Abstract

Src, a non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase involved in many biological processes, can be activated through both redox-dependent and independent mechanisms. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) is a lipid peroxidation product that is increased in pathophysiological conditions associated with Src activation. This study examined how HNE activates human c-Src. In the canonical pathway Src activation is initiated by dephosphorylation of pTyr530 followed by conformational change that causes Src auto-phosphorylation at Tyr419 and its activation. HNE increased Src activation in both dose- and time-dependent manner, while it also increased Src phosphorylation at Tyr530 (pTyr530 Src), suggesting that HNE activated Src via a non-canonical mechanism. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor (539741), at concentrations that increased basal pTyr530 Src, also increased basal Src activity and significantly reduced HNE-mediated Src activation. The EGFR inhibitor, AG1478, and EGFR silencing, abrogated HNE-mediated EGFR activation and inhibited basal and HNE-induced Src activity. In addition, AG1478 also eliminated the increase of basal Src activation by a PTP1B inhibitor. Taken together these data suggest that HNE can activate Src partly through a non-canonical pathway involving activation of EGFR and inhibition of PTP1B.

Keywords: Src kinase, lipid peroxidation, signal transduction, redox signaling, protein tyrosine phosphatase, EGFR

1. Introduction

Src is the first discovered proto-oncogene that is a ubiquitously expressed non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase. It is involved in many fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and transformation [1] through mediating multiple cell signaling pathways [2]. Src activity is increased in more than 50% of tumors including colon [3], lung, pancreatic carcinoma [4], and prostate cancers [5], and its increased activity is a marker of poor clinic prognosis of tumors [6]. In addition, Src also participates in many other pathophysiological changes including inflammation [7] and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [8–12], a process implicated in wound healing and cancer metastasis [13–16].

In the canonical pathway, Src remains inactive under basal condition in vivo, due to the intramolecular interactions between its SH3 domain and proline-rich linker region and that between its SH2 domain and the phosphorylated Tyr530 (pTyr530) in the C-terminal negative regulatory region [17,18]. Upon stimulation, pTyr530 is dephosphorylated and the inhibitory intracellular interactions dissociate, allowing Src autophosphorylation at Tyr419, leading to its activation [19–22]. Therefore dephosphorylation of Tyr530 is the essential characteristic step in the canonical pathway of Src activation. C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) and Csk homologous kinase (Chk) phosphorylate Src at Tyr530, while protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) 1B, PTPα, PTPγ, and SHP1, have been shown to catalyze pTyr530 dephosphorylation [23].

c-Src is activated in response to many stimulants through the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and insulin-like growth factor-(IGF-) 1 receptor (IGF-1R), or through G-protein-coupled receptors that recognize cytokines [24]. Active RTKs phosphorylate tyrosine of Src and activate it directly after association with Src through SH2 domain [25]. RTKs can also interact with Src through its SH2 domain, disrupt its intracellular interactions, and lead to Src autophosphorylation and activation [26,27]. Non-tyrosine kinase receptors, on the other hand, may interact with Src through its SH3 domain and cause Src conformation change and activation [28].

Accumulating evidence suggests that Src can be activated through another alternative mechanism; i.e., a redox dependent mechanism. Src is activated by various oxidative stimuli including H2O2, peroxynitrite, acrolein, and cigarette smoke [29–33]. In fact, Src activation by many other stimuli including growth factors is also redox dependent [34–37]. Redox-dependent Src activation can occur without pTyr530 dephosphorylation [33,34,38] with early studies in this area suggesting that oxidative modification of redox sensitive cysteine (Cys) residues in Src may underlie the redox-dependent regulation of Src activity [39].

Oxidants and electrophiles usually mediate signal transduction by directly modifying moieties on signaling proteins. Signaling molecules containing redox sensitive cys such as PTPs, are the most likely potential targets of such redox modification [40–46]. PTPs share a similar catalytic site structure containing a reactive cys moiety [47,48] that is susceptible to oxidative modification [49]. Oxidation of this cys moiety inhibits PTP activity and thereby allows sustained or elevated phosphorylation of its target signaling molecules.

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) is a major α,β-unsaturated aldehyde product of lipid peroxidation [50]. It is found ubiquitously in mammalian tissues and fluids and is increased remarkably under oxidative stress [51,52]. HNE has been implicated in various oxidative stress-related cellular processes and diseases including neurodegenerative diseases [53], fibrotic diseases [54], and cancers [55]. At moderate concentration however, HNE is a potent signaling mediator and can modulate cell signaling by conjugating with redox reactive moieties, most notably cysteine, in signaling proteins [56,57] including PKC, RTKs [58], and PTPs [59,60].

There is a clear overlap between the pathophysiological conditions involving Src and HNE, i.e. both are implicated in cancer [2,24,55], inflammation [7,61], and fibrosis [54], etc., suggesting that HNE might contribute to Src activation under these pathologies. Previously we showed that Src was activated by electrophiles [33], but the molecular mechanism has not been elucidated. Here using HNE as a model electrophile, we further explore the signaling pathways involved in electrophile-mediated Src activation.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies to Src, phosphorylated Src, and phospho-EGFR (Tyr845), were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). EGFR siRNA, M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent, and RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer were from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). AG1478 was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). PTP1B inhibitor (539741, 3-(3,5–dibromo-4-hydroxy-benzoyl) – 2-ethyl-benzofuran-6-sulfonicacid – (4 – (thiazol-2-yl-sulfamyl)-phenyl)-amide)) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Dallas, TX). HNE was from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). All chemicals used were at least analytical grade.

