Abstract

Infant mental health is an interdisciplinary professional field of inquiry, practice, and policy that is concerned with alleviating suffering and enhancing the social and emotional competence of young children. The focus of this field of practice is supporting the relationships between infants and toddlers and their primary caregivers to ensure healthy social and emotional development. Notably, the connection between early life experiences and lifelong health has been well established in the scientific literature. Without appropriate regulation from a supportive caregiver, exposure to extreme stressors in early childhood can result in wide-ranging physiological disruptions, including alterations to the developing brain and immune, metabolic, and cardiovascular systems. As part of this interdisciplinary team, pediatric primary care clinicians are in a unique position to incorporate infant mental health practice tenets during their frequent office visits with infants and toddlers. This article provides pediatric primary care clinicians with an overview of infant mental health practice and suggestions for the conscious promotion of positive early relationships as an integral component of well-child care.

Keywords: Infants, mental health, attachment, behavior/behavioral problems

Everything begins in the beginning.

–Layli Maparyan

The term infant mental health encompasses the full continuum of health promotion, prevention, and intervention that addresses the social and emotional health of infants and toddlers (Zeanah, Stafford, Nagle, & Rice, 2005). Infants and very young children experience stress, and it is both the caregiving relationship and environment that shape not only physical and cognitive development, but just as importantly, the child's emotional development (Shonkoff, Lippitt, & Cavanaugh, 2000). In this article we define infant mental health (IMH), discuss the origins of the IMH field and the primary tenets of IMH practice, describe resources and interventions designed to promote IMH, and advocate for the conscious promotion of positive early relationships as an integral component of well-child care.

DEFINITION OF INFANT MENTAL HEALTH

Zero to Three, a national organization dedicated to research, policy, and practice efforts on behalf of infants, toddlers, and families, defines IMH as young children's capacity to experience, regulate, and express emotions, form close and secure relationships, and explore the environment (Zero to Three, 2001). These capacities are best accomplished within a caregiving environment encompassing family, community, and cultural expectations, and they are the cornerstone of healthy social and emotional development (Zero to Three, 2001). Notably, the discipline of IMH considers “infancy” as a developmental stage beginning prenatally and ending at age 3 years, in contrast to the pediatric health care definition of birth to 1 year (Zeanah, 2009). Given the vital importance of both the prenatal and postnatal environment, advocates in the field of IMH maintain that the promotion of mental health in young children must begin much earlier than birth (Champagne, 2010; Zeanah et al., 2005). Additionally, the first 3 years of the human lifespan mark a critical time for rapid brain growth and development (Schore, 2005). During this time children are scheduled for multiple well-child examinations, which provide opportunities for pediatric primary care providers (PCPs) to promote IMH, because they are often the first port of entry for an infant and family into a system of care (Zeanah, 2009).

THE ORIGINS OF INFANT MENTAL HEALTH

In the mid twentieth century, a growing interest in child development and the role of early childhood experiences sparked a large body of research, providing the foundation for what is now considered the field of IMH. Anna Freud had a major influence on this movement, extending classic psychoanalytic theory to include the influence of psychological, social, and emotional development during childhood (Freud, 1965). The developmental psychologist Erikson complimented Freud's work, theorizing that healthy development across childhood occurs within the context of healthy family relationships and cultural contexts (Erikson, 1950). During this time, the field was also greatly influenced by Bowlby's (1958; 1969) pioneering work on attachment theory, which promoted an understanding that primary caregiving relationships lay the foundation for social and emotional development. Attachment theory was later expanded by Ainsworth, who noted that sensitive and consistent caregivers had securely attached relationships with their infants, whereas less sensitive, inconsistent, and unavailable mothers had attachment relationships that were insecure (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). Donald Winnicott, a pediatrician and psychoanalyst, also described the importance of maternal caregiving behavior. Winnicott specifically described “holding” the child, both physically and within the mind, as an essential component of maternal care that serves to facilitate the development of early emotional capacities (Winnicott, 1960).

The term “infant mental health” was first coined by Selma Fraiberg in the 1970s, as she and her colleagues developed an innovative approach to working with families through observations of the mother and infant and their interaction with one another (Fraiberg, Adelson, & Shapiro, 1975; Shapiro, Fraiberg, & Adelson, 1976). With a focus on strengthening relationships between parents and children in vulnerable families, the approach developed in Fraiberg's Child Development Project continues to influence modern IMH models of prevention, assessment, and treatment (Shapiro, 2009). In the seminal paper Ghosts in the Nursery, Fraiberg, Adelson, and Shapiro (1975) explored the intergenerational transmission of attachment disorders and described the influence of past family trauma (or “ghosts”) on current parenting behaviors. Based on this concept, Lieberman developed child-parent psychotherapy, a psychoanalytic approach to treating disturbed infant-parent dyads within the context of the primary attachment relationship (Lieberman, Van Horn, & Ippen, 2005). Furthermore, Lieberman and colleagues described Angels in the Nursery, encouraging the use of positive caregiving experiences to help parents overcome past trauma (Lieberman, Padrón, Van Horn, & Harris, 2005).

