Abstract

The specificity of RNA-guided nucleases has gathered considerable interest as they become broadly applied to basic research and therapeutic development. Reports of the simple generation of animal models and genome engineering of cells raised questions about targeting precision. Conflicting early reports led the field to believe that CRISPR/Cas9 system was promiscuous, leading to a variety of strategies for improving specificity and increasingly sensitive methods to detect off-target events. However, other studies have suggested that CRISPR/Cas9 is a highly specific genome-editing tool. This review will focus on deciphering and interpreting these seemingly opposing claims.

First generation methods to detect potential off-target sites: Computational prediction and in vitro screens

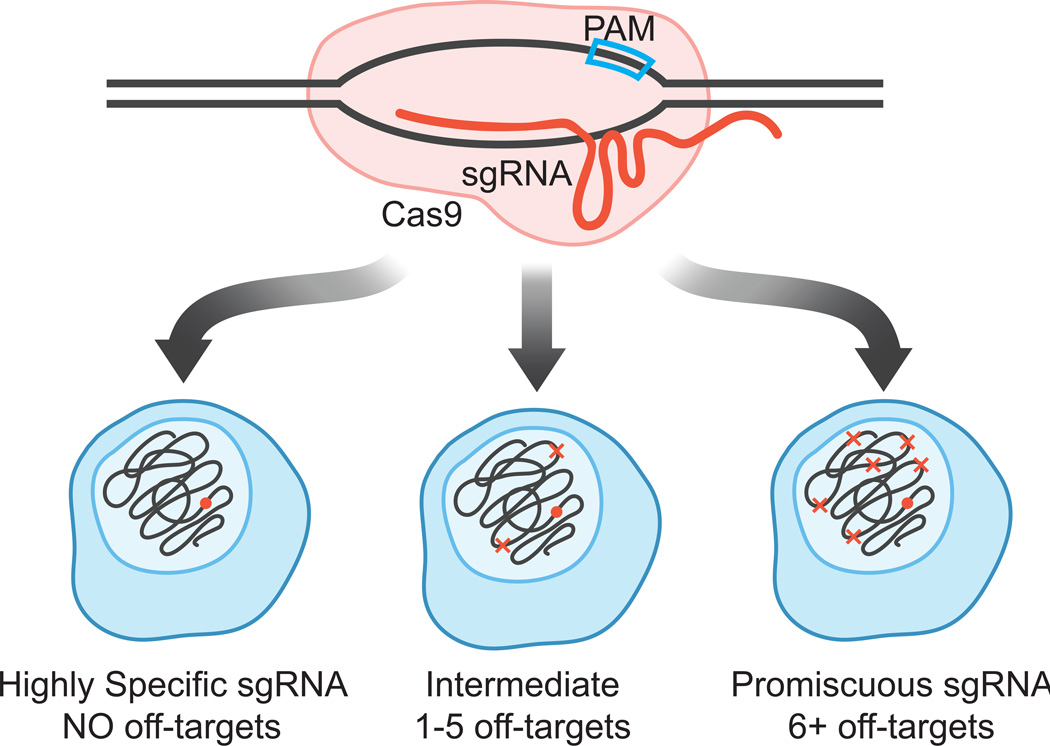

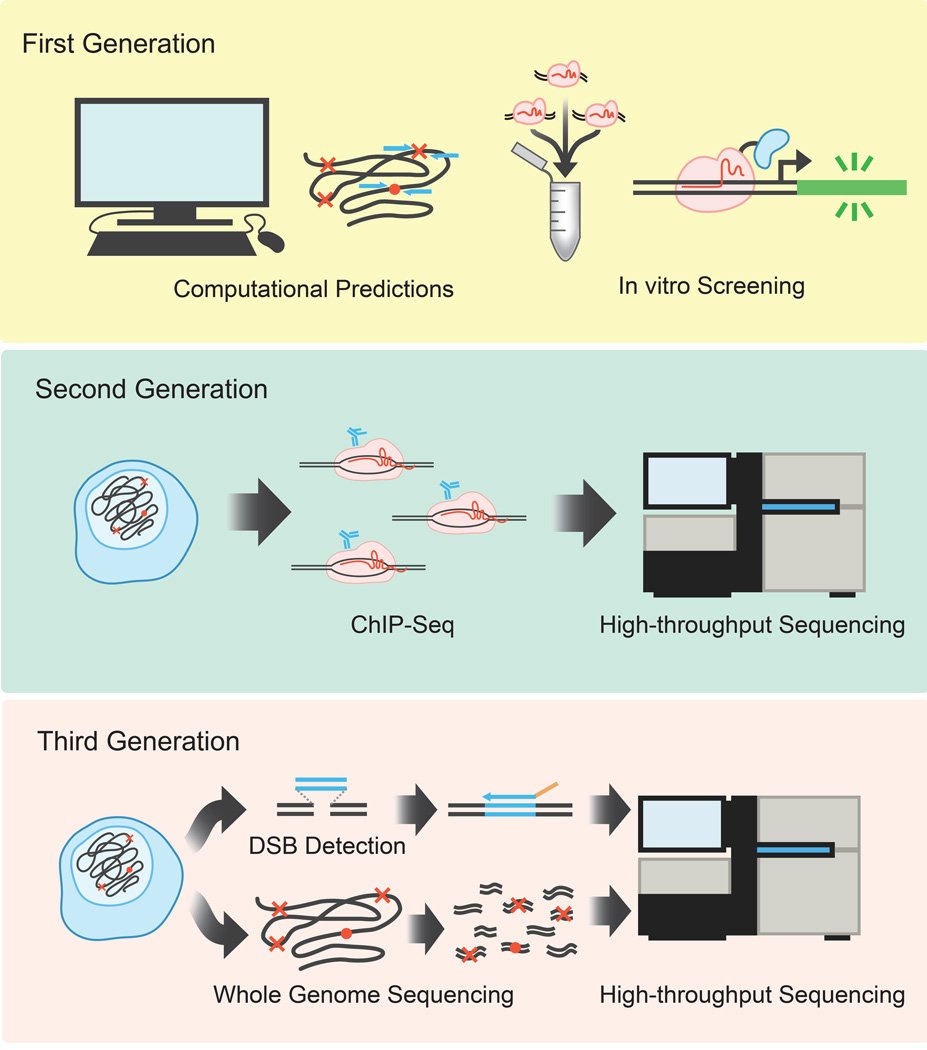

The RNA-guided clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) endonuclease system has taken the genome editing field by storm. The complex consists of the Cas9 nuclease protein and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that targets a specific DNA sequence through RNA-DNA base pairing (Figure 1) [1]. The most widely used Cas9, derived from Streptococcus pyogenes, targets a 20 nucleotide DNA sequence immediately followed by a 5’-NGG-3’ protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) [1]. The first studies of Cas9 specificity focused on off-target cleavage activity at genomic regions that were identified by computational prediction based on similarity to