Abstract

Human cystatin C (cysC) is a soluble basic protein belonging to the cysteine protease inhibitor family. CysC is a potent inhibitor of cathepsins - proteolytic enzymes that degrade intracellular and endocytosed proteins, remodel extracellular matrix, and trigger apoptosis. Inhibition is via tight reversible binding involving the N-terminus as well as two β-hairpin loops of cysC. As a significant component of cerebrospinal fluid, cysC has numerous other functions, including support of neural stem cell growth and differentiation. Several studies suggest that cysC may bind to the Alzheimer-related protein beta-amyloid (Aβ), and inhibit its aggregation and toxicity. Because of an increasing recognition of its important biological roles, there is considerable interest in methods to produce full-length recombinant human cysC. Several researchers have reported success, but with processes that require multiple purification steps. Here we report successful production of human cysC using an intein-based expression system and a simple one-column purification scheme. The recombinant protein so obtained was natively folded and active as an enzyme inhibitor. Unexpectedly, even mild concentration by ultrafiltration caused significant oligomerization. The oligomers are noncovalent and retain the native secondary structure and inhibitory activity of the monomer. The oligomers, but not the monomers, were highly effective at inhibiting aggregation of Aβ. These results demonstrate the critical importance of careful physicochemical characterization of recombinant cysC protein prior to evaluation of its biological functions.

Keywords: cystatin C, beta-amyloid, aggregation, oligomers, amyloid, light scattering

Introduction

Human cystatin C (cysC) is a soluble basic protein belonging to the cysteine protease inhibitor family. Relatively abundant in cerebrospinal fluid, the 13.3 kDa protein (120 residues) is natively non-glycosylated and contains two disulfide bonds 1. Each monomer contains a single five-stranded β-sheet encircling a lone α-helix 2. CysC is a potent inhibitor of cathepsins, which are proteolytic enzymes that are localized primarily to the endosomal/lysosomal system. Inhibition is via tight reversible binding involving the N-terminus and two β-hairpin loops of cysC 3, 4. Cathepsins degrade intracellular and endocytosed proteins, and serve a role in remodeling and degrading extracellular matrix. Leakage of cathepsin B (catB) to the cytosol leads to caspase activation and apoptosis 5, 6. Additionally, cathepsins are involved in adaptive immunity and angiogenesis, and a high level of cathepsin activity has been linked to neurological and cardiovascular disorders, and to tumor metastasis 6, so cysC serves as a regulatory component in these processes. Since cysC is predominantly in circulating fluids while cathepsins are predominantly intracellular, cysC protects against widespread tissue damage due to proteolyis by leaked cathepsins. Besides its well-known cathepsin inhibitory activity, cysC inhibits mammalian legumain, an enzyme involved with antigen processing 7. CysC also plays a role in neural stem cell growth and glial development 8, 9. Wildtype cysC is a component in the amyloid deposits found in patients with spontaneous cerebral amyloid angiopathy 10. A single mutation (L68Q) renders cysC more prone to aggregate into amyloid fibrils and causes a hereditary cerebral amyloidosis leading to lethal hemorrhages 11, 12 .

Several studies provide a specific link between cysC and the Alzheimer-related protein, beta-amyloid (Aβ) 13. Aggregation of Aβ into amyloid fibrils and deposition in extracellular senile plaques is one of the defining characteristics of Alzheimer's disease (AD). CysC and Aβ were found co-deposited in senile plaques of AD patients 14, and soluble cysC-Aβ complexes were detected in cerebrospinal fluid from AD patients 15. CysC bound to Aβ and inhibited Aβ fibril formation in vitro 16, reduced in vitro formation of soluble Aβ oligomers and protofibrils, and increased non-fibrillar insoluble aggregates 17. Overexpression of cysC in transgenic APP mice led to a reduction in amyloid plaque deposition in vivo 18, 19. CysC partially protected neuroblastoma cells and primary cultured neurons from Aβ toxicity, although the protection was believed to be direct rather than via any effect on Aβ aggregation 20. Besides the direct interaction between cysC and Aβ, the protease inhibitory activity of cysC may play a role in AD. CysC expression in AD neurons is elevated, and the inhibitor is colocalized with catB 21. CatB degrades Aβ into non-fibril-forming fragments, and this degradation is inhibited by cysC 22, 23.

Given the protein's important biological roles, several different strategies have been employed to produce full-length recombinant human cysC. Grubb and coworkers 24, 25 were the first to report production in E. coli. CysC was secreted into the bacterial periplasm and isolated using ion exchange chromatograpy followed by size exclusion chromatography. In an attempt to improve yield, Hayashi et al. 26 used the peptide tag 4AaCter and codon optimization. Inclusion bodies containing the fusion protein were solubilized in urea, and the denatured protein was affinity purified on a metal affinity column. Following elution, the protein was refolded using a two-step dialysis scheme, then the peptide tag was cleaved by addition of a specific protease and the target protein was purified by ion exchange. Yield was approximately 7 mg purified protein per liter culture. Zhang et al. 27 took a different approach, producing the protein as a fusion product with maltose-binding protein to enhance solubility plus a His6 tag to allow for affinity purification. The soluble fusion product was purified by nickel chromatography, then reacted with protease to remove the His tag and maltose-binding protein, and re-purified on a nickel column, with the detagged protein recovered in the flowthrough. About 20 mg fusion protein was obtained per L culture, with a final yield of about 9 mg/L. Very recently, Zhou et al. 28 expressed cysC as a fusion protein with PelB, a self-cleaving signal sequence which directs the protein into the E. coli periplasm for disulfide-stabilized folding. Protein was purified from cell lysate by cation exchange followed by size exclusion chromatography, for a reported yield of 20 mg cysC per L culture. Alternatively, production of cysC in Pichia pastoris yeast-based expression system has been reported 29, 30, but this approach is less convenient than E. coli.

Here we report successful production of human cysC in E. coli using an intein-based expression system and a simple one-column purification scheme. The denatured fusion protein is captured by a chitin affinity column and refolded on-column. The folded protein is cleaved from the intein tag by a change in buffer pH and temperature, and easily eluted from the column. The recombinant protein so obtained was natively folded and active as an enzyme inhibitor. Unexpectedly, we found that mild concentration by ultrafiltration caused significant oligomerization. We report preliminary characterization of these cysC oligomers and their interaction with Aβ. Our results demonstrate the critical importance of careful physicochemical characterization of the cystatin C protein.

Materials and Methods

Cystatin C production and purification

The human cystatin C gene was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli using Genscript's OptimumGene algorithm (Supplementary Figure S1). The gene was synthesized with NruI and BamHI restriction sites at 5′ and 3′ positions, respectively, and ligated into the pTWIN1 plasmid (New England Biolabs). BL21-DE3 cells (New England Biolabs) were transformed with ligated plasmid and cultured in 500 mL of LB media containing 100 mg/L ampicillin. Protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG during mid log-phase growth. After 3 hours at 37 °C, the bacteria were harvested, pelleted, and re-suspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, pH 9.0, containing 8 M urea). Cells were lysed by sonication for 15 minutes in an ice bath. Excess cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation and crude lysate was applied to a chitin affinity column (New England Biolabs) equilibrated to 4 °C (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 9.0, containing 4 M urea). The column was thoroughly washed with buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0), to remove unbound material and to allow on-column refolding of bound protein. The column was equilibrated with elution buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 6.5), then incubated at room temperature overnight to initiate cleavage. CysC was eluted from the column, dialyzed into PBSA (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% wt/vol NaN3, pH 7.4) overnight, and stored at 4 °C. The mass spectrum was recorded by LC/MSD TOF (Agilent), using electrospray ionization.

