Abstract

Background: The prevalence of thyroid cancer survivors is rising rapidly due to the combination of an increasing incidence, high survival rates, and a young age at diagnosis. The physical and psychosocial morbidity of thyroid cancer has not been adequately described, and this study therefore sought to improve the understanding of the impact of thyroid cancer on quality of life (QoL) by conducting a large-scale survivorship study.

Methods: Thyroid cancer survivors were recruited from a multicenter collaborative network of clinics, national survivorship groups, and social media. Study participants completed a validated QoL assessment tool that measures four morbidity domains: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual effects. Data were also collected on participant demographics, medical comorbidities, tumor characteristics, and treatment modalities.

Results: A total of 1174 participants with thyroid cancer were recruited. Of these, 89.9% were female, with an average age of 48 years, and a mean time from diagnosis of five years. The mean overall QoL was 5.56/10, with 0 being the worst. Scores for each of the sub-domains were 5.83 for physical, 5.03 for psychological, 6.48 for social, and 5.16 for spiritual well-being. QoL scores begin to improve five years after diagnosis. Female sex, young age at diagnosis, and lower educational attainment were highly predictive of decreased QoL.

Conclusion: Thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment can result in a decreased QoL. The present findings indicate that better tools to measure and improve thyroid cancer survivor QoL are needed. The authors plan to follow-up on these findings in the near future, as enrollment and data collection are ongoing.

Introduction

The incidence of thyroid cancer has increased substantially worldwide in the past several decades (1–3). A recent study suggested that thyroid cancer will double in incidence by 2019, making it the third most common cancer in women of all ages, and the second most common cancer in women younger than 45 years of age in the United States (4). Even though thyroid cancer incidence is increasing, survival has remained stable with a 10-year survival rate for papillary thyroid cancer (the most common type of thyroid cancer) as high as 97% in some studies (5,6). A rising incidence combined with a high rate of survival and a young age at diagnosis is resulting in a high prevalence of thyroid cancer survivors. If these trends continue, thyroid cancer could represent up to 10% of all cancer survivors in the United States in the near future.

As thyroid cancer can have a high rate of recurrence (7), thyroid cancer survivors require extended and often lifelong cancer surveillance that can be anxiety provoking. This is particularly important to thyroid cancer survivors because data show that recurrence and even death from thyroid cancer can happen as long as 40 years after the diagnosis (7). These patients also require lifelong thyroid hormone replacement that can be difficult to adjust early on in treatment, and some patients struggle with lifelong adjustment needs (8). Anecdotal evidence from physicians who treat thyroid cancer patients suggests that there is a subgroup of survivors who have significant physical and psychosocial needs after treatment for thyroid cancer. However, this subgroup has not been adequately described, despite growing evidence of unmet needs (8–11). This poses a challenge for the development of effective survivorship care plans that are intended to improve the quality of care of survivors as they move beyond cancer treatment.

Most studies on thyroid cancer survivorship in North America have reported a modest decrease in quality of life (QoL) after treatment (12–22). However, careful review of these data shows that the study populations were small, the tools were inconsistent and not tailored for thyroid cancer survivors, the sampling techniques did not take into account the varied survivor populations found in modern society, and only five small studies were conducted in the United States (12,14,16,18,19). Without improved information on thyroid cancer QoL outcomes, it will not be possible to develop monitoring tools, intervention strategies, and thyroid cancer–specific survivorship care plans that are relevant to survivor needs.

Here, a large-scale cross-sectional assessment of thyroid cancer survivors was conducted, specifically directed toward QoL issues surrounding thyroid cancer diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management. This is a report on the outcomes of the first 1174 thyroid cancer survivors from across the United States and Canada who were recruited into this thyroid cancer survivorship cohort (the North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study [NATCSS]). NATCSS is an ongoing prospective cohort study of thyroid cancer survivorship.

Methods

This study focused on short- and long-term (more than five years) thyroid cancer survivors recruited from a multicenter clinical collaboration (led by the University of Chicago) and from thyroid cancer survivor support groups and social media. The data collection strategy was intentionally designed to recruit using a varied approach to quantify differences between patients from clinics, those who actively participate in survivor groups, and those engaged in social media related to cancer. Quantitative elements of the validated thyroid cancer–specific City of Hope-QoL tool (http://prc.coh.org/pdf/Thyroid%20QOL.pdf) were combined with qualitative elements of open-ended questions and narrative data. Additional questions were added to the City of Hope tool after a panel of expert physicians evaluated the City of Hope tool questions and determined that there were key thyroid cancer–specific elements missing from the tool. In addition, this was a dedicated effort to integrate emerging data into follow-up efforts and eventually to improve upon assessment tools.

