Summary

Toll Like Receptor 9 (TLR9), its adapter MyD88, the downstream transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) and type I interferons (IFN-I) are all required for resistance to infection with ectromelia virus (ECTV). However, it is not known how or in which cells these effectors function to promote survival. Here, we showed that after infection with ECTV, the TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 pathway was necessary in CD11c+ cells for the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes (iMo) to the draining lymph node (D-LN). In the D-LN, the major producers of IFN-I were infected iMo, which used the DNA sensor-adapter STING to activate IRF7 and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling to induce the expression of IFNα and IFNβ, respectively. Thus, in vivo, two pathways of DNA pathogen sensing act sequentially in two distinct cell types to orchestrate resistance to a viral disease.

Introduction

The ability of the innate immune system to sense infection is essential to mount innate and adaptive immune responses (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010; Wu and Chen, 2014). It is well established that pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to activate innate immune signaling pathways (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010). PAMPs are typically microbial nucleic acids and other macromolecules with repetitive structures common to pathogens, but not usually encountered in uninfected cells (Schenten and Medzhitov, 2011). PRR-initiated signaling cascades following virus infection culminate in the expression of Type I interferon (IFN-I), pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, that recruit and activate innate and adaptive immune cells (Wu and Chen, 2014).

PAMPs in the cell microenvironment are recognized by transmembrane PRRs that reside in the plasma and endosomal membranes, such as Toll like receptors (TLRs). For example, TLR9 recognizes double stranded DNA in endosomes (Ahmad-Nejad et al., 2002; Hemmi et al., 2000). PAMPs in the cytosol are sensed by cytosolic PRRs. For instance, RIG-I-Like Receptors (RLR) detect cytosolic viral RNA species (Goubau et al., 2013; Vabret and Blander, 2013), while DNA-dependent activator of IFN-regulatory factors (DAI), Interferon activated gene 204 (Ifi204, IFI16 in humans) and cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS, encode by M21d1) respond to cytosolic DNA (Wu and Chen, 2014).

To signal, PRRs use adapters. The adapters for TLRs are MyD88 and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing IFNβ (TRIF), for RLRs Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), and for DNA-sensing PRRs STING (Wu and Chen, 2014). Additional signaling steps downstream of these adapters link PRRs to the activation of several transcription factors, most frequently IRF3, IRF7, and NF-kB. These transcription factors induce the expression of IFN-I and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Wu and Chen, 2014).

Soon after breaching epithelia, many pathogenic viruses rapidly spread through afferent lymphatics to the regional draining lymph nodes (D-LN), from where they disseminate through efferent lymphatics to the bloodstream, ultimately reaching their target organs (Flint et al., 2009; Virgin, 2007). Ectromelia virus, an Orthopoxvirus (a genus of large DNA viruses), is the causative agent of mousepox, the mouse homologue of human smallpox (Esteban and Buller, 2005). Following infection through the skin of the footpad, ECTV spreads lympho-hematogenously to cause systemic disease. Indeed, ECTV was the virus used to describe this form of dissemination (Fenner, 1948) and is used as the textbook paradigm of lympho-hematogenous spread (Flint et al., 2009; Virgin, 2007).

During lympho-hematogenous dissemination, a swift anti-viral innate response in the D-LN can play a major role in restricting viral spread and deterring disease (Fang et al., 2008; Junt et al., 2007; Kastenmuller et al., 2012). It is therefore important to understand how different mechanisms of virus sensing contribute to this process. Here we dissect the contribution of PRRs to the antiviral response to ECTV in the D-LN. We show that the TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 axis is necessary in CD11c+ cells for the chemokine-driven recruitment of inflammatory monocytes (iMo) to the D-LN, but not directly essential for IFN-I production. Once iMo are infected, they use STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB pathways to respectively induce the expression of IFNα and IFNβ. Collectively, our work shows that the TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 and STING-IRF7 or STING-NFκB pathways have non-redundant, complementary and sequential roles in IFN-I expression in the D-LN and in resistance to a highly pathogenic viral disease.

RESULTS

TLR9-MyD88 and STING are critical for resistance to mousepox and the efficient induction of IFN-I in lymph nodes

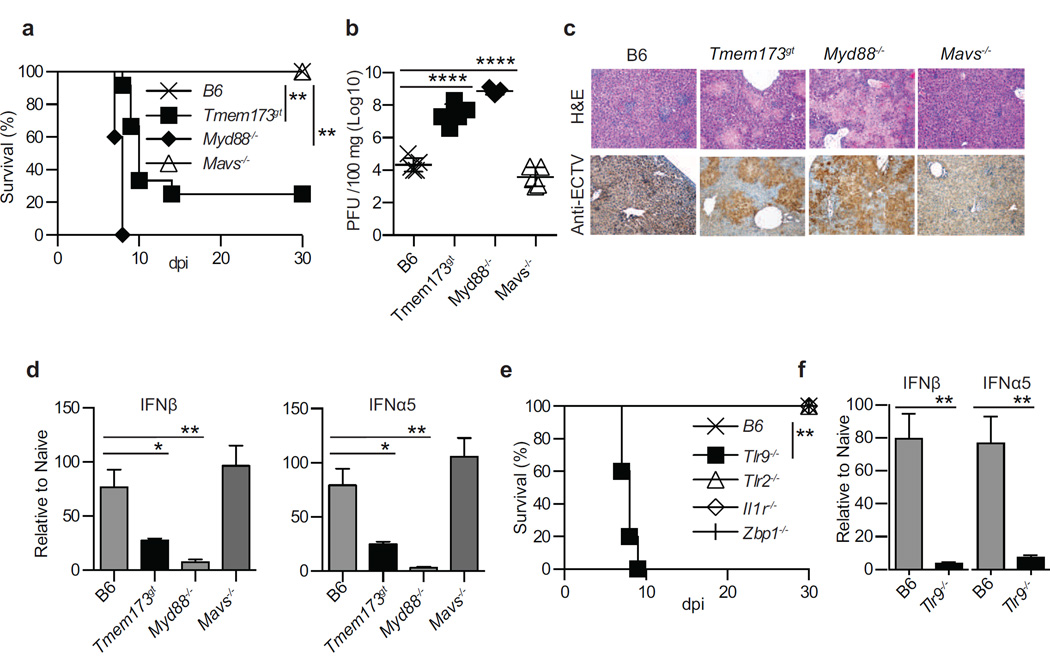

The TLR adapter MyD88 is required for the inherent resistance of B6 mice to mousepox (Rubio et al., 2013; Sutherland et al., 2011), while TRIF is not necessary (data not shown). We performed experiments to identify the specific role of MyD88, as well as of MAVS- and STING-driven pathways, in resistance to mousepox and IFN-I expression in vivo during acute ECTV infection. We found that after infection with ECTV in the footpad, mice deficient in MyD88 (Myd88−/−) or with inactive STING (Tmem173gt), but not those lacking MAVS (Mavs−/−), were susceptible to lethal mousepox (Figure 1a). Yet, death occurred in 100% of Myd88−/− but only in 80% Tmem173gt mice, a difference that was reproducible and highly significant (P=****) suggesting a more profound impairment in the absence of MyD88 than in the absence of STING signaling. Consistently, virus loads (Figure 1b) and pathology (Figure 1c) in the livers of Myd88−/− and Tmem173gt, but not of Mavs−/−, mice were significantly higher than in B6 mice. Notably, the virus titers were significantly lower (P<**) and the liver pathology was somewhat milder in Tmem173gt than in Myd88−/− mice. We next performed reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) on RNA obtained from the draining lymph node (D-LN) at 2.5 days post infection (dpi). We found that Myd88−/− and Tmem173gt but not Mavs−/− mice expressed significantly lower levels of “early” IFNβ and “late” IFNα5 than B6 mice. Yet, Myd88−/− mice expressed significantly lower levels of IFNβ (P=****) and IFNα5 (P=****) than Tmem173gt mice (Figure 1d). Thus, MyD88 and STING, but not MAVS, are both critical adapters for resistance to lethal ECTV infection and the efficient expression of IFN-I in the D-LN in vivo. However, mice are significantly more susceptible to mousepox with absent MyD88 than with deficient STING.

Figure 1. TLR9, MyD88 and STING are critical for resistance to mousepox and the efficient induction of IFN-I in lymph nodes.

