Abstract

Objective

Item response theory (IRT) and computerized adaptive testing (CAT) methods allow the development of a large calibrated item bank from which different subsets of questions can be selected for administration and scored on a common scale. Our objective was to develop an outpatient rehabilitation self-report short form for the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care Applied Cognition item bank.

Design

Using data from a convenience sample of 235 rehabilitation outpatients, item content and IRT-based test information function parameters were employed in item selection. Internal consistency reliability, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and percent at the lowest (floor) and highest (ceiling) scores were evaluated for the short form and full item bank.

Results

A 15-item short form was developed. The internal consistency of the short form was 0.86. The ICC3,1 for the short form and item bank was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94, 0.98). No floor effects were noted, and ceiling effects were 27.66 % (short form) and 26.38% (full item bank).

Conclusions

The Applied Cognition outpatient short form demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties and provides a bridge to IRT-based measurement for settings where point of care computing is not available.

Keywords: Outcome Assessment, Rehabilitation, Item Response Theory, Cognition, Cognition Disorders, Psychomotor Performance, Questionnaires, Psychometrics

INTRODUCTION

Improved outcome measurement for post-acute rehabilitation has been recognized as a fundamental requirement for the advancement of the evidence base for clinical decision-making and health care policy.1 Because conditions requiring post-acute care (PAC) often have cognitive as well as physical impacts, most contemporary functional instruments address cognitive functional skills to some extent. Evidence indicates that cognition is an important contributor to performance of instrumental activities of daily living and should be measured as a separate dimension of function in rehabilitation.2–5 Existing instruments consist largely of clinician-reported or performance-based tests with varied content covering skills such as receptive and expressive communication, problem solving, and memory.2 However, measures have not been developed based on a clear conceptual framework and in-depth empirical testing, which has led to the identification of the need for stronger measures of cognitive function for post-acute care.1 This research project focuses on the measurement of applied cognition, which represents “discrete functional activities whose performance depends most critically on application of cognitive skills, with limited movement requirements.”2

The Activity Measure for Post-acute Care (AM-PAC) was developed using the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability (ICF) to inform content coverage and extensive empirical testing to validate three main functional dimensions: Basic Mobility, Daily Activities, and Applied Cognition.6,7 The development of the Applied Cognition scale addressed limitations in the precision and content coverage of widely used instruments addressing cognition in PAC settings such as the FIM,8 Minimum Data-Set-Post-Acute Care (MDS-PAC)9 and Outcome Assessment and Information Set (OASIS).10

The AM-PAC was developed using Item Response Theory (IRT) methods, which provided evidence for a unidimensional scale consisting of a comprehensive set of items addressing low to high cognitive functioning. Since each item was calibrated on one underlying scale, it can be administered using Computerized Adaptive Test (CAT) methods, which leverage IRT to tailor question selection in real time based on the respondent’s answers to the preceding questions. Therefore, only a small number of questions need to be answered and test scores from these individualized administrations are scored on a common scale generated from the calibrated item bank. Because scores are comparable across patients and over time, IRT-based measurement including CAT instruments provides a practical means for monitoring health outcomes with precision across a wide range of ability levels and settings, and over time.11,12

CAT administration requires point-of-care computing access within the care setting. For many PAC settings this capacity is not yet available. As an alternative, IRT methods have been applied to create customized short forms selected from the calibrated item bank that allow paper-and pencil or other fixed administration.13 This approach enables comparison of scores from different short forms and CAT instruments based on the same item bank in settings requiring more traditional administration methods.13

In earlier work, short forms were developed for each of the original AM-PAC scales.14 Subsequently a larger calibration study was conducted to expand and refine the AM-PAC instrument, and new short forms were developed for the Basic Mobility and Daily Activities scales for outpatient rehabilitation.15 The aims of the current project were to create an outpatient rehabilitation short form for the expanded Applied Cognition scale and to conduct an initial assessment of its measurement properties. It was expected that the AM-PAC Applied Cognition outpatient short form would cover an adequate score range and achieve a high level of agreement with the full item bank and acceptable reliability and respondent burden.

METHODS

Background: Development of the AM-PAC Item Banks and the AM-PAC-CAT

Development of the 3 AM-PAC item banks and CATs has been described elsewhere.2,6,16 The final item bank for the Basic Mobility domain includes 131 items and the Daily Activities item bank consists of 88 items representing the domain of personal care and instrumental activities.17,18 The questions ask either how much difficulty the respondent has or how much help the respondent needs to do specific activities. The development of the AM-PAC Applied Cognition item bank paralleled that of the Basic Mobility and Daily Activities item banks.2,6,16 The calibration field study was conducted in 2 phases, using the combined data from the total convenience sample of 1035 adults participating in rehabilitation for a range of clinical conditions, including neurologic (e.g. stroke, brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis), medically complex (e.g. post-surgical and cardiopulmonary conditions), and musculoskeletal (fractures and orthopedic surgeries such as joint replacement).16 Data were collected in acute rehabilitation, skilled nursing, outpatient and home care rehabilitation settings by trained interviewers within six regional rehabilitation networks. The institutional review board of the university and human subjects protection committees of all participating facilities approved the study protocol.

