Abstract

A vaccine to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections is a national priority. Investigational vaccines have targeted the viral glycoprotein B (gB) as an inducer of neutralizing antibodies and phosphoprotein 65 (pp65) as an inducer of cytotoxic T cells. Antibodies to gB neutralize CMV entry into all cell types but their potency is low compared to antibodies that block epithelial cell entry through targeting the pentameric complex (gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131). Hence, more potent overall neutralizing responses may result from a vaccine that combines gB with pentameric complex-derived antigens. To assess the ability of pentameric complex subunits to generate epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies, DNA vaccines encoding UL128, UL130, and/or UL131 were formulated with Vaxfectin®, an adjuvant that enhances antibody responses to DNA vaccines. Mice were immunized with individual DNA vaccines or with pair-wise or trivalent combinations. Only the UL130 vaccine induced epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies and no synergy was observed from bi- or trivalent combinations. In rabbits the UL130 vaccine again induced epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies while UL128 or UL131 vaccines did not. To evaluate compatibility of the UL130 vaccine with DNA vaccines encoding gB or pp65, mono-, bi-, or trivalent combinations were evaluated. Fibroblast and epithelial entry neutralizing titers did not differ between rabbits immunized with gB alone vs. gB/UL130, gB/pp65, or gB/UL130/pp65 combinations, indicating a lack of antagonism from coadministration of DNA vaccines. Importantly, gB-induced epithelial entry neutralizing titers were substantially higher than activities induced by UL130, and both fibroblast and epithelial entry neutralizing titers induced by gB alone as well as gB/pp65 or gB/UL130/pp65 combinations were comparable to those observed in sera from humans with naturally-acquired CMV infections. These findings support further development of Vaxfectin®-formulated gB-expressing DNA vaccine for prevention of congenital CMV infections.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, vaccine, neutralizing antibody

1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections cause birth defects among newborns infected in utero and morbidity and mortality in transplant and AIDS patients. While the 235-kb CMV genome encodes at least 165 proteins [1], CMV vaccine research has focused on a limited number of viral proteins that dominate cellular or humoral immune responses during natural infection. Early studies revealed that phosphoprotein 65 (pp65) induces cytotoxic T cells while glycoprotein B (gB) is a potent inducer of antibodies. Using fibroblast-based neutralizing assays, over half of the neutralizing activity in sera from naturally infected individuals is specific for epitopes within gB [2-4]. Consequently, a vaccine comprised of a recombinant gB with the MF59 oil and water adjuvant (gB/MF59) was developed and shown to be safe and highly immunogenic in humans [5]. Importantly, vaccination of humans elicited fibroblast entry neutralizing activities comparable to those produced by natural infection [6]. In subsequent phase 2 trials the gB/MF59 vaccine was 50% protective against primary maternal infection [7] and reduced duration of CMV viraemia and requirement for antiviral treatment following solid organ transplantation [8]. Similarly, ASP0113 (previously called TransVax™), a poloxamer-formulated DNA vaccine encoding gB and pp65 [9], significantly decreased occurrence and recurrence of viraemia in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients [10].

That the gB/MF59 vaccine provided only partial protection suggested that inclusion of additional neutralizing targets might yield increased efficacy. Other glycoprotein complexes contain fibroblast entry neutralizing epitopes, including a heterodimer of glycoprotein M and glycoprotein N and a heterotrimer of glycoprotein H (gH), glycoprotein L (gL), and glycoprotein O [11-13]. In addition, a recently described pentameric complex comprised of gH and gL bound to three additional viral proteins, UL128, UL130, and UL131, is necessary for efficient entry into epithelial and endothelial cells, monocytes, and certain dendritic cells [14-20], and antibodies specific for the pentameric complex selectively block viral entry into these cell types but not fibroblasts [12, 21-24]. Following natural infection serum neutralizing titers measured with epithelial cells are significantly higher than those measured using fibroblasts [25-28]. Importantly, while fibroblast entry neutralizing titers induced by the gB/MF59 vaccine are comparable to those induced following natural infection, epithelial entry neutralizing titers were shown to be 15-fold lower, suggesting a significant deficiency of the gB/MF59 vaccine relative to natural humoral immunity [25]. Thus, an effective CMV vaccine may need to elicit robust neutralizing activities against both fibroblast and epithelial cell entry. In the present study gB and the UL128, UL130, and UL131 subunits of the pentameric complex were evaluated as DNA vaccine immunogens.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cells

Human MRC-5 fibroblasts (ATCC CCL-171) and ARPE-19 epithelial cells (ATCC CRL-2302) were obtained from ATCC and propagated in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone Laboratories), 10,000 IU/L penicillin, 10 mg/L streptomycin (Gibco-BRL) (DMEM). HEK-293T cells (a gift from Deborah Parris) were propagated in DMEM as above except that a low glucose formulation was used.

2.2 Viruses

BADrUL131-Y4 (BADr) is a variant of CMV strain AD169 in which a mutation in UL131 has been repaired to express a functional UL131 protein [29]. TS15-rN is a variant of strain Towne in which a mutation in UL130 has been spontaneously repaired during adaptation for growth in epithelial cells to express a functional UL130 protein [30]. ABV is an epithelial-adapted variant of clinical strain Uxc [30](Cui et al., manuscript in preparation). All three viral genomes were cloned as bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones and have been modified to express green fluorescent protein (GFP) [31, 32](Cui et al., manuscript in preparation). Infectious viruses were reconstituted by transfection of BAC DNA into ARPE-19 cells as described [32]. Viruses were amplified in ARPE-19 cultures. Frozen stocks were prepared from ARPE-19 culture supernatants and titered as described previously [32]. Low passage CMV clinical isolates were cultured as described [33]. Uxc and CLS001 were isolated from urines of congenitally infected newborns, while isolates 32691 and 32583 were isolated from urines of children attending daycares in the Richmond or Norfolk VA areas. Isolates were passaged 3-6 times in MRC-5 cells. Frozen stocks were prepared from culture supernatants.