Many contemporary scholars have continued to develop and expand upon the field of IMH. Stern, for example, brought attention to the challenges and experiences of transitioning to motherhood, termed the “motherhood constellation” (Stern, 2006). Zeanah has also been very influential, editing the Handbook of Infant Mental Health, as well as proposing a means for diagnosing and categorizing attachment disorders (Boris & Zeanah, 1999; Zeanah et al., 1997). Fonagy and colleagues have described the role of reflective functioning, or the ability to recognize the mental states of one's self and others, as instrumental to development in early childhood. Parental reflective functioning refers to a parent's ability to recognize her own mental states, as well as the mental states of her child, and has been demonstrated to have a significant impact on attachment security and IMH (Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991; Fonagy & Target, 1997; Ordway, Sadler, Dixon, & Slade, 2014; Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005).

THE IMPORTANCE OF RELATIONSHIPS IN EARLY CHILDHOOD TO HEALTH OUTCOMES

The connection between early life experiences and lifelong health has been well established in the scientific literature (Friedman, Karlamangla, Gruenewald, Koretz, & Seeman, 2015; Shonkoff et al., 2012). Starting in the third trimester of pregnancy and continuing through toddlerhood, the brain undergoes rapid growth, and by as early as 8 weeks of life, infants develop advanced social and emotional capacities (Chiron et al., 1997; Korkmaz, 2011; Schore, 2001). Emotional communication between the caregiver and infant, including mutual gaze, facial expressions, and empathetic vocalizations, serve to promote synchrony within the dyad, and in turn, self-regulatory capacities within the infant are developed (Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999; Schore, 2005). Throughout the remainder of infancy, caregivers continue to facilitate social and emotional development by regulating arousal of the child through sensitivity and attunement to the child's internal states. Although this synchrony may occasionally be disrupted, the caregiver's ability to actively repair the relationship helps the infant learn to tolerate brief negative relational experiences (Reck et al., 2004; Schore, 2005).

Supportive caregiving relationships in early childhood are also crucial for biological development (Hostinar, Sullivan, & Gunnar, 2014; Shonkoff et al., 2012). Without appropriate regulation from a supportive caregiver, exposure to extreme stressors in early childhood can result in wide-ranging physiolog ical disruptions, including alterations to the developing brain and neuroendocrine, immune, metabolic and cardiovascular systems (Danese & McEwen, 2012; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Johnson, Riley, Granger, & Riis, 2013). These biological changes are associated with consequences in childhood ranging from obesity and growth delay to impaired cognitive, socioemotional, and language skills (Garner, 2013; Johnson et al., 2010; Wilson & Sato, 2014). Furthermore, these biological changes can lead to physical and mental health problems in adulthood including alcoholism, substance abuse, depression, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes (Garner, 2013). Thus, by supporting IMH through caregiver-child relationships, PCPs can play an essential role in laying the foundation for lifelong health.

...by supporting IMH through caregiver-child relationships, PCPs can play an essential role in laying the foundation for lifelong health.

THE TENETS OF INFANT MENTAL HEALTH CLINICAL PRACTICE

There are three primary tenets governing competent, clinical IMH practice. These include a strengths-based perspective, approaching assessment and intervention within a relational framework, and viewing development within a cultural context (Zeanah, 2009). Contrary to traditional models of mental health practice that focus on symptomatology and impairment in functioning, IMH places emphasis on the positive attributes and supports inherent in a family system. With a strength-based perspective, it is the assessment of existing strengths that drives the plan for mobilization of additional supports and intervention. Careful cultivation and attention to relationships is the second tenet to effective IMH practice. Specifically, IMH practice dictates that all levels of relationships (supervisor to practitioner, practitioner to parent, and parent to child) are interdependent and influence one another (Weatherston, Kaplan-Estrin, & Goldberg, 2009). The third tenet of IMH involves an understanding that human development occurs within cultural and environmental contexts. A child's behavior often changes across different environments, and thus it is important to remember that a single observation provides only a “snapshot” of the child's overall behavior and functioning (Zero to Three, 2005). Additionally, IMH professionals must be aware of the individual experiences, family beliefs, and cultural perspectives that influence child-rearing practices (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2008).

THE CLINICAL FRAMEWORK FOR INFANT MENTAL HEALTH PRACTICE

Infant mental health is an interdisciplinary professional field of inquiry, practice, and policy that is concerned with enhancing the social and emotional competence of young children (Zeanah, 2009). Because of the simultaneous nature of the needs of infants and families, intervention with this population never occurs in isolation. The identified client is not the mother, father, or baby, but rather the relationship system (Zero to Three, 2005). When working with a family, IMH professionals appreciate the parent's experience of the child, as well as the child's experience of the parent. Additionally, the needs of a family are rarely restricted to mental health; medical attention, developmental resources, child care, financial support, and other concrete needs are part of a comprehensive assessment profile (Siegel et al., 2012). An effective, culturally sensitive assessment can be an intervention in itself, because this gives a family an opportunity to give voice to their story, to prioritize their unique needs, and to recognize the infant as a participant in the relationship (Zeanah & Zeanah, 2010; Zero to Three, 1994).

