Abstract

Exercising individuals commonly consume analgesics but these medications alter tendon and skeletal muscle connective tissue properties, possibly limiting a person from realizing the full benefits of exercise training. I detail the novel hypothesis that analgesic medications alter connective tissue structure and mechanical properties by modifying fibroblast production of growth factors and matrix enzymes, which are responsible for extracellular matrix remodeling.

Keywords: tendon, extracellular matrix, collagen, cross-linking, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, cyclooxygenase

INTRODUCTION

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAID, e.g. ibuprofen) and acetaminophen/paracetamol (APAP) has long been established as the standard of care for many pain-producing ailments including musculoskeletal pain, and are some of the most commonly consumed medications worldwide. Elderly individuals and osteoarthritic patients, who are encouraged to exercise to improve health, also use these over-the-counter analgesics extensively. Steroidal anti-inflammatory medications have also been commonly used to treat joint and tendon pain but their use has been questioned due to potential tendon damage and poor long-term pain relief (15). Not surprisingly, NSAIDs and APAP are the most common treatment options for individuals with exercise-induced tendon and skeletal muscle pain.

Tendons and the integrated connective tissue layers of skeletal muscle are an essential component of normal musculoskeletal function. Surprisingly, tendons were once thought to be inert structures but we now know that acute and chronic exercise induces changes in tendon as well as skeletal muscle connective tissue properties. For example, loading of tendon or skeletal muscle during exercise increases production of several growth factors and enzymes that regulate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling (14). Exercise-induced ECM remodeling presumably contributes to chronic exercise adaptations such as increased tendon cross-sectional area (CSA) and connective tissue stiffness (16). An increase in the stiffness of connective tissue likely improves skeletal muscle power output, rate of torque development, and performance of functional tasks (4). For example, Bojsen-Møller et al. (4) have demonstrated that rate of torque development and muscle power during dynamic movements (e.g. squat jump) positively correlate with connective tissue stiffness. Interestingly, several human (6, 9, 11) and animal (7, 8) studies have demonstrated that acute and chronic consumption of common over-the-counter analgesic medications alter tendon and skeletal muscle ECM structure and reduce tendon stiffness. In vitro work offers the possibility that these analgesic-induced changes in tissue structure and function are related to a disregulation of key growth factors and enzymes that modulate ECM remodeling (28-30).

The ability of analgesic medication to influence connective tissue ECM and mechanical properties could have a significant impact on musculoskeletal function, in particular if these drugs impact adaptations to exercise training. A reduction in tendon stiffness may reduce the ability to transfer force from muscle to bone and impair performance of functional tasks. Limiting connective tissue adaptations during exercise training may also increase the risk of tendon or skeletal muscle connective tissue injury because of the greater load placed on connective tissue structures subsequent to the greater force producing ability of skeletal muscle (6, 23). Furthermore, resistance exercise training is emerging as a viable therapeutic option for chronic tendon pain (15) and it is not known if these medications influence the effectiveness of exercise therapy.

With the widespread use of analgesic medications in exercising individuals and the important role of tendon and skeletal muscle connective tissue in musculoskeletal function, a review of the potential impact of analgesics on connective tissue is needed. In this review I detail the novel hypothesis that analgesic medications alter connective tissue structure and mechanical properties by modifying fibroblast production of growth factors and matrix enzymes, which are responsible for extracellular matrix remodeling. In order to provide a platform to discuss this hypothesis, a brief historical review of relevant work will be discussed and the impact of exercise on ECM remodeling will be briefly highlighted. This review has implications for a wide spectrum of populations including athletes, elderly people, and the recreational exerciser.

EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX: A BASIC REVIEW

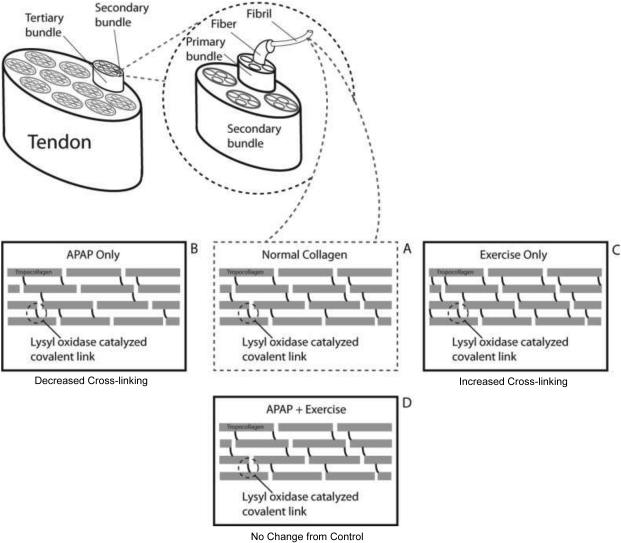

The extracellular matrix of tendon and skeletal muscle consists mainly of type I collagen fibers surrounded by an aqueous matrix of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans (14). In tendon, collagen forms 60-80% of tendon’s dry weight and is organized into parallel bundles of collagen fibrils (Figure 1). Oxidation of lysine and hydroxylysine by lysyl oxidase (LOX) forms cross-links within collagen fibrils (Figure 1 and 2), which increase the tensile strength of tendon and stabilize the collagen fibril assembly. In addition to its presence in tendon, collagen is an essential component of skeletal muscle ECM. In skeletal muscle, collagen forms the basis of the connective tissue sheaths, which envelop each layer of skeletal muscle. These connective tissue sheaths provide structural support but also facilitate the transfer of force generated in skeletal muscle fibers to tendon and bone.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of collagen fibril organization and cross-linking emphasizing the effect of APAP and exercise on rat Achilles tendon cross-linking (8). Panel A presents an example of normal tendon collagen with lysyl oxidase catalyzed cross-links connecting tropocollagen molecules. Panel B highlights the effect of chronic APAP consumption on Achilles tendon collagen cross-linking in non-exercising rats. Panel C highlights the effect of chronic exercise training on Achilles tendon collagen cross-linking. Chronic APAP consumption results in a reduction in collagen cross-linking. In contrast, chronic exercise training leads to an increase in collagen cross-linking in the Achilles tendon. Panel D highlights the combined effect of chronic exercise and APAP consumption. Effectively, the combination of exercise and APAP results in a tendon with normal levels of collagen cross-linking. APAP does not appear to blunt the effect of exercise on cross-linking. Similar effects of APAP on non-exercised skeletal muscle cross-linking have been noted (7).

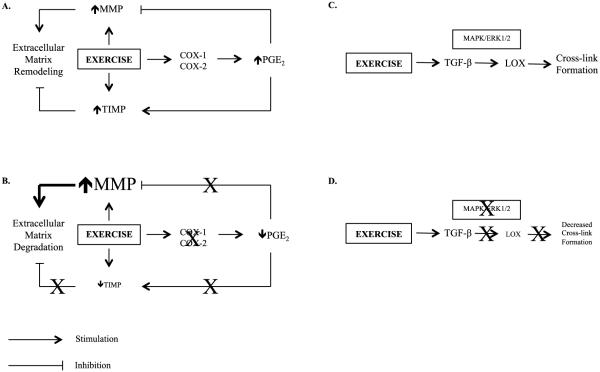

Figure 2.

Schematic representation highlighting the novel hypothesis that some analgesic medications alter extracellular matrix remodeling and tissue mechanical properties by modifying fibroblast production of growth factors and matrix enzymes. Emphasis is placed on known and potential targets of APAP and possibly other COX-inhibiting drugs. Panel A: Impact of exercise on PGE2, MMPs, TIMPS, and ECM remodeling when no analgesics are consumed. Exercise increases activity of both MMPs and TIMPs, while PGE2, via COX, limits the increase in MMPs but enhances activation of TIMPs. Panel B: Impact of exercise on PGE2, MMPs, TIMPS, and ECM remodeling during chronic consumption of analgesics. I hypothesize that inhibition of PGE2 may result in excess extracellular matrix degradation due to lack of inhibition of MMPs and reduced activation of TIMPs leading to an environment favoring ECM degradation. Panel C: Regulation of cross-link formation when no analgesics are consumed. TGF-β, via MAPK/ERK1/2, stimulates LOX activity and cross-link formation, an effect that is enhanced by exercise. Panel D: Activation of LOX and cross-link formation during chronic consumption of analgesics. I hypothesize that some analgesics inhibit MAPK/ERK1/2, and possibly other signaling molecules, leading to reduced LOX activity and reduced cross-link formation. I hypothesize that the analgesic-induced ECM degradation and reduce cross-link formation contribute to reductions in connective tissue stiffness. Cyclooxygenase (COX), Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase (TIMP), Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β), Lysyl Oxidase (LOX), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK), Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase (ERK1/2).

Tendon and skeletal muscle ECM remodeling is regulated by a large family of enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which degrade the ECM (Figure 2). In turn, MMPs are reversibly inhibited by a group of enzymes, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Additionally, tendon proteoglycans, a large family of proteins, can bind collagen and regulate collagen formation and maturation and alter the tensile properties of tendon. A fairly homogeneous population of fibroblastic cells resides between collagen fibrils and likely have a role in exercise adaptations in tendon and skeletal muscle (14). These fibroblastic cells secrete numerous cytokines and growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), interlukin-6 (IL-6), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). These cytokines and growth factors function to regulate ECM remodeling. For example, IL-6 and IGF-1 stimulate tendon collagen synthesis (2, 14) and IGF-1 is associated with an increase in tendon mass. Additionally, PGE2 may regulate MMP/TIMP production [Figure 2, (12)]. TGF-β also appears to have an important role in regulating LOX activity [Figure 2, (32)] and proteoglycan turnover.

EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX REMODELING WITH EXERCISE

The impact of exercise on skeletal muscle mass and strength have been well documented but the potential positive benefits of exercise training on tendon and skeletal muscle connective tissue is often overlooked. Several studies in animals and humans have evaluated the effects of various exercise-training regimens on tendon and skeletal muscle mechanical properties and extensive reviews have been published previously (e.g, (14)). Several methodological differences confound cross-study comparisons but work by Kongsgaard et al. (16) indicate that chronic resistance training can induce tendon hypertrophy and increase tendon stiffness. Skeletal muscle connective tissue stiffness may also increase with chronic exercise training.