Mice were infected with 3,000 pfu of ECTV in the footpad. a) Survival of the indicated mice. b) Virus loads in the livers of the indicated mice at 7 dpi as determined by plaque assay. c) Liver sections of the indicated mice at 7 dpi stained with H&E (top) or immunostained with anti-ECTV Ab (bottom). d) Expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi as determined by RT-qPCR. e) Survival of the indicated mice. f) Expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi as determined by RT-qPCR. Data are shown either as individual mice with mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or as mean ± SEM. Each panel displays data from one experiment with five mice per group and is representative of three similar experiments,. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

Next, we investigated several molecules upstream of MyD88 and STING that could be required for resistance to mousepox and/or IFN-I expression in the D-LN. As before, mice deficient in TLR9 (Tlr9−/−), but not in other TLRs, were susceptible to mousepox (Rubio et al., 2013; Samuelsson et al., 2008; Sutherland et al., 2011). In contrast, mice deficient in the IL-1 receptor (Il1r−/−), which also uses MyD88 as its adapter (Muzio et al., 1997), and mice deficient in the cytosolic DNA sensor DAI (Zbp1−/−) (Ishii et al., 2008), which is thought to signal through STING, were resistant (Figure 1e and not shown). Moreover, at 2.5 dpi, mice deficient in TLR9, but not in TLR2, IL-1R or DAI, expressed significantly lower IFN-I in the D-LN than B6 mice (Figure 1f and not shown). Thus, among those we tested, the only PRR upstream of MyD88 that is required for IFN-I expression in the D-LN during ECTV infection is TLR9. Further, DAI is not the critical sensor for STING.

IFN-I expression requires MyD88 and STING in bone marrow derived cells

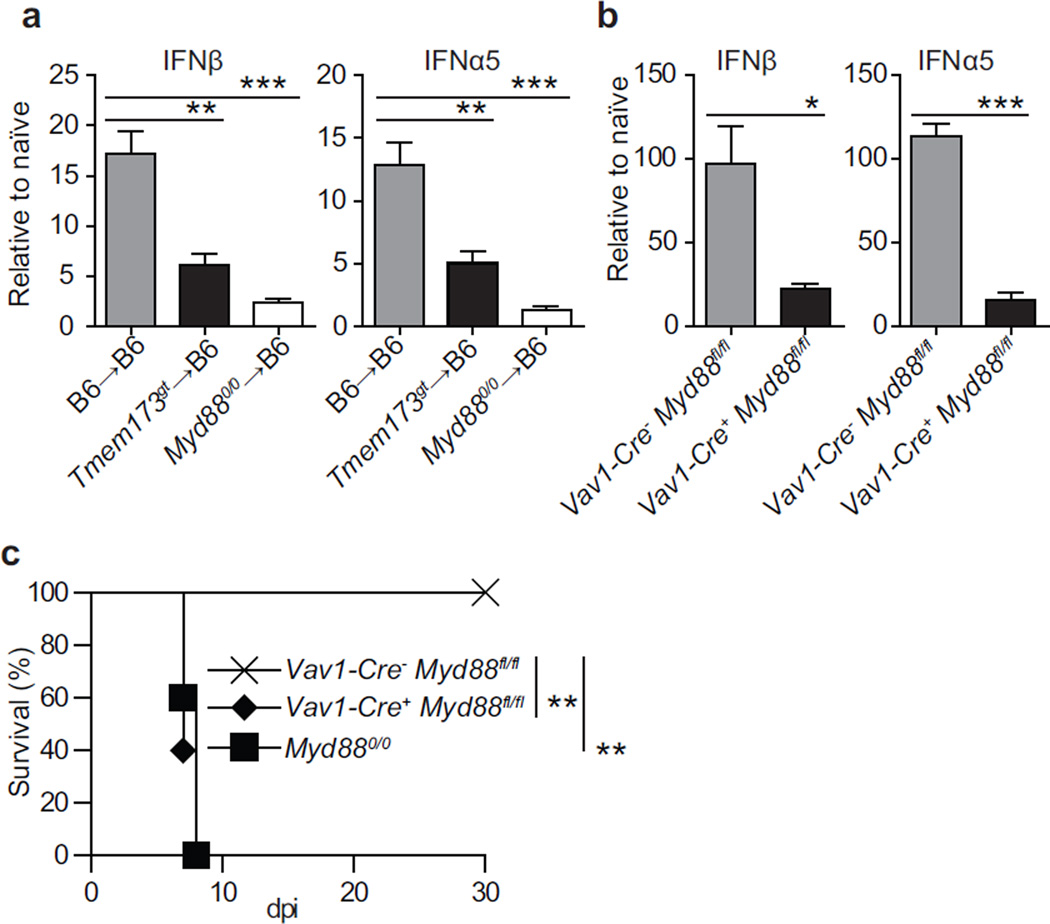

Next, we sought to identify the cells that produce IFN-I during infection. To distinguish the role of bone marrow-derived vs. parenchymal cells we used bone marrow chimeras. Expression of IFNβ and IFNα5 in the D-LNs at 2.5 dpi was significantly lower in Myd88−/−→B6 and Tmem173gt→B6 than in B6→B6 chimeras. Expression of IFNβ and IFNα5 was also significantly lower (P<* for IFNβ and P<** for IFNα5) in Myd88−/−→B6 than in Tmem173gt→B6 chimeras (Figure 2a). In another approach, Vav1-Cre+ Myd88fl/fl mice, which specifically lack MyD88 in hematopoietic cells, expressed significantly less IFN-I than Vav1-Cre− Myd88fl/fl controls (Figure 2b). Moreover, Vav1-Cre+ Myd88fl/fl but not Vav1-Cre− Myd88fl/fl mice succumbed to mousepox with similar kinetics to constitutive Myd88−/− mice (Figure 2c). Consequently, both MyD88 and STING in bone marrow-derived cells are essential for the efficient expression of IFN-I during ECTV infection in vivo. Moreover, MyD88 in hematopoietic cells is essential for resistance to mousepox.

Figure 2. IFN-I expression requires MyD88 and STING in bone marrow derived cells.

Mice were infected with 3000 pfu of ECTV in the footpad. a) Expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated bone marrow chimeras at 2.5 dpi. b) Expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi. P values are compared to Vav1-Cre-Myd88fl/fl. c) Survival of indicated mice. When applicable, data are shown as mean ± SEM. Each panel displays data from one experiment with five mice per group and is representative of three similar experiments except for a, which was performed twice. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

Infected inflammatory monocytes are responsible for most of the IFN-I expressed in the D-LN

In several infection models, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) sense infection through TLR9-MyD88 to become the major producers of IFN-I (Colonna et al., 2004; Ito et al., 2005). Yet, B6 mice depleted of pDC with the anti-BST2 mAb 927 (Blasius et al., 2006) (Figure S1a) did not differ significantly from mice treated with control rat IgG in terms of IFN-I expression in the D-LN at 2.5 dpi (Figure S1b), and virus loads in the liver at 7 dpi (Figure S1c). Consistent with these findings, they did not show any differences in IFN-I expression in the D-LN at 5 dpi, and were resistant to lethal mousepox (not shown). Hence, pDCs are neither the major producers of IFN-I in the D-LN nor essential for the resistance of B6 mice to mousepox following infection with ECTV.

