Abstract

The Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus) is of commercial importance, conservation concern, and is a representative of one of the oldest lineages of ray-finned fish, the Osteoglossomorpha. To add to genomic knowledge of this species and the evolution of teleosts, the genome of a Malaysian specimen of arowana was sequenced. A draft genome is presented consisting of 42,110 scaffolds with a total size of 708 Mb (2.85% gaps) representing 93.95% of core eukaryotic genes. Using a k-mer-based method, a genome size of 900 Mb was also estimated. We present an update on the phylogenomics of fishes based on a total of 27 species (23 fish species and 4 tetrapods) using 177 orthologous proteins (71,360 amino acid sites), which supports established relationships except that arowana is placed as the sister lineage to all teleost clades (Bayesian posterior probability 1.00, bootstrap replicate 93%), that evolved after the teleost genome duplication event rather than the eels (Elopomorpha). Evolutionary rates are highly heterogeneous across the tree with fishes represented by both slowly and rapidly evolving lineages. A total of 94 putative pigment genes were identified, providing the impetus for development of molecular markers associated with the spectacular colored phenotypes found within this species.

Keywords: genome, fish, phylogenomics, evolutionary rate, pigmentation genes

Introduction

More than half of all vertebrate species are fishes, with the Class Osteichthyes (bony fish) being the most diverse class within the Subphylum Vertebrata. (Santini et al. 2009; Near et al. 2012; Betancur-R et al. 2013). Fish have a long evolutionary history extending over 500 Myr into the Cambrian, with the evolution of the jawless fishes, which are currently represented by the lampreys (Agnatha). Jawed fishes (Gnathostoma) evolved some 450 Ma and are divided among three lineages: the cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes), the bony fishes (Osteichthyes), and the lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii). With the availability of more molecular genetic and genomic data, there has been increasing interest in understanding the diversification of the major fish groups and the molecular evolutionary dynamics of fish lineages, their timing, and evolution of specific genes (Inoue et al. 2003; Takezaki et al. 2004; Shan and Gras 2011; Near et al. 2012; Zou et al. 2012; Amemiya et al. 2013; Betancur-R et al. 2013; Broughton et al. 2013; Opazo et al. 2013; Dornburg et al. 2014; Venkatesh et al. 2014).

Of the 3 lineages in which fish are found, the bony fishes are by far the most diverse with nearly 30,000 recognized species and there has been much interest in understanding the drivers of their evolutionary success. Significant attention has been given to the impact of what is generally known as the fish- or teleost-specific genome duplication event (TGD) (Robinson-Rechavi et al. 2001; Hoegg et al. 2004; Hurley et al. 2005). Chromosomal duplications may provide opportunities for evolutionary experimentation, as paralogous genes are exapted to new functions, thereby facilitating rapid morphological, physiological, and behavioral diversification (Taylor et al. 2001; Hoegg et al. 2004; Meyer and Van de Peer 2005; Santini et al. 2009; Opazo et al. 2013).

The Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus: Osteoglossidae) is of fundamental interest to fish phylogenetics as it belongs to one of the oldest teleost groups, the Osteoglossomorpha. This lineage comprises the mooneyes, knifefish, elephantfish, freshwater butterflyfish, and bonytongues, and is one of the three ancient extant lineages that diverged immediately after the TGD. The other two are the Elopomorpha comprising eels, tarpons and bonefish, and the Clupeocephala, which embraces the majority of teleost diversity including the species-rich Ostariophysi (e.g., catfish, carps and minnows, tetras) and Percomorphaceae (e.g., wrasse, cichlids, gobies, flatfish) (Betancur-R et al. 2013; Broughton et al. 2013; Betancur-R, Naylor, et al. 2014; Betancur-R, Wiley, et al. 2014). There has been on-going disagreement on which one is the sister group to all other teleosts (Patterson and Rosen 1977; Nelson 1994; Arratia 1997; Patterson 1998; Zou et al. 2012). Historically, the Osteoglossomorph was considered to have diverged first (Patterson and Rosen 1977; Lauder and Liem 1983; Nelson 1994; Inoue et al. 2003; Brinkmann et al. 2004); however, comprehensive morphological studies, including both fossil and extant teleosts, and recent molecular-based studies supported the Elopomorpha as the sister lineage to all other bony fishes (Arratia 1997, 1999, 2000; Li and Wilson 1999; Diogo 2007; Santini et al. 2009; Near et al. 2012; Betancur-R et al. 2013; Broughton et al. 2013).

The arowana, sometimes also referred to as dragon fish, is also noteworthy as it is one of the most expensive fish in the world due to the occurrence of several bright color morphs that makes it highly sought after as an ornamental species (Dawes et al. 1999; Yue et al. 2006). Potentially relevant in this context is that teleost fishes are thought to have a greater range of pigment synthesis genes and pathways than any other vertebrate group (Braasch et al. 2009). However, the basis of color variation has seen little research in arowana with the exception of studies by Mohd-Shamsudin et al. (2011) and Mu et al. (2012) who found no consistent patterns of divergence between color variants and mitochondrial markers. Scleropages formosus is also of significant conservation concern in the wild. The species is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as endangered (Kottelat 2013) and by the Convention on International Trades in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora as “highly endangered” (Yue et al. 2006).

In this study, we present the whole genome sequences for S. formosus obtained from a captive Malaysian specimen, as a representative of the local wild form. We then place this species within a phylogenetic framework including sequences from all available fish with sequenced genomes making this the most complete phylogenomic analysis of fish so far conducted. We also carry out analysis of the rate of molecular evolution within and between fish lineages and identify a range of genes associated with pigmentation.

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

A total of 297,227,578 paired-end and 290,438,918 mate-pair reads (2 × 100 bp) were generated. Preprocessing resulted in 291,628,300 paired-end and 288,008,898 mate-pair reads, and these were subsequently assembled to generate a draft genome that consists of 42,110 scaffolds with a total size of 708 Mb and 2.85% gaps. The longest scaffold is 616,488 bp long and the N50 scaffold length is 58,849 bp. We also carried out a k-mer-based approach using read data and estimated the arowana genome size at approximately 900 Mb, a number in accord with the size of 1.05 Gb reported by Shen et al. (2014) estimated through flow cytometric comparative fluorescence with chicken cells. Based on these estimates, sequencing depth estimations ranging from 57 to 66 × coverage were inferred.

Features predicted from the assembly include 24,274 protein-coding genes, 609 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and 29 ribosomal RNAs (100% 5S rRNA). Based on sequence similarity (e-value threshold of 1 × 10−10, hit coverage cut-off of 70%), 71% of the predicted genes shared sequence similarity to another protein in the nonredundant (NR) database on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). For protein-coding genes, 95.8% have Annotation Edit Distance (Eilbeck et al. 2009) scores of less than 0.5 and 85.5% contain at least one Pfam domain, an indication of a well-annotated genome (Campbell et al. 2014).

