Abstract

Dominant health care professional discourses on cancer take for granted high levels of individual responsibility in cancer prevention, especially in expectations about preventive screening. At the same time, adhering to screening guidelines can be difficult for lower-income and under-insured individuals. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prime example. Since the advent of CRC screening, disparities in CRC mortality have widened along lines of income, insurance, and race in the United States. We used a community-engaged research method, Photovoice, to examine how people from medically-underserved areas experienced and gave meaning to CRC screening. In our analysis, we first discuss ways in which participants recounted screening as a struggle. Second, we highlight a category that participants suggested was key to successful screening: social connections. Finally, we identify screening as an emotionally-laden process that is underpinned by feelings of uncertainty, guilt, fear, and relief. We discuss the importance of these findings to research and practice.

Keywords: adherence, compliance, cancer, screening and prevention, health care disparities, aging, older people, health, lived experience, prevention, illness and disease

During the past 35 years, advances in screening and treatment technologies have inspired optimism about the prevention and treatability of cancer and, in many parts of the United States, cancer mortality has decreased. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prime example. CRC screening allows for the identification and removal of precancerous polyps, contributing to declines in incidence (Edwards et al., 2014). Screening and subsequent early detection also increase survivability of CRC; the five-year survival rate for CRC is estimated at 90 percent when detected at an early stage (American Cancer Society, 2014). Such encouraging preventive and treatment outcomes have caused practitioners and researchers to give considerable weight to screening as a way to reduce CRC-related sickness and death.

Beneath the “success story” of CRC screening is a less encouraging account. Since the advent of preventive CRC screening, disparities in CRC mortality have widened along lines of race, ethnicity, insurance, income, and formal education (Albano et al., 2007). These disparities are due to a range of factors, but are partially attributed to differences in screening rates, which have resulted in the later detection of CRC. For example, in the United States, 67 percent of insured adults have been screened for CRC compared to 35 percent of uninsured adults and, in general, Whites have higher screening rates than other racial or ethnic groups (Steel et al., 2013). The low rate of screening among particular groups raises questions about the barriers to screening uptake and completion. Research focused on understanding CRC screening disparities has offered a range of reasons why people may not be screened, including the expense of screening, inadequate insurance coverage and reimbursement, substandard care, lack of recommendation by a provider, insufficient knowledge, medical mistrust, fear, embarrassment, and “fatalistic” attitudes (Bass et al., 2011; Harper et al., 2013; James et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2010; McQueen et al., 2008; Wardle et al., 2004). While this research has advanced understandings of CRC disparities, there remain significant gaps that need to be addressed to more fully comprehend and appropriately address CRC disparities. First, the attention to discrete barriers, and particularly to defining and quantitating cognitions and emotions, often decontextualizes cancer screening decisions, which always occur against the backdrop of political, economic, cultural, and familial processes as well as individual life experiences (Drew & Schoenberg, 2011). Second, focusing only on the people who do not get screened leaves unexamined the “success” cases, the persons who, according to medical guidelines, are up-to-date on screening. We suggest that attending to the in-depth experience of screening offers needed insight into CRC screening disparities, and provides attention to the ways in which people accomplish screening, achieve health care, and adhere to medical advice under significant resource constraint.

Our research focuses on one over-arching question: How do people from medically underserved areas experience and give meaning to the process of CRC screening? This question is underpinned by two separate but complementary theoretical and methodological approaches, which we use to conceptualize the relationship between macro-level policy shifts and on-the-ground experience and meaning making. First, in conceptualizing the broader context of cancer screening, we find helpful the work of social scientists who use a political economy framework to examine the effects on health and health care under neoliberalism. Neoliberalism, for the purposes of this article, refers to a mode of governance based on increased privatization, scaling back of public programs and aid to the poor, and the shifting of economic and social responsibilities away from the state and onto individuals and families (see Harvey 2005). It has been the dominant mode of governance shaping political, legal, social, and economic institutions in the United States since the early 1980s. The neoliberal shift became normalized in the United States in the mid-1990s at the same time as the welfare reform act, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, was passed (Ong, 2006).

A hallmark of the neoliberal context is that much of the labor for health has shifted away from health care providers and institutions and onto the individual, who is expected to purchase health insurance, engage in healthy lifestyle changes, and seek out care (Horton et al., 2014). Furthermore, health services have moved toward a more commodified and consumer-driven model. This is, in part, also a response to critiques of the health care system as paternalistic. The shift away from top-down medical decision making to a model that is more inclusive of patient choice has been seen as a positive change because it gives patients more control over their health care. We do not advocate a return to a paternalistic model of health care, but we do wish to recognize that, with the scaling back of institutional supports to the poor, the resources that people need to make informed choices are often lacking or difficult to access. In effect, the neoliberal context makes it challenging for some individuals to make health care decisions, and this aspect of health care further accentuates and reproduces disparities.

Inspired by Foucault’s work on neoliberal governmentality, scholars have used the term “responsibilization” to describe neoliberal governance models in which individuals are expected to be self-reliant, self-regulating, and forward-oriented (Clarke, 2005; Lemke, 2001; Merry, 2009; Rose, 1999). Current discourses and practices pertaining to cancer prevention and control are connected to wider trends in responsibilization. Dominant health care professional discourses on cancer take for granted high levels of individual responsibility and self-regulation in cancer prevention, through expectations about food choice, exercise, and smoking, and also screenings and symptom monitoring. As other scholars have shown, non-attendance in screening programs or non-adherence to guidelines is perceived as “abnormal” or “irrational,” and adherence is viewed as an ethical value (Bush, 2000; Drew & Schoenberg, 2011; Griffiths et al., 2010). The judgments about what people ought to do, which are implicit in these discourses, can become internalized. They affect people’s practices and behaviors and their perceptions of themselves. When cancer is diagnosed late, such judgments can produce feelings of guilt and reduce an individual’s successes or failures with cancer treatment to their own individual volitions (Griffiths et al., 2006; McMullin & Weiner, 2008).

The techniques used to screen for CRC offer an important area for studying how responsibilization affects, and is experienced by, people who are poor and medically under-served. CRC screening differs in important ways from other preventive screening tests. While the United States Preventive Services Task Force (2008) identifies three options for screening—colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and fecal occult blood test—the most commonly prescribed and utilized screening method in St. Louis (and most areas of the United States) is colonoscopy (Steel et al., 2013). Colonoscopy is unique among routine screening technologies: it is expensive, time-consuming, and invasive. The test requires fasting, a special preparation (“prep”) to clean out the colon, and an under-sedation procedure performed by a specialist. From preparation to post-procedure, the process lasts two days, making it both expensive and labor intensive. However, it is also a screening test recommended only once every 10 year, unless polyps are found or an individual has a family history of CRC. Unlike other routine screening tests (e.g., pap), it does not achieve the normalcy created by annual repetition (Bush, 2000).

The second approach that underpins our study is both theoretical and methodological, and aims to examine the meaning, process, and context of health. We adapted a participant-employed photography technique, known as Photovoice, which merges three theoretical frameworks (Wang et al., 1996): (1) community documentary photography to emphasize that people living in a community may offer images that better represent their experiences; (2) Paolo Freire’s education for critical consciousness to cultivate critical discussions about social justice issues; and (3) feminist theory and method to acknowledge and address the power hierarchies that affect knowledge production. Feminist theory, in particular, has been foundational to the development of the Photovoice method because of its acknowledgment that the experiences of marginalized populations tend to be overlooked in research and programmatic development, leading to the misrepresentation of their lives and needs (Wang, 1999; Wang & Burris, 1997). Feminist theorists have identified the significance of knowledge based on lived experience for understanding social issues. They advocate for “a form of knowledge construction that includes those who are the subjects of research” (Wang et al., 1996: 1392). In Photovoice, this is realized through participant-driven photographs, with the goal of having photographs and messages produced within such studies reach broader audiences of policy makers and practitioners to effect change.