Sample and setting

Thyroid cancer survivors were recruited from across the United States and Canada (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy) using two mechanisms beginning in October 2013. Participants were recruited through the medical and surgical thyroid cancer clinics at University of Chicago as well as The University of Arizona, The University of California at San Francisco, Columbia University, Harvard University, McGill University, and The University of Rochester. Participants were also recruited through the Thyroid Cancer Survivors Association (ThyCa), Bite Me Cancer, Thyroid Cancer Canada, and social media. Participants were eligible for participation if they had a prior diagnosis of thyroid cancer of any subtype, and were 18 years of age or older.

Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the University of Chicago's Institutional Review Board prior to study initiation. All eligible participants volunteered for participation during a clinic visit or by filling out an online interest form. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (either in person or retuned in the mail) prior to study participation. This included consent to ascertain medical records such that the tumor characteristics and treatment-related information could be validated in a subset of participants. Following informed consent, participants completed a survivorship assessment survey that included basic demographics as well as outcome measures to assess tumor characteristics, overall QoL (including physical, psychosocial, and spiritual morbidity), and health concerns and challenges. The survey was administered using either a hard-copy questionnaire or an electronic link to the questionnaire on REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a browser-based research database.

Instruments

Basic participant demographics were obtained as well as cancer-related questions, including age at diagnosis, time since completion of treatment, type of treatment, tumor histology subtype, tumor size, cancer stage, and whether they had experienced a second cancer occurrence (either a tumor relapse or a second primary malignancy). Type of surgical treatment documented included lobectomy, near-total thyroidectomy, total thyroidectomy, and lymphadenectomy. Other treatments documented included thyroid hormone suppression, radioiodine therapy (RAI), chemotherapy, and external beam radiation. QoL was assessed using the City of Hope-QOL Scale (a thyroid-specific validated assessment tool), using questions generated by the authors of the study to incorporate areas of QoL changes that were not addressed by the City of Hope-QoL tool, and using an open-ended question allowing patients to add concerns not addressed by the questionnaire (“Have you had any other complication or problem related to your thyroid cancer or its treatment not covered by the questionnaire?”). The thyroid cancer–specific City of Hope-QoL tool measured physical, psychological, social, and spiritual wellbeing on a scale from 0 to 10 (with 0 being the worst and 10 the best).

Data analysis

Hardcopy data were converted and stored in electronic format by entering the data into REDCap. Data from REDCap were downloaded into a SAS data set (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) for final analysis. Overall QoL and sub-scores and their associations with clinical measures were compared by using simple summation scoring to produce domain scores and a total score, with higher scores corresponding to greater impairment. t-Tests (for normally distributed variables) or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for non-normally distributed variables) were used to compare mean scores between subjects based on demographic and tumor characteristics. Multivariable linear regression was also used to examine the relationship between the QoL scores and potential predictors. Means, standard deviations, item–scale correlations, Cronbach's alpha, and inter-scale correlations were used to examine whether the scores satisfied the scaling assumptions of the thyroid cancer–specific City of Hope QoL tool. In all analyses, p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Basic cohort demographics are presented in Table 1. A total of 1174 participants completed the questionnaire, of whom 1055 (89.9%) were female. The mean age of the study cohort was 48 years (range 18–88 years). The majority of participants were non-Hispanic whites (95.9%), with 68.6% being currently married, and 67.5% never having smoked. Overall, 32.6% of participants reported having a high school degree, and 67.3% were college educated. Sixty-nine percent of participants reported having the papillary subtype, 15.8% mixed tumor type, 5.6% follicular, 3.9% medullary, and <1% anaplastic. The majority of participants had surgery (94.9%) and RAI treatment (77.2%), but very few had external beam radiation (3.2%) or chemotherapy (0.7%). More participants reported being stage 1 (33.9%) than any other stage. The majority of the participants were recruited from survivorship groups (79.2%), with 7.2% being recruited in the clinics and 2.4% from social media.

Table 1.

Demographic and Tumor Characteristics at Baseline for NATCSS Participants

| Demographic characteristics | Cases, n (%) | Tumor characteristics | Cases, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1174 | Histology | |

| Papillary | 809 (69.2) | ||

| Sex | Follicular | 65 (5.6) | |

| Female | 1055 (89.9) | Medullary | 45 (3.9) |

| Male | 119 (10.1) | Anaplastic | 2 (0.2) |

| Mixed | 185 (15.8) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Other | 27 (2.3) | |

| White | 1126 (95.9) | Don't know | 36 (3.1) |

| Black | 14 (1.2) | ||

| Other | 34 (2.9) | Treatment | |

| Mean (SD) | Surgery | 1129 (94.9) | |

| Age at enrollment | 48.0 (16.9) | RAI | 919 (77.2) |

| Radiation | 38 (3.2) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 8 (0.7) | ||

