Abstract

Vibrio metoecus is the closest relative of Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the potent diarrheal disease cholera. Although the pathogenic potential of this new species is yet to be studied in depth, it has been co-isolated with V. cholerae in coastal waters and found in clinical specimens in the United States. We used these two organisms to investigate the genetic interaction between closely related species in their natural environment. The genomes of 20 V. cholerae and 4 V. metoecus strains isolated from a brackish coastal pond on the US east coast, as well as 4 clinical V. metoecus strains were sequenced and compared with reference strains. Whole genome comparison shows 86–87% average nucleotide identity (ANI) in their core genes between the two species. On the other hand, the chromosomal integron, which occupies approximately 3% of their genomes, shows higher conservation in ANI between species than any other region of their genomes. The ANI of 93–94% observed in this region is not significantly greater within than between species, meaning that it does not follow species boundaries. Vibrio metoecus does not encode toxigenic V. cholerae major virulence factors, the cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus. However, some of the pathogenicity islands found in pandemic V. cholerae were either present in the common ancestor it shares with V. metoecus, or acquired by clinical and environmental V. metoecus in partial fragments. The virulence factors of V. cholerae are therefore both more ancient and more widespread than previously believed. There is high interspecies recombination in the core genome, which has been detected in 24% of the single-copy core genes, including genes involved in pathogenicity. Vibrio metoecus was six times more often the recipient of DNA from V. cholerae as it was the donor, indicating a strong bias in the direction of gene transfer in the environment.

Keywords: Vibrio metoecus, Vibrio cholerae, horizontal gene transfer, genomic islands, integron, comparative genomics

Introduction

The genus Vibrio constitutes a diverse group of gammaproteobacteria ubiquitous in marine, brackish, and fresh waters. There are currently over 100 species of vibrios that have been described (Gomez-Gil et al. 2014). This includes clinically significant pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus among many others. Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the potent diarrheal disease cholera, is the most notorious of these human pathogens. Cholera remains a major public health concern, with an estimated 1.2–4.3 million cases and 28,000–142,000 deaths every year worldwide (Ali et al. 2012).

A novel Vibrio isolate, initially identified as a nonpathogenic environmental variant of V. cholerae (Choopun 2004), was recently revealed to be a distinct species based on comparative genomic analysis (Haley et al. 2010). Additional environmental strains of this species have been isolated since then (Boucher et al. 2011). Also, since 2006, several clinical strains have been recovered from a range of specimen types (blood, stool, ear, and leg wound) and characterized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA). This recently described species, now officially called V. metoecus (Kirchberger et al. 2014), is even more closely related to V. cholerae than any other known Vibrio species based on biochemical and genotypic tests (Boucher et al. 2011; Kirchberger et al. 2014). Previously, the closest known relative of V. cholerae was Vibrio mimicus, which was first described as a biochemically atypical strain of V. cholerae and named after the fact that it “mimicked V. cholerae” phenotypically (Davis et al. 1981).

The discovery of a closely related but distinct species which co-occurs with V. cholerae in the environment (Boucher et al. 2011) presents a unique opportunity to investigate the dynamics of interspecies interactions at the genetic level. In their environmental reservoir, bacteria can acquire genetic material from other organisms as a result of horizontal gene transfer (HGT; De la Cruz and Davies 2000). HGT plays an important role in the evolution, adaptation, maintenance, and transmission of virulence in bacteria. It can launch nonpathogenic environmental strains into new pathogenic lifestyles if they obtain the right virulence factors. The two major virulence factors that have led to the evolution from nonpathogenic to toxigenic V. cholerae are the cholera toxin (CTX), which is responsible for the cholera symptoms (Waldor and Mekalanos 1996), and the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP), which is necessary for the colonization of the small intestine in the human host (Taylor et al. 1987). These elements are encoded in genomic islands, specifically called pathogenicity islands, and have been acquired horizontally by phage infections (Waldor and Mekalanos 1996; Karaolis et al. 1999). Another genomic island, the integron, is used to capture and disseminate gene cassettes, such as antibiotic resistance genes (Stokes and Hall 1989). Integrons have been identified in a diverse range of bacterial taxa, and are known to play a major role in genome evolution (Mazel 2006; Boucher et al. 2007). As evidenced by multiple HGT events across a wide range of phylogenetic distances, integrons themselves, not only the cassettes they carry, may have been mobilized within and between species throughout their evolutionary history (Boucher et al. 2007). Integrons are ubiquitous among vibrios, but in some species, such as V. cholerae, it can occupy up to 3% of the genome and can contain over a hundred gene cassettes with a wide range of biochemical functions (Mazel et al. 1998; Heidelberg et al. 2000).

Here, we investigate the extent of genetic interaction between V. metoecus and V. cholerae through comparative genomic analysis, with the focus on the genomic islands, known hotspots for HGT (Dobrindt et al. 2004). The co-isolation of both species in the same environment (Boucher et al. 2011) indicates that V. metoecus is likely in constant interaction with V. cholerae. Our results show that there is a high rate of gene exchange between species, so rapid in the chromosomal integron that this region is indistinguishable between species. Multiple HGT events were also inferred in the core genome, including genes implicated in pathogenicity, with the majority with V. metoecus as a recipient of V. cholerae genes, suggesting a directional bias in interspecies gene transfer.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains Used

The V. metoecus and V. cholerae isolates sequenced in this study as well as genome sequences of additional isolates for comparison are listed in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online. Environmental strains of V. metoecus and V. cholerae were isolated from Oyster Pond (Falmouth, MA) on August and September 2009 using previously described methods (Boucher et al. 2011). Isolates were grown overnight at 37 °C in tryptic soy broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) with 1% NaCl (BDH, Toronto, ON, Canada). The sequences of the clinical V. metoecus strains were determined by the CDC. Additional sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD) GenBank database.

Genomic DNA Extraction and Quantitation

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight bacterial cultures with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The concentration for each extract was determined using the Quant-iT PicoGreen double-stranded DNA Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and the Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

The genomic DNA extracts were sent to the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre (Montréal, QC, Canada) for sequencing, which was performed using the TrueSeq library preparation kit and the HiSeq PE100 sequencing technology (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The contiguous sequences were assembled de novo with the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Functional annotations of the draft genomes were done in RAST v2.0 (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology; Aziz et al. 2008).

Whole Genome Alignment

A circular BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) atlas was constructed to visually compare whole genomes. The annotated genome sequences of V. metoecus and V. cholerae were aligned by BLASTN (Altschul et al. 1990) against a reference, V. cholerae N16961 (Heidelberg et al. 2000), using the CGView Comparison Tool (Grant et al. 2012).

Determination of Orthologous Gene Families and Pan-Genome Analysis

Orthologous groups of open-reading frames (ORFs) from all strains of V. metoecus and V. cholerae were determined by pairwise bidirectional BLASTP using the OrthoMCL pipeline v2.0 (Li et al. 2003) with 30% match cutoff, as proteins sharing at least 30% identity are predicted to fold similarly (Rost 1999). The gene families were assigned into functional categories based on the Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG) database (Tatusov et al. 2000). The pan- and core genome profiles for each species were determined with PanGP v1.0.1 (Zhao et al. 2014) using the distance guide algorithm, repeated 100 times. Sample size and amplification coefficient were set to 1,000 and 100, respectively.