IRT analyses supported the final unidimensional scale consisting of 50 items addressing applied cognition with difficulty estimates ranging from −3.34 to 3.24 logits. Item content in the Applied Cognition item bank includes such activities as reading, managing daily routines, using the telephone, communicating, managing money, and problem-solving.

DIF Analyses

For items fitting the IRT model, responses to an item should be determined by the difficulty level of the item and the functional/ability level of the respondent. If responses differ based on other variables such as age or gender, the item is characterized as exhibiting differential item functioning (DIF). Before conducting item selection analyses for this project, differential item functioning (DIF) was investigated using the entire sample of 1035 patients based on background variables including age, gender, patient condition group (neurological, medically complex, and musculoskeletal) and rehabilitation setting (acute rehabilitation, skilled nursing, outpatient, and home care).

Ordinal logistic regression was used to examine DIF. Two ordinal logistic regression models were fit for each item. The first model included the summary score as the independent variable and the item response as the dependent variable. The second model added the background variable of interest and the interaction between the background variable and summary score as the independent variables. Any item with R-square change greater than 0.02 between the two models was identified as exhibiting DIF.19

Subjects and Analysis

Data Collection Procedures

To create the Applied Cognition short form, response data for the Applied Cognition item bank were used from the outpatient sample of 235 outpatient rehabilitation patients with neurological, medically complex, and musculoskeletal conditions in the calibration field study.7

Short Form Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographic variables including means, standard deviations, and proportions as appropriate. The severity of patients’ impairments was classified using the modified Rankin scale,16,20 which consists of 5 disability levels from none to bedridden. Because very few patients were in the lowest and highest categories, the lowest and the highest 2 categories were combined. Therefore, “Slight Disability” included those with no symptoms and those who were ‘unable to carry out all previous activities but able to look after own affairs without assistance.’ “Moderate Disability” included those ‘requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance,’ and “Severe” included the categories ‘unable to walk without assistance, and unable to attend own bodily needs without assistance’ and ‘bedridden.’

Item Selection Criteria

Item selection for short forms requires consideration of multiple factors,21 including measurement precision, content relevance, content coverage, and score range.14,15,21,22 The target population was outpatient rehabilitation patients. Because of the wide range of cognitive function exhibited in this population without clear evidence of condition-based content or difficulty thresholds, one short form that could be used across community populations was developed. Therefore the aim was to cover the range of the continuum and to strike a balance between the need for high quality measurement and to minimize the data collection burden for patients and clinicians. The following criteria were used to select items from the AM-PAC Applied Cognition item bank for inclusion in the short form: item information, range of score coverage, and item functional content.15

Item Information and Score Range

The item characteristic curve is a representation of the probabilities associated with endorsement of each response to an item.23 Based on the item characteristic curve, the item information function characterizes the amount of precision with which an item can estimate the functional level of the subject, and can be used to calculate a value for the information provided by each item. Item information values can be summed across all of the items to form test information functions (TIFs).24 A TIF for a specific set of items shows graphically the precision levels for an item set relative to functional level (person ability scores) for a sample. The overall approach was to select a set of items matched to the score distribution for the outpatient sample using item information and test information.25 The analytic steps are described in detail below. First, the criterion for acceptable reliability for the short form was set at greater than or equal to 0.80. Using the known score variance from the sample the target test information value () of the short form that would be required to achieve the target reliability of 0.80 was calculated. To select items with information matched to the score range of the sample, the test information function was weighted by the outpatient sample distribution using the formula: I = ∫ info(θ)g(θ)dθ, I. The item selection process aims to choose the set of items that maximizes the value of I. Although this formula incorporates both test information, (info(θ)), and the sample score distribution into the selection process, it does not preclude selection of items with very high information values that cover a narrow score range. To limit this possibility, the highest test information value for any candidate set of items was constrained to that of the target information value. This ensured the selection of items that maximized both the test information and coverage across the score range. In order to test this procedure, the short form item selection process was repeated without constraining the target information value. Then reliability, ceiling and floor effects, and test information function were compared for the unconstrained short form and the final short form.