Little more than three decades ago, clinicians working with infants and families were limited in their ability to assess, classify, and diagnose disorders present in the infant and the parent-infant relational system. In response, a multidisciplinary task force of infant development and mental health experts was established in 1987 to review evidence and describe categories of IMH disorders. As a result of this task force, the DC 0-3: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood was published in 1994. The goal of the DC 0-3 was to provide initial classification criteria to advance professional communication, clinical formulation, and research. The DC 0-3 was developed to complement existing frameworks such the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), with an emphasis on symptomatology and developmental disorders unique to infancy and toddlerhood (Zero to Three, 1994, 2005).

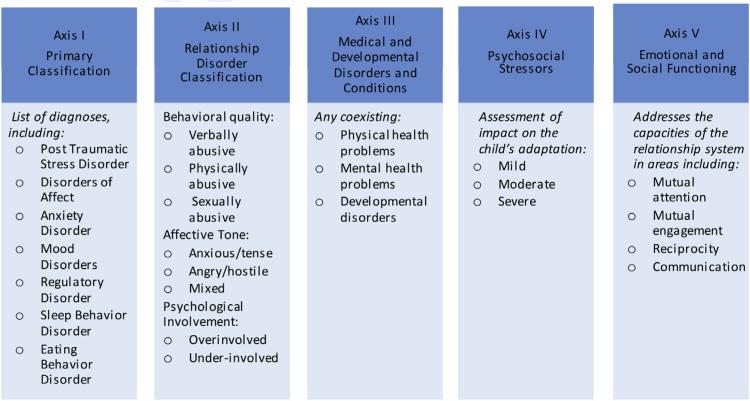

The purpose of the DC 0-3 is not to label young children with a mental health diagnosis but to identify and classify disorders in order to provide effective early intervention. The DC 0-3 classification is organized into five descriptive axes to provide clinicians with a comprehensive diagnostic profile (Figure 1). The DC 0-3 does not require that clinicians identify a problem within each axis but is intended to serve as a guide for evaluating the multidimensional aspects of IMH. Most recently revised in 2005, the DC 0-3R retains a five-axis classification system similar to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Although this five-axis system is no longer present in the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), the DC 0-3R continues to provide a useful organization scheme for clinicians in assessing and diagnosing infant mental health problems (Zero to Three, 1994, 2005). A revised DC:05 (to be released in 2016) will be expanded to include children from birth to 5 years and will address the changes reflected in the DSM-V (DC:0-3R Revision Task Force, 2015).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the DC: 0-3 classification system.

The DC 0-3 is particularly useful for clinicians who care for very young children, because it allows for individual differences in developmental progression and assessment across settings and takes into account the infant's role as a participant in relationships. To use the DC 0-3 effectively, assessment should occur over the course of several weeks and involve the primary caregiver. Information should be obtained from multiple sources (e.g., observation, clinical interviews, and written instruments) and various environmental contexts (e.g., clinic, home, and community). In addition to considering the child's relationship with the primary caregiver, clinicians using the DC 0-3 also should consider the child's relationships within the context of the extended family, child care providers, community, and culture. With awareness that each infant is unique, this classification system can be used by clinicians to create a comprehensive developmental profile to identify strengths, difficulties, and areas in need of intervention within the family system (Zero to Three, 1994, 2005).

INFANT MENTAL HEALTH INTEGRATED INTO PEDIATRIC PRACTICE

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that PCPs conduct 14 routine screenings between the prenatal period and 3 years of age (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014), providing ample opportunity for universal approaches to IMH screening and intervention. PCPs have an excellent opportunity to assess for attunement between the dyad, as well as educate caregivers on strategies to improve the caregiver-child relationship. PCPs are commonly solicited for advice on developmental-related issues that may lead to IMH disruptions, such as sleep or feeding disturbances, language abnormalities, or aggressive behavior, offering an important opportunity for anticipatory guidance or intervention. Primary care visits also provide an opportunity to identify the needs of the caregiver, which, in turn, will benefit the child and the caregiver-child relationship. By incorporating the tenets of IMH into primary care practice, PCPs can play a key role in supporting IMH from the beginning of life.

Primary care visits also provide an opportunity to identify the needs of the caregiver, which, in turn, will benefit the child and the caregiver-child relationship.

Aligned with the strength-based perspective of IMH practice, it is essential for PCPs to identify a caregiver's strengths and empower caregivers to provide supportive, sensitive care. Beginning early in life, infants respond rhythmically to their mother's voice, imitate their mother's smiles, and understand their mother's cues (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001). PCPs can emphasize the mutual reciprocity that exists between the mother and infant and use the observation of positive interactions as opportunities for praise. If a caregiver calms her crying baby, the PCP can praise her efforts and empathize with how stressful it can be to listen to a crying infant. Simple observations such as, “Look at how he is looking at you” or “You are so gentle with him, he likes that,” can provide parents with a feeling of confidence and inspire continued responsive behavior.