2.3 DNA vaccines

Amino acid sequences for UL128 and UL131 from Towne strain were deduced directly from Towne DNA sequences (GenBank accession GQ121041), whereas the sequence of wild-type Towne UL130 was deduced following removal of a 2-bp insertion in the Towne UL130 gene that is believed to have been acquired during in vitro passage [15]. Codon-optimized open reading frames were synthesized and inserted into DNA vaccine vector VR10551 [9] by Blue Heron Biotechnology, Inc., to produce three plasmids: VR-63128, VR-63130, and VR-63131, encoding UL128, UL130, and UL131, respectively. Vaccine plasmids VR-6365 (encoding gB) and VR-6368 (encoding pp65) have been described elsewhere [9]. Plasmid DNA stocks used for immunization were produced by Puresyn Inc, PA.

Vaxfectin® consists of a 1:1 molar mixture of a cationic lipid GAP-DMORIE and a neutral co-lipid DPyPE. GAP-DMORIE [(±)-N-(3-aminopropyl)-N,N-dimethyl-2,3-bis(cis-9-tetradecenyloxy)-1-propanaminium bromide] was synthesized as previously described [34]. DPyPE (1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3- phosphoethanolamine) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Vaxfectin® formulations were prepared on the day of administration as multiple-vial formulations, as previously described [34]. Vaxfectin® vials containing a dried lipid film were reconstituted with 0.9% sodium chloride; Vaxfectin® liposomes were then added to an equal volume of DNA prepared in another vial at twice the target DNA concentration in 0.9% sodium chloride, 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2 and mixed by gentle inversion.

2.4 Animal immunizations

Animal studies were conducted at Explora Biolabs (San Diego, CA). Animal care and procedures were conducted in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 86–23, 1985) and followed protocols that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Explora Biolabs and Virginia Commonwealth University.

2.4.1. Mouse immunizations

Six week old female BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories) were immunized with three identical doses at three-week intervals. Each dose consisted of 90 μg total DNA formulated with Vaxfectin® delivered as bilateral 50-μL injections into the rectus femoris muscles. Blood samples were obtained prior to administration of each dose from the facial vein using 5 mm Goldenrod lancets. Terminal blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture three weeks after administration of the third dose. Serum was prepared using gold-top gel serum separator tubes (BD) and stored at −20°C.

2.4.2. Rabbit immunizations

Adult New Zealand White female rabbits (Charles River) were immunized with three identical doses at three-week intervals. For the first rabbit study each dose consisted of 1 mg DNA formulated with Vaxfectin® delivered as bilateral 500-μL injections into the vastus lateralis muscles. Blood samples were obtained prior to administration of each dose and terminal blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture 21 days after administration of the third dose. For the second study each monovalent vaccine dose consisted of 0.5 mg DNA formulated with Vaxfectin® delivered as a single unilateral 750-μL injection into alternate vastus lateralis muscles; each bivalent vaccine dose consisted of 0.5 mg of each DNA (1.0 mg total) formulated with Vaxfectin® delivered as bilateral 750-μL injections into both vastus lateralis muscles; each trivalent vaccine dose consisted of 0.5 mg of each DNA (1.5 mg total) formulated with Vaxfectin® delivered as bilateral 750-μL injections into both vastus lateralis muscles. Blood samples were obtained prior to administration of each dose and terminal blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture 44 days after administration of the third dose.

2.5 Neutralizing antibody assays

2.5.1 GFP-based neutralizing assays

GFP-based assays were conducted as described previously [21, 25, 35]. For initial screenings sera were diluted 1:10 in cell culture media, incubated with an equal volume of DMEM containing 5000 PFU of the indicated GFP-tagged virus for 1 h at 37°C, then transferred in triplicate to wells of black-walled, clear-bottom 384-well plates containing confluent ARPE-19 or MRC-5 cells. For titer determination sera were first diluted 1:10 and then two-fold serially diluted in cell culture medium. Each dilution was then incubated with virus and added to wells containing confluent ARPE-19 or MRC-5 cells as above. In some experiments sera were heat inactivated for 30 min. at 56°C before serial dilution, then mixed with virus diluted in cell culture medium containing 10% rabbit complement (Sigma Aldrich). Representative images were taken four or five days post infection using a Nikon Diaphoto 300 microscope. Relative fluorescent units (RLU) of GFP were measured for each well using a Biotek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader seven days after infection. Mean RLUs (from triplicate wells) were plotted vs. log (serum dilution−1) and best fit four-parameter curves were determined using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Neutralizing titers were reported as inverse serum dilutions corresponding to 50% reductions in GFP levels per well.

2.5.2. Neutralizing assays using low passage clinical isolates

Sera were heat inactivated 30 min. at 56°C, serially diluted, and mixed with an equal volume of each virus stock diluted in cell culture medium containing 10% rabbit complement. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, reactions were transferred to wells of clear 96-well plates containing confluent ARPE-19 or MRC-5 cells. Foci of immediate early (IE) antigen-positive cells were detected by the method of Abai et al. [36] 5 days post infection of MRC-5 cultures or 10 days post infection of ARPE-19 cultures. The amounts of each virus stock used in neutralizing assays were predetermined to result in 10-20 foci per well by titration on MRC-5 or ARPE-19 cultures and staining for IE antigen-positive cells as described above. Numbers of IE-antigen positive foci were plotted vs. log (serum dilution−1) and best fit four-parameter curves were determined using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Neutralizing titers were reported as inverse serum dilutions corresponding to 50% reductions in the number of IE antigen-positive foci per well.

