Abstract

Geotrichum species have been rarely reported as the cause of sepsis, disseminated infection in immunosuppressed patients. The patient we describe developed indolent endophthalmitis four months after her routine right eye cataract surgery. The intraoperative sample from right vitreous fluid grew Geotrichum candidum. The patient underwent vitrectomy, artificial lens explantation and intravitreal injection of amphotericin B followed by oral voriconazole. Despite these interventions, she underwent enucleation. This is the first published case of Geotrichum candidum endophthalmitis.

Keywords: Geotrichum candidum, Endophthalmitis

1. Introduction

Geotrichum species are infrequently found as part of the normal flora in humans. It has been isolated as flora from a variety of sources including respiratory specimens, mouth, intestine, vagina, and skin [1].

Geotrichum species are usually non-pathogenic, but have been rarely reported to cause actual disease. Cases of sepsis, disseminated disease, and oral and cutaneous infections in immunocompromised hosts with hematologic malignancies or human immunodeficiency virus infections have been described [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], There is one case report of traumatic joint infection in an immunocompetent patient [9].

This report describes a case of postoperative fungal endopthalmitis caused by Geotrichum candidum in a diabetic patient and discusses the potential antimicrobial therapies used to treat this organism.

2. Case

The patient was a 59-year-old female with hypertension, coronary artery disease status post coronary bypass graft surgery, hypothyroidism, diabetes complicated by proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and gastropathy. She underwent routine right eye cataract surgery followed by left eye cataract surgery a month later.

She initially had improvement in the vision of her right eye until about 3 months later when she started to have retro-orbital pain and blurred vision which was treated with topical eye drops (day 0 being the day of first symptom). She went back to her ophthalmologist approximately 45 days after development of her initial symptoms when the eye drops failed to correct her visual difficulties.

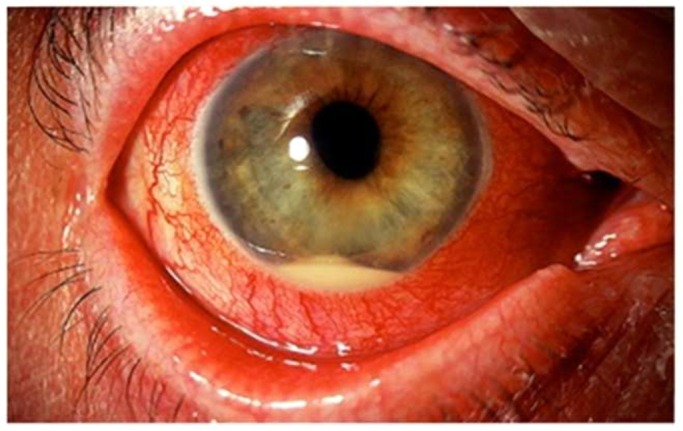

Vision in the right eye was limited to hand motions. An afferent pupillary defect was not noted. Intraocular pressure was elevated at 29 mmHg. The anterior segment examination of the right eye demonstrated a small corneal abrasion, shallow anterior chamber, and a mild hypopyon. A peripheral iridotomy was noted superiorly. The anterior segment findings limited visualization of the posterior pole. B-scan ultrasound demonstrated vitritis and no retinal detachment. A diagnosis of chronic post-operative endophthalmitis was made (Picture). Standard pars plana vitrectomy was completed without complication 76 days after her first symptoms. The vitrectomy fluid was opaque and brown. Samples of the vitreous cavity were sent to the laboratory for gram stain and microbiological studies. At the conclusion of the case, intravitreal injections of vancomycin, ceftazidime, and amphotericin B were administered. The KOH stain of right eye vitreous fluid showed numerous septate hyphae (Fig. 1). The patient was subsequently admitted for treatment 82 days after her first symptoms.

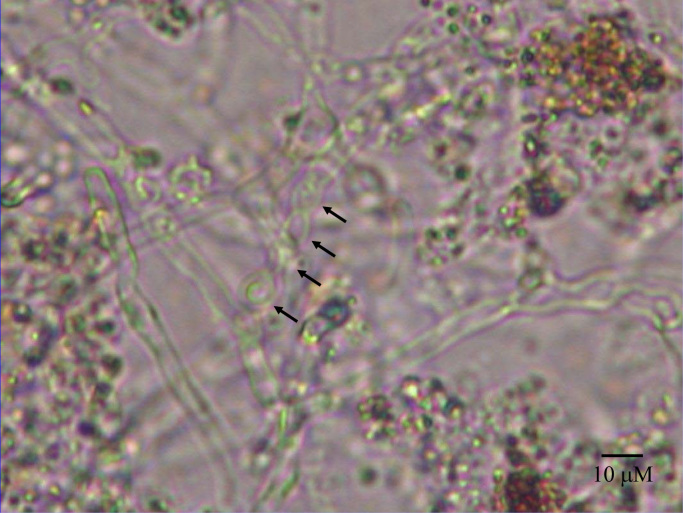

Fig. 1.

