Abstract

Background

This study examined the time-variant association between daily minority stress and daily affect among gay and bisexual men. Tests of time-lagged associations allow for a stronger causal examination of minority stress-affect associations compared with static assessments. Multilevel modeling allows for comparison of associations between minority stress and daily affect when minority stress is modeled as a between-person factor and a within-person time-fluctuating state.

Methods

371 gay and bisexual men in New York City completed a 30-day daily diary, recording daily experiences of minority stress and positive affect (PA), negative affect (NA), and anxious affect (AA). Multilevel analyses examined associations between minority stress and affect in both same-day and time-lagged analyses, with minority stress assessed as both a between-person factor and a within-person state.

Results

Daily minority stress, modeled as both a between-person and within-person construct, significantly predicted lower PA and higher NA and AA. Daily minority stress also predicted lower subsequent-day PA and higher subsequent-day NA and AA.

Limitations

Self-report assessments and the unique sample may limit generalizability of this study.

Conclusions

The time-variant association between sexual minority stress and affect found here substantiates the basic tenet of minority stress theory with a fine-grained analysis of gay and bisexual men’s daily experience. Time-lagged effects suggest a potentially causal pathway between minority stress as a social determinant of mood and anxiety disorder symptoms among gay and bisexual men. When modeled as both a between-person factor and within-person state, minority stress demonstrated expected patterns with affect.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, minority stress, gay/bisexual, LGBT, daily diary

Gay and bisexual men are disproportionately burdened with several mental health problems, including mood and anxiety disorders and associated behavioral comorbidity (e.g., substance use problems, HIV risk behavior) compared to heterosexual men (Cochran et al., 2003; Mills et al., 2004). According to minority stress theory, sexual orientation disparities in mental health problems are rooted in sexual minority individuals’ (i.e., individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, or engage in same-sex sexual behavior) disproportionate exposure to minority stress—the stress that accrues to members of socially disadvantaged, or stigmatized, minority groups and compounds general life stress (Meyer, 2003b). Several sexual orientation-specific processes have been argued to contribute to the development of minority stress among sexual minority individuals: (1) the internalization of negative societal attitudes; (2) expectations of stressful events and associated hyper-vigilance; (3) external, objective stressful events and conditions related to one’s sexual minority status; and (4) concealment of one’s sexual orientation (Meyer, 1995). These four processes are referred to as internalized homophobia, rejection sensitivity, discrimination, and concealment, respectively.

Affect refers to the experience of mood and emotions, with mood and anxiety disorders being characterized by disruptions in affective experience, expression, and regulation (Brown et al., 1998; Mineka et al., 1998; Steptoe et al., 2008; Watson, 1988). Positive affect (PA) is characterized by emotions such as alertness, joy, energy, and enthusiasm, while negative affect (NA) is characterized by emotions such as fear, sadness, and serenity. A third affective dimension, anxious affect (AA), has also been described and is characterized by emotional factors specific to anxiety, such as being scared, jittery, and nervous (Clark and Watson, 1991). PA, NA, and AA are domains of the same construct (i.e., affect), but they are orthogonal dimensions that operate independently of each other (Clark et al., 1994; Kercher, 1992; Watson et al., 1995). These affect domains are consistently linked to depression and anxiety, but are each differentially related to these disorders (Brown et al., 1998; Clark and Watson, 1991; Mineka et al., 1998). For example, the tripartite model of affect suggests that PA is negatively related to symptoms of depression, AA is positively related to symptoms of anxiety, and NA is implicated in the development of both depression and anxiety (Brown et al., 1998; Clark and Watson, 1991; Clark et al., 1994; Jolly et al., 1994).