2.6 Expression and purification of recombinant Nus-UL130

Sequences encoding amino acids 32-126 of UL130 were cloned into expression vector pET43-1b to produce a 6xhis- and S-tagged fusion protein consisting of N-terminal E. coli Nus protein fused to UL130 sequences. The Nus-UL130 protein was expressed and purified under native conditions using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography followed by S-tag agarose chromatography. Nus protein lacking C-terminal UL130 sequences was expressed and purified in parallel.

2.7 Measuring gB- and UL130- antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA titers of gB-reactive antibodies were determined as described previously [37]. Briefly, 96-well Imobilon I ELISA plates (Fisher Scientific) were coated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/well recombinant gB purified from stably transfected CHO cells (a gift to Stuart Adler from Sanofi-Aventis, Lyon, France) in sodium carbonate buffer pH 9.4. Wells were washed four times with wash buffer (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, pH 7.4), then blocked with blocking buffer (wash buffer with 3% bovine serum albumin) for one hour at room temperature. Test sera were diluted 1:100, 1:400, 1:1,600, 1:6,400, or 1:25,600 in blocking buffer and incubated in wells for one hour at room temperature. Wells were washed four times with wash buffer and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo) diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer. Wells were washed four times with wash buffer and incubated with TMB substrate solution (Sigma) for approximately 30 min until the desired color intensity was reached. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of 2N HCl and optical density (O.D.) values were read at A450 nm using a Biotek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. Mean O.D.s (from duplicate wells) were plotted vs. log (serum dilution−1) and fitted to four-parameter curves using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Titers were interpolated from fitted curves as inverse serum dilutions corresponding to an O.D. of 0.1.

ELISA titers of UL130-reactive antibodies were determined as above except that alternate rows were coated with either 60 ng/well of Nus-UL130 or Nus control protein. Titers were determined as above using delta O.D. values calculated as O.D. (Nus-UL130) – O.D. (Nus) for each serum/dilution.

2.8 Western blotting

HEK-293T cells were transfected with vaccine plasmids or GFP expression plasmid pMA178b as previously described [35]. Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to membranes using standard Western blot methods [19]. Membranes were probed for UL128, UL130, or UL131 using rabbit antisera specific to UL128, UL130, or UL131 [19] (gifts from David Johnson) as previously described [35]. To detect IgG reactive to UL128, UL130, or UL131 in sera from DNA-vaccinated mice, lysates of HEK-293T cells that had been transfected with vaccine plasmids (above) were used as Western blot antigens. Blots were developed using HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Thermo) diluted 1:5000. To detect IgG reactive to UL130 in sera from UL130 DNA-vaccinated rabbits E. coli-expressed purified Nus-UL130 or Nus control proteins were used as Western blot antigens (1 μg/lane). Blots were developed using HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo) diluted 1:8333.

2.9 Human Sera and CytoGam®

CytoGam® was purchased from the manufacturer (CSL Behring, King of Prussia, PA). The 50 mg/ml stock was adjusted to 10 mg/ml with culture medium to approximate the concentration of IgG in human sera. Human sera were obtained from normal healthy adults and assayed for CMV seropositivity by gB-ELISA. Research conducted with human sera was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Committee for the Conduct of Human Research.

3. Results

3.1 Evaluation of DNA vaccines encoding UL128, UL130, and UL131 in vitro and in vivo

DNA vaccines encoding full-length, native UL128, UL130, or UL131 proteins derived from Towne strain were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. HEK 293T cells were transfected with each DNA and cell lysates were assayed by Western blotting using specific antisera. In each case the antisera reacted with an appropriate-sized protein only in lysates of cells transfected with the DNA encoding the corresponding protein (Fig. 1). Thus, each DNA vaccine expresses the relevant encoded protein in vitro.

Figure 1. DNA vaccines express CMV proteins in vitro.

HEK293 cells were mock transfected or transfected with DNA vaccines encoding UL128, UL130, or UL131, or with a GFP-encoding control plasmid, as indicated above each lane. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with rabbit anti-peptide antisera specific for UL128, UL130, or UL131. The locations of molecular weight standards are indicated.

To assess immunogenicity in vivo, groups of 10 mice were immunized with monovalent DNA vaccines, pairwise bivalent combinations, or the trivalent combination of all three. Mice received intramuscular injections of 90 μg total DNA formulated with Vaxfectin® on days 0, 21, and 42, and blood samples were obtained on day 62. Vaxfectin® is a cationic lipid-based adjuvant that has been shown to significantly enhance antibody responses to several different antigens encoded by DNA vaccines compared to DNA vaccines administered without Vaxfectin® [34, 38]. Sera obtained on day 62 were assayed by Western blot for reactivities to UL128, UL130, or UL131. Of the 40 mice that received UL130 DNA as a mono-, bi-, or trivalent vaccine, 21 had UL130-reactive antibodies. Of the ten mice that received monovalent UL130 DNA, eight developed antibodies reactive to UL130 (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). In contrast, of the 39 mice that received immunizations containing UL128 or UL131 DNAs, only one mouse in each group developed antibodies to the respective immunogens (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibody responses of mice immunized with DNA vaccines

| Vaccine(s) | number immunized |

number Western blot reactive (antigen) |

number with epithelial entry neutralizing activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| UL128 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| UL130 | 10 | 8 | 2c |

| UL131 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| UL128+UL130 | 10 | 1 (UL130) | 0 |

| UL128+UL131 | 9a | n.d.b | 0 |

| UL130+UL131 | 10 | 6 (UL130) 1 (UL131) |

0 |

| UL128+UL130+UL131 | 10 | 6 (UL130) | 0 |

one animal in this group died before the study was completed

not determined

epithelial entry neutralizing titers for these two animals were 214 and 154

Figure 2. Immunogenicity of monovalent UL130 DNA vaccine in mice.