IMH assessment and intervention within a primary care setting also should occur within a relational framework, and pediatric PCPs are in an ideal position to establish an open, trusting relationship with the caregiver and infant (Zeanah, 2009). The development of these relationships begins with the clinician's reflective stance: a stance of curiosity, openness, willingness to listen, and acceptance of differences and uncertainty (Ordway et al., 2014; Slade, 2005). During an office visit, the PCP can take a reflective stance that includes using open-ended questions and an active listening style. It may help to wonder with the care-giver, “I wonder why he is doing that,” allowing the caregiver to consider the motivation or intents behind the child's behavior. It also can be helpful for the PCP to acknowledge the challenges of parenthood, allowing caregivers to express their frustrations and anxieties. For example, if a caregiver is upset that her child is climbing on a table, this response can be reframed to help the caregiver understand that climbing represents a natural curiosity that is expected at the child's age, and the PCP can suggest approaches to keep the child safe while also understanding his or her behavior. This interaction allows the PCP to actively provide anticipatory guidance and model a supportive interaction while maintaining a positive, reflective stance. Problem solving, intervention modalities, and goal setting are important components of IMH practice; however, it is the stance (i.e., the attitude, disposition, value system, and philosophy) of the PCP that determines the development of the relationship.

The third tenet of IMH is an understanding that a child's development occurs within cultural and environmental contexts. To put this understanding into practice, PCPs must carefully balance their clinical knowledge with the individual experiences, culture, and circumstances of the caregiver (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2011). For example, family caregiving practices may lead a new mother to believe that holding her newborn often will “spoil” him. In her family, care-givers may have learned not to become too attached to their infants, a self-protective measure resulting from experiences of trauma or loss. In this instance, the PCP can explore with the mother how her own feelings and intentions fit within her family culture and beliefs about caregiving. Providing education and fostering the mother's sense of competence may provide the tools she needs to parent her child differently, or in keeping with the family culture, other ways of soothing the baby that don't involve frequent holding could be explored.

In the next section a case study is provided to exemplify the integration of IMH tenets into pediatric practice. The PCP facilitates a fluid and ongoing assessment of the caregiver's mental state and the caregiver-child relationship throughout the context of the visit.

CASE STUDY

Angela, a 23-year-old African American woman, presents with her 10-week-old son, Joseph, for a routine visit. The PCP has formed a relationship with Angela, because she has attended all her previously scheduled previous appointments.

PCP: “How are you doing today, Angela?”

The PCP begins the visit by asking Angela about her own well being to assess her mental state. This assessment is particularly important after the birth of a new child or after a parent has returned to work, because these stressful experiences can elicit many emotions.

A: “I'm fine.”

PCP: “Tell me a little more about how you are feeling.”

The PCP senses an unhappy response from Angela and uses a reflective stance and open-ended questions to gently explore her feelings. Angela is given the opportunity to open up about her concerns, and the growing relationship between the mother and the PCP is enhanced.

A: “I'm just so tired. I've gone back to work and it's really stressing me out. Joseph seems all right during the day, but he just can't seem to stop crying when I get home.”

The PCP asks for more details in order to better assess the quality and frequency of the Joseph's crying, as well as to understand how Angela perceives the crying.

PCP: Can you tell me a bit more about the crying? When did it start? Does anything help to soothe Joseph?

A: “It started about a week ago. He's fine during the day, but it starts up around 5 pm. It probably lasts for 2 or 3 hours, but it feels like forever. It's not normal. My friend has a baby the same age and he is fine—he cries a little and then stops. My mother-in-law says I am spoiling him by holding him all the time and he needs to cry it out.”

Based on Angela's tone and expression, the PCP recognizes that this is a very distressing experience for her. The PCP also recognizes that the advice and experiences of her support systems are adding to Angela's anxiety.

PCP: “You sound worried about your baby. When you hear about your friend's baby, how does that make you feel?”

By recognizing Angela's experience, the PCP provides validation and support, and also uses this opportunity to further explore Angela's emotions.

A: “I feel I am not doing a good job.”

The PCP describes the normality of crying and the developmental pattern of crying to be expected at this age. The PCP also acknowledges the frustrations of parenthood, and provides reassurance.

PCP: “Crying is very normal at this age, and all babies are different. Babies have different temperaments and some may get upset more easily, but that doesn't mean you are a bad parent. Let me take a look at him to see if he is healthy, and then we will talk about some ways you can help Joseph when he's crying.”

During the child's physical examination, the PCP observes the interaction between the mother and infant. The PCP notes whether Angela is attuned and responsive to Joseph's signals. The PCP notes that although Joseph is not rolling yet, Angela instinctively is aware that he is active and can potentially fall from a high surface.

PCP: “I'm glad you have a hand on him because I bet he can wriggle—he will be moving and rolling soon!”

The PCP uses this opportunity to praise Angela for her attentiveness, as well as include anticipatory guidance. As Angela undresses her baby, the PCP reviews the child's history. She completes his physical examination, which is within normal limits. Angela expresses relief that her baby is well.

PCP: “When babies cry it can be very stressful, but there are many things that you can do to help soothe him. I can see that you are taking good care of him, and that you two have a special bond. Just look at the way he's looking at you!”

In addition to education and anticipatory guidance, the PCP praises Angela. The PCP emphasizes the reciprocity of the maternal-child relationship, highlighting how Joseph is using his mother's face to mirror expression.

PCP: “It's also very important for you to take care of yourself, so that you can take care of Joseph as best you can. Let's talk about some things that can help you when you're feeling stressed.”

