Abstract

Parainfluenza viral infections are increasingly recognized as common causes of morbidity and mortality in cancer patients, particularly in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients and hematologic malignancy (HM) patients because of their immunocompromised status and susceptibility to lower respiratory tract infections. Advances in diagnostic methods, including polymerase chain reaction, have led to increased identification and awareness of these infections. Lack of consensus on clinically significant endpoints, and the small number of patients affected in each cancer institution every year make it difficult to assess the efficacy of new or available antiviral drugs. In this systematic review, we summarized data from all published studies on parainfluenza virus infections in HM patients and HCT recipients, focusing on incidence, risk factors, long-term outcomes, mortality, prevention, and management with available or new investigational agents. Vaccines against these viruses are lacking; thus, infection control measures remain the mainstay for preventing nosocomial spread. A multi-institutional collaborative effort is recommended to standardize and validate clinical endpoints for PIV infections, which will be essential for determining efficacy of future vaccine and antiviral therapies.

Keywords: PIV, stem cell transplant, leukemia, cancer, antiviral therapy, pneumonia

1. INTRODUCTION

Advances in diagnostic methods, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have led to increased identification and awareness of paramyxoviruses. Parainfluenza viruses (PIV) are increasingly recognized as common causes of morbidity and mortality in cancer patients, particularly in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients and hematologic malignancy (HM) patients because of their immunocompromised status. PIV is an enveloped, single-stranded, RNA paramyxovirus; it comprises of four antigens that share serotypes, but most clinical infections are caused by types 1, 2, and 3. A wide range of PIV incidence is reported in HM patients and HCT recipients. PIV type 3 is responsible for up to 90% of infections; it most commonly affects the upper respiratory tract after an incubation period of 1 to 4 days. Clinical manifestations include croup, otitis media, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), bronchitis, pneumonitis, and less frequently, central nervous system infection. One of the most common complications of PIV URTI is progression to lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), which occurs in 20% to 39% of HCT recipients and has an associated mortality rate of up to 30%.[1, 2] Whether treating these infections with available (ribavirin) or investigational (DAS 181) antiviral agents affects progression to pneumonitis or mortality remains unknown.

Many conflicting reports exist about the clinical disease spectrum, management, and overall outcomes of PIV infections in HM patients and HCT recipients. Hence, we conducted a systematic review of all published studies to determine the incidence, risk factors, management, long-term outcomes, and mortality rates associated with PIV infections in HM patients and HCT recipients. Advances in diagnostic methods, available or new investigational drugs, and vaccines are also discussed.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted an electronic literature search using Medline via the Ovid, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane library databases in September 2015. The following Medical Subject Heading terms were used: human parainfluenza virus 1, human parainfluenza virus 2, human parainfluenza virus 3, human parainfluenza virus 4, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, bone marrow transplantation, leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and hematologic neoplasms. The references in all of the selected studies were also reviewed to identify additional articles that did not appear in the initial search. The full texts of the selected articles were reviewed by all the authors. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined a priori.

Inclusion criteria selecting the articles were:

HM patients and HCT recipients of any age and had been infected with laboratory diagnosed PIV infection,

Retrospective or prospective observational studies and randomized controlled trials, if any, and

No time restriction for the study period.

Articles in English

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies not focusing on PIV infections in HM patients or HCT recipients,

Review papers or meta-analyses,

Case reports of 10 patients or less

Meeting abstracts

Studies with duplicate data or incomplete information, and

We also searched the Clinical Trials registry (U.S. National Institutes of Health, www.clinicaltrials.gov) to identify any registered clinical trials for PIV infections.

2.2. Definitions

PIV infections and subsequent outcomes were ascertained by the authors of the original articles using various definitions; however, below are the summarized versions of these definitions used for the current review.

PIV case: patients with a positive nasal wash, nasopharyngeal swab, or bronchoalveolar lavage for PIV by one of the viral diagnostic tests (viral culture, direct immunofluorescence testing, or PCR) were included in this review.

PIV-LRTI: was defined as the onset of respiratory symptoms with new or changing pulmonary infiltrates, as seen on chest x-ray or CT scan of chest and/or virus isolated from lower respiratory samples (e.g., endotracheal tube aspirate, sputum, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid)

PIV-mortality: Death was attributed to PIV if a persistent or progressive infection with respiratory failure was identified at the time of death.

2.3. Data abstraction

Two authors (D.P.S. and P.K.S.) independently screened the abstracts using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Three authors (D.P.S., P.K.S. and J.M.A.) used standardized coding rules to abstract important variables from the final list of articles independently and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Primary variables of interest for this study were incidence of PIV infection, progression of PIV-URTI to PIV-LRTI and PIV-associated mortality. Antiviral therapy included ribavirin (aerosolized, intravenous, or oral) alone or in combination with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Effect of antiviral therapy was measured by comparing incidence rates of these outcomes in treated and untreated patients. Outcome data from selected full-text articles were validated by R.F.C. For studies reporting outcomes in HM patients and HCT recipients, the data abstraction was split into two parts to capture the characteristics and outcomes of each group, respectively.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Agreement between the two independent authors in the first and second phase of the full-text selection process was checked by calculating Cohen's Kappa. Outcomes (i.e., LRTI progression and death) were descriptively summarized as percentages. We compared treated and untreated patient outcomes using Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Forest plot was constructed to demonstrate the significant risk factors associated with acquiring PIV infection, PIV-LRTI and PIV-mortality using adjusted odds ratios from published studies. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 13 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