To select the items from the item bank, the information value (I) for each item was calculated. The item with the highest information value was selected first. Then the information value was calculated for each candidate 2-item short form to include that included the first selected item combined with each candidate item. The 2-item short form with highest value of I was identified, and the second item was selected from that short form. This process was repeated N times (N is the maximum possible number of items in the short form) to obtain a series of short forms (the number of items varied from 1 to N). To determine number of items in the final short form, the internal consistency reliability of short forms with 1 to N items was examined, and the item content coverage was assessed, as described below.

Simulation methods were employed to estimate the IRT-based internal consistency reliability for the short forms and the full item bank. First, 30,000 response patterns were generated by sampling from the empirical person score distribution of the full item bank, and then the squared correlation between IRT score estimates and the true scores were calculated.26

Item Functional content

Considered was given to the content coverage of the selected items with the goal of representing the range of community-relevant functional tasks in the Applied Cognition item bank and avoiding overrepresentation of a particular task (for example, remembering).

Assessment of Measurement Properties

To assess the measurement properties of the short form, score range, reliability and accuracy were evaluated, as described below.

Score Range

Descriptive statistics were calculated for average item difficulty and the range of scores for the short form. The test information functions of the short form and the item bank were compared to the score range of the sample. To evaluate potential problems in measurement across the range of function of the sample population the percent of subjects who received the lowest possible score (the floor) and the percent of subjects who received the highest possible score (the ceiling) were calculated for the short form and the item bank. To explore the score range by impairment group, post-hoc Tukey-Kramer tests were conducted to detect differences in mean score for the full item bank and short forms by impairment group.

Reliability

The internal consistency reliability of the final short form was assessed based on the procedures described above. The conditional reliability of the short form and the full item bank were compared across multiple functional levels of the scale, measured as: (Score variance-1/information value)/score variance.27

Accuracy

The accuracy of the short form was addressed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC3,1) and the 95% confidence interval for agreement between the short form scores and full item bank scores. The score agreement between the short form and full item bank was also examined using the Bland-Altman plot.28

RESULTS

DIF Analyses

Our analyses revealed some items within the scale that demonstrated DIF. The item, “understanding information on food labels,” exhibited DIF across age, and, coping with unexpected daily events,” “using information on the bill to figure out where to call if you have a problem,” and keeping important personal papers such as bills, insurance documents and tax forms organized” exhibited DIF across patient group (neurological, orthopaedic, medically complex). In addition, 2 items “remembering things such as steps to complete daily activities, people's names, etc.” and “taking care of complicated tasks like managing a checking account or getting appliances fixed” demonstrated DIF across rehabilitation settings. These 6 items were removed from the item bank before analyses were conducted on the outpatient sample.

Subject Characteristics

The characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 56 years (S.D. 17), and 52% were female. The majority of the sample was white, and a wide range of educational levels was represented. The severity of disability was characterized as slight in 51.5%; moderate in 40%; and severe in 7% of the sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample: 235 outpatient rehabilitation patients

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age: Mean(SD) | 56.15(16.67) |

| ≥80 years | 19(8.15) |

| ≥70 | 31(13.3) |

| ≥60 | 48(20.6) |

| ≥50 | 55(23.61) |

| ≥40 | 43(18.45) |

| <40 | 37(15.88) |

| missing | 2 |

| Gender (female) | 123(52.34%) |

| Race | |

| White | 203(86.38%) |

| Black | 26(11.06%) |

| Other | 6(2.55%) |

| Education level | |

| 8th grades or fewer | 3(1.28%) |

| Some high school | 14(5.96%) |

| High school/GED | 63(26.81%) |

| Some college/2 years degree | 65(27.66%) |

| 4 years college | 46(19.57%) |

| >4 years college | 43(18.30%) |

| Missing | 1(0.43%) |

| Impairment Group | |

| Neurological | 97 |

| Medically complex | 39 |

| Orthopaedic | 99 |

| Severity of Disability* | |

| Severe | 17(7.23%) |

| Moderate | 93(39.57%) |

| Slight | 121(51.49%) |

| Missing | 4(1.7%) |

Based on an adapted Modified Rankin Scale20

Applied Cognition Short Form

Logit scores were transformed to T scores with mean = 50; standard deviation = 10, with higher scores indicating better function. The score variance of the outpatient sample was 2.91; therefore, the target information value in our sample is 1.72. The maximum number of items in the short form was set at 20; therefore, the item selection process resulted in 20 short forms (number of items from 1 to 20). To determine the number of items in the final short form, the internal consistency reliability of short forms with 1 to 20 items and the item content were examined. When the number of items was equal to 7, the reliability of the short form was 0.8. When the number of items was greater than 13, the reliability exceeded 0.85. Taking into consideration the reliability, respondent burden, and item content coverage, the final short form included 15 items covering content such as understanding and communicating directly and using the telephone; remembering; managing activities; reading; following instructions; and completing complicated tasks (Table 2). Because the initial 15 items represented a range of community-relevant functional tasks no changes were made based on functional content. All items fit the model and average item difficulty ranged from 29.16 to 42.42.