Although direct links between acute exercise response and chronic connective tissue adaptations have not been extensively established, exercise upregulates fibroblasts production of an array of cytokines and growth factors (11, 14), such as IL-6 and IGF-1, which likely contribute to exercise-induced ECM remodeling. Exercise also increases proliferation of fibroblasts and tendon stem cells (33). MMP’s and TIMP’s are increased with exercise (Figure 2) and alterations in the activity of various MMPs and/or TIMP’s may play a role in driving ECM remodeling during exercise training (14). Collagen and proteoglycans are degraded by MMPs and alterations in the activity of various MMPs and/or TIMP’s may also have a role in regulating ECM remodeling during exercise training (14). For example, MMP-2 is increased with exercise and appears to be counter-regulated by an increase in the inhibitory actions of TIMP-1 and -2 (14). PGE2 is also increased with exercise (17) and may limit the induction of MMPs [(12), Figure 2]. Tendon collagen synthesis is increased with exercise in young individuals (19) and may contribute to chronic tendon adaptions (14), including increased tendon stiffness and CSA. Exercise is also a potent stimulator of skeletal muscle collagen synthesis (19), which may contribute to increased skeletal muscle collagen content with chronic training (7).

Many studies of isolated fibroblasts exposed to cyclic strain (33) suggest the strain placed on tendons and skeletal muscle is the likely stimulus for fibroblast production of cytokines and growth factors with exercise. However, the exact mechanisms of mechanoregulation of fibroblasts in tendon and skeletal muscle have not been fully defined. Additionally, the interpretation of in vitro work is limited. In many cases, strain is applied for hours or days, which does not mimic the in vivo situation. Additionally, the strain applied is often excessive and non-physiological. In vivo validation of cell culture work is needed before strong clinical conclusions can be made.

ANALGESIC MEDICATIONS ALTER CONNECTIVE TISSUE STRUCTURE AND MECHANICAL PROPERTIES

Few, mostly in vitro studies have provided evidence that some analgesics, specifically, inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (COX), alter fibroblast/tenocyte properties. Prostaglandins, the downstream products of COX enzymes, are important for modulating pain and inflammation, thus these enzymes are the target of many analgesic medications, including ibuprofen and several COX-2 specific inhibitors. There are two commonly known isoforms of COX: COX-1 (variant 1 and 2) and COX-2. It is generally understood that COX-1 is constitutively expressed and helps maintain the normal homeostatic functions in human tissues, whereas COX-2 is inducible and is more involved with inflammatory responses in tissues. In contrast, both COX-1 and COX-2 are constitutively expressed in human tendon and skeletal muscle (23, 24). COX-2 appears to be involved with tendon healing (20) and with several non-pathologic responses in tendon (6). The role of COX-1 and COX-2 in regulating tendon and skeletal muscle connective tissue adaptations with exercise training has not been extensively studied, but animal and cell culture studies suggest that these enzymes are important in the regulation of ECM remodeling.

Early animal work by Vogel (31) demonstrated that 10-day treatment of young rats with the non-selective COX inhibitor indomethacin increased the tensile strength of tail tendons in a dose-dependent manner. The increase in tensile strength was accompanied by a dose-dependent increase in total and insoluble collagen content (31). The findings of Vogel were partially confirmed with later work in rabbits by Carlstedt et al. (5). Treatment of rabbits with indomethacin for 16-weeks lead to an increase in the tensile strength of the plantaris longus tendon but collagen content was not altered with drug consumption (5). Shorter durations of drug treatment (4- and 8-weeks) did not alter tendon properties (5). Later work using fibroblast culture models seemed to suggest that COX inhibitors actually inhibit tendon cell proliferation and upregulate the expression of matrix degrading enzymes. Riley et al. (22) demonstrated that when human tendons are cultured in the presence of common non-selective COX inhibitors [indomethacin (20 μg/ml) or naproxen (100 μg/ml), tendon cell proliferation and glycosoaminoglycan synthesis was reduced compared to controls. Similar findings were noted in cells cultured from rat Achilles tendons in the presence of the non-selective COX inhibitor ibuprofen (30). Ibuprofen (up to 400 μg/ml), in a dose-dependent manner, inhibited tendon cell proliferation, an effect that appeared to be due to inhibition of cell cycle progression (30). Treatment of tendon cells with ibuprofen also resulted in the upregulation several MMP’s (28). Similar effects on tendon cell proliferation were noted when cells were treated (up to 8 μg/ml) with the COX-2 specific inhibitor celecoxib (29). Interestingly, neither ibuprofen nor celecoxib altered the expression of type I or III collagen (28, 29) but additional work demonstrated that higher concentrations of indomethacin (100 and 200 μg/ml) inhibit tendon cell proliferation while also inhibiting collagen formation (35). More recent work, evaluated the effect of celecoxib on recently discovered tendon-derived stem cells. Celecoxib (10 and 100 μg/ml) inhibited tenocyte differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells but did not alter cell proliferation (34). Celecoxib treatment was also associated with a reduction in collagen I and III as well as several transcription factors including scleraxis and tenomodulin, a marker of tenocyte differentiation (34). Treatment of tendon cells with indomethacin (8.9 μg/ml) in vitro also blocked the increase in tenocyte PGE2 production after cells were stimulated with repetitive motion (1). As with some of the in vitro cell strain studies mentioned above, little work has been done in vivo to validate in vitro findings. Additionally, in many of the in vitro studies, cells are incubated in progressively higher drug concentrations until an effect was noted. The clinical relevance of some of the doses used in vitro is unclear. These in vitro and limited animal studies provide evidence that analgesic medications, mainly COX inhibitors, can influence tendon cells and may inhibit collagen synthesis and the production of key molecules that are necessary of exercise-induced tendon remodeling.