Determination of Genomic Islands

The major genomic islands of V. cholerae N16961 were identified using IslandViewer (Langille and Brinkman 2009) and confirmed with previously published data (Heidelberg et al. 2000; Chun et al. 2009). To determine whether a putative homolog is present, ORFs in these genomic islands were compared against the ORFs of V. metoecus and V. cholerae by calculating the BLAST score ratio (BSR) between reference and query ORF (Rasko et al. 2005) using a custom-developed Perl script (National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg, MB, Canada). Only BSR values of at least 0.3 (for 30% amino acid identity) were considered (Rost 1999).

Determination of the Integron Regions

The chromosomal integron regions of V. metoecus and V. cholerae were recovered by finding the locations of the integron integrase gene intI4 and the attI and attC recombination sites, identified with the ISAAC software (Improved Structural Annotation of attC; Szamosi 2012). The intI4 and gene cassette sequences were used to calculate the ANI (Konstantinidis and Tiedje 2005; Goris et al. 2007) between strains (intra- and interspecies) in JSpecies v1.2.1 (Richter and Rosselló-Móra 2009), using the bidirectional best BLAST hits between nucleotides. The ANI of the integron region was compared with the ANI of 1,560 single-copy core ORFs (≈1.42 Mb).

Phylogenetic Analyses

Using the PhyloPhlAn pipeline v0.99 (Segata et al. 2013), 3,978 amino acid positions based on 400 universally conserved bacterial and archaeal proteins were determined. The concatenated alignment was used to construct a core genome maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree, with a BLOSUM45 similarity matrix using the Jones-Taylor-Thorton (JTT) + category (CAT) amino acid evolution model optimized for topology/length/rate using the nearest neighbor interchange (NNI) topology search. Robustness of branching was estimated with Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like (SH-like) support values from 1,000 replicates.

Nucleotide sequences within a gene family were aligned with ClustalW v2.1 (Larkin et al. 2007), and an ML tree was constructed using RAxML v8.1.17 (Stamatakis 2014) using the general time reversible (GTR) nucleotide substitution model and gamma distribution pattern. Robustness of branching was estimated with 100 bootstrap replicates. Interspecies gene transfer events were determined and quantified by comparison of tree topologies using the Phangorn package v1.99-11 (Schliep 2011) in R v3.1.2 (R Development Core Team 2014). A tree was partitioned into clades and determined whether the clades were perfect or not. Following the definition by Schliep et al. (2011), we defined a perfect clade as a partition that is both complete and homogeneous for a given taxonomic category (e.g., a clade with all V. metoecus, and only V. metoecus). At least one gene transfer event was hypothesized if a tree did not show perfect clades for neither V. metoecus nor V. cholerae (i.e., in a rooted tree, V. metoecus and V. cholerae are both polyphyletics).

Resulting alignments of the 1,184 single-copy core gene families not exhibiting HGT were concatenated, and alignment columns with at least one gap were removed using Geneious (Kearse et al. 2012). A final alignment with a total length of 771,455 bp was obtained and used to construct a core genome ML phylogenetic tree with RAxML v8.1.17 (Stamatakis 2014), as described above.

Results and Discussion

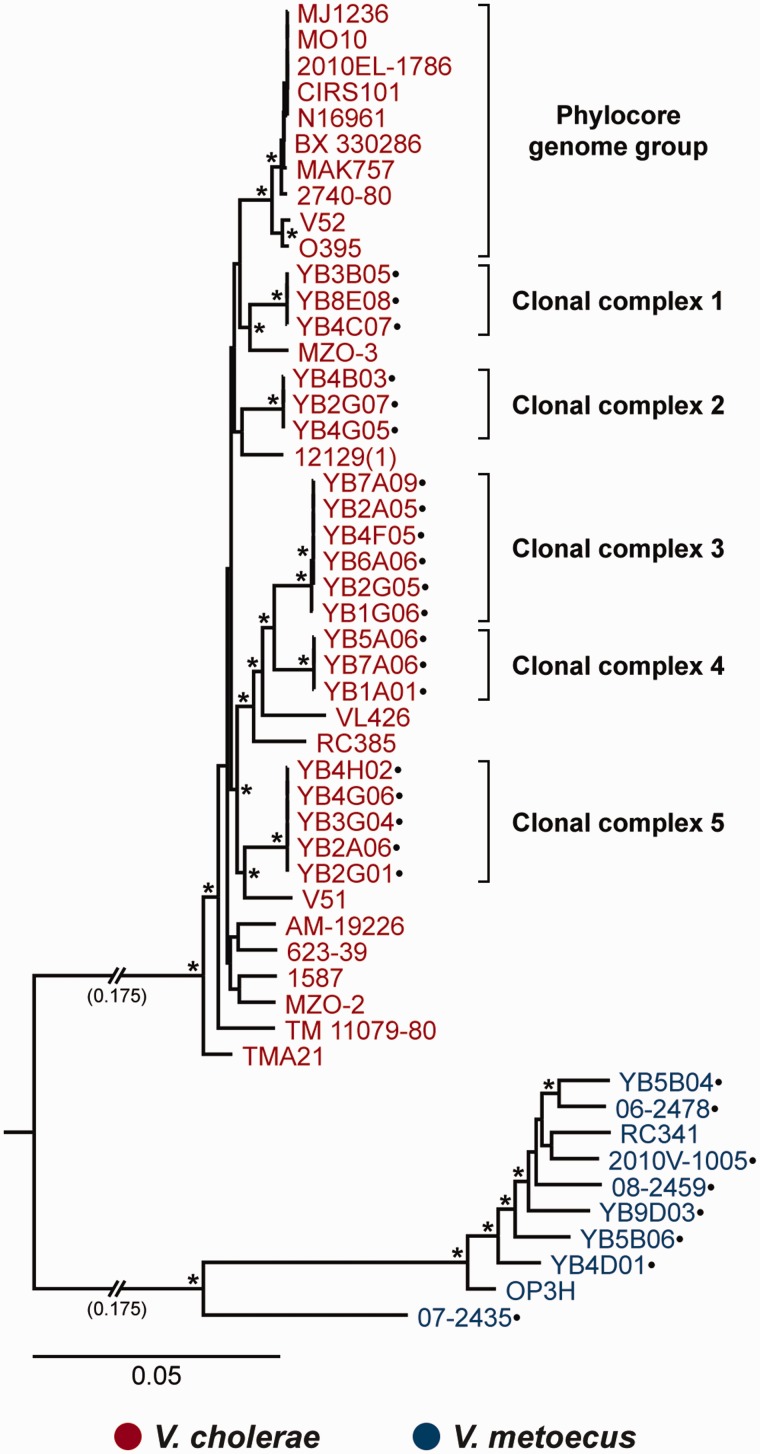

Vibrio cholerae is widely studied, and the genomes of globally diverse clinical and environmental isolates are available (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). On the other hand, there are currently only two V. metoecus genomes available. Strain RC341 was isolated from Chesapeake Bay (MD) in 1998. It was presumptively identified as a variant V. cholerae based on 16 S ribosomal RNA gene similarity to V. cholerae (Choopun 2004), but was later reclassified into its current species (Haley et al. 2010; Kirchberger et al. 2014). Strain OP3H was isolated in 2006 from Oyster Pond, a brackish pond in Cape Cod, MA. OP3H is considered the type strain of V. metoecus, which was recently officially described as a species (Kirchberger et al. 2014). A screen was performed for atypical V. cholerae isolates from a historical collection of clinical isolates at the CDC and identified that several of them were, in fact, V. metoecus (Boucher et al. 2011). Additional environmental V. metoecus strains were isolated in 2009 from Oyster Pond. While examining the population structure and surveying the mobile gene pool of environmental V. cholerae in Oyster Pond, Boucher et al. (2011) discovered that both V. metoecus and V. cholerae co-occur in this location. To gain a better understanding of the V. metoecus species, we sequenced the genomes of four clinical V. metoecus strains originating from patients in the United States and an additional four from Oyster Pond. To be able to evaluate genetic interactions between strains of two different species from the same environment, we sequenced an additional 20 genomes of V. cholerae isolates from the same Oyster Pond samples (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.—