We reviewed 441 abstracts on PIV infections in HM patients or HCT recipients. Of these, 274 were not specific to PIV infection or the pre-defined population or focus of the study. Of the remaining 167 abstracts, 101 were excluded from further review (49 were review studies on respiratory viruses, 12 were outbreak investigations, 24 were case reports with ≤ 10 patients, and 16 had overlapping data with an included study, had incomplete information, or were meeting abstracts); thus, we included 66 full-text articles. Twenty one studies measured the incidence of respiratory viruses in HM patients or HCT recipients and 11 studies provided primary data for LRTI risk factors and management and mortality, including antiviral therapy effects; thus, data were abstracted for PIV incidence, PIV-LRTI, and associated mortality. Furthermore, we reviewed studies that evaluated new diagnostic methods (9) and investigational new drugs (4); long-term outcomes such as airflow obstruction (6); prophylaxis (2); and pathophysiologic and immunogenetic factors (14). (A detailed flowchart of the abstract screening process is shown in Supplemental Figure S1). The agreement between the two authors during the selection of abstracts and the selection of full-texts, as measured by Cohen's Kappa, was 0.903 [95% CI: 0.862 – 0.945] and 0.926 [0.867 – 0.984], respectively which is regarded as substantial to excellent.

3.1 Incidence of PIV Infections

A total of 32 studies were reviewed, including 2 studies [1, 3] that were divided into two parts to stratify information on HM patients and HCT recipients. Majority of the studies did not provide the breakdown for the type of HM for their study population; however, we observed that the most common HM for children was acute lymphoblastic leukemia (>60%). This information was not available for studies with adult patients.The incidence of PIV infections is displayed in Table 1. We identified 1196 PIV infections in 31,730 patients, giving an incidence of 4%, with a wide range of 0.2% to 30%. The reported incidence of PIV infections in HCT recipients (4% [838 of 21,062]) was significantly higher than that in HM patients (2% [246 of 9,685]) (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4, 1.8; P value<0.0001). Furthermore, a significantly higher PIV infection rate was reported in allogeneic HCT recipients (5% [482 of 10,147]) than in autologous HCT recipients (3% [206 of 7365]) (OR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.46, 2.05; P value<0.0001).

Table 1.

Incidence of PIV infections, lower respiratory tract infection, and PIV-associated mortality in HCT recipients and HM patients, n (%)

| Author | Years of infection |

Location | Study popula tion |

Age | Surveil lance |

Diagnosis | PIV incid ence |

PIV- LRTI |

PIV- associat ed mortalit y |

LRTI related deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT recipients | ||||||||||

| Wasserman, 1988[33] |

Jan 1979 - Jul 1986 |

Philadelphi a, PA |

96 | Children | S | Culture | 5 (5) | 1 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Lujan- Zilbermann, 2001[34] |

Jan 1994 - Dec 1997 |

Memphis, TN |

274 | Children | S | Culture, DFA |

17 (6) | 7 (41) | 1 (6) | 1 (14) |

| Srinivasan, 2011[6] |

Jan 1995 - Dec 2009 |

Memphis, TN |

738 | Children | S | Culture, DFA, PCR |

46 (6) | 18 (39) |

6 (13) | 6 (33) |

| Fazekas-A, 2012[3] |

Nov 2007 - Feb 2009 |

Vienna, Austria |

31 | Children | AS | RT-PCR | 1 (3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Lee, 2012[35] | Jan 2007- Aug 2009 |

Seoul, Korea |

176 | Children | S | Culture, PCR |

1 (0.5) |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| Choi, 2013[36] | Jan 2007 - Mar 2010 |

Seoul, Korea |

358 | Children | S | PCR | 22 (6) | 8 (36) | 1 (5) | 1 (13) |

| Srinivasan-A, 2013[37] |

Oct 2010 - Sep 2011 |

Memphis, TN |

42 | Children | S | PCR | 6 (14) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 1 (33) |

| Lewis, 1996[8] | Jan 1991 - Sep 1994 |

Houston, TX |

1173 | Adult | S | Culture, IIF |

61 (5) | 27 (44) |

10 (16) | 10 (37) |

| Whimbey, 1996[38] |

Nov 1992 - May 1993; Nov 1993 - May1994 |

Houston, TX |

217 | Adult | S | Culture | 6 (3) | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Williamson, 1999[39] |