Participatory photography has gained popularity in health disparities research since the 1990s and is used as a way to give individuals greater control over the research process and the production of knowledge about their lives (Wang et al., 1996). Photographic methods may also generate more detailed accounts of experience than conventional interview techniques (Frith & Harcourt, 2007). Researchers have used Photovoice to examine a variety of health issues related to physical and social environments (Bukowski & Buetow, 2011; Mahmood et al., 2012; Rhodes et al., 2008), health behaviors (Duffy, 2010; Hennessy et al., 2010; Valera et al., 2009), and the prevention and management of specific health conditions (Fitzpatrick et al., 2012; Kubicek et al., 2012). The studies in which researchers have used Photovoice to explore cancer disparities tend to focus on cancer survivorship (Lopez et al., 2005; Mosavel & Sanders, 2010; Yi & Zebrack, 2010), with very limited studies of treatment (Poudrier & Mac-Lean, 2009) or screening (Thomas et al., 2013).

Photovoice, we suggest, offers one means of addressing the power inequalities and methodological insufficiencies of previous qualitative work carried out on CRC screening, which has tended to rely on cross-sectional interviews or focus groups, using researcher-initiated questions. These techniques may not capture how people experience and ascribe meaning to CRC screening, and they may further exacerbate power differences between interviewer and interviewee (Castleden et al., 2008). Further, the rapid, hierarchical, and static nature of such work may simply generate “impression management discourses” (Messac et al., 2013), rather than insight into the meaning, process, and context in which individuals experience CRC screening. Combining the Photovoice method with theories of responsibilization of health care, we asked: How do people in medically under-served areas engage with processes of “responsibilization” in relation to a type of cancer that is considered preventable and a screening technology that is quite invasive?

Methods

Setting

Our project was carried out in St. Louis, Missouri, a city with pressing economic and health disparities. In 2011, 26 percent of the city’s residents were living below the federal poverty line, 19 percent had no health insurance, and 13 percent were unemployed. The number of city residents using the health care safety net for primary care has grown in recent years even though the city population has decreased (Regional Health Commission, 2012). Disparities in cancer survival in St. Louis are high. In St. Louis City, the death rate from CRC is higher than the overall CRC death rates in Missouri and in the United States (National Cancer Institute, 2014). Health providers in the region partially attribute these disparities to late detection and a lack of access to preventive screenings and CRC treatment. Colonoscopy is not usually carried out in primary care settings. The one local center dedicated to providing colonoscopies for Medicaid and uninsured adults filed for bankruptcy in 2013 and subsequently closed. People can go to area hospitals for colonoscopy, but there is no longer one central location for under/uninsured patients, and many hospitals are not central to the most heavily under-served areas in the city’s North side. This context raises questions about what it takes to successfully undergo screening and the experience of receiving a screening test.

The initial idea for this project came from members of the Colon Cancer Community Partnership (CCCP), a university-community partnership initiated in 2005 to address CRC disparities in St. Louis. The partnership consists of leaders from local organizations/institutions, community members affected by colon cancer, health care providers, and university researchers (including Hunleth, James, and McQueen). The partnership meets quarterly to offer feedback on CRC-related research and conduct outreach. In 2009, members expressed concern that cancer disparities research in our city had not adequately addressed the struggles faced and also obstacles surmounted by people who had been screened for CRC. This Photovoice study was proposed as one way to hear people’s stories of CRC screening and better understand the experience of screening for people living in under-served communities with longstanding disparities in cancer survival.

Recruiting Participants

To examine the experience of screening, we recruited individuals who had previously undergone screening, with no history of CRC diagnosis. We focused on people who had been screened because they are the “missing group” in the CRC screening and treatment literature. Rather than viewing their screening as unremarkable because they adhered to screening guidelines, we start from the position that understanding their experiences might help us improve the experience of CRC screening and offer insight into the obstacles faced by people who have not screened.

Our sampling strategy was purposive and broad. We recruited people age 50 years and older in accordance with current United States Preventive Services Task Force screening recommendations that suggest that adults should be screened starting at age 50. To ensure that our sample comprised individuals from underserved areas of St. Louis, we worked with the CCCP. Specifically, we created study advertisements to be distributed by the CCCP members and other community partners as well as at health centers. We also worked with a community recruitment resource at our university to distribute study advertisement information to individuals reached through the university’s outreach efforts. Interested individuals were asked to call our study staff, and the research team screened volunteer callers for eligibility. We asked eligible individuals about their available times and days, and when we had enough people with similar availability, we assigned them to one of three Photovoice groups.

Photovoice projects conventionally rely on small sample sizes, and we chose to keep our groups small for several reasons. First, we have learned in previous research that CRC can be difficult for participants to discuss in large groups. We anticipated that smaller groups would help participants reach a level of comfort and trust with each other and us that they needed to discuss their personal experiences. Second, showing and talking about photographs in front of a group can be a nerve-wracking experience for people who are not accustomed to engaging in artistic expressions or talking in front of a group. The small groups helped people reach a level of comfort and rapport with each other and the staff more quickly. Finally, we kept the sample small because our study included multiple interviews and discussions through time to facilitate a depth of understanding of the participants’ perspectives and lives not possible in larger groups. After working with the three groups, we felt the topics were saturated enough to move ahead with analysis.

Thirteen women and five men between the ages of 51 and 69 years took part in the study. Thirteen participants were Black and five were White. Many participants were unemployed or under-employed during the study and actively seeking work. A few participants reported receiving disability benefits. Thirteen participants provided information on their insurance types at the time of the study: seven participants received insurance through Medicaid; one person had Medicare; three people had private health insurance; and two people were uninsured. All participants had undergone colonoscopy at least once, most within the past five years. No one was diagnosed with CRC. However, several participants had polyps removed or were diagnosed with other gastrointestinal conditions (diverticulitis, Crohn’s, etc.) as a result of the procedure.

Study Procedures

The 18 individuals who enrolled in our study participated in three separate Photovoice groups. Each group had five to seven participants and lasted approximately 12 weeks, during which time we held a training session, three to four additional group meetings, and individual meetings with participants between the group meetings. The group sessions were conducted in a private room in the Health and Information Center at the University’s Cancer Center, a resource for patients, families, and community members that provides cancer information, support, and resources. While we originally planned to meet in a local library or community center, we eventually decided on the Cancer Center because participants identified it as the easiest location to get to because of the layout of public transportation in the city.

At the start of the first group meeting for each of the three groups, study team members reviewed the study procedures with each participant and obtained written informed consent. After the completion of informed consent, each participant received a packet with informational materials, schedule of meetings, and a digital camera. Group members and staff introduced themselves to each other, and each participant offered reasons why they were interested in participating in the study. Hunleth then gave an overview of the history and philosophy of Photovoice, the schedule of research activities, and anticipated outcomes of the project. The training culminated in a discussion of issues related to the ethics of photo-taking, including privacy and consent, and also an exercise in which participants learned about and used the digital cameras.