Although several studies have uncovered cross-sectional associations between minority stress and mental health outcomes among gay and bisexual men (e.g., Feinstein et al., 2012; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Mays and Cochran, 2001; Newcomb and Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis et al., 2015), few have examined minority stress, and its association with affect, as a time-varying construct across days (Pachankis et al., 2014a; Pachankis et al., 2011). Further, no known research has examined a potentially time-variant association between minority stress and affect every day across several weeks. To address these gaps, the primary objective of the present study was to examine the possible time-variant association between daily minority stress and daily affect among gay and bisexual men. In addition to examining concurrent associations between daily minority stress and daily affect, this study also sought to determine whether there existed a lagged association between daily minority stress and affect on the subsequent day, an analysis that would provide support for a causal effect of minority stress on affective experience. Finally, multilevel modeling allowed for the modeling of minority stress as both a between-person factor and a within-person time-fluctuating state to determine if affective correlates of minority stress are best explained by variation in minority stress experiences across people or across days within people. Extending traditional approaches that measure inherently time-fluctuating events as global factors, while simultaneously examining within-person daily variation, has yielded important insights for the study of other aspects of gay and bisexual men’s health, such as HIV risk behavior (e.g., Grov et al., 2010a; Mustanski, 2007; Rendina et al., 2015)

Method

These analyses use data from Pillow Talk, a longitudinal study designed to examine mental health and HIV transmission risk among highly sexually active (i.e., nine or more sexual partners in the past 90 days) self-identified gay and bisexual men in New York City (Parsons et al., 2013; Parsons et al., 2015a; Ventuneac et al., 2015). Given that minority stress, depression and anxiety, and sexual vulnerability co-occur among urban-dwelling gay and bisexual men (Halkitis et al., 2012; Pachankis, 2015; Parsons et al., 2015b; Parsons et al., 2012; Stall et al., 2008), this sample is particularly suitable for investigating the co-occurring health threats, including minority stress and mental health-associated affect, facing this population.

Participants and Procedures

Enrollment began in February 2011 and utilized a variety of recruitment strategies: (1) respondent-driven sampling; (2) internet-based advertisements on social and sexual networking websites; (3) email blasts through New York City gay sex party listservs; and (4) active recruitment in New York City venues such as gay bars/clubs, concentrated gay neighborhoods, and ongoing gay community events.

Eligibility criteria included: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) biologically male and self-identification as male; (3) a minimum of nine different male sexual partners in the prior 90 days; (4) self-identification as gay, bisexual, or some other non-heterosexual identity (e.g., queer or pansexual); (5) ability to complete assessment in English; and (6) daily access to the internet (necessary to complete internet-based portions of study, such as at-home surveys and the online daily diary survey).

All participants completed an initial eligibility screening via a brief phone interview with research staff and eligibility was further confirmed at the baseline appointment. Sex criteria were confirmed using the timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview, in which a calendar was used to trigger participants’ recollection of daily sexual behavior (Rendina et al., 2015; Sobell and Sobell, 1992).

Participants were excluded if they demonstrated serious cognitive or psychiatric impairment that would interfere with their participation or ability to provide informed consent, as indicated by a score of 23 or lower on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) or evidence of active and unmanaged symptoms on the psychotic symptoms or suicidality sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-IR (SCID) (First et al., 2002). Cutoffs for the highly sexually active criteria—having a minimum of nine different male sexual partners in the 90 days prior to enrollment, with at least two of these partners being within the prior 30 days—were based off of prior research (Grov et al., 2010b; Parsons et al., 2008; Parsons et al., 2001), including a probability-based sample of urban men who have sex with men (MSM) indicating that nine partners is two to three times the average number of sexual partners among sexually active gay and bisexual men (Stall et al., 2003; Stall et al., 2001).

Participation in the full study required both at-home (Internet-based) and in-office assessments. After eligibility confirmation over the phone, participants received a link to complete an at-home online baseline survey prior to their first in-office appointment. This online survey took approximately one hour to complete. After completion of the baseline survey and appointments, participants completed a prospective daily diary assessment of their affect, daily minority stress, and health behavior for 30 days (Rendina et al., 2015). Each day, at 8pm, participants received an email with a unique link to that day’s online survey. Participants were asked to complete the daily diary survey before going to bed that night, as the link expired at 10am the following day. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

The present study uses data from a sample of 376 men enrolled in the parent study, and relies exclusively on data collected during baseline and the 30-day daily diary period. Five men did not complete any daily diaries, and were therefore unable to be included in analyses. The present study, therefore, focuses on an analytic sample of 371 men. Across these men, sufficient data for the present analyses were collected on a total of 8,275 days—this represents a median of 25 (M = 22.3) days of completion per participant or median adherence of 83.3% (M = 74.3%). Two participants were missing data on employment and are not included in basic frequencies for that variable. Analyses of time-lagged data focus on a subset of 6,769 days’ worth of data for which contiguous data were available to be matched.