the target sequence [2–5], in vitro cleavage assays [6], or high-throughput reporter screens [7] (Figure 2, top). Predicted sites were analyzed for cleavage using a PCR-based assay. Some studies suggested high frequency of CRISPR/Cas9 activity [2,5], which alarmed the entire field and established expectations for follow-up studies to identify high off-target activity. However, other studies found modest or low off-target activity at predicted genomic sites [3,6] (Table 1). Results varied widely, even within a single research study. For example, among the six target sites tested by Fu and colleagues [2], no off-target sites were identified for two targets (RNF2 and FANCF), only one off-target site was detected for EMX1, while 4, 12 and 7 off-target sites were observed for VEGFA sites 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Thus, there was a clear distinction between very high target specificity of some sgRNAs (RNF2, FANCF), while others were very promiscuous (VEGFA sites 2 and 3) (Table 1). Despite this variance, the promiscuous VEGFA sgRNAs became the archetypal poster child for off-target activity and would be used in many subsequent studies. While it certainly makes sense to use promiscuous sgRNAs to test new methods for off-target site detection and avoidance, one should not assume that CRISPR/Cas9 per se has high off-target activity. Perhaps the most accurate conclusion from these early studies would be that CRISPR/Cas9 has the potential to be highly specific or lead to high-frequency off-target activity depending on the choice of sgRNA.

