Abstract

A subpopulation (60–70%) of Foxp3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells in both mouse and man express the transcription factor, Helios, but the role of Helios in Treg function is still unknown. In order to examine the function of Helios in Treg cells, we have generated Treg-specific Helios deficient mice. We show here that this selective deletion of Helios in Tregs leads to slow, progressive systemic immune activation, hypergammaglobulinemia, and enhanced germinal center formation in the absence of organ specific autoimmunity. Helios deficient Treg suppressor function was normal in vitro as well as in an in vivo inflammatory bowel disease model. However, Helios deficient Treg cells failed to control the expansion of pathogenic T cells derived from scurfy mice and failed to mediate T follicular regulatory cell function and control both TFH and Th1 effector cell responses. In competitive settings, Helios deficient Tregs, particularly effector Tregs, were at a disadvantage, indicating that Helios regulates effector Treg fitness. Thus, we have demonstrated, for the first time, that Helios controls certain aspects of Treg suppressive function, differentiation and survival.

Introduction

A functional immune system is dependent on the maintenance of gene expression and transcription factors play critical roles in regulating gene expression at specific stages of development. The Ikaros transcription factor family is one such family whose expression is indispensable for immune system development and function. A targeted mutation of the DNA binding domain of Ikaros (Ikzf1) acts in a dominant negative fashion to functionally delete the entire Ikaros family and results in the lack of all lymphoid lineages, while a targeted mutation of the dimerization domain of Ikaros results in the lack of B cells, NK cells, fetal T cells, with reduced numbers of thymic dendritic cells (1, 2). Mice with a similar targeted mutation of the conserved dimerization domain of Aiolos (Ikzf3) exhibit an increase in germinal centers, activated B cells, an elevation in serum IgG and IgE levels and these mice eventually develop B cell lymphomas (3). Aiolos has also been shown to inhibit IL-2 expression in Th17 cells (4). Finally, a targeted mutation of Helios (Ikzf2) is neonatal lethal (5). This finding was somewhat surprising in light of the fact that Helios expression was originally thought to be confined to a subset of T cells (6, 7) and was later shown to be restricted specifically to T regulatory (Treg) cells. However, mice with a T cell-specific deletion of Helios (crossed to CD4Cre) appeared to have normal Treg function (8 and unpublished data).

Tregs that are characterized by the transcription factor Foxp3 suppress immune activation in a dominant manner and play a critical role in the maintenance of self-tolerance. Distinct phenotypic subpopulations of murine Tregs have recently been described, broadly dividing Treg into naïve (resting or central, CD44loCD62Lhi, CCR7+) and effector (memory, CD44hiCD62Llo, CCR7−) subpopulations (9–11). Effector/memory populations of Tregs can be characterized by their ability to express T helper lineage specific transcription factors in addition to Foxp3 and can control their corresponding T effector responses. Thus, T-bet, which is required for Th1 differentiation, is also induced in Tregs during a Th1 inflammatory response and is required for Treg control of Th1 responses (12). Similarly, Treg expression of IRF4 is important for suppression of Th2 responses (13) and Treg specific deletion of STAT3 results in a failure to control Th17 responses (14). This model may be more complex than originally proposed as Treg-specific deletion of GATA3 or T-bet alone had no effect, but the deletion of both resulted in severe autoimmunity characterized by increased cytokines of all subsets (IL-4, IFNγ and IL-17) (15, 16). While the transcription factor Bcl6 controls T follicular helper (TFH) development and is expressed by Foxp3+ T follicular regulatory (TFR) cells, mice with a Treg-specific deletion of Bcl6 do not exhibit spontaneous inflammatory disease, but develop enhanced Th2-mediated airway inflammation following immunization (17–20). Bcl6 deficient Tregs express higher levels of GATA3 compared to wild-type (WT) Tregs and it appears that Bcl6 controls the Th2 inflammatory activity of Tregs by repressing GATA3 function (20, 21).

Our previous studies demonstrated that Helios was expressed by 70–80% of mouse and human Foxp3+ peripheral Tregs and suggested that expression of Helios allowed the differentiation of thymus derived (t)-Tregs from peripherally induced (p)-Tregs (8). Helios was not expressed in antigen-specific Foxp3+ T cells induced by antigen feeding or in Treg induced in germ-free mice following exposure to bacteria (22). However, this finding has been called into question (23–26) and the function of Helios and the role it may play in Tregs is still unknown. Although expression of Helios appeared to be Treg-specific, our subsequent studies demonstrated that Helios expression is induced in activated T cells following immunization in vivo (unpublished) and that Helios can be expressed by both Th2 cells and TFH cells in vivo (27). These latter studies raised the possibility that our previous failure to observe a phenotype in mice with a T cell-specific deletion of Helios (Heliosfl/fl x CD4Cre) may have been masked by deletion of Helios in both Treg and conventional CD4 T cells (Tconv). To definitively examine the function of Helios in Treg cells, we have now generated mice with a Treg specific deletion of Helios by crossing Heliosfl/fl mice to Foxp3YFP-Cre mice. These mice initially developed normally, but with increasing age exhibited splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and lymphocytic infiltrates in non-lymphoid tissues, particularly the salivary glands and liver. Most notably, Tconv cells in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3YFP-Cre mice displayed an activated, Th1-phenotype, had lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, increased numbers of germinal centers, and increased serum Ig levels secondary to the failure of TFR cell function. Helios deficient Treg suppressor function in vitro was normal as was their capacity to inhibit the induction of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in vivo. However, Helios deficient Tregs failed to control the expansion of pathogenic T cells derived from scurfy mice in an adoptive transfer model. In competitive settings, the Helios deficient Tregs also displayed a marked survival disadvantage. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that Helios plays a critical role in controlling certain aspects of Treg suppressive function, differentiation and survival.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice bearing loxP-flanked (fl/fl) alleles of Ikzk2 (Helios) on a C57BL/6 background were generated by Ozgene (Bently Dc, Australia) (8). Ikzf2fl/fl mice were bred to mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Foxp3 promoter (Foxp3-YFP Cre) (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate Treg specific Helios deficient mice. B6.SJL and B6.SJL RAG−/− mice (expressing the CD45.1 congenic marker) were obtained by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NAID) and were maintained by Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) under contract by NIAID. All animal protocols used in this study were approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies and reagents

The following staining reagents were used: APC anti-CD95 (15A7), PE anti-CD19 (eBio1D3), PE anti-PD-1 (J43), CXCR5 biotin (SPRCL5), APC eFluor 780 anti-CD4 (RM4-5), eFluor 450 anti-CD19 (eBio1D3), Alexa Fluor 700 anti-CD44 (IM7), FITC anti-Helios (22F6), PE anti-CD25 (PC61.5), PE anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), PE anti-CD62L (MEL-14), PE anti-IFN-γ (XM61.2), and eFluor 450 anti-CD4 (RM4-5) were all purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). FITC anti-GL7 (GL7), Pacific Blue anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), PE-Cy7 Streptavidin, FITC anti-CD4 (RM4-5), PE anti-CXCR3 (CD183) (CXCR3-173), and PE anti-OX40 (OX-86) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). FITC anti-CD45Rb (16A), PE anti-CD103 (M290), PE anti-Ki-67, PE anti-CD8a (53–6.7), PE anti-CD25 (7D4), PE anti-Bcl-2 and CD16/32 (24G2) were all purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Alexa Fluor 488 anti-GFP was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY).

Flow cytometry analysis

Thymus, spleen, Peyer’s patches (PP), and lymph nodes (LN) were harvested from mice at the indicated ages. Unless noted, staining was performed using the Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For cytokine staining, cells were stimulated for 4h with Cell Stimulation Cocktail (eBioscience), and stained for surface molecules followed by intracellular staining with BD Cytofix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Flow cytometry was performed on a LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Ashland, OR). Staining for YFP was done during the intracellular staining using an anti-GFP antibody (Life Technologies).

Pathology

Male and female Heliosfl/fl and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3YFP-Cre mice were sent to the NIH Division of Veterinary Resources (DVR) to be assessed. Gross necropsies and blood chemistries were performed by a DVR Pathologist.

Histology

Spleen, salivary glands, and liver from Heliosfl/fl and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3YFP-Cre mice were sent to American Histo Labs Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD) for sectioning and H & E staining. Images were taken in the Biological Imaging Section, NIAID, NIH. For histology scores, the degree of infiltrate in liver and lung was determined by two independent scorers and was scored blind.