Measures

In this study, each participant recorded daily minority stress and daily affect (PA, NA, AA) for the duration of one month. Thus, repeated daily measures exist within participants. Within-person measurements, which fluctuate across days, include two items assessing daily minority stress experiences, as well as the outcome measures of PA, NA, and AA. Between-person measurements, which remain constant across days, include participant demographic characteristics.

Between-participant measures

All participants completed a series of one-time measures as part of an online survey conducted from home prior to the baseline appointment.

Demographics/covariates

Participants were asked to report demographic characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation (gay/queer/homosexual, bisexual), educational level, employment status, income, HIV status (confirmed with an HIV test and with proof of status if positive), and relationship status. The demographic characteristics were assessed using standard pre-defined response options, with the exception of age, which was assessed using a free-response format. For race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, educational level, and income, responses were collapsed into binary measurements to produce meaningful comparisons for the analysis (non-White, White; gay/queer/homosexual, bisexual; less than or greater than 4-year college degree; income less than or greater than $30,000).

Within-participant measures

All participants completed a series of measures on a daily basis as part of the 30-day online daily diary.

Daily Minority Stress

Participants were asked to rank their level of agreement with each of the following statements based on the minority stress model: “Today, I felt good about myself as a gay/bisexual man” (reversed) and “Today, being gay/bisexual stressed me out.” For each statement, participants used a 4-point scale to indicate whether they 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree), or 4 (strongly agree).

Daily Affect

Participants were asked to indicate their daily affective states along PA, NA, and AA dimensions. PA and NA were measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., 1988), which has been previously used in daily diary research (Croft and Walker, 2001; Gable et al., 2000; Mustanski, 2007). AA was measured using a modified PANAS scale (Mustanski, 2007; Watson et al., 1988); AA items were presented together with the PANAS items, a method previously used in research on daily measurements of affect among MSM (Grov et al., 2010a; Mustanski, 2007). The combined scale included a total of 16 items, such as alert, joy, fear, serenity, jittery, and nervous. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they felt each of the items on each day, with response options of 1 (not at all), 2 (a little bit), 3 (quite a bit), and 4 (extremely).