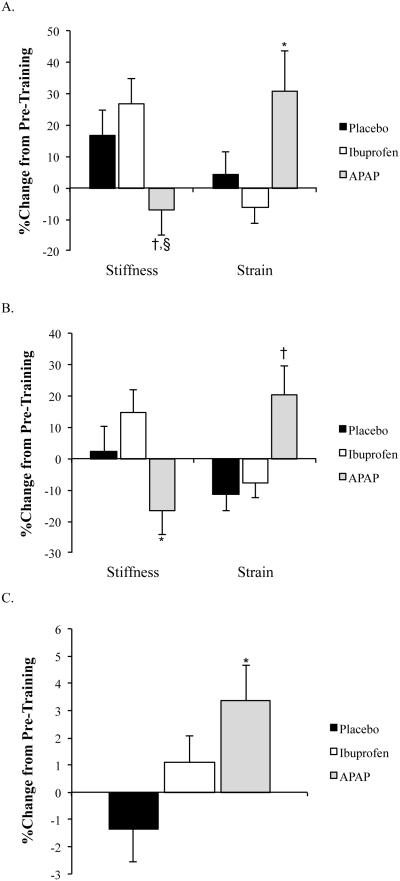

Initial human studies by Trappe et al. (25, 27) evaluating the influence of analgesics on exercise-induced increases in skeletal muscle protein synthesis are what spurred our work into the effects of analgesics on tendon. Prior to the year 2000, it was known that prostaglandins played a key role in regulating skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Based on these data, Trappe et al. (25, 27) evaluated the effects of APAP and ibuprofen on exercise-induced skeletal muscle protein synthesis and prostaglandin production. They hypothesized that ibuprofen would inhibit exercise-induced increases in protein synthesis and prostaglandin production while APAP, which, at the time, was thought to act only in the CNS, would have no effect on skeletal muscle. Surprisingly, both drugs inhibited skeletal muscle protein synthesis and prostaglandin production (25, 27). These initial studies involved short-term drug exposure but raised the question as to whether chronic consumption of APAP or ibuprofen would have similar effects. At the same time, based on evidence from cell culture and animal studies (described above) and the ability of APAP and ibuprofen to inhibit prostaglandins (25), it was hypothesized that APAP and ibuprofen would also limit tendon adaptations to chronic exercise (6). Subjects consumed maximum daily doses of ibuprofen (1200 mg/d), APAP (4000 mg/d), or placebo over a period of 12-weeks in conjunction with resistance training (6, 23). Unexpectedly, consumption of either ibuprofen or APAP enhanced the anabolic effects of training leading to greater increases in skeletal muscle mass when compared to the placebo group (23). Exercise also increased peak patellar tendon stiffness but not tendon CSA in the placebo treated group [Figures 3, (6)]. In contrast to skeletal muscle, ibuprofen had no effect on tendon tensile properties (6). Instead, patellar tendon CSA increased in individuals consuming APAP (Figure 3). Increased tendon CSA is often associated with an increase in tendon stiffness. Remarkably, patellar tendon stiffness declined with training in older adults consuming APAP and tendon strain was substantially increased for any load placed on the tendon [Figure 3, (6)]. While the clinical consequences of increasing muscle strength without altering tendon stiffness is not clear, a large discrepancy between adaptations in skeletal muscle and tendon could predispose individuals to musculoskeletal injuries. The large reduction in tendon stiffness noted by Carroll et al. (6) could significantly impact the rate of torque development and peak power output (4). It is also important to note that the duration of the Carroll et al. (6) investigation was only 12 weeks. In many cases osteoarthritis patients can be using APAP for several years, which could result in a further decline in tendon stiffness and skeletal muscle function. Additionally, the lower patellar tendon stiffness, even with an increase in tendon CSA, suggests that the ECM of the tendon was altered by the chronic use of APAP.

Figure 3.

A) Percent change in patellar tendon mechanical properties at peak tendon force after 12-weeks of resistance training in older adults. *p≤0.05, APAP vs. placebo and ibuprofen, †p<0.05, APAP vs. ibuprofen, §p=0.057, APAP vs. placebo. B) Percent change in patellar tendon mechanical properties compared at a common tendon force after 12-weeks of resistance training in older adults. *p<0.05, APAP vs. ibuprofen, †p<0.05, APAP vs. placebo and ibuprofen. C. Percent change in mean patellar tendon cross-sectional area (CSA). *p<0.05, APAP vs. placebo. Data presented as mean±standard error. For additional details on subject characteristics and drug dosing refer to Carroll et al. (6). [Adapted from (6). Copyright © 2011 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.]