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

A human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line (H358) was used. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fatal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were treated when at about 85% confluence.

2.3. Western Analysis

Briefly, cell lysate was extracted with RIPA buffer and 30 μg protein was electrophoresed on a 4–20% Tris-glycine acrylamide gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody in 5% BSA dissolved in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). After being washed with 1XTBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TTBS), membranes were incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. After TTBS washing, membranes were treated with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent mixture (ECL Plus; Thermal Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 5 min and then imaged and analyzed using the biospectrum imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Wilcoxon rank-Sign test was used for statistical analysis of Western densitometry data. Statistical significance was accepted when p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. HNE activates Src in a dose- and time-dependent manner

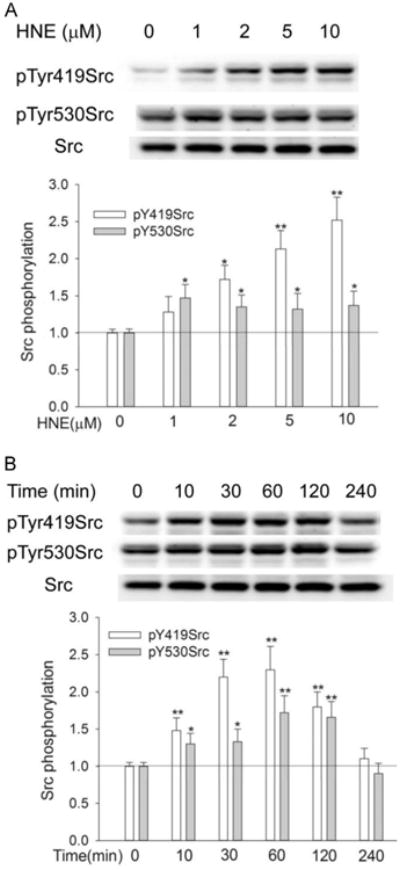

To examine Src activation by HNE, human H358 cells were exposed to various doses of HNE and Src phosphorylation at Tyr419, a marker of Src activation, was determined with Western Blotting. Similarly Tyr530 phosphorylation was also determined with the same samples. At concentration as low as 1 μM, HNE increased pTyr419 in c-Src by 30% after 1 h exposure. Src activation was increased by 70%, 110%, and 150% with a HNE concentration of 2, 5 and 10 μM, respectively (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

HNE activated Src in dose- and time-dependent manner. (A) HNE dose-dependently increased Src phosphorylation at Tyr419 and Tyr530; (B) Src phosphorylation was increased by HNE in a time-dependent manner. Cells were exposed to different HNE concentrations for 1 h (A) or to 10 μM HNE for indicated time (B), and pTyr419Src and pTyr530Src were determined by Western Blotting. *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01, compared with control, N= 3.

Time-dependent Src activation was determined with 10 μM HNE. As shown in Figure1B, pSrc419Src began to increase at 10 min following HNE exposure and reached maximum at 1 h. Src activation remained as long as 2 h and was back to normal after 4 h of HNE exposure.

3.2. Src activation by HNE is independent of pTyr530 dephosphorylation

As mentioned, Src activity can be regulated through either pTyr530 dephosphorylation dependent (classic pathway) or independent pathway. To explore whether pTyr530 depho-sphorylation is involved in Src activation by HNE, we first investigated the phosphorylation status of Tyr530 upon HNE exposure. As shown in Fig. 1, Src activation by HNE was accompanied with a simultaneous increase of pTyr530Src, and the changing pattern of both pTyr419Src and pTyr530Src, either with time or with variation of HNE concentrations, was similar. This suggests that dephosphorylation of pTyr530 might not be necessary for HNE-mediated Src activation.