The phylogenetic relationship of the V. metoecus and V. cholerae strains. The ML phylogenetic tree was constructed from the concatenated sequence alignment of single-copy core gene families (771,455 bp). All reliable bootstrap support values are indicated with * and are at least 97% for this tree. The scale bar represents nucleotide substitutions per site. Shortened branch lengths, approximately 3.5× the scale bar (0.175), are indicated. Strains with their genomes sequenced in this study are indicated by dots. Multiple V. cholerae strains from Oyster Pond (MA) belong to the same clonal complex.

Vibrio metoecus: The Closest Relative of V. cholerae

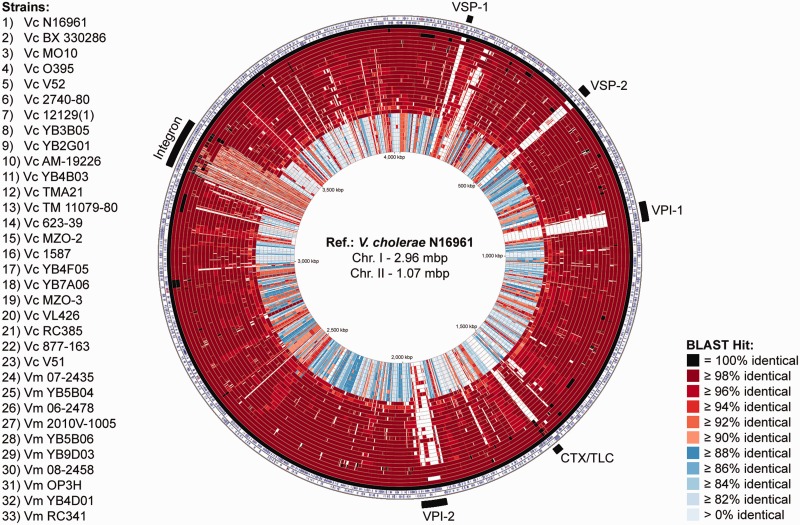

To obtain a visual comparison of the genomes, provide an overall impression of genome architecture and identify highly conserved and divergent regions, a circular BLAST atlas was constructed (Grant et al. 2012). Vibrio metoecus and representative V. cholerae genomes were compared by BLASTN alignment of coding sequences (Altschul et al. 1990) against the reference V. cholerae N16961, a pandemic strain from Bangladesh isolated in 1971 whose entire genome was sequenced to completion and carefully annotated (Heidelberg et al. 2000). The BLAST atlas shows a clear distinction between species, as sequence identity is higher within a species than between different species for most genes (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.—

The V. metoecus (Vm) and V. cholerae (Vc) BLAST atlas. The map compares sequenced genomes against the reference (ref.), V. cholerae N16961. The two outermost rings show the forward and reverse strand sequence features of the reference. The next 33 rings show regions of sequence similarity detected by BLASTN comparisons between genes of the reference and query genomes. White regions indicate the absence of genes. Outermost black bars indicate the location of the major genomic islands. VSP, Vibrio seventh pandemic island; VPI, Vibrio pathogenicity island; CTX/TLC, cholera toxin/toxin-linked cryptic; chr., chromosome.

On average, V. metoecus shares 84% of its ORFs with V. cholerae, whereas 89–91% ORFs are shared between strains of the same species (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). In contrast, V. mimicus, previously the closest known relative of V. cholerae, shares only 64–69% of ORFs with V. cholerae (Hasan et al. 2010). It was determined previously that the recommended cutoff point for prokaryotic species delineation by DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) is 70%, which corresponds to 85% of conserved protein-coding genes for a pair of strains (Goris et al. 2007). These results show clear distinction between the three closely related species based on conserved genes, and V. metoecus is a much closer relative to V. cholerae than V. mimicus.

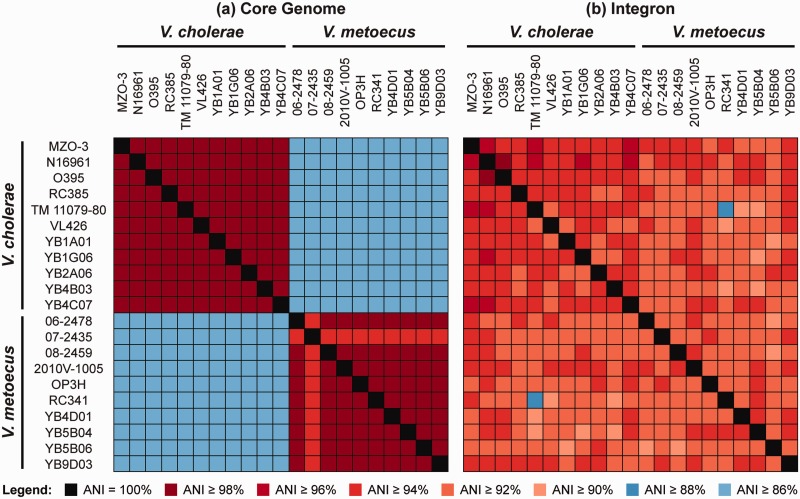

Another fundamental measure of relatedness between bacterial strains is ANI. This measure was proposed as a modern replacement to the traditional DDH method to determine relatedness of organisms, but still provide equivalent information (i.e., DNA–DNA similarity; Konstantinidis and Tiedje 2005; Goris et al. 2007). The ANI of the core genome is 86–87% between species and 98–100% within species (fig. 3a), showing a clear distinction between V. metoecus and V. cholerae. Two organisms belonging to the same species will have an ANI of at least 95%, corresponding to 70% DDH (Goris et al. 2007), although earlier studies have proposed a 94% cutoff (Konstantinidis and Tiedje 2005). For this reason, we have currently classified the clinical strain 07-2435 as V. metoecus as it shows 94% ANI with other V. metoecus strains but only 87% ANI with V. cholerae (fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.—

ANI of the core genome versus chromosomal integron region of V. metoecus and V. cholerae. (a) Intra- and interspecies pairwise comparison of the 1,560 single-copy core genes (≈1.42 Mb). (b) Intra- and interspecies pairwise comparison of the integron gene cassettes.

A Portion of the Genome Escapes the Species Boundary between V. metoecus and V. cholerae

The BLAST atlas allows for the clear distinction between strains belonging to the V. cholerae species and those belonging to the V. metoecus species. However, there is a clear and visible exception in one genomic region: The integron. Sequence identity of genes found in the integron region does not seem to differ within and between species (fig. 2).