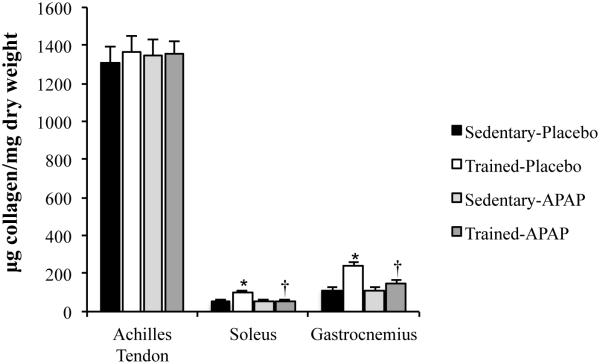

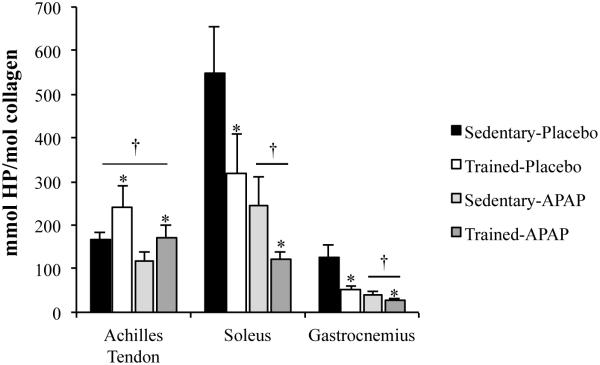

Our laboratory has followed up on Dr. Trappe’s work (6, 23, 25, 27) with a primary focus on the effects of APAP on tendon and skeletal muscle ECM (7, 8, 11). Using animal models and human studies, we have completed initial work evaluating changes in tendon and skeletal muscle ECM following acute and chronic exercise with APAP consumption. In rats, we evaluated the impact of daily APAP consumption (200 mg/kg, human equivalent ~40 mg/kg) during chronic treadmill exercise on tendon and skeletal muscle collagen and cross-linking content with contrasting results (7, 8). In the Achilles tendon, neither exercise training nor APAP altered collagen content (Figure 4). In contrast, exercise lead to an increase in Achilles tendon collagen cross-linking, an effect that was not altered by APAP [Figure 5 (8)]. However, collagen cross-linking content was lower in rats given APAP regardless of activity level (Figure 1 and 5). These findings provide evidence that reductions in cross-link formation may have contributed to the mechanical findings noted in humans chronically using APAP (6). Interestingly, water content was also lower in the Achilles tendon of animals given APAP, which could result in strain rate-dependent changes in tendon elongation and stiffness. As with the Achilles tendon, gastrocnemius and soleus water content and cross-linking were lower in APAP-treated animals regardless of activity level [Figure 5 (7)]. However, in contrast to the Achilles tendon, skeletal muscle collagen content increased ~2-fold with training, an effect that was not seen in animals given APAP (Figure 4). The large increase in skeletal muscle content is in stark contrast to the Achilles tendon in which collagen content was not greater in exercise-trained animals (8).

Figure 4.

Tissue collagen content normalized to tissue dry weight. *p<0.05, Sedentary-Placebo versus Trained-Placebo. †p<0.05, Trained-Placebo versus Trained-APAP. Data presented as mean±standard error. [Adapted from (7). Copyright © 2015 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.] [Adapted from (8). Copyright © 2012 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.]

Figure 5.

Tissue hydroxylyslpyridinoline (HP) content normalized to collagen content. *p<0.05, main effect for exercise, †p<0.05, main effect for drug. [Adapted from (7). Copyright © 2015 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.] [Adapted from (8). Copyright © 2012 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.]

The differing effect of APAP on skeletal muscle and tendon collagen may be related to exposure of each tissue to APAP or differences in the sensitivity of each tissue to COX inhibition. After an oral dose of APAP (1000 mg), levels of APAP in skeletal muscle interstitial fluid peak at values ~2-3 times higher than levels noted in the Achilles peritendinous space (11). In fact the peak concentration of APAP in the space surrounding the Achilles tendon is approximately the IC50 value for APAPs ability to inhibit COX-2 ex vivo (13). Furthermore, these values are only achieved for ~1-hour and then APAP values fall below the IC50 for COX-2 inhibition. Interestingly, the RNA levels of COX-1 and COX-2 are ~2-fold higher in tendon when compared to skeletal muscle (24), which may also influence the extent of inhibition with various analgesic medications.

Chronic training has also been shown to increase skeletal muscle stiffness in some models (10). There is a strong positive correlation between skeletal muscle stiffness and collagen content (10), suggesting that the loss of collagen observed in APAP-treated trained rats, in conjunction with loss of cross-links, may have led to a reduction in skeletal muscle stiffness. Such a hypothesis requires further study including measures of tissue mechanical properties. Additionally, work is needed in order to determine if similar changes in collagen and cross-linking are seen in humans chronically consuming APAP or other COX-inhibiting analgesics. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that APAP, and possibly other analgesic medications, have strong effects on connective tissue ECM, which are not limited to tendon and are tissue-specific. Also intriguing is the fact that, in contrast to cross-linking, which seems to be reduced by APAP in skeletal muscle and tendon regardless of exercise, the effect of APAP on skeletal muscle collagen is dependent on exercise training. The tissue-specific effect of APAP on collagen could be due to differences in tissue concentration of APAP noted above. The lower concentration of drug realized in the tendon may not be sufficient to alter MMP activity or collagen synthesis. A similar logic may explain the lack of change in patellar tendon properties in humans chronically consuming ibuprofen (6). Further investigation of the mechanisms contributing to the effects of exercise and APAP, and other COX inhibitors, on skeletal muscle collagen formation is warranted, especially given the strong impact of collagen on skeletal muscle function.