20 μl each of cell lysate, chitin column flowthrough, and final cysC elution were mixed with 10X concentrated solutions of DTT and SDS (final concentration of 2% wt/vol SDS, 1 mM DTT) and boiled for 5 minutes. For non-boiled and non-reduced samples, SDS only was added to a final concentration of 2%. 12 μl of each sample was loaded onto a 4-20% gradient Bis-Tris gel (Thermo) and electrophoresed for 45 minutes at constant 125 V. The gel was stained with Coomassie buffer (0.1% wt/vol Coomassie brilliant blue R-250, 50% vol/vol methanol, 10% vol/vol glacial acetic acid) and destained overnight in destaining solution (50% vol/vol methanol, 10% vol/vol glacial acetic acid).

Centrifugal ultrafiltration

CysC as eluted from the chitin column was typically dilute (∼ 0.2 mg/ml). The protein was concentrated via ultrafiltration at 4°C with a 3 kDa MWCO regenerated cellulose membrane (Amicon-15, EMD Millipore) in a swinging-bucket rotor operated at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo), using a molar extinction coefficient of 11,100 AU cm-1 M-1 31. CysC was typically concentrated up to 1 mg/ml using this method.

In some experiments, concentrated cysC was ultrafiltered in a 30 kDa MWCO regenerated cellulose membrane filter device (Amicon-15, EMD Millipore). Centrifugal filtration devices were operated at 4,000 rpm for approximately 15 minutes at 4 °C. Both filtrate and retentate were collected.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

CysC (1 mg/ml) was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (Merck Millex HV) directly into a scrupulously cleaned quartz cuvette. The cuvette was inserted into a BI-200SM goniometer (Brookhaven) with detector positioned at 90° and viewing aperture opened to 400 μm diameter. The cuvette temperature was maintained at 37 °C. Fluctuations in scattering intensity from a 150 mW, 488 nm laser source (Innova 90C-5, Coherent) were used to build the homodyne autocorrelation function (TurboCorr with 9KDLSW software, Brookhaven). Data were analyzed using the method of cumulants, to calculate a z-average hydrodynamic diameter, and the CONTIN NNLS algorithm, to determine the particle size distribution. The total scattered intensity at 90° was also measured; scattering from buffer was measured and subtracted from the sample scattered intensity.

Glutaraldehyde crosslinking

CysC was diluted to 20 μM with PBSA. Glutaraldehyde stock solution (50% vol/vol, Sigma) was diluted in half with PBSA, then mixed with 50 μl protein to a final concentration of 1% glutaraldehyde and incubated at room temperature for 1 minute. The crosslinking reaction was quenched by addition of NaBH4 (7% wt/vol, Sigma) to a final concentration of 0.28%. SDS and DTT were added to the samples (final concentration 2% wt/vol SDS, 1 mM DTT), and the samples were boiled for 5 minutes before loading onto a 4-20% Bis-Tris gradient gel (Thermo). Electrophoresis was performed for 40 minutes at constant 125 V. Gels were fixed and stained using a silver stain kit (Pierce).

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CysC (20 μM) was extensively dialyzed into fluoride-containing buffer (10 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaF, pH 7.4). CD spectra of monomers and oligomers were measured on an Aviv model 420 CD spectrometer between 190 – 250 nm. Measurements from filtered fluoride buffer were subtracted from the protein samples. CD spectra were analyzed using the CONTINLL algorithm [Sreerama, 2000], using SP43 as the basis set.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Samples were diluted to 10 μM with PBS A, fixed on a pioloform-coated grid, and stained with methylamine tungstate. Images were taken by with a Philips CM120 scanning transmission electron microscope (FEI Corp.).

Enzymatic activity assays

Enzyme inhibitory activity was evaluated against papain and catB. Lyophilized papain (Sigma) was reconstituted to 2 mg/ml in Tris assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 0.02% Tween 20 to prevent nonspecific protein adsorption 32. Papain was activated by addition of 5 mM DTT and room temperature incubation for 15 minutes. Cathepsin B (0.437 mg/ml, Enzo) was diluted to 3.4 μM into MES assay buffer (25 mM MES, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% Tween 20, pH 6.0) and activated by addition of 5 mM DTT 33.

CysC (15 μM) was diluted into Tris (papain assay) or MES (cathepsin B assay) buffer to 40-800 nM and mixed with activated papain (400 nM) or cathepsin B (200 nM) in equal volume. Mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes, then diluted ten-fold in either Tris (papain) or MES (cathepsin B) assay buffer. Freshly-prepared fluorogenic substrate, Z-FR-AMC (R&D Systems, 200 μM in Tris or MES assay buffer) was added in equal volume to protein samples in a black polystyrene 96-well plate. The final concentrations of papain and cathepsin B were nominally 10 nM and 5 nM, respectively. CysC concentrations ranged from 0 – 20 nM. Fluorescence measurements were taken continuously in an FL800 plate reader (Biotek) for 5 minutes, using excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 460 nm, respectively. Initial reaction rates ν were calculated by linear regression of fluorescence rate of increase and normalized to V0, the reaction rate in the absence of inhibitor. Samples were prepared in duplicate in each assay. Reported data is the average over 3 (papain) or 4 (cathepsin B) independent assays.

The apparent inhibition constant, Ki,app, and the total concentration of active enzyme, [E], were determined by least-squares fitting of ν/V0 versus the total cysC concentration [I] to the Morrison equation for tight-binding competitive enzyme inhibition (eq. 1) 34, 35:

| (1) |

The true inhibition constant Ki was determined from Ki,app and the substrate concentration [S] by:

| (2) |

Km was measured by titration of Z-FR-AMC against 5 nM enzyme. Briefly, substrate was prepared at concentrations between 0 and 100 μM in either Tris assay buffer (papain) or MES assay buffer (cathepsin B). Activated enzyme was added, and initial reaction rates were determined by continuous fluorescence measurements as previously described. Plots of substrate concentration versus initial reaction rate were fit to the Michaelis-Menton rate expression, with Km and Vo,max as fitting parameters.

Aβ interaction studies

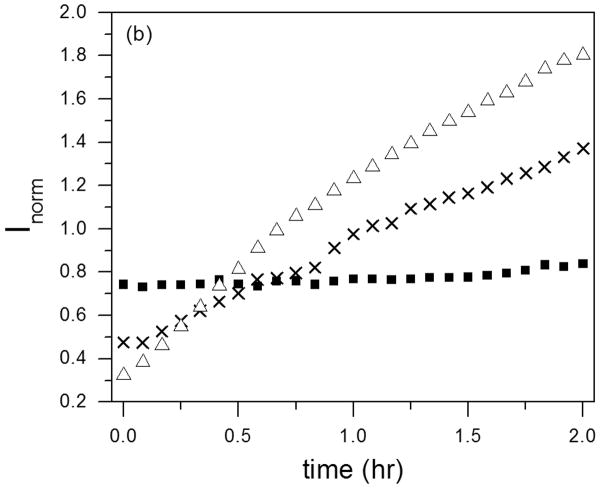

Lyophilized Aβ(1-40) (AnaSpec, San Jose, California) was reconstituted to 2.8 mM in denaturing buffer (100 mM glycine, 8 M urea, pH 10, filtered through 0.22 μm Millex PVDF syringe filter) to fully disaggregate the peptide 36. Refolding and aggregation of Aβ was initiated by rapid dilution to 28 μM in PBSA (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% wt/vol NaN3, pH 7.4, filtered through 0.22 μm Millex PVDF syringe filter). Alternatively, Aβ was rapidly diluted to 28 μM in PBSA containing either cysC monomers or oligomers. The final concentration of cysC was 14 μM (monomer basis). Each sample was filtered (0.22 μm Millex PVDF) directly into a clean cuvette immediately prior analysis by DLS. Sample temperatures were held constant at 37 °C. Aβ aggregate growth in all samples was monitored for 2 hours using 5-minute autocorrelation averaging periods. The normalized scattering intensity was calculated by subtracting the buffer scattering from the sample scattering intensity and then dividing by the total protein concentration in each sample.