ELISAs

The Mouse Anti-Nuclear Antibodies (ANA) Total Ig kit was purchased from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, Texas). The Mouse anti-dsDNA ELISA kit was purchased from BioVendor Research and Diagnostic Products (Asheville, NC). Mouse IgG1 ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgG2a ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgG2b ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgG3 ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgM ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgA ELISA Ready-SET-Go!, Mouse IgE ELISA Ready-SET-Go! were purchased from eBioscience.

IBD

CD4+CD45Rbhi (4 × 105) FACS sorted cells were transferred alone or with CD4+CD25+ (2 × 105) FACS sorted cells from Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3YFP-Cre mice to B6.SJL RAG−/− mice. Mice were monitored for weight loss for the indicated time.

Scurfy cell transfer

Splenocytes (2 × 106) from 21d male scurfy mice were transferred i.v. to B6 RAG−/− mice alone or with CD4+CD25+ (5 × 105) FACS sorted cells from Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3YFP-Cre mice. At 6 weeks, splenocytes were analyzed for CD4 and CD8 expression.

Mixed bone marrow chimeras

For the generation of mixed bone marrow chimeras, recipient female B6.SJL RAG1−/− mice were sublethally irradiated (550 rads) and reconstituted i.v. with a 1:1 mixture of bone marrow cells from B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice and bone marrow cells from either C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mice or Helios deficient (CD45.2) mice for a total of 2 × 106 cells. Mice were analyzed 8 weeks after reconstitution.

Immunohistochemistry

Spleens were placed in Tissue-Tek optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek), snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80° C until sectioned by HistoServ (Gaithersburg, MD). Affixed cryostats sections (6μm in thickness) were dried at 25° C, fixed in ice-cold acetone for 10 min and dried again at 25° C. Slides were rehydrated in 1x Tris-buffered saline (TBS) pH 7.6, place in a humidifier chamber. Sections were blocked for 2h at 25° C with IHC/ICC Blocking High Protein Buffer (eBioscience). Sections were stained overnight at 4° C in blocking buffer with anti-IgD (11–26c) PerCP e-Fluor 710 (eBioscience), anti-CD4 (GK1.5) Alexa Fluor 647 (Biolegend), anti-GL7 Alexa Fluor 488 (Biolegend). Slides were then washed in 1x TBS for 5 min with gentle agitation. Slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G with DAPI (eBioscience). Images were visualized and collected using a Leica SP8 inverted 5-channel confocal microscope (Leica) and analyzed in Imaris 8.1 (Bitplane, Oxford Instruments).

Immunization

For primary responses, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 2 × 108 SRBC purchased from Lampire Biological Laboratories (Pipersville, PA). Spleens were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry after 7d.

Methylation analysis of Treg specific demethylated region

The CD4+CD25− and CD4+ CD25+ cell populations were sorted using a FACS Aria cell sorter. The genomic DNA was isolated using a DNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), bisulfite conversion was performed using a EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen Valencia, CA) and the samples were then prepared for pyrosequencing using Pyromark Gold q96 reagents (Qiagen Valencia, CA) and run on the Pyromark 96ID (Qiagen Valencia, CA).

Suppression assay

CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ cells from LN and spleen were labeled with Pacific Blue anti-CD4 and PE anti-CD25 and sorted using a FACS Aria cell sorter. Alternatively, CD4+YFP− cells from Foxp3Cre mice and CD4+YFP+ Treg cells from Foxp3Cre mice or heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice were sorted using a FACS Aria cell sorter. Suppression assays were performed as previously described (8).

Statistics

All data are presented as the mean values ± SD. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t tests (Prism GraphPad). Statistical significance was established at the levels of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001.

Results

Characterization of Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice

To elucidate the role of Helios, we have generated a mouse with a Treg-specific deletion of Helios by breeding Heliosfl/fl mice that contain loxP sites flanking Exon 8 (8) to Foxp3YFP-cre mice (28). While the percentage of Foxp3+ T cells in the offspring was normal, expression of Helios could not be detected in Foxp3+ T cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). It should also be noted that the small number of Foxp3−Helios+ T cells present in C57BL/6 mice (8) and in the Heliosfl/fl mice (Fig. 1A) was unchanged in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice. It has been recently reported that some conditional alleles are subject to promiscuous expression of the Foxp3YFP-cre allele with deletion of the allele in Foxp3− CD4+ T cells (29). However, CD4+Foxp3− cells in these Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice do not express YFP, thus confirming the specificity and faithfulness of the Treg specific Helios deletion.

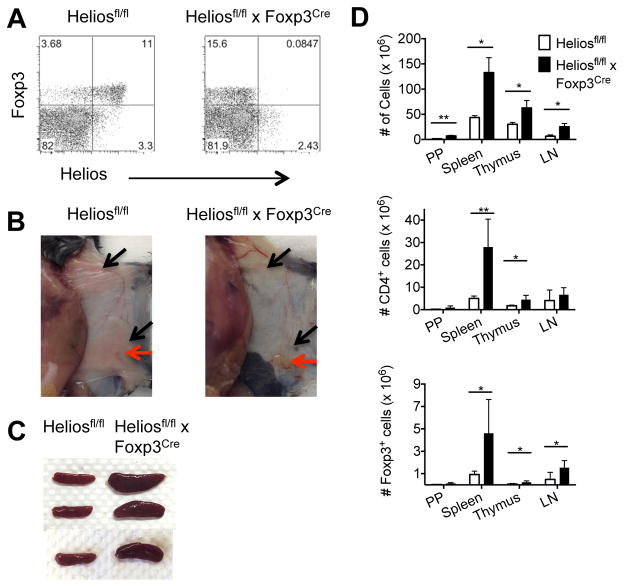

FIGURE 1. Treg specific Helios deficient mice display an altered phenotype at 6 months.

(A) Splenocytes were gated on CD4+ cells from Heliosfl/fl (left) or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre (right) mice. (B) Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (right) exhibit lymphadenopathy (red arrows) and lack adipose tissue (black arrows). (C) Spleens from 7 mo old mice. (D) Single cell suspensions from the indicated lymphoid organs were counted. For CD4+ cells and Foxp3+ cells, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and gated on CD4+ cells or CD4+Foxp3+ cells to determine percentage. Results are from three independent experiments (n=6). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.005 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