Table 2.

Item content, range of coverage, INFIT and item difficulty of the Applied Cognition Short Form

| Applied Cognition Short Form Item Content | Item Difficulty |

INFIT (MNSQ) |

Score Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| getting to know new people | 29.16 | 1.30 | 13.09~47.65 |

| managing your time to do most of your daily activities | 32.20 | 1.15 | 19.26~46.42 |

| carrying on a conversation with a familiar person in a noisy environment (e.g., a large social group) | 32.38 | 1.18 | 16.17~48.27 |

| remembering to take medications at the appropriate time | 32.49 | 1.10 | 20.49~47.04 |

| following/understanding a 10 to 15 minute speech or presentation (e.g. lesson at a place of worship, guest lecture at a senior center) | 32.81 | 1.11 | 19.88~47.65 |

| remembering where things were placed or put away (e.g., keys) | 33.23 | 1.35 | 11.85~55.68 |

| planning for and keeping appointments that are not part of your weekly routine (e.g., a therapy, doctor appointment, or a social gathering with friends and family | 34.30 | 1.11 | 21.73~48.89 |

| checking the accuracy of financial documents, (e.g., bills, checkbook, or bank statements) | 37.73 | 0.74 | 29.14~47.65 |

| reading and following complex instructions (e.g., directions to operate a new appliance or for a new medication) | 38.04 | 1.08 | 24.81~53.21 |

| following a recipe to make a new dish (e.g., a new pie or soup recipe) | 38.31 | 1.25 | 29.75~47.65 |

| using a local street map to locate a new store or doctor's office | 38.57 | 1.29 | 29.75~48.89 |

| reading a long book (over 100 pages) over a number of days | 39.40 | 1.20 | 27.9~51.36 |

| filling out a long form (e.g., insurance forms or an application for services) | 40.46 | 1.14 | 29.75~53.21 |

| doing calculations in your head while shopping (e.g., 30% off, etc.) | 40.80 | 1.5 | 30.37~53.21 |

| remembering a list of 4 or 5 errands without writing it down | 42.42 | 1.29 | 27.90~61.23 |

The item goodness of fit was assessed by Infit Mean Square (MNSQ) residual. We adopted Bond and Fox's criteria and considered 0.6–1.4 an acceptable Infit MNSQ range.31

Measurement Characteristics

Score Range

The entire range of scores for the short form was from 11.85 to 61.23 (mean 50; SD 10). None of the subjects were at the floor for either the short form or the item bank. For the short form and the item bank respectively, there were 65 subjects (27.66%) and 62 subjects (26.38%) at the ceiling score. Table 3 provides a summary table of descriptive statistics for score range. The largest proportion of patients at the ceiling was in the group with musculoskeletal conditions, followed by those with medically complex and neurological conditions. Post-hoc Tukey-Kramer tests for differences across impairment groups revealed significant differences in mean scores for the full item bank item across all groups F(2,232)=23.48, p<0.0001. Mean short form scores were different between neurological and orthopaedic groups: F(2,232)=18.36, p<0.0001. The mean short form score for the medically complex group was not significantly different from that of the other two groups.

Table 3.

Percent with highest score (ceiling) of the Applied Cognition Scale by impairment group.

| Subjects n |

Short Form (15 items) |

Full Item Bank (44 items) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Score (SD) |