Analyses

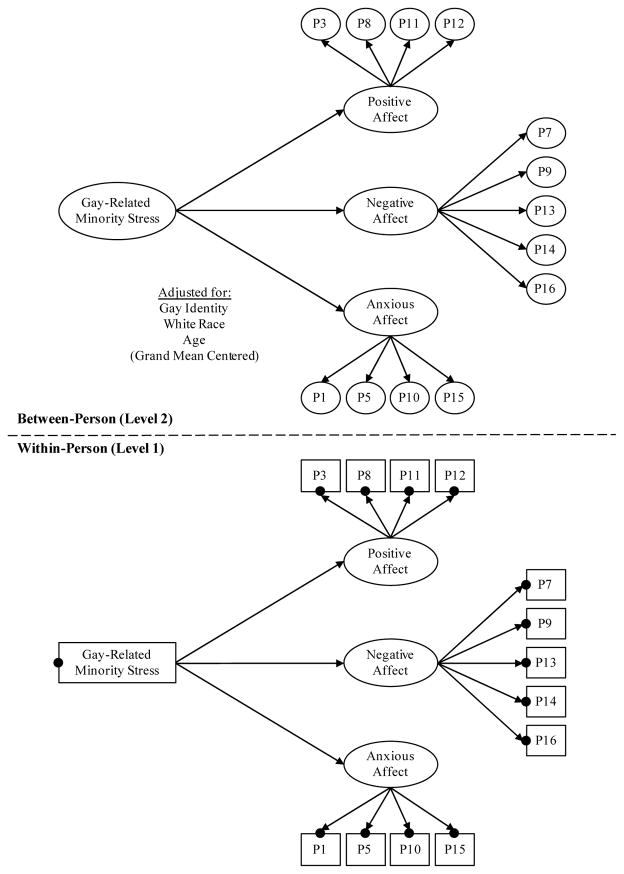

Basic demographic characteristics of the sample were examined. A series of two multilevel structural equation models (MSEMs) utilizing Mplus version 7.31 were then run. The first model (Figure 1), examined the influence of minority stress on experiences of PA, NA, and AA. In the second model, the same analysis was conducted, but with a time-lagged daily minority stress variable predicting PA, NA, and AA on the following day. Across both models, variables measured at the within-person level were disaggregated utilizing latent intercepts into both their fluctuating within-person and stable between-person effects—at the within-person level, minority stress was treated as a manifest (i.e., observed) variable measured as the average of the two minority stress items (grand mean-centered), while PANAS subscales were treated as latent variables measured by their respective manifest items. Both models were adjusted for White race, gay identity, and age (all grand mean-centered) by regressing each latent variable onto the three demographic variables, given that these were the only demographic constructs correlated with the affect outcomes in univariate associations. The Mplus default of robust maximum likelihood (i.e., MLR) estimation was utilized. Results are reported utilizing standardized coefficients.

Figure 1.

The above figure visually depicts the multilevel structural equation model used to predict both within-person and between-person experiences of positive, negative, and anxious affect with daily fluctuations in, and tendencies toward, experiencing gay-related minority stress (measured at the day-level). Black dots at the within-person level represent random intercepts which are then treated as latent variables at the between-person level that differ only across individuals. As can be seen, the same factor structure for the PANAS variables was used at both the within- and between-person levels.

Results

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the 371 participants in the analytic sample. Approximately half were men of color, slightly fewer than half were HIV-positive, and there was good representation of a variety of employment statuses and levels of educational attainment. A majority of the sample was gay-identified and single. About half of the sample had an annual income of less than $30,000. The sample ranged from 18 to 73 years of age, with the mean age being approximately 37 years.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N = 371)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 74 | 19.9 |

| Latino | 50 | 13.5 |

| White | 191 | 51.5 |

| Other/Multiracial | 56 | 15.1 |

| HIV Status | ||

| Negative | 207 | 55.8 |

| Positive | 164 | 44.2 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay, queer, or homosexual | 327 | 88.1 |

| Bisexual | 44 | 11.9 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 117 | 31.5 |

| Part-time | 94 | 25.3 |

| On disability | 49 | 13.3 |

| Student (unemployed) | 31 | 8.4 |

| Unemployed | 78 | 21.0 |

| Highest Educational Attainment | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 42 | 11.3 |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 113 | 30.5 |

| Bachelor’s or other 4-year degree | 124 | 33.4 |

| Graduate degree | 92 | 24.8 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 297 | 80.1 |

| Partnered | 74 | 19.9 |

| M | SD | |

|

|

||

| Age (Range: 18–73; Median = 35.0) | 37.0 | 11.5 |

Note: Two participants were missing data on employment and as a result, percentages do not add up to 100% for this variable.

Results of the initial multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the PANAS revealed some evidence of model misfit (CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90), despite other indicators of adequate fit (RMSEA = 0.04, SRMRWithin = 0.06, SRMRBetween = 0.07), and the model resulted in convergence issues. Examination of the model modification indices provided by Mplus revealed that the largest sources of misfit were a residual covariance between items 4 (scared) and 5 (afraid) on the AA subscale (which resulted in the convergence issues), low primary loading as well as cross-loading of item 2 (sluggish) originally proposed to be on the NA subscale, and low loading of item 6 (alert) on the PA subscale. A modified CFA was then conducted, with results reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the final multilevel confirmatory factor analysis of the PANAS scale

| Item | Within Level

|

Between Level

|

ICC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ | S.E. | λ | S.E. | ||

| Positive Affect Subscale | |||||

| 3. Excited | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| 6. Alert | a | a | a | a | a |