The integron is a region of the genome capable of gene capture and excision (Stokes and Hall 1989) and can occupy up to 3% of the genome in V. cholerae (Heidelberg et al. 2000). Although the size of the chromosomal integron region varies between isolates, there is no significant difference in length and number of ORFs between species and between clinical and environmental isolates (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). The ANI of the integron region was determined between pairs of strains and compared with the ANI of the core genome (fig. 3). Although ANI is 86–87% between species and 98–100% within species for the core genome (fig. 3a), the integron region displays an average pairwise ANI of 93–94%, both within and between species (fig. 3b). Gene cassettes from the 10 V. metoecus and 11 V. cholerae integron regions were grouped into orthologous gene families, and the occurrence of HGT was quantified for gene families with at least two V. metoecus and V. cholerae members by the construction of phylogenetic trees. Of the 116 gene families considered, 109 or 94% do not show distinct separation between the two species in a phylogenetic tree. The high number of genes shared between species and their high nucleotide identity are likely the result of frequent interspecies HGT (figs. 2 and 3b). A previous study by Boucher et al. (2011) showed that there is indeed a high frequency of gene exchange in the integron region between V. cholerae and V. metoecus, specifically from the same geographic location (i.e., V. cholerae and V. metoecus in Oyster Pond) as compared with the same species in different locations (i.e., V. cholerae from Bangladesh and the United States). Here, we show that not only is the frequency of interspecies HGT high in the integron, but that its level is such that this region becomes indistinguishable between species.

Although the functions of the majority of integron gene cassettes are unknown (Boucher et al. 2007), many of the known genes are antibiotic resistance genes and are implicated in the evolution of bacteria highly resistant to antibiotics (Collis and Hall 1995; Rowe-Magnus and Mazel 2002). Looking into the predicted functions of the 116 gene families comprising 1,452 gene cassettes, the majority of which are shared between V. metoecus and V. cholerae, reveals genes that encode proteins involved in transport and metabolism of various molecules (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online), suggesting a major contributing function of the integron for host acquisition and distribution of important resources in the environment by bacteria (Koenig et al. 2008). Gene cassettes encoding nicotinamidase-related amidases are present in multiple copies. Nicotinamidase catalyzes the deamination of nicotinamide to produce ammonia and nicotinic acid (Petrack et al. 1965). A key enzyme in many organisms, nicotinamidase has been shown to be important in the proliferation of bacteria pathogenic to mammalian hosts including humans (Purser et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2004). Other genes present are involved in basic cellular functions such as acetyltransferases, involved in posttranslational modifications of ribosomal proteins, the functional significance of which remains unclear but may have regulatory roles (Nesterchuk et al. 2011). Some genes are part of the plasmid stabilization systems, which include the toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems. TA systems are frequently found in gene cassette arrays for the stabilization and prevention of loss of gene cassettes. They also play additional roles in stress response, bacterial persistence, and phage defense (Iqbal et al. 2015).

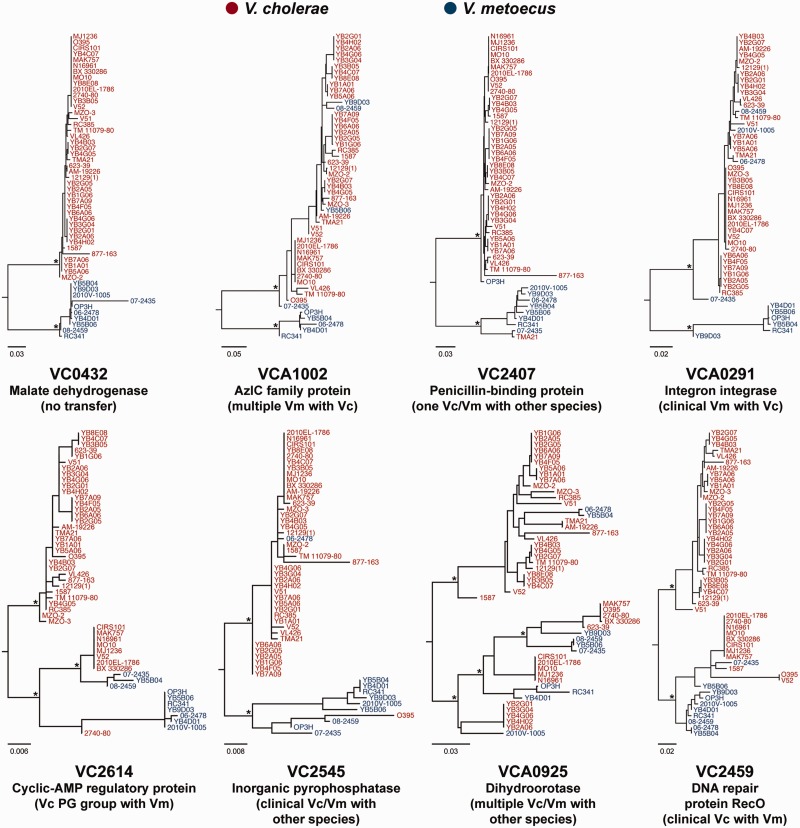

A Lack of Reciprocity: Directional Gene Flow from V. cholerae to V. metoecus

To get a quantitative estimate of the amount of HGT between V. cholerae and V. metoecus, we investigated the amount of interspecies recombination taking place in their core genomes. An ML tree was constructed for each of the 1,947 gene families comprising the V. metoecus–V. cholerae core genome (fig. 4). The trees were then analyzed for gene transfer events by partitioning them into clades (Schliep 2011). In our analysis, following the definition by Schliep et al. (2011), a gene transfer is hypothesized if a member of one species clusters with members of the other species in a clade, and the tree cannot be partitioned into perfect clades, which must consist of all members from the same species and only of that species. Considering only the single-copy core genes, we have inferred interspecies HGT in 376 of 1,560 genes (24%; supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online). Our analysis excluded 387 core genes that have duplicates in at least one of the genomes, as it is difficult to reliably assess HGT in genes from large paralogous families (Ge et al. 2005). Using this method, it was possible to determine directionality of HGT, whether from V. cholerae to V. metoecus or vice versa. HGT was qualified by examining the individual gene trees, and only reliable clustering with at least 70% bootstrap support was considered (Hillis and Bull 1993). A total of 655 interspecies gene transfer events were detected, with the majority (489 or 75%; P = 0.0053) with V. metoecus as the recipient (i.e., V. metoecus members clustering within the V. cholerae clade). On the other hand, we detected 166 (25%) of gene transfer events with V. cholerae as the recipient (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 4.—

Representative HGT between V. metoecus (Vm) and V. cholerae (Vc). The trees are representative ML phylogenetic trees from 1,560 orthologous families of single-copy core genes showing various examples of transfer events. Bottom trees: Transfers involving at least one clinical V. cholerae clustering with V. metoecus. Relevant bootstrap support (>70%) is indicated with *. The scale bars represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