Jun 1990 - Jun 1997 |

Bristol, UK | 60 | Adult | S | DFA | 9 (15) | 4 (44) | 0 | 0 |

| Chakrabarti, 2002[2] |

Jun 1997 - Aug 2001 |

Birmingha m, UK |

83 | Adult | S | Culture, DFA |

16 (19) |

13 (81) |

2 (13) | 2 (15) |

| Roghmann, 2003[40] |

Jan 2001-Apr 2001 |

Baltimore, MD |

62 | Adult | AS | Culture, PCR |

5 (8) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hassan, 2003[41] |

May 1996 - May 2001 |

Manchester , UK |

626 | Adult | S | Culture, Rapid Ag test |

4 (1) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (50) |

| Martino, 2005[42] |

Sep 1999 - Oct 2003 |

Barcelona, Spain |

386 | Adult | S | IIF, culture |

8 (2) | 3 (38) | 0 | 0 |

| Dignan, 2006[43] |

Jul 2004- Jun 2005 |

Surrey, UK | 145 | Adult | AS | Culture, DIF |

24 (14) |

12 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (8) |

| Schiffer, 2009[44] |

Dec1997- Mar2005 |

Seattle, WA |

2,901 | Adult | S | Culture, DFA |

122 (4) |

27 (1) | 13 (11) | 13 (46) |

| Chemaly-A, 2012[1] |

Oct 2002 - Nov 2007 |

Houston, TX |

3473 | Adult | S | DFA, Culture |

120 (3) |

46 (38) |

8 (7) | 8 (17) |

| Ljungman, 1989[45] |

Jan 1987-Apr 1987 |

Seattle, WA |

78 | Any | AS | Culture, IIF |

8 (10) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Wendt, 1992[20] |

Mar 1974 - Apr 1990 |

Minneapoli s, MN |

1253 | Any | S | Culture | 27 (2) | 19 (70) |

6 (22) | 6 (32) |

| Elizaga, 2001[28] |

Jan 1990 - Sep 1996 |

London, UK |

456 | Any | S | Culture, IIF |

26 (6) | 14 (54) |

8 (31) | 8 (57) |

| Nichols, 2001[9] |

Jul 1990 - Jun 1999 |

Seattle, WA |

3577 | Any | S | Culture, DFA |

253 (7) |

56 (22) |

19 (8) | 19 (34) |

| Ljungman, 2001[46] |

Oct 1997 - Sep 1998 |

37 EBMT centers, Europe |

1973 | Any | S | Culture, IIF, ELISA |

4 (0.2) |

1 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Crippa, 2002[47] |

Apr 1995 - Nov 1998 |

Seattle, WA |

305 | Any | S | Culture, DFA, |

13 (4) | 6 (46) | NA | NA |

| Machado, 2003[48] |

Apr 2001 - Apr 2002 |

Sao Paulo, Brazil |

179 | Any | S | DFA | 12 (7) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Raboni, 2003[49] |

Mar 1993 - Aug 1999 |

Parana, Brazil |

722 | Any | S | IIF | 7 (1) | 2 (29) | 2 (29) | 2 (100) |

| Peck, 2007[27] | Dec 2000 - Jun 2004 |

Seattle, WA |

122 | Any | AS | Culture, DFA, PCR |

17 (14) |

2 (12) | 1 (6) | 1 (50) |

| Ustun, 2012[5] |

Jan 1974 - Dec 2010 |

Minneapoli s, MN |

5178 | Any | S | Culture | 173 (3) |

75 (43) |

32 (18) | 32 (43) |

|

| ||||||||||

| HM patients | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Craft, 1979[50] | 1979-1981 | UK | 64 | Children | S | FAT, culture |

4 (6) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (50) |

| Mottonen, 1995[51] |

Nov 1987 - Dec 1989 |

Oulu, Finland |

62 | Children | AS | Culture, EIA, serum antibody (CF) |

12 (19) |

0 | NA | NA |

| Srinivasan, 2011[7] |

Jan 2000 - Dec 2009 |

Memphis, TN |

820 | Children | S | Culture, DFA, PCR |

83 (10) |

17 (20) |

0 | 0 |

| Fazekas-B, 2012[3] |

Nov 2007 - Feb 2009 |

Vienna, Austria |

103 | Children | AS | PCR | 4 (4) | NA | NA | NA |

| Srinivasan-B, 2013[37] |

Oct2010- Sep2011 |

Memphis, TN |

121 | Children | S | PCR | 16 (13) |

1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Marcolini, 2003[10] |

Jul 1994 - Dec 1997 |

Houston, TX |

770 | Adult | S | Culture | 47 (6) | 26 (55) |

7 (15) | 7 (27) |

| Chemaly-B, 2012[1] |

Oct 2002 - Nov 2007 |

Houston, TX |

7745 | Adult | S | DFA, Culture |

80 (1) | 49 (61) |

8 (10) | 8 (16) |

|

| ||||||||||

| HCT recipients and HM patients | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Martino, 2003[52] |

Oct 1999 - May 2001 |

Barcelona, Spain |

130 | Adult | S | DFA, culture |

8 (6) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (100) |

| Park, 2013[53] | Jan 2009-Feb 2012 |

Seoul, Korea |

737 | Adult | S | PCR, DFA | 64 (9) | NA | 7 (11) | NA |

| Chemaly, 2006[54] |

Jul 2000 - Jun 2002 |

Houston, TX |

306 | Adult | S | Culture, Rapid Ag test |

92 (30) |

34 (37) |

4 (4) | 4 (12) |

| Couch, 1997[55] |

1992-1995 | Houston, TX |

668 | Any | S | culture | 28 (4) | NA | NA | NA |

S indicates symptomatic; AS, asymptomatic; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; DFA, direct fluorescent antibody; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; FAT, fluorescent antibody technique; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; PIV, parainfluenza virus; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; NA, not available.

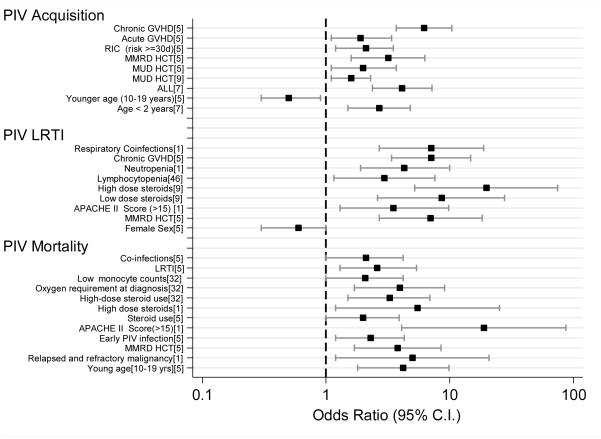

The significant risk factors for acquiring PIV infections in HCT recipients and HM patients are displayed in Figure 1. Adults who underwent HCT from a matched unrelated donor or mismatched related donor had a significantly higher risk of PIV infection than did those who underwent matched related or autologous HCT.[4, 5] Similarly, children who underwent allogeneic HCT or total body irradiation were more likely to acquire symptomatic infections, when adjusted for other variables.[6] In children with HM, age less than 2 years (OR: 2.69, 95% CI: 1.5-4.8) and having ALL rather than other malignancies (OR: 4.13, 95% CI: 2.37-7.21) were significant risk factors for PIV infections.[7]

Figure 1.