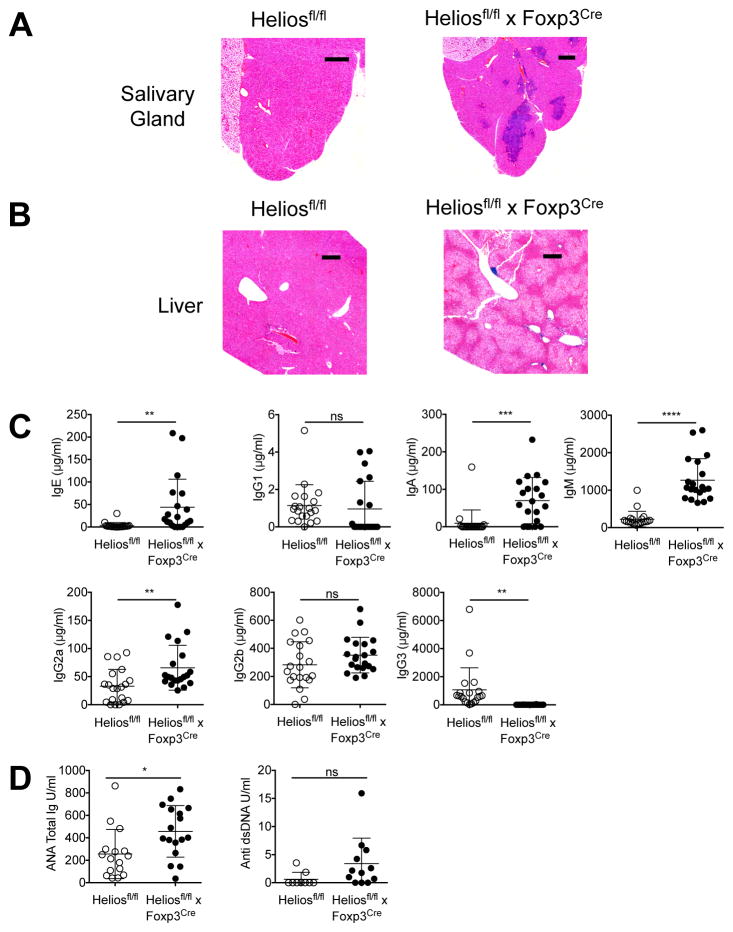

At 6 months of age, discernable abnormalities were observed in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice. A marked lymphadenopathy, specifically in the inguinal, brachial, and axillary lymph nodes, was noted (Fig. 1B) along with splenomegaly (Fig. 1C). The absolute total cell numbers were increased in all lymphoid organs, while CD4+ T cells and Treg cells were increased in most lymphoid organs (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice exhibited a greatly reduced amount of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue accompanied by significant weight loss (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. 1A, 1B). Notably, these mice also displayed signs of hepatic lipidosis and marked enlargement of the liver with increased levels of alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase present in the serum (Supplemental Fig. 1A, 1C). Perivascular lymphoid aggregates were observed in several organs including the submandibular salivary gland and liver of the Helios deficient mice (Fig. 2A, 2B). Older mice (> 9 mo) frequently presented with distended abdomens due to enlargement of the liver. Serum Ig levels were also measured and elevations in IgE, IgA, IgM and IgG2a were observed in Helios deficient mice, while a decrease was observed in IgG3 (Fig. 2C). Finally, anti-nuclear antibodies could also be detected in the sera of Helios deficient mice and although there was a trend towards higher levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies, it was not statistically significant (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2. Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice have a systemic immune activation.

(A) Salivary glands and (B) liver were sectioned and stained with H&E. Scale bars, 20 and 30 mm, respectively. (C) Sera from Heliosfl/fl and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were analyzed by ELISA for the indicated Ig isotype. (D) Sera from Heliosfl/fl and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were analyzed by ELISA for the presence of anti-nuclear Ig and anti ds-DNA IgG. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

Both Tconv cells and Treg exhibit an activated phenotype in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice

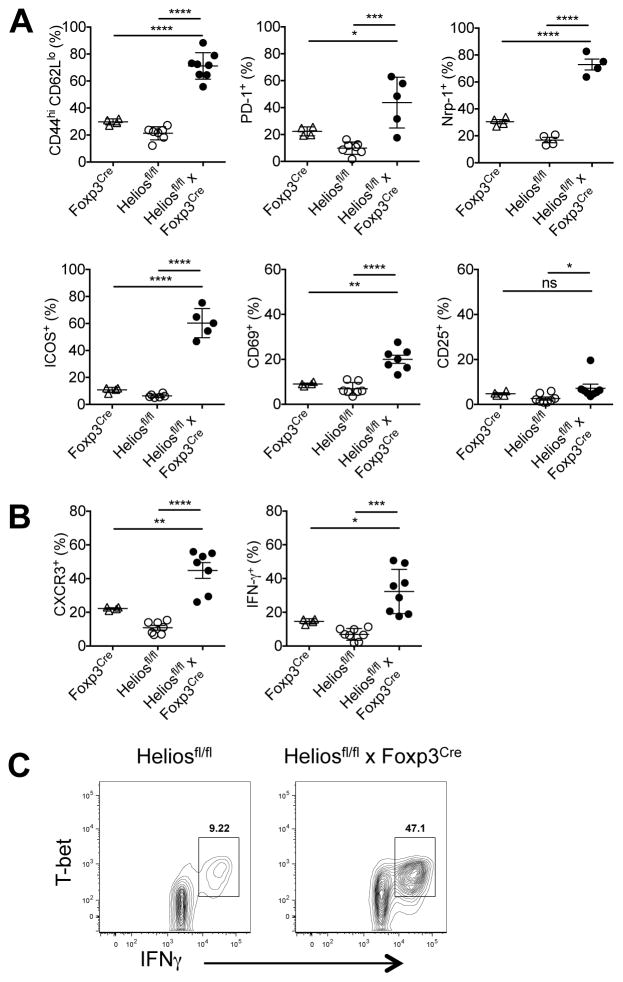

To further investigate the phenotype of the T cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, we examined a variety of activation markers. Tconv cells from two month-old Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice showed slightly elevated expression of activation markers compared to either Foxp3Cre or Heliosfl/fl mice (data not shown). However, striking differences between Tconv cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice and both Foxp3Cre and Heliosfl/fl mice were observed at 6 months. Tconv from the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice exhibited a markedly activated phenotype with significantly elevated percentages of CD44hiCD62Llo, PD-1, Nrp-1, ICOS, and CD69 cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, Tconv cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice displayed a Th1 phenotype with elevated expression of CXCR3 and an increased capacity to secrete IFN-γ compared to cells from control mice concurrent with increased expression of T-bet (Fig. 3B, 3C). Excess production of other cytokines (IL-4 and IL-17) was not observed (data not shown). In parallel, CD8+ T cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice displayed modest changes at 2 months (data not shown), but displayed a significant increase in total cell number (Supplemental Fig. 2A). CD8+ T cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice also displayed increased activation as measured by CD44hiCD62Llo expression, and a significant increase in IFN-γ production at 6 months (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 3. CD4+ cells in Helios fl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice exhibit an activated phenotype.

(A) Splenocytes were gated on CD4+Foxp3− cells and analyzed for the indicated activation markers. Splenocytes were stimulated for 4h with Cell Stimulation Cocktail, gated on CD4+Foxp3− cells and then analyzed for (B) CXCR3 and IFN-γ expression or (C) T-bet and IFN-γ expression. Results are from at least three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

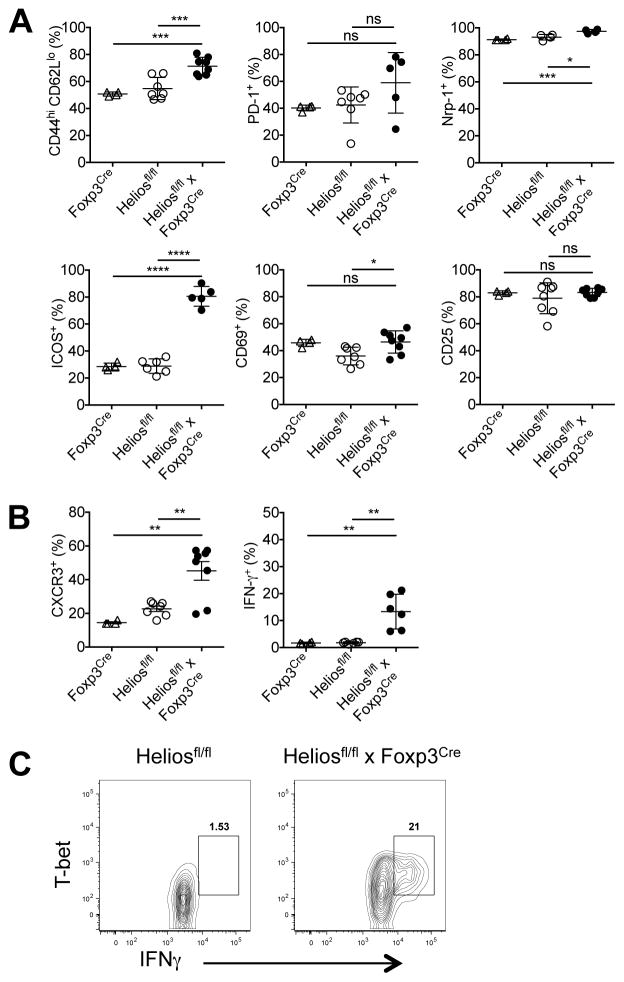

To explain this Th1 dysregulation, we examined the Tregs from 6 month-old Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice. These cells exhibited a slightly activated phenotype with higher percentages of CD44hiCD62Llo cells and elevated expression of Nrp-1, ICOS and CD69, but CD25 expression was unchanged (Fig. 4A). Tregs from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice also had elevated expression of CXCR3 and more importantly, had an increased capacity to secrete IFN-γ compared to cells from control mice (Fig. 4B) suggesting that “Th1-like” Tregs were less functional and unable to control Th1 responses. Significantly, Tregs that secreted IFN-γ also expressed T-bet (Fig. 4C). Taken together, a Treg-specific deletion of Helios results in the slow development of a complex systemic autoimmune disease with a Th1 phenotype accompanied by hepatosplenomegaly, hepatic lipidosis, and a loss of subcutaneous and visceral fat.