To offer direction on the photo-taking, we asked participants to choose, as a group, photo “assignments,” which we defined as broad topics related to CRC screening. The initial CRC-related assignment was derived from a facilitated group conversation about CRC and CRC screening, which focused on what screening meant to the participants and what types of things helped or hindered CRC screening. After deciding on an assignment, the participants spent two weeks taking photographs on their own. During the second week, they met individually with a research assistant to discuss all of their photos in an interview format that resembled photo elicitation methods (Harper, 2002). In this individual interview, they selected a photograph or photographs to discuss with their group.

When the group reconvened, we displayed photos on a large monitor and each member presented their photo(s). Presentations and group discussions were loosely guided by a series of questions about what the picture depicted, the story behind the picture, and how the photo related to the participants’ lives and to CRC screening (Wang, 1999). After everyone presented their photo(s), all photos were displayed side-by-side on the monitor. The participants then engaged in dialogue about the themes they noticed across the photos and a more generalized discussion of the meanings of the photos in relation to their experiences. Based on this discussion, the participants decided on their next assignment. The photographs, therefore, helped focus the discussions, and the discussions influenced the next round of photo-taking. We ensured that, by the time of our final group meetings, participants were satisfied that they had exhausted all topics on or related to CRC screening. We added an additional group session for Group 1 upon their request when they said that they still had one more topic to discuss.

The discussions during the group meetings were lively and sessions were well attended. Eleven participants came to all scheduled group meetings. Four participants missed one group meeting, two participants missed two group meetings, and one participant had to withdraw from the study after the training session due to a family crisis. The participants who missed one to two sessions reported conflicts with work or job interviews and also health and transportation issues as their reasons for not attending.

Analysis

This project generated a lot of data: transcripts from the audio-recorded group and individual sessions; field notes written after each group and individual meeting to document the process, emerging themes, group dynamics, tone, interactions, body language, and aspects not captured on the audio recorders; and the participants’ photographs. Our analysis focuses on transcripts of the audio-recorded discussions that took place during the group sessions. The detailed field notes taken after each group session and the audio-recorded individual interviews further inform our interpretation. Hunleth and James led the analysis, with the assistance of two coders, and using techniques from grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The team met regularly to develop the codebook. Once the codebook was finalized, two research assistants each coded all transcripts using NVivo 10 (Richards, 2005). During the coding process, the coders met weekly to compare their coding and to resolve inconsistencies. The discrepancies in coding were minor, and Hunleth and James assisted the coders in resolving them. After the coding was complete, we convened a series of team meetings with the coders in which we discussed the meanings and interpretations of the coding categories.

Recruitment, informed consent, and study procedures were approved by Washington University’s Institutional Review Board. All names of participants used in this article are pseudonyms.

Results

The participants found common ground in their belief that screening for CRC was, in general, an important and “proactive” way to remain healthy. They were, however, wary of making judgments about people who had not been screened and understood that each person has different experiences of and struggles with CRC screening. This acknowledgment of the struggle and the diversity of experiences shaped the ways in which the participants talked about and perceived the photos they took. No singular photo, they suggested, could represent the complexity and diversity of their experiences with CRC screening. Instead, the participants viewed their photos as metaphors, they extended their stories well beyond the scene or object that they had photographed, they were open to discussion about differing experiences, and they sometimes made linkages among all of the photos taken by the group. The photos became springboards for deeper, richer conversations than might otherwise have happened without the photographs. However, this form of discussion also made it difficult for them, or us, to reduce the content and messages they conveyed to a singular photographic image. For example, a photograph of a woman sleeping peacefully in bed prompted a lengthy discussion about the struggles of balancing work responsibilities with the colonoscopy preparation and procedure.

In this results section, we identify the main categories that emerged from the group discussions of the photos. Because the conversations tended to go more in-depth and migrate away from the photos, we give more attention in this paper to the discussions that took place than to the photographic images. We believe that this means of presenting the results more accurately captures what the participants were conveying to each other and to us during the sessions. We also acknowledge that participants sometimes broadened their discussion to other health topics as a way of talking about CRC and CRC screening. In what follows, we break the results section into three main sections. First, we identify struggle as a main category used to talk about CRC screening, and we highlight the different aspects of the struggle to get screened. Second, we highlight a core category that the participants suggested was key to successful screening: social connections and support. Finally, we identify CRC screening as an emotionally-laden process—including before the initial test and after the results are received—that is underpinned by feelings of uncertainty, guilt, fear, and sometimes relief.

Ways in which participants experienced CRC screening as a struggle

We identified several ways in which the participants experienced CRC screening (or receiving a colonoscopy) as a struggle. First, the participants discussed the high monetary cost of the colonoscopy procedure, which makes it prohibitive without insurance coverage or other forms of outside support. Second, they revealed extra and hidden costs associated with screening beyond the medical bills. Third, the participants stressed to us that the limited information available to them about CRC, CRC screening, and resources for CRC prevention and treatment placed constraints on their ability to make health care decisions and remain healthy.

Insurance coverage shaped and constrained attempts to seek screening

Participants pointed out that the cost of colonoscopy was difficult to afford without insurance or other forms of medical assistance. Many participants shared their experiences with going on and off of insurance. They suggested that not having insurance for periods of time delayed screening attempts and could lead to substantial medical bills and debt. Many participants indicated that obtaining and retaining insurance coverage was a struggle due to job loss, divorce, and other life events. For example, Anna took a photograph of a pile of bills, still in their envelopes and with coins spread across them to represent limited money to pay them. She used this photo, in part, to speak about the challenges of finding insurance after losing coverage on her husband’s plan following their divorce. Though she was working, she did not have insurance benefits, and she was forced to take an additional job to access an employer-provided insurance plan. Even with insurance, she had little money left to pay for health care after she paid for her most basic needs.

Participants worried about unexpected bills from the colonoscopy procedure. This fear is, in part, due to the vagaries of medical billing that make the cost of colonoscopy vary depending on whether or how many polyps are found and biopsied. In other words, there is no way to know the exact cost up front. As one participant phrased his fear of the unknown expenses: “I know I had insurance, but I didn’t know if I had enough insurance… I’m on Medicaid. I got the red card. You know they can’t come up with all the monies on the insurance.” Fortunately for him, he had supplements that covered his expenses. However, the knowledge that his insurance might not be “enough” meant that he faced a lot of uncertainty about what his bills may be and whether he could afford them.

Unstable, nonexistent, or limited insurance coverage caused participants and their family members to put off screenings. Another participant, Ruth, spoke at length about a relative who had never been screened for CRC because she did not have insurance coverage. Ruth was concerned about her relative’s health and told us that her relative was waiting until Medicare age (65 years) to get her first colonoscopy. Considering their family history of CRC, Ruth reasoned, “[Our relatives] actually die [of CRC] in their 70s and she is only 56 so she thought, ‘well, I got time.’” Alternatively, some participants discussed efforts to get screenings and preventive health care even without insurance, but these efforts also had consequences. Nanette, for example, talked about how lapses in insurance coverage led her into medical debt when she tried to stay up to date with her preventive care. She said:

It took me almost two years to get insurance for myself. The only bills I got is from the hospital, going back and forth to the hospital, and now they talking about cutting stuff [i.e. services and coverage]. I feel like the old lady who says, ‘Should I get food or should I pay a bill or buy cat food.’ It was a joke but now it’s true. Like people got air conditioners but they can’t pay the bill, or they won’t turn on their heat because they got bills.