Floor n(%) |

Ceiling n(%) |

Mean score (SD) |

Floor n(%) |

Ceiling n(%) |

||

| Outpatient | 235 | 0 | 65(27.7) | 0 | 62(26.4) | ||

| Neurological | 97 | 47.2(10.1) | 0 | 14(14.4) | 47.5(10.2) | 0 | 12(12.4) |

| Medically Complex | 39 | 51(9.2) | 0 | 12(30.8) | 52.6(10.1) | 0 | 12(30.8) |

| Orthopaedic | 99 | 55.1(8.3) | 0 | 39(39.4) | 56.9(8.8) | 0 | 38(38.4) |

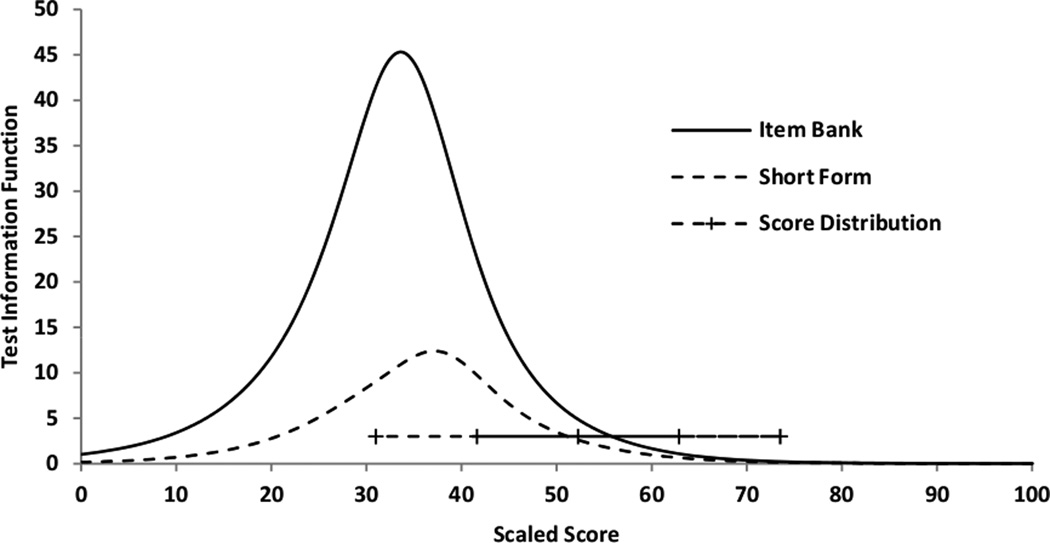

Figure 1 shows the comparison between the test information functions for the short form and the full item bank, and demonstrates the increase in precision associated with the larger number of items in the full item bank. The peaks of the TIF plots for the short form and the full item bank approached the score range where most of the subjects were located, but were shifted toward lower function.

Figure 1.

Test information function for the Applied Cognition Short Form and the Full Item Bank

“+” represents the mean, 1SD, 2SD of the score distribution

Reliability

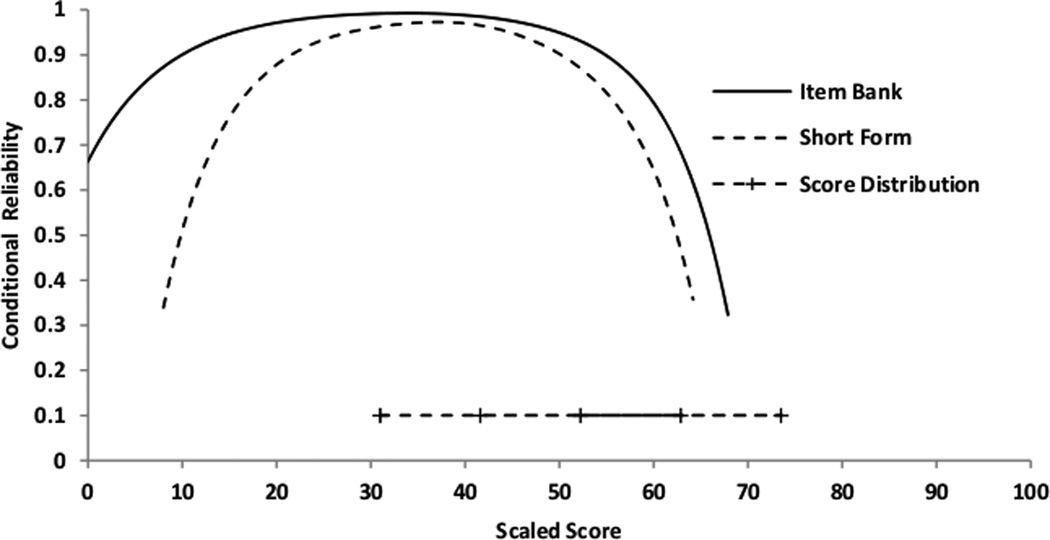

The short form demonstrated reliability greater than 0.80 in the score range from 17~56, and more limited performance for scores beyond 56 (Figure 2). The IRT-based internal consistency reliability of the short form was 0.86, which is comparable to that of the full item bank (0.89).

Figure 2.