Direct KOH wet mount of ocular fluid. The ocular fluid contained brown granular material, hyphae measuring 6–8 μM in width and chains of arthroconidia (arrows), measuring 6×8 μM.

The patient was empirically treated with topical eye drops including Combigan (brimonidine and timolol) two times per day, polymyxin every six hours, Lumigan (Bimatoprost) daily, Durezol (difuprednate) every six hours. In addition, oral acetazolamide 250 mg twice daily, intravenous voriconazole 500 mg two times per day, and intravenous amphotericin B 3 mg/kg daily were given. Culture from the vitreous fluid grew a filamentous yeast-like mold that produced arthroconidia without blastoconidia. Urease was negative and sugar assimilation by API 20A identified the organism as Geotrichum species (API assimulation assay number 6042004), morphologically consistent with G. candidum. (Fig. 2). Automated blood cultures demonstrated no growth at 5 days, while the isolator blood culture demonstrated no growth at 21 days incubation. Following the positive vitrectomy, the patient returned for additional surgery.

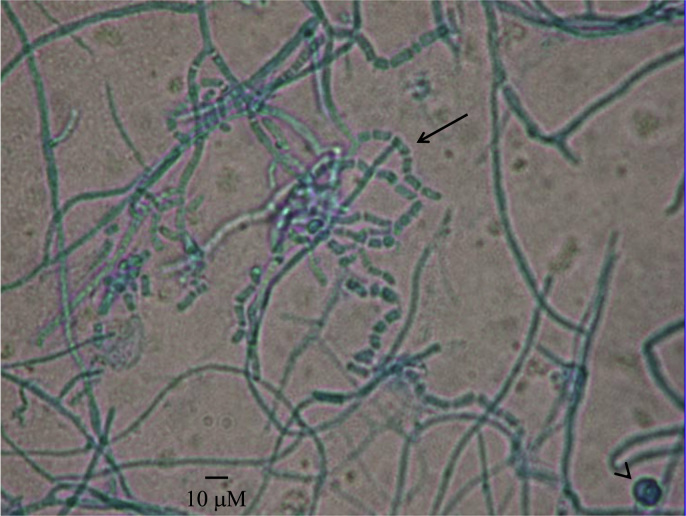

Fig. 2.

The organism on tape preparation from the Sabauraud dextrose agar stained with lacto-phenol-cotton-blue stain. The isolate grew as a septate, filamentous mycelium measuring 6–8 μM in width, with rare hlamydospores (arrowhead). The hyphae fragmented into chains of arthroconidia (arrow) and individual cells.

The posterior chamber intraocular lens was explanted and additional amphotericin B and voriconazole were administered via intravitreal injection. A dose of cefazolin was injected subconjunctivally. Additionally, fungal cultures from the right eye vitreous cavity and right eye intraocular lens collected at the time of the second surgery, did not demonstrate fungal or bacterial growth. After 9 days of intravenous voriconazole, it was changed to oral voriconazole 300 mg twice daily. Intravenous amphotericin B was given for 15 days and stopped after the serum voriconazole level became therapeutic (3.8 mcg/ml).

The susceptibility testing was performed using the Etest strip method, for which there were no CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) interpretations. Voriconazole MIC was 0.125 µg/mL, Itraonazole 6 µg/mL, Fluconazole 128 µg/mL, Amphotericin B 0.047 µg/mL. She was admitted for 23 days and discharged on 105 days after her initial onset of symptoms with multiple eye drops and treated with oral voriconazole 300 mg twice daily for three months.

Despite aggressive therapy, the patient's eye became painful and the vision deteriorated to light perception. She underwent enucleation of the right eye with a Medpor implant three months after antifungal treatment, 195 days after her first symptoms. The pathology demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation with abscess formation with extensive granulation tissue. A retinal detachment was present with adherence to the iris and ciliary body. No persistence of fungal elements was detected on extensive examination of the tissue sections.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published case of post-operative endophthalmitis caused by G.candidum. The genus Geotrichum is composed of 18 species. The most common species found in clinical specimens is G. candidum. G. candidum infections are overall very uncommon, presenting mainly as pulmonary or bronchopulmonary disease, but cutaneous, oral, and disseminated infections have also been noted [10]. Fewer than 100 cases have been reported between 1842 and 2006 [2], [5], [6], [7], [9], [11], [12], [13]. Recent cases reflect disease as opportunistic infections in at risk patient populations [14].

Other case reports of human disease attributed to Geotrichum spp. reflect organisms no longer considered Geotrichum spp. including Geotrichum clavatum (reclassified as Saprochaete clavate) and Geotrichum capitatum (reclassified as Blastoschizomyces capitatus), which are predominantly found in Europe (particularly in Italy) and in patients with leukemia [8].