(A) HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-encoding control plasmid DNA or UL130 vaccine DNA as indicated above each lane. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with day-62 sera from ten mice (2-1 through 2-10) that were immunized with the UL130 DNA vaccine. As a control a replicate blot was probed with rabbit antisera to UL130 peptide (α-130). (B) Representative images from epithelial entry neutralizing assays conducted on day-62 sera from mice 2-4 and 2-8. Serum dilutions are indicated above; neutralizing titers for each serum determined from GFP measurements are shown to the right.

Day-62 sera were next tested for epithelial entry neutralizing activity against virus BADr. Two mice exhibited epithelial entry neutralizing activity above background with titers of 154 and 214 (Fig. 2B). Both had received the monovalent UL130 DNA vaccine and had reactivity to UL130 by Western blot (Fig. 2A). Day 62 sera from mice from all other groups lacked detectable epithelial entry neutralizing activity at a 1:10 dilution (Table 1).

3.2 Antibody responses in rabbits immunized with monovalent DNA vaccines

Monovalent DNA vaccines encoding UL128, UL130, or UL131 were next administered to groups of five rabbits. Each rabbit received three doses of 1 mg DNA formulated with Vaxfectin® on days 0, 21, and 42. Sera obtained on day 64 from UL128- or UL131-immunized rabbits had no epithelial entry neutralizing activity, while sera from all five UL130-immunized animals exhibited epithelial entry neutralizing activities at a 1:10 dilution (Fig. 3A). These sera also exhibited Western blot reactivity to an E. coli-expressed UL130 fusion protein (Fig. 3B). Titers for the five day-64 sera from UL130-immunized rabbits were determined using three viral strain backgrounds. Titers were lower than those of a human seropositive serum that was included for comparison (Table 2).

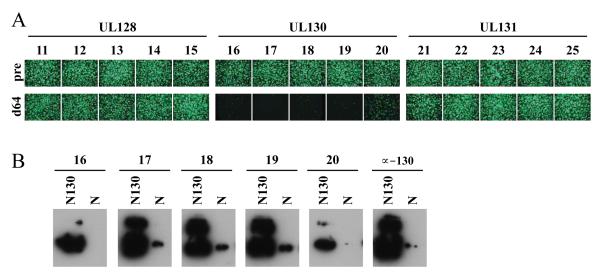

Figure 3. Immunogenicity of monovalent UL128, UL130, and UL131 DNA vaccines in rabbits.

(A) Groups of five rabbits were immunized with monovalent UL128, UL130, or UL131 vaccines as indicated. Micrographs show representative epithelial entry neutralizing results for preimmune (pre) or day-64 postimmune (d64) sera assayed at a 1:10 dilution using virus BADr. (B) Recombinant Nus-UL130 (N130) or Nus (N) control proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with day-64 sera from five rabbits (16 through 20) that were immunized with the UL130 DNA vaccine. As a control a replicate blot was probed with rabbit antisera to UL130 peptide (α-130).

Table 2.

Epithelial entry neutralizing titersa of day-64 sera from rabbits immunized with the UL130 DNA vaccine determined using three different CMV strain backgrounds

| sample | virus (strain background) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ABV (Uxc) |

BADr (AD169) |

TS15-rN (Towne) |

|

| rabbit 16 | 3 | 74 | 44 |

| rabbit 17 | 311 | 374 | 517 |

| rabbit 18 | 76 | 188 | 92 |

| rabbit 19 | 131 | 264 | 345 |

| rabbit 20 | 4 | 17 | 16 |

|

| |||

| geometric mean titer | 33 | 118 | 103 |

|

| |||

| human serumb | 2077 | 2514 | 1863 |

inverse serum dilutions resulting in 50% reductions in GFP

serum from a naturally infected human subject

3.3 Antibody responses in rabbits immunized with DNA vaccines encoding UL130, gB, and pp65

Groups of six rabbits were next immunized with monovalent DNA vaccines expressing UL130 or gB, bivalent combinations of plasmids expressing UL130+gB or gB+pp65, or the trivalent combination of plasmids expressing UL130+gB+pp65. A three-dose immunization schedule similar to that described in section 3.2 was used, except that (i) the dose of each plasmid (0.5 mg) was half that used in the previous study, and (ii) final sera were obtained on day 87, 44 days after the third vaccine dose.

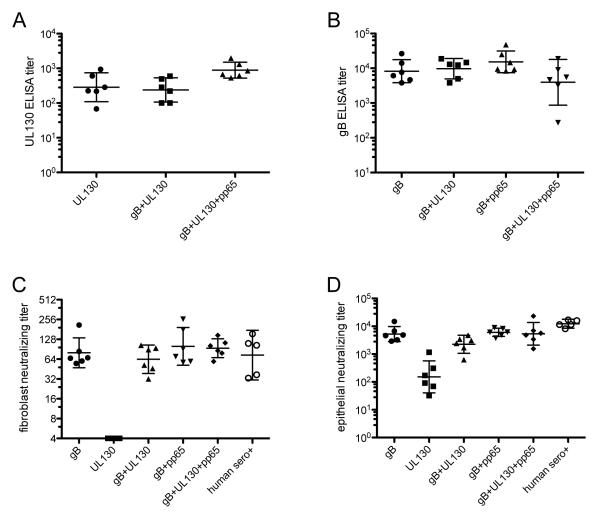

Rabbit sera were assayed by ELISA for UL130- or gB-specific IgG. Preimmune sera diluted 1:100 (the highest concentration tested) lacked reactivity in both assays (data not shown). UL130 ELISA results for day 87 sera revealed that all animals immunized with a vaccine that included the UL130-expressing plasmid developed UL130-reactive antibodies. Inclusion of additional plasmids encoding gB or pp65 did not reduce mean antibody responses to UL130 (Fig. 4A). Results of gB ELISAs were similar. All animals immunized with a vaccine that included the gB-expressing plasmid developed gB-reactive antibodies and inclusion of additional plasmids encoding UL130 and/or pp65 did not reduce mean antibody responses to gB (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Immunogenicity of UL130, gB, and pp65 DNA vaccines alone and in combination.

