Abstract

Objective

Electronic health records (EHRs) may contain infomarkers that identify patients near the end of life for whom it would be appropriate to shift care goals to palliative care. Discovery and use of such infomarkers could be used to conduct effectiveness research that ultimately could help to reduce the monumental costs for dying care. Our aim was to identify changes in the plans of care that represented infomarkers, which signaled the transition of care goals from non-palliative care goals to those consistent with palliative care.

Methods

Using an existing electronic health record database generated during a two-year, longitudinal study of 9 diverse medical-surgical units from 4 Midwest hospitals and a known group approach, we evaluated the patient care episodes for 901 patients who died (mean age=74.5±14.6 years). We used ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc tests to compare patient groups.

Results

We identified 11 diagnoses, including Death Anxiety and Anticipatory Grieving, whose addition to the care plan, some of which also occurred with removal of non-palliative care diagnoses, represent infomarkers of transition to palliative care goals. There were four categories of patients, those who had: no infomarkers on plans (n=507); infomarkers added on the admission plan (n=194); infomarkers added on a post admission plan (minor transitions, n=109), and infomarkers added and non-palliative care diagnoses removed on a post admission plan (major transition, n=91). Age, length of stay, and pain outcomes differed significantly for these four categories of patients.

Significance of Results

EHRs contain pertinent infomarkers that if confirmed in future studies could be used for timely referral to palliative care for improved focus on comfort outcomes and to identify palliative care subjects from data repositories for to conduct big data research, comparative effectiveness studies, and health services research.

Keywords: electronic health record, nursing, information marker, palliative care

Introduction

Electronic health records (EHRs) offer a treasure trove of patient information, including diagnoses, symptoms, treatments, and outcomes. Some data serve as biomarkers of prognosis or response to treatments (Feliu et al., 2011; Gagnon et al., 2013). It is possible that non-biologic EHR data could serve as infomarkers for other contexts such as care practices, but the idea of infomarkers has not been reported previously. Our study purpose was to identify infomarkers that appear within nursing care plan data for hospitalized patients prior to death that indicate care goals consistent with palliative care. Identification of such infomarkers is important as a first step for understanding how the context of care practices affect patient outcomes.

We define infomarkers as non-biologic data cues of a human state that are extracted from the EHR using a variety of techniques such as statistical or data mining techniques. Infomarkers can be used to project the possibility of a patient having or transitioning into a state associated with the infomarker. Although there are many ways the informaker term could be operationalized, in our context, the term is focused on EHR data patterns that serve as a cue for identifying a transition in goals of care from non-palliative care (disease or illness oriented or health restorative care) to palliative care (as mainly comfort-oriented care). For example, infomarkers indicative of a shift or need for a shift to palliative care goals among hospitalized patients could be used clinically to generate an EHR alert to initiate appropriate clinical services and inform appropriate use of diagnostic procedures and therapies (Smith et al., 2003). Such efforts could reduce the $2.8 trillion in healthcare costs (CMS, 2014) of which end-of-life (EoL) care now takes a disproportionate share of Medicare expenditures (Zhang et al., 2009) and veteran care (Yu, 2003). Another benefit of infomarkers is that data miners could use them to identify palliative care patients from big data repositories for comparative effectiveness and health services research. A novel idea is the possibility that infomarkers within the EHR could provide a way to extract data for research that could determine their additional benefits. Much like biomarkers demonstrate value for personalizing care, the EHR data might contain infomarkers that could guide care and be important for health services and big data science researchers.

An important but often overlooked component of the EHR is the nursing care data. When nurses document care plan data in the EHR every shift in standardized and interoperable format, the data can be analyzed to find any existing infomarkers. Using a data set with such data, the HANDS (Hands-on Automatic Nursing Data System) database, our specific aim was to identify changes in care plans that could be considered infomarkers of the transition from care goals from non-palliative care goals to those consistent with palliative care. We hypothesized that patients with infomarkers would have better pain outcomes, reflective of the palliative care focus.