Figure 1. CRISPR/Cas9 specificity is dependent on its sgRNA.

The Cas9 protein (pink) complexes with a single guide RNA (sgRNA, red) at a DNA target site that contains a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM, blue box). The 5’ end of the sgRNA forms a 20-bp heteroduplex with one strand of the DNA. The binding or cleavage events facilitated by the Cas9/sgRNA complex can be categorized as highly specific (no off-targets), intermediate (1 to 5 off-targets) and promiscuous (6 or more off-targets).

Figure 2. A diversity of methods has been used to predict or detect off-target sites.

Each successive methodology attempted to be less biased and interrogate more of the genome than the previous generation.

Table 1.

Categorized sgRNA specificity

| Study | Off-target prediction/ detection method |

Validation rate a |

sgRNA specificity based on validated off-target activity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly specific (0 off-targets) |

Intermediate (1–5 off-targets) |

Promiscuous (>5 off-targets) |

||||

| Computational prediction & In vitro screen | Mali et al. 2013 | Reporter gene screen | <1% | n.d.b (artificial target sites) | ||

| Cho et al. 2013 | Computational & Exome capture | <1% | C4BPB CCR5 |

|||

| Fu et al. 2013 | Computational | <1% | RNF2 FANCF |

EMX1 VEGFA site 1 |

VEGFA site 2 (12) VEGFA site 3 (7) |

|

| Hsu et al. 2013 | Computational | <1% | EMX site 1 EMX site 3 |

|||

| Pattanayak et al. 2013 | Computational & In vitro screen | <1% | CLTA4 (3) | |||

| Cradick et al. 2013 | Computational | <1% | 9 sgRNAs c | 10 sgRNAs c | ||

| Lin et al. 2014 | Computational (gRNA and DNA bulges) | <1% | n.d.b (focus on DNA/RNA bulges, not mismatches) | |||

| Genome-wide detection of dCas9 binding | Wu et al. 2014 | ChIP-seq | <1% d | Nonog-sg3 Phc1-sg1 Phc1-sg2 |

Nanog-sg2 | |

| Cecnic et al. 2014 | ChIP-seq | <1% d | sgp53-3 | sgp53-1 | ||

| Kuscu et al. 2014 | ChIP-seq | <1% d | ||||

| O'Geen et al. 2015 | ChIP-seq & Sequence capture | <1% d | S1 | S2 | ||

| Gersbach et al. 2015 | ChIP-seq & RNA-seq | 3–17 % | IL1RN HBG1/2 |

|||

| Genome-wide detection Of DSBs and NHEJ | Tsai et al. 2015 | GUIDE-seq | 80% | RNF2 | HEK 293 site 2 HEK 293 site 3 |

VEGFA site 1 (21) VEGFA site 2 (151) VEGFA site 3 (59) EMX1 (15) FANCF (8) HEK293 site 1 (9) HEK 293 site 4 (133) |

| Kim et al. 2015 | Digenome-seq | 7–10% | HBB | VEGFA (81) | ||

| Ran et al. 2015 | BLESS | 14–41% | Pcsk9 | EMX1-sg1 | EMX-sg2 (12) | |

| Frock et al. 2015 | HTGTS (focus on translocation) | n.d.b | RAG1B | RAG1A | ||

| Wang et al. 2015 | IDLV | 100% e | WAS CR-3 TAT CR-4 TAT CR-6 |

WAS CR-5 TAT CR-1 |

WAS CR-4 (12) | |

Validation rate serves only as a reference and is highly dependent on the sensitivity of the method, the number of sgRNAs tested, and the number of potential off-target sites used for validation.

n.d., not determined

Only one potential off-target site was examined.

ChIP-seq detection is based on DNA binding while validation is based on DNA cleavage activity. Both methods have different specificity determinants and cannot be directly compared.