FIGURE 4. Tregs in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cremice are unstable.

(A) Splenocytes were gated on CD4+Foxp3+ cells and analyzed for the indicated activation markers. Splenocytes were stimulated for 4h with Cell Stimulation Cocktail, gated on CD4+Foxp3+ cells and then analyzed for (B) CXCR3 and IFN-γ expression or (C) T-bet and IFN-γ expression. Results are from at least three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

Tregs from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice are not impaired in their in vitro suppressive functions, but partially impaired in their in vivo suppressive functions

Although the absolute number of Tregs in 6 month-old Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice was elevated, it remained possible that the composition of the peripheral T cell pool was altered in the absence of Helios with a disordered ratio of thymic (tTreg) to peripheral (pTreg) Tregs. Selective demethylation of an evolutionarily conserved element within the Foxp3 locus, the TSDR, has proven to be critical for the regulation of Treg stability and pTreg may display a less stable Foxp3 expression (30). To examine Treg stability in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, we sorted CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− populations from Heliosfl/fl and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice and examined methylation of the TSDR. In both control and Helios deficient Treg populations, the TSDR was equally demethylated at both 2 and 6 months of age (Fig. 5A and data not shown). Thus, Helios does not directly control the stability of Foxp3 expression.

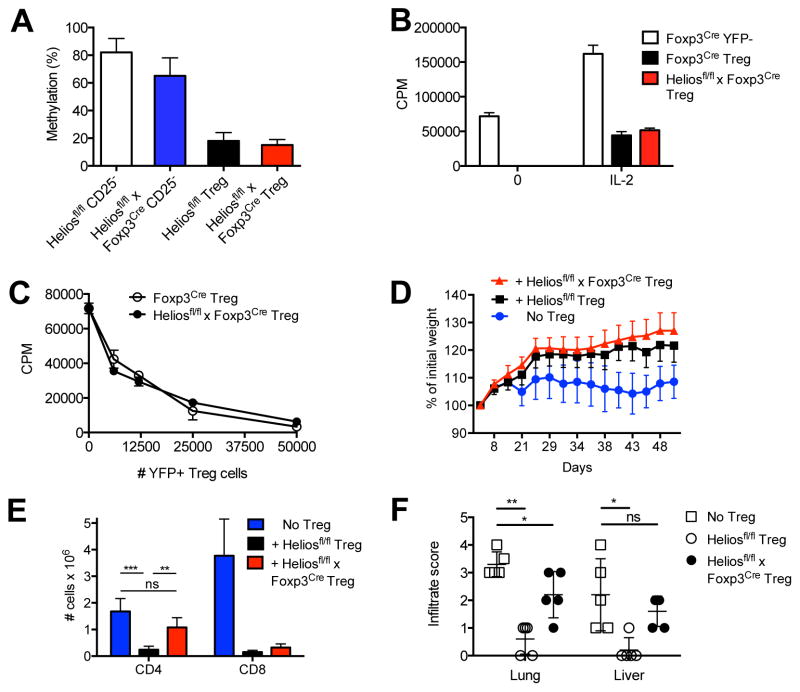

FIGURE 5. Helios deficient Tregs are functionally impaired.

(A) Sorted CD4+CD25− and CD4+ CD25+ populations from 6 mo old male mice were analyzed for methylation at the Foxp3 TSDR region. Data is from two independent experiments. (B) Sorted CD4+YFP− cells from Foxp3Cre mice or CD4+YFP+ cells from Foxp3Cre mice or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice (5 × 104) were stimulated with T depleted splenocytes (5 × 104) and anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of IL-2 for 3d. (C) Sorted CD4+YFP− cells from Foxp3Cre mice were stimulated with T depleted splenocytes and anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of sorted CD4+YFP+ Treg cells from Foxp3Cre mice or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice for 3d. (D) CD4+CD25−CD45Rbhi T cells (4 × 105 cells/mouse) from 8 week old mice were injected r.o. into 8–10 week old B6.SJL RAG−/− recipients. CD4+CD25+ cells (4 × 105 cells/mouse) from Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were co-injected where indicated. Mice were monitored weekly for weight loss. Data is plotted as percent weight change from original weight and is representative of two independent experiments (n=4 and n=5 per group, respectively). (E) Splenocytes (2 × 106 cells) from 21d scurfy mice were injected i.v. into 8 week old B6.SJL RAG−/− recipients. CD4+CD25+ cells (5 × 105 cells/mouse) from Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were co-injected where indicated. After 6 weeks, splenocytes were analyzed for CD4 and CD8 expression and total numbers calculated n=5. Data is representative of two independent experiments. **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.0005 (unpaired Student’s t-test). (F) Lung and liver from mice in (E) were stained for H & E and the degree of infiltrate was scored: 0 (no infiltrate), 1 (minimal), 2 (moderate), 3 (extensive), 4 (severe).

We next tested Treg cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice in an in vitro suppression assay. First, Helios deficient Tregs were non-responsive to stimulation with anti-CD3, but proliferated in a manner similar to control Tregs to TCR stimulation in the presence of IL-2. In the in vitro suppression assay, control and Helios deficient CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells equally suppressed the proliferative responses of CD4+CD25− responder cells from both control and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (data not shown). As the Treg cells in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice have a modestly activated phenotype and activated Tregs are more suppressive, we wished to examine Helios deficient Treg that had developed under more physiologic conditions. We crossed female Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/Cre mice to male Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3wt/wt mice to produce female heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice. As Foxp3 is X-linked and genes on the X chromosome are subject to random inactivation of one allele, female mice that are heterozygous for YFP-Cre should have 50% of Treg cells that use the Foxp3wt allele and express Helios and 50% of Treg cells that use the Foxp3Cre allele and thus, do not express Helios and are marked by YFP. Since these heterozygous female mice possess a mixture of WT Tregs and Helios deficient Tregs, they do not develop the pathology described in the Helios deficient mice. When assayed, YFP+ Tregs from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice were non-responsive to stimulation with anti-CD3, but proliferated to TCR stimulation in the presence of IL-2 in a manner similar to control Tregs (Fig. 5B). In the in vitro suppression assay, YFP+ Treg cells from Foxp3Cre and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice equally suppressed the proliferative responses of CD4+YFP− responder cells (Fig. 5C).

We also compared the suppressive capacity of control and Helios deficient Treg to inhibit T cell activation in vivo. We transferred CD4+CD45Rbhi naïve cells alone into RAG−/− recipients or co-transferred control or Helios deficient Tregs and examined their capacity to inhibit the development of IBD (Fig. 5D). Both control and Helios deficient Treg equally inhibited disease induction. To evaluate the suppressive capacity of Helios deficient Treg under more inflammatory conditions, we transferred splenocytes from a pre-moribund scurfy mouse (containing highly activated T cells) to RAG−/− mice and co-transferred Helios deficient or control Treg (Fig. 5E). At 6 weeks post transfer, control, but not Helios deficient Treg, markedly suppressed the expansion of scurfy CD4+ T cells; both control and Helios deficient Treg could suppress the expansion of scurfy CD8+ T cells. Transfer of scurfy splenocytes results in severe lymphocytic infiltration in the lung and liver (Fig. 5F). Co-transfer of control Tregs was protective in both the lung and liver, but Helios deficient Tregs were only partially protective. These results suggest that Helios regulates some, but not all, of the Treg suppressive mechanisms.

Helios deficient Treg have impaired stability

We next generated mixed bone marrow chimeras to assess the fitness of Helios deficient Tregs in a competitive environment. After 8 weeks of reconstitution, the thymus and spleen were harvested. In WT/WT mice, reconstitution in the thymus and spleen were roughly equal, as expected (data not shown). In the thymus of the WT/Helios deficient mice, reconstitution of both CD4+Foxp3− and CD4+Foxp3+ cells were roughly equal demonstrating that thymic development of the Helios deficient Tregs is not impaired by the absence of Helios (Fig. 6A). However, in the spleen there was a striking decrease in the ratio of WT to Helios deficient Treg, suggesting that although the Helios deficient Treg cells were generated in the thymus, once in the periphery, their survival was greatly impaired compared to control Tregs (Fig. 6A, 6B).