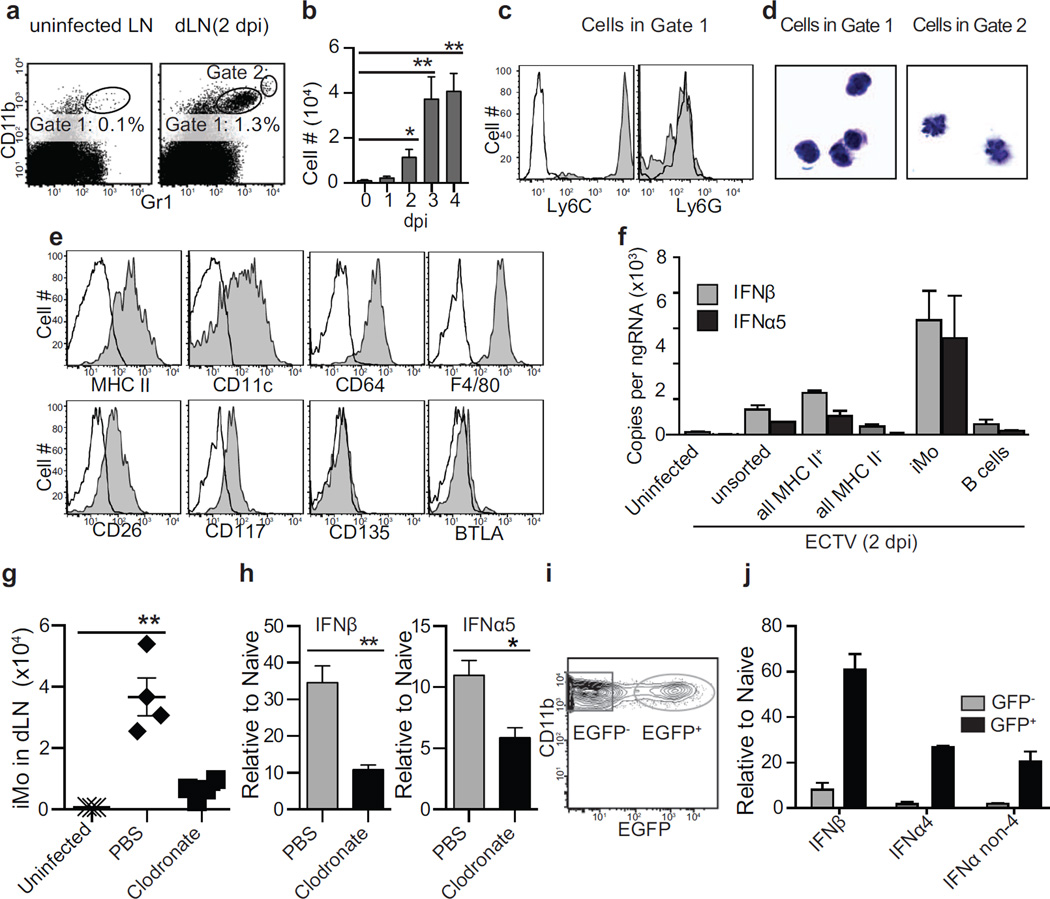

Having found that pDC are not the major producers of IFN-I in the D-LN, we set to identify the relevant bone-marrow derived cells. In initial experiments analyzing the response to ECTV in the D-LN at 2.5 dpi, we found an increase in CD11b+ cells that also stained with the anti-Ly6C+G mAb Gr1 (Figure 3a, Gate 1) but at lower levels than typical neutrophils (Figure 3a, Gate 2). The absolute number of Gate 1 cells peaked in the D-LN at 3 dpi (Figure 3b). At 5 dpi they had disappeared, most likely because at this time post-infection the D-LNs were almost acellular (not shown). The cells in Gate 1 stained with anti-Ly6C but not anti-Ly6G mAbs (Figure 3c) and were mononuclear (Figure 3d), indicating that they were not neutrophils. These cells were MHC II+ and CD11c+, and expressed the monocyte or macrophage markers CD64 and F4/80 (Gautier et al., 2012), but were negative or low for the DC core markers CD26, CD117 (c-Kit), CD135 (Flt3) and BTLA (Miller et al., 2012) (Figure 3e), suggesting that they were inflammatory monocytes (iMo) and not dendritic cells (DC). Hereafter, we will refer to the cells in Gate 1 as iMo.

Figure 3. Infected inflammatory monocytes are responsible for most of the IFN-I expressed in the D-LN.

a) Representative flow cytometry plots depicting the gating and frequency of a population of CD11b+ Gr1+ (Gate 1) cells in the popliteal LN of an uninfected mouse and in the D-LN of an infected mouse at 2.5 dpi with ECTV. A second gate (Gate 2) with higher expression of the molecules (presumably neutrophils) is also shown. b) Number of cells in Gate 1 at the indicated dpi. P values are compared to day 0. Data is displayed as the mean ± SEM of five mice per group in one experiment, which is representative of three similar experiments. c) At 2.5 dpi, Gate 1 cells were analyzed for expression of the indicated molecules using specific mAbs (shaded) or isotype Ab as control (open). Data, displayed as a representative sample of five mice per group. The experiment was repeated three times. d) At 2.5 dpi, Gate 1 (left) and Gate 2 (right) cells were sorted and stained with Giemsa. Data are representative of two experiments each with pools of 5 mice per group. e) As in c. Gate 1 cells are now referred as inflammatory monocytes (iMo). f) IFN-I expression in unsorted cells or the indicated sorted cells from uninfected LNs or D-LNs at 2.5 dpi. Data, displayed as mean ± SEM of pooled cells from five mice per group, are representative of 2 similar experiments. P values are not shown because the data correspond to two technical replicates. g) Number of iMo in the LNs of uninfected mice and at 2.5 dpi in the D-LN of mice treated intravenously with liposomes filled with PBS as a control or with clodronate to deplete monocytes and macrophages. Data, displayed as individual mice and mean ± SEM, correspond to an experiment with four mice per group, which is representative of two similar experiments. h) IFN-I expression at 2.5 dpi in the D-LN of mice receiving PBS- or clodronate -liposomes iv. Data, shown as mean ± SEM, correspond to an experiment with five mice per group, which is representative of two similar experiments. i) Representative flow cytometry plot depicting EGFP and CD11b expression in the iMo gate from the D-LN at 2.5 dpi with ECTV-EGFP. EGFP− (uninfected) and EGFP+ (infected). j) IFN-I expression in sorted EGFP− or EGFP+ iMo gated as in i. Data is displayed as mean ± SEM of pooled cells from five mice per group in one experiment, which is representative of two similar experiments. P values are not shown because the data correspond to two technical replicates. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01.

Using ECTV-EGFP (Fang et al., 2008) we found that in the D-LN, ECTV preferentially infected myeloid and B cells (Figure S2), which are mostly MHC II+. To identify the cell types that produce IFN-I in the D-LN, we determined IFN-I expression in sorted cell populations from the D-LN at 2.5 dpi. We found that IFN-I expression segregated with MHC II+ cells and, among these cells, iMo but not B cells expressed IFN-I (Figure 3f). We also sorted iMo, B cells and the rest of the cells in the D-LN of ECTV infected mice at 2.5 dpi. As compared to the rest of the cells, iMo expressed significantly higher levels of several innate immune genes involved in IFN-I expression including Tlr9, Myd88, M21d1 (which encodes cGAS) and Irf7 but not Tmem173, Irf3 and Nfkb1. On the other side, B cells only expressed significantly higher levels of Tlr9 and Irf3 (Figure S2). As compared to controls, significantly fewer iMo were recruited to the D-LN of mice that had been inoculated intravenously with liposomes filled with clodronate, known to deplete monocytes and macrophages in vivo (Seiler et al., 1997; Van Rooijen, 1989) (Figure 3g). Moreover, mice treated with clodronate-liposomes expressed significantly less IFN-I than those treated with PBS-liposomes (Figure 3h).

Next, we infected mice with ECTV-EGFP and sorted infected (EGFP+) and uninfected (EGFP−) iMo from D-LNs at 2.5 dpi (Figure 3i). We found that EGFP+ iMo expressed significantly more IFN-I than EGFP− iMo (Figure 3j). Thus, infected iMo are the major producers of IFN-I in the D-LN of mice infected with ECTV.

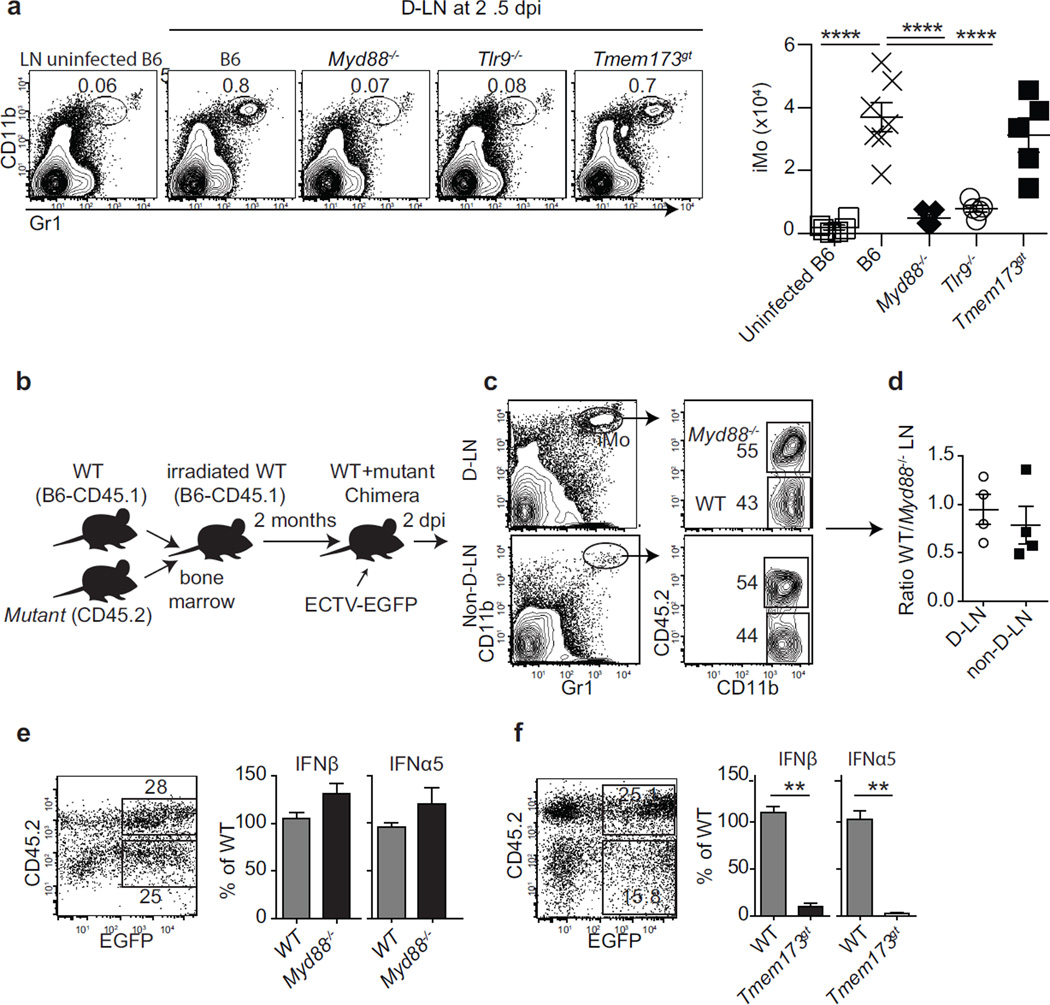

The recruitment of iMo needs extrinsic MyD88 while the efficient expression of IFN-I requires intrinsic STING