ANS fluorescence

CysC was mixed with ANS (final concentrations of 1 μM protein, 28 μM ANS in PBSA) and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Samples were excited at 370 nm and emission spectra were recorded for 440 – 500 nm (QuantaMaster 40, PTI). The emission spectrum of PBSA was recorded and subtracted from each sample using FelixGX software.

Results

Cystatin C production and purification

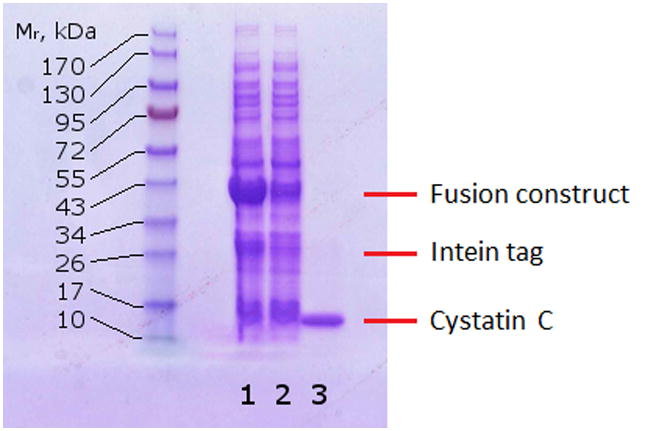

Expression of cystatin C in the pTWIN1 plasmid produces a fusion protein that, at high pH and 4°C, binds to a chitin affinity column. Denaturation with urea was necessary in order for the fusion protein to bind to the chitin column. After adsorption, washing with cold buffer at pH 9 removed the urea, allowing on-column refolding. At low pH and room temperature, the intein tag undergoes C-terminal peptide bond cleavage, releasing full-length cysC (Supplementary Figure S2). Figure 1 shows SDS-PAGE analysis of cell lysate, column flowthrough, and eluted cysC. The fusion protein is at high concentration in the cell lysate, along with some cysC and intein tag (30 kDa) due to premature cleavage. Most of the fusion protein is captured by the chitin affinity column, whereas the untagged cysC is in the flowthrough. Highly purified cysC is obtained upon elution. In a typical 500 mL batch fermentation, 25 mL of 0.2 – 0.3 mg/mL cysC was collected in the chitin column elution, for a yield of 10-15 mg pure protein per L of culture.

Figure 1.

Reducing SDS-PAGE of cell lysate (lane 1), chitin column flow-through (lane 2), and chitin column elution after washing and flushing with elution buffer at room temperature (lane 3).

Purified protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry (Supplemental Figure S3). The expected molecular mass (13,343 Da) is the predominant component of the sample. Small peaks of singly oxidized (13,359 Da) and doubly oxidized (13,374 Da) cysC were present. These are likely due to methionine oxidation 37, which also occurs in vivo, possibly accumulating during the aging process 38. No other peak was detected, demonstrating that cysC was not truncated or degraded during purification and storage.

Discovery of cystatin C oligomers

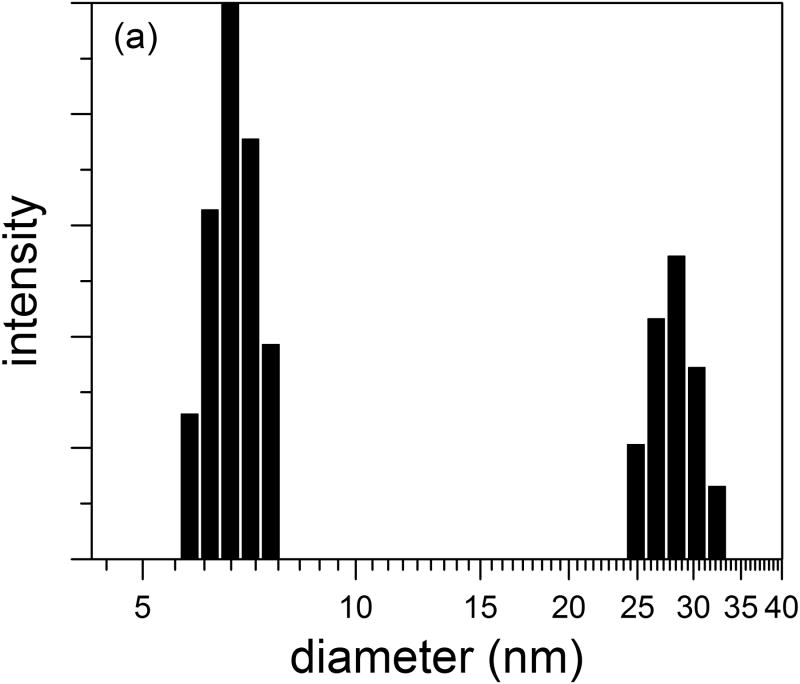

Purified cysC was concentrated to 1 mg/ml by ultrafiltration in a 3 kDa MWCO centrifuge filter, and protein hydrodynamic diameter was measured by DLS. Based on a spherical geometry and a specific volume of 1.1 mL/g for hydrated protein, we calculated an expected hydrodynamic diameter of 3.6 nm for cysC monomers, a number that is consistent with pulse-field gradient NMR measurements 39. For our sample (representative chosen from 5 replicates), the z-average hydrodynamic diameter was 9.9 nm (polydispersity of 0.22). Further analysis of the autocorrelation function to obtain an intensity-weighted particle size distribution revealed a bimodal distribution, with a major peak centered at 7 nm and a minor peak centered around 28 nm (Figure 2a). These data indicate that concentrated solutions of cysC contain small oligomers (dimers, 4.5 nm diameter, to ∼12-mers, 8 nm diameter, assuming solid spheres) as well as a small population of larger aggregates. The intensity distribution is weighted according to the scattering intensity, and is the most natural representation of the data. The mass-weighted distribution (Figure 2b) is a transformation of the intensity distribution, assuming particles are hard spheres of constant density. This representation shows that nearly all of the mass is present as small oligomers.

Figure 2.

Size distribution of purified cystatin C. Hydrodynamic diameter distribution was determined by CONTIN analysis of autocorrelation functions. (a) Intensity- and (b) mass-weighted distributions.

The stability of the oligomers was investigated by diluting the sample and measuring its light scattering intensity. Since scattering intensity is a linear function of mass concentration and a sixth-order function of particle size, any dissociation of aggregates should sharply reduce the total scattering intensity of the sample. The observed relationship between dilution and scattering intensity was linear (data not shown), indicating that the aggregates did not dissociate within a two-day time period.