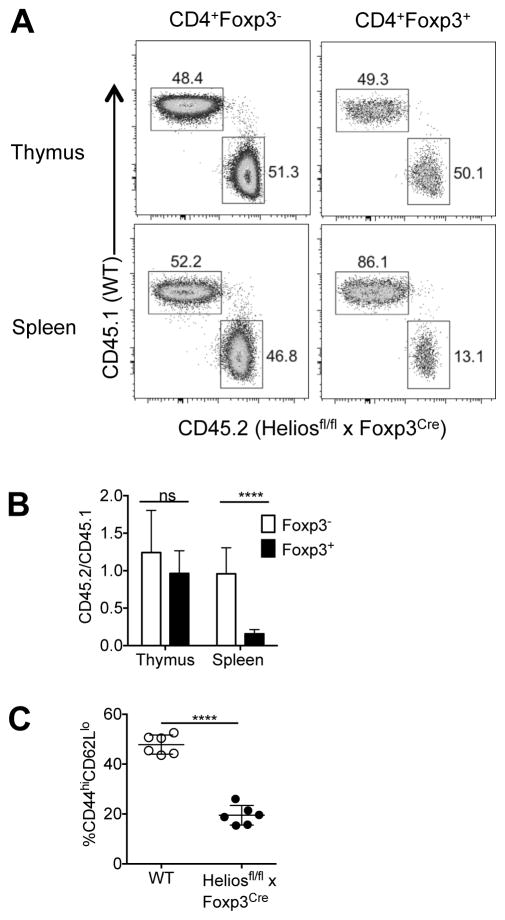

FIGURE 6. Impaired homeostasis of Helios deficient Treg cells.

Irradiated RAG−/− mice received a mixture of WT (CD45.1) and WT (CD45.2) or WT (CD45.1) and Treg specific Helios deficient (CD45.2) bone marrow cells (1 × 106 each) i.v. and were allowed to reconstitute for 8 weeks. (A) CD4+Foxp3− and CD4+Foxp3+ cells from the indicated lymphoid organs were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression and a representative dot plot is shown. (B) The average ratio of Helios deficient (CD45.2) to WT (CD45.1) cells from all mice from two independent experiments (n=10). (C) Splenic CD4+Foxp3+ cells from mixed chimera mice were analyzed for CD44 and CD62L expression. ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

As studies have demonstrated that Tregs can be divided into two distinct subpopulations based on their differential expression of CD44 and CD62L (9–11, 31, 32) we examined CD44 and CD62L expression in the mixed chimeric mice and found that the Helios deficient Tregs were deficient in cells of the activated/effector phenotype and were preferentially of the naïve/central phenotype (CD62LhiCD44lo) (Fig. 6C). The phenotype of the Helios deficient Treg in this chimeric environment must be contrasted with their phenotype in the parental Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mouse in which the majority of the Treg exhibit an activated effector phenotype. These data suggests that in a competitive setting, Helios deficient Tregs fail to differentiate to effector Treg or, alternatively, die during the transition from naive to an activated state or are unstable in the activated state.

To further examine the phenotype of Helios deficient Treg under more physiologic conditions, we further analyzed the heterozygous female Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice, as they do not develop the pathology described in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice and, unlike the bone marrow chimeric model that involves radiation of the RAG2−/− recipient, Tregs develop in a normal environment. Using YFP expression as a marker of Helios deficient Tregs, we confirmed that the thymus contains a similar ratio of YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs and YFP− WT Tregs and thus, the thymic development of YFP+ Helios deficient Treg cells does not appear to be impaired (Fig. 7A). However, in secondary lymphoid tissue, there is a reduction of YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs to approximately 35% of total Tregs as early as 2 months of age (data not shown). These differences were more pronounced at 5 months with the YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs further reduced to only 23% of the total Treg population (Fig. 7A, 7B). A comparison of the phenotype of YFP+ Helios deficient and YFP− WT Tregs revealed that YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs preferentially expressed a more naïve phenotype with reduced levels of activation markers (CD44/CD62L, OX40, CD69) (Fig. 7C), in agreement with the bone marrow chimeric data. Furthermore, CD25 expression on the YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs in the heterozygous mice was increased and the proliferation rate, as measured by the cell cycle marker Ki67, was decreased, again consistent with a naïve Treg phenotype (Fig. 7C). Finally, we examined the expression of IFNγ and T-bet. In the absence of an inflammatory environment in the female heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice, the YFP+ Helios deficient Tregs had percentages of T-bet+ IFNγ+ cells comparable to the YFP− Tregs within the same mouse (Supplemental Fig. 3). Thus, the instability of the Helios deficient Tregs is a consequence of the activated environment. Together, these data suggest that, in a competitive setting, Helios deficient Tregs are unable to differentiate or survive, particularly in an activated, effector state.

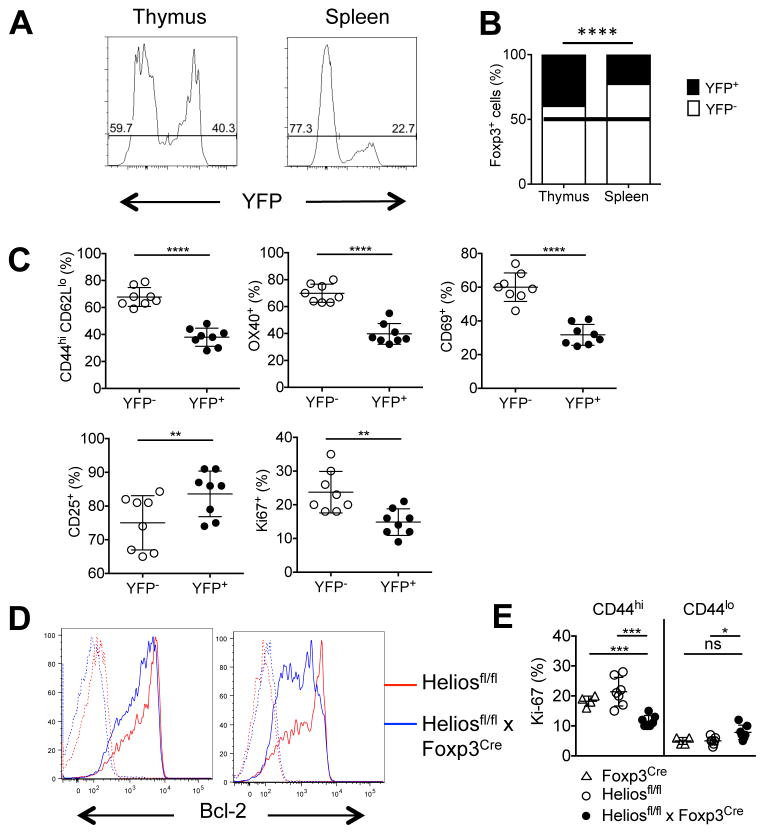

FIGURE 7. Impaired homeostasis of Helios deficient Treg cells.

(A) CD4+Foxp3+ thymocytes or splenocytes from 5 mo old mice were analyzed for YFP expression. A representative histogram is shown. (B) The average percentage of YFP− (Heliosfl/fl) or YFP+ (Helios deficient) CD4+Foxp3+ cells in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice from two independent experiments (n=8) (C) CD4+Foxp3+ splenocytes from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice were analyzed for the expression of the indicated markers. (D) Splenocytes from Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were taken ex vivo (left) or stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and IL-2 for 4h (right) and CD4+Foxp3+ cells were analyzed for Bcl-2 expression (solid line) or an isotype control (dotted line). Representative histograms from four independent experiments are shown (n=7). (E) CD4+Foxp3+ splenocytes from Foxp3Cre, Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were gated based on CD44 expression and analyzed for Ki-67 expression. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

We did not find any significant difference in the levels of expression of a broad array of either pro- or anti- apoptotic genes between thymic or peripheral YFP+ and YFP− Treg in the heterozygous female mice (data not shown). However, unstimulated Treg cells from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice expressed lower levels of Bcl-2 when compared to Heliosfl/fl mice (Fig. 7D), but no differences were seen in mRNA expression of Bim, Bcl-XL, Bad, Bid, Bax or Mcl-1 (data not shown). Upon activation, Bcl-2 expression was further decreased in Tregs from Helios deficient mice (Fig. 7D). The decreased expression of Bcl-2 in the Helios deficient Treg was paradoxical as the total Treg population is enhanced in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 1D). When we correlated Ki-67 staining with CD44 expression in control and Helios deficient Treg, we noted that CD44hi Helios deficient Treg had decreased Ki-67 compared to control CD44hi Treg, while the CD44loHelios deficient Treg had a higher level of Ki-67 than the Heliosfl/fl CD44lo Treg (Fig. 7E). Thus, it appears that in both competitive and non-competitive conditions, Helios deficient CD44hi Treg are at a competitive disadvantage. In the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, this deficiency is compensated by enhanced expansion of the CD44lo population.