Risk factors significantly associated with PIV infection, PIV-LRTI and PIV-mortality in HCT recipients and HM patients

3.2 PIV-LRTI

The incidence of PIV-LRTI in HM patients and HCT recipients, as reported in 28 studies, is shown in Table 1. We identified 428 PIV-LRTI cases among 1163 PIV infections, giving an incidence of 37% for all studies combined (range, 0% to 74%). Stratified by underlying condition, PIV-LRTI was observed in 95 of 246 HM patients (39%) and 299 of 837 HCT recipients (36%) with PIV infections. PIV-LRTI incidence information was not available for different types of HCT.

The risk factors for PIV-LRTI are shown in Figure 1. In brief, allo-HCT,[5, 8] especially infection within 100 days after HCT,[6] lymphocytopenia,[6, 7] neutropenia at the onset of infection,[1, 6, 7] use of corticosteroids during PIV-URTI,[6, 9] and respiratory co-infections[1, 10] were significant predictors of LRTI progression.

3.3 PIV-associated mortality

Twenty six studies reported PIV-associated mortality in HM patients and HCT recipients (Table 1). This rate varied greatly, ranging from 0% to 31%, with a total of 117 PIV-deaths in 1138 PIV infected patients (10%). It was not significantly different in HCT recipients (12% [96 of 826]) than in HM patients (7% [16 of 230]); OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.0, 3.3; P value = 0.05). However, significantly higher mortality rate was observed in patients with PIV-LRTI (27% [117 of 428]; OR: 3.3, 95% CI: 2.4, 4.4, P value<0.0001), irrespective of the underlying condition.

PIV-LRTI has been found to be a major risk factor for PIV-associated mortality in both HM patients and HCT recipients, irrespective of age.[5, 6, 10] Other risk factors are displayed in Figure 1 and include lymphocytopenia,[6, 10] younger age,[5] allo-HCT or mismatched related allo-HCT,[5, 8] refractory or relapsed underlying malignancy,[1] APACHE II score > 15,[1] respiratory co-infections,[5] and steroid use at infection onset.[1, 5, 6] (Supplemental Table S1)

3.4 Other outcomes

Late-onset non-infectious pulmonary complications after respiratory infections included diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, idiopathic pneumonia syndrome, bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), and bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia. Many studies have implicated respiratory viruses in the development of BO in HCT recipients. One study demonstrated that PIV infection independently increases the risk of airflow decline, which was immediately detectable after infection in HCT recipients.[11] On the other hand, another study found no association between respiratory viral infection and BO development in HCT recipients.[12] Hence, studies in HCT recipients or HM patients are needed to systematically estimate the incidence of BO after respiratory infections, identify associated risk factors, and test preventive strategies when applicable.

3.5 Diagnosis

Clinically, PIV infections cannot be differentiated from other respiratory viruses in immunocompromised patients; therefore, diagnosis is dependent on laboratory confirmation. Several laboratory methods, such as rapid antigen testing, enzyme immunoassays, real-time PCR, and viral cultures, have been used to diagnose PIV infections.[13-15] A recent study reported that the PCR technique was two and four times as sensitive as culture and fluorescence antigen detection assays, respectively, at detecting respiratory viruses, especially PIV.[16] High-resolution CT of the chest has been reported to aid in diagnosing respiratory viral infections in HCT recipients; however, caution should be exercised in interpreting the results because of the considerable overlap between the imaging appearances of bacterial and viral pneumonia.[17, 18] Similar to most viral pneumonias, PIV-LRTI can range from mild scattered to scattered centrilobular nodules (predominantly in the upper lobes) to patchy ground-glass opacities on high-resolution CT.[19] A lung biopsy may reveal giant-cell pneumonia, intra-cytoplasmic viral inclusions, and interstitial pneumonia, consistent with PIV-LRTI;[8, 20] however, lung biopsies are seldom performed to establish the diagnosis.

3.6 Antiviral therapy

Ten retrospective studies reported the use of antiviral therapy for PIV infections, including 8 in HCT recipients and 2 in HM patients. Most of these studies found that ribavirin was not significantly effective at preventing PIV-LRTI or PIV-associated mortality; however, therapy was mainly administered to patients with LRTI. In fact, the PIV-associated mortality rate was slightly higher in patients treated with ribavirin-based therapy at the LRTI stage (34% [37 of 108]) than in those who were not treated (25% [49 of 193]), which could be explained by a selection bias for treating sicker patients (Table 2). Information on the use of ribavirin at the URTI stage was only available from 6 studies in HCT recipients and HM patients. LRTI progression was not significantly different in HCT recipients who were treated with ribavirin-based therapy at the URTI stage (35% [8 of 23]) and those who were not treated (46% [118 of 256]) (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.22, 1.64; P value=0.296). Similarly, no significant difference in PIV-associated mortality was observed for HCT recipients who were treated at the URTI stage and those who were not treated (0% [0 of 23] versus 11% [28 of 256]; P value=0.094). Among HM patients, only 1 study reported the use of antiviral therapy at the URTI stage; thus, a pooled analysis was not possible. This study did not report any significant reduction in PIV-LRTI or PIV-associated mortality with antiviral therapy at the URTI stage.[1]

Table 2.