Methods

Design

This study was a known group descriptive and comparative analysis of patients who died during a hospital admission as identified from an existing database with de-identified data. Our university’s Institutional Review Board determined the study did not involve human subjects.

The data were derived from a longitudinal study of nine diverse medical-surgical units from four hospitals in the Midwest over two years. A continuous patient stay in a single hospital unit defined a care episode, consisting of the care plans that nurses documented every shift into the HANDS EHR system. Nursing diagnoses were coded with North American Nursing Diagnosis Association-International (NANDA-I; NANDA International, 2003) terms. As part of their clinical routines, nurses updated diagnoses and interventions throughout the hospitalization as needed and rated outcomes each shift. At the end of a care episode, the nurse recorded the patient discharge disposition. Prior analysis of the dataset demonstrated that after 6-8 hours of training for each of the 787 nurses, there was a high level of compliance (78% to 92%) with updating the care plan each and every shift and moderately strong validity and reliability in their use of the NANDA-I terms (Keenan et al., 2012).

Sample

Nurses in nine medical surgical units entered a total of 42,403 episodes linked to 34,926 unique patients. In the current study, we examined the patient care during the episodes ending in death; therefore, we focused on a subset of 901 patients with a discharge disposition of “Expired.” These patients’ ages ranged from 20 to 105 years (mean=74.5±14.6). Gender and race were not required fields.

Procedures

Procedures are described in detail elsewhere where the investigators showed reliability and validity of nurses’ real-practice-world use of the terms in the care plans (Keenan et al., 2012). Briefly, all nurses received 6-8 hours of extensive training and then as part of their routine nursing practice, they recorded into the HANDS EHR system a series of care plans that reflected the care they gave to the patients each shift and the evolution of their conditions from unit admission until death. Each care plan documented the patient care during a shift, including all NANDA-Is, and each plan built on the previous one by the shift nurse adjusting (add or remove) NANDA-Is as needed. Therefore, the care plans were dynamic, representing the nursing care focus from shift to shift over the 12 or 24 months that the nine units from four hospitals participated in the original study.

Analysis

For the 901 patients who died, we examined the 9,196 care plans that were submitted each shift to the HANDS database by 567 of the 787 nurses. On average, there were 3.7±2.2 NAINDA-Is on these care plans. We first identified all NANDA-Is that were either added or removed from care plans during the hospitalization episode and examined their characteristics. Next we categorized the NANDA-Is as either consistent with palliative care goals or not (non-palliative care) based on their official NANDA-I definitions. We used the R statistical program for analysis. Using ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests, we compared groups of patients categorized by patterns of infomarkers for differences by age, length of stay, care plan elements, and pain outcomes. We set the statistical significance level as p<.05.

Results

Identification of Infomarkers

NANDA-I changes

We identified 515 shifts post admission where nurses added NANDA-Is. Among these, 102 shifts contained both NANDA-I additions and one or multiple NANDA-I removals during the same shift. We examined these 102 shifts first since they likely represented more radical changes in care than shifts with only NANDA-I additions. Of these, 85 (83%) had either Death Anxiety or Anticipatory Grieving added to the care plan. In addition, we found that the following NANDA-Is were added to 6 other care plans at the same time as non-palliative care NANDA-Is were removed: Readiness for Enhanced Family Coping (n=2), Ineffective Coping (n=2), or Acute Pain (n=2) (Table 1). In summary, 91/102 shifts indicated a transition to care goals consistent with palliative care. The remaining 11 reflected adjustments in care not related to a palliative transition.