| 8. Determined | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.38 |

| 11. Enthusiastic | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| 12. Inspired | 0.67 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| Negative Affect Subscale | |||||

| 2. Sluggish | b | b | b | b | b |

| 7. Distressed | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 0.39 |

| 9. Upset | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| 13. Discouraged | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.38 |

| 14. Depressed | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.41 |

| 16. Stressed | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Anxious Affect Subscale | |||||

| 1. Jittery | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| 4. Scared | c | c | c | c | c |

| 5. Afraid | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.47 |

| 10. Anxious | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.42 |

| 15. Nervous | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.42 |

Notes. Factor loadings (λ) are presented in standardized form. All results are significant at the p < 0.001 level. ICC = intraclass correlation.

After removing items 2, 4, and 6, the model estimation terminated normally and indices of model fit improved, suggesting adequate to good fit (RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMRWithin = 0.04, SRMRBetween = 0.06). At the within-person level, daily experiences of PA being inversely associated with NA (r = −0.31, p < 0.001) though not AA (r = −0.03, p = 0.32). Daily fluctuations in NA and AA were positively correlated (r = 0.78, p < 0.001). At the between-person level, individuals who tended to experience higher levels of AA also tended to experience greater NA (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) and greater PA (r = 0.12, p = 0.04); PA and NA were uncorrelated (r = 0.00, p = 0.98). The latent factors for PA had greater variance at the within-person level (VarW = 0.26, VarB = 0.20), while the opposite was true for NA (VarW = 0.15, VarB = 0.18) and AA (VarW = 0.06, VarB = 0.12), though all variance estimates were statistically significantly different from zero (p < 0.001). It is worth noting that, despite the high correlation between NA and AA at both the within- and between-person levels, a model in which NA and AA were treated as a single factor had significantly worse fit to the data when comparing the two models (model not shown), Satorra-Bentler Scaled χ2(4) = 917.92, p < 0.001.

Indicators of model fit for the first MLSEM on the same-day association between minority stress and affect were generally good (RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMRWithin = 0.04, SRMRBetween = 0.05). As shown in Table 3, within-person analyses revealed that on days on which participants felt greater minority stress, they experienced lower PA and higher NA and AA. Similarly, at the between-person level, individuals with greater tendencies toward experiencing minority stress experienced lower levels of PA and higher levels of NA and AA. The between-person analyses also revealed that older participants tended to experience lower NA and AA; gay-identified participants, compared to bisexually-identified participants, also tended to experience higher NA and AA; race was not significantly associated with affect in this model. An examination of demographic predictors of the between-person minority stress predictor (not shown in Table 3) demonstrated that younger age and bisexual identity were associated with greater minority stress (β = −0.14, p = 0.006; β = −0.214, p = 0.001, respectively), while no significant association existed for race (β = −0.06, p = 0.22). Results revealed an ICC of 0.68 for the daily measure of gay-related minority stress, suggesting that a large proportion of its variance arises from between-person rather than within-person differences. For the affect items, results indicated an ICC range of 0.31 to 0.47 (M = 0.40), suggesting that the largest portion of variance among affect measures arises from within-person differences rather than between-person differences. Overall, the models predicted the greatest amount of variation in between-person NA and AA, and the least amount of variation in within- and between-person PA.

Table 3.

Results of two multilevel structural equation models examining the role of gay-related minority stress on daily affect

| Same-Day Model

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect

|

Negative Affect

|

Anxious Affect

|

|||||||

| β | S.E. | p | β | S.E. | p | β | S.E. | p | |

| Within-Person Level | |||||||||

| Gay-Related Minority Stress | −0.19 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Latent Outcome R2 | 0.04 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 | < 0.001 |

| Between-Person Level | |||||||||

| Gay-Related Minority Stress | −0.22 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.33 | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.50 | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.002 | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Gay Identity | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.003 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.008 |

| White Race | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.63 |

| Latent Outcome R2 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Time-Lagged Model

|

|||||||||

| Next Day’s Positive Affect

|

Next Day’s Negative Affect

|

Next Day’s Anxious Affect

|

|||||||

| β | S.E. | p | β | S.E. | p | β | S.E. | p | |

| Within-Person Level | |||||||||

| Gay-Related Minority Stress | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Latent Outcome R2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| Between-Person Level | |||||||||

| Gay-Related Minority Stress | −0.21 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.34 | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.50 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.004 | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Gay Identity | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.007 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| White Race | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.65 |

| Latent Outcome R2 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

Note. Model results are presented in standardized form.