Effect of antiviral therapy on PIV-LRTI and PIV mortality in HCT recipients and HM patients, no. (%)

| Author, Year |

PIV cases |

Total treated |

Antiviral therapy |

Treated, URTI stage | Not treated, URTI stage | Treated, LRTI stage | Not treated, LRTI stage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| No. | Progression to LRTI |

Deaths | No. | Progression to LRTI |

Deaths | No. | Deaths | No. | Deaths | ||||

| HCT recipients | |||||||||||||

| Chemaly-A, 2012[1] |

120 | 10 (8) | AR ± IVIG |

5 | 3 (60) | 0 | 115 | 43 (37) | 8 (7) | 5 | 1 (20) | 38 | 7 (18) |

| Chemaly, 2006[54] |

92 | 23 (25) | AR | 7 | 4 (57) | 0 | 85 | 30 (35) | 4 (5) | 16 | 2 (13) | 18 | 2 (11) |

| Wendt, 1992[20] |

27 | 9 (33) | AR | 2 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 19 (76) | 6 (24) | 7 | 2 (29) | 12 | 4 (33) |

| Chakrabarti, 2002[2] |

16 | 14 (88) | AR or IR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 13 (87) | 2 (13) | 13 | 2 (15) | 0 | 0 |

| Elizaga, 2001[28] |

24 | 18 (75) | AR | 8 | 1 (13) | 0 | 16 | 13 (81) | 8 (50) | 10 | 6 (60) | 4 | 2 (50) |

| Ustun, 2012[5] |

173 | 51 (29) | AR ± IVIG |

10 | - | - | 163 | - | - | 41 | 19 (46) | 34 | 13 (38) |

| Lujan- Zilberman, 2001[34] |

17 | 3 (18) | AR | 0 | - | - | 17 | - | - | 3 | 1 (33) | 4 | 0 |

| Lewis, 1996[8] |

61 | 5 (8) | AR | 0 | - | - | 61 | - | - | 5 | 2 (40) | 22 | 8 (36) |

| Dignan, 2006[43] |

23 | 8 (35) | AR or IR | 2 | - | 0 | 15 | - | 1 (6) | 6 | 1 (17) | 6 | 2 (33) |

| Total | 553 | 141 (25) |

35 | 8 (23) | 0 | 512 | 118 (23) | 28 (5) | 106 | 36 (34) | 138 | 38 (28) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| HM patients | |||||||||||||

| Chemaly-B, 2012[1] |

80 | 9 (11) | AR ± IVIG |

6 | 6 (100) | 1 (17) | 74 | 43 (58) | 7 (9) | 3 | 1 (33) | 40 | 7 (18) |

| Marcolini, 2003[10] |

47 | 5 (11) | AR | 0 | - | - | 47 | - | - | 5 | 1 (20) | 21 | 6 (29) |

|

Total for all

studies combined |

680 | 155 (23) |

41 | 14 (34) | 1 (2) | 633 | 161 (25) | 35 (6) | 114 | 8 (7) | 199 | 51 (26) | |

AR, aerosolized ribavirin; IR, intravenous ribavirin; and IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

3.7 Investigational drugs

Because no commercially available antiviral agent exists for PIV, novel drugs such as DAS181 (a recombinant sialidase fusion protein)[21] and BCX2798 (a hemagglutinin-neuraminidase inhibitor)[22] are being evaluated (Supplemental Table S2). DAS181 enzymatically removes sialic acid moieties to temporarily disable PIV receptors in the airway epithelium.[23] DAS181 has shown efficacy against PIV in vitro, in a cotton rat infection model, and in three immunocompromised patients with respiratory infections, including two HCT recipients.[21, 23, 24] Other compounds, such as BCX2798 and BCX2855, have been found to have antiviral activity against PIV-3, significantly reducing pulmonary viral titers and mortality in rats when given intranasally within 24 hours of infection;[22] however, no human studies are available. Given the significant mortality rate associated with PIV-LRTI in immunocompromised patients, there is an unmet need for managing these infections. Data on the efficacy and cost-benefit of these compounds in this vulnerable population are needed.

Given the significant morbidity and mortality of PIV infections, there has been substantial interest in developing an effective vaccine over the past few years. Many clinical trials (phase I or II studies) are being conducted to test vaccine efficacy against PIV in healthy infants or children (Supplemental Table S3). Interestingly, mucosal immunization has been suggested as a promising alternative vaccination strategy because of recent advances in delivery systems and improved knowledge about site-specific mucosal immune mechanisms.[25] However, the protective potential of active immunizations in immunocompromised patients is usually suboptimal.

In the absence of an effective therapy or vaccine, infection control measures such as contact isolation, hand hygiene, and masks and gloves, along with universal precautions, are the mainstay for preventing the spread of PIV in HCT recipients and HM patients. Viral shedding after infection, especially in asymptomatic patients, may be a key factor in propagating this virus in the immunocompromised population. The results of a recent study suggested that a long duration of viral shedding and “ping-pong” transmission between patients and healthcare personnel or caregivers may be responsible for periodic community-wide and nosocomial outbreaks.[26] Furthermore, asymptomatic or subclinical PIV infections have been well documented in HCT recipients and HM patients. Thus, subclinical infection, along with prolonged duration of viral shedding, may explain the failure of infection control practices in containing the transmission of this virus, unlike respiratory syncytial virus and influenza.[27]

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we attempted to assemble all published data on PIV infections in HM patients and HCT recipients to generate meaningful conclusions about their incidence, LRTI and mortality rates, long-term outcomes, management (including antiviral therapy and new investigational drugs), and prevention measures, including vaccines.