Separation of monomeric cysC from oligomers

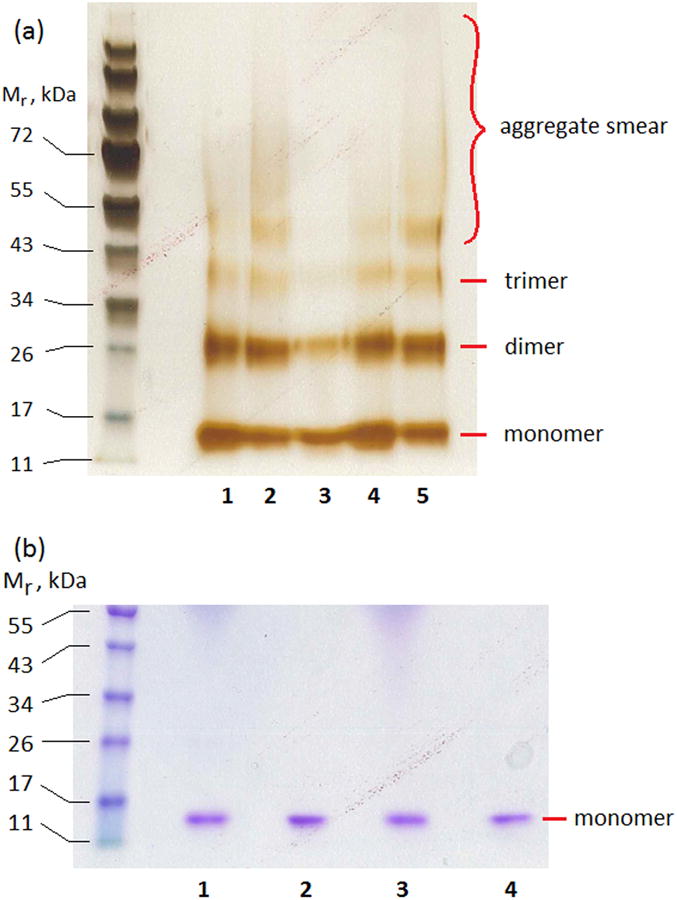

To further establish the existence of oligomers, we crosslinked protein solutions using glutaraldehyde. (In preliminary experiments, the crosslinking time was optimized to capture stable oligomers while minimizing unwanted crosslinking of dimers arising from random collisions, data not shown.) As eluted from the chitin column, cysC contains approximately equal-density bands of monomer and dimer, as well as a weak trimer band (Figure 3a, lane 1). After concentration by ultrafiltration in a 3 kDa MWCO membrane, some larger oligomers appear as a high-molecular-weight ‘smear’ (lane 2). To separate monomer from oligomers, the concentrated cysC was filtered through a nominal 30 kDa MWCO centrifuge filter. (Size exclusion chromatography was not used for fractionation, because of the dilution that occurs.) The filtrate and retentate were collected, adjusted to the same concentration, reacted with glutaraldehyde to crosslink any multimers, then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After size fractionation through a 30 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration membrane, the filtrate is predominantly monomer, with some dimer (lane 3). The dimer (27 kDa) could partially permeate through the nominal 30 kDa filter; in addition, some collision-induced crosslinking is possible. The filtrate (monomer) was re-concentrated by 3 kDa ultrafiltration, after which aggregates re-appeared (lane 4). The retentate contained some monomer but also a high fraction of dimers and larger multimers (lane 5). In the absence of crosslinking, all samples ran as pure monomers, either in the absence or presence of DTT and boiling (Figure 3b). This result indicates that the multimers are SDS-soluble and noncovalent, and are not formed by incorrect disulfide bond formation.

Figure 3.

(a) SDS-PAGE of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked cysC, showing purification of monomers from oligomers. Lane 1: Chitin column elution. Lane 2: Concentration by 3 kDa ultrafiltration. Lane 3: Filtrate of 30 kDa ultrafiltration. Lane 4: Concentration of filtrate of lane 3 by 3 kDa ultrafiltration. Lane 5: Retentate of 30 kDa ultrafiltration. Each lane contains 2.5 μg total protein. (b) Comparison of reducing and non-reducing conditions. Lane 1: Filtrate (monomer-rich) fraction, reduced and boiled. Lane 2: Filtrate (monomer-rich) fraction, non-reduced, not boiled. Lane 3: Retentate (oligomer-rich) fraction, reduced and boiled. Lane 4: Retentate (oligomer-rich) fraction, non-reduced and not boiled. Each lane contains 3 μg total protein.

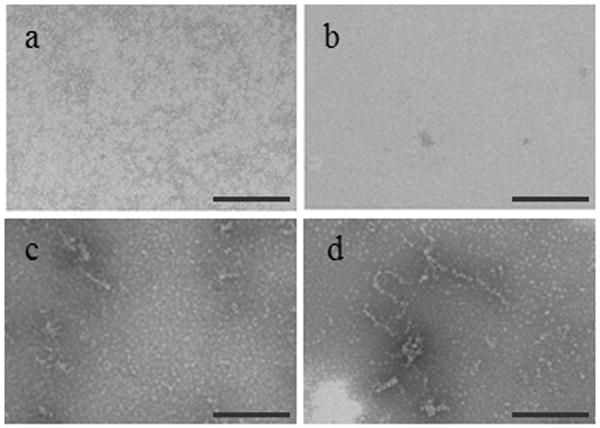

To further demonstrate that oligomers form during the concentration process, monomeric cysC (8 μM) was ultrafiltered to varying degrees of concentration. Samples were taken at low (1.12-fold), moderate (2-fold), and high (5.6-fold) concentration ratios. Each sample was diluted back to 8 μM, then fixed, stained, and imaged by TEM (Figure 4). In the monomeric starting material or at the 1.12-fold concentration ratio, no aggregates were apparent (Figure 4a,b). Small globular clusters began to appear at 16 μM (Figure 4c). At the highest concentration ratio (Figure 4d), small globular clusters and larger ‘wormlike’ aggregates were observed. The small globular clusters are ∼5-10 nm in diameter, consistent with light scattering observations (Figure 2). The larger aggregates could belong to the ∼30 nm population seen by DLS.

Figure 4.

TEM images of purified monomeric cysC after various stages of concentration via ultrafiltration using a 3 kDa MWCO membrane. Monomeric cysC, initially at 8 μM (a) was ultrafiltered to the following final concentrations: 9 μM (b), 16 μM (c), and 45 μM (d). Each sample was diluted back to 8 μM prior to TEM imaging. Each scale bar is 200 nm.

Characterization of cysC monomer and oligomers

We next compared the physicochemical properties of fractionated monomer and oligomer solutions. 10 mL cysC (15 μM) was concentrated to 1 mL via ultrafiltration in a 3 kDa filter. 4 mL PBSA was added to the concentrated protein, then the sample was centrifuged through a 30 kDa filter. 4.5 mL (primarily) monomeric cysC (22 μM) was collected in the filtrate, while 0.5 mL of oligomer-containing cysC (70 μM) was collected in the retentate. Thus, about 67% of the mixture was recovered as a monomer-rich fraction, 23% as an oligomer-rich fraction, and 10% was lost during handling.