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 806 (68.7) | Stage | |

| Ever | 367 (31.3) | 1 | 391 (33.9) |

| 2 | 184 (15.7) | ||

| Education | 3 | 170 (14.5) | |

| High school | 385 (32.8) | 4 | 95 (8.1) |

| College | 364 (31.0) | Don't know | 331 (28.3) |

| More than college | 420 (35.8) | ||

| Missing | Time since diagnosis | ||

| Marital status | 0–1 year | 289 (24.3) | |

| Married | 808 (68.8) | 1–2 years | 194 (16.3) |

| 2–3 years | 120 (10.1) | ||

| Annual household income | 3–4 years | 97 (8.2) | |

| <$35,000 | 106 (9.1) | 4–5 years | 95 (8.0) |

| $35,000–69,999 | 289 (24.8) | 5–10 years | 207 (17.4) |

| $70,000–119,999 | 330 (28.2) | 10–20 years | 123 (10.3) |

| ≥$120,000 | 281 (24.1) | 20+ years | 65 (5.5) |

| Refused | 160 (13.3) | ||

| Source of cases | |||

| Clinic | 86 (7.2) | ||

| Survivorship Groups (ThyCa, Bite Me Cancer) | 943 (79.2) | ||

| Social Media (Facebook, Twitter) | 28 (2.4) | ||

| Other (friends, etc.) | 117 (11.2) |

NATCSS, North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study; RAI, radioactive iodine.

Findings from the City of Hope assessment tool are presented in Table 2. The mean total QoL score for participants in the study population was 5.56 (standard deviation (SD) = 1.59), with a physical sub-score of 5.83 (SD = 1.99), a psychological sub-score of 5.03 (SD = 1.78), a social sub-score of 6.48 (SD = 2.29), and a spiritual sub-score of 5.16 (SD = 2.01). The lowest individual QoL scores were observed for distress of initial diagnosis (M = 2.35; SD = 2.67), distress of ablation (M = 2.84; SD = 2.82), distress from surgery (M = 3.00; SD = 2.69), fear of a second cancer (M = 3.77; SD = 3.11), and distress from withdrawal from thyroid hormone (M = 3.78; SD = 3.99). A lower mean score is observed for all sub-scores for one year or less from treatment compared with five or more years (data not shown). In addition, the mean sub-scores were consistently higher for the papillary type compared with the other thyroid cancer subtypes.

Table 2.

All City of Hope QoL Outcome Measures Assessed in This Study

| City of Hope QoL measures | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| To what extent are the following a problem: | ||