We identified high rates of PIV infection in HM patients and HCT recipients. The incidence varied widely, which could be attributed to factors such as patient sampling methods, patient age, transplant and underlying malignancy type, season and study period, publication bias, and diagnostic method used (i.e., RT-PCR vs. direct fluorescence antigen assay vs. culture). Over the past few decades, the number of reported PIV infections increased because of increased awareness and increased availability of fast, inexpensive, reliable diagnostic methods.

Further, we observed high morbidity and mortality rates after these infections with 37% rate of progression to LRTI and 10% virus-associated mortality rates following PIV infections. High mortality rate following progression to LRTI (27%) was observed. Additionally, we observed no differences in LRTI or mortality rates between HM patients and HCT recipients following PIV infections. This finding was not shared by other studies of both populations, in which PIV-LRTI was more common in HM patients than in HCT recipients.[1]

Similar risk factors for PIV-LRTI were consistently identified in many studies, which may help clinicians identify high-risk patients. Lymphocytopenia,[6, 7] neutropenia,[1, 6, 7] and corticosteroid usage[6, 9] were significantly associated with PIV-LRTI; however, we could not abstract primary data for these risk factors to conduct a pooled analysis. Other variables such as age,[7] type of transplant (allo-HCT vs. auto-HCT)[8], and time from HCT[6] were inconsistently reported as risk factors for PIV-LRTI; however some studies found no such association.[1, 20, 28]

Ribavirin has had promising results against PIV in animal models and children with severe combined immunodeficiency.[29, 30] Large case series have demonstrated that it has no effect on viral shedding, symptom duration, hospital stay duration, PIV-LRTI progression, or mortality in HCT recipients,[1, 2, 20] with the caveat that in most published studies, it was used in patients that had already experienced progression to LRTI. We hypothesized that the time of initiation of ribavirin-based therapy might affect outcomes but based on our pooled analysis of ribavirin used at the URTI stage, it did not affect the LRTI progression or mortality rate significantly. Randomized trials are needed to evaluate ribavirin’s effects at the URTI stage to prevent LRTI progression and mortality in this patient population. Although active against PIV in vitro,[31] ribavirin’s role in treating PIV infections in HCT recipients and HM patients is still not known. In the absence of an effective drug or vaccine, infection control measures remain the mainstay in preventing these infections and any subsequent morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.

There are many limitations of this systematic review. One limitation is that we only reviewed studies published in English; thus, we missed many publications from other countries, especially developing nations. In addition, our reliance on secondary data may be subject to interpretation errors; we tried to minimize this by having three different investigators (D.P.S., P.K.S. and J.M.A.) validate the data; and outcomes were reconfirmed by R.F.C. Most of the studies were retrospective and non-randomized in nature; hence, the results of this systematic review should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the majority of the studies did not report the breakdown for the type of HM for their study population or the details on the type of PIV infection, hence we could not further analyze these variables. Finally, since this review included a heterogeneous study population, we could not conduct a meta-regression analyses to identify the independent effects of various host risk factors on the progression to LRTI. We attempted to decrease the publication bias by including almost all published studies with minimal exclusion criteria. Another limitation of these studies was the lack of standardized definition for PIV-LRTI. As reported in a recent study in HCT recipients, 90-day survival probabilities were significantly different between possible, probable, and proven LRTI based on univariable regression analysis.[32] We propose a multi-institutional collaborative effort to standardize and validate clinical endpoints for PIV infections, which will be essential for determining efficacy of future vaccine and antiviral therapies.

In summary, to our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review on PIV infections in HM patients and HCT recipients examining the incidence, risk factors, morbidity, mortality, diagnosis, and management limitations, and the importance of prevention in decreasing nosocomial spread.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

First systematic review on PIV infections in HM patients and HCT recipients

PIV Incidence, risk factors, morbidity, and mortality reviewed from all published studies

Data on antiviral therapy, ongoing clinical trials and vaccine trials are also examined

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to our librarian, Ms. Yimin Geng, The University of Texas MD Anderson Research Medical Library for her assistance with electronic search for this review. We also thank Ms. Ann Sutton, Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for her editorial support.