Conditional Reliability of the Applied Cognition Short Form and the Full Item Bank

“+” represents the mean, 1SD, 2SD of the score distribution

Accuracy

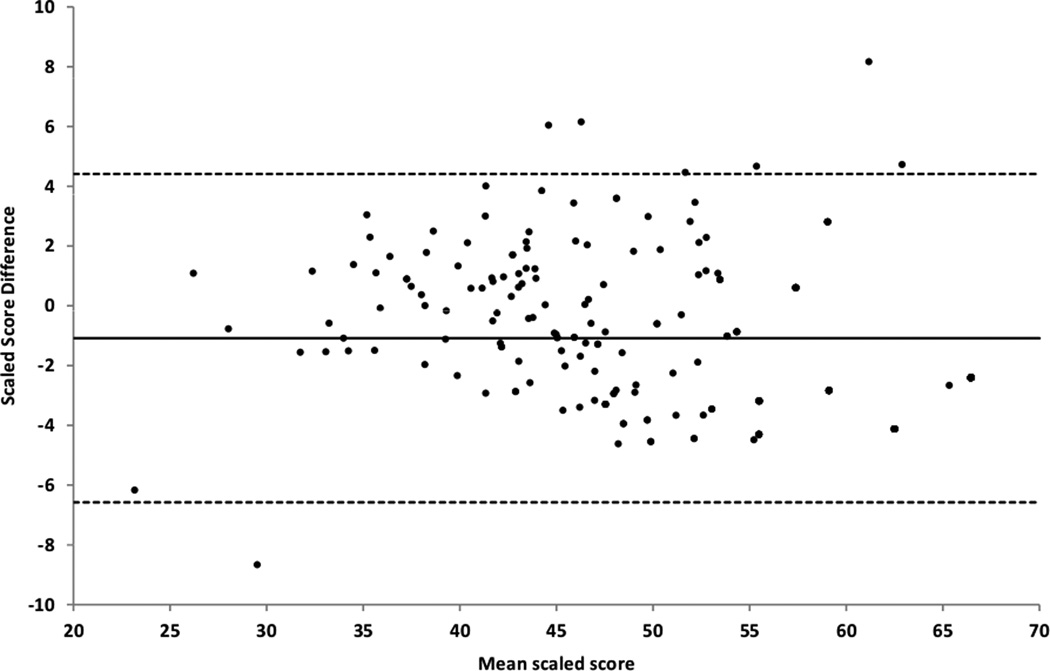

The intraclass correlation of the short form scores with full item bank scores was ICC3,1: 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94, 0.98), which indicates very strong agreement. The Bland-Altman plot demonstrates that most of the score differences were within the 95% limits of agreement (Figure 3). The variation in score difference increased as the average score increased, which is reflected in the decreasing reliability of the short form as the scores increased.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plot for scores based on the short form and the full item bank

The x-axis represents the average of the short form score and full item bank score. The y-axis represents the difference between short form score and full item bank score. The solid line is the mean difference between the short form based scores and full item bank based scores.

The two dash lines indicate the 95% limits of agreement.

The results of the test of our item selection method with the alternative approach in which the target information value was not constrained revealed that there were 8 items (53%) in common across the two short forms using the two approaches. The internal consistency reliability of the short form using the unconstrained approach was 0.84, which is less than the final short form (0.86). The ceiling and floor effects of short form based on the unconstrained approach were 79 (33.62%) and 1(0.43%) respectively, which were worse than those in final short form (27.66%, 0%). As expected, the test information function of the short form selected using the unconstrained approach resulted in a higher test information value and less score coverage compared with the final short form (See Supplemental Digital Content: Appendix A).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that a 15-item short form for the AM-PAC Applied Cognition domain demonstrated acceptable score range coverage, accuracy and reliability for measurement of self-reported cognitive functioning in outpatient community rehabilitation settings. The final short form demonstrated high reliability and score agreement with the full item bank.

Our goal was to develop an instrument that may be used across patient groups. Therefore, analyses were conducted to evaluate differential item functioning across impairment groups and background variables. After removing 6 items from the item bank that exhibited DIF, our results indicated that the remaining 44 items in the item bank function consistently regardless of impairment category, and therefore can be used across people with these impairments. Indeed our aim in developing the measure was to be able to detect differences in functioning for people within and across different conditions. Differences were found in score distributions by impairment group, with lower scores noted for people with neurological conditions than those with medically complex or musculoskeletal conditions. This is not surprising since neurological conditions are more likely to be associated with cognitive sequelae than musculoskeletal conditions.