| Fatigue | 4.16 | 3.21 |

| Appetite changes | 6.41 | 3.23 |

| Aches or pain | 5.23 | 3.34 |

| Sleep changes | 4.81 | 3.50 |

| Constipation | 6.92 | 3.34 |

| Menstrual changes or fertility | 7.58 | 3.48 |

| Weight gain | 5.12 | 3.83 |

| Tolerance to cold or heat | 4.54 | 3.50 |

| Dry skin or hair changes | 4.75 | 3.54 |

| Voice changes | 6.93 | 3.48 |

| Motor skills/coordination | 7.54 | 3.04 |

| Swelling/fluid retention | 7.34 | 3.15 |

| Rate overall physical health | 4.93 | 2.71 |

| Total physical well-being | 5.83 | 1.99 |

| How difficult is it to cope? | 6.15 | 2.83 |

| How good is QoL? | 7.03 | 2.34 |

| How much happiness? | 6.93 | 2.27 |

| Do you feel like you are in control? | 6.01 | 2.63 |

| How satisfying is your life? | 6.93 | 2.27 |

| How is your ability to concentrate or remember things? | 5.31 | 2.64 |

| How useful do you feel? | 6.72 | 2.67 |

| Has illness caused changes in appearance? | 5.12 | 3.31 |

| Has illness changed self-concept? | 4.90 | 3.43 |

| How distressing were the following? | ||

| Initial diagnosis | 2.35 | 2.67 |

| Surgeries | 3.00 | 2.69 |

| Time since my treatment was completed | 5.10 | 2.85 |

| Ablation | 2.84 | 2.82 |

| Scanning | 4.70 | 3.30 |

| Thyroid testing | 6.40 | 3.15 |

| Withdrawal from thyroid hormone | 3.78 | 3.99 |

| How much anxiety do you have? | 5.05 | 2.96 |

| How much depression do you have? | 6.16 | 2.96 |

| To what extent are you fearful of: | ||

| Future diagnostic tests | 4.89 | 3.14 |

| A second cancer | 3.77 | 3.11 |

| Recurrence of your cancer | 4.17 | 3.23 |

| Spreading/metastasis | 4.46 | 3.39 |

| Total psychological well-being | 5.03 | 1.78 |

| How distressing has illness been for your family? | 4.13 | 2.77 |

| Amount of support you receive from others sufficient? | 7.10 | 2.89 |

| Interfering with your personal relationships? | 7.04 | 3.18 |

| Is sexuality impacted by illness? | 5.89 | 3.70 |

| To what degree has illness interfered with your employment? | ||

| Motivation to work | 5.93 | 3.48 |

| Time away from work | 6.32 | 3.44 |

| Productivity | 6.28 | 3.34 |

| Quality of work | 6.77 | 3.24 |

| Driving | 8.29 | 2.63 |

| Chores/home | 6.53 | 3.24 |

| Preparing meals | 7.18 | 3.01 |

| Leisure activities | 6.55 | 3.25 |

| How much isolation do you feel? | 6.52 | 3.39 |

| How much financial burden have you incurred? | 5.44 | 3.68 |

| Total social well-being | 6.48 | 2.29 |

| Importance of religious activities (praying, going to church)? | 4.91 | 4.07 |

| How important are spiritual activities such as meditation? | 4.01 | 3.62 |

| How much has your spiritual life changed? | 4.79 | 3.53 |

| How much uncertainty do you feel about your future? | 4.80 | 3.12 |

| To what extent has illness made positive changes in your life? | 4.62 | 3.16 |

| To what extent has illness given you purpose in your life? | 6.04 | 3.22 |

| How hopeful do you feel? | 6.82 | 2.46 |

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.16 | 2.01 |

| Total QoL | 5.56 | 1.59 |

N = 1174. 0 = lowest and 10 = highest QoL.

QoL, quality of life.

Several risk factors were identified for decreased QoL (Table 3). Females reported significantly lower total QoL (M = 5.48 for females and 6.32 for males, p < 0.001) and lower QoL sub-scores (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual) when compared with males (p < 0.001). It was also found that older people consistently reported higher total QoL and statistically significant higher mean scores for physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being compared with younger people, and that the association remains significant after adjustment for age, sex, type of thyroid cancer, and time from diagnosis (p < 0.001; Table 3). In addition, people who reported higher levels of education also reported significantly higher mean total and individual QoL sub-scores, with the exception of spiritual well-being. Tumor type, tumor stage, and treatment modality had no significant effect on QoL. When taken as a whole, the variable referral source of cases was not significantly associated with QoL. However, when the various referral sources individually were compared in a pair-wise fashion, the scores of patients recruited directly from clinic were significantly higher compared with those recruited from others sources (Table 3).

Table 3.

QoL and Sub-Scores According to the Associated Demographic, Clinical, and Recruitment Characteristics

| M (SD) | p* | M (SD) | p* | M (SD) | p* | M (SD) | p* | B | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Males | Females | ||||||||

| Total physical well-being | 7.12 (1.46) | <0.0001 | 5.70 (1.98) | <0.0001 | −1.33 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Total psychological well-being | 6.06 (1.84) | <0.0001 | 4.92 (1.73) | <0.0001 | −0.88 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Total social well-being | 7.58 (2.03) | <0.0001 | 6.35 (2.28) | <0.0001 | −1.04 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Total spiritual well-being | 4.47 (2.03) | <0.0001 | 5.23 (1.99) | <0.0001 | 0.9 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Total QoL | 6.32 (1.46) | <0.01 | 5.48 (1.58) | <0.01 | −0.63 | <0.01 | ||||

| Age | <35 | 35–50 | 50–65 | 65+ | ||||||

| Total physical well-being | 5.64 (1.86) | 0.69 | 5.48 (1.91) | <0.0001 | 6.01 (1.97) | 0.10 | 6.89 (1.97) | <0.0001 | 0.27 | <0.0001 |

| Total psychological well-being | 4.52 (1.64) | <0.01 | 4.75 (1.62) | <0.01 | 5.21 (1.77) | 0.07 | 6.51 (1.91) | <0.0001 | 0.37 | <0.0001 |

| Total social well-being | 5.96 (2.21) | 0.03 | 6.18 (2.22) | 0.02 | 6.71 (2.32) | 0.10 | 8.16 (1.92) | <0.0001 | 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Total spiritual well-being | 4.76 (1.88) | 0.01 | 5.02 (1.84) | 0.13 | 5.39 (2.11) | 0.02 | 5.39 (2.42) | 0.31 | 0.25 | <0.01 |

| Total QoL | 5.11 (1.52) | 0.01 | 5.31 (1.47) | 0.01 | 5.80 (1.57) | 0.03 | 7.04 (1.46) | <0.0001 | 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Education | High school | College | More than college | |||||||

| Total physical well-being | 5.28 (1.89) | <0.0001 | 6.02 (1.95) | <0.01 | 6.19 (2.00) | <0.01 | 0.24 | <0.0001 | ||

| Total psychological well-being | 4.51 (1.71) | <0.0001 | 5.24 (1.76) | <0.01 | 5.32 (1.75) | <0.01 | 0.24 | <0.0001 | ||

| Total social well-being | 5.97 (2.40) | <0.0001 | 6.75 (2.17) | <0.01 | 6.73 (2.21) | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.003 | ||