To investigate whether this bias in directionality of HGT was due to differences in the origin or ecology of strains from one species or the other, we performed the analysis using only environmental strains from Oyster Pond. To ensure equal genetic diversity for both species, we compared the same number of isolates from each species. The 20 V. cholerae isolates we sequenced for this study can be grouped into five clonal complexes as determined by multilocus sequence typing of seven housekeeping genes. All the isolates from the same clonal complex cluster together in a core genome phylogenetic tree (fig. 1). They also exhibit 100% ANI only with each other but not with isolates from other clonal complexes (supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online). Indeed, members of the same clonal complex always cluster together in all the individual gene trees examined (fig. 4). We therefore randomly chose one isolate from each V. cholerae clonal complex from Oyster Pond, yielding a final data set of five genomes from each species. A total of 224 interspecies gene transfer events were detected in this environment-specific data set, where 192 (86%; P = 0.0012) involved V. metoecus as the recipient and only 32 (14%) with V. cholerae as the recipient (table 1). One possibility to explain this bias could be that V. cholerae genes are more abundant in the environment and therefore more accessible to V. metoecus. Indeed, using culture-based methods, V. cholerae was ten times more abundant than V. metoecus in Oyster Pond. Another possibility is that V. cholerae is more refractory to HGT as they contain more barriers to gene uptake, such as restriction-modification systems, or that V. metoecus is more permissive, containing more DNA uptake systems (conjugative plasmids, natural competence machinery or phages). However, no significant difference could be found in the number or nature of proteins involved in restriction-modification or DNA uptake systems between V. metoecus and V. cholerae in our study, although poorly transformable V. cholerae, despite having an intact and perfectly functioning DNA uptake system, have been reported (Katz et al. 2013). Additionally, nuclease activity by Dns, Xds, and other DNases can inhibit natural transformation (Blokesch and Schoolnik 2008; Gaasbeek et al. 2009). We also surveyed our V. metoecus and V. cholerae genomes for predicted DNases and found no significant difference between species.

Table 1.

HGT Count for Vibrio metoecus and Representative Vibrio cholerae Strains from Oyster Pond (MA) Based on 376 Single-Copy Core Genes with Inferred HGT

| Species and Strain | HGT Count | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Vibrio metoecus OP3H | 55 | 25 |

| Vibrio metoecus YB4D01 | 43 | 19 |

| Vibrio metoecus YB5B06 | 37 | 17 |

| Vibrio metoecus YB5B04 | 30 | 13 |

| Vibrio metoecus YB9D03 | 27 | 12 |

| 192 | 86 | |

| Vibrio cholerae YB2G01 (CC 5) | 16 | 7 |

| Vibrio cholerae YB4F05 (CC 3) | 9 | 4 |

| Vibrio cholerae YB4B03 (CC 2) | 4 | 2 |

| Vibrio cholerae YB7A06 (CC 4) | 2 | 1 |

| Vibrio cholerae YB3B05 (CC 1) | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 32 | 14 |

Note.—Only one strain from each clonal complex (CC) was included. An HGT event was hypothesized when a strain clustered with members of the other species in a phylogenetic tree, with reliable bootstrap support (>70%). Unequal variance t-test, P = 0.0012.

Despite the directional gene transfer from V. cholerae to V. metoecus, it seems that the latter might have contributed to the virulence of its more famous relative by HGT. Interspecies recombination was detected in four core genes where at least one clinical V. cholerae grouped in the same clade with V. metoecus (fig. 4). Interestingly, three of these genes are implicated, whether directly or indirectly, in V. cholerae pathogenesis. VC2614 encodes a cyclic adenosine monophosphate regulatory protein, a global regulator of gene expression in V. cholerae including CTX and TCP (Skorupski and Taylor 1997). It appears that HGT in this case occurred in the ancestor of the phylocore genome (PG) group, which contains all pandemic strains (fig. 1; Chun et al. 2009), with a clinical V. metoecus strain as the possible donor. The new version of this cyclic-AMP regulatory protein was eventually lost in the classical O1 strain (O395). VC2545 encodes an inorganic pyrophosphatase, and its expression in V. cholerae may play an important role during human and mouse infection (Lombardo et al. 2007). This transfer was only between clinical V. metoecus and classical O1. VCA0925 encodes a dihydroorotase essential for pyrimidine biosynthesis. Biosynthesis of nucleotides is the single most critical metabolic function for growth of pathogenic bacteria in the bloodstream because of scarcity of nucleotide precursors but not other nutrients, and the genes involved serve as potential antibiotic targets for treatments of blood infection (Samant et al. 2008). Here, gene transfer involved not just the PG group of V. cholerae but also the environmental strains of clonal complex 5 and 623-39.

Although these interspecies recombination events do not represent novel gene acquisitions, gaining a new allele of a gene can often have important consequences in a pathogen, changing its fitness in the host. This has been demonstrated for single-point mutations in ompU, vpvC, and ctxB. The ompU gene encodes for the major outer membrane porin OmpU, generally for the transport of hydrophilic solutes, but has been shown to provide V. cholerae resistance to bile acids and antimicrobial peptides in the host (Provenzano et al. 2000; Mathur and Waldor 2004). It is suggested that it can also act as a receptor for phage to infect V. cholerae (Seed et al. 2014). The vpvC gene encodes for diguanylate cyclase, and the mutation results in a switch from the smooth to rugose phenotype in V. cholerae (Beyhan and Yildiz 2007). The single-point mutations in these genes result in a V. cholerae that is less susceptible to phage infection, contributing to the evolutionary success of the pathogen (Beyhan and Yildiz 2007; Seed et al. 2014). Vibrio cholerae responsible for cholera outbreaks in Bangladesh have changing genotypes of ctxB, a subunit of CTX (Waldor and Mekalanos 1996), also caused by a single-point mutation (Rashed et al. 2012). The years 2006 and 2007 saw a dominance of V. cholerae with the ctxB genotype 1 (ctxB1). Vibrio cholerae with the ctxB genotype 7 (ctxB7) outcompeted ctxB1 from 2008 to 2012. However, there appears to be a shift back to ctxB1 since 2013. The changing ctxB genotypes were associated with differing levels of severity of cholera. This also suggests CTX phage-mediated evolution, survival, and dominance of V. cholerae (Rashed et al. 2012; Rashid et al. 2015).

Components of Major Pathogenicity Islands Are More Ancient than the V. cholerae Species