The gene space in this assembly appears fairly complete with 93.95% of core eukaryotic genes represented. This is further supported by the mapping of 78.92% of transcriptomic reads sequenced from a different arowana sample from Shen et al. (2014) to our assembled genome, with 64.32% of unmapped reads belonging to 18S and 28S ribosomal genes and 7.60% to mitochondrial genes. These genes are usually present in high copy numbers and may not have been assembled in our de novo assembly due to exceedingly high read coverage and short read lengths (Nagarajan and Pop 2013). This finding is also consistent with the lack of specific rRNAs (18S, 28S) predicted from the assembly.

Phylogenomics and Evolutionary Rates

Our sample of arowana shows a 100% identity to the most common mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) haplotype (accession number: HM156394) found among Malaysian specimens by Mohd-Shamsudin et al. (2011) and is 99.87% similar to the complete COI gene (accession number: DQ023143) from a fish obtained from a commercial farm in Singapore (Yue et al. 2006). Tree-based ortholog inference resulted in a set of orthologous proteins belonging to 177 gene families (supplementary material S1, Supplementary Material online) shared across all 23 fishes and 4 tetrapod species (table 1). Concatenation of each aligned ortholog generated a final supermatrix comprising of a total of 71,360 amino acid sites per species with only 7.07% gaps. The aligned supermatrix and the best-fit partitioning scheme generated by PartitionFinder can be found in supplementary materials S2 and S3, Supplementary Material online. Rooted with the Chondrichthyes, both Bayesian (BI) and maximum-likelihood (ML) inferred phylogenomic trees display a topology largely consistent with recent studies with either more limited taxon sampling (Zou et al. 2012; Amemiya et al. 2013) or smaller gene sampling (Broughton et al. 2013; Glasauer and Neuhauss 2014; Braasch et al. 2015) with respect to evolutionary relationships and taxonomic classification (fig. 1).

Table 1.

List of Species Included in the Phylogenetic Analyses

| Organismsource | Scientific Name | Class | Order | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ray-finned fish | ||||

| Asian arowana* | Scleropages formosus | Actinopterygii | Osteoglossiformes | This study |

| European eelZ | Anguilla anguilla | Actinopterygii | Anguilliformes | Henkel et al. (2012) |

| MedakaE | Oryzias latipes | Actinopterygii | Beloniformes | Kasahara et al. (2007) |

| Blind cave fishE | Astyanax mexicanus | Actinopterygii | Characiformes | McGaugh et al. (2014) |

| Common carpC | Cyprinus carpio | Actinopterygii | Cypriniformes | Xu et al. (2014) |

| ZebrafishE | Danio rerio | Actinopterygii | Cypriniformes | Howe et al. (2013) |

| Amazon mollyE | Poecilia formosa | Actinopterygii | Cyprinodontiformes | Unpublished |

| Southern platyfishE | Xiphophorus maculatus | Actinopterygii | Cyprinodontiformes | Schartl et al. (2013) |

| Northern pikeV | Esox lucius | Actinopterygii | Esociformes | Rondeau et al. (2014) |

| Atlantic codE | Gadus morhua | Actinopterygii | Gadiformes | Star et al. (2011) |

| Three-spined sticklebackE | Gasterosteus aculeatus | Actinopterygii | Gasterosteiformes | Jones et al. (2012) |

| Electric eelF | Electrophorus electricus | Actinopterygii | Gymnotiformes | Gallant et al. (2014) |

| Spotted garE | Lepisosteus oculatus | Actinopterygii | Lepisosteiformes | Unpublished |

| Nile tilapiaE | Oreochromis niloticus | Actinopterygii | Perciformes | Brawand et al. (2014) |

| Atlantic salmonSA | Salmo salar | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Davidson et al. (2010) |

| Rainbow troutG | Oncorhynchus mykiss | Actinopterygii | Salmoniformes | Berthelot et al. (2014) |

| Japanese pufferE | Takifugu rubripes | Actinopterygii | Tetraodontiformes | Aparicio et al. (2002) |

| Green spotted pufferE | Tetraodon nigroviridis | Actinopterygii | Tetraodontiformes | Jaillon et al. (2004) |

| Lobe-finned fish | ||||

| African coelacanthE | Latimeria chalumnae | Sarcopterygii | Coelacanthiformes | Amemiya et al. (2013) |

| aLungfishSR | Protopterus annectens | Sarcopterygii | Lepidosireniformes | Amemiya et al. (2013) |

| Cartilaginous fish | ||||

| Elephant sharkA | Callorhinchus milii | Chondrichthyes | Chimaeriformes | Venkatesh et al. (2014) |

| bSmall-spotted catsharkSK | Scyliorhinus canicula | Chondrichthyes | Carchariniformes | Wyffels et al. (2014) |

| bLittle skateSK | Leucoraja erinacea | Chondrichthyes | Rajiformes | Wang et al. (2012) |

| Tetrapods | ||||

| Western clawed frogE | Xenopus tropicalis | Amphibia | Anura | Fuchs et al. (2006) |

| ChickenE | Gallus gallus | Aves | Galliformes | Hillier et al. (2004) |

| HumanE | Homo sapiens | Mammalia | Primates | Venter et al. (2001) |

| LizardE | Anolis carolinensis | Reptilia | Squamata | Alföldi et al. (2011) |

Note.—Codes for source: A*STAR (A), CarpBase (C), Ensembl (E), efish genomics (F), Genoscope (G), SalmonDB (SA), SkateBase (SK), SRA (SR), UVic (V), ZF Genomics (Z), this study (*).

aRaw transcriptome reads were used.

bAssembled transcripts were used.