The PCP discusses with Angela the importance of self-care in order to promote a healthy caregiver-child relationship. The PCP discusses strategies for stress relief and provides information on new-mother support groups in the local area. The PCP also uses this opportunity to screen for depression, provides anticipatory guidance on the symptoms of postpartum depression, and encourages Angela to report any symptoms immediately. As the visit comes to an end, Angela expresses her appreciation and notes that she feels better about how she is understanding her baby's capabilities, needs, and cues.

CASE DISCUSSION OF INFANT MENTAL HEALTH STRATEGIES

Crying is a common concern of many caregivers and often presents a “portal of entry” for assessing the caregiver-child relationship. As demonstrated in the case, it is important not only to determine whether an infant's crying is developmentally appropriate but to identify how this crying is perceived by the caregiver, because this can have a significant impact on her level of stress and the way she interacts with her child. This case also demonstrates the importance of anticipatory guidance; if the expected increase in crying had been discussed at the previous office visit, the distress related to this developmental change may have been prevented. Starting the visit with a simple open-ended question such as “How are you?” or “How is work going?” not only provides the PCP with information about the caregiver but provides the caregiver with an opportunity to express her feelings or concerns. In contrast, if the session starts with “What is the problem?” or “What is going on with your son?” the PCP may miss an opportunity to assess the caregiver's mental state.

A caregiver's ability to facilitate her child's development through supportive interactions is largely dependent on her ability to regulate her own internal states; however, this task is often a challenge for care-givers who may display irritability, hostility, or disengagement toward their child as a result of their own history of depression, psychopathology, or complex trauma (Schore, 2005; Tang, Reeb-Sutherland, Romeo, & McEwen, 2014; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Martins & Gaffan, 2000). Complex trauma refers to early and ongoing forms of trauma, such as abuse, neglect, or exposure to violence that occurs repeatedly over time and within family or other close relationships. Symptoms of complex trauma include an interrelated constellation of posttraumatic psychological adaptations such as problems with affect regulation, dissociation, negative self-perceptions, inability to trust, somatic complaints, hopelessness, and despair (Courtois, 2004). Although the effects of complex trauma can be difficult to recognize in primary care practice, the resulting impairments to attachment relationships can have a profound influence on later caregiving abilities (Slade & Sadler, 2013). Thus, it is crucial for PCPs to assess for mental health risks, because these early traumas can significantly influence caregivers’ abilities to form healthy relationships with their children. The use of a reflective stance, offering education and support and providing follow-up care, may help alleviate a caregiver's distress and prevent a disruption within the caregiver-child relationship. However, some families may require a more in-depth intervention, such as referral to a home visiting based program, or treatment for the presence of depression or complex trauma.

RED FLAGS AND INDICATIONS FOR POSSIBLE INFANT MENTAL HEALTH REFERRAL

In the primary care setting, it often can be challenging to determine if a child's behavior is a natural variation of normal development or a disruption within the caregiver-child dyad. Establishing a relationship with the family and following the child closely over time will provide further insight into the problem and allow for diagnosis, education, or referral to an intervention as necessary. To assist PCPs with this assessment, several brief screening tools are available to assess an infant's social and emotional health (Carter, Briggs-Gowan, & Davis, 2004). Common screening instruments include the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social-Emotional (Briggs et al., 2012) and the Brief Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Irwin, Wachtel, & Cicchetti, 2004). Each of these screening instruments can be completed by the caregiver in about 10 minutes and scored by a clinician in 1 to 2 minutes prior to the office visit.

PCPs also must be aware of important risk factors and red flags. Zeanah (2009) describes four domains that represent red flags with respect to IMH: the infant (e.g., prematurity, health problems, difficult temperament, developmental delays, and autism spectrum disorders [ASDs]); parent/caregiver factors (e.g., unwanted pregnancy, history of losses, and past trauma); dyad relationship (e.g., lack of warmth, harsh handling, and unrealistic expectations), and environment (e.g., poverty, teenage parents, and a low level of education). PCPs must assess for these red flags and intervene as necessary topromoteIMH and restore a healthy relationship within the dyad. A number of resources and interventions are available to support infant mental health, including home visiting interventions, early intervention programs, and psychotherapy. A list of widely available resources for clinicians, as well as specific local and national interventions, is presented in the Table.

TABLE.

Resources available to primary care providers

| Title | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Training | ||

| IMH Associations | www.mi-aimh.org | At least 20 states have an IMH Association |

| Child Health and Development Institute in Connecticut | www.chdi.org | Offers free training to pediatric providers across a range of topics, including behavioral health concerns and maternal depression screening |

| World Association for Infant Mental Health | www.waihm.org | Individual membership available with a year-long subscription to the Infant Mental Health Journal; members include representatives from many countries throughout the world |

| Online resources | ||

| American Academy of Pediatrics Early Brain and Child Development | www.aap.org/ebcd | Resources for clinicians to teach and learn about IMH |

| Circle of Security | www.circleofsecurity.net | Videos, handouts, and a depiction of the Circle of Security circle for use during patient visits |

