increase AML progression risk in RBC transfusion-dependent patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk MDS with del(5q): a comparative analysis. Leukemia 2013; 27: 1072–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kantarjian H et al. Report of an international working group to standardize response criteria for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2000; 96: 3671–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tehranchi R, Woll PS, Anderson K et al. Persistent malignant stem cells in del(5q) myelodysplasia in remission. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1025–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komrokji RS, Padron E, Ebert BL, List AF. Deletion 5q MDS: molecular and therapeutic implications. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2013; 26: 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jädersten M, Saft L, Smith A et al. TP53 mutations in low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q) predict disease progression. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1971–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bally C, Ades L, Renneville A et al. Incidence and prognostic value of TP53 mutations in lower risk MDS with del 5q. Blood 2012; 120.(21) [abstract 2809]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2496–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei S, Chen X, McGraw K et al. Lenalidomide promotes p53 degradation by inhibiting MDM2 auto-ubiquitination in myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. Oncogene 2013; 32: 1110–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saft L, Karimi M, Ghaderi M et al. P53 protein expression independently predicts outcome in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q). Haematologica 2014; 99: 1041–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekeres MA, Maciejewski JP, Giagounidis AA et al. Relationship of treatment-related cytopenias and response to lenalidomide in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5943–5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenaux P, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D et al. Safety of lenalidomide (LEN) from a randomized phase III trial (MDS-004) in low-/int-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) with a del(5q) abnormality. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(suppl 15) [abstract 6598]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtin SE, Ridgeway JA, Fu T, Tinsley S. Management of lenalidomide-associated cytopenias in myelodysplastic syndromes: practical take-aways from clinical trials. Presented at JADPRO LIVE, 25–26 January 2014, St Petersburg, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Figaro MK, Clayton WJ, Usoh C et al. Thyroid abnormalities in patients treated with lenalidomide for hematological malignancies: results of a retrospective case review. Am J Hematol 2011; 86: 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollison DE, Shain KH, Lee J et al. Subsequent primary malignancies among myelodysplastic syndrome patients treated with or without lenalidomide. Blood 2014; 124.(21) [abstract 413].25359993 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revicki DA, Brandenburg NA, Muus P et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes of lenalidomide in transfusion-dependent patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with a chromosome 5q deletion: results from a randomized clinical trial. Leuk Res 2013; 37: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cella D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale: a new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol 1997; 34: 13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliva EN, Latagliata R, Lagana C et al. Lenalidomide in International Prognostic Scoring System low and intermediate-1 risk myelodysplastic syndromes with del(5q): an Italian phase II trial of health-related quality of life, safety and efficacy. Leuk Lymphoma 2013; 54: 2458–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goss TF, Szende A, Schaefer C et al. Cost effectiveness of lenalidomide in the treatment of transfusion-dependent myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States. Cancer Control 2006; 13(suppl): 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]