The second model sought to determine whether within-person effects of minority stress on affect would carry over into the following day. The between-person portion of the model was consistent with that in the first model and the within-person outcome consisted of minority stress variables from any given day predicting affect variables on the next. Overall, model fit was similar to the same-day model (RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMRWithin = 0.04, SRMRBetween = 0.05). Results were statistically significant and consistent in direction. Given the lapse in time between the experience of minority stress and the report of affect, results were unsurprisingly diminished in magnitude compared to the same-day model.

Discussion

This study found that daily self-reported experiences of minority stress are associated with daily negative affect (NA) and anxious affect (AA) and negatively associated with daily positive affect (PA), both concurrently and in lagged analyses, in a highly sexually active sample of gay and bisexual men. These findings indicate that minority stress and affect can be conceptualized as time-varying constructs that demonstrate significant associations with each other across days. These results extend previous cross-sectional research showing that minority stress measured as global tendencies is associated with depression and anxiety, as well as several other mental health problems (D’Amico and Julien, 2012; Feinstein et al., 2012; Mays and Cochran, 2001; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Newcomb and Mustanski, 2010; Potoczniak et al., 2007). The current results demonstrate that minority stress also fluctuates over time and predicts the time-varying primary domains of emotional structure (i.e., PA, NA, and AA) that have been consistently linked to major depressive and anxiety disorders.

The present study also found support for greater between-person than within-person variation in minority stress, suggesting that while minority stress fluctuates across days, minority stress might be best conceptualized as a characteristic experience of certain individuals. Whether this stable trait-like experience reflects a tendency for some gay and bisexual men to accrue more minority stress experiences than others or a reporting style whereby some gay and bisexual men report more minority stress experiences than others merits further examination. However, minority stress, when modeled as both a stable trait-like between-person construct and a time-varying experience, predicted higher NA and AA and lower PA across participants. This result is the first known to suggest that daily measurement of minority stress can compliment trait-level assessments, but also indicates that the current, increasingly vast literature on minority stress conceptualized cross-sectionally is also valid. This study’s results suggest a novel measurement approach and also innovatively validate the cross-sectional measurement approach adopted in previous studies of minority stress (e.g., Feinstein et al., 2012; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Mays and Cochran, 2001; Newcomb and Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis et al., 2015).

The time-lagged analysis revealed that minority stress experienced on a given day positively predicts NA and AA and negatively predicts PA on the following day, yielding preliminary support for a causal relationship between minority stress and affective disruptions. Previous research on rumination and minority stress supports this pattern of findings. Rumination, a defining feature of poor affect regulation, refers to a passive and repetitive focus on one’s distress and related circumstances. Preliminary evidence suggests that gay and bisexual men are disproportionately likely to ruminate compared to heterosexuals (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008) and that rumination is associated with experiences of minority stress (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). The fact that rumination exacerbates and maintains NA and AA and lower PA over time (McLaughlin et al., 2007) substantiates the present study’s finding that minority stress predicts NA, AA, and PA on subsequent days. Although daily rumination was not measured in the present study, previous experimental research indicates that sexual minority participants who ruminate upon recalling a personal discriminatory event exhibit prolonged distress compared to participants who do not ruminate (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). Thus, future investigations into time-lagged associations between minority stress and affect should include measures of possible mediators of the minority stress-affect relationship, including rumination.