Groups of six rabbits were immunized with gB, UL130, or pp65 DNA vaccines separately or in the indicated combinations. Rabbit sera obtained on day 87 (44 days after the third vaccine dose) were assayed by ELISA to determine IgG titers specific for UL130 (A) or gB (B). The same day-87 rabbit sera and five seropositive (sero+) human sera were assayed for neutralizing activity against entry of virus BADr into MRC-5 fibroblasts (C) or ARPE-19 epithelial cells (D). Lines indicate geometric means bracketed by 95% confidence intervals.

Rabbit sera and five human seropositive sera were assayed simultaneously for fibroblast and epithelial entry neutralizing activities using virus BADr. Preimmune sera lacked neutralizing activities at a 1:10 dilution (data not shown). As expected, the monovalent UL130 vaccine did not induce fibroblast entry neutralizing activities, but fibroblast entry neutralizing activities were observed in all animals that received vaccines that contained the gB-expressing plasmid (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the gB ELISA data above, inclusion of plasmids encoding UL130 or pp65 did not reduce fibroblast entry neutralizing titers. Importantly, fibroblast neutralizing titers for all rabbits immunized with vaccines containing the gB plasmid were comparable to those of the naturally infected human subjects (Fig. 4C).

Epithelial entry neutralizing activities were observed in day 87 sera from all rabbits (Fig. 4D). Despite the lower DNA dose and different time point sampled, monovalent UL130 induced epithelial entry neutralizing titers that were comparable to those from the previous study. However, the GMT for rabbits immunized with monovalent UL130 was 81-fold lower than the GMT for the five naturally infected human subjects. In contrast, monovalent gB immunization induced epithelial entry neutralizing activities that were on average 35-fold higher than those induced by UL130 immunization. No significant increase was achieved by combining gB- and UL130-expressing plasmids, but conversely, coadministering gB with pp65 and/or UL130 did not negatively impact epithelial entry neutralizing titers (Fig. 4D). Importantly, all animals that received a vaccine containing the gB-expressing plasmid had relatively high epithelial entry neutralizing titers. Geometric mean titers for vaccine groups that included the gB plasmid DNA were 2.0- to 5.5-fold lower than the geometric mean titer of the five human sera.

3.4 Complement dependence of antibodies to gB induced by DNA vaccination

To determine the complement dependence of gB-specific antibodies induced by the gB-expressing DNA vaccine, sera from the six rabbits immunized with gB plasmid alone (shown in Fig. 4) were heat inactivated and then assayed for neutralizing activity in the presence or absence of added rabbit complement. Complement dramatically increased the neutralizing potency of gB-specific antibodies induced by the gB DNA vaccine; geometric mean titers for epithelial entry neutralizing activity increased 24-fold, while fibroblast entry neutralizing titers increased 100-fold (Fig. 5). In contrast, complement increased the fibroblast entry neutralizing activity of CytoGam® only 2.6-fold while epithelial entry neutralizing activity was unaffected. Consequently, in the presence of complement, neutralizing titers for sera from gB-vaccinated rabbits were comparable to or higher than titers for CytoGam®, which in this experiment was first adjusted to 10 mg/ml to approximate the concentration of IgG in human serum (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Complement dependence of antibodies induced by gB DNA vaccination.

Sera from six rabbits that were immunized with gB DNA (Fig. 4) were heat inactivated, then assayed for neutralizing activity against entry of virus BADr into MRC-5 fibroblasts or ARPE-19 epithelial cells in the absence (C−) or presence (C+) of 5% rabbit complement. CytoGam® was assayed in parallel after dilution to 10 mg/ml to approximate the IgG concentration in human serum.

3.5 Antibodies to gB induced by DNA vaccination neutralize CMV clinical isolates

To determine if antibodies induced by the gB-expressing DNA vaccine can neutralize low passage clinical strains of CMV, four independent clinical isolates were passaged 3-6 times on MRC-5 cells, then culture supernatants were used for neutralizing assays in which virus entry was determined by staining cells for expression of CMV IE antigens. Sera from the six rabbits immunized with gB plasmid neutralized fibroblast entry of all four clinical strains. For three of the four strains fibroblast entry neutralizing titers were higher than those of CytoGam® adjusted to 10 mg/ml, while for one strain (32583) titers were slightly (2.5-fold) below CytoGam® (Fig. 6). Epithelial entry neutralizing titers could only be determined using strain Uxc, as stocks of the other three clinical strains lacked epithelial tropism. All six rabbit sera potently neutralized Uxc entry into epithelial cells with titers comparable to CytoGam® adjusted to 10 mg/ml (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Antibodies to gB induced by DNA vaccination neutralize CMV clinical isolates.

Sera from six rabbits that were immunized with gB DNA (Fig. 4) were heat inactivated and assayed in the presence of 5% rabbit complement for neutralizing activity against entry of low passage CMV clinical isolates 32691, 32583, CLS001, or Uxc into fibroblasts (MRC-5) or epithelial cells (ARPE-19). Virus entry was determined by staining cells for expression of CMV IE antigens. CytoGam® was assayed in parallel after dilution to 10 mg/ml to approximate the IgG concentration in human serum.

4. Discussion

Development of gB-based vaccines was motivated by the discovery that antibodies to gB comprise the majority of the fibroblast-specific neutralizing activity induced by natural infection [2-4]. At that time it was not suspected that CMV entry into different cell types might utilize different entry mediators or that fibroblast-based assays might fail to detect certain cell type-specific neutralizing activities. Thus, induction of fibroblast entry neutralizing responses comparable to natural infection was considered an important attribute of the gB/MF59 vaccine [6]. That this vaccine reduced the incidence of primary maternal infection by 50% [7] was a landmark observation: for the first time, a vaccine primarily designed to induce neutralizing antibodies was shown to be protective against CMV.