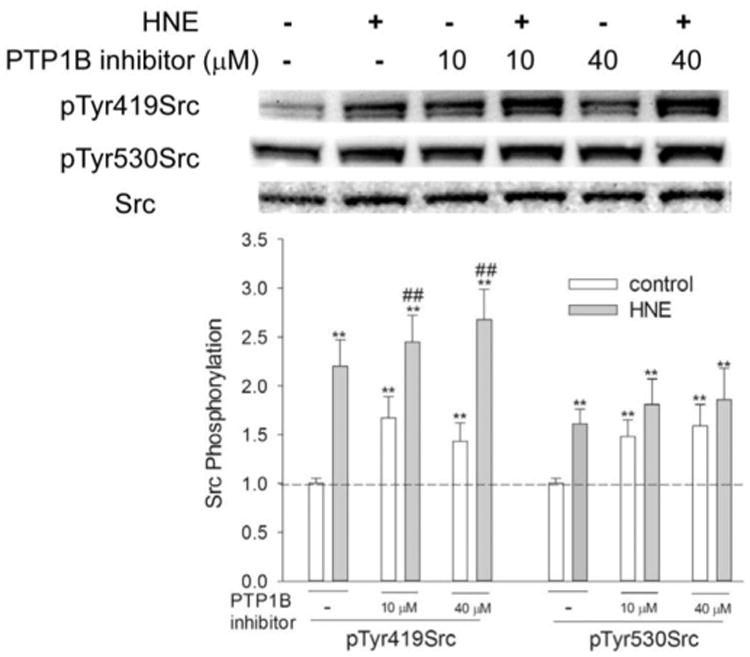

PTP1B is reportedly involved in the dephosphorylation of both c-Src pTyr530 and RTKs [23]. To further confirm whether or not dephosphorylation of pTyr530 is required for HNE-mediated Src activation, Src phosphorylation at Tyr419 and Tyr530 was determined in the presence of the PTP1B inhibitor, 539741. As shown in Fig. 2, 539741 increased the phosphorylation of Tyr530, indicating that PTP1B is involved in the dephosphorylation of pTyr530Src. Meanwhile, 539741 also increased pTyr419Src, meaning that PTP1B is also involved in the regulation of Src phosphorylation at Tyr419, possibly through either acting on pTyr419Src directly or on an upstream signaling kinase that mediates Src activation. Generally, PTP1B inhibition, which increased pTyr530Src, decreased, but this did not abrogate Src activation by HNE. Taken together, these data indicate that dephosphorylation of pTyr530 is not a prerequisite and that PTP1B inhibition plays an important role in Src activation by HNE.

Fig. 2.

Effect of 539741 on Src phosphorylation by HNE. Cells were pretreated with different concentrations of 539741for 1 h before being exposed to 10 μM HNE, Src phosphorylation at both Tyr530 and Tyr419 was then determined by Western Blotting. *, P<0.05, **, p<0.01, compared with vehicle control; #, p<0.05, ##, P<0.01, compared with control of same concentration of PTP1B inhibitor, N=3.

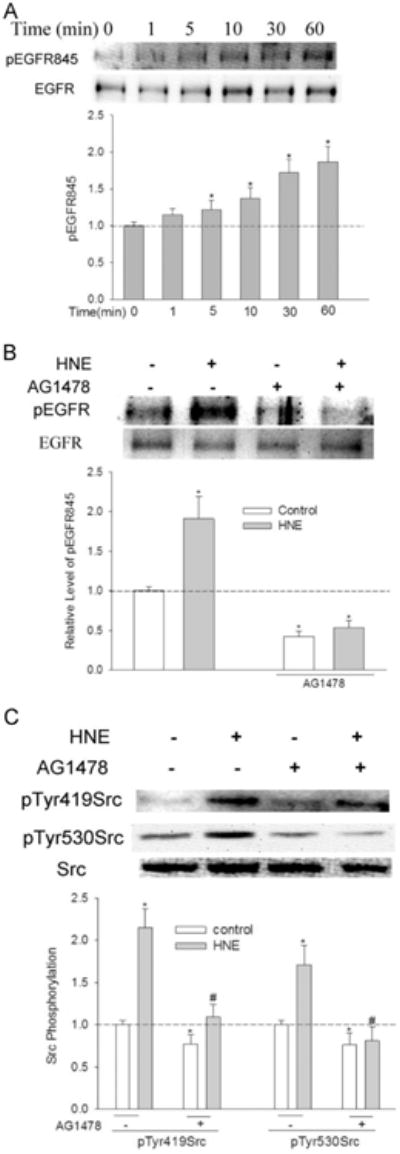

3.3. EGFR inhibitor and EGFR siRNA silencing reduced Src activation by HNE

EGFR is an upstream signaling molecule that interacts with Src [62,63]. As EGFR was activated by HNE (Fig. 3A), we wondered if HNE-mediated Src activation was through EGFR. To test this hypothesis, cells were pretreated with the EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 before being exposed to HNE. AG1478 (10 μM) pretreatment abrogated HNE-stimulated activation of EGFR (Fig. 3B, shown as EGFR phosphorylation at Tyr845), meanwhile it significantly inhibited the basal and HNE-mediated Src activation (Fig. 3C), indicating that EGFR is involved in both basal and HNE-induced Src activation. HNE-mediated increase of pTyr530Src was also reduced significantly by AG1478, suggesting a possible interaction between EGFR activation and Src phosphorylation at Tyr530. However, even in the presence of AG1478, Src was still activated by HNE by about 50% (compared with 120% without AG1478).

Fig. 3.

EGFR is involved in HNE-mediated Src activation. (A) HNE caused EGFR Tyr845 phosphorylation; cells were treated with 10 μM HNE for indicated time and the phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr845 was determined with Western Blotting. *, P<0.01 compared with starting time, N=3. (B) AG1478 abrogated HNE-mediated EGFR activation. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM AG1478 for 30 min before exposure to HNE for 1 h, and pTyr845 EGFR was determined. *, P<0.01 compared with vehicle control, N=3. (C) EGFR inhibitor AG1478 diminished Src activation by HNE. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM AG1478 for 30 min before being exposed to HNE for 1 h, and pTyr419Src was determined with Western Blotting. *, P<0.01 compared with vehicle control; #, P<0.01 compared with HNE, N=3.