We next sought to identify the molecular mechanisms responsible for iMo recruitment. Compared to B6 mice, significantly fewer iMo were recruited into the D-LN of Tlr9−/− and Myd88−/− but not Tmem173gt mice (Figure 4a). Hence, the recruitment of iMo into the D-LN requires TLR9-MyD88 but not STING. We next asked whether iMo require intrinsic and/or extrinsic MyD88 to accumulate in the D-LN and/or express IFN-I. For this, we used mixed bone marrow chimeras made with a 1:1 mixture of bone marrow from B6 congenic CD45.1+ (WT) and CD45.2+ Myd88−/− bone marrow transferred into WT (henceforth, WT+Myd88−/− chimeras; Figure 4b). At 2.5 dpi, WT and Myd88−/− iMo accumulated in the D-LN of WT+Myd88−/− chimeras at similar frequencies (Figure 4c–d). Of note, in WT+Myd88−/− chimeras infected with ECTV-EGFP, EGFP+ Myd88−/− and EGFP+ WT iMo expressed similar levels of IFN-I (Figure 4e). Conversely, in WT+Tmem173gt chimeras, EGFP+ Tmem173gt iMo expressed significantly less IFN-I than EGFP+ WT iMo (Figure 4f). Hence, to accumulate in the D-LN or produce IFN-I iMo do not require intrinsic MyD88. However, they need intrinsic functional STING to efficiently express IFN-I.

Figure 4. The recruitment of iMo needs extrinsic MyD88 while the efficient expression of IFN-I requires intrinsic STING.

a) The indicated mice were infected with ECTV and at 2.5 dpi, their D-LN were analyzed for the presence of iMo. Representative flow cytometry plots (left) and the calculated numbers of iMo (right) are shown. Data, shown as individual mice and mean ± SEM, correspond to an experiment with five mice per group, which is representative of two similar experiments. b) Diagram of the experiments in c–f. c) Representative flow cytometry plots of the D-LN and non-D-LN of WT+Myd88−/− chimeras at 2.5 dpi. The plots on the left show CD11b and Gr1 staining with the iMo gates marked. The plots on the right show the expression of CD45.2 and CD11c in the iMo gates. The gates for mutant (CD45.2+) and WT (CD45.2−) iMo are shown. d) Ratio of WT/Myd88−/− iMo in the D-LN of WT+Myd88−/− chimeras. Data, shown as individual mice and mean ± SEM, correspond to an experiment with four mice per group, which is representative of two similar experiments. e) Representative flow cytometry plot for EGFP and CD45.2 expression in gated iMo from D-LNs of WT+Myd88−/− chimeras at 2.5 dpi with ECTV-EGFP (left) and IFN-I expression in the sorted EGFP+ WT and EGFP+ Myd88−/− iMo (right). Data are for pooled cells from five mice per group and representative of two similar experiments. Means ± SEM of three technical replicates are shown. f) As in e but with cells from WT+Tmem173gt chimeras. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

The accumulation of iMo in the D-LN requires TLR9 and MyD88 expression in chemokine-producing CD11c+ cells

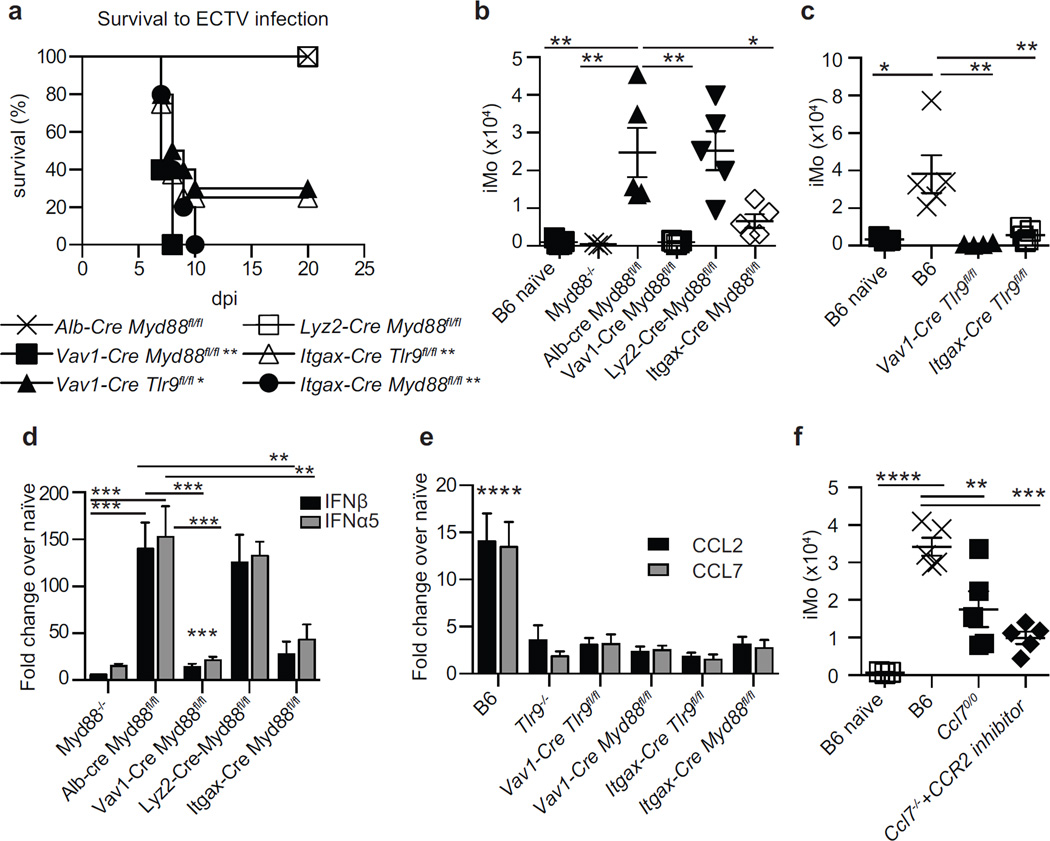

Next, we crossed mice carrying Cre recombinase in different cell types with mice carrying floxed alleles of Myd88 (Myd88fl/fl) or Tlr9 (Tlr9fl/fl) to specifically eliminate MyD88 and TLR9 in cells of interest. Mice without Myd88 in hepatocytes (Alb-Cre Myd88fl/fl, selected as controls because hepatocytes are late targets of ECTV infection), or in monocytes and macrophages (Lyz2-Cre Myd88fl/fl) survived the infection. Conversely, most Vav1-Cre Tlr9fl/fl mice and all Vav1-Cre Myd88fl/fl mice, which are respectively deficient in TLR9 and Myd88 in all hematopoietic cells, succumbed to mousepox. Similarly, most Itgax-Cre Tlr9fl/fl and all Itgax-Cre Myd88fl/fl, which respectively lack TLR9 and MyD88 in CD11c+ cells, also died from mousepox (Figure 5a). Concordantly, iMo accumulated efficiently in the D-LN of Alb-Cre Myd88fl/fl and Lyz2-Cre Myd88fl/f but poorly in the D-LN Vav1-Cre Myd88fl/fl, Itgax-Cre Myd88fl/fl, Vav1-Cre Tlr9fl/fl and Itgax-Cre Tlr9fl/fl mice (Figure 5b and c). Moreover, Vav1-Cre Myd88fl/fl and Itgax-Cre Myd88fl/fl mice expressed significantly lower levels of IFN-I in the D-LN than Alb-Cre Myd88fl/fl, while normal levels were detected in Lyz2-Cre Myd88fl/fl mice (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. The accumulation of iMo in the D-LN requires TLR9 and MyD88 in chemokine-producing CD11c+ cells.

a) Survival of the indicated mice to ECTV infection. Data correspond to one experiment with five mice per group and is representative of three similar experiments. P values are compared to Alb-Cre Myd88fl/fl mice. b) Calculated number of iMo in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi. Data, displayed as individual mice with mean ± SEM, correspond to one experiment with five mice per group, which is representative of three similar experiments. c) As in b. d) Expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi. P values are compared to Alb-Cre Myd88fl/fl mice. Data, displayed as mean ± SEM, correspond to one experiment with five mice per group, which is representative of three similar experiments. e) Ccl2 and Ccl7 expression in the D-LN at 1 dpi. P values are compared to naive B6 mice (not shown) and are similar for Ccl2 and Ccl7. Data displayed as in e. f) As in b. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