Additional sites that were not identified by IDLV were validated after computational prediction.

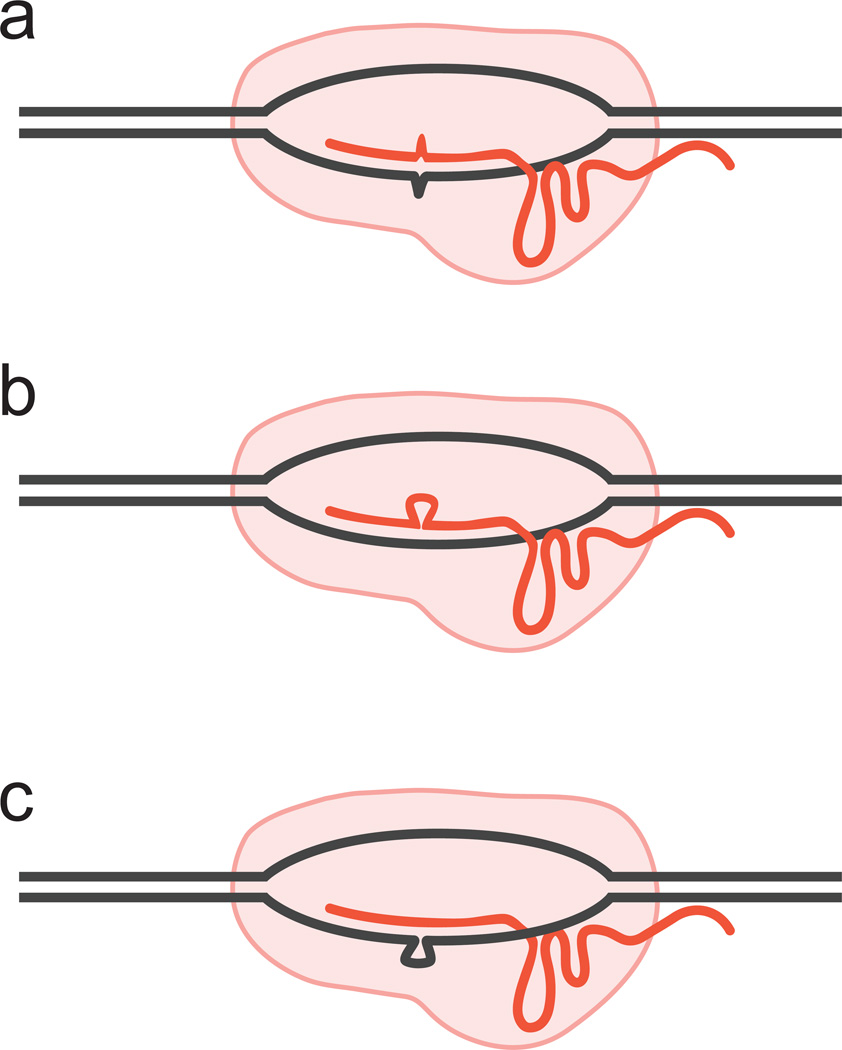

This conclusion notwithstanding, concerns about specificity led to several strategies to reduce off-target effects while retaining efficient on-target cleavage (reviewed in [8]). Heterodimeric Cas9 variants, such as paired Cas9 nickases and dimeric Cas9-FokI nucleases rely on targeting via two sgRNAs significantly enhanced specificity [9,10]. Modified sgRNAs can effectively reduce off-target activity by, paradoxically, the addition of two extra guanine nucleotides to the 5’ end (GGN---20-NGG) of the traditional sgRNA design (GN19-NGG) [4], or the use of truncated sgRNAs (GN17-NGGor GN18-NGG) [11,12]. In addition to mismatches, some sgRNAs can also tolerate DNA sequences with an extra base (DNA bulge) or a missing base (sgRNA bulge) [13] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Some sgRNAs allow binding or cleavage at variants of the target site.

In addition to single-base mismatches (a), some sgRNAs can tolerate DNA sequences with an extra base (b, DNA bulge) or a missing base (c, sgRNA bulge).