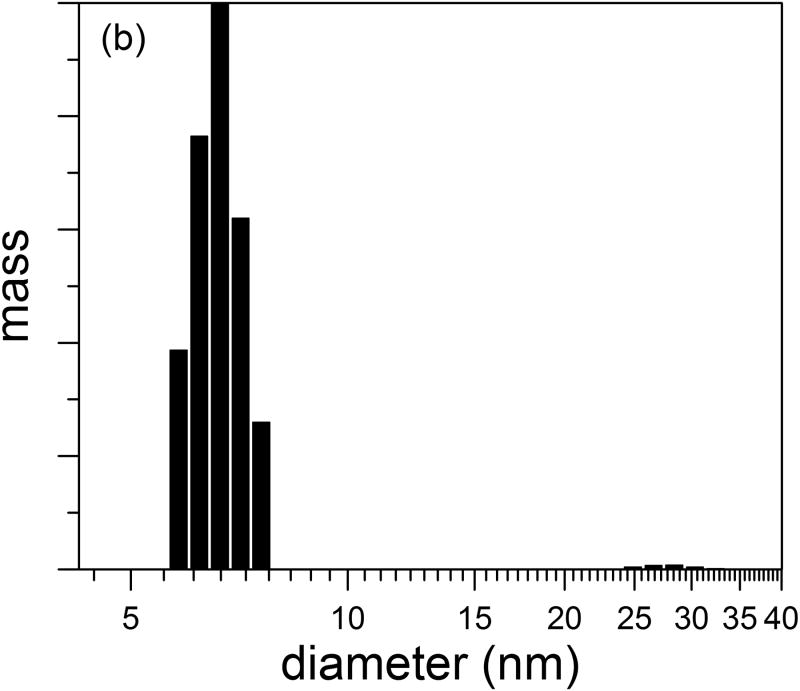

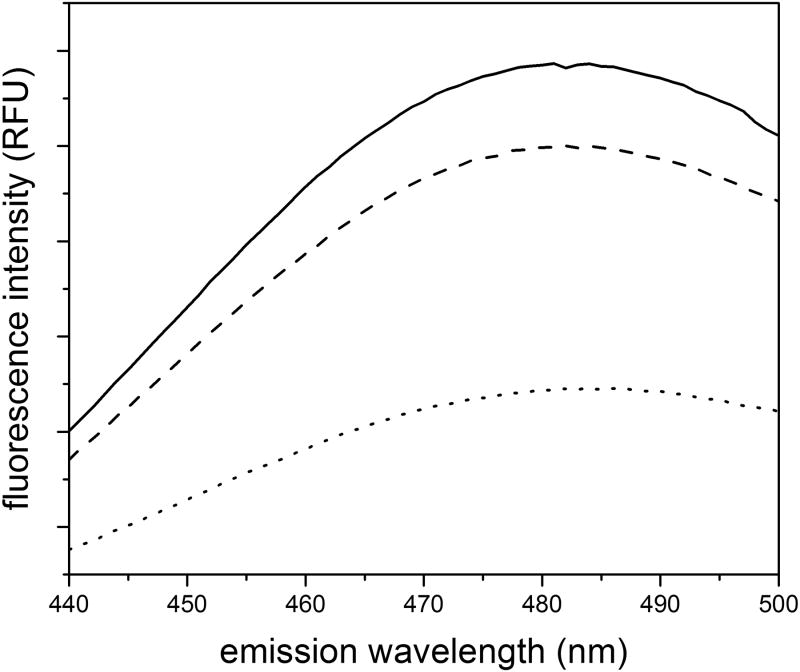

CD spectra were virtually identical for the monomer and oligomer fractions (Figure 5, Table 1). The secondary structure determination was consistent with that obtained by NMR, crystallography, and FT-IR 2, 39, 40, demonstrating that both monomer and oligomer fractions attain native secondary structure. Trp fluorescence emission spectra were similar for the monomeric and oligomeric fractions, with peak fluorescence intensity at 345 nm (data not shown), indicating that the environment around the lone tryptophan does not change, consistent with retention of native tertiary structure.

Figure 5.

CD spectra of monomeric cysC (solid line) and the fraction containing oligomers (dashed line).

Table 1. Secondary structure elements (%) of cystatin C determined by analysis of CD spectra.

| α-Helix | β-Sheet | Turn | Disorder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| monomer | 15 | 31 | 21 | 34 |

| oligomer | 11 | 33 | 22 | 34 |

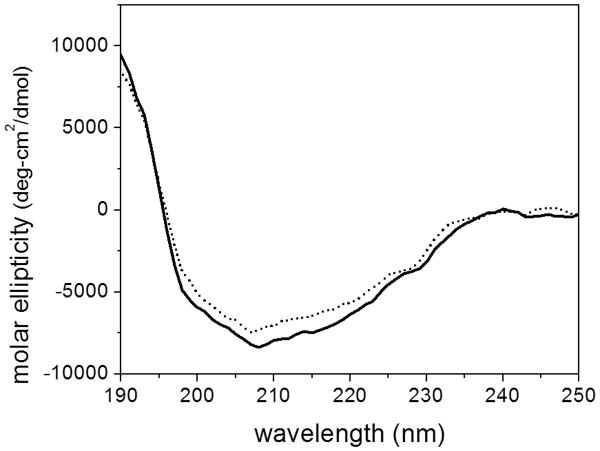

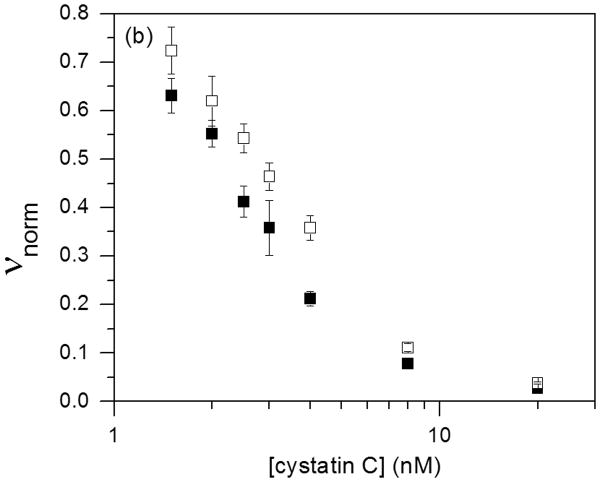

Natively folded cysC contains a pair of loops characteristic of the cystatin superfamily. These two loops, along with the flexible N-terminal domain, dock into substrate binding grooves of the cysteine protease and inhibit enzyme activity 41. Inhibition is from tight binding at a 1:1 stoichiometry. Inhibitor activity is lost in incorrectly folded cysC, including domain-swapped dimers 42. Monomer and oligomer inhibitory activity against papain and human catB were determined as a function of cysC concentration (Figure 6). The data were fit to Eq. 1 to determine Ki (Table 2). The very tight binding we observed for papain is consistent with previously reported kinetic measurements 31 and should be taken as a limiting (maximum) value. With catB, Ki for cysC monomers and oligomers are not statistically different (p < 0.05, n = 4) and are consistent with literature values (80 – 260 pM) 3, 27, 33, 43. The modest apparent decrease in inhibitory activity for the oligomer-rich fraction could be due to the reduction in effective concentration due to oligomerization.

Figure 6.

Purified cysC monomer (■) and oligomers (□) were tested for biological activity against 10 nM papain (a) and 5 nM cathepsin B (b). The cysC concentration is given as equivalent monomer. Error bars represent standard deviation of 4 replicates.

Table 2.