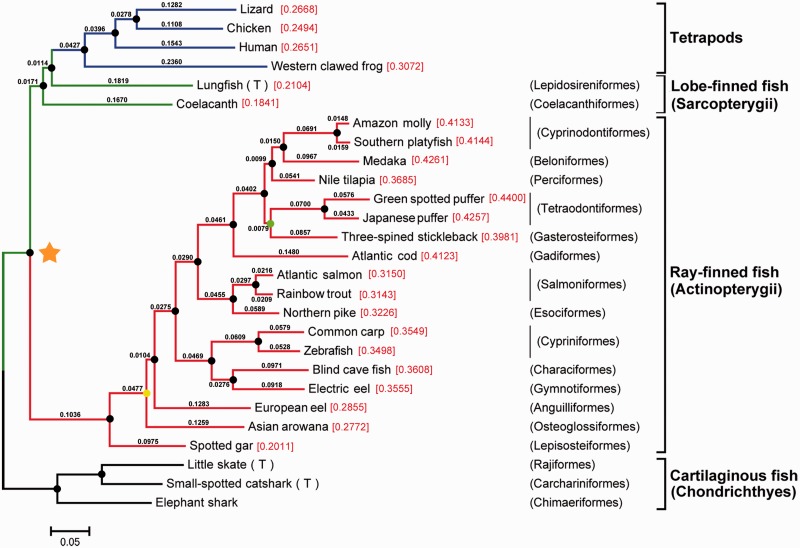

Fig. 1.—

Phylogenetic relationships among fish species. The phylogenetic tree was inferred from a supermatrix containing the alignment of sequences from 27 species (177 orthologous proteins, 71,360 aligned amino acid positions, 7.07% gaps) and was rooted with the Chondrichthyes. Black circles indicate maximum nodal support with bootstrap values of 100% and Bayesian posterior probabilities of 1.00. The yellow and green circles represent 93% and 98% bootstrap support values, respectively, both with maximal Bayesian posterior probability values of 1.00. Branch length information is included and the rate of molecular evolution (number of amino acid substitutions per site) for each fish lineage is placed beside each taxa label. These values were calculated from the split of all ray-finned fish from lobe-finned fish and tetrapod lineages (node indicated with the orange star). A (T) is placed next to the species for which transcriptome data were utilized.

The rapid and divergent evolution of certain ray-finned fish groups is apparent in the tree from the relatively long branch lengths. Substantial evolutionary rate heterogeneity is observed within and among fish lineages by the comparison of amino acid substitutions per site calculated from branch lengths (fig. 1). Furthermore, based on Tajima’s relative rate test (supplementary material S4, Supplementary Material online), the Asian arowana was reported to have a significantly different evolutionary rate in comparison with other ray-finned fish lineages with P values ranging from 0 to 0.00048 (European eel). Using a Bonferroni corrected critical P value of 0.00098 (equivalent to α = 0.05 for a single test) results in the rejection of null hypothesis of equal rates of evolution between the arowana lineages and all other fish species.

A major difference in our estimated phylogenetic relationships to other recent studies is the placement of the arowana sample as the sister lineage to all other teleost lineages, which conflicts with morphology-based studies and more recent molecular perspectives which posit that Elopomorpha is the sister group to all other teleost lineages (Arratia 1997, 1999; Li and Wilson 1999; Diogo 2007; Broughton et al. 2013; Glasauer and Neuhauss 2014). However, our result is consistent with other studies that have the Osteoglossomorpha as the sister lineage to all other teleosts (Patterson and Rosen 1977; Lauder and Liem 1983; Nelson 1994; Inoue et al. 2003; Brinkmann et al. 2004). We look forward to more comprehensive genomic resources becoming available with greater taxon sampling for teleost fishes to allow more rigorous testing of these alternate hypotheses.

Our results support the findings of Amemiya et al. (2013) who found that the lungfish and not the coelacanth to be the closest relative to the tetrapods, which has also been a subject to much disputation (Brinkmann et al. 2004; Takezaki et al. 2004; Shan and Gras 2011). However, although we also found that the coelacanth proteins evolve at a slower rate relative to those of the tetrapods, from figure 1 it can be seen that the substitution rate in the coelacanth lineage is more than half of that for the tetrapod lineage, which is substantially faster than that observed by Amemiya et al. (2013). This discrepancy is most likely a result of the use of different protein data sets, taxon sampling, and outgroups in the two studies and provides a caveat for generalizing results from a single study even when utilizing information from a large number of genes.

Putative Pigmentation Genes

A total of 94 different pigmentation genes were identified from our genome sequences (table 2). Only the best hit for each pigmentation gene was retained in the table and these are grouped into various functional categories related to melanophore development, components of melanosomes, melanosome construction, melanosome transport, regulation of melanogenesis, systemic effects, xanthophore development, pteridine synthesis, iridophore development, and other functions as shown by Braasch et al. (2009). This result indicates that a wide range of pigmentation genes have been retained across the teleosts and will provide a valuable resource for the study of the genetic and developmental basis for the spectacular color phenotypes of the Asian arowana.

Table 2.

Putative Arowana Pigmentation Genes

| Gene | Accession (Homo sapiens) | Locus ID (arowana) | PID | e-value | Accession (annotation) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanophore development | ||||||

| adam17 | NP_003174.3 | Z043_115716 | 68.98 | 0.00 | XP_010733184.1 | Larimichthys crocea |

| adamts20 | NP_079279.3 | Z043_106475 | 71.36 | 0.00 | XP_008274326.1 | Stegastes partitus |

| creb1 | NP_004370.1 | Z043_122987 | 95.37 | 0.00 | XP_005167757.1 | Danio rerio |

| ece1 | NP_001106819.1 | Z043_112628 | 80.03 | 0.00 | CDQ77702.1 | Oncorhynchus mykiss |

| Ednrb | NP_001116131.1 | Z043_105076 | 81.50 | 0.00 | XP_007254865.1 | Astyanax mexicanus |

| Egfr | NP_958439.1 | Z043_114891 | — | — | — | — |

| fgfr2 | NP_000132.3 | Z043_104866 | 84.50 | 0.00 | KKF10433.1 | La. crocea |

| frem2 | NP_997244.4 | Z043_101382 | 70.22 | 0.00 | XP_012683949.1 | Clupea harengus |

| fzd4 | NP_036325.2 | Z043_108755 | 89.76 | 0.00 | XP_012693402.1 | Cl. harengus |

| gna11 | NP_002058.2 | Z043_106310 | 96.02 | 0.00 | XP_010750457.1 | La. crocea |

| gnaq | NP_002063.2 | Z043_114081 | 86.57 | 0.00 | XP_010735114.1 | La. crocea |

| gpc3 | NP_001158091.1 | Z043_101235 | 52.03 | 3 × 10−175 | XP_006639062.1 | Lepisosteus oculatus |

| gpr161 | NP_722561.1 | Z043_116750 | 73.06 | 0.00 | XP_007227875.1 | As. mexicanus |

| hdac1 | NP_004955.2 | Z043_108210 | 96.71 | 0.00 | XP_006631299.1 | Le. oculatus |

| ikbkg | NP_003630.1 | Z043_105761 | 64.16 | 2 × 10−170 | XP_010903123.1 | Esox lucius |

| itgb1 | NP_596867.1 | Z043_116749 | 71.96 | 0.00 | NP_001030143.1 | D. rerio |

| Kit | NP_001087241.1 | Z043_118854 | 71.89 | 0.00 | XP_008297546.1 | St. partitus |