As expected, ceiling effects were found for this short form. To maximize generalizability, the sample included persons with a range of conditions, some of which have less impact on cognitive function. Because the short form was not developed exclusively for a subset of conditions such as for persons with neurological disorders, a proportion of our sample would be expected to have minimal or no cognitive impairment, and therefore be correctly characterized at the ceiling. The lowest ceiling effects were found for patients with neurological disorders, and highest effects were found for patients with musculoskeletal problems. We acknowledge that this short form will be of greatest use among patient groups with cognitive difficulties. Although lower ceiling effects would be advantageous, as we have reported previously there is no obvious set of more difficult items that are not confounded by education.2

Evidence supports the need to measure cognitive function as a separate, important dimension of outcome for people undergoing rehabilitation.2–5 The Applied Cognition outpatient short form can be used to assess aspects of cognitive and communication skills that are critical to rehabilitation outcomes and living in the community for people with cognitive impairments, such as the ability to remember appointments and everyday tasks; to follow conversations; plan their day, manage medications and to way-find in the community. The fact that the Applied Cognition items fit the IRT model supports the interpretation of scores at the interval level. Therefore the magnitude of score change can be interpreted similarly across the range of the scale, regardless of the specific items used to assess function – a 10 point change at the low end of the scale indicates a similar change in ability as a 10 point change at the higher end. The scoring on a scale with mean=50; standard deviation of 10 provides context for a patient or group of patients’ scores relative to the larger distribution, such that 10 points indicates a large difference or change. The AM-PAC is copyrighted by the Trustees of Boston University. AM-PAC short forms can be licensed for $280/year. License information and a scoring table for the AM-PAC Applied Cognition outpatient short form is available from the authors.

Our findings build on earlier work demonstrating the usefulness of IRT methods to guide item selection for short forms tailored to user needs (e.g. outpatient versus inpatient) that allow score comparison to other short forms and CAT scores derived from the same calibrated item bank. Traditional functional measures were developed independently for each post-acute care setting and, consequently, lack of comparability of setting-specific measures has hampered progress in the field.29 To improve the quality of post-acute rehabilitation care, it is critical to develop a comprehensive outcome measurement system that can be employed across the full range of post-acute care environments through an entire episode of care. Although IRT-based instruments have provided a framework for such a system, fixed, short-form versions are needed for settings where computing is not possible. The previously published outpatient short forms for the Basic Mobility and Daily Activity scales15 and this new instrument yield a complete set of outpatient short forms for the scales of the AM-PAC which can be used as alternatives when CAT administration is not feasible.

IRT methods can be used to enable continuity of outcome measurement across rehabilitation settings and the functional continuum. There are few studies reporting on the performance of tailored short forms from IRT-based instruments. Preliminary research into the properties of the short forms for the Basic Mobility and Daily Activities scales of the AM-PAC demonstrated promising reliability and content coverage compared to the full item banks.14,15 Studies of the Patient Reported Measurement Information System (PROMIS) are beginning to compare tailored short forms to other measures. One PROMIS study on the measurement of depression found marginally better overall performance by the CAT compared to the short form, but very high correlations between the short form and the full item bank.21 In the domain of physical function, the PROMIS 10-item CAT demonstrated superior measurement characteristics compared to its short forms, and such instruments as the Health Assessment Questionnaire and SF-36.30 The 20-item short form provided better measurement than traditional fixed-form comparators with more items. The 10-item short form did well in a general population sample and less well among persons with disability.

While CATs show promise for efficient outcome measurement across settings, many post-acute care settings do not have access to point of care computing technology that is essential to the administration of these instruments using CAT. Thus, short forms connected to CATs through their calibrated item bank provide an important bridge across instruments and toward improving measurement across post-acute care settings.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, the items selected for this Applied Cognition short form were optimized for patients in outpatient rehabilitation. Therefore the Applied Cognition short form may be less appropriate for patients served in other care settings. Secondly, the subjects in this study were a convenience sample of patients drawn from rehabilitation settings in the Boston area. As with any convenience sample, there are limits to the generalizability beyond the populations served by these settings. Finally, this short form provides broad coverage of the Applied Cognition item bank using 15 items. In developing this short form, the objective was to strike a balance between the need for high quality measurement and to minimize the data collection burden for patients and clinicians. More research is needed to better understand the cognitive functioning of patients undertaking rehabilitation, and to investigate the relationships between applied cognitive functioning and specific conditions. This knowledge can be used to guide item selection by subgroup and refine and potentially streamline future short forms. The goal of this project to develop a short form covering a wide range of function and content to allow clinical measurement and future research in settings without computer access at the point of care.

In summary, these analyses demonstrated that a psychometrically adequate rehabilitation short form could be developed from the 44-item AM-PAC Applied Cognition item bank. The 15-item Applied Cognition short form yields a useful instrument that can be applied across rehabilitation settings where point of care computing is not available for use. The use of IRT methods to provide a common score scale across instruments derived from the same calibrated item bank enables providers and researchers choose the most appropriate instrument for their setting while maintaining the ability to track functional outcomes across instruments and post-acute care settings.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Comparison between Test Information Function for item selection with/without setting target information value

*: item selection without setting target information value

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Measuring Outcomes (H133B990005); R01 HD43568 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD); the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); and a New Investigator Fellowship Training Initiative (NIFTI) in Health Services Research from the Foundation for Physical Therapy. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDRR, NICHD, AHRQ, or the Foundation for Physical Therapy.