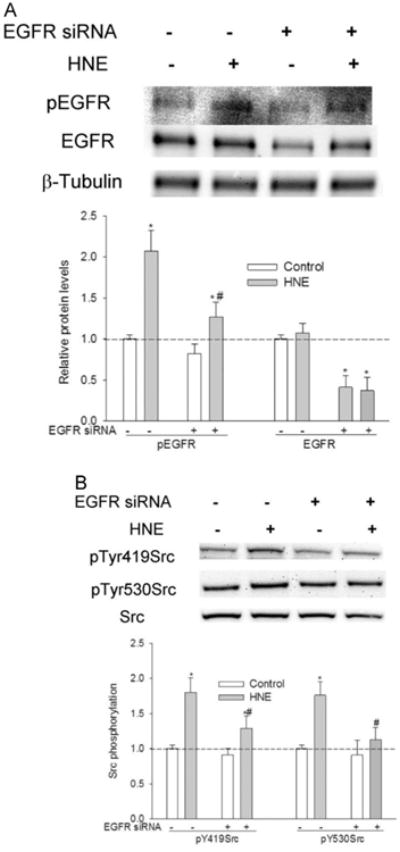

To further confirm the involvement of EGFR in HNE-mediated Src activation, EGFR expression was silenced with siRNA before being exposed to HNE. EGFR siRNA caused about 65% decrease in EGFR protein expression and a corresponding decrease in EGFR activation by HNE (Fig. 4A). EGFR silencing led to a significant decrease in Src activation by HNE (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of EGFR silencing on HNE-mediated Src activation. Cells were transiently transfected with EGFR siRNA (50 nM) for 72 h before being treated with HNE. (A) EGFR silencing with siRNA. *, P<0.01 compared with vehicle control, #, P<0.01 compared with HNE, N=3. (B) EGFR silencing reduced Src activation by HNE. *, P<0.01 compared with vehicle control, #, P<0.01 compared with HNE, N=3.

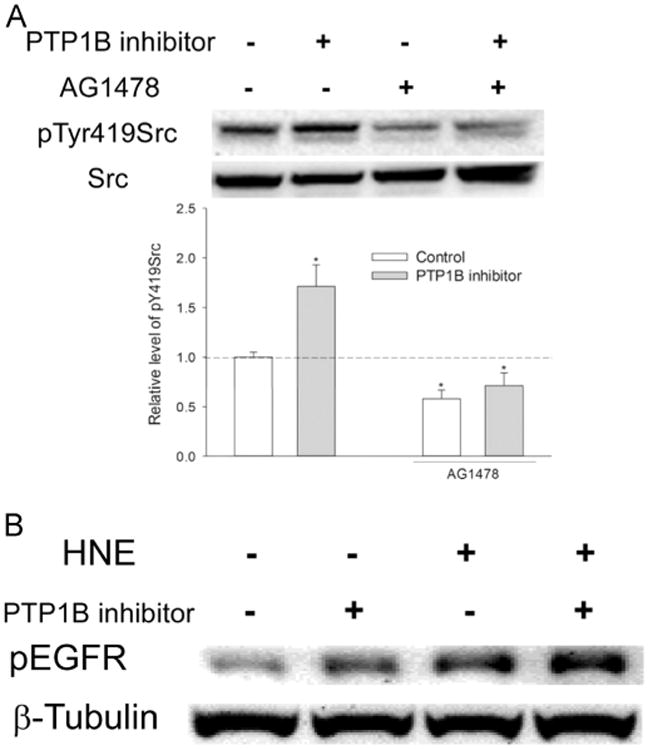

3.4. EGFR inhibitor abrogated PTP1B inhibitor-induced Src activation

As a receptor tyrosine kinase, activity of EGFR is regulated by PTPs. we hypothesized that the effect of 539741 on Src activity (Fig. 2B) was through its inhibition of EGFR dephosphorylation by PTP1B. To test it, cells were pretreated with EGFR inhibitor AG1478 before being treated with 539741. As shown in Fig. 5A, the activation of Src (shown as pTyr419Src) by 539741 was abrogated in the presence of AG1478, revealing that PTP1B negatively regulates Src through EGFR dephosphorylation that eliminates the ability of EGFR to phosphorylate Src. To further confirm it, effect of 539741 on EGFR activation was examined. Treatment with 539741 increased phosphorylation of EGFR, which was further enhanced by HNE exposure (Fig. 5B). In all these data suggest that PTP1B-regulated EGFR activation is involved in HNE-mediated Src activation.

Fig. 5.

EGFR is a PTP1B target. (A) EGFR was involved in PTP1B-mediated Src activation. Cells were pretreated with/without 10 μM AG1478 for 30 min before being exposed to 20 μM 539741 for 30 min, and pTyr419Src and total Src was determined with Western Blotting. *, P<0.01 compared with vehicle control, N=3. (B) PTP1B regulated EGFR phosphorylation at Tyr845 by HNE. Cells were pretreated with/without 20 μM 539741 for 30 min before being exposed to HNE for 1 h, and pEGFR845 was determined with Western blotting.