| lef1 | NP_057353.1 | Z043_100731 | — | — | — | — |

| lmx1a | NP_001167540.1 | Z043_108871 | 91.03 | 9 × 10−180 | XP_008417499.1 | Poecilia reticulata |

| mbtps1 | NP_003782.1 | Z043_104391 | 86.31 | 0.00 | XP_009291810.1 | D. rerio |

| mcoln3 | NP_060768.8 | Z043_110213 | 69.96 | 0.00 | XP_006634884.1 | Le. oculatus |

| mitf | NP_937801.1 | Z043_105357 | 83.91 | 0.00 | XP_006630679.1 | Le. oculatus |

| pax3 | NP_039230.1 | Z043_107599 | — | — | — | — |

| rab32 | NP_006825.1 | Z043_104281 | 78.47 | 6 × 10−118 | XP_012671987.1 | Cl. harengus |

| scarb2 | NP_005497.1 | Z043_105397 | 78.22 | 0.00 | NP_001117983.1 | O. mykiss |

| sfxn1 | NP_073591.2 | Z043_121119 | 89.10 | 0.00 | XP_010895582.1 | E. lucius |

| snai2 | NP_003059.1 | Z043_117231 | 85.88 | 5 × 10−164 | XP_003759837.1 | Sarcophilus harrisii |

| sox10 | NP_008872.1 | Z043_106242 | 77.78 | 0.00 | XP_008294581.1 | St. partitus |

| sox18 | NP_060889.1 | Z043_107469 | 61.33 | 3 × 10−161 | XP_001337702.1 | D. rerio |

| sox9 | NP_000337.1 | Z043_118917 | 79.08 | 0.00 | XP_006635207.1 | Le. oculatus |

| tfap2a | NP_001027451.1 | Z043_119933 | 86.12 | 0.00 | XP_006634534.1 | Le. oculatus |

| trpm1 | NP_001238949.1 | Z043_111666 | 71.06 | 0.00 | XP_006629107.1 | Le. oculatus |

| trpm7 | NP_060142.3 | Z043_100441 | 82.16 | 0.00 | XP_006628750.1 | Le. oculatus |

| wnt1 | NP_005421.1 | Z043_120129 | 93.51 | 0.00 | XP_010873444.1 | E. lucius |

| wnt3a | NP_149122.1 | Z043_118184 | 96.12 | 0.00 | XP_008312650.1 | Cynoglossus semilaevis |

| zic2 | NP_009060.2 | Z043_101779 | 88.54 | 0.00 | XP_006638968.1 | Le. oculatus |

| Components of melanosomes | ||||||

| dct | NP_001913.2 | Z043_108526 | 73.9 | 0.00 | XP_008326759.1 | Cy. semilaevis |

| rab32 | NP_006825.1 | Z043_116536 | 67.76 | 1 × 10−88 | XP_003224067.2 | Anolis carolinensis |

| rab38 | NP_071732.1 | Z043_122112 | 90.05 | 1 × 10−126 | AAI50366.1 | D. rerio |

| slc24a4 | NP_705934.1 | Z043_114251 | 81.84 | 0.00 | XP_005803162.1 | Xiphophorus maculatus |

| slc24a5 | NP_995322.1 | Z043_103396 | 82.06 | 0.00 | XP_005814818.1 | X. maculatus |

| tyrp1 | NP_000541.1 | Z043_107956 | 74.52 | 0.00 | XP_005743086.1 | Pundamilia nyererei |

| Melanosome construction | ||||||

| ap3d1 | NP_003929.4 | Z043_120762 | 73.21 | 0.00 | XP_011472829.1 | Oryzias latipes |

| fig4 | NP_055660.1 | Z043_103115 | 86.55 | 0.00 | XP_006626354.1 | Le. oculatus |

| gpr143 | NP_000264.2 | Z043_102175 | 78.42 | 0.00 | XP_012680526.1 | Cl. harengus |

| hps3 | NP_115759.2 | Z043_100370 | 70.79 | 0.00 | XP_012680760.1 | Cl. harengus |

| lyst | NP_001288294.1 | Z043_100757 | 69.99 | 0.00 | XP_008300589.1 | St. partitus |

| nsf | NP_006169.2 | Z043_108447 | 93.61 | 0.00 | XP_005164054.1 | D. rerio |

| pldn | NP_036520.1 | Z043_109414 | 78.42 | 4 × 10−73 | XP_008274283.1 | St. partitus |

| rabggta | NP_004572.3 | Z043_121567 | — | — | — | — |

| txndc5 | NP_110437.2 | Z043_116626 | 77.02 | 0.00 | CDQ77189.1 | O. mykiss |

| vps11 | NP_068375.3 | Z043_121081 | 90.41 | 0.00 | XP_010863485.1 | E. lucius |

| vps18 | NP_065908.1 | Z043_111267 | 85.09 | 0.00 | XP_010892538.1 | E. lucius |

| vps33a | NP_075067.2 | Z043_116542 | 94.66 | 0.00 | CDQ76904.1 | O. mykiss |

| vps39 | NP_056104.2 | Z043_117047 | 89.05 | 0.00 | XP_010749485.1 | La. crocea |

| Melanosome transport | ||||||

| mlph | NP_077006.1 | Z043_101687 | 62.90 | 0.00 | XP_005168768.1 | D. rerio |

| myo5a | NP_000250.3 | Z043_102448 | 86.24 | 0.00 | XP_006628770.1 | Le. oculatus |

| myo7a | NP_001120652.1 | Z043_100931 | 78.91 | 0.00 | AAI63570.1 | D. rerio |

| rab27a | NP_899059.1 | Z043_111973 | 87.89 | 2 × 10−148 | XP_006628775.1 | Le. oculatus |

| Regulation of melanogenesis | ||||||

| creb1 | NP_004370.1 | Z043_122987 | 95.37 | 0.00 | XP_005167757.1 | D. rerio |

| drd2 | NP_000786.1 | Z043_112980 | 83.67 | 0.00 | XP_006642348.1 | Le. oculatus |

| mc1r | NP_002377.4 | Z043_121636 | 76.15 | 4 × 10−167 | AGC50885.1 | Cyprinus carpio |

| mgrn1 | NP_001135763.2 | Z043_111249 | 85.27 | 0.00 | XP_006637253.1 | Le. oculatus |

| pomc | NP_001030333.1 | Z043_103340 | 51.72 | 7 × 10−66 | AAO17793.1 | Anguilla japonica |

| Systemic effects | ||||||

| atp6ap1 | NP_001174.2 | Z043_108102 | 66.24 | 0.00 | XP_012682891.1 | Cl. harengus |

| atp6ap2 | NP_005756.2 | Z043_100882 | 75.14 | 0.00 | XP_012675204.1 | Cl. harengus |