Her comments demonstrate how medical debt incurred while getting preventive health care in the absence of insurance can lead to future trade-offs (paying bills or buying food) that can, in turn, affect health and wellbeing.

For some people, an inability to get screenings and other preventive care meant that they had to wait until they were sick, at which point screening became diagnostic. One participant illustrated this point as she recounted her daughter’s difficulties in accessing a diagnostic colonoscopy. Her daughter was experiencing some gastrointestinal problems, which she worried were related to their family’s health history. She said: “We are still trying to figure out how to get her to get a colonoscopy because they are not that easily accessible. Basically what she is going to have to do is wait until she gets sick, go to the emergency room and see what they will do for her at the end. There is no place that pays for them up front.”

The above stories describe some of the efforts and trade-offs that some people make to receive a colonoscopy without insurance coverage, such as waiting until Medicare age or sickness, working a second job, and/or possibly accumulating medical debt. As we will discuss, the participants were aware of the health risk of delaying and even small delays in health care heightened their worries about having cancer.

Colonoscopy procedures include extra costs

Participants explained that the costs of colonoscopy went well beyond the actual price tag on the test. Anna, whom we mention above, indicated that one hidden cost of any health care related to the amount of money that an employee must pay toward their coverage. She explained: “You have to work an extra day if they are taking [premiums] out of your check.” As a result, Anna was exhausted from working two jobs just to have insurance, and having insurance did not eliminate her financial concerns because she still worried about the total cost of medicine and procedures.

Beyond the cost of insurance and unexpected hospital bills, colonoscopy includes other expenses, which the participants discussed. These extra expenses include the cost of the “prep” solution needed to clean out the colon, the need to find one’s own transportation to and from the hospital, and the time used to prepare for and undergo the procedure. Describing her difficulties with CRC screening, one participant indicated that the hardest part for her was “The time, you know, because you have to take off two days of work. You can’t work the day before and you can’t work the day of.” This challenge resonated with other participants, who said the CRC screening process was particularly costly for individuals who worked in part-time and hourly jobs that did not offer paid time off.

Some participants said that they carried out the prep and fasting at work because they could not take both days off. This was not only embarrassing when they had to use the toilet frequently; it was also extremely challenging and bore its own health risks. Millie was one such participant who had to work two shifts in a strenuous job before her scheduled colonoscopy. She used a photograph of herself sleeping peacefully to explain how she felt after her long struggle to get screened. She started her story, “I had worked a double and so that made me hungry, and I got to eat when I’m working that hard.” She knew that she was not supposed to eat while preparing for the colonoscopy and, when she went for her colonoscopy, she told the doctor that she had eaten a sandwich: “They took me anyway…I did the whole thing [colonoscopy], but like I said they couldn’t accept it [i.e. they could not get a clear view of the colon walls] because I wasn’t cleaned out. So I really panicked with that…I said, ‘Oh I messed that up.’” Because the doctor could not adequately view the walls of her colon to ensure that she did not have polyps, he asked her to return for repeat colonoscopy the following week. During that procedure, they found and removed a polyp, and she was greatly relieved. Her relief or, to use her words, her “peace of mind,” was heightened by the difficulties she had to surmount to get screened and her first incomplete colonoscopy.

Millie’s story demonstrates the struggle to get screened when a person has to balance screening demands with their other responsibilities, such as work or, as described by some participants, taking care of children, grandchildren, and other dependents. In the end, Millie was forced to take more time off work to repeat her colonoscopy, and having two colonoscopies in two weeks increased the costs and the risks of complications that come with the procedure. Her case demonstrates that screening can be more expensive and burdensome for the same people who have trouble affording or accessing screening in the first place.

Information about CRC is limited and limiting

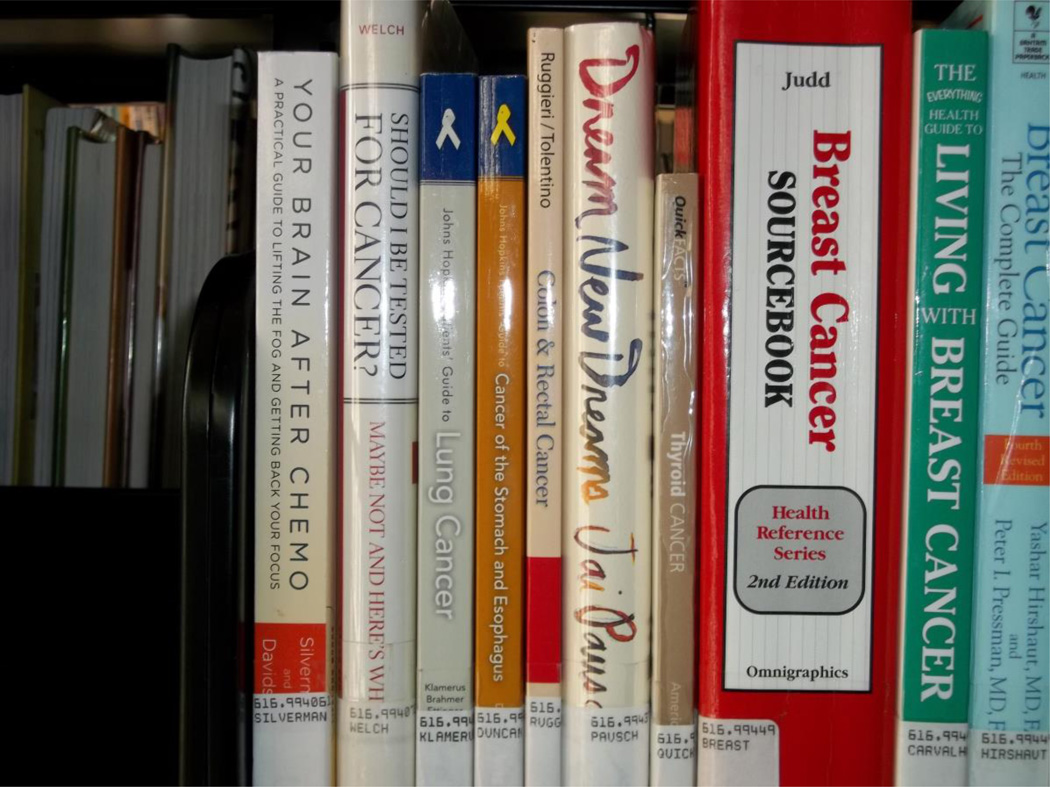

The participants emphasized how limited their access was to information on CRC and CRC screening. They also noted that information about financial assistance for screening and treatment was not easy to find. To highlight the absence of available information on CRC, Lillian photographed a library shelf. Showing the picture to her group, Lillian explained: “That’s the only book for colon cancer that was in the library over here.” She pointed to the photo so that people could see it on the shelf between other books on cancer. “It’s that little bitty book…Next to the yellow one.” She went on to explain that other cancer types did not have many books either. Her critique was made at two levels. First, libraries were a main source of information for participants who did not have access to the Internet. One participant said that she did not know anyone who owned a computer. Therefore, the lack of information in the library created a real barrier to learning about CRC and CRC screening. Second, the picture of the book shelf also served as a metaphor for the lack of information and informed discussion on CRC in general. Participants suggested that there was a lack of information on the Internet and at their doctor’s offices. When information was available, they said, it was often not detailed enough, was written in inaccessible language, or restated basic information that they already knew. In one participant’s words, “What little there is just seems to be very basic and repetitive.”