TFR cells are non-functional in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice

Given the increased spleen size and the pan-hypergammaglobulinemia in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 1C, 2C), we stained spleen sections to examine for the presence of germinal centers. Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice possess an increased number of follicles, and strikingly increased germinal centers (Fig. 8A). This suggests that Helios might play a role in the differentiation of TFR cells, specialized Tregs that control TFH cells and germinal center responses (17–19). We first compared the presence of TFH cells and TFR cells in unimmunized control and Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 8B). Unimmunized control mice have few follicular T cells based on CXCR5+ and PD-1hi expression, but ~45% of those present are Foxp3+ TFR cells. In marked contrast, unimmunized Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice have an enhanced percentage of PD-1+CXCR5+ follicular T cells, but very few are Foxp3+ TFR cells. In addition, Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice also have a higher percentage of germinal center B cells (Fig. 8C). Upon immunization with SRBCs, we observed an increase in T follicular cells in control mice, but no change in the already high percentage of T follicular cells and germinal center B cells in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 8D, 8E). As the percentage of TFR cells was drastically reduced in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, this suggests that in the absence of Helios, Treg cells are unable to differentiate into TFR cells. However, due to the increased cellularity of the spleen and the increased percentage of T follicular cells, calculation of the absolute number of TFR shows that, in fact, TFR are present and are increased in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 8F). Calculation of the absolute number of TFH shows a 75-fold increase in TFH in Helios/− mice.

FIGURE 8. Helios deficient TFR fail to control follicular T cells responses.

(A) Frozen spleen sections from 7 mo old mice were frozen, sectioned and stained for IgD (blue) CD4 (green), and GL7 (red). Scale bars, 1mm (Heliosfl/fl) and 1.5 mm (Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre). Quantification of active germinal centers is shown to the right. A WT mouse immunized for 7d with 2 × 108 SRBC was used as a control. (B) Splenocytes from 5 mo old Heliosfl/fl or Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice were gated on CD4+CD19− T cells and analyzed for CXCR5 and PD-1 expression (top). CXCR5+PD-1+ cells (T follicular cells) were then analyzed for Foxp3 expression to determine TFH and TFR percentages (bottom). (C) Splenocytes in (B) were gated on B220+ CD19+ cells and analyzed for CD95 and GL7 expression. (D)(E) As in (B and C) immunized with 2 × 108 SRBC i.p. and analyzed 7d post-immunization. Representative plots are shown (n ≥ 6 in at least 3 independent experiments). (F) The absolute number of TFH and TFR from unimmunized mice (n= 8 from 3 independent experiments). Splenocytes from 2 mo old Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice, either (G) unimmunized or (H) immunized as above were analyzed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD19− splenocytes were gated on T follicular cells (CXCR5+ ICOS+) then gated on TFR cells based on Foxp3 expression and then analyzed for YFP expression. Representative plots are shown in the left three panels and the average YFP expression is shown in the right panel. **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, and ****p < 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

We further examined Treg cells for the presence of TFR cells in the heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ female mice. Gating on CD4+ Foxp3+ cells from 2 month-old heterozygous mice, the YFP+ Helios deficient TFR population in the heterozygous mice was totally absent (Fig. 8G). Similar results were observed in the 5 month-old heterozygous mice (data not shown). Upon immunization with SRBCs, we observed an increase in T follicular cells in the heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ female mice, but no TFR were derived from the YFP+ Helios deficient population (Fig. 8H).

Discussion

We have found that selective deletion of Helios in Foxp3+ Treg results in the development of a systemic autoimmune disease in mice beginning at 2 months of age. At 6 months of age, Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice exhibit generalized splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, lymphocyte activation, expansion of Th1 Teff cells, hypergammaglobulinemia, and increased size/numbers of lymphoid follicles and germinal centers. Our results suggest that Helios plays a critical role in controlling Treg-mediated regulation of Th1 and TFH effector functions. In addition, the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice have a marked abnormality of lipid metabolism characterized by a complete absence of subcutaneous and visceral fat and markedly enlarged livers with lipidosis. None of these abnormalities were observed in aged mice with a deletion of Helios in mature T cells (CD4-Cre) or in T cell precursors (Vav-Cre). It is therefore likely that Helios plays an important functional role in Tconv cells and that loss of Helios expression in Tconv masks the effect of loss of Helios in Treg. Studies are currently underway to elucidate the potential role that Helios may play in CD4+Foxp3− cells.

The phenotype of the Tregs in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice differed from the Treg phenotype observed in both the mixed bone marrow chimeras and the heterozygous Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice. The former expressed an activated phenotype, while the Helios deficient Tregs in the competitive environments had a predominantly naïve phenotype. It is likely that in the non-competitive setting, the Helios deficient Tregs are continuously activated and are abortively attempting to control the Th1 Teff and TFH responses. In the competitive settings, mice are phenotypically normal, and Helios sufficient Tregs effectively control Teff cell function. It is therefore unlikely that Helios controls the differentiation of naïve Treg to Teff/memory Treg, as the Treg in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice express an activated phenotype, while the failure to observe activated Helios deficient Treg in the competitive environments is consistent with a role of Helios in controlling Treg fitness. Although the absolute numbers of Treg in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice was elevated, these Treg expressed reduced levels of Bcl-2 and decreased percentages of Ki-67+ CD44hi cells. This result is also consistent with the decrease in survival of activated/effector Helios deficient Treg in the heterozygous females and bone marrow chimera animals. Although Bcl-2 deficient Treg cells do not appear to have any defects in survival in mixed bone marrow chimeras generated from mice with a global deletion of Bcl-2 (33), survival of Treg in mice with a Treg specific Bcl-2 deficient mouse has not been reported and the role of Bcl-2 in Helios deficient Treg cells will need to be further examined. It is likely that the enhanced numbers of Treg in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice are secondary to enhanced proliferation of the Helios deficient CD44lo population or increased thymic output.

One other problem in interpreting our results, particularly in the competitive environment models, is that Foxp3-Cre is expressed in all Foxp3+ cells including the 30% of peripheral Tregs that do not express Helios. We have postulated that Foxp3+Helios− Tregs are pTreg, but several studies (34) have raised questions about this finding. Nevertheless, it is quite likely that a majority (~60%) of Foxp3+Helios− Tregs are pTreg. The Tregs in the Helios deficient mouse may still be a heterogeneous population that consists of the typical 30% Helios− cells and 70% Helios “positive” cells that no longer express Helios. Alternatively, Treg cells that normally express Helios may not survive in a competitive environment once Helios has been deleted and the remaining Treg population may consist exclusively of Helios− cells. At this time, it is difficult to rule out either possibility.

Helios appears to regulate two distinct suppressor-effector functions of the Foxp3+ T cell population. Helios deficient Treg were as efficient as control Treg in suppressing the activation of naïve CD4+ T cells in vitro and also were as competent as control Treg in preventing the induction of IBD induced by transfer of CD45Rbhi cells to immunodeficient recipients. Although Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice have an expanded pool of Treg that express CXCR3, IFNγ and Tbet, Th1 responses were not controlled. Surprisingly, the marked increase in IFNγ-producing Teff cells (both CD4+ and CD8+) was not accompanied by pathologic evidence of organ-specific autoimmunity. The failure to control Th1 Teff function was also clearly documented when we transferred Teff cells (primarily Th1 cells) from moribund scurfy mice to immunodeficient mice. Control, but not Helios deficient Treg were able to control expansion of the CD4+ Teff cells. The Helios deficient Treg did control the expansion of CD8+ scurfy Teff cells suggesting that Treg may use different mechanisms to suppress CD4+ and CD8+ Teff.