| atp6v0c | NP_001185498.1 | Z043_125122 | 95.36 | 3 × 10−90 | XP_008434615.1 | P. reticulata |

| atp6v0d1 | NP_004682.2 | Z043_121933 | 94.48 | 0.00 | NP_955914.1 | D. rerio |

| atp6v1e1 | NP_001687.1 | Z043_104549 | 92.09 | 2 × 10−143 | XP_007579195.1 | Poecilia formosa |

| atp6v1f | NP_004222.2 | Z043_100808 | 100.00 | 4 × 10−81 | XP_006633325.1 | Le. oculatus |

| atp6v1h | NP_998784.1 | Z043_113483 | 90.61 | 0.00 | XP_007260238.1 | As. mexicanus |

| atp7b | NP_000044.2 | Z043_122088 | 54.41 | 0.00 | XP_010017200.1 | Nestor notabilis |

| rps19 | NP_001013.1 | Z043_118939 | 91.67 | 7 × 10−95 | XP_008329573.1 | Cy. semilaevis |

| rps20 | NP_001014.1 | Z043_107890 | 100.00 | 4 × 10−80 | NP_001117836.1 | O. mykiss |

| Xanthophore development | ||||||

| atp6v1e1 | NP_001687.1 | Z043_104549 | 92.09 | 2 × 10−143 | XP_007579195.1 | P. formosa |

| atp6v1h | NP_998784.1 | Z043_113483 | 90.61 | 0.00 | XP_007260238.1 | As. mexicanus |

| csf1r | NP_001275634.1 | Z043_118854 | 71.89 | 0.00 | XP_008297546.1 | St. partitus |

| ednrb | NP_001116131.1 | Z043_105076 | 81.50 | 0.00 | XP_007254865.1 | As. mexicanus |

| ghr | NP_001229389.1 | Z043_101160 | 57.24 | 0.00 | BAD20706.1 | An. japonica |

| pax3 | NP_039230.1 | Z043_107599 | — | — | — | — |

| sox10 | NP_008872.1 | Z043_106242 | 77.78 | 0.00 | XP_008294581.1 | St. partitus |

| Pteridine synthesis | ||||||

| gchi | NP_001019195.1 | Z043_110449 | 81.94 | 1 × 10−125 | XP_007231033.1 | As. mexicanus |

| mycbp2 | NP_055872.4 | Z043_104473 | 91.14 | 0.00 | XP_007251746.1 | As. mexicanus |

| paics | NP_001072992.1 | Z043_121868 | 87.94 | 0.00 | XP_010870568.1 | E. lucius |

| pcbd1 | NP_000272.1 | Z043_105842 | 95.05 | 1 × 10−66 | XP_012672435.1 | Cl. harengus |

| Pts | NP_000308.1 | Z043_103015 | 81.21 | 2 × 10−84 | XP_012670027.1 | Cl. harengus |

| qdpr | NP_000311.2 | Z043_109962 | 86.83 | 5 × 10−129 | XP_006137052.1 | Pelodiscus sinensis |

| Spr | NP_003115.1 | Z043_114288 | 63.64 | 6 × 10−126 | NP_001133746.1 | Salmo salar |

| xdh | NP_000370.2 | Z043_115384 | 69.12 | 0.00 | XP_006636840.1 | Le. oculatus |

| Iridophore development | ||||||

| atp6v1h | NP_998784.1 | Z043_113483 | 90.61 | 0.00 | XP_007260238.1 | As. mexicanus |

| dac | NP_001077.2 | Z043_123292 | 73.28 | 0.00 | ACN11084.1 | Sa. salar |

| ednrb | NP_001116131.1 | Z043_105076 | 81.50 | 0.00 | XP_007254865.1 | As. mexicanus |

| Ltk | NP_002335.2 | Z043_118424 | 68.81 | 0.00 | XP_010877407.1 | E. lucius |

| sox10 | NP_008872.1 | Z043_106242 | 77.78 | 0.00 | XP_008294581.1 | St. partitus |

| sox9 | NP_000337.1 | Z043_118917 | 79.08 | 0.00 | XP_006635207.1 | Le. oculatus |

| trim33 | NP_056990.3 | Z043_115609 | 66.93 | 0.00 | NP_001002871.2 | D. rerio |

| vps18 | NP_065908.1 | Z043_111267 | 85.09 | 0.00 | XP_010892538.1 | E. lucius |

| vps39 | NP_056104.2 | Z043_117047 | 89.05 | 0.00 | XP_010749485.1 | La. crocea |

| Uncategorized function | ||||||

| abhd11 | NP_683711.1 | Z043_117262 | 79.64 | 9 × 10−155 | XP_010893523.1 | E. lucius |

| ebna1bp2 | NP_006815.2 | Z043_123300 | 77.78 | 7 × 10−146 | XP_006634973.1 | Le. oculatus |

| gfpt1 | NP_002047.2 | Z043_101574 | 95.16 | 0.00 | XP_006625541.1 | Le. oculatus |

| gja5 | NP_859054.1 | Z043_107343 | 71.02 | 0.00 | XP_008273833.1 | St. partitus |

| irf4 | NP_002451.2 | Z043_102759 | 75.71 | 0.00 | XP_006634623.1 | Le. oculatus |

| kcnj13 | NP_002233.2 | Z043_119194 | 71.76 | 7 × 10−173 | XP_010768290.1 | Notothenia coriiceps |

| pabpc1 | NP_002559.2 | Z043_109572 | 96.20 | 0.00 | XP_007230879.1 | As. mexicanus |

| skiv2l2 | NP_056175.3 | Z043_112154 | 91.68 | 0.00 | XP_006627067.1 | Le. oculatus |

| tpcn2 | NP_620714.2 | Z043_115041 | 62.50 | 0.00 | CDQ78014.1 | O. mykiss |

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

A tail fin sample of S. formosus from a specimen was donated by the Malaysian Freshwater Fisheries Research Centre (FRI Glami Lemi). DNA was extracted using Qiagen Blood and Tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 1 µg of the purified DNA was sheared (500 bp setting) using Covaris S220 (Covaris, Woburn, MA) and prepped with Illumina TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Additionally, a 3-kb insert mate-pair library was generated using the Illumina Mate Pair Library Prep Kit. Both libraries were quantified using KAPA library quantification kit (KAPA Biosystems, Capetown, South Africa) and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 using the 2 × 101 bp paired-end read setting (Illumina) located at the Malaysian Genomics Resource Centre.