The participants suggested that the absence of detailed and accessible information placed limits on a person’s ability to take charge of their health. Many participants said that they felt constrained in what they could do to prevent CRC because of a dearth of information about prevention. In discussing photos they took of exercising and healthful foods, the participants noted that, in one woman’s words, there were “not a lot of specifics…about what you can do to avoid it, what you should do if you are afraid about it.”

For some participants, the lack of knowledge about resources to help with screening limited their agency. Reflecting on the distribution of resources for CRC screening and treatment, one woman suggested that there were resources out there, but that it took tremendous effort to find them. She suggested that “People got to open up and ask because, if you really don’t, people just ain’t going to say: ‘Oh, yeah, by the way, you can go down to so and so [to get help].’” However, given the limits to readily available information about CRC, it was difficult for participants to even know what to ask. Mary emphasized this point when she told us that she only recently learned that CRC affected women as well as men. Mary took pride in keeping up with her screenings. Her careful attention to preventive care shaped her identity: “You know we [her family] go and get our tests for blood, high blood pressure and everything else, a Pap smear, mammogram…” However, she had not been up to date on CRC screening: “Like I said, last year was my first time I ever got tested. My son had gone and got his [colonoscopy] and he came back and said, ‘Mom, you better get it too.’ I said, ‘That’s for men, you know?’ … And I didn’t know. I ain’t kidding.” She was already going to the doctor and “getting everything else,” which was something that she prided herself on. The realization that she had not known that CRC screening was also for women deeply concerned Mary because she could have missed something. In her words: “I’m so glad I found out, it could have been too late.”

Many participants felt that information about their test results, future risks of CRC, and CRC prevention was limited. In the words of one participant:

When I did get the test done, well the doctor was gone [when] they was waking me up to say it’s over. So I never knew what [the colonoscopy image] was supposed to look like and the nurse gave me a booklet. I got home and I started reading the booklet and I just, to me everything I read said I had colon cancer because you know the picture in the book, and that’s all I seen. And I’m like, “why didn’t he tell me?” You know and I’m on the phone trying to get him, and I was crying because I had it. But I didn’t [have cancer]. It was just a booklet. I didn’t even see the side that say you didn’t have. I just seen the side that said I had it.

This confusion after the test was familiar to several participants, who also had questions about their colonoscopy images. As one woman suggested: “Instead of sending those pictures to me, I want [doctors] to tell me, to come in and talk to me about it.” Some participants even brought their colonoscopy pictures to the group meetings and individual sessions and asked for help understanding the results.

Social connections and support as a necessity before, during, and after screening

Participants continually pointed to the reality that their screening would not have been possible for them without the social connections or support of a range of people, including family members, friends, church members, social workers, and doctors. This social basis of screening was evident in a photograph that John took of a framed painting of flowers. On top of the frame, he had spelled out his partner’s name in blue and green pipe cleaners. He explained: “I made that and put that name up. That’s in my bedroom because she was there for me when I went to the doctor, made sure I went to the doctor to get my colonoscopy. All they did, she stuck by me.” John emphasized that his partner’s support was what compelled him to get screened. Other participants agreed with John. For example, Angela said that, at first, she had not wanted to go through the procedure: “My doctor advised me to have a colonoscopy…I refused at first, but after many family discussions I took the test.”

The participants identified that family and friends shared the costs and labor of CRC screening. Family and friends assisted the participants with the preparation and transportation and took time off work to accompany them to the procedure. Angela, who mentioned that she “refused” to get a colonoscopy at first, photographed a woman sitting at a kitchen table to represent the support her family gave her. She explained to the group that the photo represented support: “That’s my sister and she was very supportive when I went to have my colonoscopy…She kept up with the time and she did most of the [prep] mixtures…And she made sure I ate a good meal the day before I had to start preparing for the colonoscopy.”

The participants suggested that what set them apart from people who had not been screened was the support that they received. One participant emphasized this point when she said: “Not everybody has someone who could take time off. I don’t know what people do who don’t.” In addition to discussing the importance of family and friends to their own screening process, many participants also viewed themselves as involved in the preventive health care of people they knew. They related this to the difficulties in getting information and resources for screening, and also to the policies and practices around CRC screening that expect a person to have social support. To receive a colonoscopy in the United States, a person must be accompanied by an adult. In accordance with most hospital protocols, patients are sent home directly after the colonoscopy, while the anesthesia is still in their system, and many facilities will not begin a procedure unless the patient’s escort is present. This policy shifts post-procedure responsibility for the patient from the medical facility to an individual’s social network.

Participants included health professionals as important connections and possible sources of support. To emphasize this point, one participant shared a photo she had taken of a doctor comforting a patient and, at the same time, giving the patient information. In discussing changes to the health care system that might facilitate adherence to CRC, one woman suggested that doctors could come together with family to comfort both the family and the patient. Other participants suggested that they wanted health care providers to be more supportive of them and to treat them as more than just body parts—as whole persons with histories, families, emotions, and a range of physical and spiritual needs. Identifying the limits of familial support, one participant suggested the option of overnight hospitalization during pre-test prep, which for her would alleviate some of the work and obligations (familial or otherwise) that interfere with completing the procedure as well as help people who do not have someone to care for them or take them to the hospital. Her suggestion points to the extreme circumstances that some people face—living in a crowded home with just one bathroom, the demands of caring for young children, or workplaces that do not allow time off for the prep phase of the procedure—and shows that shifting some responsibility back onto hospitals and physicians could help some patients with adherence.

CRC screening is laden with emotions

The participants described CRC screening as laden with fear, guilt, stress, relief, uncertainty and other emotions. These emotions were not easy for us to disentangle in the participants’ discussions of screening, and we developed this category as a way to do justice to their accounts and contextualize the emotions they expressed. One strong pattern we identified was the linkage of lived experience of cancer to fears and uncertainties about screening. The screening process heightened participants’ memories of people they knew in their communities or among family and friends who had suffered from cancer. These memories predominantly focused on quick death after diagnosis and also on the financial strain and also the guilt, blame, sadness, and fear that resulted from cancer deaths. Take for example Nanette who, in an extended account, talked about her grandmother and husband:

The first time I was introduced to cancer was my grandmother… She wanted to put a light bulb in, and she fell and that’s how I found out she had cancer…When I found out my husband had cancer…He had a bump on his back, and I kept telling him, “Let’s go to the doctor, let’s go the doctor.” When we did get there it was too late...And come back to the fright of going [to the doctor]. I got frightened after that.

Part of Nanette’s “fright” related to seeing her family members suffer and die quickly. She also linked her fright to no longer having the support of her husband because he had died. Nanette later mentioned young people she knew who had died from cancer, without knowledge of their disease until it was too late. Such stories recurred repeatedly during the study. The participants’ negative encounters with cancer may suggest that we had a select group of participants that do not represent the broader St. Louis community. However, we suggest, instead, that the absence of survival stories reflects the larger economic and health care disparities that have shaped cancer morbidity and mortality in our city and around the country.