| Brazelton Touchpoints Center | www.brazeltontouchpoints.org | Provides comprehensive resources for families and providers to promote healthy development through low-cost, sustainable interventions |

| Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families | www.zerotothree.org | Web site and Zero to Three journal; a national, nonprofit organization with information for parents, professionals, and policymakers |

| Center on the Developing Child | www.developingchild.harvard.edu | Features the research, resources, and policy work on early experiences, toxic stress, and brain architecture; of particular interest: a featured video on early childhood mental health |

| Useful publications | ||

| “Ghosts in the nursery” | Fraiberg et al. (1975) | Seminal paper providing much of the foundation for IMH practice and interventions |

| Psychotherapy with infants and young children | Lieberman & Van Horn (2008) | Presented in case studies, examines the theoretical underpinnings of parent-infant psychotherapy and clinical implications |

| Attachment theory | Bowlby (1988) | Features a collection of lectures given by Bowlby on research findings and clinical implications of attachment theory |

| Attachment theory | Bowlby (1969) | Highlights clinical and experimental explorations of attachment theory |

| Mother-infant relationships | Stern (1977) | Based on Stern's video-based research into mother-infant interaction, this work has helped to inform theory development around mother-infant attunement and reading infant cues |

| Parental reflective functioning | Slade (2005) | An overview of the theory of reflective functioning and what it looks like in the parent-child relationship |

| Ordway, Sadler, Dixon, & Slade (2014) | Includes specific examples for building parental reflective functioning in primary care practice | |

| Bright Futures | Hagan et al. (2008) | Specific strategies and questions to support early relationships |

| Handbook of Infant Mental Health | Zeanah (2009) | The prominent text in the field, this reference addresses research and clinical aspects of IMH |

| DC: 0-3 Manual | Zero to Three (2005) | A manual and casebook for diagnosis and treatment of mental health and developmental disorders in children from birth to 3 years |

Note. IMH = infant mental health.

Characteristics of the infant can provide insight into the child's social and emotional development and alert the PCP to red flags that require support, increased screening (e.g., to diagnose ASD), or intervention. Possible red flags in the young child include deficits in social and communicative function, aggression, anxiety, or the experience of trauma. As early as 12 months, infants may exhibit behaviors indicative of ASD such as social impairment, communication deficits, abnormal motor development and sensory processing, and the emergence of restricted or repetitive behaviors (see Carr & Lord, 2009). It is recommended that PCPs screen all children for risk of developmental disorders using stan dardized developmental screeners at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month well-child visits (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006). Early identification is critical to the well-being of children and their families, and comprehensive intervention that includes education and support for both the child and caregiver is the hallmark of effective programs.

Characteristics of the infant can provide insight into the child's social and emotional development and alert the PCP to red flags that require support, increased screening (e.g., to diagnose ASD), or intervention.

Tantrums and defiance can be part of normal toddler behavior, and parents can be advised to set limits and assist their child with self-regulation skills. However, excessive aggression that does not improve may require a referral to more specialized care. Anxiety is also a common behavior in infancy, particularly between 7 to 12 months of age when children begin to exhibit stranger anxiety. Although many children cling to their primary caregiver and are fearful of new situations, a referral may be indicated if the child is avoidant of settings associated with fearful situations, the fear occurs daily, or it is interfering with regular family activities. In young children, symptoms of posttraumatic stress may occur after a single exposure to trauma, such as a car accident, or repeated events, such as chronic sexual abuse. Without intervention, young children may regress developmentally, become very fearful to be alone, or have inappropriate sexual behaviors (Zero to Three, 2005).

A number of caregiver factors also may place infants at risk for disrupted IMH, with possible red flags including unwanted pregnancy, past or current domestic violence, or a mental health disorder. The complexities of unintended pregnancy may have long-term effects on both the mother and child, and thus a reflective stance may allow the PCP to assess the caregiver's emotions around the child's birth. A caregiver's substance abuse also may affect a child's health, as well as the caregiver-child relationship. In these cases, intervention is often required to prevent or address IMH disorders (Suchman, DeCoste, Ordway, & Mayes, 2012).

IMH INTERVENTIONS AND PROGRAMS

As noted previously, two early IMH interventions have provided a framework for practice across many disciplines in the field: infant-parent psychotherapy (IPP) and child-parent psychotherapy (CPP; Fraiberg et al., 1975; Lieberman & Van Horn, 2008). Several themes inherent in both IPP and CPP have become core principles of the way clinicians work with infants and families today. Revealing the baby's voice to the parent, conjuring the “ghosts” or unresolved conflicts from the parent's past, narrating experience, using language to describe feelings, meeting families literally where they are (home and community), and using concrete services (food, clothing, and housing) as a point of entry are integral components of multiple program models that exist along the promotion, prevention, and intervention continuum of the IMH field (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2008).