This study contributes to the small but growing body of research that examines sexual minority individuals’ daily experience. Whereas two previous daily diary studies of sexual minority individuals have found relationships between stigma-related experiences and psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009) and sexual orientation disclosure and subjective well-being (Beals et al., 2009), no known study has examined the time-lagged associations between minority stress and affective experiences across 30 days. Time-lagged analyses come closer than analyses of concurrent associations to establishing a causal role of minority stress in the prediction of affect, although an experimental design would be capable of more definitively establishing the direction of this effect. Further, the use of a 30-day assessment period extends related work that has been limited to shorter assessment periods (e.g., Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler, 2013; Pachankis et al., 2011).

Results of this study must be interpreted in light of its limitations. The sampling approach represents a methodological strength, yet poses a challenge to generalizability. Specifically, while the sample is composed of substantial diversity in terms of race and ethnicity, age, SES, and HIV status, participants were, by design, also highly sexually active and lived in New York City. Future daily diary studies of minority stress and affect should enroll a nationally representative sample, which would allow for a more complete examination of moderating factors, including the impact of demographic factors and geographic location on the effects uncovered here. Further, the self-report nature of this study’s measurements might have yielded biased estimates, given the known confounds between mental health status and reports of stress (Dohrenwend, 2006; Meyer, 2003a). Additionally, the measure of daily minority stress used here was created for this study and is in need of further validation in studies using diverse sexual minority samples and conjointly administered daily measures capable of establishing the scale’s construct validity. Lastly, the measure of daily minority stress used here best represents the minority stress processes of internalized homophobia and rejection sensitivity, yet does not represent discrimination or sexual orientation concealment; as such, results from this study may have limited generalizability to broader operationalizations of minority stress, and future measurements of minority stress should assess all core processes of minority stress.

While this study demonstrates a more nuanced association between minority stress and affect than currently exists, the complex interplay between minority stress, affect, and health outcomes should be explored in future studies. Minority stress has been implicated in the syndemic surrounding gay and bisexual men’s health (e.g., Pachankis, 2015; Parsons et al., 2012; Parsons et al., 2015b; Stall et al., 2008). Previous work has also indicated that various domains of state affect might contribute to some of gay and bisexual men’s syndemic conditions (Bousman et al., 2009; Grov et al., 2010a; Mustanski, 2007). Therefore, delineating the mechanisms through which sexual minority stress and affect contribute to this phenomenon is essential to addressing the health concerns of sexual minority men.

The findings of this study also have implications for the elimination of sexual orientation-based mental health disparities. Eliminating health disparities must be a priority of future national and international public health initiatives. At the distal level, institutional policy change that seeks to create more favorable social climates for sexual minorities, such as the repeal of laws oppressive to sexual minorities and the passage of laws that protect their rights, may be effective in reducing minority stress in these populations, and therefore a most effective method for reducing sexual orientation-related health disparities. At the proximal level, clinical interventions for the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders among gay and bisexual men could employ therapies aimed at developing healthy coping strategies to deal with minority stress (e.g., Cook et al., 2014; Miller and Kaiser, 2001; Pachankis, 2014). Combined with upstream changes that reduce the prevalence of minority stress exposure, individual-level interventions that empower sexual minority men to cope with the emotional effects of minority stress have the potential to yield a lasting impact on the reduction of mental health disparities, and ultimately reduce co-occurring adverse health conditions among gay and bisexual men. Results of this study suggest that delivering coping interventions to those men at greatest risk of experiencing minority stress would be an effective use of limited public health resources.

Highlights.