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.11 (2.10) | 0.46 | 5.11 (2.00) | 0.39 | 5.24 (1.94) | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ||

| Total QoL | 5.01 (1.56) | <0.0001 | 5.74 (1.53) | 0.01 | 5.91 (1.52) | <0.01 | 0.26 | <0.0001 | ||

| Tumor types | Papillary | Follicular | Medullary | |||||||

| Total physical well-being | 5.88 (1.93) | 0.02 | 5.93 (2.03) | 0.64 | 6.52 (1.90) | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.004 | ||

| Total psychological well-being | 5.04 (1.74) | 0.05 | 5.15 (1.75) | 0.48 | 5.03 (1.73) | 1.00 | −0.05 | 0.10 | ||

| Total social well-being | 6.52 (2.24) | 0.01 | 6.44 (2.18) | 0.98 | 6.82 (2.30) | 0.50 | −0.09 | 0.02 | ||

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.12 (2.0) | 0.23 | 4.83 (1.85) | 0.33 | 5.35 (1.91) | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.17 | ||

| Total QoL | 5.58 (1.55) | 0.03 | 5.52 (1.44) | 0.93 | 5.51 (1.44) | 0.90 | −0.05 | 0.10 | ||

| Stage | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | ||||||

| Total physical well-being | 5.82 (2.01) | 0.18 | 5.90 (1.95) | 0.69 | 5.68 (1.93) | 0.21 | 5.75 (1.95) | 0.29 | −0.03 | 0.35 |

| Total psychological well-being | 4.98 (1.75) | 0.26 | 4.95 (1.77) | 0.84 | 5.15 (1.66) | 0.85 | 5.03 (1.74) | 0.33 | −0.03 | 0.32 |

| Total social well-being | 6.55 (2.28) | 0.06 | 6.45 (2.19) | 0.96 | 6.39 (2.19) | 0.54 | 6.01 (2.39) | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.19 |

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.11 (2.01) | 0.89 | 5.07 (2.07) | 0.42 | 5.38 (2.04) | 0.16 | 5.31 (1.76) | 0.57 | −0.02 | 0.50 |

| Total QoL | 5.54 (1.56) | 0.11 | 5.57 (1.54) | 0.75 | 5.63 (1.49) | 0.73 | 5.42 (1.60) | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.14 |

| Treatment | Surgery | Radiation | RAI | Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Total physical well-being | 5.84 (1.99) | 0.11 | 5.78 (1.96) | 0.09 | 5.44 (2.28) | 0.08 | 5.36 (1.54) | 0.59 | −0.1 | 0.59 |

| Total psychological well-being | 5.03 (1.78) | 0.90 | 5.01 (1.76) | 0.39 | 5.17 (2.00) | 0.42 | 5.20 (0.98) | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.54 |

| Total social well-being | 6.50 (2.29) | 0.18 | 6.43 (2.25) | 0.08 | 6.42 (2.39) | 0.16 | 5.77 (1.59) | 0.70 | −0.09 | 0.70 |

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.15 (2.02) | 0.39 | 5.19 (1.99) | 0.69 | 5.40 (2.16) | 0.95 | 4.88 (2.16) | 0.35 | −0.19 | 0.35 |

| Total QoL | 5.56 (1.59) | 0.81 | 5.56 (1.57) | 0.46 | 5.60 (1.95) | 0.25 | 5.41 (0.87) | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.79 |

| Source of cases | Clinic | Survivorship groups | Social media | Other | ||||||

| Total physical well-being | 7.81 (1.63) | <0.0001 | 5.83 (1.96) | 0.80 | 6.41 (1.79) | 0.07 | 5.81 (2.11) | −0.04 | 0.80 | |

| Total psychological well-being | 6.55 (1.99) | 0.00 | 5.04 (1.74) | 0.35 | 5.41 (1.61) | 0.26 | 4.97 (1.92) | −0.13 | 0.35 | |

| Total social well-being | 7.99 (2.01) | 0.00 | 6.51 (2.29) | 0.26 | 7.27 (2.02) | 0.05 | 6.37 (2.30) | −0.2 | 0.26 | |

| Total spiritual well-being | 5.45 (1.92) | 0.30 | 5.14 (2.02) | 0.48 | 5.14 (2.04) | 1.00 | 5.24 (1.98) | 0.11 | 0.48 | |

| Total QoL | 6.95 (1.64) | 0.00 | 5.56 (1.58) | 0.98 | 6.13 (1.32) | 0.13 | 5.56 (1.65) | 0.003 | 0.98 |

p adjusted for age, sex, type of thyroid cancer, and time from diagnosis.