There is an expanding list of algorithms available that search the genome for similar sites adjacent to the Cas9 PAM, allowing a certain number of mismatches to the target site [3,14–17]. However, since predictive first generation methods could only survey a subset of potential off-target sites, a much larger number of off-target sites in the entire genome was expected. This assumption highlighted the need for unbiased and genome-wide detection of Cas9 off-target activity.

Second generation methods: Genome-wide binding specificity of nuclease-inactive dCas9

The catalytically inactive dCas9 has been used as a simple programmable DNA-binding platform for many applications including transcriptional activation and repression (CRISPRa and CRISPRi, respectively) [18–23]. Since dCas9 regulators do not possess nuclease activity, several groups performed ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by high throughput sequencing) to determine CRISPR/dCas9 binding specificity on a genome-wide scale [24–27] (Figure 2, middle). Virtually all studies observed the highest intensity binding at the target site, suggesting a strong binding preference for the target. However, less-intense off-target sites were detected varying from a few to hundreds or thousands of binding sites. The wide variation in off-target sites observed between different groups was likely due to differences in their experimental and analytical methods, in addition to any differences between individual sgRNAs. Off-target sites often contained motifs that were identical to the PAM proximal target sequence. Overall, these studies suggested that ChIP-seq identifies stable dCas9 binding to genomic target sites as well as transient binding of dCas9 to regions with partial complementarity as it scans the genome. Transient binding of Cas9 and dCas9 had been demonstrated in vitro and, interestingly, DNA cleavage only occurred at target sites and not at sites of transient interaction [28]. The lack of cleavage at transient sites in vitro was borne out in vivo. In fact, some studies were only able to observe cleavage at none or one off-target site [24,25,27] (Table 1).

However, subsequent third-generation methods would show that the near-perfect specificity of dCas9 in ChIP-seq assays might be an underestimation of the true off-target behavior of catalytically active Cas9. This discrepancy might be attributed to different determinants for Cas9 binding and nuclease activity, or structural differences between Cas9 and dCas9. Indeed a structure of dCas9 bound to DNA showed the HNH endonuclease domain located away from the scissile phosphate group of the target DNA strand, suggesting activity-dependent conformational rearrangements [29]. However, the results of these studies are still valid for all dCas9 applications, and generally showed that binding of dCas9 was very highly specific.

Third generation methods: Genome-wide detection of Cas9-induced double strand breaks

Double strand breaks (DSB) in the DNA of most species can be repaired by a highly efficient but error-prone nonhomologous end-joining pathway, leading to the accumulation of mutations at the breakpoint. Therefore, the most intuitive and comprehensive approach to identify DSB induced by catalytically active Cas9 across the whole genome is to search for mutations using whole genome sequencing (WGS, Figure 2, bottom). WGS of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) clones generated by CRISPR/Cas9 treatment suggested high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 [30,31]. In addition to the on-target site, one WGS study identified one high-frequency off-target that was not present in the reference genome, but rather created by a single nucleotide variation in that particular iPSC line [32]. This brings up the issue of sequence variation between individual genomes that will need to be addressed moving forward. Each genome is unique, possibly leading to off-targets that are not present in one individual but may be present in another. However, while WGS can readily detect high-frequency events, it is limited by the need of extensive sequencing depth. The typical 30x–60x coverage of the genome is not sufficient to identify low-level mutations. Digenome-seq also relies on WGS sequencing of nuclease digested genomic DNA, but Cas9-induced insertion and deletions are identified by their sequence signature rather by divergence from the reference genome [33]. However, sequencing depth and cost remains a limiting factor, especially when using non-human cells.