Genome Size Estimation based on k-mer Frequency in Sequence Reads

Genome size of S. formosus was approximated from k-mer frequency distributions in raw genomic reads as was done by Li et al. (2010). Frequencies of distinct 15-, 17-, 19-, and 21-mers occurring in genomic reads from the paired-end library were counted using JELLYFISH (Marçais and Kingsford 2011). The real sequencing depth (N) was estimated from the peak of each frequency distribution (M), read length (L), and k-mer length (K) correlated according to the following formula: M = N × (L − K + 1)/L. Genome size was then approximated from the division of total genomic bases by the real sequencing depth.

Assembly and Annotation of the Scleropages formosus Genome

Raw reads were error corrected and preprocessed by removing low-quality reads (average Phred quality ≤20) and reads containing more than 10% ambiguous nucleotides. The resulting set of reads longer than 30 bp were assembled and scaffolded using the MSR-CA genome assembler (now renamed MaSuRCA, with default settings) (Zimin et al. 2013). Further scaffolding was carried out with reads from the mate-pair library using Scaffolder (Barton MD and Barton HA 2012). The final draft assembly consists of scaffolds longer than 200 bp. Finally, the CEGMA program (Parra et al. 2007) was used to assess the completeness of the assembly by detecting the presence of 248 highly conserved proteins within the draft genome. To compare our draft assembly with other arowana resources, transcriptomic reads generated using 454 pyrosequencing from the Asian arowana transcriptome (Shen et al. 2014) were aligned to the draft genome using GMAP (Wu and Watanabe 2005). Unmapped transcriptomic reads were further characterized by a BLASTN (Altschul et al. 1990) search against the NT database on NCBI.

Arowana transcriptome reads were downloaded (SRA: SRR941557, SRR941783, SRR941785), preprocessed with QTrim (default settings) (Shrestha et al. 2014), and assembled de novo using IDBA-tran (–max_isoforms 10 –maxk 80) (Peng et al. 2013). To predict protein-coding genes, MAKER (Cantarel et al. 2008) was run on the arowana genome using the assembled arowana transcriptome and Ensembl proteins from zebrafish (Danio rerio), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), medaka (Oryzias latipes), and Japanese puffer (Takifugu rubripes) as evidence. Repetitive regions were masked with all organisms in RepBase. MAKER was run iteratively to train the SNAP (Korf 2004) gene predictor in a bootstrap fashion to improve the predictor’s performance, and final MAKER predictions were made using the trained SNAP as well as Augustus trained with the zebrafish species model. Functional annotation of the predicted sequences was performed with a BLASTP (Altschul et al. 1990) search (e-value threshold of 1 × 10−10) against vertebrate proteins in NCBI’s NR database. A 70% blast hit coverage cut-off (based on subject length) was also applied to obtain confident annotations. Unannotated protein sequences were then searched against all sequences in NCBI’s NR database with the same e-value and hit coverage cut-offs. Gene ontologies, protein domains, and families were identified with InterProScan (Jones et al. 2014). tRNA genes in the assembly were detected by MAKER using tRNAscan (Lowe and Eddy 1997), while RNAmmer (Lagesen et al. 2007) was used to predict rRNA sequences.

Orthology Inference

Data selection for phylogenomic analyses is controversial and centers on issues of data quality and quantity and on benefits of taxon sampling versus high data coverage that minimizes alignment gaps (Laurin-Lemay et al. 2012; Amemiya et al. 2013; Betancur-R et al. 2013; Misof et al. 2013; Salichos and Rokas 2013). We take a conservative approach that minimizes gaps in the supermatrix and use several ways to carefully distinguish orthologs from paralogs to assemble a high quality phylogenomic data set, ensuring the estimation of a robust and accurate tree, including the placement of the deeper lineages in the tree.

First, because conserved genes make for the best phylogenomic markers (Betancur-R et al. 2013), Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles from the TreeFam database (Schreiber et al. 2014) of gene families conserved across 104 other animal species were used to identify these conserved protein sequences in the arowana genome. For all species, protein sequences longer than 100 amino acids were scanned for sequence homology to gene families in the TreeFam database (version 9) (Schreiber et al. 2014) using hmmsearch (Eddy 2011) (e-value threshold of 1 × 10−10) and gene families having sequence homology to at least one protein in all 27 species were retained for subsequent orthology inference. Orthology inference from these protein clusters was conducted with scripts from the pipeline recently described by Yang and Smith (2014), which employs a tree-based approach to first identify paralogs, prune spurious branches, and finally identify orthologs. Briefly, protein sequences in each gene family were aligned and trimmed with the fasta_to_tree.py script. In addition, clusters containing paralogs were limited during orthology inference by implementing a tree-based approach on individual sequence clusters, along with additional pruning steps, to separate paralogs and orthologs (Yang and Smith 2014). Due to computational limitations, we modified the pipeline to use IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al. 2015) to build smaller gene trees (less than 1,000 sequences) and FastTreeMP (Price et al. 2010) for larger gene trees. For each tree, tips longer than 0.5 (=absolute tip cut-off) or longer than 0.2 and ten times longer than its nearby tips (=relative tip cut-off) were trimmed with trim_tips.py. Monophyletic tips belonging to the same taxon were masked with mask_tips_by_taxonID_genomes.py. Internal branches longer than 0.3, which may be separating orthologous groups, were cut with cut_long_internal_branches.py and only trees containing sequences from all 27 species were retained, thus reducing the amount of missing data and lowering the potential for nonphylogenetic signals (Borowiec et al. 2015). Protein sequence alignment, alignment trimming, and gene tree building were repeated for remaining sequences for each tree. Orthology inference was then carried out on the newly inferred trees with paralogy pruning by maximum inclusion using the prune_paralogy_MI.py script (relative tip cut-off 0.2, absolute tip cut-off 0.5, minimum taxa 27), which iteratively extracts the subtree containing the most taxa without taxon duplication. Protein sequences in each cluster were aligned with mafft_wrapper.py, each alignment was trimmed with pep_gblocks_wrapper.py, and all alignments were finally concatenated into a supermatrix.

Orthology calls in teleosts, and specifically for Osteoglossomorphs and Elopomorphs, are not as simple and are complicated by divergent evolution in genes as a result of multiple rounds of genome duplication prior to teleost diversification (Braasch et al. 2015). Although we have taken several strict measures to identify orthologs and exclude paralogs, it is important to note that it is extremely challenging to ensure that all identified protein sequences in each cluster are truly orthologous.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was done based on amino acid alignments for a total of 27 species (table 1). For organisms lacking available proteome data sets, namely the lungfish, little skate, and small-spotted catshark, protein sequences were obtained from their respective transcriptomes. For the lungfish specifically, raw Illumina RNA-seq reads (SRA: SRR505721–SRR505726) were assembled with the Trinity assembler (Grabherr et al. 2011). All transcriptomes were translated with Transdecoder (http://transdecoder.sourceforge.net/, last accessed April 14, 2015).