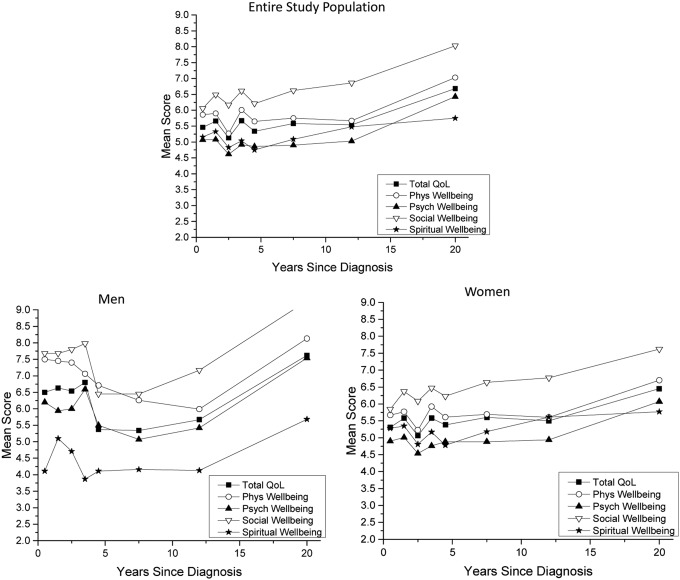

It was found that QoL exhibits a non-linear trend within the first five years of diagnosis, as evidenced by the observation of several decreases in mean overall QoL and mean QoL sub-scores in the early time points (Fig. 1). After five years, QoL plateaus and then gradually increases over time. The instability in QoL in the first five years is apparent in both men and women.

FIG. 1.

Quality of life (QoL) scores for years since diagnosis for entire study population and men and women separately.

The City of Hope tool only accounted for 51% of the variance in overall QoL. Variables accounting for the greatest variance of self-reported QoL (in order of importance) were fear (of second cancer, cancer recurrence, metastasis), complications from surgery and RAI, lack of support, impact on spiritual activities, uncertainty, self-concept, family distress, and fatigue (data not shown).

The prevalence of self-reported adverse consequences related to treatment was dramatically higher in this study population compared with what is commonly quoted by physicians based on current literature (Table 4). For example, the prevalence of voice change is 54.9% in this study population, while the literature would suggest this number should be no more than 5% (23). Likewise problems with hypocalcemia, the surgical incision, medication side effects, and weight gain were reported at a rate 10-fold higher than expected. Many participants also felt that communication from physicians regarding the risks of surgery (26.3%) and RAI (28.8%) were not adequately explained (data not shown). The study population also reported feeling a lack of support from both physicians (33.8%) and family members (23.1%). The most common concerns reported as the open-ended responses are shown in Table 5. The top five most commonly reported concerns were memory issues/brain fog, hair loss, bone changes/bone pain, dysphagia, and dry eyes.

Table 4.

Prevalence of Thyroid Cancer Issues in NATCSS

| Prevalence in NATCSS | Physician expected/quoted prevalence | |

|---|---|---|

| Change in everyday speaking voice or your singing voice | 54.9% | 5% |

| Treatment required to fix voice | 9.8% | 1% |

| Dry mouth symptoms | 61.9% | 1% |

| Low calcium requiring treatment with pills for more than two months | 31.6% | 1% |

| Low calcium that required readmission to the hospital | 8.4% | 0.50% |

| A problem with the incision | 7.5% | 1% |

| Bleeding that required a second operation to fix | 0.7% | 0.50% |

| Side effects from medications | 28.0% | 1–5% |

| Any other complication related to your thyroid cancer not asked in survey | 45.8% |

Table 5.

Most Common Open-Ended Responses

| Complaint | Count |

|---|---|

| Memory problems/brain fog | 28 |

| Hair loss | 24 |

| Bone changes/bone pain | 22 |

| Dysphagia | 17 |

| Dry eyes | 15 |

| Neuropathy | 14 |

| Dental issues | 11 |

| Additional surgeries | 10 |

| Brittle/dry nails | 9 |

| Visual changes | 7 |

Discussion

Based on the paucity of literature on thyroid cancer survivorship, it seems that long-term survival for patients with thyroid cancer has been perceived in the past as a relatively benign experience, particularly when compared with survivors of other cancers. This perception is likely because thyroid cancer has a good five-year survival rate. The current findings from the NATCSS illustrate that this perception is unfounded, and that thyroid cancer survivors experience several adverse physical, psychological, social, and spiritual challenges that linger for many years following treatment. It was also found that young age, female sex, decreased education, and participation in survivor groups (both traditional and through social media) are associated with decreased QoL. The present findings also suggest that current assessment tools are inadequate at measuring the full extent of challenges in the QoL of thyroid cancer survivors.