ANALGESIC MEDICATIONS MODIFY FIBROBLAST PRODUCTION OF GROWTH FACTORS AND MATRIX ENZYMES

Collagen

Very few studies have evaluated detailed mechanisms contributing to the effects of various analgesics on tendon or skeletal muscle ECM. Some insight can be gained by considering the established mechanism of action of analgesic medications. As discussed above, the target of traditional NSAIDs is known to be COX, the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of prostaglandins. Many common NSAIDs are non-specific inhibitors of COX-1 and -2 while recent work suggests that APAP is a potent and specific COX-2 inhibitor (13). Although the rational for blocking prostaglandins to reduce pain is sound, COX-inhibitors provide a general inhibition of COX and thus the production of any downstream prostaglandins are likely blunted. One of the most studied prostaglandins in tendon and fibroblasts is PGE2. Although the exact role of PGE2 in regulating ECM remodeling is far from clear, tendon production of PGE2 is increased with exercise or cell stretching (1, 17) while basal and exercise-induced increases in tendon and skeletal muscle PGE2 are blunted with exposure to COX inhibitors (9, 17, 25). In non-tendon models, PGE2 has been shown to modulate the production of matrix degrading MMPs and their inhibitors TIMPs. Specifically, PGE2 may downregulate MMP production, while enhancing TIMP production [(12), Figure 2]. More importantly, non-selective (ibuprofen) and COX-2 selective (rofecoxib) inhibition leads to excessive production of MMPs in tendon cell culture (28) and other models (12). Although additional mechanistic studies are needed, I hypothesize that the effect of APAP and other COX inhibitors on ECM may be medicated by an excessive upregulation of collagen degrading MMPs due to inhibition of COX and PGE2 production (Figure 2).

In addition to the possible impact of COX inhibition on MMPs, some analgesic medication may blunt collagen synthesis but limited data is equivocal. In humans, administration of indomethacin during acute bouts of exercise has been shown to reduce markers [procollagen I intact N-terminal propeptide (PINP)] of tendon collagen synthesis (9) and decrease tendon blood flow (17). In contrast, ibuprofen consumption in humans did not alter patellar tendon collagen fractional synthesis rates before or after an acute bout of kicking exercise (21). The lack of an effect of ibuprofen on tendon collagen synthesis is supported by Dr. Trappe’s work (6) in which ibuprofen did not alter tendon CSA. Additionally, chronic APAP consumption in rats did not alter total collagen content in the Achilles tendon (8), thus it seems that the acute effects of COX inhibition on tendon collagen synthesis may not translate into chronic effects on tendon collagen content. In contrast, as already mentioned, exercise had a strong impact on skeletal muscle collagen formation in rats, an effect that was negated in animals consuming APAP (7). More specific studies evaluating the impact of APAP and other COX inhibitors on collagen synthesis are needed, especially with controls for exercise bout and drug-type utilized.

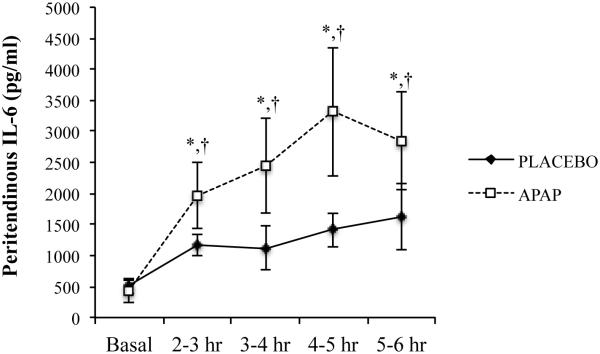

In order to gain further insight into the mechanisms contributing to the effects of the COX-2 inhibitor APAP on tendon, our laboratory has utilized microdialysis to evaluate the effects of APAP consumption on tendon IL-6 production after exercise. Acute exercise results in a rapid increase in peritendinous IL-6 levels (11). IL-6 can stimulate tendon collagen synthesis (2) and is required for maintaining normal tendon size and function. Interestingly, we found (11) that APAP consumption enhanced the exercise-induced increase in peritendinous IL-6 (Figure 6). A similar increase in the production of IL-6 has also been noted during administration of COX inhibitors in other models (12). Given the substantial augmentation of IL-6 release by APAP, it would seem likely that APAP enhanced collagen turnover after exercise. In contrast, as mentioned above, administration of a non-selective COX inhibitor (indomethacin) blunted PINP release in tendon (9). Direct comparisons between our work and Christensen et al. (9) are difficult because our measurement of IL-6 was completed only a few hours after exercise whereas PINP in Christensen et al. (9) was not evaluated until 24 hours post-exercise when IL-6 was likely no longer elevated. Interestingly, similar acute effects of IL-6 in response to COX inhibitor consumption have been noted in human skeletal muscle (18). Although acute COX inhibitor consumption seems to exacerbate the IL-6 response to exercise, chronic APAP consumption limited training-induced increases in skeletal muscle IL-6 mRNA expression (26), suggesting that the enhancement of IL-6 after exercise may be short-lived. Now that IL-6 has been identified as a potential mediator of APAP-induced effects on tendon, further chronic studies are needed to ascertain the long-term impact of COX inhibition on IL-6 levels while also clarifying the effect of chronic elevations in IL-6 on tendon structure and function, especially in in vivo models. Additionally, several next generation anti-inflammatory medications, such as tocilizumab and anakinra have been approved for use in humans. These new compounds are designed to antagonize cytokine receptors such as IL-6 and IL-1β. Given the vital role that cytokines such as IL-6 appear to play in normal ECM remodeling at rest and during exercise training, it seems likely that these receptor antagonists may interfere with normal connective adaptations to exercise training.

Figure 6.