FUNDING SUPPORT

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.P.S. and R.F.C. designed the study, D.P.S., P.K.S. screened the abstracts; D.P.S., P.K.S. and J.M.A. extracted data from full text articles, D.P.S and R.F.C. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed the full text articles and provided critical feedback and ?nal approval for the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R.F.C received research grant from Ansun pharmaceuticals. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- [1].Chemaly RF, Hanmod SS, Rathod DB, Ghantoji SS, Jiang Y, Doshi A, Vigil K, Adachi JA, Khoury AM, Tarrand J, Hosing C, Champlin R. The characteristics and outcomes of parainfluenza virus infections in 200 patients with leukemia or recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:2738–2745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-371112. quiz 2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chakrabarti S, Avivi I, Mackinnon S, Ward K, Kottaridis PD, Osman H, Waldmann H, Hale G, Fegan CD, Yong K, Goldstone AH, Linch DC, Milligan DW. Respiratory virus infections in transplant recipients after reduced-intensity conditioning with Campath-1H: high incidence but low mortality. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;119:1125–1132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fazekas T, Eickhoff P, Rauch M, Verdianz M, Attarbaschi A, Dworzak M, Peters C, Hammer K, Vecsei A, Potschger U, Lion T. Prevalence and clinical course of viral upper respiratory tract infections in immunocompromised pediatric patients with malignancies or after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2012;34:442–449. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182580bc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Garrett Nichols W, Corey L, Gooley T, Davis C, Boeckh M. Parainfluenza virus infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Risk factors, response to antiviral therapy, and effect on transplant outcome. Blood. 2001;98:573–578. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ustun C, Slabý J, Shanley RM, Vydra J, Smith AR, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, Young JA. Human parainfluenza virus infection after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors, management, mortality, and changes over time. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1580–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Srinivasan A, Wang C, Yang J, Shenep JL, Leung WH, Hayden RT. Symptomatic parainfluenza virus infections in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:1520–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Srinivasan A, Wang C, Yang J, Inaba H, Shenep JL, Leung WH, Hayden RT. Parainfluenza virus infections in children with hematologic malignancies. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011;30:855–859. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31821d190f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lewis VA, Champlin R, Englund J, Couch R, Goodrich JM, Rolston K, Przepiorka D, Mirza NQ, Yousuf HM, Luna M, Bodey GP, Whimbey E. Respiratory disease due to parainfluenza virus in adult bone marrow transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;23:1033–1037. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nichols WG, Gooley T, Boeckh M. Community-acquired respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center experience. Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation. 2001;7 Suppl:11S–15S. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11777098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marcolini JA, Malik S, Suki D, Whimbey E, Bodey GP. Respiratory disease due to parainfluenza virus in adult leukemia patients. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2003;22:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Versluys AB, Rossen JW, van Ewijk B, Schuurman R, Bierings MB, Boelens JJ. Strong association between respiratory viral infection early after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the development of life-threatening acute and chronic alloimmune lung syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:782–791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Au BK, Au MA, Chien JW. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome epidemiology after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ray CG, Minnich LL. Efficiency of immunofluorescence for rapid detection of common respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:355–357. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.2.355-357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Osiowy C. Direct detection of respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus in clinical respiratory specimens by a multiplex reverse transcription-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3149–3154. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3149-3154.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fan J, Henrickson KJ, Savatski LL. Rapid simultaneous diagnosis of infections with respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, influenza viruses A and B, and human parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3 by multiplex quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction-enzyme hybridization assay (Hexaplex) Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1397–1402. doi: 10.1086/516357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kuypers J, Campbell AP, Cent A, Corey L, Boeckh M. Comparison of conventional and molecular detection of respiratory viruses in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miller WT, Mickus TJ, Barbosa E, Mullin C, Van Deerlin VM, Shiley KT. CT of Viral Lower Respiratory Tract Infections in Adults: Comparison Among Viral Organisms and Between Viral and Bacterial Infections. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2011;197:1088–1095. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shiley KT, Van Deerlin VM, Miller WT. Chest CT Features of Community-acquired Respiratory Viral Infections in Adult Inpatients With Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 2010;25:68–75. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181b0ba8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kanne JP, Godwin JD, Franquet T, Escuissato DL, Muller NL. Viral pneumonia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: High-resolution CT findings. Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 2007;22:292–299. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31805467f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wendt CH, Weisdorf DJ, Jordan MC, Balfour HH, Jr., Hertz MI. Parainfluenza virus respiratory infection after bone marrow transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:921–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204023261404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen Y-B, Driscoll JP, McAfee SL, Spitzer TR, Rosenberg ES, Sanders R, Moss RB, Fang F, Marty FM. Treatment of parainfluenza 3 infection with DAS181 in a patient after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e77–80. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Alymova IV, Taylor G, Takimoto T, Lin TH, Chand P, Babu YS, Li C, Xiong X, Portner A. Efficacy of novel hemagglutinin-neuraminidase inhibitors BCX 2798 and BCX 2855 against human parainfluenza viruses in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1495–1502. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1495-1502.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Guzman-Suarez BB, Buckley MW, Gilmore ET, Vocca E, Moss R, Marty FM, Sanders R, Baden LR, Wurtman D, Issa NC, Fang F, Koo S. Clinical potential of DAS181 for treatment of parainfluenza-3 infections in transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moscona A, Porotto M, Palmer S, Tai C, Aschenbrenner L, Triana-Baltzer G, Li QX, Wurtman D, Niewiesk S, Fang F. A recombinant sialidase fusion protein effectively inhibits human parainfluenza viral infection in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:234–241. doi: 10.1086/653621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Otczyk DC, Cripps AW. Mucosal immunization: A realistic alternative. Human Vaccines. 2010;6:978–1006. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.12.13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Aliyu ZY, Bordner MA, Henderson DK, Sloand EM, Young NS, Childs R, Bennett J, Barrett J. Low morbidity but prolonged viral shedding characterize parainfluenza virus 3 infections in allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplant recipients. Blood. 2004;104:614A–614A. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Peck AJ, Englund JA, Kuypers J, Guthrie KA, Corey L, Morrow R, Hackman RC, Cent A, Boeckh M. Respiratory virus infection among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: evidence for asymptomatic parainfluenza virus infection. Blood. 