Helios deficient Tregs were also incapable of controlling TFH function, as the most prominent feature of the phenotype of the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice was a marked increase in the size and number of lymphoid follicles, germinal centers, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Abnormal lymphoid follicle formation was also observed in the salivary glands. While the ratio of TFR to TFH was markedly reduced in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, the absolute number of TFR in the spleen was normal or increased secondary to the splenomegaly. Furthermore, the levels of Bcl-6 in the Helios deficient Treg are comparable to those of control Treg (data not shown). Thus, it appears that TFR cells, that express Bcl-6, can be generated in the absence of Helios, but their suppressor functions are compromised. As TFR cells are thought to arise from tTregs, not pTregs (17, 19), this result is consistent with the preferential expression of Helios in tTreg. It also suggests that the normal 30% of Treg that are CD4+Foxp3+Helios− are unable to differentiate to fully functional TFR. The defect in TFR function in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice resembles, in part, the defect in TFR function seen in mice with a Treg-specific deletion of TRAF3 (35). TRAF3−/− mice exhibited milder signs of generalized dysregulated Treg dysfunction (e.g., elevated Th1 cells in peripheral tissues). The changes in T follicular cell responses (elevated TFH and decreased TFR) were primarily seen after immunization. The defect in TFR function in these mice appeared to be related to a decreased expression of ICOS. In marked contrast to the TRAF3−/− Treg, Helios deficient Treg isolated from the spleens of 6 month old mice expressed very high levels of ICOS (Fig. 4A). Further studies of the TFR population in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice should be helpful in determining what specific suppressor mechanisms are used by TFR cells.

Obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are associated with inflammation in adipose tissue that is accompanied by proinflammatory M1 macrophages and TNFα (36). Serum levels of TNFα were not elevated in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice with NAFLD (unpublished data). More recently, another subpopulation of effector Tregs in adipose tissue has been described (37, 38). Adipose tissue-specific Tregs are characterized by expression of the transcription factor PPARγ and control adipose tissue inflammation via IL-10. At present, it is difficult to link the development of the severe NAFLD seen in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice to the Treg that are normally resident in fat, as the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice completely lack adipose tissue and are not obese. NAFLD in the Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice is only seen in mice 6 months of age and older and its severity is of variable penetrance. It remains possible that this phenotype is not a direct effect of loss of Helios in Tregs, but an indirect phenomenon perhaps secondary to the development of autoantibodies to a receptor involved in lipid metabolism. Further studies of the potential role that Helios may play in adipose tissue-specific Tregs are currently under investigation. It will also be of interest to determine if the NAFLD phenotype can be transferred by T cells or by antibody.

Taken together, our studies indicate that Helios plays a complex role in Treg function and probably also in the function of Tconv cells. The major effect of loss of Helios expression in Treg appears to be disruption of TFR function with the slow development of a systemic autoimmune disease in the absence of immunization or pathogen challenge. It also remains possible that the activated Th1 phenotype is secondary to the failure of the Helios deficient Treg to control TFH function and that the activated Th1 phenotype is secondary to abnormal differentiation of the uncontrolled TFH population. It has been claimed that Helios promotes binding of Foxp3 to the IL-2 promoter and thereby controls IL-2 expression by Tregs (39). shRNA-mediated down-regulation of Helios resulted in IL-2 production by Tregs and loss of Treg suppressive capacity in vitro and in vivo in the IBD model. It is difficult to reconcile our findings that specific deletion of Helios in Tregs had no effect on Treg suppressive function in vitro or in vivo in the IBD model. It remains possible that the differences in the studies are secondary to redundant mechanisms mediated by other members of the Ikaros gene family, but it is also possible that the shRNA approach induced expression of dominant negative proteins that interfered with other members of the Ikaros family. Ikaros itself binds to the IL-2 promoter and represses IL-2 gene expression. Although Baine et al. (39) claimed that Helios bound to the IL-2 promoter using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, it is difficult to interpret their results as the polyclonal anti-Helios antibody used in their studies was reactive with the C-terminal domain of Helios which is conserved among Ikaros family members. Ikaros, but not Helios, was identified as one of the 361 proteins associated with Foxp3 in mass-spectrometric analyses of Foxp3 complexes (40). Helios was also not identified as one of the critical transcription factors involved in the regulation of the Treg gene signature (41). Thus, Helios appears to play a niche role in the spectrum of Treg suppressive functions (42, 43) and further analysis of its specific target will require a focus on the TFR suppressive functions.

During the review of this paper, Kim et al. reported that Helios plays a critical role in Treg function and is required for the stable inhibitory activity of Treg cells due to decreased activation of the STAT5 pathway (44). Most of their experiments use mice that have a global deficiency in Helios and it is difficult to compare their results to our studies in mice with a conditional deletion of Helios in Treg. Kim et al. observed autoimmunity in aged Helios−/− mice and in bone marrow chimeras in which either CD4 or CD8 cells were deficient for Helios. However, we have never observed any signs of Treg dysfunction, T cell activation, or autoimmune disease in aged Heliosfl/fl x CD4Cre or Heliosfl/fl x VavCre mice. Similar to our results, Kim et al. (44) did observe significant T cell activation in 6-month old Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice, but they also report manifestations of autoimmune pathology in liver, lung and pancreas that we did not observe. While lymphoid infiltrates were present in the salivary glands and liver in our mice, we did not detect any signs of autoimmune-mediated organ pathology. They also reported a defect in the ability of Treg from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice to protect in the IBD model that we did not find, but this may be secondary to differences in the microbiome in the colonies.

One of the most interesting findings reported by Kim et al. was that STAT5b was a target for Helios binding and that reduced STAT5 activation was responsible for reduced expression of Foxp3 in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice. They conclude that this is consistent with the contribution of STAT5 for Foxp3 stability. We have also noted reduced Foxp3 expression in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice and in the Helios deficient cells in female Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre/+ mice. However, we did not observe any differences in STAT5 activation (not shown). It remains possible that the reduction in Foxp3 expression that they observe represents a hypomorphic feature of the Foxp3YFP-Cre allele as previously reported (29).

Lastly, one of the major differences between the two studies is that severe autoimmune disease was primarily observed when Kim et al. generated bone marrow chimeras from mice with either global or Treg-specific deletions of Helios. We have also observed severe autoimmune disease in bone marrow chimeras generated from Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice (not shown). It is likely that the thymic generation of Treg in bone marrow chimeras (generated in irradiated RAG−/− adult mice) differs markedly from the normal neonatal selection of Treg (45). Helios is expressed very early in the thymic development of Foxp3+ Treg and a deficiency of Helios may contribute to the alterations in Treg function observed in bone marrow chimeras.

Abnormalities of Treg function have been noted in almost all human autoimmune diseases based largely on decreased suppressor function in the standard Treg suppression assay in vitro (46). However, deletion of the expression of several transcription factors (including Helios) that are critical for Treg function in the mouse, while precipitating autoimmune disease, may not result in abnormalities in Treg suppressor function in vitro (35). As the major manifestation in Heliosfl/fl x Foxp3Cre mice is defective TFR function, resulting in a disease resembling systemic lupus erythematosus, it would highly desirable to develop in vitro assays of TFR function for humans that might be useful both diagnostically and to monitor therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID.

We thank Deborah D. Glass for technical help, Hideyuki Ujiie for assistance with the scurfy transfer model and Sundar Ganesan for assistance with immunohistochemistry and imaging.