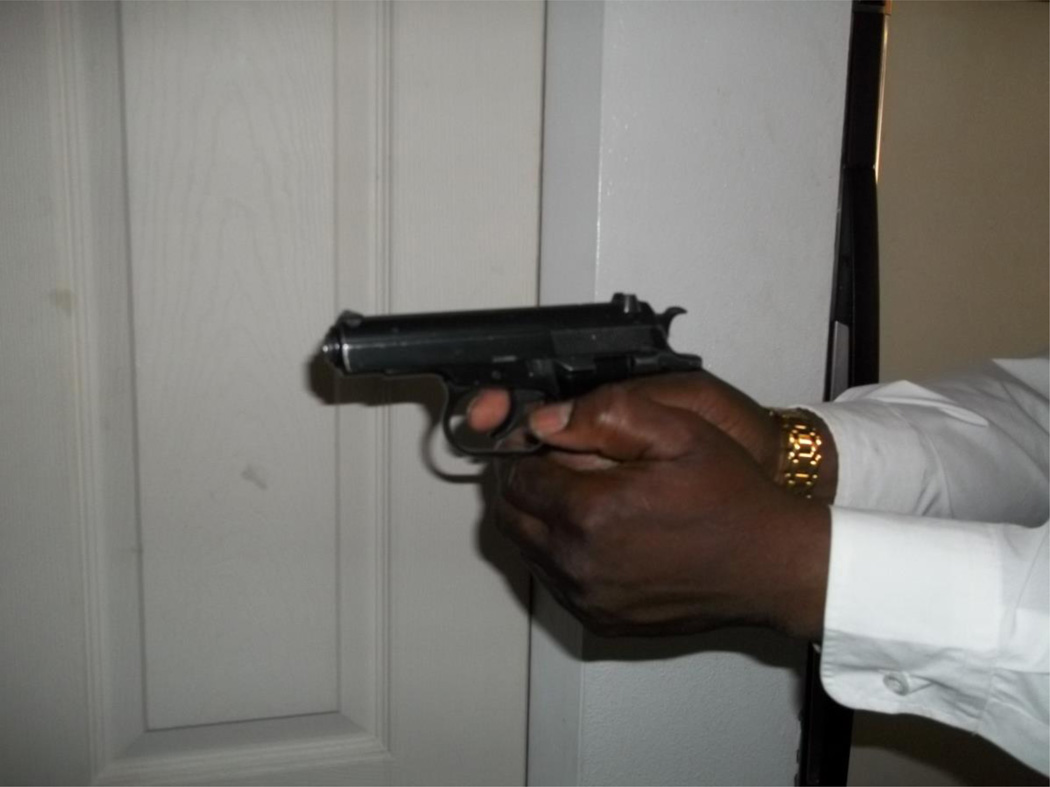

Many participants’ stories provide insight into their feelings of ambivalence about cancer screening. The frequency of their family members’ encounters with cancer, often with negative outcomes, inspired them to get tested and to encourage their loved ones to also test, as they intimately understood the importance and urgency of timely cancer screenings. They perceived frequent screening as a way to minimize costs, prevent cancer, and remain healthy for their loved ones, including grandchildren. Still, fears of a cancer diagnosis made the testing process especially stressful. Their lived experiences suggested that screening might identify late stage cancer or even early stage cancer that they and their families could not afford to treat. To represent the link between screening tests and cancer diagnoses, Esther photographed the hand of a man holding a gun. The gun symbolized the dramatic effects of diagnosis, which she related to her personal experiences: “This photo makes me feel like my life can be taken away like a bolt of lightning. My personal connection is that my father had pancreatic cancer, and he found out and he only lived three months.” Thinking about her father’s death and the emotional and financial impact of cancer on her family made Esther fearful of screening, but it also compelled her to get screened.

The observations that participants made in their daily lives conflicted with the optimistic screening messages put out by medical and public health organizations. These messages include the repetition of phrases—such as early detection (or screening) saves lives and CRC is preventable—in screening campaign programs and materials. Even though they saw and heard these messages frequently, including on buses on the way to our group meetings, participants felt great uncertainty about the outcome of screening because of their experiences with family members and friends who had cancer. They also expressed great relief when a preventive screening test did not reveal cancer. Lillian acknowledged this point when she admitted to her group that she had not wanted to be screened. She was “not fond of doctors,” and she did not want to become dependent upon them or medications and treatments that she could not afford. She reasoned that all of her relatives die young and most of her family was already “gone.”

Participants expressed strong motivations to encourage or compel family or friends to get screened. They linked this imperative to their memories of and regrets over deaths in their families: “Sometimes we thought, ‘if we had the money and made them go to the doctor, they wouldn’t have waited and thought they couldn’t go because they didn’t have the finances to go [get screened]…They wait too long [to get the test]. The test is over with, and we know they going to go [i.e. die]. They might go in two weeks. Mine went in six weeks. My husband went in six weeks.” Not being able to convince a loved one to get health care caused “pain,” “stress,” “anxiety,” and “anger,” and also reflections about the role they could or should have played in getting a family member screened.

The accounts provided by Lillian, Esther, and other participants demonstrate that a colonoscopy was not just a procedure and, while brochures and other information discuss the preventive benefits of CRC screening, many participants had seen and experienced otherwise. As they demonstrated, these negative stories created uncertainty and stress, even when such stories also compelled them to get themselves and their loved ones screened.

Discussion

As government involvement in health care has changed under neoliberal reforms, individuals and their families have become increasingly saddled with the responsibility for maintaining their own health and wellbeing, which includes practices such as purchasing insurance, receiving preventive care, and saving for retirement. The heightened focus on individual responsibility ignores and also exacerbates the broader landscapes of inequality that play out along race, class, and gender lines (Harvey, 2005). By attending to this social, political, and economic context, we can better understand the ways that people’s behaviors and beliefs are tied to the broader conditions. Through their photographs and discussions, participants highlighted a variety of ways that responsibilization shaped their access to, and experience with, CRC screenings.

Even though all participants had received colonoscopies, they emphasized the financial costs of CRC screening. Many who live with economic insecurity cited myriad difficulties in acquiring and maintaining health insurance, as well as uncertainties about whether insurance would fully cover the procedure and anything needed as a result (biopsy, surgery, cancer treatment). The Affordable Care Act now mandates that insurance plans cover screening. However, this mandate does not include diagnostic testing or pathology (Green et al., 2014; Pollitz et al., 2012). Given the extra or hidden costs as described by the participants in our study, simply covering screening is not likely to close the disparity gap. This suggests that the conversation about insurance must go beyond discussing coverage versus lack of coverage to understanding the ways in which unstable or inadequate insurance coverage affects the way people access health care. The participants pointed to the need for transparency in costs of the test, polyp removal, future treatment, and the problems created by unstable insurance coverage. Having insurance did not ease participants’ concerns about how they would pay for medical care if screening led to a cancer diagnosis. Their fears are well-founded given that approximately 20 percent of Americans struggle to pay their medical bills (statistics from 2011 and 2012) (Cohen et al., 2013).

This study demonstrates that cost is a concept that stretches beyond the medical bill for procedures. Costs can include the loss of wages resulting from unpaid time off of work for preparation and the colonoscopy procedure. They can also encompass the social costs that might accompany a cancer diagnosis. Participants considered what a cancer diagnosis might require from them and their families and how it demanded that they engage in particular practices, including increased involvement with medical interventions and treatments or how medical intervention may limit their ability to live a decent life. They expressed these multiple costs and considerations through talk of the fear that screening evoked. Fear is a common psychological construct discussed in the CRC screening literature as a barrier screening (Bynum et al., 2012; Green et al., 2008; James et al., 2008). The participants showed the complexity of this construct and its socioeconomic underpinning. Their fears were rooted in past experiences of loss and coupled with the very real concern of the burden that their own illness might place on them and their kin—people who were also living with economic insecurity. These past and envisioned future losses affected their approach to screening, as they evaluated their ability to adequately achieve their present and future health needs in the absence of stable insurance, resources, or public supports that might aid them.