We next sought to understand why extrinsic TLR9 and MyD88 are required to recruit iMo to the D-LN. Because chemokine gradients regulate leukocyte migration (Griffith et al., 2014), we used RT-qPCR to determine which chemokines were upregulated in the D-LN at 1 dpi in a TLR9 and MyD88 dependent manner. We found that CCL2 and CCL7 (Figure 5e), which are ligands for the chemokine receptor CCR2 and known to be involved in the recruitment of iMo to inflamed tissues (Griffith et al., 2014), were upregulated in B6 but not in Tlr9−/−, Vav1-cre+ Myd88fl/fl, Itgax-cre+ Myd88fl/fl, Vav1-cre+ Tlr9fl/fl and Itgax-cre+ Tlr9fl/fl mice. This suggested that CCL2 and CCL7, induced by TLR9 and MyD88 signaling, might be involved in the recruitment of iMo to the D-LN. In agreement, mice deficient in CCL7 (Ccl7−/−) recruited significantly fewer iMo to the D-LN than B6 mice upon ECTV infection. The impaired recruitment of iMo in Ccl7−/− mice was exacerbated by treatment with the CCR2 antagonist RS102895 (Giunti et al., 2006) (Figure 5f). These data suggest that the efficient recruitment of iMo to the D-LN requires expression of CCR2-binding chemokines and that this expression requires intrinsic TLR9 and MyD88 in CD11c+ cells. Of note, iMo were still the key cells that expressed IFN-I in RS102895-treated Ccl7−/− mice (Figure S3a). Yet, despite the reduced number of iMo, we did not detect significant differences in the levels of IFN-I in the D-LN of B6 and RS102895 treated Ccl7−/− mice (not shown). While we do not know the reason for the lack of significant differences, we have found that RS102895-treated Ccl7−/− mice have significantly higher virus loads than B6 mice in the D-LN at 2.5 dpi and iMo are still the major producers of IFN-I (Figure S3b). Perhaps this increase in virus loads somehow compensates the decrease in iMo.

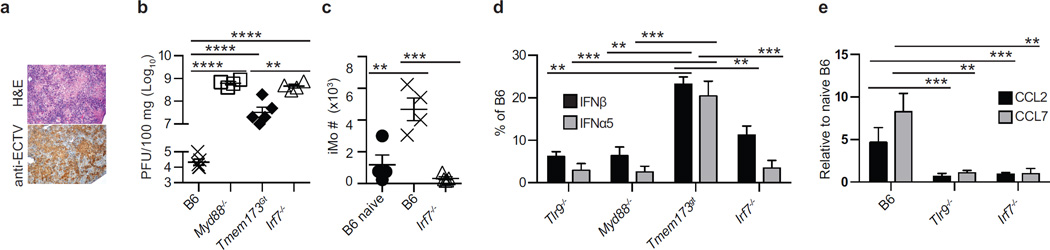

IRF7 is required for the efficient recruitment of iMo and IFN-I expression in the D-LN

Next, we sought to identify the transcription factors downstream of TLR9-MyD88 and STING necessary for the accumulation of iMo in the D-LN and for their expression of IFN-I. It is well established that TLR9-MyD88 signaling activates the transcription factors IRF7 and NFκB (Orzalli and Knipe, 2014), while STING mainly activates IRF3 and NFκB (Wu and Chen, 2014) but can also activate IRF7 (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). As we previously reported, B6 mice that lack the transcription factor IRF7 (Irf7−/−) are susceptible to mousepox while B6 mice that lack IRF3 (Irf3−/−) are resistant (Rubio et al., 2013). Similar to Myd88−/− mice, Irf7−/− mice were more susceptible to ECTV infection than STING deficient mice because 100% of Irf7−/− and Myd88−/− but only 80% of Tmem173gt mice succumbed to mousepox (not shown). Also, the livers of Irf7−/− mice showed severe pathology as determined by histology and immunohistochemistry (Figure 6a). Accordingly, the virus titers in the livers of Irf7−/− mice were as high as those in Myd88−/− (Figure 6b). Consistent with being downstream of MyD88, the virus titers in Irf7−/− mice were similar to those in Myd88−/− mice but significantly higher than in Tmem173gt mice (P<**). Also phenocopying MyD88 deficiency, the recruitment of iMo to the D-LN of Irf7−/− mice was impaired (Figure 6c). Furthermore, the expression of IFN-I in the D-LN of Irf7−/− mice was as low as in the D-LN of Myd88−/− mice and significantly lower than in the D-LN of Tmem173gt mice (Figure 6d). In addition, Irf7−/− mice did not upregulate the expression of Ccl2 and Ccl7 in the D-LN (Figure 6e). Together, these data suggest that the expression of the chemokines that recruit iMo to the D-LN requires the transcription factor IRF7 downstream of TLR9-MyD88.

Figure 6. IRF7 is required for the efficient recruitment of iMo and IFN-I expression in the D-LN.

a) Representative liver sections from Irf7−/− mice at 7 dpi stained with H&E (top) or with anti-ECTV Ab (bottom). The experiment was performed three times with four or five mice per group with similar results. b) ECTV titers in the liver of the indicated mice at 7 dpi. Data, displayed as individual mice with mean ± SEM, correspond to one experiment with four or five mice per group, which is representative of three similar experiments. c) Numbers of iMo in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi. Data as in b, d) IFN-I in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi expressed as percent of the values for the same interferon in infected B6 mice. Data, displayed as mean ± SEM, correspond to one experiment with five mice per group, which is representative of three similar experiments. e) Expression of the indicated chemokines in the D-LN of the indicated mice at 1 dpi. Data as in d. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

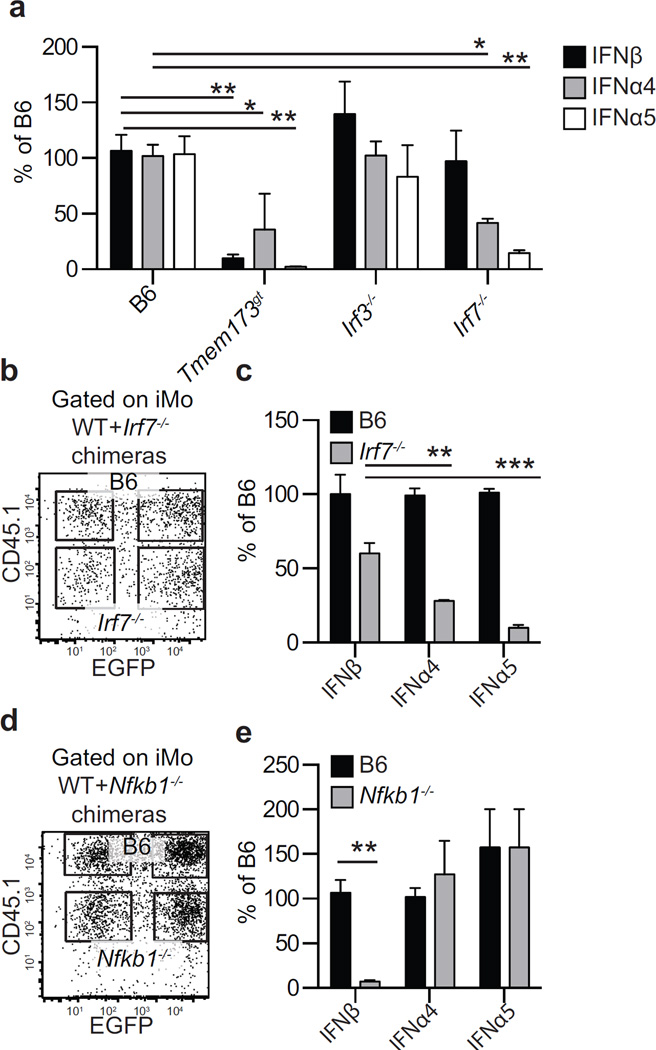

Inflammatory monocytes require intrinsic STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB to respectively express IFNα and IFNβ

We next determined whether iMo require intrinsic IRF7 to express IFNα and IFNβ. We found that infected iMo obtained at 2.5 dpi with ECTV-EGFP from the D-LNs of Tmem173gt mice expressed IFNβ inefficiently, while those from Irf3−/− and Irf7−/− mice expressed as much IFNβ as iMo from WT B6 mice. In contrast, infected iMo from the D-LN of Irf3−/− mice expressed as much “early” IFNα4 and “late” IFNα5 as those from WT mice, but those from Tmem173gt and the few present in Irf7−/− mice expressed significantly less (Figure 7a). Therefore, the signaling pathways for IFNα and IFNβ expression diverge downstream of STING, with IRF7 being required for efficient IFNα but not IFNβ expression.