Each ortholog is treated as a separate data block and used as input to PartitionFinder (branchlengths = linked, model_selection = AICc, search = rcluster) (Lanfear et al. 2014) to estimate the best-fit partitioning schemes and models of protein evolution. Based on these results, ML analysis was conducted with RAxML (Stamatakis 2014) under the recommended partitions and substitution models. A total of 100 trees were generated using distinct random seeds and the tree with the best likelihood value was chosen as the final tree topology. Nodal support was represented by bootstrap replicates with the autoMRE convergence criterion (Pattengale et al. 2009). A Bayesian inference using the same supermatrix partitioned into each ortholog was also carried out using ExaBayes (Aberer et al. 2014). Four independent chains were run for 2 million generations and sampled every 500 generations. With 25% of initial samples discarded as burn-in, runs were considered to have converged when the average standard deviation of split frequencies is less than 1%. Both ML and BI phylogenetic trees were rooted using the Chondrichthyes as the outgroup and visualized with MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2013).

Rate of Molecular Evolution

To compare evolutionary rates of the Asian arowana versus other ray-finned fish lineages, the rate of molecular evolution for each fish lineage was calculated by adding branch lengths from the end of each terminal branch to the node where the split between ray-finned fish and lobe-finned fish (and tetrapods) occurred (fig. 1, orange star). In addition, the Tajima’s relative rate test (Tajima 1993) was implemented, as done by Amemiya et al. (2013) to test for equal rates between lineages. Using MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2013), Tajima’s relative rate tests (with missing positions and gaps eliminated) were conducted for comparisons between the Asian arowana and other ray-finned fishes, with a member of the Chondricthyes set as outgroup.

Identification of Putative Pigmentation Genes

Predicted protein sequences for arowana were screened for putative pigmentation genes using a list curated by Braasch et al. (2009). Using their homologs in humans (table 2), arowana proteins were searched against pigment genes using BLASTP (Altschul et al. 1990) with an e-value threshold of 1 × 10−40 and subsequently filtered with a hit coverage cut-off of 70%. The best hit for each pigment gene was chosen as a candidate to test for the presence of conserved domains by using the Batch CD-Search tool (Marchler-Bauer and Bryant 2004) to search against the Conserved Domain Database (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials S1–S4 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgment

Funding for this study was provided by the Monash University Malaysia Tropical Medicine and Biology Multidisciplinary Platform. We are also grateful to the staff of the Malaysian Freshwater Fisheries Research Centre (FRI Glami Lemi), Jelebu, and Puviarasi Meganathan, Monash University Malaysia, for their assistance. We particularly thank Broad Institute for their permission to use the spotted gar genomic resources in this work and also acknowledge Wesley Warren and The Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine, for the availability of the Amazon molly genome.

Literature Cited

- Aberer AJ, Kobert K, Stamatakis A. 2014. ExaBayes: massively parallel bayesian tree inference for the whole-genome era. Mol Biol Evol. 31:2553–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alföldi J, et al. 2011. The genome of the green anole lizard and a comparative analysis with birds and mammals. Nature 477:587–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya CT, et al. 2013. The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature 496:311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio S, et al. 2002. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science 297:1301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arratia G. 1997. Basal teleosts and teleostean phylogeny. Palaeo Ichthyologica 7:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Arratia G. 1999. The monophyly of Teleostei and stem-group teleosts. Consensus and disagreements. In: Arratia G, Schultze HP, editors. Mesozoic fishes 2—systematics and the fossil record. Munich (Germany): Friedrich Pfeil; p. 265–334. [Google Scholar]

- Arratia G. 2000. Phylogenetic relationships of Teleostei. Past and present. Estud Oceanol. 19:19–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barton MD, Barton HA. 2012. Scaffolder—software for manual genome scaffolding. Source Code Biol Med. 7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot C, et al. 2014. The rainbow trout genome provides novel insights into evolution after whole-genome duplication in vertebrates. Nat Commun. 5:3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur-R R, Naylor GJ, Ortí G. 2014. Conserved genes, sampling error, and phylogenomic inference. Syst Biol. 63:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentancur-R R, Wiley E, et al. 2014 Phylogenetic classification of bony fishes—version 3. Available from: http://www.deepfin.org/Classification_v3.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Betancur-R R, et al. 2013. The tree of life and a new classification of bony fishes. PLoS Curr: Tree of Life. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiec ML, Lee EK, Chiu JC, Plachetzki DC. 2015. Dissecting phylogenetic signal and accounting for bias in whole-genome data sets: a case study of the Metazoa. bioRxiv Advance Access published January 16, 2015; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/013946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I, Brunet F, Volff JN, Schartl M. 2009. Pigmentation pathway evolution after whole-genome duplication in fish. Genome Biol Evol. 1:479–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I, et al. 2015. A new model army: emerging fish models to study the genomics of vertebrate Evo-Devo. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 324:316–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawand D, et al. 2014. The genomic substrate for adaptive radiation in African cichlid fish. Nature 513:375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann H, Venkatesh B, Brenner S, Meyer A. 2004. Nuclear protein-coding genes support lungfish and not the coelacanth as the closest living relatives of land vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101:4900–4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton RE, Betancur-R R, Li C, Arratia G, Ortí G. 2013. Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis reveals the pattern and tempo of bony fish evolution. PLoS Curr. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MS, Holt C, Moore B, Yandell M. 2014. Genome annotation and curation using MAKER and MAKER-P. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 48:4.11.1–4.11.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, et al. 2008. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18:188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, et al. 2010. Sequencing the genome of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Genome Biol. 11:403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes JA, Lim LC, Cheong L. 1999. The dragon fish. England: Kingdom Books. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R. 2007. The origin of higher clades: osteology, myology, phylogeny and evolution of bony fishes and the rise of tetrapods. Science Pub Incorporated. New Hamsphire: Enfield. [Google Scholar]