Cystatin C inhibition equilibrium constants from enzymatic assays. Values given are mean ± standard error.

| Enzyme | Km (μM) | CysC fraction | Ki (pM) |

| Papain | 110 ± 10 | monomer | < 5 ± 4 |

| oligomer | < 7 ± 5 | ||

| Cathepsin B | 22 ± 3 | monomer | 60 ± 20 |

| oligomer | 100 ± 30 |

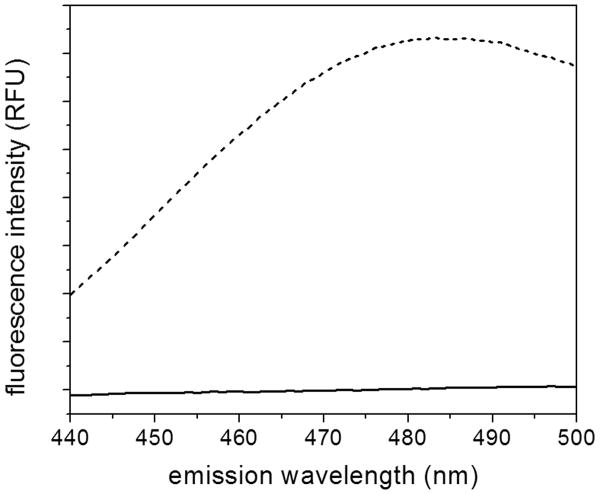

Given no differences in secondary or tertiary structure, or in biological activity, we tested for any difference in the surface properties by measuring the fluorescence of ANS. ANS binds to hydrophobic patches or cavities in proteins; binding greatly increases the fluorescence intensity 44. Here we observed a significant difference: Monomeric cysC did not affect ANS fluorescence, whereas the oligomeric protein caused a large increase in intensity (Figure 7). This suggests that the oligomerization of cysC leads to coordination of hydrophobic residues into patches or cavities to which ANS may bind.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence spectra of ANS incubated with purified monomeric (solid line) or oligomer-rich (dashed line) cysC. Excitation wavelength was 370 nm.

Oligomer formation during purification

Our data show that cysC oligomers will form from purified monomer during concentration by ultrafiltation. We next asked whether oligomers form earlier, during purification, and, if so, at what step. We hypothesized that oligomers could form on the beads during adsorption, or during the cleavage/elution step. To test these alternatives, we examined the effect of protein concentration during adsorption and during cleavage and elution. Crude cell lysate supernatant (20 ml, in lysis buffer) was prepared as usual, combined with 20 ml of wash buffer, and then split into three batches of 10 ml each. 5 ml of packed chitin beads were assigned to each batch of lysate. The first batch of lysate was purified exactly as described earlier as a control. Briefly, the lysate was applied directly to the cold chitin beads and allowed to incubate for 1 hour before washing and equilibrating with 10 mL cold elution buffer. After an overnight incubation at room temperature, the protein was eluted by flushing 10 ml elution buffer through the column. The second batch of lysate was diluted to 40 ml (using chitin equilibration buffer to maintain constant urea concentration), reducing by 4-fold the protein concentration during adsorption. The chitin beads were transferred to a 50 ml tube and the diluted lysate was added. The tube was gently shaken at 4 °C for one hour to allow adsorption to the chitin beads. Given the lower protein concentration in the lysate, the adsorbed surface concentration on the beads should also be lower than under control conditions. The beads were transferred back to the column and allowed to settle, then 10 mL cold elution buffer was added and the column was incubated at room temperature overnight. 10 ml of eluent was collected. For the third batch of lysate, protein was adsorbed from the cell lysate as in the control, but the final elution buffer volume was increased 4-fold to 40 ml. The beads were removed from the column, transferred to a 50 ml tube, and then mildly shaken at room temperature overnight in order to facilitate transfer of the cleaved protein from the bead surface to the bulk solution. In this case, the protein concentration during cleavage and elution is one-fourth that of the control conditions.

After extensive dialysis of eluted protein into PBSA, samples were diluted to the same final protein concentration, and ANS fluorescence intensity was used to measure oligomer content (Figure 8). The decrease in concentration during cleavage and elution (third batch) had only a minor effect on the oligomer content. In contrast, dilution of the cell lysate and reduction of the adsorbed protein density significantly reduced oligomer content. These results indicate that cysC oligomers form during purification due to the locally high concentration on the beads. Along with the results from ultrafiltration experiments, these data together indicate that cysC is prone to oligomer formation during any process that concentrates the protein.

Figure 8.

ANS fluorescence of cysC produced during modified purification methods: standard method (solid line), diluted cell lysate (dotted line), and diluted elution buffer (dashed line). The data shown are an average of two independent scans. Protein concentration is 1 μM protein, with 28 μM ANS.

Effect of cysC on beta-amyloid aggregation

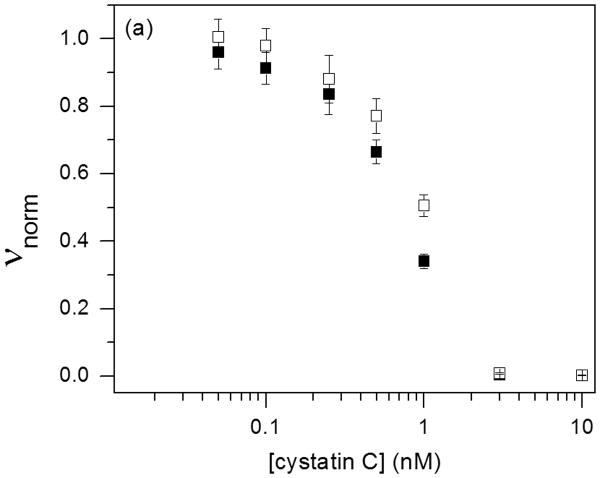

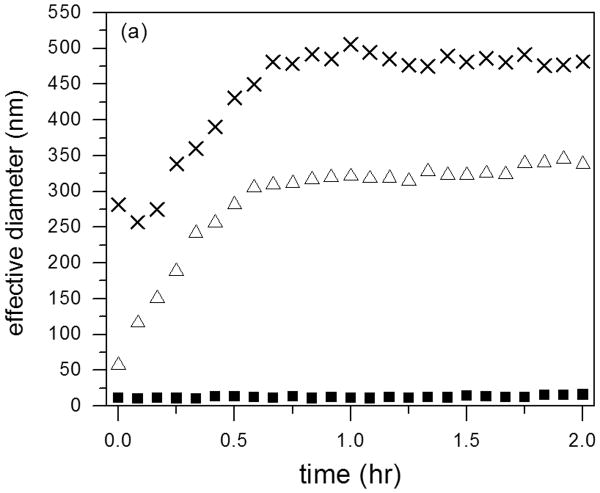

Several reports have provided evidence that cysC plays a role in preventing amyloid development during Alzheimer's disease progression 13, by binding to Aβ and inhibiting Aβ fibril formation and growth 16, 17, 45. We examined whether our cysC preparations (monomer or oligomeric) were able to slow Aβ aggregation, using DLS to measure the mean hydrodynamic diameter of aggregates. Additionally, the normalized scattering intensity, which is approximately proportional to the average molecular weight of aggregates, was measured. Scattering from cysC monomer alone (14 μM) was weak, insufficient to build an autocorrelation function. No aggregation was found over 2 hours (data not shown). For cysC oligomeric fraction (14 μM), the z-average hydrodynamic diameter was ∼12 nm, and neither the diameter nor the total scattering intensity and hydrodynamic diameter changed over 2 hours (not shown). With Aβ alone (28 μM), both the mean size and the intensity increased over the 2-h time period, indicative of the expected growth in both size and number of Aβ aggregates (Figure 9). Aβ aggregated at a similar rate in the presence of monomeric cysC; in fact, mean Aβ aggregate hydrodynamic diameter was greater in the presence of cysC. In striking contrast, oligomeric cysC completely prevented Aβ aggregation: The hydrodynamic diameter remained constant at ∼12 nm over the 2-hr observation window. Total scattering intensity was higher initially than for either Aβ alone or with monomeric cysC, was similar to oligomeric cysC alone (not shown), and did not change with time (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

Effect of cysC aggregation state on Aβ aggregation rate as measured by DLS. Effective hydrodynamic diameter (a) and normalized scattering intensity (b) were measured for Aβ alone (△), Aβ incubated with monomeric cysC (X), or Aβ incubated with oligomeric cysC ■. Aβ concentration was 28 μM. CysC concentration (monomeric or oligomer-rich) was 14 μM on a monomer basis. Representative of 3 repeats. The scattered intensity is normalized to account for the different concentrations of total protein in the samples.