The participants made clear that they actively calculated the costs of health care as a whole, rather than looking at a single procedure such as colonoscopy. They weighed these costs against available resources (e.g. insurance, transportation, household income, social networks). This calculus took various forms. In some cases, it meant extreme attempts to follow medical advice and access technology as a means of ensuring against poor (or poorer) health in the future. This included arduous, time-consuming quests for information and resources. Participants detailed hours spent in libraries and efforts by themselves and their family members to identify free screening opportunities and screening resources. They gave accounts of how they must fiercely advocate for themselves and loved ones. That some people joined our Photovoice groups to access information for their health and the health of family members is telling of the time and labor it takes to acquire resources when one is poor. It shows the need to creatively access information and resources that they are not readily available.

Achieving an ideal level of “adherence” to all medical guidelines appeared to be nearly impossible. The participants showed that they had to weigh evidence from their quests for information and everyday experiences and make hard decisions about their health care needs. They engaged in cost-coping strategies identified in other studies, such as cutting medication, prioritized some preventive tests over others, and going into debt (Berkowitz et al., 2014; Heisler et al., 2005; Piette et al., 2006). Such tactics were quite explicit and acknowledged in some discussions, such as when a mother spoke about needing to wait until her daughter’s condition worsened in order to get her a colonoscopy that did not require payment upfront, or when a woman said that she had to choose between eating to sustain herself at work or fasting for a colonoscopy. Such improvisation may not always be so conscious, though. Rather than labeling such improvisation as “non-adherence,” we interpret such behavior as extreme measures to prioritize resources for maximal health benefit or daily living needs. This view leads to a more complex picture of health seeking than the current binary ones in which individuals are seen as either good patients or bad patients, as adhering to guidelines or not. This begs for more understanding and empathy from health care researchers, physicians, and policymakers to not simply label patients as nonadherent (Gignon et al., 2013).

In the current moment of increased individual responsibility for health, people from under-served communities suffer specific consequences. As the participants have shown, they may actually perform considerably more labor (accessing transportation, taking unpaid leave from work, searching for information, and navigating the confusing health care landscape) for their health care than the rich. This finding is consistent with the observations of other anthropologists that maintenance of daily life requires extra labor from poor people, whose access to transportation, employment, food stores, information, and other services are generally more restricted (Collins & Mayer, 2010; Stack, 1974; Williams, 1988). Furthermore, because responsibilization has become a pervasive ideology, the participants internalized individual responsibility imperatives even as they critiqued them. For instance, they expressed shame for not taking responsibility for their own health care, despite acknowledging the constraints and limitations that prevented them from adhering to all medical advice.

In discussing social support, the participants acknowledged that cancer is a disease that happens between people (Livingston 2012). The neoliberal rollback of public supports and increased burdens on individuals and families in the United States and other countries has created new forms of reliance and stresses on social and familial relationships (see Biehl, 2005). Most participants suggested that a robust network of friends and family who advocated for their screening through words (e.g., family discussions to encourage a person to get screened) or presence (e.g., wanting to be around for grandchildren) and made it logistically possible (e.g. transportation, help with household responsibilities) was what separated them from the people they knew who did not get screened. Some participants discussed their own feelings of anger and guilt when loved ones died, questioning whether or not they and their deceased loved ones “did enough.” They showed that such tragedies compel them to push family members and themselves to receive screenings, shifting the labor and stress of cancer prevention even further onto family members and social networks. This familial management of screening may have a number of repercussions and effects on relationships that we could not identify within the constraints of the method.

Our analysis has further limitations. First, the participants were a select group who wanted and had time to join a Photovoice study on CRC screening. Many were motivated by their experiences with cancer in their families. Second, all participants had been screened using colonoscopy, which excludes a view of lower-technology and less expensive screening modalities but corresponds with the screening environment in the United States (McQueen et al., 2009; Zapka et al., 2012). Finally, the location of the group meetings in the Health Information Center at the Cancer Center, rather than a different community location, likely influenced the direction of the photographs and discussions.

Conclusion

The findings from this Photovoice study offer important information for practitioners, researchers, policymakers, and other groups that allocate CRC resources and design CRC educational materials. First, behavioral science researchers have rightly pointed out that perceived costs affect people’s approaches to CRC screening and care (Doubeni et al., 2009; Doubeni et al., 2010; O’Malley & Mandelblatt, 2003). A common response to this finding is to suggest that educating patients about the benefits of a procedure can reduce the perceived cost. While in some cases this may be true, it also minimizes the struggles that individuals and families go through to access health care and how they consider their choices within their broader social, economic, and familial contexts. Second, current public health and biomedical interventions for CRC—particularly ones that situate patients as “informed consumers” and autonomous agents—do not allow for the complicated ways that people navigate their social, economic, and medical worlds simultaneously. For example, decision aids and other materials emphasize individual decision-making and personal responsibility (Legare et al., 2014; Stacey et al., 2014). By advancing responsibilization rhetoric, such educational and decision-making materials, in the absence of structural supports, may alienate people and contribute to their blame, guilt, or shame for delaying screening. Third, many research participants showed that they were already striving to take responsibility for accessing CRC screenings and information, despite substantial barriers. Their attempts were not always fruitful. The acknowledgment of the effort to achieve health care and adhere to medical guidelines, and also the many forms that such effort takes, should be the subject of further research and interventions. Understanding such efforts has important implications for physician recommendations, preventive health care communication, and the organizational delivery of care to under- and uninsured patients.

Figure 1.

Anna took this photograph to illustrate the number of bills she receives and the limited money she has to pay them. She paired this photograph with another photo of medication to represent the difficulty of paying for medical bills.

Figure 2.

Lillian photographed a bookshelf in a local public library to show the lack of readily available information on CRC and CRC screening.

Figure 3.

Esther took this photograph of a gun to represent the feeling that cancer can take life away “like a bolt of lightening” and also the fear she faced when going for CRC screening.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 18 individuals who participated in this study. We also thank our research assistants, Natasan McCray, J. Kyle Cooper, Nancy Mueller, Rebekah Jacob, Emily Kryzer, and Kelsey Bobrowski for their contributions to the study.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA147794, PI: James). Drs. Hunleth and James were supported by the Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities, a Community Networks Program Center (U54 CA153460 PI: Colditz). Funding also came from the Barnes Jewish Foundation and Siteman Cancer Center. Dr. McQueen was also supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society MRSG-08-222-01-CPPB.

Biographies

Jean M. Hunleth, PhD, MPH, is a postdoctoral research associate in the Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Emily K. Steinmetz, PhD, is an assistant professor of anthropology at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA.