Table 1. Identified Infomarkers Indicating Nursing Care Consistent with Palliative Care Goals.

| Informarker | NANDA-I Label |

|---|---|

|

NANDA-I(s) added at admission or later

in the patient’s hospital episode a |

|

|

NANDA-I(s) added as non-palliative

care NANDA-I(s) were removed during a patient’s hospital episode a |

|

|

Most frequent NANDA-I removals at

Major Transitions b |

|

continuous patient stay in a single hospital unit defined a care episode;

seven most frequent

We next examined the other shifts where only NANDA-I additions occurred. We identified, in addition to Death Anxiety, Anticipatory Grieving, Ineffective Coping, and Readiness for Enhanced Family Coping, five other NANDA-Is that could indicate care consistent with palliative care goals: Disabled Family Coping, Powerlessness, Readiness for Enhanced Coping, Risk for Powerlessness, and Spiritual Distress (Table 1). We did not consider the addition of either Acute Pain or Chronic Pain in the absence of simultaneous removal of non-palliative NANDA-Is as an indicator of care consistent with palliative care goals, since the mere addition of Acute or Chronic Pain to the care plan does not necessarily indicate transition to palliative care goals even near death. Among 413 shifts that had only NANDA-I additions, we found 116 shifts where one or more of the previously noted nine infomarkers were added.

Major vs Minor Transitions during a Care Episode

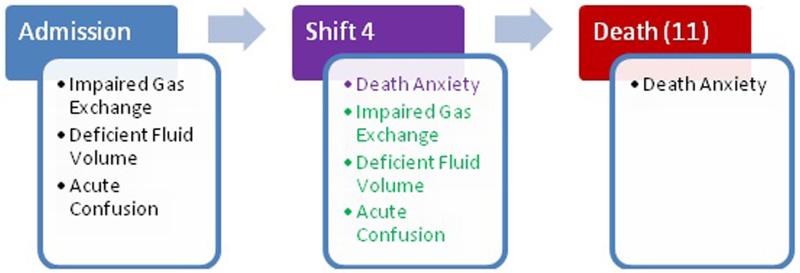

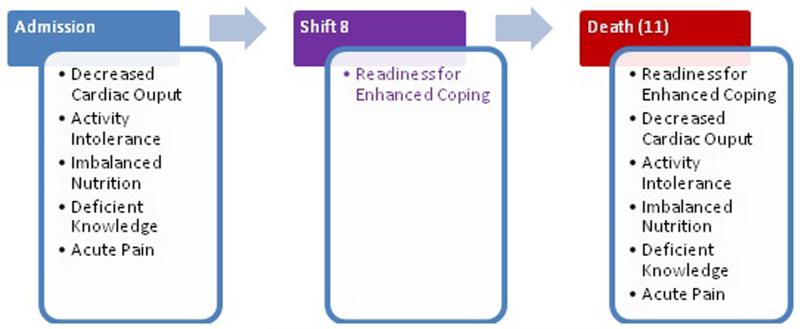

It appears that the 91 shifts with both NANDA-I additions and removals represent potentially major transitions in care shifting from non-palliative care to palliative care while the 116 shifts with only additions represent minor transitions attempting to incorporate care consistent with palliative care goals into the existing care regime. We examined the distribution of these transition points among the patients’ care episodes (Figure 1). No episode contained more than one major transition point. Similarly, a vast majority of the episodes with minor transitions contained only one transition point, but we found 6 episodes in which a minor transition co-occurred either with a major transition or another minor transition. In 4 episodes, there were both a major transition and a minor transition. In one episode, a single infomarker addition was followed by the addition of two infomarkers on the care plan on the next shift.

Figure 1.

In Figure 1, we show the outline of the care plan (NANDA-I only) for a couple of representative care episodes. The first sample episode contained a major transition, where a marker (labeled in purple) was added and multiple NANDA-Is (labeled in green) were removed. The transition block is labeled in purple. The second sample episode contained a minor transition, where a marker was added but no NANDA-I was removed.