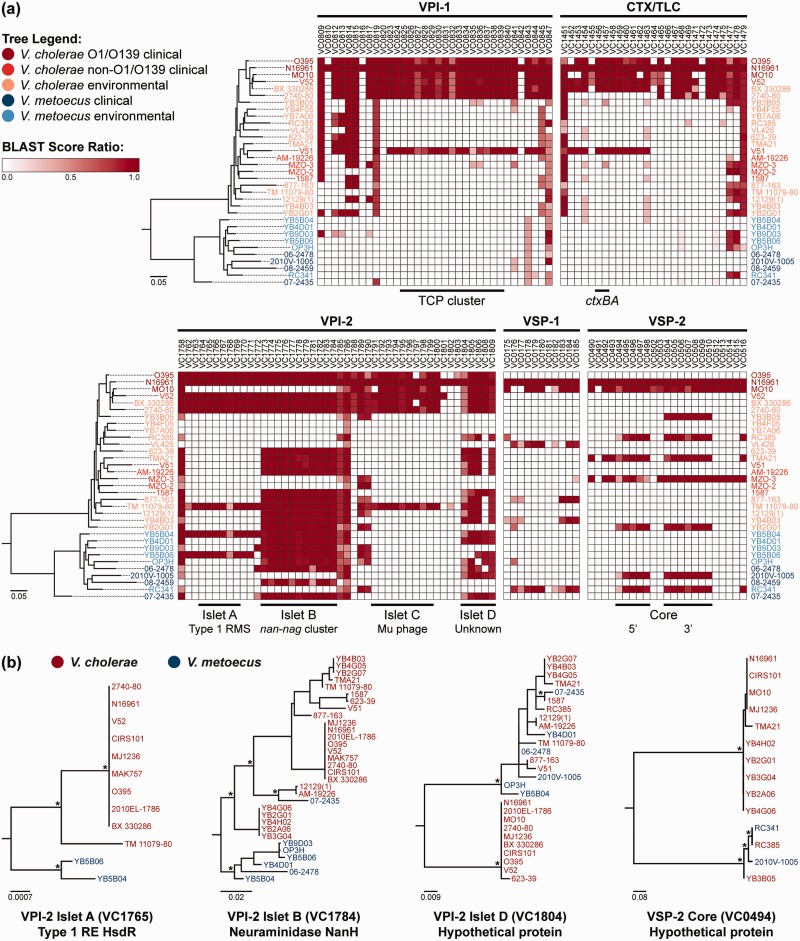

A BSR map (Rasko et al. 2005) was constructed to show the presence or absence of the genes comprising the major pathogenicity islands in various V. metoecus and V. cholerae isolates (fig. 5). Using the genes from V. cholerae N16961 as reference, BLASTP was used to determine the presence of homologous genes in the other strains (Altschul et al. 1990). The major V. cholerae virulence factors, CTX and TCP, which are encoded by pathogenicity islands that have been acquired horizontally by phage infections of the CTXΦ and VPIΦ, respectively (Waldor and Mekalanos 1996; Karaolis et al. 1999), are absent from all clinical and environmental V. metoecus (fig. 5a). The absence of CTX and TCP in V. metoecus is consistent with the absence of reports on a toxigenic V. metoecus.

Fig. 5.—

Virulence factors present in V. metoecus and V. cholerae. (a) The phylogenetic relationship of the V. metoecus and V. cholerae strains is shown on the left of each BSR map. The ML phylogenetic tree was constructed using 3,978 amino acid positions based on 400 universally conserved bacterial and archaeal proteins. The scale bars represent amino acid substitutions per site. The columns on the BSR maps show genes (locus tags) from genomic islands VPI-1, CTX/TLC, VPI-2, VSP-1, and VSP-2 of the reference, V. cholerae N16961. The black bars at the bottom of the BSR maps indicate the TCP cluster of VPI-1, ctxAB of CTX/TLC, islets of VPI-2, and core regions of VSP-2. The gradient bar shows the BSRs and their corresponding colors, with white regions indicating the absence of genes. Only BSR values of at least 0.3 were included. VPI, Vibrio pathogenicity island; CTX/TLC, cholera toxin/toxin-linked cryptic; VSP, Vibrio seventh pandemic island; RMS, restriction-modification system. (b) Representative ML phylogenetic trees of orthologous gene families of the VPI-2 islets and the VSP-2 core. Relevant bootstrap support (>70%) is indicated with *. The scale bars represent nucleotide substitutions per site. RE, restriction endonuclease.

Interestingly, our results show some of the other major pathogenicity islands to be present in some V. metoecus and nonpandemic V. cholerae strains in fragments and not as a complete presence or absence. This is evident in the Vibrio pathogenicity island 2 (VPI-2), which can be divided into four subclusters we call “islets,” as indicated in figure 5a. These four islets match the previous description of Jermyn and Boyd (2002) for VPI-2: 1) A type-1 restriction-modification system for protection against viral infection, 2) a nan-nag cluster for sialic acid metabolism, 3) a Mu phage-like region, and 4) a number of ORFs of unknown function. We hypothesize two scenarios as to the fragmentation of these genomic islands 1) that the islands were obtained as a whole and sections were eventually lost, or 2) that the islands were acquired independently in islets and were accreted into the same region in the genome. Evolution would favor the latter hypothesis, as it is more parsimonious for fewer environmental strains to independently acquire certain islets of the islands rather than a majority of the strains acquiring whole islands and losing most regions eventually (Freeman and Herron 2007). Phylogenetic trees were constructed for the gene families that constitute the four putative islets of VPI-2. Gene trees for islet B, the nan-nag cluster, show distinct clustering of V. metoecus and V. cholerae, suggesting the acquisition of this region by a common ancestor, which diverged and evolved independently after speciation, with more recent isolated HGT events between V. metoecus and V. cholerae (fig. 5b and supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). A similar pattern of distinct clustering of V. metoecus and V. cholerae is also observed in islet A, but the latter is only present in O1 El Tor V. cholerae and two V. metoecus strains (fig. 5a), suggesting that it was horizontally transferred between the two species and likely absent from their common ancestor. Furthermore, islet C, the putative Mu phage-like region, is only detected in V. cholerae of the PG group and TM 11079-80, an O1 El Tor environmental isolate. This islet is absent in V. metoecus, which suggests a more recent acquisition of this region only by certain V. cholerae. Finally, islet D is prevalent in the majority of the isolates, whether V. metoecus or V. cholerae, which do not cluster by species in the phylogeny (fig. 5b). This suggests frequent interspecies HGT of its component genes. Taken together, these results support that the VPI-2 island emerged by accretion of smaller islets with different evolutionary histories before reaching the form currently found in V. cholerae O1 El Tor or classical pandemic strains. The nan-nag cluster (islet B) is likely ancestral, being present before speciation of V. cholerae and V. metoecus, with islets A and D acquired later by the ancestor of pandemic V. cholerae through HGT within or between species and islet C added most recently through HGT from an unknown source.

The Vibrio seventh pandemic islands 1 and 2 (VSP-1 and VSP-2, respectively) are genomic islands believed to be present and unique only among the seventh pandemic isolates of V. cholerae (Dziejman et al. 2002; O’Shea et al. 2004). These VSPs are hypothesized to provide a fitness advantage to these isolates. However, multiple variants of VSP-2 have been detected in V. cholerae, including non-O1/O139 strains, by acquisition and loss of genes at specific loci within a conserved core genomic backbone (Taviani et al. 2010). This core VSP-2 is also present in two V. metoecus isolates, the clinical 2010 V-1005 and environmental RC341 (fig. 5a), and may have been acquired from V. cholerae, as indicated by the great similarity of genes in this region to V. cholerae and phylogenetic analysis (fig. 5b and supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). This variant of VSP-2 is stable and present in diverse strains isolated from different times and geographic locations and may be the one circulating among non-O1/O139 isolates (Taviani et al. 2010). VSP-1 is present almost in its entirety in environmental V. cholerae VL426 and V. metoecus RC341 (fig. 5a); similar strains in the environment may serve as reservoirs of VSP-1. There is no correlation between the presence of VSP-1 and VSP-2 in non-O1/O139 V. cholerae, indicating that both islands were acquired independently in different HGT events by seventh pandemic V. cholerae (Taviani et al. 2010). The presence of both of the entire VSP-1 and the core of VSP-2 in V. metoecus strains indicate interspecies movement of pathogenicity islands, suggesting that interspecies transfer can contribute to the evolution of pathogenic variants.