Peritendinous IL-6 after an acute bout of treadmill exercise with or without APAP consumption. X-axis indicates time post-exercise. Samples were collected via microdialysis in 60-minute aliquots. *p<0.05. [Adapted from (11). Copyright © 2013 The American Physiological Society. Used with permission.]

Cross-linking

In addition to collagen, APAP consumption in rats leads to a large reduction in the number of cross-links per amount of collagen in both tendon and skeletal muscle (7, 8). The mechanism(s) contributing to the effect of APAP is not known but may involve APAP inhibition of LOX activity, although regulation of LOX activity is not well studied in whole tendon or skeletal muscle using in vivo experiments. The effect of APAP on cross-linking was similar in both tendon and skeletal muscle (7, 8), suggesting a common mechanism by which APAP inhibits cross-linking. Recent reports (3) do clearly demonstrate that APAP can alter phosphorylation of several signaling pathways, including p-38-MAPK and ERK1/2, which may have a role in the regulation of collagen (14) and LOX mediated cross-link formation (32). Specifically, TGF-β appears to be a key molecule in the regulation of ECM in response to exercise. Loading of tendon increases the expression of TGF-β (14), which mediates the effects of LOX on collagen fibril cross-linking (32). Both p-38-MAPK and ERK1/2 are involved in the stimulation of LOX by TGF-β (32) and may be inhibited by APAP (3), which I hypothesize could account for the lower levels of collagen cross-linking in both tendon and skeletal muscle after chronic APAP consumption (Figure 2).

SUMMARY AND IMPLICATIONS

There are still several unresolved questions from the body of work described above, which have significant clinical implications. First, the detailed mechanisms contributing to the drug-induced changes in tendon and skeletal muscle ECM remain largely unknown. Further defining the mechanisms contributing to the effect of analgesics may lead to new uses for these already important medications. Second, it is not clear why APAP, which was thought to act largely in the CNS (rather than peripheral tissues), would have such dramatic effects on collagen and cross-linking. The findings described in this review suggest that clinical practice may benefit from more detailed studies evaluating the extent to which APAP, and possibly other COX-inhibiting analgesics, impacts peripheral tissues. Lastly, further work is needed in order to resolve the apparent tissue-specific effects of some analgesics.

Although an analgesics-induced reduction in tissue stiffness could have negative implications for healthy individuals, a reduction in tissue collagen and stiffness could be beneficial in certain patient populations. Collagen cross-linking is substantially elevated in tendons of older adults and our findings suggest that APAP may reduce cross-linking in tendon and skeletal muscle (6-8), which may be a healthy adaptation in older adults. Tissue stiffness is also thought to be elevated in diabetic patients, thus APAP or other COX inhibitors may reduce tissue stiffness in these patients by blunting cross-link formation. Lastly, skeletal muscle fibrosis is common in several disorders, thus novel application of COX-inhibitors to reduce collagen and tissue stiffness should be considered in various patient populations.

In summary, ample evidence suggests that APAP, and possibly other COX inhibitors, limit exercise-induced increases in skeletal muscle or tendon collagen and collagen cross-linking and reduced tendon stiffness. The clinical impact of the effects of analgesics on tendon and skeletal muscle connective tissue are unclear but large reductions in tendon stiffness and changes in the ratio of collagen fibrils to cross-linking could impair physical function, especially since chronic consumption of these medications facilities skeletal muscle hypertrophy (23). The use of analgesics during exercise training should be considered in the context of balancing pain-reduction with performance adaptations and possible reductions in connective tissue stiffness.

Summary: Analgesics medications alter tendon and skeletal muscle extracellular matrix remodeling and may limit tendon and skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would also like to thank Todd Trappe, PhD who started much of this work in skeletal muscle ~15 years ago. Some of the work highlighted in this review was completed during my post-doctoral work with Dr. Trappe, which was funded by NIH R01-AG-020532 to Dr. Trappe and a Post-Doctoral Initiative Award from the American Physiological Society to C.C. Carroll. Much of the work highlighted in this review could not have been completed without the generous intramural support from Midwestern University. I would also like to extend my sincere appreciation to Broc Astill for generating Figure 1 and Jared Dickinson, PhD for critical review of the manuscript.