4. Discussion

Src mediates multiple cell signaling pathways [64] and is involved in cancers, inflammation, immune response, and many other pathophysiological processes [65–68]. Src activation in response to oxidative stress has been well established [68–71], and the underlying mechanism involves oxidative modification of cysteine residuals in Src. The current study suggests that HNE, a major lipid peroxidation product and signaling mediator, likely contributes to Src activation under oxidative stress. In line with current finding, data from others showed that activation of Src was involved in some bio-effects caused by HNE [72,73]. In contrast, Liu et al. reported that Src was inhibited by HNE [74]. It was possible that this apparently contradictory effect of HNE on Src regulation was due to HNE concentration, as a dose that causes apoptosis was used in Liu's study while a mild dose that did not cause visible morphological changes of cells was used in the current study. The dual effect of HNE on protein activity has been observed in other signaling proteins such as RTKs when HNE is applied at higher concentrations and/or for longer incubation time. Under these conditions, HNE causes an inhibitory instead of activation effect on signaling molecules [75]. Another possible explanation is that PTPs dephosphorylating pTyr530Src were highly expressed in Liu's model, and HNE exposure, which inhibits these PTPs, could result in relatively higher pTyr530Src and less Src activity. Nonetheless, the evidence that various oxidants and lipid peroxidation products can activate Src suggests that Src regulation under oxidative stress is a combined effect from multiple oxidants and electrophiles. It remains a challenge however, to determine the exact relative contribution of single oxidant and/or electrophile to Src activation under oxidative stress.

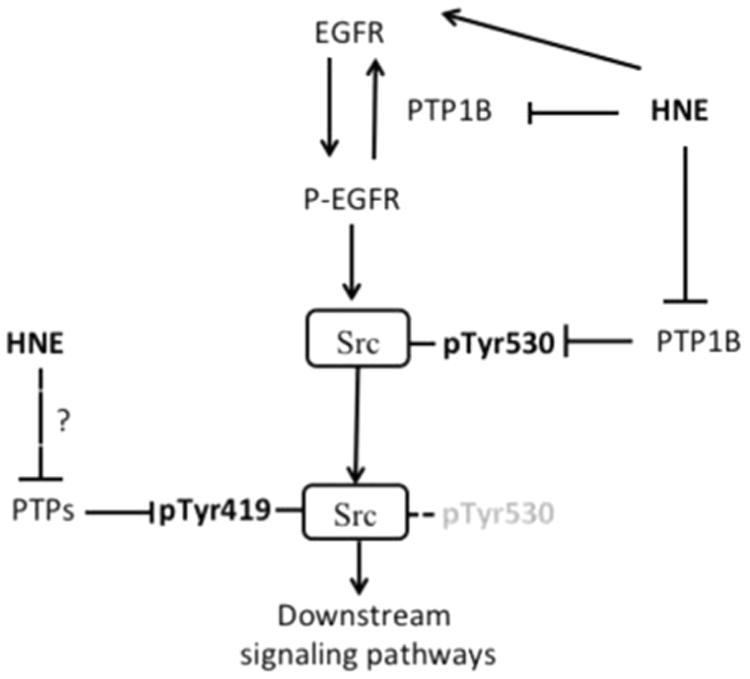

The current study shows that dephosphorylation of pTyr530 is not required in HNE-mediated Src activation, as Src activation occurred concurrently with an increase rather than decrease of pTyr530Src (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). In the canonical pathway, pTyr530 dephosphorylation leads to the disassembly of inhibitory intramolecular associations in Src that results in Src autophosphorylation. Accumulating evidence however shows that oxidant-induced Src activation can bypass pTyr530 dephosphorylation and follow other mechanisms [70,76]. Here we demonstrated that EGFR activation was an upstream event in Src activation by HNE (Figs. 3 and 4). To support this, Dittmann et al. reported that radiation-induced Src activation was through the activation of EGFR by lipid peroxidation product HNE [73]. Although the underlying mechanism was undetermined, an activation of Src through EGFR has been well documented [62,77]. HNE is a stimulator of EGFR [57,75] and its activation of Src was therefore anticipated. HNE may activate EGFR through forming HNE-EGFR conjugates [58,75,78], or through inhibiting PTPs that dephosphorylate activated EGFR, or through both mechanisms. HNE is a potent inhibitor of PTPs, including SHP-1[59] and PTEN [60] while EGFR is a substrate of PTP1B [79] (Fig. 5). Data from this study demonstrate that PTP1B plays an important role in HNE-mediated EGFR activation and Src activation.

The data here suggest that EGFR was also involved in the HNE-mediated increase in pTyr530Src (Figs. 3 and 4). Tyr530 phosphorylation is regulated by both tyrosine kinases such as CSK and PTPs. EGF stimulation could induce tyrosine phosphorylation of CSK-binding protein (CBP), and thus increase CBP-CSK association [80], resulting in increased CSK activity and Tyr530 phosphorylation of Src.

It should be noted however, that besides EGFR/PTP1B, other signaling pathways might also be involved in HNE-mediated Src activation, as the inhibitory effect of EGFR inhibitor or its silencing on HNE-mediated Src activation is not complete. One possible pathway is via inhibition of PTPs that directly dephosphorylate pTyr419Src. Up to now less is known about these PTPs and how they could be regulated by oxidant/electrophiles. Another possible pathway may involve the modification of cysteine residues in Src. Several studies have shown that direct oxidation/alkylation of these cysteinyl residues can change Src confirmation and lead to its activation [38,39,81,82]. Indeed mutation of these cysteine moieties abrogated HNE-mediated Src activation (data not shown).