Discussion

Cystatin C is a well-known member of the cysteine protease inhibitor family and also inhibits legumain, an aspargine-specific endoprotease. Increasingly, it is becoming clear that cystatin C serves myriad functions, in regulating neural stem cell differentiation, extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis 1, 5, 6, 9. It is an unusual circulating protein in that it is more concentrated in cerebrospinal fluid than in plasma, with a typical CSF concentration of 7 mg/L (about 0.5 μM) 46.

Given the biological importance of cysC, there has been renewed interest in methods of recombinant production of the protein in E. coli. Three recent papers illustrate different approaches 26-28, with reported yields of purified proteins from batch fermentation of 7-20 mg/L. In two of these methods, a fusion protein was produced, and purification required two different adsorption steps as well as an intermediate cleavage step (plus refolding, in one case) in solution. We report here successful adoption of a simpler one-step approach, in which adsorption, cleavage of the tag, and refolding all occur on a single column. Our approach resulted in good yield (10-15 mg/L) of highly pure and active cystatin C.

As one step in our purification process, we (like others) used centrifugal ultrafiltration to concentrate the protein. We observed that, above ∼20 μM, small oligomers formed. These oligomers are noncovalent and SDS-soluble, so are not detected by standard gel electrophoresis, the technique used by most researchers to show size and purity. The oligomers retain native secondary and tertiary structure. Furthermore, they inhibit papain and cathepsin B with equal activity as the separated monomers. Since by these commonly used assays the oligomers are not detectable, we suspect that other researchers may unknowingly have oligomers in their protein preparations. Grubb and coworkers have established that, at low pH, high temperature, or in the presence of chemical denaturant, cysC will form domain-swapped dimers 47. These domain-swapped dimers differ from monomers in their CD spectra, and are inactive in cysteine protease inhibition assays. Thus, the oligomers we observe are not domain-swapped, and represent a distinctly different class of cysC multimers.

CysC oligomers were formed during purification from the cell lysate, and again when purified monomers were re-concentrated by ultrafiltration. Our study of different purification schemes showed that reducing the protein concentration during adsorption also reduced cysC oligomerization. These experiments indicate that cysC oligomers may form during any step in which the protein is exposed to locally high concentrations, either due to a high adsorbed density on the chitin bead surface, or concentration polarization at the ultrafiltration membrane surface. In preliminary experiments, we concentrated cysC by slow dialysis against polyethylene glycol (3500 MWCO dialysis tubing, 100 mg/ml PEG-20 in PBSA), which removes water because of osmotic pressure. We were able to achieve 4-fold concentration (10 μM to 40 μM) without significant aggregation, presumably because the slow flux limited concentration polarization at the tubing surface.

Several groups have reported that cysC interacts with Aβ and may play a role in inhibiting Aβ fibrillogenesis and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease 13, 16-18, 20, 22. We used light scattering to probe, in solution and non-invasively, for evidence for inhibition of aggregation. We observed remarkably different behaviors of monomeric versus oligomeric cysC. Interestingly, the oligomeric cysC inhibited aggregation of Aβ, while the monomeric cysC did not. To discover a possible explanation for this, we tested the surface properties and found that cysC oligomers bind ANS strongly whereas cysC monomers do not. This suggests that the oligomerization of cysC leads to coordination of hydrophobic residues into patches or cavities to which ANS, and Aβ, may bind. Binding of Aβ to these patches or cavities of cysC oligomers would effectively sequester Aβ and prevent amyloid from forming. This finding, that interactions with Aβ depend strongly on the cysC oligomer status, has important implications for designing and interpreting experiments in which the mechanisms of cysC and Aβ interactions are probed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Successfully produced human cystatin C with a simple one-column purification scheme

Demonstrated oligomerization of cystatin C during concentration by ultrafiltration.

Showed cystatin C oligomers but not monomers arrest beta-amyloid aggregation.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation CBET-1262729. CD spectra were obtained at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biophysics Instrumentation Facility, which was established with support from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and granst BIR-9512577 (NSF) and S10 RR13790 (NIH), with technical assistance provided by Dr. Darrell McCaslin. Randall Massey provided technical assistance with TEM.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