The need for accurate and unbiased detection of Cas9-induced off-targets on a genome wide scale has led researchers to adopt and develop new methods (reviewed in [8,34]). Integrase-deficient lentivirus vectors (IDLV) were able to identify off-target sites by integrating a marker gene at Cas9-induced DSBs [35], based on methods developed earlier for zinc finger nucleases [36]. Depending on sgRNA used, detected off-targets varied from zero to seven (Table 1), but no off-target sites were observed with paired Cas9 nickases. A similar approach, genome-wide unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq), identifies DSB by inserting small barcoded pieces of DNA followed by high throughput sequencing [37]. Among seven sgRNAs, off-target activity varied widely from zero (RNF2) to as many as 151 off-targets (VEGFA site 2) (Table 1). Thus, these studies recapitulated the same basic message that we learned from the first generation methods, that CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage has the potential for high or low specificity depending on the sgRNA.

In addition to insertion and deletion mutations, Cas9 also induces chromosomal translocations between breakpoints at on- and off-target sites and double strand break hotspots that are independent of Cas9. Translocation events can be determined by several methods, such as GUIDE-seq [37] and high-throughput, genome-wide, translocation sequencing (HTGTS) [38]. No translocation events were detected by HTGTS for two of the four sgRNAs targeting the RAG1 locus. In contrast, a large number of translocations were observed with the promiscuous sgRNA (VEGFA site 2), whose high off target activity has previously been reported [2,33,37] (Table 1). DSB hot spots can vary between cell types, which may contribute to cell-type specific off-target effects. Recently, DSB hotspots of individual genomes have been mapped revealing common and unique hotspots [39]. It will be interesting to define determinants of DSB hotspots to reduce the risk of deleterious consequences by irreversible changes to the genetic information.

Conclusions and prospectus

It is evident that major differences in CRISPR/Cas9 specificity arise from sgRNAs themselves. While some sgRNAs have the potential to be highly specific, others are promiscuous leading to hundreds of off-targets (Table 1). Therefore, it would seem inappropriate to suggest that the CRISPR/Cas9 platform per se is specific or non-specific. The current challenge is to anticipate which sgRNA will provide high on-target activity while having minimal off-target effects. In this regard, CRISPR/Cas9 maintains a technological advantage over zinc finger and transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins, which can also be highly specific but require more effort to assembly each new protein to test.

A deeper analysis of Cas9 orthologs from other species may reveal greater or less specificity for a given target site. Cas9 orthologs often vary in target site and PAM requirements [22,40,41]. The genome-wide nuclease activity of the S. aureus Cas9 was assessed using BLESS (direct in situ breaks labeling, enrichment on streptavidin and next-generation sequencing) [41]. Interestingly, SaCas9 displayed higher specificity than SpCas9. Furthermore, no off-target activity was observed in the mouse neuroblastoma cell line or mouse liver after AAV delivery of SaCas9 and Pcsk9 sgRNAs [41]. Further analysis is also required to understand how chromatin structure and sequence context contribute to target site accessibility, as well as on- and off-target site recognition. Off-target binding correlated with DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS) characteristic for accessible chromatin regions, and preferentially localized to regions void of DNA methylation [24–26]. Sequence features that contribute to sgRNA efficiencies have been systematically assessed in order to construct a predictive sequence model for the design of CRISPR/Cas9 knockout experiments [14,42]. There was a distinct preference for a guanine nucleotide immediately preceding the PAM site and nucleotide composition downstream of the PAM site also contributed to sgRNA efficiency. More recently, sequence context on sgRNA efficiency was also assessed for CRISPRi/CRISPRa [14]. These studies again found the sequence preference of CRISPRi/CRISPRa to be distinctly different from CRISPR knockout experiments. While these models are not perfect, they are a step towards improvement of sgRNA design for gene editing and regulation. Solving the challenge of optimal sgRNA selection will likely require large data sets of many sgRNAs in different cell types. Cell types for which large amounts of genomic data are already available, such as the ENCODE Tier 1 cell lines [43], would be more informative than the HEK293 and U2OS cells used frequently in the past.

The number of off-target events that could be tolerated by any sgRNA may also depend on the application. Changes to the genome by a Cas9 endonuclease are irreversible at off-target sites, which could lead to deleterious effects. One could argue that a single off-target site is too much when genomic DNA is permanently altered. Introducing CRISPR/Cas9 into a patient for gene therapy, with the potential to modify millions of cells and cell descendants, would require the highest specificity. However, there may be few off-target events in any single Cas9-treated iPSC, which could be clonally expanded and off-target events verified by WGS of that one genome. A modest number of off-target bindings might also be acceptable when using dCas9 to regulate transcription without altering the genetic content [18–20,23], even in clinical applications.