In total, we identified 200 patients with care consistent with transitions to palliative care goals before they died. Of these, 91 patients had a major transition (4 of whom also had minor transitions), whereas the other 109 only had minor transition(s). The remaining 701 patients did not have a transition point consistent with palliative care goals, but 194 of those patients had one or more of the infomarkers on the care plan at admission, an indication that a patient was recognized as needing care consistent with palliative care goals at admission. The remaining 507 episodes did not have any of the infomarkers, which was 56% of the patients who died. In summary, we found four categories of patients based on infomarker analysis, those with (1) no infomarkers on any of the care plans; (2) infomarkers added on the admission care plan; (3) infomarkers added on a post admission care plan (minor transitions), (4) infomarkers added and non-palliative care NANDA-Is removed on a post admission care plan (major transition) (Table 2).

Table 2. Care Plan Comparison of 901 Patients Classified Using Infomarkers for Those who Died During Hospitalization.

| Episodesa with no transition |

Episodesa with transition | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative infomarker at admission |

No palliative infomarker |

Major transition |

Only minor transition(s) |

|||

| Number of patients | 194 | 507 | 91 | 109 | ||

| Patient age | 79.1 (12.2) | 72.0 (15.4) | 79.2 (10.8) | 74.3 (14.9) | <.001 | |

| Length of stay (Days) | 2.3 (2.2) | 3.8 (4.7) | 6.1 (5.5) | 6.6 (5.5) | <.001 | |

| Point of transition (Day) | 4.3 (3.8) | 4.6 (4.1) | .54 | |||

| Mean number of NANDA-Is at admission |

Pain | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.35 (0.48) | .93 |

| Non palliativeb |

0.28 (0.85) | 3.33 (2.00) | 3.55 (2.26) | 2.75 (1.81) | <.001 | |

| Mean number of NANDA-Is added post admission |

Pain | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.28) | 0.20 (0.43) | 0.24 (0.45) | <.001 |

| Non palliativeb |

0.05 (0.23) | 0.46 (0.90) | 0.69 (0.95) | 0.58 (0.92) | <.001 | |

| Non-palliative NANDA-I removed during episode |

0.05 (0.33) | 0.11 (0.50) | 3.14 (1.82) | 0.48 (1.29) | <.001 | |

| Non-palliative NANDA-Is (excluding pain) present at death |

0.26 (0.81) | 3.55 (2.07) | 0.60 (1.10) | 2.40 (2.07) | <.001 | |

| Pain outcome ratingsc |

initial | 3.40 (0.94) | 3.25 (1.04) | 3.47 (0.92) | 3.21 (1.10) | .36 |

| at death | 3.62 (1.30) | 3.24 (1.26) | 3.97 (1.08) | 3.43 (1.53) | .006 | |

continuous patient stay in a single hospital unit defined a care episode;

excludes Pain NANDA-Is;

Pain ratings could range from 1 (worst possible rating) to 5 (best possible rating, reflecting what a healthy person of the same age, sex, and cognitive ability would score)

Comparison of Patient Characteristics by the Four Categories

We next compared patients in the four categories (Table 2) and found a significant difference in patients’ average age (p<.001). Post hoc tests showed that patients, with infomarkers either at admission or with a major transition were on average significantly older than patients without any infomarker on their care plans (p<.001). Patients whose care plans only had minor transitions also were younger than patients with infomarkers at admission (p=.03) and showed a trend of being younger than patients with a major transition (p=.08).

The lengths of stay for patients in these four categories were significantly different from each other (p<.001). Post hoc tests revealed that patients with infomarkers of major or minor transitions had significantly longer stays than both the patients with infomarkers from admission and those patients with no infomarker at all (p<.001). Those patients with infomarkers from admission had shorter stays than those without an infomarker (p=.02). Examination of the time at which the transitions occurred for patients whose care plan had a major or minor transition showed that there was no significant difference in the timing of major and minor transitions points (p=.54). Furthermore, on average the transition occurred on day 5 of hospitalization whereas patients with no infomarker on average died by day 4.