2007;110:1681–1688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elizaga J, Olavarria E, Apperley J, Goldman J, Ward K. Parainfluenza virus 3 infection after stem cell transplant: relevance to outcome of rapid diagnosis and ribavirin treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32:413–418. doi: 10.1086/318498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gilbert BE, Knight V. Biochemistry and clinical applications of ribavirin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:201–205. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McIntosh K, Kurachek SC, Cairns LM. Treatment of respiratory viral infection in an immunodeficient infant with ribavirin aerosol. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1984;138:305–308. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140410083024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sidwell RW, Khare GP, Allen LB, Huffman JG, Witkowski JT, Simon LN, Robins RK. In vitro and in vivo effect of 1-beta-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (ribavirin) on types 1 and 3 parainfulenza virus infections. Chemotherapy. 1975;21:205–220. doi: 10.1159/000221861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Seo S, Xie H, Campbell AP, Kuypers JM, Leisenring WM, Englund JA, Boeckh M. Parainfluenza virus lower respiratory tract disease after hematopoietic cell transplant: viral detection in the lung predicts outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1357–1368. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wasserman R, August CS, Plotkin SA. Viral infections in pediatric bone marrow transplant patients. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 1988;7:109–115. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198802000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lujan-Zilbermann J, Benaim E, Tong X, Srivastava DK, Patrick CC, DeVincenzo JP. Respiratory virus infections in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:962–968. doi: 10.1086/322628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee JH, Jang JH, Lee SH, Kim YJ, Yoo KH, Sung KW, Lee NY, Ki CS, Koo HH. Respiratory viral infections during the first 28 days after transplantation in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clinical Transplantation. 2012;26:736–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Choi JH, Choi EH, Kang HJ, Park KD, Park SS, Shin HY, Lee HJ, Ahn HS. Respiratory viral infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2013;28:36–41. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Srinivasan A, Gu ZM, Smith T, Morgenstern M, Sunkara A, Kang GL, Srivastava DK, Gaur AH, Leung W, Hayden RT. Prospective Detection of Respiratory Pathogens in Symptomatic Children With Cancer. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2013;32:E99–E104. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827bd619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Whimbey E, Champlin RE, Couch RB, Englund JA, Goodrich JM, Raad I, Przepiorka D, Lewis VA, Mirza N, Yousuf H, Tarrand JJ, Bodey GP. Community respiratory virus infections among hospitalized adult bone marrow transplant recipients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;22:778–782. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Williamson ECM, Millar MR, Steward CG, Cornish JM, Foot ABM, Oakhill A, Pamphilon DH, Reeves B, Caul EO, Warnock DW, Marks DI. Infections in adults undergoing unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation. British Journal of Haematology. 1999;104:560–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Roghmann M, Ball K, Erdman D, Lovchik J, Anderson LJ, Edelman R. Active surveillance for respiratory virus infections in adults who have undergone bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2003;32:1085–1088. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hassan IA, Chopra R, Swindell R, Mutton KJ. Respiratory viral infections after bone marrow/peripheral stem-cell transplantation: the Christie hospital experience. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2003;32:73–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Martino R, Porras RP, Rabella N, Williams JV, Ramila E, Margall N, Labeaga R, Crowe JE, Coll P, Sierra J. Prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and outcome of symptomatic upper and lower respiratory tract infections by respiratory viruses in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants for hematologic malignancies. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dignan F, Alvares C, Riley U, Ethell M, Cunningham D, Treleaven J, Ashley S, Bendig J, Morgan G, Potter M. Parainfluenza type 3 infection post stem cell transplant: high prevalence but low mortality. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2006;63:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Schiffer JT, Kirby K, Sandmaier B, Storb R, Corey L, Boeckh M. Timing and severity of community acquired respiratory virus infections after myeloablative versus non-myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2009;94:1101–1108. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.003186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wasserman M, Kulka RG, Loyter A. Degradation and localization of IgG injected into Friend erythroleukemic cells by fusion with erythrocyte ghosts. FEBS Letters. 1977;83:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ljungman P, Ward KN, Crooks BNA, Parker A, Martino R, Shaw PJ, Brinch L, Brune M, De La Camara R, Dekker A, Pauksen K, Russell N, Schwarer AP, Cordonnier C. Respiratory virus infections after stem cell transplantation: a prospective study from the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;28:479–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Crippa F, Holmberg L, Carter RA, Hooper H, Marr KA, Bensinger W, Chauncey T, Corey L, Boeckh M. Infectious complications after autologous CD34-selected peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood & Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8:281–289. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12064366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Machado CM, Boas LSV, Mendes AVA, Santos MFM, da Rocha IF, Sturaro D, Dulley FL, Pannuti CS. Low mortality rates related to respiratory virus infections after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2003;31:695–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Raboni SM, Nogueira MB, Tsuchiya LRV, Takahashi GA, Pereira LA, Pasquini R, Siqueira MM. Respiratory tract viral infections in bone marrow transplant patients. Transplantation. 2003;76:142–146. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000072012.26176.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Craft AW, Reid MM, Gardner PS. Virus infections in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1979;54:755–759. doi: 10.1136/adc.54.10.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mottonen M, Uhari M, Lanning M, Tuokko H. Prospective controlled survey of viral infections in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during chemotherapy. Cancer. 1995;75:1712–1717. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950401)75:7<1712::aid-cncr2820750724>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Martino R, Ramila E, Rabella N, Munoz JM, Peyret M, Portos JM, Laborda R, Sierra J. Respiratory virus infections in adults with hematologic malignancies: a prospective study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36:1–8. doi: 10.1086/344899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Park SY, Baek S, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim YS, Woo JH, Sung H, Kim MN, Kim DY, Lee JH, Lee KH, Kim SH. Efficacy of oral ribavirin in hematologic disease patients with paramyxovirus infection: Analytic strategy using propensity scores. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57:983–989. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01961-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chemaly RF, Ghosh S, Bodey GP, Rohatgi N, Safdar A, Keating MJ, Champlin RE, Aguilera EA, Tarrand JJ, Raad II. Respiratory viral infections in adults with hematologic malignancies and human stem cell transplantation recipients: a retrospective study at a major cancer center. Medicine. 2006;85:278–287. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000232560.22098.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Couch RB, Englund JA, Whimbey E. Respiratory viral infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised persons. American Journal of Medicine. 1997;102:2–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00003-X. discussion 25-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.