Disclosure of Funding: Some of the work highlighted in this review was completed while the author was a post-doctoral fellow with Todd Trappe, PhD and was funded by NIH R01-AG-020532 to Dr. Trappe and an American Physiological Society Post-Doctoral Initiative Award to the author. Much of the work highlighted in this review could not have been completed without the generous intramural support from Midwestern University.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Almekinders LC, Banes AJ, Ballenger CA. Effects of repetitive motion on human fibroblasts. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(5):603–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen MB, Pingel J, Kjaer M, Langberg H. Interleukin-6: a growth factor stimulating collagen synthesis in human tendon. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110(6):1549–54. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00037.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blough ER, Wu M. Acetaminophen: beyond pain and Fever-relieving. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:72. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojsen-Moller J, Magnusson SP, Rasmussen LR, Kjaer M, Aagaard P. Muscle performance during maximal isometric and dynamic contractions is influenced by the stiffness of the tendinous structures. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(3):986–94. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01305.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlstedt CA, Madsen K, Wredmark T. The influence of indomethacin on biomechanical and biochemical properties of the plantaris longus tendon in the rabbit. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;106(3):157–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00452202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll CC, Dickinson JM, LeMoine JK, et al. Influence of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on in vivo patellar tendon adaptations to knee extensor resistance exercise in older adults. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(2):508–15. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01348.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll CC, Martineau K, Arthur KA, Huynh RT, Volper BD, Broderick TL. The effect of chronic treadmill exercise and acetaminophen on collagen and cross-linking in rat skeletal muscle and heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308(4):R294–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00374.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll CC, Whitt JA, Peterson A, Gump BS, Tedeschi J, Broderick TL. Influence of acetaminophen consumption and exercise on Achilles tendon structural properties in male Wistar rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302(8):R990–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00659.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen B, Dandanell S, Kjaer M, Langberg H. Effect of anti-inflammatory medication on the running-induced rise in patella tendon collagen synthesis in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110(1):137–41. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00942.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducomps C, Mauriege P, Darche B, Combes S, Lebas F, Doutreloux JP. Effects of jump training on passive mechanical stress and stiffness in rabbit skeletal muscle: role of collagen. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;178(3):215–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gump BS, McMullan DR, Cauthon DJ, et al. Short-term acetaminophen consumption enhances the exercise-induced increase in Achilles peritendinous IL-6 in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115(6):929–36. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00219.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamza M, Dionne RA. Mechanisms of non-opioid analgesics beyond cyclooxygenase enzyme inhibition. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2009;2(1):1–14. doi: 10.2174/1874467210902010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in man. FASEB J. 2008;22(2):383–90. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8506com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjaer M. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):649–98. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kongsgaard M, Kovanen V, Aagaard P, et al. Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(6):790–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kongsgaard M, Reitelseder S, Pedersen TG, et al. Region specific patellar tendon hypertrophy in humans following resistance training. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;191(2):111–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langberg H, Boushel R, Skovgaard D, Risum N, Kjaer M. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 mediated prostaglandin release regulates blood flow in connective tissue during mechanical loading in humans. J Physiol. 2003;551:683–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046094. Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikkelsen UR, Schjerling P, Helmark IC, et al. Local NSAID infusion does not affect protein synthesis and gene expression in human muscle after eccentric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(5):630–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller BF, Olesen JL, Hansen M, et al. Coordinated collagen and muscle protein synthesis in human patella tendon and quadriceps muscle after exercise. J Physiol. 2005;567:1021–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093690. Pt 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oak NR, Gumucio JP, Flood MD, et al. Inhibition of 5-LOX, COX-1, and COX-2 increases tendon healing and reduces muscle fibrosis and lipid accumulation after rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2860–8. doi: 10.1177/0363546514549943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen SG, Miller BF, Hansen M, Kjaer M, Holm L. Exercise and NSAIDs: effect on muscle protein synthesis in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(3):425–31. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f27375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley GP, Cox M, Harrall RL, Clements S, Hazleman BL. Inhibition of tendon cell proliferation and matrix glycosaminoglycan synthesis by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in vitro. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26(3):224–8. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trappe TA, Carroll CC, Dickinson JM, et al. Influence of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(3):R655–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00611.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trappe TA, Carroll CC, Jemiolo B, et al. Cyclooxygenase mRNA expression in human patellar tendon at rest and after exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(1):R192–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00669.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trappe TA, Fluckey JD, White F, Lambert CP, Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle PGF(2)(alpha) and PGE(2) in response to eccentric resistance exercise: influence of ibuprofen acetaminophen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(10):5067–70. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trappe TA, Standley RA, Jemiolo B, Carroll CC, Trappe SW. Prostaglandin and myokine involvement in the cyclooxygenase-inhibiting drug enhancement of skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304(3):R198–205. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00245.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trappe TA, White F, Lambert CP, Cesar D, Hellerstein M, Evans WJ. Effect of ibuprofen and acetaminophen on postexercise muscle protein synthesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282(3):E551–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00352.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chang HN, Lin YC, Lin MS, Pang JH. Ibuprofen upregulates expressions of matrix metalloproteinase-1, -8, -9, and -13 without affecting expressions of types I and III collagen in tendon cells. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(4):487–91. doi: 10.1002/jor.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chou SW, Chung CY, Chen J, Pang JH. Effects of celecoxib on migration, proliferation and collagen expression of tendon cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2007;48(1):46–51. doi: 10.1080/03008200601071295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai WC, Tang FT, Hsu CC, Hsu YH, Pang JH, Shiue CC. Ibuprofen inhibition of tendon cell proliferation and upregulation of the cyclin kinase inhibitor p21CIP1. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(3):586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel HG. Mechanical and chemical properties of various connective tissue organs in rats as influenced by non-steroidal antirheumatic drugs. Connect Tissue Res. 1977;5(2):91–5. doi: 10.3109/03008207709152235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voloshenyuk TG, Landesman ES, Khoutorova E, Hart AD, Gardner JD. Induction of cardiac fibroblast lysyl oxidase by TGF-beta1 requires PI3K/Akt, Smad3, and MAPK signaling. Cytokine. 2011;55(1):90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JH, Guo Q, Li B. Tendon biomechanics and mechanobiology--a minireview of basic concepts and recent advancements. J Hand Ther. 2012;25(2):133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2011.07.004. quiz 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang K, Zhang S, Li Q, et al. Effects of celecoxib on proliferation and tenocytic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450(1):762–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Wang X, Qiu Y, Cornish J, Carr AJ, Xia Z. Effect of indomethacin and lactoferrin on human tenocyte proliferation and collagen formation in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;454(2):301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]