We examine the association between daily minority stress and daily affect among gay/bisexual men. Daily minority stress significantly predicts same-day and subsequent-day affect. Minority stress temporally effects daily affect. Minority stress contributes to daily fluctuations in affect among gay/bisexual men.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH087714; Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). Jonathon Rendina was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01-DA039030; H. Jonathon Rendina, Principal Investigator). The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Pillow Talk Research Team: Brian Mustanski, Ruben Jimenez, Demetria Cain, and Sitaji Gurung. We would also like to thank the CHEST staff who played important roles in the implementation of the project: Chris Hietikko, Chloe Mirzayi, Anita Viswanath, Arjee Restar, and Thomas Whitfield, as well as our team of recruiters and interns. We are grateful to Marney White for providing helpful feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. Finally, we thank Chris Ryan, Daniel Nardicio and the participants who volunteered their time for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beals KP, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousman CA, Cherner M, Ake C, Letendre S, Atkinson JH, Patterson TL, Grant I, Everall IP, Group H. Negative mood and sexual behavior among non-monogamous men who have sex with men in the context of methamphetamine and HIV. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, Busch JT. Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft GP, Walker AE. Are the Monday blues all in the mind? The role of expectancy in the subjective experience of mood. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;31:1133–1145. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E, Julien D. Disclosure of sexual orientation and gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ adjustment: Associations with past and current parental acceptance and rejection. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2012;8:215–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:917–927. doi: 10.1037/a0029425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York Stat Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN) [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Reis HT, Elliot AJ. Behavioral activation and inhibition in everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:1135–1149. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Mustanski B, Parsons JT. Sexual compulsivity, state affect, and sexual risk behavior in a daily diary study of gay and bisexual men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010a;24:487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0020527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2010b;39:940–949. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Kupprat SA, Hampton MB, Perez-Figueroa R, Kingdon M, Eddy JA, Ompad DC. Evidence for a syndemic in aging HIV-positive gay, bisexual, and other MSM: Implications for a holistic approach to prevention and healthcare. Nat Resour Model. 2012;36(2) doi: 10.1111/napa.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly JB, Dyck MJ, Kramer TA, Wherry JN. Integration of positive and negative affectivity and cognitive content-specificity: Improved discrimination of anxious and depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:544–552. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher K. Assessing subjective well-being in the old-old: The PANAS as a measure of orthogonal dimensions of positive and negative affect. Res Aging. 1992;14:131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behav Ther. 2007;38:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1477–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. Am J Public Health. 2003a;93:262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003b;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Kaiser CR. A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang YJ, Moskowitz JT, Catania JA. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:278–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. The influence of state and trait affect on HIV risk behaviors: A daily diary study of MSM. Health Psychol. 2007;26:618–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clin Psychol – Sci Pr. 2014;21(4):313–330. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Arch Sex Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML. The social development of contingent self-worth in sexual minority young men: An empirical investigation of the “Best Little Boy in the World” hypothesis. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2013;35:176–190. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ. The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. A minority stress-emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychol. 2015;34:829–840. doi: 10.1037/hea0000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR. The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:142–152. doi: 10.1037/a0022917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Bimbi D, Halkitis P. Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the internet. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention. 2001;8(2):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:156–162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, DiMaria L, Wainberg ML, Morgenstern J. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:817–826. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Cook KF, Grov C, Mustanski B. A psychometric investigation of the hypersexual disorder screening inventory among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: An item response theory analysis. J Sex Med. 2013;10:3088–3101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Moody RL, Grov C. Hypersexual, Sexually Compulsive, or Just Highly Sexually Active? Investigating Three Distinct Groups of Gay and Bisexual Men and Their Profiles of HIV-Related Sexual Risk. AIDS Behav. 2015a:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, Grov C. Syndemic production and sexual compulsivity/hypersexuality in highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: Further evidence for a three group conceptualization. Arch Sex Behav. 2015b:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potoczniak DJ, Aldea MA, DeBlaere C. Ego identity, social anxiety, social support, and self-concealment in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54:447. [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. Aggregate and event-level associations between substance use and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: Comparing retrospective and prospective data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline Follow-Back. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Friedman M, Catania JA. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, Catania JA. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, Mills TC, Binson D, Coates TJ, Catania JA. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, O’Donnell K, Marmot M, Wardle J. Positive affect and psychosocial processes related to health. Br J Psychol. 2008;99:211–227. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2008.tb00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventuneac A, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Mustanski B, Parsons JT. An item response theory analysis of the sexual compulsivity scale and its correspondence with the hypersexual disorder screening inventory among a sample of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. J Sex Med. 2015;12:481–493. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Intraindividual and interindividual analyses of positive and negative affect: Their relation to health complaints, perceived stress, and daily activities. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1020–1030. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:3. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]