Dr. Jette has stock interest in CRE Care, LLC which distributes the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) Products.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

All other authors have no relationships to declare.

Prior Presentations:

The current research has not been previously presented.

References

- 1.Heinemann AW. State of the science on postacute rehabilitation: Setting a research agenda and developing and evidence base for practice and public policy. Assistive Technology. 2008;20(1):55–60. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2008.10131932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coster WJ, Haley SM, Ludlow LH, Andres P, Ni PS. Development of an Applied Cognition Scale to Measure Rehabilitation Outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:2030–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald JF, Smith DM, Martin DK, Freedman JA, Wolinsky FD. Replication of multidimensionality of activities of activities of daily living. Journal of Gerontology. 1999;48(S28–31) doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.1.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajek VE, Gagnon S, Ruderman JE. Cognitive and Functional assessments of stroke patients: an analysis of their relation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacNeil S, Lichtenberg P. Home alone: the role of cognition in return to independent living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:755–758. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haley SM, Coster WJ, Andres PL, et al. Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Med Care. 2004 Jan;42(1 Suppl):I49–I61. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000103520.43902.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haley SM, Siebens H, Coster WJ, et al. Computerized adaptive testing for follow-up after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. Guide for the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation (including the FIMTM instrument), Version 5.1. Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JN, Murphy K, Nonemaker S. Long-term Resident Care Assessment User's Manual. Version 2.0. Washington, DC: American Health Care Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaughnessy P, Crisler KS, RE S. Medicare's OASIS: Standardized Outcome and Assessment Information Set for Home Health Care - OASIS B. Denver CO: Center for Health Services and Policy Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella D, Chang C-H. A discussion of Item Response Theory and its applications in health status assessment. Medical Care. 2000;38(9) Supplement II:66–72. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200009002-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velozo CA, Kielhofner G, Lai JS. The use of Rasch analysis to produce scale-free measurement of functional ability. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:83–90. doi: 10.5014/ajot.53.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, Choi S. The future of outcome measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Supplement 1):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2004;85(4):649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jette AM, Haley SM, Ni P, et al. Adaptive short forms for outpatient rehabilitation outcome assessment. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2008 Oct;87(10):842–852. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318186b7ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haley SM, Ni P, R H, Slavin M, Jette AM. Computer adaptive testing improved accuracy and precision of scores over random item selection in a physical functioning item bank. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1174–1182) doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jette AM, Haley SM, Tao W, et al. Prospective evaluation of the AM-PAC-CAT in outpatient rehabilitation settings. Physical Therapy. 2007;87(385–398) doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haley S, Ni P, Jette A, et al. Replenishing a computerized adaptive test of patient-reported daily activity functioning. Quality of Life Research. 2009 May;18(4):461–471. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9463-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE., Jr Calibration of an item pool for assessing the burden of headaches: an application of item response theory to the headache impact test (HIT) Quality of Life Research. 2003 Dec;12(8):913–933. doi: 10.1023/a:1026163113446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604–607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(1):125–136. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeWitt EM, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: built using item response theory. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011 Jul;64(7):794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murnki E. Information functions of the generalized partial credit model. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1993;17:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodd B, Koch W. Effects of variations in item step values on item and test information in the partial credit model. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1987;11:371–384. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen M, Cai L, Stucky BD, Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Edelen MO. Methodology for Developing and Evaluating the PROMIS(R) Smoking Item Banks. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013 Aug 13; doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varni JW, Magnus B, Stucky BD, et al. Psychometric Properties of the PROMIS® Pediatric Scales: Precision, Stability, and Comparison of Different Scoring and Administration Options. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23:1233–1243. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raju NS, Price LR, Oshima TC, Nering ML. Standardized conditional SEM: A case for conditional reliability. . Applied Psychological Measurement. 2007;31:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson M, Holthaus D, Harvell J, Coleman E, Eilertsen T, Kramer A. A Medicare post-acute care quality measurement: final report. University of Colorado Health Sciences Center; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fries JF, Witter J, Rose M, Cella D, Khanna D, Morgan-DeWitt E. Item response theory, computerized adaptive testing, and PROMIS: assessment of physical function. Journal of Rheumatology. 2014 Jan;41(1):153–158. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying The Rasch Model Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences. New York, NY, USA: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Comparison between Test Information Function for item selection with/without setting target information value

*: item selection without setting target information value