While the gB/MF59 vaccine trial [7] was ongoing a novel endocytic pathway was described for CMV entry into epithelial and endothelial cells, monocytes, and certain dendritic cells [14-20]. Compared to entry into fibroblasts, entry into cells requiring the endocytic pathway is substantially more sensitive to neutralization by seropositive human sera [25-28]. This is due to the presence of pentamer-specific antibodies that potently block endocytic entry but have no effect on fibroblast entry [12, 22-24]. In this regard the gB/MF59 vaccine is clearly deficient – inducing epithelial-specific neutralizing titers fifteen-fold lower than those induced by natural infection [25]. Given that the types of cells that CMV infects via the endocytic pathway play important roles in viral transmission, replication, dissemination, and pathogenesis in vivo, induction of potent neutralizing activities against both fibroblast and endocytic entry is likely to be important for vaccine efficacy. How this can be achieved is a current challenge for CMV vaccine development.

The minimal complexity of pentamer-based immunogens necessary to induce potent neutralizing responses is not certain. At one end of the complexity spectrum, two short synthetic peptides, one from UL130 and the other from UL131, contain epitopes capable of inducing potent epithelial entry neutralizing responses in rabbits [21]. Sera raised against the individual UL128, UL130, and UL131 subunits also have epithelial-specific neutralizing activity [17, 18, 26]. That highly potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies recognize epitopes that require co-expression of two or more pentamer subunits indicates that the pentamer also contains potent neutralizing epitopes that are conformational and dependent on quaternary structure [12]. However, many of these epitopes require co-expression of two or all three of the UL128, UL130, and UL131 subunits [12]. This suggests that UL128, UL130, and UL131 can interact to form quaternary neutralizing epitopes, and therefore, there is potential for synergy from vaccination with bi or trivalent combinations of the UL128, UL130, and UL131 subunits.

To characterize the immunogenicity of pentamer subunits, three DNA vaccines encoding individual subunits were constructed. Consistent with results recently reported by Fu et al. [39], only UL130 elicited epithelial entry neutralizing responses following DNA vaccination of mice. We extended these findings by examining bi and trivalent combinations, but no synergy was observed from immunizing with any subunit combination. Thus, neutralizing epitopes that rely on interactions between two or more subunits are either not immunogenic in mice or cannot be adequately represented following expression by the vaccines tested. Support for the latter possibility is suggested by the absence of any detectable serological reactivity, even to denatured determinants, as measured by Western blot with serum from the majority of UL128- and UL131-vaccinated mice (Table 1). In addition, it may be that in vivo the frequency of cells co-expressing two or three proteins encoded on unlinked DNAs is relatively low. If so, vaccines in which multiple subunits are expressed from a single vector might be more effective in presenting multi-subunit epitopes. Indeed, a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)-vectored vaccine that expresses all five pentamer subunits was recently shown to induce potent epithelial and fibroblast neutralizing responses [40].

Results for monovalent vaccines in rabbits were comparable to those in mice in that only the UL130 vaccine induced neutralizing antibodies. Responses in rabbits were generally more consistent than in mice - while only two out of ten UL130-immunized mice exhibited neutralizing activities, all eleven UL130-immunized rabbits developed neutralizing responses and seven had titers > 100.

Sera from five UL130-immunized rabbits were tested for neutralizing activity against three different CMV strain backgrounds. While titers against the AD169 and Towne background viruses were similar, titers against the Uxc strain were ~3-fold lower (Table 2). That titers of human sera, which also target epitopes outside of UL130, did not differ significantly between strains indicates that low titers are not a consistent feature of assays conducted with the Uxc strain or this particular virus stock. These results suggest that the UL130 DNA vaccine, which encodes UL130 from Towne strain, may provide reduced neutralization of other CMV strains. Of note, the UL130 encoded by Uxc contains a polymorphism (P40L) within the region identified as containing a potent neutralizing epitope [21], while Towne and AD169 UL130 sequences are identical within this region. Thus, if this epitope dominates the neutralizing response induced by the UL130 DNA vaccine, reduced neutralization of Uxc strain by antibodies raised against Towne UL130 may be attributable to this single polymorphism.

To assess the compatibility of the UL130 vaccine with DNA vaccines encoding gB and pp65, mono-, bi-, and trivalent combinations were tested. Epithelial entry neutralizing responses to the monovalent gB vaccine were on average 35-fold higher than those induced by UL130. When gB was combined with pp65, UL130, or both, no evidence was observed for antagonism with respect to either gB- or UL130-specific antibodies or fibroblast or epithelial entry neutralizing titers. However, combining UL130 and gB vaccines also produced no enhancement of epithelial entry neutralizing titers over those induced by gB alone. Thus, monovalent (gB), bivalent (gB+pp65), or trivalent (gB+pp65+UL130) vaccines were equally immunogenic with respect to neutralizing responses (Fig. 4C and 4D).

Because natural maternal infection reduces the incidence and severity of congenital CMV infections, immune responses induced by natural infection are considered an important benchmark for vaccine development. Importantly, both fibroblast and epithelial entry neutralizing titers induced by gB in the context of Vaxfectin®-formulated DNA vaccines compared favorably to those of five naturally infected human subjects, or to CytoGam® (a mixture of IgG purified from human CMV seropositive blood donors) after adjustment to a concentration matching normal IgG levels in human sera. Fibroblast entry neutralizing titers for rabbit vaccine groups were within or above the human sera range, while epithelial entry neutralizing titers overlapped the human sera range and were, on average, within 2.0- to 5.5-fold of the human sera. In contrast to CytoGam®, rabbit antibodies induced by the gB DNA vaccine were highly complement dependent. When assayed in the presence of added complement, sera from rabbits immunized with Vaxfectin®-formulated gB DNA effectively neutralized four independent low passage CMV clinical isolates and exhibited potencies that were comparable or superior to those of CytoGam®.