In conclusion, the current data suggest that careful selection of the sgRNA used with SpCas9 can produce a very highly specific DNA nuclease that would be appropriate for most if not all applications. Today’s computation design programs can help find target sites with minimal similarity to off-targets in a reference genome, but empirical testing in the appropriate cell type will likely be required to ensure optimal specificity performance. With more data sets of sgRNAs with SpCas9 and others in well annotated genomes and epigenomes, improved computational approaches will likely reduce the need for empirical testing to produce specific CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases and gene regulators.

Highlights.

Concerns about CRISPR specificity led to new methods for detection and avoidance

Some studies reported many off-target events, while others observed few

High or low specificity is a property of the guide RNA used, not CRISPR/Cas9 per se

The current challenge is to find the most specific guide RNA

The specificity determinants for Cas9 nuclease and dCas9 binding are different

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the W.M. Keck Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (GM097073).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Henriette O’Geen, Email: hhorvath@ucdavis.edu.

Abigail S. Yu, Email: abiyu@ucdavis.edu.

David J. Segal, Email: djsegal@ucdavis.edu.

References

- 1.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Joung JK, Sander JD. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31(9):822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. First large study to demonstrate that some sgRNA promote promiscous off-target clevage events, with some off-target sites used as much or more often than the on-target site. However, other sgRNAs in this study showed no off-target activity.

- 3. Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, Cradick TJ, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31(9):827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. Pulbished in the same issue as Fu et al., this study found only intermediate levels of off-target activity, presenting CRISPR/Cas as fairly specific.

- 4.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim Y, Kweon J, Kim HS, Bae S, Kim JS. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014;24(1):132–141. doi: 10.1101/gr.162339.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cradick TJ, Fine EJ, Antico CJ, Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9 systems targeting beta-globin and CCR5 genes have substantial off-target activity. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(20):9584–9592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, Ma E, Doudna JA, Liu DR. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):839–843. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. Cas9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31(9):833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo T, Lee J, Kim JS. Measuring and reducing off-target activities of programmable nucleases including CRISPR-Cas9. Molecules and cells. 2015;38(6):475–481. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai SQ, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, Foden JA, Thapar V, Reyon D, Goodwin MJ, Aryee MJ, Joung JK. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(6):569–576. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, Zhang F. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154(6):1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, Joung JK. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(3):279–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyvekens N, Topkar VV, Khayter C, Joung JK, Tsai SQ. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI-dCas9 nucleases (RFNs) directed by truncated grnas for highly specific genome editing. Human gene therapy. 2015;26(7):425–431. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin Y, Cradick TJ, Brown MT, Deshmukh H, Ranjan P, Sarode N, Wile BM, Vertino PM, Stewart FJ, Bao G. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(11):7473–7485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku402. This study was the first to demonstrate that some sgRNAs could tolerate DNA and RNA bulges, revealing a class of off-target sites that had been unknown. Even now, most computational design programs do not consider bulges.

- 14. Xu H, Xiao T, Chen CH, Li W, Meyer CA, Wu Q, Wu D, Cong L, Zhang F, Liu JS, Brown M, et al. Sequence determinants of improved CRISPR sgRNA design. Genome research. 2015;25(8):1147–1157. doi: 10.1101/gr.191452.115. This is perhaps the most comprensive analysis of sequence features that contribute to sgRNA efficiencies to date.