Fundamental Genetic Differences between V. metoecus and V. cholerae

To determine genetic differences between V. cholerae and V. metoecus and the unique gene content of each species, we first compiled their pan- and core genomes (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online). The pan-genome is the entire gene repertoire of a bacterial species, whereas the core genome comprises genes shared by all the strains (Tettelin et al. 2005, Vernikos et al. 2015). ORFs from both species were assigned to orthologous groups based on sequence similarity, yielding pan- and core genomes containing 5,613 and 2,089 gene families, respectively, based on the 42 V. cholerae genomes used in this study (supplementary fig. S4a, Supplementary Material online). This differs from the previous estimate of Chun et al. (2009), who determined the V. cholerae core genome to contain 2,432 gene families based on 23 strains, a higher core genome size than we obtained from our data set. The reduced core genome size is expected as the number of shared genes decreases with the addition of each new genome (Tettelin et al. 2005). It also depends on the degree of relatedness of the organisms. A study on 32 Vibrionaceae genomes, including 18 representative V. cholerae, established a core genome of only 1,000 gene families (Vesth et al. 2010). The V. metoecus pan- and core genomes constitute 4,298 and 2,872 gene families, respectively, based on the ten genomes currently available (supplementary fig. S4b, Supplementary Material online). The difference in pan- and core genome sizes of V. cholerae and V. metoecus can be explained by the significant difference in the number of genomes used. We expect the pan- and core genomes of V. metoecus to ultimately reach sizes similar to that of V. cholerae when genomes of additional strains become available.

As a newly described species, very little is currently known about the biology of V. metoecus and what sets it apart genetically from V. cholerae. From the combined pan-genome of both species, orthologous gene families present in various groups of strains were determined: Families unique to V. metoecus and V. cholerae, or unique to clinical and environmental strains (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). Function was predicted for each gene family based on the COG database (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). Vibrio metoecus contains more unique gene families than V. cholerae that are involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism (supplementary fig. S6a, Supplementary Material online). In the species description study by Kirchberger et al. (2014), it was determined that although the majority of biochemical and growth characteristics of V. metoecus resemble V. cholerae, the former was mainly differentiated from the latter for its ability to utilize the complex sugars d-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine. Indeed, multiple β-galactosidase/β-glucuronidase enzymes for the breakdown of d-glucuronic acid (Louis and Doré 2014) were present in our V. metoecus-specific COG data set, but not in V. cholerae. Multiple hexosaminidases for the hydrolysis of terminal N-acetyl-d-hexosamine (Magnelli et al. 2012) were also detected in V. metoecus, which supports the phenotype observed by Kirchberger et al. (2014). Additionally, genes unique for clinical V. metoecus and clinical V. cholerae were identified (supplementary fig. S6b, Supplementary Material online). Clinical V. cholerae have more genes encoding proteins involved in replication, recombination, and repair (mostly transposases), and signal transduction, such as the GGDEF family protein. Transposases in pathogenicity islands can contribute to the instability and mobilization of virulence genes (Schmidt and Hensel 2004). The GGDEF family protein is critical in biofilm formation (García et al. 2004) and is highly induced in V. cholerae during infection in humans and mice (Lombardo et al. 2007). As expected, genes of the CTX and TCP clusters were not found in our clinical V. cholerae-specific data set because they are not unique to clinical strains, but are also present in some environmental ones (fig. 5a). Among the genes uniquely found in clinical V. metoecus is a putative mdaB (modulator of drug activity B) gene. The mdaB gene has been shown to play an important role in oxidative stress resistance and host colonization in Helicobacter pylori (Wang and Maier 2004), and may also contribute to the fitness of clinical V. metoecus in the host.

Conclusion

The discovery of V. metoecus, the closest known relative of V. cholerae, presents an opportunity to study the HGT events between species and the role this might play in the evolution of pathogenesis. In contrast to the core genome, which is distinctly more similar between members of the same species, the chromosomal integron region, occupying approximately 3% of V. cholerae and V. metoecus genomes, represents a pool of genes which is freely exchanged between these two species. This genomic region displays no greater similarity within than between species. Genomic islands encoding pathogenicity factors, known to play a role in pandemic V. cholerae virulence, are also occasionally found in V. metoecus, either completely or in part. This includes VPI-2, found in most pandemic V. cholerae, as well as the VSP islands, previously believed to be specific to V. cholerae strains from the seventh pandemic. VPI-2 and VSP-2 seem to have assembled over time by accretion of smaller units, which we call islets. Some islets, such as the nan-nag cluster of the VPI-2 (islet B) for sialic acid metabolism, have been stable over time and were present in the common ancestor of V. metoecus and V. cholerae. Other islets, such as islet A (restriction-modification system) and islet D (unknown function) of VPI-2, the core of VSP-2, or the entire VSP-1 island seem to move frequently between V. metoecus and V. cholerae and are not restricted to pandemic strains.

The most striking finding is that even the core genome of V. cholerae is susceptible to frequent interspecies recombination with V. metoecus. Twenty-four percent of the genes found in all V. cholerae and V. metoecus had experienced interspecies recombination. There also seems to be a directional bias to these recombination events. In Oyster Pond, in particular, V. metoecus is the recipient of genes six times more than V. cholerae. The cause of this bias is unclear, but it does not seem to be restricted to a single environment, as all V. metoecus are recipients of more interspecies DNA transfers than any of the V. cholerae strains investigated. One possibility is that V. cholerae is more abundant in most environments than V. metoecus and there is, therefore, simply more of its DNA available for uptake. Indeed, in this study, V. cholerae was isolated ten times more frequently than V. metoecus from Oyster Pond, which is consistent with the observed HGT bias. However, this explanation is very tentative and requires more evidence, as this study is the first one to isolate V. cholerae and V. metoecus quantitatively from the same site, and this was done using a culture-based method. This relative abundance would not necessarily be obtained with more accurate culture-free quantitative methods. Also, HGT could be biased because of differences in phage abundance/susceptibility, presence of DNA uptake systems, or restriction-modification systems. Nonetheless, this is, to our knowledge, the first quantitative report of HGT bias for bacteria in the natural environment and has fundamental implications for understanding the evolution of microbial populations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures S1–S6 and tables S1–S6 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of Tania Nasreen, Paul Stothard (University of Alberta), Lee Katz, Mike Frace, Maryann Turnsek (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), Éric Bapteste (Université Pierre et Marie Curie), Gary Van Domselaar, and Aaron Petkau (National Microbiology Laboratory). They appreciate the helpful discussions with Rebecca Case, Stefan Pukatzki, and David Wishart (University of Alberta). This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (to Y.B.), and the Alberta Innovates—Technology Futures (to F.D.O. and P.C.K.).