- Dornburg A, Townsend JP, Friedman M, Near TJ. 2014. Phylogenetic informativeness reconciles ray-finned fish molecular divergence times. BMC Evol Biol. 14:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. 2011. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 7:e1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilbeck K, Moore B, Holt C, Yandell M. 2009. Quantitative measures for the management and comparison of annotated genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 10:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C, Burmester T, Hankeln T. 2006. The amphibian globin gene repertoire as revealed by the Xenopus genome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 112:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JR, et al. 2014. Genomic basis for the convergent evolution of electric organs. Science 344:1522–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasauer SMK, Neuhauss SCF. 2014. Whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes and its evolutionary consequences. Mol Genet Genomics. 289:1045–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, et al. 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotech. 29:644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel CV, et al. 2012. Primitive duplicate Hox clusters in the European eel’s genome. PLoS One 7:e32231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier LW, et al. 2004. Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature 432:695–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegg S, Brinkmann H, Taylor JS, Meyer A. 2004. Phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genome duplication correlates with the diversification of Teleost fish. J Mol Evol 59:190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, et al. 2013. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley I, Hale ME, Prince VE. 2005. Duplication events and the evolution of segmental identity. Evol Dev. 7:556–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue JG, Miya M, Tsukamoto K, Nishida M. 2003. Basal actinopterygian relationships: a mitogenomic perspective on the phylogeny of the “ancient fish”. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 26:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, et al. 2004. Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype. Nature 431:946–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FC, et al. 2012. The genomic basis of adaptive evolution in threespine sticklebacks. Nature 484:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, et al. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30:1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M, et al. 2007. The medaka draft genome and insights into vertebrate genome evolution. Nature 447:714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. 2004. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat M. 2013. Scleropages formosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2014.3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T20034A9137739.en. [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K, et al. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:3100–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R, Calcott B, Kainer D, Mayer C, Stamatakis A. 2014. Selecting optimal partitioning schemes for phylogenomic datasets. BMC Evol Biol. 14:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder GV, Liem KF. 1983. The evolution and interrelationships of the actinopterygian fishes. Bull Mus Comp Zool. 150:95–197. [Google Scholar]

- Laurin-Lemay S, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. 2012. Origin of land plants revisited in the light of sequence contamination and missing data. Curr Biol. 22:R593–R594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GQ, Wilson MVH. 1999. Early divergence of Hiodontiformes sensu stricto in East Asia and phylogeny of some Late Mesozoic teleosts from China. In: Arratia G, Schultze HP, editors. Mesozoic fishes 2: systematics and fossil record. Munich (Germany): Dr F. Pfiel; p. 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. 2010. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 463:311–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marçais G, Kingsford C. 2011. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27:764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Bryant SH. 2004. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W327–W331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2014. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh SE, et al. 2014. The cavefish genome reveals candidate genes for eye loss. Nat Commun. 5:5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Van de Peer Y. 2005. From 2R to 3R: evidence for a fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD). Bioessays 27:937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misof B, et al. 2013. Selecting informative subsets of sparse supermatrices increases the chance to find correct trees. BMC Bioinformatics 14:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Shamsudin MI, et al. 2011. Molecular characterization of relatedness among colour variants of Asian Arowana (Scleropages formosus). Gene 490:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu XD, et al. 2012. Mitochondrial DNA as effective molecular markers for the genetic variation and phylogeny of the family Osteoglossidae. Gene 511:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan N, Pop N. 2013. Sequence assembly demystified. Nat Rev Genet. 14:157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near TJ, et al. 2012. Resolution of ray-finned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109:13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JS. 1994. Fish of the world. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 32:268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo JC, Butts GT, Nery MF, Storz JF, Hoffmann FG. 2013. Whole-genome duplication and the functional diversification of teleost fish hemoglobins. Mol Biol Evol. 30:140–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. 2007. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 23:1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. 2009. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? In: Batzoglou S, editor. Research in computational molecular biology. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; p. 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C. 1998. Comments on basal teleosts and teleostean phylogeny, by Gloria Arratia. Copeia 1107–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C, Rosen DE. 1977. Review of ichthyodectiform and other Mesozoic teleost fishes, and the theory and practice of classifying fossils. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 158:81–172. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, et al. 2013. IDBA-tran: a more robust de novo de Bruijn graph assembler for transcriptomes with uneven expression levels. Bioinformatics 29:i326–i334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2010. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5:e9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Rechavi M, et al. 2001. Euteleost fish genomes are characterized by expansion of gene families. Genome Res. 11:781–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau EB, et al. 2014. The genome and linkage map of the northern pike (Esox lucius): conserved synteny revealed between the salmonid sister group and the Neoteleostei. PLoS One 9:e102089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salichos L, Rokas A. 2013. Inferring ancient divergences requires genes with strong phylogenetic signals. Nature 497:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini F, Harmon L, Carnevale G, Alfaro M. 2009. Did genome duplication drive the origin of teleosts? A comparative study of diversification in ray-finned fishes. BMC Evol Biol. 9:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M, et al. 2013. The genome of the platyfish, Xiphophorus maculatus, provides insights into evolutionary adaptation and several complex traits. Nat Genet. 45:567–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber F, Patricio M, Muffato M, Pignatelli M, Bateman A. 2014. TreeFam v9: a new website, more species and orthology-on-the-fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D922–D925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y, Gras R. 2011. 43 genes support the lungfish-coelacanth grouping related to the closest living relative of tetrapods with the Bayesian method under the coalescence model. BMC Res Notes. 4:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen XY, et al. 2014. The first transcriptome and genetic linkage map for Asian arowana. Mol Ecol Resour. 14:622–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha R, et al. 2014. QTrim: a novel tool for the quality trimming of sequence reads generated using the Roche/454 sequencing platform. BMC Bioinformatics 15:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Star B, et al. 2011. The genome sequence of Atlantic cod reveals a unique immune system. Nature 477:207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. 1993. Simple methods for testing the molecular evolutionary clock hypothesis. Genetics 135:599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki N, et al. 2004. The phylogenetic relationship of tetrapod, coelacanth, and lungfish revealed by the sequences of forty-four nuclear genes. Mol Biol Evol. 21:1512–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 30:2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Braasch I, Meyer A. 2001. Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 356:1661–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, et al. 2014. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505:174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, et al. 2001. The sequence of the human genome. Science 291:1304–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, et al. 2012. Community annotation and bioinformatics workforce development in concert—Little Skate Genome Annotation Workshops and Jamborees. Database (Oxford) 2012:bar064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TD, Watanabe CK. 2005. GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics 21:1859–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyffels J, et al. 2014. SkateBase, an elasmobranch genome project and collection of molecular resources for chondrichthyan fishes. F1000Res. 3:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, et al. 2014. Genome sequence and genetic diversity of the common carp, Cyprinus carpio. Nat Genet. 46:1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Smith SA. 2014. Orthology inference in nonmodel organisms using transcriptomes and low-coverage genomes: improving accuracy and matrix occupancy for phylogenomics. Mol Biol Evol. 31:3081–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue G, Liew W, Orban L. 2006. The complete mitochondrial genome of a basal teleost, the Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus, Osteoglossidae). BMC Genomics 7:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimin AV, et al. 2013. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics 29:2669–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M, Guo B, Tao W, Arratia G, He S. 2012. Integrating multi-origin expression data improves the resolution of deep phylogeny of ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii). Sci Rep. 2:665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.