- 15.MacPherson CR, Scherf A. Flexible guide-RNA design for CRISPR applications using protospacer workbench. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33(8):805–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-offinder: A fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1473–1475. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montague TG, Cruz JM, Gagnon JA, Church GM, Valen E. CHOPCHOP: A CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:W401–W407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku410. (Web Server issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154(2):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Pinera P, Kocak DD, Vockley CM, Adler AF, Kabadi AM, Polstein LR, Thakore PI, Glass KA, Ousterout DG, Leong KW, Guilak F, et al. RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nature Methods. 2013;10(10):973–976. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeder ML, Linder SJ, Cascio VM, Fu Y, Ho QH, Joung JK. CRISPR RNA-guided activation of endogenous human genes. Nature Methods. 2013;10(10):977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilton IB, D'Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, Gersbach CA. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):510–517. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kearns NA, Pham H, Tabak B, Genga RM, Silverstein NJ, Garber M, Maehr R. Functional annotation of native enhancers with a cas9-histone demethylase fusion. Nature Methods. 2015;12(5):401–403. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152(5):1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Geen H, Henry IM, Bhakta MS, Meckler JF, Segal DJ. A genome-wide analysis of Cas9 binding specificity using ChIP-seq and targeted sequence capture. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43(6):3389–3404. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X, Scott DA, Kriz AJ, Chiu AC, Hsu PD, Dadon DB, Cheng AW, Trevino AE, Konermann S, Chen S, Jaenisch R, et al. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(7):670–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J, Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(7):677–683. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cencic R, Miura H, Malina A, Robert F, Ethier S, Schmeing TM, Dostie J, Pelletier J. Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)-distal sequences engage CRISPR Cas9 DNA target cleavage. PloS one. 2014;9(10):e109213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. 2014;507(7490):62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimasu H, Ran FA, Hsu PD, Konermann S, Shehata SI, Dohmae N, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nureki O. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2014;156(5):935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith C, Gore A, Yan W, Abalde-Atristain L, Li Z, He C, Wang Y, Brodsky RA, Zhang K, Cheng L, Ye Z. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human ipscs. Cell stem cell. 2014;15(1):12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veres A, Gosis BS, Ding Q, Collins R, Ragavendran A, Brand H, Erdin S, Cowan CA, Talkowski ME, Musunuru K. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell stem cell. 2014;15(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Grishin D, Wang G, Aach J, Zhang CZ, Chari R, Homsy J, Cai X, Zhao Y, Fan JB, Seidman C, et al. Targeted and genome-wide sequencing reveal single nucleotide variations impacting specificity of Cas9 in human stem cells. Nature communications. 2014;5(5507) doi: 10.1038/ncomms6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim D, Bae S, Park J, Kim E, Kim S, Yu HR, Hwang J, Kim JI, Kim JS. Digenome-seq: Genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nature methods. 2015;12(3):237–243. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3284. 231 p following 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X, Kriz AJ, Sharp PA. Target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Quantitative biology. 2014;2(2):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s40484-014-0030-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Wang Y, Wu X, Wang J, Wang Y, Qiu Z, Chang T, Huang H, Lin RJ, Yee JK. Unbiased detection of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33(2):175–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabriel R, Lombardo A, Arens A, Miller JC, Genovese P, Kaeppel C, Nowrouzi A, Bartholomae CC, Wang J, Friedman G, Holmes MC, et al. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29(9):816–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, Liebers M, Topkar VV, Thapar V, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, Iafrate AJ, Le LP, Aryee MJ, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(2):187–197. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frock RL, Hu J, Meyers RM, Ho YJ, Kii E, Alt FW. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33(2):179–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pratto F, Brick K, Khil P, Smagulova F, Petukhova GV, Camerini-Otero RD. DNA recombination. Recombination initiation maps of individual human genomes. Science. 2014;346(6211):1256442. doi: 10.1126/science.1256442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esvelt KM, Mali P, Braff JL, Moosburner M, Yaung SJ, Church GM. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nature methods. 2013;10(1116–1121) doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, Zetsche B, Shalem O, Wu X, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature. 2015;520(7546):186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14299. This is the first off-target analysis of a Cas9 ortholog. It also describes one of the third generation methods (BLESS) for the direct detection of double strand breaks.

- 42.Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, Tothova Z, Hegde M, Smith I, Sullender M, Ebert BL, Xavier RJ, Root DE. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(12):1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Consortium EP, Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]