There were several unexpected findings in this study, some of which have relevance to all cancer survivors. The overall QoL of scores that were reported by the NATCSS cohort (5.56) are lower than recently reported City of Hope QoL scores of survivors of other cancer types that have worse survival and more invasive treatment, including colorectal cancer (mean QoL = 6.75) (24), breast cancer (mean QoL = 7.01) (25), and malignant glioma (mean QoL = 5.96) (26). Furthermore, no strong effect for tumor stage was seen in this study. These two findings together suggest that survival prognosis may have less correlation with QoL in cancer survivors than what would be expected. Furthermore, survivorship in these other cancers has been studied in more detail and has likely lead to more emphasis on caring for the psychosocial effects of these other types of cancer survivors. This leads us to hypothesize that improved assessment tools, increased awareness of the pitfalls of thyroid cancer survivorship, and creation of specific interventions could potentially lead to dramatic improvements in QoL in thyroid cancer survivors as well. Other unexpected findings include a substantially longer time to QoL normalization than expected, better QoL in older individuals, and a very high prevalence of perceived adverse outcomes when compared with what is expected (and commonly quoted) by physicians. It was anticipated that older persons would have more difficulty with recovery from treatment effects and thus would report worse outcomes, especially for physical effects. This finding is of particular importance given that thyroid cancer is increasingly being diagnosed in younger women (2).

Another important finding that has broad implications beyond thyroid cancer survivorship is the difference in QoL scores that were found between patients recruited directly from clinic compared with those recruited from traditional survivorship groups as well as from online and social media groups. It is possible that those patients who have had difficulties are more likely to seek out help via these support groups. It is possible that survivorship studies that do not take into account the source of the study population may under- or overestimate the effect of cancer on QoL.

This study illuminates several actionable items for current consideration and future study. First, thinking of thyroid cancer as a “good cancer” and describing it to patients in this manner may be unintentionally deleterious. While physicians may describe thyroid cancer in this manner as a well-intentioned means to alleviate fear and concern on the part of the patient, it may have the unintended consequence of making the patient feel as though their concerns are being minimized. This appears to be reflected in the NATCSS findings, as one third of participants reported that they feel that the side effects from their thyroid cancer are not being taken seriously by physicians, and a quarter of participants reported that their side effects are not taken seriously by their family members. This is consistent with previous findings (27). Second, the findings also suggest that a new assessment tool that more comprehensively assesses thyroid cancer survivorship needs to be developed and validated. Third, the data indicate that thyroid cancer survivorship care plans (SCPs) should include a means of monitoring adverse psychosocial outcomes, particularly within the first five years of survivorship, and specific interventions for these issues should be studied. The authors plan to utilize these data to insure that SCPs in their institution (and potentially elsewhere) are tailored to meet the needs of thyroid cancer survivors better. The data also provides a word of caution in interpreting future survivorship studies that do not take into account the diverse groups from which survivors are recruited.

It is acknowledged that there are several limitations to this study. Here, only baseline measures of QoL are reported, although follow-up data will be available in the future, as this is a longitudinal study. Another limitation is that self-reported data are presented. Although the vast majority of study participants have consented to their data being validated using medical records, this effort has not been undertaken extensively, as only 50 cases were validated. The medical record validation will be pursued extensively in the coming years. Another potential limitation is that many of the participants were recruited using social media, which could potentially introduce bias. However, the recruitment approach has resulted in a very large and potentially generalizable population. Strengths of this study include the large sample size, conferring the ability to stratify by important demographic and tumor characteristics, including sex and subtype. Another major strength of the study is that it has been designed specifically to allow improved assessment tools to be created and for these tools to be tested and validated. Future plans include testing and validating this new questionnaire and creating thyroid cancer–specific care plans.

Establishing a large and geographically diverse thyroid cancer survivorship cohort through collaboration with multiple institutions gives the ability to confer a better understanding of how thyroid cancer impacts the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual morbidity of survivors. These data will serve as the basis for longitudinal efforts to characterize QoL in thyroid cancer survivors. Given the rapidly increasing number of thyroid cancer survivors, and the need for assessment tool development, integration, and testing, this project will confer timely improvements in the understanding of thyroid cancer survivorship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at The University of Chicago. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (i) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (ii) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (iii) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (iv) procedures for importing data from external sources. This project was supported by the University of Chicago Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence. R.H.G. was supported by Award Number K12CA139160 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or The National Institutes of Health. We would also like to say thank you to our study participants and to the cancer survivorship groups that participated in the study, including ThyCa, Bite Me Cancer, and Thyroid Cancer Canada. Their participation has made this work possible.