Figure 7. Inflammatory monocytes require intrinsic STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB to respectively express IFNα and IFNβ.

a) Expression of IFN-I in sorted EGFP+ iMo sorted from the D-LN of the indicated mice at 2.5 dpi. Data, displayed as mean ± SEM from one experiment representative of three, correspond to pooled cells from five mice per group and three technical replicates. b) Representative flow cytometry plots of gated iMo from the D-LN at 2.5 dpi of WT+ Irf7−/− chimeras showing CD45.1 and EGFP expression (left). c) IFN-I expression in sorted infected (EGFP+) WT (CD45.1+) and Irf7−/− (CD45.1−) iMo from WT+Irf7−/− chimeras as identified in b. Data, displayed as mean ± SEM from one experiment representative of three, correspond to pooled cells from five mice per group and three technical replicates. d) as in b but for WT+Nfkb1−/− chimeras. e) As in c but for WT+Nfkb1−/− chimeras. For all, * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001.

Given our previous finding of a crosstalk between the NFκB and IFN-I pathways during ECTV infection (Rubio et al., 2013), we speculated that in ECTV infected iMo, NFκB is the transcription factor downstream of STING that is responsible for the expression of IFNβ. However, we were unable to directly test this idea in Nfkb1−/− mice, as these mice lack popliteal lymph nodes (Rubio et al., 2013). Thus, we produced WT+Nfkb1−/− and also WT+Irf7−/− bone marrow chimeras (Figure 7b–e). In both types of chimeras, WT and mutant iMo accumulated in the D-LN at similar frequencies (not shown). Hence, iMo do not need intrinsic NFκB or IRF7 to accumulate in the D-LN. When tested for IFN-I expression, Irf7−/− iMo expressed significantly less “early” IFNα4 and “late” IFNα5 than WT iMo but the levels of “early” IFNβ were similar. On the other hand, Nfkb1−/− iMo expressed as much “early” and “late” IFNα but significantly less IFNβ than WT iMo. Thus, in ECTV infected iMo, efficient transcription of “early” and “late” IFNα requires IRF7 while the expression of IFNβ is mostly dependent on NFκB transcription.

Discussion

We have studied how different pathways of pathogen sensing and cell types contribute to IFN-I expression and resistance to a highly lethal infection caused by ECTV, a DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus that also includes variola virus (VARV, the virus that causes smallpox) and vaccinia virus (VACV, the smallpox vaccine). For this purpose, we have focused on the D-LN because of its critical role in restricting viral spread (Fang et al., 2008; Junt et al., 2007; Kastenmuller et al., 2012).

The most important aspect of our work is the finding that the DNA-sensing pathways TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 and STING-IRF7-NFκB are essential for efficient T-IFN production and resistance to mousepox but that their respective roles in IFN-I expression are very different: the TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 pathway is required in CD11c+ cells for the expression in the D-LN of CCR2 ligands -and likely other pro-inflammatory molecules necessary for the efficient recruitment of iMo to the D-LN- while the STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB axes are needed for IFN-I expression in infected iMo. That STING is necessary for IFN-I expression is consistent with the recent finding that STING is required for IFN-I expression in mouse cDC infected with modified VACV strain Ankara (MVA) (Dai et al., 2014). While we have ruled out DAI as the critical DNA sensor, we have not yet identified which is the receptor upstream of STING that senses ECTV to drive IFN-I expression. We hypothesize the key sensor is cGAS, because cGAS-STING is used by mouse cDC (Dai et al., 2014; Li et al., 2013), mouse macrophages and fibroblasts (Li et al., 2013), and human embryonic kidney 293 cells (Ablasser et al., 2013) to produce IFN-I in vitro following infection with WT VACV or MVA.

We have also ruled out TRIF and MAVS as key players in IFN-I expression and resistance to mousepox after ECTV infection. That TRIF is not essential is not surprising because TLR9 uses MyD88 but not TRIF as the adapter, and because TLR9 is the only TLR required for resistance to mousepox (Rubio et al., 2013; Samuelsson et al., 2008; Sutherland et al., 2011). However, the finding that MAVS has no role is unexpected, because MAVS transduces signals from RNA-sensing RLRs, and it has been shown that in cultured cells, VACV, which is very similar to ECTV, produces RNA species that can activate these pathways and induce IFN-I expression (Myskiw et al., 2011; Pichlmair et al., 2009).

We also found that pDC are not required for IFN-I expression or survival to ECTV infection. pDC, which express RNA- and DNA-sensing TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 have been touted as professional IFN-I producers (Gilliet et al., 2008). Yet, they have been proven not essential for IFN-I expression and/or resistance to infection in various infectious mouse models including vesicular stomatitis virus, influenza virus, mouse cytomegalovirus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (Reizis et al., 2011). Furthermore, it has been shown that pDC contribute to IFN-I expression to systemic but not local infection with HSV-1, another large DNA virus (Swiecki et al., 2013). That pDC are not essential for resistance to ECTV is in contrast to the findings of Tahiliani and collagues, who recently reported that mice depleted of pDC succumbed to mousepox (Tahiliani et al., 2013). Although that study did not examine IFN-I expression post-infection, we attribute this discrepancy to differences in anti-BST2 mAb clones and doses between our study and theirs and the possible depletion of other cell types by this type of mAbs (Swiecki and Colonna, 2010).

The finding that the cells that exclusively express IFN-I in the D-LN are infected iMo is novel and unexpected because these cells are not considered professional IFN-I producers. Yet, it has been shown that Ly6C+ iMo use TLR2 to produce IFN-I during VACV infection (Barbalat et al., 2009) and that iMo produce IFNβ in response to Toxoplasma gondii (Han et al., 2014). Moreover, other myeloid cells have been found to produce IFN-I. For example, conventional DC (cDC) produce IFN-I in response to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (Diebold et al., 2003), reovirus (Johansson et al., 2007) and rotavirus (Lopez-Guerrero et al., 2010) in vivo. Also, cDC and macrophages express IFN-I in response to Herpes simplex virus (Rasmussen et al., 2007) and alveolar macrophages in response to Newcastle disease virus (Kumagai et al., 2007). In culture, influenza virus-infected human monocyte-derived DC also produce IFN-I (Cao et al., 2012).

The discoveries that iMo express IFN-I only if they are infected and that STING is the critical adapter are internally consistent. STING is used by PRRs that recognize the presence of PAMPs in the cytosol, which indicates an ongoing infection. Interestingly, while B cells constitute the vast majority of infected cells in the D-LN, they failed to express IFN-I. A possible reason is that when compared to monocytes, they express low levels of IRF7 and the cytosolic DNA sensors IFI16 (Ifi204) and cGAS (E330016A19Rik) as indicated in the Immgen database (www.immgen.org) and as suggested by our own RT-qPCR analysis.

The identity and residence of the CD11c+ cells in which the TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 pathway is needed for CCR2-ligand expression still needs to be elucidated. One possibility is that they are Langerhans cells or dermal DCs that reside in the footpad and migrate to the D-LN in a TLR9-MyD88 dependent manner (Martin-Fontecha et al., 2009). It is also possible that these cells are DC that reside in the subcapsular space and that have recently shown to be the first to capture particulate antigens in the D-LN (Radtke et al., 2015). We speculate that CD11c+ cells need TLR9-MyD88 intrinsically to express the CCR2 ligands and likely other inflammatory cytokines that are required for iMo migration. However, It remains possible that the role of TLR9-MyD88 in CD11c+ cells is also indirect for this function. Regardless of this, iMo migrate to the D-LN in response to signals that depend on TLR9-MyD88 in CD11c+ cells. After migrating to the D-LN, iMo become targets of infection and, consequently, the major producers of IFN-I in the D-LN. Notably, iMo do not need intrinsic MyD88 to migrate to the D-LN or to produce IFN-I; instead, they rely on intrinsic STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB signaling for expression of IFNα and IFNβ, respectively.

The most frequently-studied IRF downstream of STING is IRF3 (Wu and Chen, 2014). Hence, it may be surprising that the expression of IFN-I is not altered in Irf3−/− mice. However, it has been shown that STING can directly activate IRF7 (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). Moreover, IRF7 is expressed at much higher levels than IRF3 in most myeloid cells (www.immgen.org) and in our own experiments, IRF7 but not IRF3 was expressed at higher levels in iMo than in other cells. This suggests that in iMo, STING-IRF7 signaling makes IRF3 redundant.

Our experiments suggest that iMo have additional pathways for IFN-I expression because infected iMo deficient in Irf7−/− and Tmem173gt expressed detectable (albeit significantly reduced) IFN-I. While insufficient to protect most mice from lethal mousepox, these alternate pathways may explain why Tmem173gt mice, which recruit iMo to the D-LN, are less susceptible than MyD88 and IRF7 mice, which do not recruit iMo to the D-LN.