In summary, current study provides evidence that HNE, a major aldehyde lipid peroxidation product, could activate Src mainly through PTP1B/EGFR pathway (Fig. 6). However, HNE might also activate Src via acting on PTPs involved in the dephosphorylation of pTyr419Src and/or modify the cysteine moieties in Src and cause Src activaiton directly.

Fig. 6.

Regulatory mechanism of Src activation by HNE. HNE could activate EGFR directly through forming conjugate or indirectly through inhibiting PTP1B, which dephosphorylates/inhibits pEGFR845. Active pEGFR then activates Src. PTP1B is also involved in dephosphorylation of pTyr530Src. Whether HNE inhibits PTPs involved in dephosphorylation of pTyr419Src is unknown.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R21-ES020942.

References

- 1.Parsons SJ, Parsons JT. Src family kinases, key regulators of signal transduction. Oncogene. 2004;23:7906–7909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarino M. Src signaling in cancer invasion. Journal of cellular physiology. 2010;223:14–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talamonti MS, Roh MS, Curley SA, Gallick GE. Increase in activity and level of pp60c-src in progressive stages of human colorectal cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;91:53–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutz MP, Esser IB, Flossmann-Kast BB, Vogelmann R, Luhrs H, Friess H, Buchler MW, Adler G. Overexpression and activation of the tyrosine kinase Src in human pancreatic carcinoma. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;243:503–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2003;22:337–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aligayer H, Boyd DD, Heiss MM, Abdalla EK, Curley SA, Gallick GE. Activation of Src kinase in primary colorectal carcinoma: an indicator of poor clinical prognosis. Cancer. 2002;94:344–351. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byeon SE, Yi YS, Oh J, Yoo BC, Hong S, Cho JY. The role of Src kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators of inflammation. 2012;2012:512926. doi: 10.1155/2012/512926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu KP, Yin J, Yu FS. SRC-family tyrosine kinases in wound- and ligand-in-duced epidermal growth factor receptor activation in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2832–2839. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicchini C, Laudadio I, Citarella F, Corazzari M, Steindler C, Conigliaro A, Fantoni A, Amicone L, Tripodi M. E.M.T. TGFbeta-induced, requires focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Experimental cell research. 2008;314:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulianich L, Garbi C, Treglia AS, Punzi D, Miele C, Raciti GA, Beguinot F, Consiglio E, Di Jeso B. ER stress is associated with dedifferentiation and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like phenotype in PC Cl3 thyroid cells. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:477–486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang SZ, Zhang LD, Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Zhang YJ, Li HL, Li XW, Dong JH. HBx protein induces EMT through c-Src activation in SMMC-7721 hepatoma cell line. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;382:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Orozco R, Navarro-Tito N, Soto-Guzman A, Castro-Sanchez L, Perez Salazar E. Arachidonic acid promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal-like transition in mammary epithelial cells MCF10A. European journal of cell biology. 2010;89:476–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yauch RL, Januario T, Eberhard DA, Cavet G, Zhu W, Fu L, Pham TQ, Soriano R, Stinson J, Seshagiri S, Modrusan Z, Lin CY, O'Neill V, Amler LC. Epithelial versus mesenchymal phenotype determines in vitro sensitivity and predicts clinical activity of erlotinib in lung cancer patients. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:8686–8698. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis BC, Borok Z. TGF-beta-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2007;293:L525–L534. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00163.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soltermann A, Tischler V, Arbogast S, Braun J, Probst-Hensch N, Weder W, Moch H, Kristiansen G. Prognostic significance of epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial transition protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14:7430–7437. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gharaee-Kermani M, Hu B, Phan SH, Gyetko MR. Recent advances in molecular targets and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: focus on TGFbeta signaling and the myofibroblast. Current medicinal chemistry. 2009;16:1400–1417. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada M, Nakagawa H. A protein tyrosine kinase involved in regulation of pp60c-src function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1989;264:20886–20893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su J, Muranjan M, Sap J. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha activates Src-family kinases and controls integrin-mediated responses in fibro-blasts. Current biology: CB. 1999;9:505–511. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannoni E, Taddei ML, Chiarugi P. Src redox regulation: again in the front line. Free radical biology & medicine. 2010;49:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Esselman WJ, Cole PA. Substrate conformational restriction and CD45-catalyzed dephosphorylation of tail tyrosine-phosphorylated Src protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:40428–40433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SE, Wu FY, Shin I, Qu S, Arteaga CL. Transforming growth factorβ (TGF-β)-Smad target gene protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type kappa is required for TGF-β function. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:4703–4715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4703-4715.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen B, Johnson FM. Regulation of SRC family kinases in human cancers. Journal of signal transduction. 2011;2011:865819. doi: 10.1155/2011/865819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer cell. 2004;6:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sierke SL, Koland JG. SH2 domain proteins as high-affinity receptor tyrosine kinase substrates. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10102–10108. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso G, Koegl M, Mazurenko N, Courtneidge SA. Sequence requirements for binding of Src family tyrosine kinases to activated growth factor receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:9840–9848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas JW, Ellis B, Boerner RJ, Knight WB, White GC, 2nd, Schaller MD. SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:577–583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luttrell LM, Miller WE. Arrestins as regulators of kinases and phosphatases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;118:115–147. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394440-5.00005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallozzi C, Di Stasi AM, Minetti M. Activation of src tyrosine kinases by peroxynitrite. FEBS letters. 1999;456:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00945-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhuang S, Schnellmann RG. H2O2-induced transactivation of EGF receptor requires Src and mediates ERK1/2, but not Akt, activation in renal cells. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2004;286:F858–F865. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00282.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehdi MZ, Pandey NR, Pandey SK, Srivastava AK. H2O2-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and PKB requires tyrosine kinase activity of insulin receptor and c-Src. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2005;7:1014–1020. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krasnowska EK, Pittaluga E, Brunati AM, Brunelli R, Costa G, De Spirito M, Serafino A, Ursini F, Parasassi T. N-acetyl-l-cysteine fosters inactivation and transfer to endolysosomes of c-Src. Free radical biology & medicine. 2008;45:1566–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, Liu H, Borok Z, Davies KJ, Ursini F, Forman HJ. Cigarette smoke extract stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through Src activation. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;52:1437–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannoni E, Buricchi F, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Intracellular reactive oxygen species activate Src tyrosine kinase during cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:6391–6403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6391-6403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng D, Shi X, Jiang BH, Fang J. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) induces epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and cell proliferation through reactive oxygen species. Free radical biology & medicine. 2007;42:1651–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Arnott JA, Rehman S, Delong WG, Jr, Sanjay A, Safadi FF, Popoff SN. Src is a major signaling component for CTGF induction by TGF-beta1 in osteoblasts. Journal of cellular physiology. 2010;224:691–701. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan SR, Berton G. Regulation of Src family tyrosine kinase activities in adherent human neutrophils. Evidence that reactive oxygen intermediates produced by adherent neutrophils increase the activity of the p58c-fgr and p53/56lyn tyrosine kinases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:23464–23471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, Davies KJ, Forman HJ. TGFbeta1 rapidly activates Src through a non-canonical redox signaling mechanism. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2015;568:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oo ML, Senga T, Thant AA, Amin AR, Huang P, Mon NN, Hamaguchi M. Cysteine residues in the C-terminal lobe of Src: their role in the suppression of the Src kinase. Oncogene. 2003;22:1411–1417. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett W, DeGnore JP, Konig S, Fales HM, Keng YF, Zhang ZY, Yim MB, Chock PB. Regulation of PTP1B via glutathionylation of the active site cysteine 215. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6699–6705. doi: 10.1021/bi990240v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiarugi P. The redox regulation of LMW-PTP during cell proliferation or growth inhibition. IUBMB life. 2001;52:55–59. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denu J, Tanner KG. Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5633–5642. doi: 10.1021/bi973035t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krejsa CM, Nadler SG, Esselstyn JM, Kavanagh TJ, Ledbetter JA, Schieven GL. Role of oxidative stress in the action of vanadium phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. Redox independent activation of NF-kB. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:11541–11549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee S, Kwon KS, Kim SR, Rhee SG. Reversible inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in A431 cells stimulated with epidermal growth factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:15366–15372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S, Whorton AR. Regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in intact cells by S-nitrosothiols. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2003;410:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatases: small, but smart. Cell and Molecular Life Sciences. 2002;59:941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barford D. Protein phosphatases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:728–734. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neel B, Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;2:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forman HJ, Maiorino M, Ursini F. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2010;49:835–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poli G, Schaur RJ, Siems WG, Leonarduzzi G. 4-hydroxynonenal: a membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Medicinal research reviews. 2008;28:569–631. doi: 10.1002/med.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uchida K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poli G, Biasi F, Leonarduzzi G. 4-Hydroxynonenal-protein adducts: A reliable biomarker of lipid oxidation in liver diseases. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2008;29:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Floyd RA, Hensley K. Oxidative stress in brain aging. Implications for therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of aging. 2002;23:795–807. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leonarduzzi G, Scavazza A, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E, Camandola S, Vogel S, Dargel R, Poli G. The lipid peroxidation end product 4-hydroxy-2,3-nonenal up-regulates transforming growth factor beta1 expression in the macrophage lineage: a link between oxidative injury and fibrosclerosis. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1997;11:851–857. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pizzimenti S, Toaldo C, Pettazzoni P, Dianzani MU, Barrera G. The “two-faced” effects of reactive oxygen species and the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in the hallmarks of cancer. Cancers. 2010;2:338–363. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dwivedi S, Sharma A, Patrick B, Sharma R, Awasthi YC. Role of 4-hydroxynonenal and its metabolites in signaling. Redox report: communications in free radical research. 