Author Disclosure Statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Kilfoy BA, Zheng T, Holford TR, Han X, Ward MH, Sjodin A, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Zhu C, Guo GL, Rothman N, Zhang Y. 2009. International patterns and trends in thyroid cancer incidence, 1973–2002. Cancer Causes Control 20:525–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilfoy BA, Devesa SS, Ward MH, Zhang Y, Rosenberg PS, Holford TR, Anderson WF. 2009. Gender is an age-specific effect modifier for papillary cancers of the thyroid gland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:1092–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Ward MH, Sabra MM, Devesa SS. 2011. Thyroid cancer incidence patterns in the United States by histologic type, 1992–2006. Thyroid 21:125–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Brown R, Shih YT, Kaplan EL, Chiu B, Angelos P, Grogan RH. 2013. The clinical and economic burden of a sustained increase in thyroid cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22:1252–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). March 11, 2011/60(09);269–272 [PubMed]

- 6.Davies , Welch HG. 2010. Thyroid cancer survival in the United States: observational data from 1973 to 2005. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136:440–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grogan RH, Kaplan SP, Cao H, Weiss RE, Degroot LJ, Simon CA, Embia OM, Angelos P, Kaplan EL, Schechter RB. 2013. A study of recurrence and death from papillary thyroid cancer with 27 years of median follow-up. Surgery 154:1436–1446; discussion 1446–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husson O, Mols F, Oranje WA, Haak HR, Nieuwlaat WA, Netea-Maier RT, Smit JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. 2014. Unmet information needs and impact of cancer in (long-term) thyroid cancer survivors: results of the PROFILES registry. Psychooncology 23:946–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banach R, Bartès B, Farnell K, Rimmele H, Shey J, Singer S, Verburg FA, Luster M. 2013. Results of the Thyroid Cancer Alliance international patient/survivor survey: psychosocial/informational support needs, treatment side effects and international differences in care. Hormones (Athens) 12:428–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfarb M, Casillas J. 2014. Unmet information and support needs in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer: comparison of adolescents/young adults (AYA) and older patients. J Cancer Surviv 8:394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dingle IF, Mishoe AE, Nguyen SA, Overton LJ, Gillespie MB. 2013. Salivary morbidity and quality of life following radioactive iodine for well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148:746–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oren A, Benoit MA, Murphy A, Schulte F, Hamilton J. 2012. Quality of life and anxiety in adolescents with differentiated thyroid cancer. Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E1933–E1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Anello C. 1997. Quality-of-life changes in patients with thyroid cancer after withdrawal of thyroid hormone therapy. Thyroid 7:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bresner L, Banach R, Rodin G, Thabane L, Ezzat S, Sawka AM. 2015. Cancer-related worry in Canadian thyroid cancer survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:977–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts KJ, Lepore SJ, Urken ML. 2008. Quality of life after thyroid cancer: an assessment of patient needs and preferences for information and support. J Cancer Educ 23:186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah MD, Witterick IJ, Eski SJ, Pinto R, Freeman JL. 2006. Quality of life in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. J Otolaryngol 35:209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendozza A, Shaffer B, Karakla D, Mason ME, Elkins D, Goffman TE. 2004. Quality of life with well-differentiated thyroid cancer: treatment toxicities and their reduction. Thyroid 14:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz PN, Stava C, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R. 2003. Health profiles and quality of life of 518 survivors of thyroid cancer. Head Neck 25:349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun V, Borneman T, Koczywas M, Cristea M, Piper BF, Uman G, Ferrell B. 2012. Quality of life and barriers to symptom management in colon cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16:276–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer S, Lincke T, Gamper E, Bhaskaran K, Schreiber S, Hinz A, Schulte T. 2012. Quality of life in patients with thyroid cancer compared with the general population. Thyroid 22:117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husson O, Haak HR, Buffart LM, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Mols F, Kuijpens JL, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. 2013. Health-related quality of life and disease specific symptoms in long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol 52:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Husson O, Haak HR, Oranje WA, Mols F, Reemst PH, van de Poll-Franse LV. 2011. Health-related quality of life among thyroid cancer survivors: a systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75:544–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons 2012. Fourth national audit report. Available at: www.baets.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/4th-National-Audit.pdf (accessed July2015)

- 24.Sun V, Borneman T, Koczywas M, Cristea M, Piper BF, Uman G, Ferrell B. 2012. Quality of life and barriers to symptom management in colon cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16:276–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juarez G, Hurria A, Uman G, Ferrell B. 2013. Impact of a bilingual education intervention on the quality of life of Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40:E50–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz C, Juarez G, Munoz ML, Portnow J, Fineman I, Badie B, Mamelak A, Ferrell B. 2008. The quality of life of patients with malignant gliomas and their caregivers. Soc Work Health Care 47:455–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho NL, Moalem J, Chen L, Lubitz CC, Moore FD, Ruan DT. 2014. Surgeons and patients disagree on the potential consequences from hypoparathyroidism. Endocr Pract 20:427–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.