It is important to note that human sera represent a mixture of antibody reactivities: gB, gH/gL/gO, and/or gM/gN may contribute to fibroblast neutralizing specificities while gB, gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131, and gM/gN may contribute to epithelial cell neutralizing activities [2-4, 11-13, 22-24]. In this context, immunization with only a gB-expressing plasmid DNA vaccine, in the absence of any other viral entry mediators, induced appreciable levels of neutralizing antibodies capable of blocking both fibroblast and epithelial cell entry (Figs. 4-6). It is likely that the use of Vaxfectin® contributed to these antibody titers since this adjuvant formulation has previously been shown to augment antibody titers to a variety of immunogens encoded by plasmid DNA vaccines when compared to the same vaccines administered without Vaxfectin® or with alternative formulations or delivery methods [34, 38, 41].

Taken together, these results indicate that antibodies induced by a Vaxfectin®-formulated gB DNA vaccine are capable of producing in rabbits robust fibroblast and epithelial entry neutralizing activities that are comparable to those induced by CMV infection of humans. Moreover, the gB-expressing plasmid appears to be compatible with plasmids expressing other immunogens, including pp65, which may be desirable in a congenital CMV vaccine.

In recent years encouraging fibroblast- and epithelial-specific neutralizing results have been reported for a variety of novel vaccine strategies, including CMV virions or dense bodies, gB-containing virus-like particles, alphavirus replicon particles or MVA expressing gH/gL or pentameric complex, and recombinant gH/gL or pentameric complex [28, 39, 40, 42-45]. Results from these studies confirm the potential of pentamer-based immunogens for inclusion in a CMV vaccine and are consistent with evidence that in response to natural infection the pentamer dominates while gB plays a minor role in inducing epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies [22, 24, 25]. However, results presented here and in other studies [42, 45] indicate that when optimally presented, gB has the capacity to induce potent neutralizing responses against both fibroblast and epithelial cell entry. The rabbit studies presented here suggest that a Vaxfectin®-formulated gB DNA vaccine administered to humans may achieve neutralizing responses similar to those induced by natural infection. Given the simplicity afforded by this single-subunit immunogen, further development of gB-based vaccines is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01AI088750 and R21AI073615 (to M.A.M) from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Dai Wang and Thomas Shenk for BAC clone BADrUL131-Y4 and David Johnson for rabbit antisera to UL128, UL130, and UL131.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Dolan A, Cunningham C, Hector RD, Hassan-Walker AF, Lee L, Addison C, et al. Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1301–12. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Marshall GS, Rabalais GP, Stout GG, Waldeyer SL. Antibodies to recombinant-derived glycoprotein B after natural human cytomegalovirus infection correlate with neutralizing activity. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:381–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gonczol E, deTaisne C, Hirka G, Berencsi K, Lin WC, Paoletti E, et al. High expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-gB protein in cells infected with a vaccinia-gB recombinant: the importance of the gB protein in HCMV immunity. Vaccine. 1991;9:631–7. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90187-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Britt WJ, Vugler L, Butfiloski EJ, Stephens EB. Cell surface expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gp55-116 (gB): use of HCMV-recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in analysis of the human neutralizing antibody response. J Virol. 1990;64:1079–85. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1079-1085.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Frey SE, Harrison C, Pass RF, Yang E, Boken D, Sekulovich RE, et al. Effects of antigen dose and immunization regimens on antibody responses to a cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1700–3. doi: 10.1086/315060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pass RF, Duliege AM, Boppana S, Sekulovich R, Percell S, Britt W, et al. A subunit cytomegalovirus vaccine based on recombinant envelope glycoprotein B and a new adjuvant. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:970–5. doi: 10.1086/315022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pass RF, Zhang C, Evans A, Simpson T, Andrews W, Huang ML, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1191–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Griffiths PD, Stanton A, McCarrell E, Smith C, Osman M, Harber M, et al. Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant in transplant recipients: a phase 2 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1256–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Selinsky C, Luke C, Wloch M, Geall A, Hermanson G, Kaslow D, et al. A DNA-based vaccine for the prevention of human cytomegalovirus-associated diseases. Hum Vaccin. 2005;1:16–23. doi: 10.4161/hv.1.1.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Boeckh M, Wilck MB, Langston AA, Chu AH, Wloch MK, et al. A novel therapeutic cytomegalovirus DNA vaccine in allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:290–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Urban M, Klein M, Britt WJ, Hassfurther E, Mach M. Glycoprotein H of human cytomegalovirus is a major antigen for the neutralizing humoral immune response. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 7):1537–47. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Macagno A, Bernasconi NL, Vanzetta F, Dander E, Sarasini A, Revello MG, et al. Isolation of human monoclonal antibodies that potently neutralize human cytomegalovirus infection by targeting different epitopes on the gH/gL/UL128-131A complex. J Virol. 2010;84:1005–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shimamura M, Mach M, Britt WJ. Human cytomegalovirus infection elicits a glycoprotein M (gM)/gN-specific virus-neutralizing antibody response. J Virol. 2006;80:4591–600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4591-4600.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lauron EJ, Yu D, Fehr AR, Hertel L. Human cytomegalovirus infection of langerhans-type dendritic cells does not require the presence of the gH/gL/UL128-131A complex and is blocked after nuclear deposition of viral genomes in immature cells. J Virol. 2014;88:403–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03062-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hahn G, Revello MG, Patrone M, Percivalle E, Campanini G, Sarasini A, et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J Virol. 2004;78:10023–33. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.10023-10033.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gerna G, Percivalle E, Lilleri D, Lozza L, Fornara C, Hahn G, et al. Dendritic-cell infection by human cytomegalovirus is restricted to strains carrying functional UL131-128 genes and mediates efficient viral antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:275–84. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18153–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Adler B, Scrivano L, Ruzcics Z, Rupp B, Sinzger C, Koszinowski U. Role of human cytomegalovirus UL131A in cell type-specific virus entry and release. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2451–60. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ryckman BJ, Rainish BL, Chase MC, Borton JA, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, et al. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J Virol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Straschewski S, Patrone M, Walther P, Gallina A, Mertens T, Frascaroli G. Protein pUL128 of human cytomegalovirus is necessary for monocyte infection and blocking of migration. J Virol. 2011;85:5150–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02100-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saccoccio FM, Sauer AL, Cui X, Armstrong AE, Habib el SE, Johnson DC, et al. Peptides from cytomegalovirus UL130 and UL131 proteins induce high titer antibodies that block viral entry into mucosal epithelial cells. Vaccine. 2011;29:2705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fouts AE, Chan P, Stephan JP, Vandlen R, Feierbach B. Antibodies against the gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131 complex comprise the majority of the anti-cytomegalovirus (anti-CMV) neutralizing antibody response in CMV hyperimmune globulin. J Virol. 2012;86:7444–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00467-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Freed DC, Tang Q, Tang A, Li F, He X, Huang Z, et al. Pentameric complex of viral glycoprotein H is the primary target for potent neutralization by a human cytomegalovirus vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4997–5005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316517110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lilleri D, Kabanova A, Revello MG, Percivalle E, Sarasini A, Genini E, et al. Fetal human cytomegalovirus transmission correlates with delayed maternal antibodies to gH/gL/pUL128-130-131 complex during primary infection. PloS one. 2013;8:e59863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cui X, Meza BP, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Cytomegalovirus vaccines fail to induce epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies comparable to natural infection. Vaccine. 2008;26:5760–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gerna G, Sarasini A, Patrone M, Percivalle E, Fiorina L, Campanini G, et al. Human cytomegalovirus serum neutralizing antibodies block virus infection of endothelial/epithelial cells, but not fibroblasts, early during primary infection. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:853–65. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tang A, Li F, Freed DC, Finnefrock AC, Casimiro DR, Wang D, et al. A novel high-throughput neutralization assay for supporting clinical evaluations of human cytomegalovirus vaccines. Vaccine. 2011;29:8350–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang D, Li F, Freed DC, Finnefrock AC, Tang A, Grimes SN, et al. Quantitative analysis of neutralizing antibody response to human cytomegalovirus in natural infection. Vaccine. 2011;29:9075–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus UL131 open reading frame is required for epithelial cell tropism. J Virol. 2005;79:10330–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10330-10338.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cui X, Lee R, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Antibody inhibition of human cytomegalovirus spread in epithelial cell cultures. J Virol Methods. 2013;192:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang D, Bresnahan W, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus encodes a highly specific RANTES decoy receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16642–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407233101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cui X, Adler SP, Davison AJ, Smith L, Habib el SE, McVoy MA. Bacterial artificial chromosome clones of viruses comprising the towne cytomegalovirus vaccine. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2012;2012:428498. doi: 10.1155/2012/428498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Adler SP. Molecular epidemiology of cytomegalovirus: viral transmission among children attending a day care center, their parents, and caretakers. J Pediatr. 1988;112:366–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hartikka J, Bozoukova V, Ferrari M, Sukhu L, Enas J, Sawdey M, et al. Vaxfectin enhances the humoral immune response to plasmid DNA-encoded antigens. Vaccine. 2001;19:1911–23. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Saccoccio FM, Gallagher MK, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Neutralizing activity of saliva against cytomegalovirus. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1536–42. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05128-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Abai AM, Smith LR, Wloch MK. Novel microneutralization assay for HCMV using automated data collection and analysis. J Immunol Methods. 2007;322:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jacobson MA, Adler SP, Sinclair E, Black D, Smith A, Chu A, et al. A CMV DNA vaccine primes for memory immune responses to live-attenuated CMV (Towne strain) Vaccine. 2009;27:1540–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Reyes L, Hartikka J, Bozoukova V, Sukhu L, Nishioka W, Singh G, et al. Vaxfectin enhances antigen specific antibody titers and maintains Th1 type immune responses to plasmid DNA immunization. Vaccine. 2001;19:3778–86. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fu TM, Wang D, Freed DC, Tang A, Li F, He X, et al. Restoration of viral epithelial tropism improves immunogenicity in rabbits and rhesus macaques for a whole virion vaccine of human cytomegalovirus. Vaccine. 2012;30:7469–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wussow F, Chiuppesi F, Martinez J, Campo J, Johnson E, Flechsig C, et al. Human cytomegalovirus vaccine based on the envelope gH/gL pentamer complex. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004524. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hartikka J, Bozoukova V, Morrow J, Rusalov D, Shlapobersky M, Wei Q, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the immunogenicity and safety of plasmid DNA-based prophylactic vaccines for human cytomegalovirus. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2012;8:1595–606. doi: 10.4161/hv.21225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kirchmeier M, Fluckiger AC, Soare C, Bozic J, Ontsouka B, Ahmed T, et al. Enveloped virus-like particle expression of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B antigen induces antibodies with potent and broad neutralizing activity. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21:174–80. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00662-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cayatte C, Schneider-Ohrum K, Wang Z, Irrinki A, Nguyen N, Lu J, et al. Cytomegalovirus vaccine strain towne-derived dense bodies induce broad cellular immune responses and neutralizing antibodies that prevent infection of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J Virol. 2013;87:11107–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01554-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wen Y, Monroe J, Linton C, Archer J, Beard CW, Barnett SW, et al. Human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131A complex elicits potently neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2014;32:3796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Loomis RJ, Lilja AE, Monroe J, Balabanis KA, Brito LA, Palladino G, et al. Vectored co-delivery of human cytomegalovirus gH and gL proteins elicits potent complement-independent neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine. 2013;31:919–26. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]