We also found that the expression of IFNβ in iMo is strictly dependent on NFκB, even though the ifnb1 enhancer has binding sites for both NFκB, IRF3 and IRF7 (Honda et al., 2005). Thanos and colleagues have shown that NFκB p65 is needed for the initial capture and stabilization of CBP-p300 at the enhanceosome (Merika et al., 1998), likely this role for NFκB is more critical in driving IFNβ expression in iMo than it is in MEFs, where NFκB appears largely dispensable for virus-driven IFNβ expression (Balachandran and Beg, 2011; Wang et al., 2007).

In summary, we have identified iMo as the cell type critical for IFN-I production in the D-LN following infection with a poxvirus through its biological route in its natural host. Moreover, we show that two DNA-sensing pathways, both traditionally associated with a direct role in IFN-I expression, play distinct but sequentially roles in different cell types: The TLR9-MyD88-IRF7 pathway functions in CD11c+ cells to recruit iMo to the D-LN while the STING-IRF7 and STING-NFκB pathways are directly responsible for IFN-I production following iMo infection. Together, these results provide important insights into how distinct pathogen sensing mechanisms co-operate to recognize and limit pathogen spread in vivo

Experimental Procedures

Mice and animal experiments

All the procedures involving mice were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All protocols were approved by Fox Chase Cancer Center’s (FCCC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. B6 (C57BL/6, CD45.2+, Taconic) and B6-LY5.1/Cr (B6-CD45.1, CD45.1+ NCI-Charles River) mice were purchased at 6–8 weeks of age. All other mice, in a B6 background, were bred at FCCC from original breeders obtained from different sources and used at an age of 6–16 weeks. Vav1-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Vav1-cre)A2Kio/J), Alb-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Alb-cre)21Man/J), Lyz2-Cre (B6.129P2-Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo/J), Itgax-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1-1Reiz/J), Ccl7−/− (B6.129S4-Ccl7tm1ifc/J), Nfkb1−/− (B6.Cg-Nfkb1tm1Bal/J), Myd88fl/fl (B6.129P2(SJL)-Myd88tm1Defr/J), Tmem173gt (C57BL/6J-Tmem173gt/J), Tlr2−/− (B6.129-Tlr2tm1Kir/J), Il1r−/− (B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J) mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratories. B6.129-Tlr9tm1Aki/Obs (Tlr9−/−) and B6.129-Myd88tm1Aki/Obs (Myd88−/−) mice were produced by Dr. S. Akira (Osaka University, Japan) (Adachi et al., 1998; Hemmi et al., 2000) and generously provided by Dr. Robert Finberg (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA). Irf7−/− (B6.129P2-Irf7tm1Ttg/TtgRbrc) and Irf3−/− (B6;129S6-Irf3tm1Ttg/TtgRbrc) and B6.129B6-Mavstm1Tsse were from Riken Bioresource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). Ifnar1−/− mice backcrossed to B6 (Moltedo et al., 2011) were a gift from Dr. Thomas Moran (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY), Zbp1−/− mice (Ishii et al., 2008) were a gift from Dr. S. Akira. Tlr9fl/fl mice were produced in the Shlomchik laboratory and will be described in detail elsewhere. Briefly, LoxP sites were inserted flanking exon 2, which contains virtually all of the protein coding sequences, of TLR9. The mutant allele was created in B6x129 ES cells (line BA1) and proper targeting was confirmed by PCR, Southern blotting, and sequencing. Subsequent to germline transmission the floxed NeoR gene that was part of the original construct was deleted by breeding to a mouse line that expressed Cre-recombinase and the proper deletion again confirmed by Southern blot. The resulting mice were bred to B6 mice for 10 generation before crossing with the Cre-deleter mice obtained from Jackson.

Production of bone marrow chimeric mice

Bone marrow chimeras were prepared as previously described (Sigal et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2010) using 5–7 weeks old mice as donors and recipients. For mixed bone marrow chimeras, bone marrow cells from the two donor types were mixed at 1:1 ratio. Chimeras were used in experiments six to eight weeks after reconstitution.

Viruses and infection

Virus stocks, including ECTV Moscow strain (ATCC VR-1374) and ECTV-EGFP (Fang et al., 2008), were propagated in tissue culture as previously described (Xu et al., 2008). Mice were infected in the footpad with 3000 plaque forming units (pfu) ECTV WT or ECTV-EGFP as indicated. For the determination of survival, the mice were monitored daily. To avoid unnecessary suffering, mice were euthanized and counted as dead when imminent death was certain as determined by lack of activity and unresponsiveness to touch. For virus titers, the entire spleen or portions of the liver were homogenized in PBS using a Tissue Lyser (Qiagen). Virus titers were determined on BS-C-1 cells as before (Xu et al., 2008).

Cell depletions

To deplete pDCs, B6 mice were injected with 500 ug rat mAb 927 or control rat IgG (Blasius et al., 2006) one day before and one day after infection with ECTV. Efficient depletion of pDC was confirmed by flow cytometry using mAbs B220 and 400c (anti-Siglec-H) on inguinal LNs and spleen at 2 days after the second depletion. To deplete monocytes/macrophages, mice received 200 µl clodronate-liposomes diluted to 5mg/ml clodronate or control PBS-liposomes intravenously 2 days before infection.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described (Xu et al., 2008). mAbs to CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (GK1.5) and CD8a (53–6.7), CD11c (N418), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), CD64 (X54-5/7.1), F4/80 (BM8), CD135 (Flt3, clone A2F10), CD117 (c-Kit, clone 2B8), CD272 (6A6), CD26 (H194-112), IA/IE (M5/114.15.2), Ly-6G (IA8), Ly-6C(HK1.4), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD317 (BST2, PDCA-1, Clone 927) and CXCL9 (MIG-2F5.5) were from Biolegend. mAbs to CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), Ly-6G and Ly-6C (Gr-1, Clone RB6-8C5), B220 (RA3-6B2) and CD11b (H194-112) were from BD Biosciences. mAb to Siglec-H (eBio440c) was from eBioscience.

To obtain single-cell suspensions, LNs were minced and dissociated in Liberase TM (1.67 Wünsch units/ml) and DNase I (0.2 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics) in PBS with 25mM of Hepes for 30 min at 37°C. Liberase digestion was followed by mechanical disruption of the tissue through a 70-µm filter. Cells were washed once with complete RPMI medium before surface staining. For analysis, samples were acquired using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar). For cell sorting, samples were acquired using a BD FACSAria™ III sorter (BD Biosciences).

Histopathology

Livers were harvested and fixed with formalin and stained with H&E or with rabbit anti-EVM135 as previously (Xu et al., 2012). Sorted cells were stained using a standard Wright-Giemsa protocol.