G. candidum is a ubiquitous filamentous yeast-like fungus commonly isolated from soil, air, water, milk, silage, plant tissues, digestive tract in humans and other mammals [14], [15]. The young colonies of G. candidum are white, moist, yeast-like and easily picked up. Microscopically, it forms coarse true hyphae that segment into rectangular arthroconidia which vary in length (4–10 μm) [16]. The pattern of sugar assimilation, negative urease activity, and absence of blastoconidia produced along the hyphae, help to morphologically distinguish Geotrichum from Trichosporon spp. The findings for this patient’s isolate were consistent with a diagnosis of G. candidum as the etiologic agent.

There are very limited data on the activity of antimicrobial agents against G. candidum. Voriconazole has been shown to have the lowest MIC of the azole drugs [17], although amphotericin B containing compounds have been the most widely reported therapies [2], [5]. The susceptibility testing in our patient showed an amphotericin MIC of 0.04 mcg/ml, fluconazole 128 mcg/ml, itraconazole 6 mcg/ml, and voriconazole 0.125 mcg/ml. Even though she was given adequate treatment with 15 days of IV AmBisome and 3 months of voriconazole, her eye did not recover vision beyond light perception, despite histologic evidence of clearance of the infection.

The patient presented in this case did not have neutropenia, any documented underlying cancer or hematological malignancy, but instead had diabetes and surgical manipulation of the eye as the underlying risk factor for acquiring infection. Geotrichum endophthalmitis is a rare post operative fungal infection. It is probable that the organism was directly inoculated into the patient during the perioperative period surrounding the cataract procedure. Even with aggressive surgeries and systemic antifungal therapies, our patient failed to respond to treatment. Early recognition and treatment of this disease might have changed the patient’s outcome.

Conflict of interest

There are none

Ethical form

This patient expired. The patient's next of kin has no objection against publication.

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at:doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2015.11.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Fig. S1.

References

- 1.Larone D.H. Wiley; New York: 2011. Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sfakianakis A., Krasagakis K., Stefanidou M., Maraki S., Koutsopoulos A., Kofteridis D. Invasive cutaneous infection with Geotrichum candidum: sequential treatment with amphotericin B and voriconazole. Med. Mycol. 2007;45:81–84. doi: 10.1080/13693780600939948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henrich T.J., Marty F.M., a Milner D., Thorner a R. Disseminated Geotrichum candidum infection in a patient with relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia following allogeneic stem cell transplantation and review of the literature. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2009;11:458–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinic G.S., Greenspan D., MacPhail L.A., Greenspan J.S. Oral Geotrichum candidum infection associated with HIV infection. A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1992;73:726–728. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90019-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andre N., Coze C., Gentet J.C., Perez R., Bernard J.L. Geotrichum candidum septicemia in a child with hepatoblastoma. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004;23:86. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000107293.89025.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonifaz A., Vázquez-González D., Macías B., Paredes-Farrera F., Hernández M.A., Araiza J. Oral geotrichosis: report of 12 cases. J. Oral Sci. 2010;52:477–483. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagirdar J., Geller S.A., Bottone E.J. Geotrichum candidum as a tissue invasive human pathogen. Hum. Pathol. 1981;12:668–671. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(81)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girmenia C., Pagano L., Martino B., D’Antonio D., Fanci R., Specchia G. Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon species and Geotrichum capitatum in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective multicenter study from Italy and review of the literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:1818–1828. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1818-1828.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrdy D.B., Nassar N.N., Rinaldi M.G. Traumatic joint infection due to Geotrichum candidum. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;20:468–469. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hospenthal Rinaldi D.R., Michael G. Vol. 1. 2007. Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Mycoses (Infectious Disease) p. 428. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehy T.W., Honeycutt B.K., Spencer J.T. Geotrichum septicemia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1976;235:1035–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng K.P., Soo-Hoo T.S., Koh M.T., Kwan P.W. Disseminated Geotrichum infection. Med. J. Malays. 1994;49:424–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghamande A.R., Landis F.B., Snider G.L. Bronchial geotrichosis with fungemia complicating bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1971;59:98–101. doi: 10.1378/chest.59.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pottier I., Gente S., Vernoux J.P., Gueguen M. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: Geotrichum candidum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008;126:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miceli M.H., Diaz J.A., Lee S.A. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:142–151. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koneman E.W. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaragoza O., Mesa-Arango A.C., Gomez-Lopez A., Bernal-Martinez L., Rodriguez-Tudela J.L., Cuenca-Estrella M. Process analysis of variables for standardization of antifungal susceptibility testing of nonfermentative yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1563–1570. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01631-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]