beta-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ANS

8-Anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid

- catB

cathepsin B

- CD

circular dichroism

- cysC

cystatin C

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- MWCO

molecular weight cutoff

- PBSA

phosphate buffered saline with azide

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Z-FR-AMC

N-carbobenzyloxy-phenylalanine-arginine-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mussap M, Plebani M. Biochemistry and clinical role of human cystatin C. Crit Rev Cl Lab Sci. 2004;41:467–550. doi: 10.1080/10408360490504934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolodziejczyk R, Michalska K, Hernandez-Santoyo A, Wahlbom M, Grubb A, Jaskolski M. Crystal structure of human cystatin C stabilized against amyloid formation. Febs J. 2010;277:1726–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall A, Hakansson K, Mason RW, Grubb A, Abrahamson M. Structural Basis for the Biological Specificity of Cystatin-C - Identification of Leucine-9 in the N-Terminal Binding Region as a Selectivity-Conferring Residue in the Inhibition of Mammalian Cysteine Peptidases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5115–5121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nycander M, Estrada S, Mort JS, Abrahamson M, Bjork I. Two-step mechanism of inhibition of cathepsin B by cystatin C due to displacement of the proteinase occluding loop. Febs Lett. 1998;422:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutgens SPM, Cleutjens KBJM, Daemen MJAP, Heeneman S. Cathepsin cysteine proteases in cardiovascular disease. Faseb J. 2007;21:3029–3041. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7924com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turk V, Stoka V, Vasiljeva O, Renko M, Sun T, Turk B, Turk D. Cysteine cathepsins: From structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Bba-Proteins Proteom. 2012;1824:68–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarez-Fernandez M, Barrett AJ, Gerhartz B, Dando PM, Ni JA, Abrahamson M. Inhibition of mammalian legumain by some cystatins is due to a novel second reactive site. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19195–19203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taupin P, Ray J, Fischer WH, Suhr ST, Hakansson K, Grubb A, Gage FH. FGF-2- responsive neural stem cell proliferation requires CCg, a novel autocrine/paracrine cofactor. Neuron. 2000;28:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa A, Naruse M, Hitoshi S, Iwasaki Y, Takebayashi H, Ikenaka K. Regulation of glial development by cystatin C. J Neurochem. 2007;100:12–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarron MO, Nicoll JAR, Stewart J, Ironside JW, Mann DMA, Love S, Graham DI, Grubb A. Absence of cystatin C mutation in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000;54:242–244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olafsson I, Grubb A. Hereditary cystatin C amyloid angiopathy. Amyloid. 2000;7:70–79. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palsdottir A, Snorradottir AO, Thorsteinsson L. Hereditary cystatin C amyloid angiopathy: Genetic, clinical, and pathological aspects. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:55–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur G, Levy E. Cystatin C in Alzheimer's disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy E, Sastre M, Kumar A, Gallo G, Piccardo P, Ghetti B, Tagliavini F. Codeposition of cystatin C with amyloid-beta protein in the brain of Alzheimer disease patients. J Neuropath Exp Neur. 2001;60:94–104. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mi WQ, Jung SS, Yu H, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Mathews PM, Tagliavini F, Levy E. Complexes of Amyloid-beta and Cystatin C in the Human Central Nervous System. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:273–280. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sastre M, Calero M, Pawlik M, Mathews PM, Kumar A, Danilov V, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Frangione B, Levy E. Binding of cystatin C to Alzheimer's amyloid beta inhibits in vitro amyloid fibril formation. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selenica ML, Wang X, Ostergaard-Pedersen L, Westlind-Danielsson A, Grubb A. Cystatin C reduces the in vitro formation of soluble A beta 1-42 oligomers and protofibrils. Scand J Clin Lab Inv. 2007;67:179–190. doi: 10.1080/00365510601009738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaeser SA, Herzig MC, Coomaraswamy J, Kilger E, Selenica ML, Winkler DT, Staufenbiel M, Levy E, Grubb A, Jucker M. Cystatin C modulates cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1437–1439. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mi W, Pawlik M, Sastre M, Jung SS, Radvinsky DS, Klein AM, Sommer J, Schmidt SD, Nixon RA, Mathews PM, Levy E. Cystatin C inhibits amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1440–1442. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tizon B, Ribe EM, Mi WQ, Troy CM, Levy E. Cystatin C Protects Neuronal Cells from Amyloid-beta-induced Toxicity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:885–894. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng A, Irizarry MC, Nitsch RM, Growdon JH, Rebeck GW. Elevation of cystatin C in susceptible neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61781-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun BG, Zhou YG, Halabisky B, Lo I, Cho SH, Mueller-Steiner S, Devidze N, Wang X, Grubb A, Gan L. Cystatin C-Cathepsin B Axis Regulates Amyloid Beta Levels and Associated Neuronal Deficits in an Animal Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron. 2008;60:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Sun BG, Zhou YG, Grubb A, Gan L. Cathepsin B Degrades Amyloid-beta in Mice Expressing Wild-type Human Amyloid Precursor Protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.371641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrahamson M, Dalboge H, Olafsson I, Carlsen S, Grubb A. Efficient Production of Native, Biologically-Active Human Cystatin-C by Escherichia-Coli. Febs Lett. 1988;236:14–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalboge H, Jensen EB, Tottrup H, Grubb A, Abrahamson M, Olafsson I, Carlsen S. High-Level Expression of Active Human Cystatin-C in Escherichia-Coli. Gene. 1989;79:325–332. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi M, Iwamoto S, Sato S, Sudo S, Takagi M, Sakai H, Hayakawa T. Efficient production of recombinant cystatin C using a peptide-tag, 4AaCter, that facilitates formation of insoluble protein inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. Protein Expres Purif. 2013;88:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, Zhao XZ, Xu XY, Tang B, Zha ZL, Zhang MX, Yao DW, Chen XX, Wu XH, Cao L, Guo HQ. Expression and purification of soluble human cystatin C in Escherichia coli with maltose-binding protein as a soluble partner. Protein Expres Purif. 2014;104:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou YJ, Zhou Y, Li J, Chen J, Yao YQ, Yu L, Peng DS, Wang MR, Su D, He Y, Gou LT. Efficient expression, purification and characterization of native human cystatin C in Escherichia coli periplasm. Protein Expres Purif. 2015;111:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Files D, Ogawa M, Scaman CH, Baldwin SA. A Pichia pastoris fermentation process for producing high-levels of recombinant human cystatin-C. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2001;29:335–340. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YM, Li DJ, Xu XJ, Cui M, Zhen HH, Wang Q. Effect of codon optimization on expression levels of human cystatin C in Pichia pastoris. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:4990–5000. doi: 10.4238/2014.July.4.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindahl P, Abrahamson M, Bjork I. Interaction of Recombinant Human Cystatin-C with the Cysteine Proteinases Papain and Actinidin. Biochem J. 1992;281:49–55. doi: 10.1042/bj2810049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krupa JC, Mort JS. Optimization of detergents for the assay of cathepsins B, L, S, and K. Anal Biochem. 2000;283:99–103. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Illy C, Quraishi O, Wang J, Purisima E, Vernet T, Mort JS. Role of the occluding loop in cathepsin B activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1197–1202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzmic P, Elrod KC, Cregar LM, Sideris S, Rai R, Janc JW. High-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors: Simultaneous determination of tight-binding inhibition constants and enzyme concentration. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:45–50. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JW, Morrison JF, Duggleby RG. Tight-Binding Inhibitors as Pseudo-Substrates of Dihydrofolate-Reductase. P Aust Biochem Soc. 1979;12:3–3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pallitto MM, Murphy RM. A mathematical model of the kinetics of beta-amyloid fibril growth from the denatured state. Biophys J. 2001;81:1805–1822. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berti PJ, Ekiel I, Lindahl P, Abrahamson M, Storer AC. Affinity purification and elimination of methionine oxidation in recombinant human cystatin C. Protein Expres Purif. 1997;11:111–118. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stadtman ER. Role of oxidant species in aging. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1105–1112. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ekiel I, Abrahamson M, Fulton DB, Lindahl P, Storer Ac, Levadoux W, Lafrance M, Labelle S, Pomerleau Y, Groleau D, LeSauteur L, Gehring K. NMR structural studies of human cystatin C dimers and monomers. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:266–277. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jankowska E, Wiczk W, Grzonka Z. Thermal and guanidine hydrochloride-induced denaturation of human cystatin C. Eur Biophys J Biophy. 2004;33:454–461. doi: 10.1007/s00249-003-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rzychon M, Chmiel D, Stec-Niemczyk J. Modes of inhibition of cysteine proteases. Acta Biochim Pol. 2004;51:861–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ekiel I, Abrahamson M. Folding-related dimerization of human cystatin C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1314–1321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrahamson M, Mason RW, Hansson H, Buttle DJ, Grubb A, Ohlsson K. Human Cystatin-C - Role of the N-Terminal Segment in the Inhibition of Human Cysteine Proteinases and in Its Inactivation by Leukocyte Elastase. Biochem J. 1991;273:621–626. doi: 10.1042/bj2730621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royer CA. Probing protein folding and conformational transitions with fluorescence. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1769–1784. doi: 10.1021/cr0404390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juszczyk P, Paraschiv G, Szymanska A, Kolodziejczyk AS, Rodziewicz-Motowidlo S, Grzonka Z, Przybylski M. Binding Epitopes and Interaction Structure of the Neuroprotective Protease Inhibitor Cystatin C with beta-Amyloid Revealed by Proteolytic Excision Mass Spectrometry and Molecular Docking Simulation. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2420–2428. doi: 10.1021/jm801115e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aldred AR, Brack CM, Schreiber G. The Cerebral Expression of Plasma-Protein Genes in Different Species. Comp Biochem Phys B. 1995;111:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(94)00229-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wahlbom M, Wang X, Lindstrom V, Carlemalm E, Jaskolski M, Grubb A. Fibrillogenic oligomers of human cystatin C are formed by propagated domain swapping. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18318–18326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.