RNA preparation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA from LNs was obtained with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as previously (Rubio et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2012). Total RNA from sorted cells (104–105 cells) was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ~104 cells were added into 1 ml of Trizol. When precipitating RNA, 10 ug of RNase-free glycogen (Invitrogen) was added to the aqueous phase as a carrier. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Lift Technologies). qPCR was performed as before (Rubio et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2012) using probes from the Universal Library (Roche) and the oligonucleotides suggested by the manufacturer’s software.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). For survival we used the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox). For other experiments, ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons or student’s t-test were used as applicable. In all figures * = p<0.05; ** = p<0.01; *** = p<0.001; **** p=0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Holly Gillin for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript and Dr. Siddharth Balachandran for critical reading. We also thank the Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) Laboratory Animal, Flow Cytometry and Tissue Culture Facilities for their services. This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI065544, R01AI110457 and U19AI083008 to L.J.S. and P30CA006927 to the FCCC. S.R. was supported by T32 CA-009035036 to FCCC. A generous gift form the Kirby Foundation also contributed to fund this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ablasser A, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hemmerling I, Horvath GL, Schmidt T, Latz E, Hornung V. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature. 2013;503:530–534. doi: 10.1038/nature12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad-Nejad P, Hacker H, Rutz M, Bauer S, Vabulas RM, Wagner H. Bacterial CpG-DNA and lipopolysaccharides activate Toll-like receptors at distinct cellular compartments. European journal of immunology. 2002;32:1958–1968. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<1958::AID-IMMU1958>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S, Beg AA. Defining emerging roles for NF-kappaB in antivirus responses: revisiting the interferon-beta enhanceosome paradigm. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002165. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbalat R, Lau L, Locksley RM, Barton GM. Toll-like receptor 2 on inflammatory monocytes induces type I interferon in response to viral but not bacterial ligands. Nature immunology. 2009;10:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/ni.1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasius AL, Giurisato E, Cella M, Schreiber RD, Shaw AS, Colonna M. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 is a specific marker of type I IFN-producing cells in the naive mouse, but a promiscuous cell surface antigen following IFN stimulation. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:3260–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Taylor AK, Biber RE, Davis WG, Kim JH, Reber AJ, Chirkova T, De La Cruz JA, Pandey A, Ranjan P, et al. Rapid differentiation of monocytes into type I IFN-producing myeloid dendritic cells as an antiviral strategy against influenza virus infection. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:2257–2265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nature immunology. 2004;5:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P, Wang W, Cao H, Avogadri F, Dai L, Drexler I, Joyce JA, Li XD, Chen Z, Merghoub T, et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara triggers type I IFN production in murine conventional dendritic cells via a cGAS/STING-mediated cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1003989. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold SS, Montoya M, Unger H, Alexopoulou L, Roy P, Haswell LE, Al-Shamkhani A, Flavell R, Borrow P, Reis e Sousa C. Viral infection switches non-plasmacytoid dendritic cells into high interferon producers. Nature. 2003;424:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nature01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban DJ, Buller RM. Ectromelia virus: the causative agent of mousepox. The Journal of general virology. 2005;86:2645–2659. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M, Lanier LL, Sigal LJ. A role for NKG2D in NK cell-mediated resistance to poxvirus disease. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner F. The pathogenesis of the acute exanthems; an interpretation based on experimental investigations with mousepox; infectious ectromelia of mice. Lancet. 1948;2:915–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(48)91599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint SJ, Enquist LW, Racanniello VR, Skalka AM. Principles of virology. 3rd edn. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, Chow A, Elpek KG, Gordonov S, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nature immunology. 2012;13:1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliet M, Cao W, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: sensing nucleic acids in viral infection and autoimmune diseases. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8:594–606. doi: 10.1038/nri2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunti S, Pinach S, Arnaldi L, Viberti G, Perin PC, Camussi G, Gruden G. The MCP-1/CCR2 system has direct proinflammatory effects in human mesangial cells. Kidney international. 2006;69:856–863. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity. 2013;38:855–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2014;32:659–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SJ, Melichar HJ, Coombes JL, Chan SW, Koshy AA, Boothroyd JC, Barton GM, Robey EA. Internalization and TLR-dependent type I interferon production by monocytes in response to Toxoplasma gondii. Immunology and cell biology. 2014;92:872–881. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Yanai H, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Regulation of the type I IFN induction: a current view. International immunology. 2005;17:1367–1378. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ, Kawagoe T, Koyama S, Matsui K, Kumar H, Kawai T, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O, Takeshita F, Coban C, et al. TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature. 2008;451:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature06537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Wang YH, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer seminars in immunopathology. 2005;26:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science. 2010;327:291–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C, Wetzel JD, He J, Mikacenic C, Dermody TS, Kelsall BL. Type I interferons produced by hematopoietic cells protect mice against lethal infection by mammalian reovirus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1349–1358. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junt T, Moseman EA, Iannacone M, Massberg S, Lang PA, Boes M, Fink K, Henrickson SE, Shayakhmetov DM, Di Paolo NC, et al. Subcapsular sinus macrophages in lymph nodes clear lymph-borne viruses and present them to antiviral B cells. Nature. 2007;450:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmuller W, Torabi-Parizi P, Subramanian N, Lammermann T, Germain RN. A spatially-organized multicellular innate immune response in lymph nodes limits systemic pathogen spread. Cell. 2012;150:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Kato H, Kumar H, Matsui K, Morii E, Aozasa K, Kawai T, Akira S. Alveolar macrophages are the primary interferon-alpha producer in pulmonary infection with RNA viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Wu J, Gao D, Wang H, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science. 2013;341:1390–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1244040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Guerrero DV, Meza-Perez S, Ramirez-Pliego O, Santana-Calderon MA, Espino-Solis P, Gutierrez-Xicotencatl L, Flores-Romo L, Esquivel-Guadarrama FR. Rotavirus infection activates dendritic cells from Peyer's patches in adult mice. Journal of virology. 2010;84:1856–1866. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02640-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fontecha A, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Dendritic cell migration to peripheral lymph nodes. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2009:31–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71029-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M, Williams AJ, Chen G, Collins T, Thanos D. Recruitment of CBP/p300 by the IFN beta enhanceosome is required for synergistic activation of transcription. Molecular cell. 1998;1:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Brown BD, Shay T, Gautier EL, Jojic V, Cohain A, Pandey G, Leboeuf M, Elpek KG, Helft J, et al. Deciphering the transcriptional network of the dendritic cell lineage. Nature immunology. 2012;13:888–899. doi: 10.1038/ni.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moltedo B, Li W, Yount JS, Moran TM. Unique type I interferon responses determine the functional fate of migratory lung dendritic cells during influenza virus infection. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002345. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio M, Ni J, Feng P, Dixit VM. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science. 1997;278:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myskiw C, Arsenio J, Booy EP, Hammett C, Deschambault Y, Gibson SB, Cao J. RNA species generated in vaccinia virus infected cells activate cell type-specific MDA5 or RIG-I dependent interferon gene transcription and PKR dependent apoptosis. Virology. 2011;413:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzalli MH, Knipe DM. Cellular sensing of viral DNA and viral evasion mechanisms. Annual review of microbiology. 2014;68:477–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Rehwinkel J, Kato H, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Way M, Schiavo G, Reis e Sousa C. Activation of MDA5 requires higher-order RNA structures generated during virus infection. Journal of virology. 2009;83:10761–10769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00770-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke AJ, Kastenmuller W, Espinosa DA, Gerner MY, Tse SW, Sinnis P, Germain RN, Zavala FP, Cockburn IA. Lymph-Node Resident CD8alpha+ Dendritic Cells Capture Antigens from Migratory Malaria Sporozoites and Induce CD8+ T Cell Responses. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1004637. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SB, Sorensen LN, Malmgaard L, Ank N, Baines JD, Chen ZJ, Paludan SR. Type I interferon production during herpes simplex virus infection is controlled by cell-type-specific viral recognition through Toll-like receptor 9, the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein pathway, and novel recognition systems. Journal of virology. 2007;81:13315–13324. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01167-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reizis B, Bunin A, Ghosh HS, Lewis KL, Sisirak V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: recent progress and open questions. Annual review of immunology. 2011;29:163–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio D, Xu RH, Remakus S, Krouse TE, Truckenmiller ME, Thapa RJ, Balachandran S, Alcami A, Norbury CC, Sigal LJ. Crosstalk between the type 1 interferon and nuclear factor kappa B pathways confers resistance to a lethal virus infection. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson C, Hausmann J, Lauterbach H, Schmidt M, Akira S, Wagner H, Chaplin P, Suter M, O'Keeffe M, Hochrein H. Survival of lethal poxvirus infection in mice depends on TLR9, and therapeutic vaccination provides protection. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI33940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenten D, Medzhitov R. The control of adaptive immune responses by the innate immune system. Advances in immunology. 2011;109:87–124. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387664-5.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler P, Aichele P, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Schwendener RA. Crucial role of marginal zone macrophages and marginal zone metallophils in the clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. European journal of immunology. 1997;27:2626–2633. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal LJ, Crotty S, Andino R, Rock KL. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to virus-infected non-haematopoietic cells requires presentation of exogenous antigen. Nature. 1999;398:77–80. doi: 10.1038/18038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland DB, Ranasinghe C, Regner M, Phipps S, Matthaei KI, Day SL, Ramshaw IA. Evaluating vaccinia virus cytokine co-expression in TLR GKO mice. Immunology and cell biology. 2011;89:706–715. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M, Colonna M. Unraveling the functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells during viral infections, autoimmunity, and tolerance. Immunological reviews. 2010;234:142–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M, Wang Y, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to systemic but not local antiviral responses to HSV infections. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003728. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani V, Chaudhri G, Eldi P, Karupiah G. The orchestrated functions of innate leukocytes and T cell subsets contribute to humoral immunity, virus control, and recovery from secondary poxvirus challenge. Journal of virology. 2013;87:3852–3861. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03038-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabret N, Blander JM. Sensing microbial RNA in the cytosol. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:468. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage 'suicide' technique. Journal of immunological methods. 1989;124:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgin HW. Pathogenesis of viral infection. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields' virology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 335–336. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Hussain S, Wang EJ, Wang X, Li MO, Garcia-Sastre A, Beg AA. Lack of essential role of NF-kappa B p50, RelA, and cRel subunits in virus-induced type 1 IFN expression. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:6770–6776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Chen ZJ. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annual review of immunology. 2014;32:461–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RH, Cohen M, Tang Y, Lazear E, Whitbeck JC, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Sigal LJ. The orthopoxvirus type I IFN binding protein is essential for virulence and an effective target for vaccination. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:981–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RH, Remakus S, Ma X, Roscoe F, Sigal LJ. Direct presentation is sufficient for an efficient anti-viral CD8+ T cell response. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000768. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RH, Rubio D, Roscoe F, Krouse TE, Truckenmiller ME, Norbury CC, Hudson PN, Damon IK, Alcami A, Sigal LJ. Antibody inhibition of a viral type 1 interferon decoy receptor cures a viral disease by restoring interferon signaling in the liver. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002475. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.