Amy McQueen, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Aimee S. James, PhD, MPH, is an associate professor in the Division of Public Health Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Albano J, Ward E, Jemal A, Anderson R, Cokkinides V, Murray T, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2014. Atlanta: The American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bass SB, Gordon TF, Ruzek SB, Wolak C, Ward S, Paranjape A, et al. Perceptions of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Urban African Americans clinic patients: Differences by gender and screening status. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002. e303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehl J. Vita: Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski K, Buetow S. Making the invisible visible: a Photovoice exploration of homeless women's health and lives in central Auckland. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush J. 'It's just part of being a woman': cervical screening, the body and femininity. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:429–444. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum SA, Davis JL, Green BL, Katz RV. Unwillingness to participate in colorectal cancer screening: examining fears, attitudes, and medical mistrust in an ethnically diverse sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26:295–300. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110113-QUAN-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H, Garvin T, Huu-ay-aht First Nation Modifying Photovoice for community-based participatory Indigenous research. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1393–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. New Labour's citizens: activated, empowered, responsibilized, abandoned? Critical Social Policy. 2005;25:447–463. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Kirzinger WK, Gindi RM. [January 2011–June 2012];Problems Paying Medical Bills: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey. 2013 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/problems_paying_medical_bills_january_2011-june_2012.pdf.

- Collins JL, Mayer V. Both Hands Tied: Welfare Reform and the Race to the Bottom in the Low-wage Labor Market. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Reed G, Field TS, Fletcher RH. Socioeconomic and racial patterns of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees in 2000 to 2005. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2170–2175. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Young AC, Klabunde CN, Reed G, Field TS, et al. Primary care, economic barriers to health care, and use of colorectal cancer screening tests among Medicare enrollees over time. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:299–307. doi: 10.1370/afm.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew EM, Schoenberg NE. Deconstructing Fatalism: Ethnographic Perspectives on Women's Decision Making about Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2011;25:164–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy L. Hidden Heroines: Lone Mothers Assessing Community Health Using Photovoice. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11:788–797. doi: 10.1177/1524839908324779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BK, Noone A-M, Mariotteo AB, Simard EP, Henley SJ, Jemal A, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1290–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AL, Steinman LE, Tu SP, Ly KA, Ton TG, Yip MP, et al. Using photovoice to understand cardiovascular health awareness in Asian elders. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:48–54. doi: 10.1177/1524839910364381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith H, Harcourt D. Using photographs to capture women's experiences of chemotherapy: reflecting on the method. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1340–1350. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignon M, Ganry O, Jarde O, Manaouil C. Finding a balance between patients' rights, responsibilities and obligations. Med Law. 2013;32:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AR, Peters-Lewis A, Percac-Lima S, Betancourt JR, Richter JM, Janairo MP, et al. Barriers to screening colonoscopy for low-income Latino and white patients in an urban community health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:834–840. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0572-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BB, Coronado GD, Devoe JE, Allison J. Navigating the murky waters of colorectal cancer screening and health reform. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:982–986. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths F, Bendelow G, Green E, Palmer J. Health. Vol. 14. London: 2010. Screening for breast cancer: Medicalization, visualization and the embodied experience; pp. 653–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths F, Green E, Bendelow G. Health professionals, their medical interventions and uncertainty: A study focusing on women at midlife. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1078–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harper F, Nevedal A, Eggly S, Francis C, Schwartz K, Albrecht T. "It"s up to you and God': Understanding health behavior change in older African Americans survivors of colorectal cancer. Translational Behavorial Medicine. 2013;3:94–103. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Wagner TH, Piette JD. Patient strategies to cope with high prescription medication costs: who is cutting back on necessities, increasing debt, or underusing medications? J Behav Med. 2005;28:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-2562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E, Kraak VI, Hyatt RR, Bloom J, Fenton M, Wagoner C, et al. Active living for rural children: community perspectives using PhotoVOICE. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton S, Abadia C, Mulligan J, Thompson JJ. Critical Anthropology of Global Health “Takes a Stand” Statement: A Critical Medical Anthropological Approach to the U.S.'s Affordable Care Act. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2014;28:1–22. doi: 10.1111/maq.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AS, Daley CM, Greiner KA. Knowledge and attitudes about colon cancer screening among African Americans. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35:393–401. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AS, Hall S, Greiner KA, Buckles D, Born WK, Ahluwalia JS. The impact of socioeconomic status on perceived barriers to colorectal cancer testing. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008;23:97–100. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07041938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Devers KJ, Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Beyer W, Weiss G, Kipke MD. Photovoice as a tool to adapt an HIV prevention intervention for African American young men who have sex with men. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:535–543. doi: 10.1177/1524839910387131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Cossi MJ, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke T. ‘The birth of bio-politics’: Michel Foucault’s lecture at the Collège de France on neo-liberal governmentality. Economy and Society. 2001;30:190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:99–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A, Chaudhury H, Michael YL, Campo M, Hay K, Sarte A. A photovoice documentation of the role of neighborhood physical and social environments in older adults' physical activity in two metropolitan areas in North America. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1180–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin JM, Weiner D. Confronting cancer: metaphors, advocacy, and anthropology. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Bartholomew LK, Greisinger AJ, Medina GG, Hawley ST, Haidet P, et al. Behind closed doors: Physician-patient discussions about colorectal cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:1228–1235. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Tiro JA, Vernon SW. Construct Validity and Invariance of Four Factors Associated with Colorectal Cancer Screening across Gender, Race, and Prior Screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2231–2237. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry SE. Relating to the Subject of Human Rights: The Culture of Agency in Human Rights Discourse. In: Freeman M, Napier D, editors. Law and Anthropology: Current Legal Issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Messac L, Ciccarone D, Draine J, Bourgois P. The good-enough science-and-politics of anthropological collaboration with evidence-based clinical research: Four ethnographic case studies. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;99:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosavel M, Sanders KD. Photovoice: a needs assessment of African American cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28:630–643. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2010.516809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. State Cancer Profiles: Death Rate Report for Missouri by County, death years through 2010. National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley AS, Mandelblatt J. Delivery of preventive services for low-income persons over age 50: a comparison of community health clinics to private doctors' offices. Journal of Community Health. 2003;28:185–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1022956223774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham: Duke University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Heisler M, Horne R, Caleb Alexander G. A conceptually based approach to understanding chronically ill patients' responses to medication cost pressures. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitz K, Lucia K, Keith K, Smith R, Doroshenk M, Wolf H, et al. Coverage of Colonoscopies under the Affordable Care Act's Prevention Benefit. The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Poudrier J, Mac-Lean RT. 'We've fallen into the cracks': Aboriginal women's experiences with breast cancer through photovoice. Nursing Inquiry. 2009;16:306–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regional Health Commission. Decade Review of Health Status for St. Louis City and County 2000–2010. St. Louis: St. Louis Regional Health Commission; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin AM, Jolly C. Visions and Voices: Indigent Persons Living With HIV in the Southern United States Use Photovoice to Create Knowledge, Develop Partnerships, and Take Action. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9:159–169. doi: 10.1177/1524839906293829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. London: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rose N. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149:627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB. All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community. New York: Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Steel CB, Rim SH, Joseph DA, Kind JB, Seeff LC. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening - United States, 2008–2010. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR Weekly) 2013;62:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, cA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TL, Owens OL, Friedman DB, Torres ME, Hebert JR. Written and spoken narratives about health and cancer decision making: a novel application of photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:833–840. doi: 10.1177/1524839912465749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera P, Gallin J, Schuk D, Davis N. "Trying to Eat Healthy": A Photovoice Study About Women's Access to Healthy Food in New York City. Affilia. 2009;24:300–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women's Health. Journal of Women's Health. 1999;8:185. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA, Ping XY. Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: a participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, McCaffery K, Nadel M, Atkin W. Socioeconomic differences in cancer screening participation: comparing cognitive and psychosocial explanations. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. Upscaling Downtown: Stalled Gentrification in Washington, D.C. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]