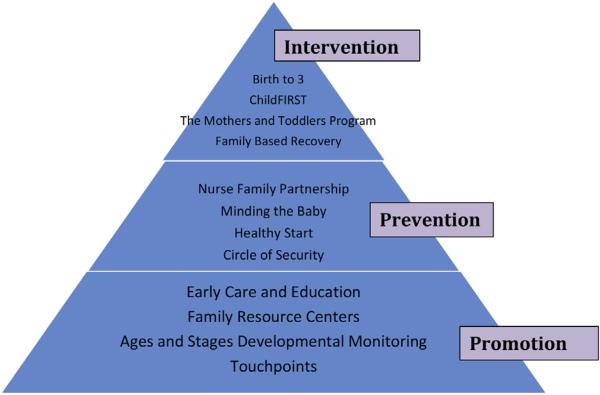

During the past decade, a number of studies have examined the effects of various relationship-based programs ranging from health promotion to intervention (Figure 2). These studies have yielded promising outcomes, suggesting that impaired mother-infant attachment relationships can be repaired and possibly prevented (Moran, Pederson, & Krupka, 2005; Sadler et al., 2013; Suchman et al., 2012). For example, Sadler and colleagues (2013) conducted a randomized controlled trial of Minding the Baby, a home visiting intervention for young, urban, first-time mothers with a focus on enhancing parental reflective functioning. Results have suggested positive maternal and child outcomes, as well as a positive impact on the maternal-child relationship (Ordway, Sadler, Dixon, Close, et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013). Additionally, a study by Schechter et al. (2006) found that clinician-assisted video feedback helped traumatized mothers to imagine the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of their child, thus allowing less defensiveness and more tolerance of their child's potential fears and worries.

FIGURE 2.

A pyramid of infant mental health programs.

Health promotion model programs to enhance infant mental health.

A number of other resources and programs are available to support IMH at the promotion, prevention, and intervention levels (see Figure 2). The Circle of Security is a widely used attachment-based early intervention method designed to help caregivers provide a secure base/safe haven for their children (Zeanah, 2009). The focus of Circle of Security is to support the caregiver to be bigger, stronger, wiser, and kind, and to adjust each of these qualities to suit the child's need in a particular moment or situation. Application of this intervention within the context of a trusting, structured relationship helps caregivers to be more proficient at tuning in to their child's needs (Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, & Powell, 2006).

The early years are a critical time for human development, and there is almost always an opportunity for repair. However, although there are an abundance of promising IMH interventions, the work of IMH is often difficult and can elicit strong emotions from all persons involved. Thus, reflective supervision is an essential component of IMH programs. Separate from administrative supervision or clinical problem solving, reflective supervision refers to regular collaborative reflection between a clinician and a supervisor that allows for creating a safe, trusting, holding space for the thoughts, feelings, and experiences commonly experienced by IMH practitioners (Parlakian, 2001; Schafer, 2010).

CONCLUSION

The tenets of IMH practice are a natural complement to pediatric primary care practice. Both practice frameworks share goals of enhancing caregiver-child relationships, promoting health, and positively influencing young children's social and emotional experiences. Because of the complexity of IMH problems in young children, comprehensive efforts from PCPs are necessary to prevent IMH problems, minimize their effects, and enhance the competence of young children (Zeanah, 2009). The regularity of routine and acute care visits during the first few years of life provides numerous opportunities for pediatric health care providers to promote infant mental health and a positive caregiver-child relationship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Webb for her thoughtful review and editorial assistance.