References

- 1.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, Molnar A, Wu P, Winandy S, Sharpe A. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JH, Nichogiannopoulou A, Wu L, Sun L, Sharpe AH, Bigby M, Georgopoulos K. elective defects in the development of the fetal and adult lymphoid system in mice with an Ikaros null mutation. Immunity. 1996;5:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JH, Avitahl N, Cariappa A, Friedrich C, Ikeda T, Renold A, Andrikopoulos K, Liang L, Pillai S, Morgan BA, Georgopoulos K. Aiolos regulates B cell activation and maturation to effector state. Immunity. 1998;9:543–553. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintana FJ, Jin H, Burns EJ, Nadeau M, Yeste A, Kumar D, Rangachari M, Zhu C, Ziao S, Seavitt J, Georgopoulos K, Kuchroo VK. Aiolos promotess TH17 differentiation by directly silencing IL2 expression. Nat Immunol. 2014;13:770–777. doi: 10.1038/ni.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai Q, Dierich A, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Chan S, Kastner P. Helios deficiency has minimal impact on T cell development and function. J Immunol. 2009;183:2303–2311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley CM, Ikeda T, Koipally J, Avitahl N, Wu L, Georgopoulos K, Morgan BA. Helios, a novel dimerization partner of Ikaros expressed in the earliest hematopoietic progenitors. Curr Biol. 1998;8:508–515. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahm K, Cobb BS, McCarty AS, Brown KE, Klug CA, Lee R, Akashi K, Weissman IL, Fisher AG, Smale ST. Helios, a T cell-restricted Ikaros family member that quantitatively associates with Ikaros at centromeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 1998;12:782–796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huehn J, Siegmund K, Lehmann JCU, Siewert C, Haubold U, Feurer M, Debes GF, Lauber J, Frey O, Przybylski GK, Niesner U, de la Rosa M, Schmidt CA, Bräuer R, Buer J, Scheffold A, Hamann A. Developmental stage, phenotype, and mifration distinguish naïve-and effector/memory-like CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:303–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Kang SG, Kim CH. Foxp3+ T cells undergo conventional first switch to lymphoid tissure homing receptors in thymus but accelerated second switch to nonlymphoid tissue homing receptors in secondary lymphoid tissues. J Immunol. 2007;178:310–311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smiegel KS, Richards E, Srivastava S, Thomas KR, Dudda JC, Klonowski KD, Campbell DJ. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch MA, Tucker-Heard G, Perdue NR, Killebrew JR, Urdahl KB, Campbell DJ. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, Chaudhry A, Kas A, deRoos P, Kim JM, Chu TT, Corcoran L, Treuting P, Klein U, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program coopts transcription factor IRF4 to control Th2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhry A, Rudra D, Treuting P, Samstein RM, Liang Y, Kas A, Rudensky AY. D4+ regulatory T cells control Th17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science. 2009;326:986–991. doi: 10.1126/science.1172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wohlfert EA, Grainger JR, Bouladoux N, Konkel JE, Oldenhove G, Ribeiro CH, Hall JA, Yagi R, Naik S, Bhairavabhotla R, Paul WE, Bosselut R, Wei G, Zhao K, Oukka M, Zhu J, Belkaid Y. GATA3 controls Foxp3+ regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4503–4515. doi: 10.1172/JCI57456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu F, Sharma S, Edwards J, Feigenbaum L, Zhu J. Dynamic expression of transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 by regulatory T cells maintains immunotolerance. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, Nurieva RI, Martinez GJ, Rawal S, Wang YH, Lim H, Reynolds JM, Zhou XH, Fan HM, Liu ZM, Neelapu SS, Dong C. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 supress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, Srivastava M, Divekar DP, Beaton L, Hogan JJ, Fagarason S, Liston A, Smith KGC, Vinuesa CG. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat Med. 2011;17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wollenberg I, Agua-Doce A, Hernandez A, Almeida C, Oliveira VG, Faro J, Graca L. Regulation of the germinal center reaction by Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4553–4560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawant DV, Wu H, Yao W, Sehra S, Kaplan MH, Dent AL. The transcriptional repressor Bcl6 controls the stability of regulatory T cells by intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Immunol. 2015;145:11–23. doi: 10.1111/imm.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawant DV, Sehra S, Nguyen ET, Jadhav R, Englert K, Shinnakasu R, Hangoc G, Broxmeyer HE, Nakayama T, Perumal NB, Kaplan MH, Dent AL. Bcl6 controls the Th2 inflammatory activity of regulatory T cell by repressing Gata3 function. J Immunol. 2012;189:4759–4769. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Kuwahara A, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Tanaguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov II, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verhagen J, Wraith DC. Comment on “Expression of Helios an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells”. J Immunol. 2010;185:7129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akimova T, Beier UH, Wang L, Levine MH, Hancock WW. Helios expression is a maker of T cell activation and proliferation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottschalk RA, Corse E, Allison JP. Expression of Helios in peripherally induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:976–980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissler KA, Garcia V, Kropf E, Aitken M, Bedoya F, Wolf AI, Erikson J, Caton AJ. Distinct modes of antigen presentation promote the formation, differentiation, and activity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2015;194:3784–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serre K, Benezech C, Desanti G, Bobat S, Toellner K, Bird R, Chan S, Kastner P, Cunningham AF, MacLennan ICM, Mohr E. Helios is associated with CD4 T cells differentiating to T helper 2 and follicular helper T cells in vivo independently of Foxp3 expression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, Treuting P, Siewe L, Roers A, Henderson WR, Jr, Muller W, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franckaert D, Dooley J, Roos E, Floess S, Huehn J, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Liston A, Linterman M, Schlenner SM. Promiscuous Foxp3-cre activity reveals a differential requirement for CD28 in Foxp3+ and Foxp3− T cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93:417–423. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, Klein-Hessling S, Serfling E, Hamann A, Huehn J. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liston A, Gray DH. Homeostatic control of regulatory T cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:154–165. doi: 10.1038/nri3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smiegel KS, Srivastava S, Stolley JM, Campbell DJ. Regulatory T- cell homeostasis: steady-state maintenance and modulation during indlammation. Immunol Rev. 2014b;259:40–59. doi: 10.1111/imr.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierson W, Cauwe B, Policheni A, Schlenner SM, Franckaert D, Berges J, Humblet-Baron S, Schönefeldt S, Herold MJ, Hildeman D, Strasser A, Bouillet P, Lu L-F, Matthys P, Frietas AA, Luther RJ, Weaver CT, Dooley J, Gray DHD, Liston A. Antiapoptotic Mcl-1 is critical for the survival and niche-filling capacity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petzold C, Steinbronn N, Gereke M, Strasser RH, Sparwasser T, Bruder D, Geffers R, Schallenberg S, Kretschmer K. Fluorochrome-based definition of naturally occurring Foxp3+ regulatory T cells of intra-and extrathymic origin. Eur J Immunol. 2015;44:3632–3645. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JH, Hu H, Jin J, Puebla-Osorio N, Xiao Y, Gilbert BE, Brink R, Ulrich SE, Sun SC. TRAF3 regulates the effector function of regulatory T cells and humoral immune responses. J Exp Med. 2014;13:137–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNelis JC, Olefsky JM. Macrophages, Immunity, and Metabolic Disease. Immunity. 2014;41:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipoletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, Lee J, Goldfine AB, Benoist C, Shoelson S, Mathis D. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cipolletta D, Feurer M, Kamei N, Lee J, Shoelson SE, Benoist C, Mathis D. PPAR-γ is a major driver of the accumulation and phenotype of adipose tissue Treg cells. Nature. 2012;486:549–553. doi: 10.1038/nature11132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baine I, Basu S, Sellers RS, Macian F. Helios induces epigenitic silencing of IL2 gene expression in regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:1008–1016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudra D, deRoos P, Chaudhry A, Niec RE, Arvey A, Samstein RM, Leslie C, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, Rudensky AY. Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1010–1019. doi: 10.1038/ni.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu W, Ergun A, Lu T, Hill JA, Haxhinasto S, Fassett MS, Gazit R, Adoro S, Glimcher L, Chan S, Kastner P, Rossi D, Collins JJ, Mathis D, Benoist C. A multiply redundant genetic switch “locks in” the transcriptional signature of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:972–980. doi: 10.1038/ni.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevach EM, Thornton AM. tTregs, pTregs, and iTregs: similarities and differences. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:88–102. doi: 10.1111/imr.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim HJ, Barnitz RA, Kreslavsky T, Brown FD, Moffett H, Lemieux ME, Kaygusuz Y, Meissner T, Holderried TAW, Chan S, Kastner P, Haining WN, Cantor H. Stable inhibitory activity of regulatory T cells requires the transcription factor Helios. Science. 2015;350:334–339. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang S, Fujikado N, Kolodin D, Benoist C, Mathis D. Regulatory T cells generated early in life play a distinct role in maintaining self-tolerance. Science. 2015;348:589–594. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Long SA, Buckner JH. CD4+FOXP3+ T Regulatory cells in human autoimmunity: more than a numbers game. J Immunol. 2011;187:2016–2068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.