Literature Cited

- Ali M, et al. 2012. The global burden of cholera. Bull World Health Organ. 90:209–218A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, et al. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyhan S, Yildiz FH. 2007. Smooth to rugose phase variation in Vibrio cholerae can be mediated by a single nucleotide change that targets c-di-GMP signalling pathway. Mol Microbiol. 63:995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M, Schoolnik GK. 2008. The extracellular nuclease Dns and its role in natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 190:7232–7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y, et al. 2011. Local mobile gene pools rapidly cross species boundaries to create endemicity within global Vibrio cholerae populations. MBio 2:e00335–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y, Labbate M, Koenig JE, Stokes HW. 2007. Integrons: mobilizable platforms that promote genetic diversity in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 15:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choopun N. 2004. The population structure of Vibrio cholerae in Chesapeake Bay [Ph.D. thesis]. [College Park (MD)]: University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, et al. 2009. Comparative genomics reveals mechanism for short-term and long-term clonal transitions in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106:15442–15447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collis CM, Hall RM. 1995. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 39:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BR, et al. 1981. Characterization of biochemically atypical Vibrio cholerae strains and designation of a new pathogenic species, Vibrio mimicus. J Clin Microbiol. 14:631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz F, Davies J. 2000. Horizontal gene transfer and the origin of species: lessons from bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 8:128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J. 2004. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2:414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziejman M, et al. 2002. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae: genes that correlate with cholera endemic and pandemic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99:1556–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S, Herron JC. 2007. Evolutionary analysis. San Francisco (CA): Pearson Benjamin Cummings. [Google Scholar]

- Gaasbeek EJ, et al. 2009. A DNase encoded by integrated element CJIE1 inhibits natural transformation of Campylobacter jejuni. J Bacteriol. 191:2296–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García B, et al. 2004. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 54:264–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge F, Wang LS, Kim J. 2005. The cobweb of life revealed by genome-scale estimates of horizontal gene transfer. PLoS Biol. 3:e316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gil B, et al. 2014. The family Vibrionaceae. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, editors. The prokaryotes—gammaproteobacteria. Berlin (Germany): Springer; p. 659–747. [Google Scholar]

- Goris J, et al. 2007. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 57:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JR, Arantes AS, Stothard P. 2012. Comparing thousands of circular genomes using the CGView Comparison Tool. BMC Genomics 13:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley BJ, et al. 2010. Comparative genomic analysis reveals evidence of two novel Vibrio species closely related to V. cholerae. BMC Microbiol. 10:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan NA, et al. 2010. Comparative genomics of clinical and environmental Vibrio mimicus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:21134–21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg JF, et al. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ. 1993. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst Biol. 42:182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N, Guérout AM, Krin E, Le Roux F, Mazel D. 2015. Comprehensive functional analysis of the 18 Vibrio cholerae N16961 toxin-antitoxin systems substantiates their role in stabilizing the superintegron. J Bacteriol. 197:2150–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermyn WS, Boyd EF. 2002. Characterization of a novel Vibrio pathogenicity island (VPI-2) encoding neuraminidase (nanH) among toxigenic Vibrio cholerae isolates. Microbiology 148:3681–3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaolis DK, Somara S, Maneval DR, Jr, Johnson JA, Kaper JB. 1999. A bacteriophage encoding a pathogenicity island, a type-IV pilus and a phage receptor in cholera bacteria. Nature 399:375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LS, et al. 2013. Evolutionary dynamics of Vibrio cholerae O1 following a single-source introduction to Haiti. MBio 4:e00398–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, et al. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, et al. 2004. Brucella abortus nicotinamidase (PncA) contributes to its intracellular replication and infectivity in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 234:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchberger PC, et al. 2014. Vibrio metoecus sp. nov., a close relative of Vibrio cholerae isolated from coastal brackish ponds and clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 64:3208–3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JE, et al. 2008. Integron-associated gene cassettes in Halifax Harbour: assessment of a mobile gene pool in marine sediments. Environ Microbiol. 10:1024–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. 2005. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102:2567–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille MG, Brinkman FS. 2009. IslandViewer: an integrated interface for computational identification and visualization of genomic islands. Bioinformatics 25:664–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. 2003. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13:2178–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MJ, et al. 2007. An in vivo expression technology screen for Vibrio cholerae genes expressed in human volunteers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:18229–18234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis P, Doré J. 2014. Functional metagenomics of human intestinal microbiome β-glucuronidase activity. In: Nelson KE, editor. Encyclopedia of metagenomics. New York: Springer; p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Magnelli P, Bielik A, Guthrie E. 2012. Identification and characterization of protein glycosylation using specific endo- and exoglycosidases. Methods Mol Biol. 801:189–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur J, Waldor MK. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae ToxR-regulated porin OmpU confers resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun. 72:3577–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D. 2006. Integrons: agents of bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 4:608–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel D, Dychinco B, Webb VA, Davies J. 1998. A distinctive class of integron in the Vibrio cholerae genome. Science 280:605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterchuk MV, Sergiev PV, Dontsova OA. 2011. Posttranslational modifications of ribosomal proteins in Escherichia coli. Acta Naturae 3:22–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea YA, et al. 2004. The Vibrio seventh pandemic island-II is a 26.9 kb genomic island present in Vibrio cholerae El Tor and O139 serogroup isolates that shows homology to a 43.4 kb genomic island in V. vulnificus. Microbiology 150:4053–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrack B, Greengard P, Craston A, Sheppy F. 1965. Nicotinamide deamidase from mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 240:1725–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano D, Schuhmacher DA, Barker JL, Klose KE. 2000. The virulence regulatory protein ToxR mediates enhanced bile resistance in Vibrio cholerae and other pathogenic Vibrio species. Infect Immun. 68:1491–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser JE, et al. 2003. A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol Microbiol. 48:753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.1.2. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed SM, et al. 2012. Genetic characteristics of drug-resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 causing endemic cholera in Dhaka, 2006-2011. J Med Microbiol. 61:1736–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid MU, et al. 2015. ctxB1 outcompetes ctxB7 in Vibrio cholerae O1, Bangladesh. J Med Microbiol. Advance Access published October 19, 2015; doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko DA, Myers GS, Ravel J. 2005. Visualization of comparative genomic analyses by BLAST score ratio. BMC Bioinformatics 6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. 2009. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106:19126–19131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B. 1999. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein Eng. 12:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe-Magnus DA, Mazel D. 2002. The role of integrons in antibiotic resistance gene capture. Int J Med Microbiol. 292:115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samant S, et al. 2008. Nucleotide biosynthesis is critical for growth of bacteria in human blood. PLoS Pathog. 4:e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep K, Lopez P, Lapointe FJ, Bapteste É. 2011. Harvesting evolutionary signals in a forest of prokaryotic gene trees. Mol Biol Evol. 28:1393–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep KP. 2011. Phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27:592–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Hensel M. 2004. Pathogenicity islands in bacterial pathogenesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 17:14–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed KD, et al. 2014. Evolutionary consequences of intra-patient phage predation on microbial populations. Elife 3:e03497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N, Börnigen D, Morgan XC, Huttenhower C. 2013. PhyloPhlAn is a new method for improved phylogenetic and taxonomic placement of microbes. Nat Commun. 4:2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 1997. Cyclic AMP and its receptor protein negatively regulate the coordinate expression of cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94:265–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes HW, Hall RM. 1989. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 3:1669–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szamosi JC. 2012. ISAAC: an improved structural annotation of attC and an initial application thereof [M.Sc. thesis]. [Hamilton (ON)]: McMaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. 2000. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:33–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taviani E, et al. 2010. Discovery of novel Vibrio cholerae VSP-II genomic islands using comparative genomic analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 308:130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RK, Miller VL, Furlong DB, Mekalanos JJ. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 84:2833–2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, et al. 2005. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102:13950–13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernikos G, Medini D, Riley DR, Tettelin H. 2015. Ten years of pan-genome analyses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 23:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesth T, et al. 2010. On the origins of a Vibrio species. Microb Ecol. 59:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Maier RJ. 2004. An NADPH quinone reductase of Helicobacter pylori plays an important role in oxidative stress resistance and host colonization. Infect Immun. 72:1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, et al. 2014. PanGP: a tool for quickly analyzing bacterial pan-genome profile. Bioinformatics 30:1297–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.