2007;12:4–10. doi: 10.1179/135100007X162211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forman HJ, Fukuto JM, Miller T, Zhang H, Rinna A, Levy S. The chemistry of cell signaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and 4-hydroxynonenal. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2008;477:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suc I, Meilhac O, Lajoie-Mazenc I, Vandaele J, Jurgens G, Salvayre R, Negre-Salvayre A. Activation of EGF receptor by oxidized LDL. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1998;12:665–671. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.9.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rinna A, Forman HJ. SHP-1 inhibition by 4-hydroxynonenal activates Jun N-terminal kinase and glutamate cysteine ligase. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2008;39:97–104. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0371OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shearn CT, Smathers RL, Backos DS, Reigan P, Orlicky DJ, Petersen DR. Increased carbonylation of the lipid phosphatase PTEN contributes to Akt2 activation in a murine model of early alcohol-induced steatosis. Free radical biology & medicine. 2013;65:680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu ST, Pham H, Pandol SJ, Ptasznik A. Src as the link between inflammation and cancer. Frontiers in physiology. 2013;4:416. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leu TH, Maa MC. Functional implication of the interaction between EGF receptor and c-Src. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2003;8:s28–38. doi: 10.2741/980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egloff AM, Grandis JR. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor and SRC pathways in head and neck cancer. Seminars in oncology. 2008;35:286–297. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wheeler DL, Iida M, Dunn EF. The role of Src in solid tumors. The oncologist. 2009;14:667–678. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reinehr R, Sommerfeld A, Haussinger D. The Src family kinases: distinct functions of c-Src, Yes, and Fyn in the liver. Biomolecular concepts. 2013;4:129–142. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2012-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacKay CE, Knock GA. Control of vascular smooth muscle function by Src family kinases and reactive oxygen species in health and disease. The Journal of physiology. 2014 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karki R, Zhang Y, Igwe OJ. Activation of c-Src: a hub for exogenous pro-oxidant-mediated activation of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;71:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devary Y, Gottlieb RA, Smeal T, Karin M. The mammalian ultraviolet response is triggered by activation of Src tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1992;71:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gonzalez-Rubio M, Voit S, Rodriguez-Puyol D, Weber M, Marx M. Oxidative stress induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGF alpha-and beta-receptors and pp60c-src in mesangial cells. Kidney international. 1996;50:164–173. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pu M, Akhand AA, Kato M, Hamaguchi M, Koike T, Iwata H, Sabe H, Suzuki H, Nakashima I. Evidence of a novel redox-linked activation mechanism for the Src kinase which is independent of tyrosine 527-mediated regulation. Oncogene. 1996;13:2615–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung S, Vu S, Filosto S, Goldkorn T. Src Regulates Cigarette Smoke-induced Ceramide Generation via nSMase2 in the Airway Epithelium. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2014 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0122OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumagai T, Matsukawa N, Kaneko Y, Kusumi Y, Mitsumata M, Uchida K. A lipid peroxidation-derived inflammatory mediator: identification of 4-hydro-xy-2-nonenal as a potential inducer of cyclooxygenase-2 in macrophages. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:48389–48396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dittmann K, Mayer C, Kehlbach R, Rothmund MC, Peter Rodemann H. Radiation-induced lipid peroxidation activates src kinase and triggers nuclear EGFR transport. Radiotherapy and oncology: journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2009;92:379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu W, Akhand AA, Takeda K, Kawamoto Y, Itoigawa M, Kato M, Suzuki H, Ishikawa N, Nakashima I. Protein phosphatase 2A-linked and -unlinked caspase-dependent pathways for downregulation of Akt kinase triggered by 4-hydroxynonenal. Cell death and differentiation. 2003;10:772–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Negre-Salvayre A, Vieira O, Escargueil-Blanc I, Salvayre R. Oxidized LDL and 4-hydroxynonenal modulate tyrosine kinase receptor activity. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2003;24:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akhand AA, Pu M, Senga T, Kato M, Suzuki H, Miyata T, Hamaguchi M, Nakashima I. Nitric oxide controls src kinase activity through a sulfhydryl group modification-mediated Tyr-527-independent and Tyr-416-linked mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:25821–25826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Belsches AP, Haskell MD, Parsons SJ. Role of c-Src tyrosine kinase in EGF-induced mitogenesis. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 1997;2:d501–d518. doi: 10.2741/a208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larroque-Cardoso P, Mucher E, Grazide MH, Josse G, Schmitt AM, Nadal-Wolbold F, Zarkovic K, Salvayre R, Negre-Salvayre A. 4-Hydroxynonenal impairs transforming growth factor-beta1-induced elastin synthesis via epidermal growth factor receptor activation in human and murine fibroblasts. Free radical biology & medicine. 2014;71:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haj FG, Markova B, Klaman LD, Bohmer FD, Neel BG. Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:739–744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang LQ, Feng X, Zhou W, Knyazev PG, Ullrich A, Chen Z. Csk-binding protein (Cbp) negatively regulates epidermal growth factor-induced cell transformation by controlling Src activation. Oncogene. 2006;25:5495–5506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Senga T, Miyazaki K, Machida K, Iwata H, Matsuda S, Nakashima I, Hamaguchi M. Clustered cysteine residues in the kinase domain of v-Src: critical role for protein stability, cell transformation and sensitivity to herbimycin A. Oncogene. 2000;19:273–279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kemble DJ, Sun G. Direct and specific inactivation of protein tyrosine kinases in the Src and FGFR families by reversible cysteine oxidation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5070–5075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806117106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]