Financial support provided by the University of Connecticut Department of Human Development and Family Studies, the FAR Fund, Pritzker Early Childhood Foundation, Seedlings Foundation, Child Welfare Fund, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, The Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Foundation, The Edlow Family Foundation, The Schneider Family, National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RO1HD057947), T32NR008346, and The Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare. This article was made possible by Clinical and Translational Science Award KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth MD, Bell SM. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development. 1970;41:49–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics 2014 Recommendations for pediatric preventive health care. Pediatrics. 2014;133:568–570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Zeanah CH. Disturbances and disorders of attachment in infancy: An overview. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The nature of the child's tie to his mother. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1958;39:350–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs RD, Stettler EM, Silver EJ, Schrag RD, Nayak M, Chinitz S, Racine AD. Social-emotional screening for infants and toddlers in primary care. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e377–e384. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Irwin JR, Wachtel K, Cicchetti DV. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for social-emotional problems and delays in competence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:143–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr T, Lord C. Autism spectrum disorders. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Davis NO. Assessment of young children's social-emotional development and psychopathology: Recent advances and recommendations for practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:109–134. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA. Early adversity and developmental outcomes: Interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and social experiences across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:564–574. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiron C, Jambaque I, Nabbout R, Lounes R, Syrota A, Dulac O. The right brain hemisphere is dominant in human infants. Brain. 1997;120:1057–1065. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy. 2004;41:412–425. [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology and Behavior. 2012;106:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DC:0-3R Revision Task Force . DC:0-3 to DC:0-3R to DC:0-5: A new addition (35) Zero to Three; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Childhood and society. Norton & Co.; New York, NY: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Greenbaum CW, Yirmiya N. Mother-infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:223–231. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Steele H, Steele M. Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment at one year of age. Child Development. 1991;62:891–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Target M. Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:679–700. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1975;14:387–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud A. Normality and pathology in childhood. International Universities Press; New York, NY: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Karlamangla AS, Gruenewald TL, Koretz B, Seeman TE. Early life adversity and adult biological risk profiles. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2015;77:176–185. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AS. Home visiting and the biology of toxic stress: Opportunities to address early childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2013;132:S65–S73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. 3rd ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KT, Marvin RS, Cooper G, Powell B. Changing toddlers' and preschoolers' attachment classifications: The circle of security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1017–1026. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostinar CE, Sullivan RM, Gunnar MR. Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis: A review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:256–282. doi: 10.1037/a0032671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Guthrie D, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA., III Growth and associations between auxology, caregiving environment, and cognition in socially deprived Romanian children randomized to foster vs ongoing institutional care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:507–516. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:319–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz B. Theory of mind and neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. Pediatric Research. 2011;69:101R–108R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318212c177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Padrón E, Van Horn P, Harris WW. Angels in the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:504–520. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Van Horn P, Ippen CG. Toward evidence-based treatment: Child-parent psychotherapy with preschoolers exposed to marital violence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:1241–1248. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181047.59702.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Van Horn P. Psychotherapy with infants and young children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on early attachment. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:737–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran G, Pederson DR, Krupka A. Maternal unresolved attachment status impedes the effectiveness of interventions with adolescent mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:231–249. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Dixon J, Close N, Mayes L, Slade A. Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2014;29:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Dixon J, Slade A. Parental reflective functioning: Analysis and promotion of the concept for paediatric nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23:3490–3500. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlakian R. Look, listen, and learn: Reflective supervision and relationship-based work. Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reck C, Hunt A, Fuchs T, Weiss R, Noon A, Moehler E, Mundt C. Interactive regulation of affect in postpartum depressed mothers and their infants: An overview. Psychopathology. 2004;37:272–280. doi: 10.1159/000081983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, Webb DL, Simpson T, Fennie K, Mayes LC. Minding the baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home-visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2013;34:391–405. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer W. Clinical supervision is a NECESSITY for infant specialists (128) The Infant Crier, Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter DS, Myers MM, Brunelli SA, Coates SW, Zeanah CH, Jr., Davies M, Liebowitz MR. Traumatized mothers can change their minds about their toddlers: Understanding how a novel use of videofeedback supports positive change of maternal attributions. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:429–447. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:7–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. Attachment affect regulation, and the developing right brain: Linking developmental neuroscience to pediatrics. Pediatrics in Review. 2005;26:204–211. doi: 10.1542/pir.26-6-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro V, Fraiberg S, Adelson E. Infant-parent psychotherapy on behalf of a child in a critical nutritional state. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1976;31:461–491. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1976.11822325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro V. Reflections on the work of professor Selma Fraiberg: AAA pioneer in the field of social work and infant mental health. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2009;37:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Lippitt JA, Cavanaugh DA. In: Early childhood policy: Implications for infant mental health. Handbook of infant mental health. 2nd ed. Zeanah CH, editor. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, Wegner LM. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, Garner AS, Pascoe J, Wood DL, Wegner LM. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e224–e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:269–281. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Grienenberger J, Bernbach E, Levy D, Locker A. Maternal reflective functioning, attachment, and the transmission gap: A preliminary study. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:283–298. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Sadler LS. Minding the Baby: Complex trauma and home visiting. International Journal of Birth and Parent Education. 2013;1:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. The first relationship: Infant and mother. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stern D. The motherhood constellation: Therapeutic approaches to early relational problems. In: Sameroff A, McDonough SC, Rosenblum KL, editors. Treating parent-infant relationship problems: Strategies for intervention. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman N, DeCoste C, Ordway MR, Mayes L. Mothering from the inside out: A mentalization-based individual therapy for mothers with substance use disorders. In: Suchman M, Pajulo M, Mayes LC, editors. Parenting and substance addiction: Developmental approaches to intervention. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tang AC, Reeb-Sutherland BC, Romeo RD, McEwen BS. On the causes of early life experience effects: Evaluating the role of mom. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2014;35:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherston DJ, Kaplan-Estrin M, Goldberg S. Strengthening and recognizing knowledge, skills, and reflective practice: The Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health competency guidelines and endorsement process. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2009;30:648–663. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Sato AF. Stress and paediatric obesity: What we know and where to go. Stress and Health. 2014;30:91–102. doi: 10.1002/smi.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott DW. The theory of the parent-infant relationship. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 1960;41:585–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Boris NW, Heller SS, Hinshaw-Fuselier S, Larrieu JA, Lewis M, Valliere J. Relationship assessment in infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1997;18:182–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah P, Stafford B, Nagle G, Rice T. Addressing social-emotional development and infant mental health in early childhood systems (Building State Early Childhood Comprehensive Systems Series No. 12) National Center for Infant and Early Childhood Health Policy; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH. Handbook of infant mental health. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Zeanah P. Infant mental health. In: Lester BM, Sparrow JD, editors. Nurturing children and families: Building on the legacy of T. Berry Brazelton. Blackwell Publishing; Malden, MA: 2010. pp. 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zero to Three . Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. 1st ed. National Center for Clinical Infant Programs; Arlington, VA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zero to Three Infant Mental Health Task Force Steering Committee . Definition of infant mental health. National Center for Clinical Infant Programs; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zero to Three . Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood (revised ed.) National Center for Clinical Infant Programs; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]