Comparison of the NANDA-Is for these patients also revealed interesting information. Although there was very little difference in the presence of Acute or Chronic Pain NANDA-Is at admission among these four categories (p=.93), there was a clear difference in the number of NANDA-Is focused on non-palliative care and not related to pain or care consistent with palliative care goals at admission (p<.001). The patients whose plans of care contained infomarkers at admission had by far the fewest (p<.001) non-palliative care oriented NANDA-Is, while the difference between the other 3 categories was not significant.

Examination of NANDA-Is added post admission showed that patients with major or minor transitions had pain NANDA-Is added much more frequently than patients with an infomarker at admission (p<.001) or with no infomarker (p<.005). Patients whose care plan had infomarkers from the start had many fewer additions of non-palliative care oriented NANDA-Is post admission than the other patients (p<.001), but the difference between the other three categories was not statistically significant.

We found that patients whose care plan had a major transition had more NANDA-I removals than patients in the other three categories (p<.001). Patients with minor transitions had significantly more NANDA-I removals than the remaining two categories (p <.001). The average number of removals per patient (0.48) for patients with minor transitions, however, was more similar to those of patients with infomarkers from admission (0.05) and patients without an infomarker (0.11) than to patients with a major transition (3.14). Finally, at the time of patient death, the number of active non pain or palliative related NANDA-Is on the care plan for patients with a major transition was much lower than patients with no infomarker or with only minor transitions (p<.001) and not significantly different than patients with an infomarker from admission (p=.42).

The last two rows of Table 2 show the average pain ratings for patients in the four categories. There was no significant difference in the initial ratings (p=.36), but there was substantial difference in pain ratings at the time of death (p=.006). Post hoc testing shows that patients with major transition from non-palliative care to care consistent with palliative care goals had a significantly better pain outcome than patients with no infomarker (p=.009). Comparing the initial and final pain ratings in each category, we see clear improvement for patients with a major transition to care consistent with palliative care goals, but no improvement for patients without an infomarker.

Palliative Transitions

We examined the four categories of patients and the timing of changes in the care plans (Table 3). For the majority of the pain NANDA-Is, additions post admission occurred at the transition points. For the NANDA-Is not related to pain or infomarkers, on the other hand, almost all were placed on the care plans preceding the transition points, not afterward. Table 3 also shows that there were very few NANDA-I removals outside the transition points.

Table 3. Timing of NANDA-I Changes: Averages for Patients with Major or Minor Transitions.

| Patients with a major transition (n=91) |

Patients with only minor transitions (n=109) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of pain NANDA-Is added |

Pre transition (post admission) | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.07 (0.26) |

| At transition | 0.12 (0.33) | 0.17 (0.37) | |

| Post transition | 0 | 0 | |

| Average number of non- palliative NANDA-Is added |

Pre transition (post admission) | 0.63 (0.90) | 0.53 (0.88) |

| At transition | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.13) | |

| Post transition | 0.05 (0.27) | 0.03 (0.16) | |

| Average number of NANDA-Is removed |

Pre transition | 0.13 (0.60) | 0.21 (0.89) |

| At transition | 2.87 (1.73) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Post transition | 0.13 (0.48) | 0.27 (0.75) | |

Discussion

We are the first to identify EHR infomarkers that suggest care consistent with palliative care goals for hospitalized EoL patients. In a known sample of 901 patients who died, 43.7% of the patients had infomarkers on their care plans that were consistent with palliative care goals. Specifically, nine NANDA-I terms whose addition to care plans and two NANDA-Is whose addition along with simultaneous removal of other NANDA-Is represent either a major or minor transition point shifting to care consistent with palliative care goals before death. Infomarkers indicative of care consistent with a palliative care focus also were present on the admission care plan for some patients. Comparison of NANDA-Is at admission as well as types and timings of NANDA-I changes post admission between four categories of patients provide compelling evidence that these infomarkers indeed indicate care consistent with palliative care goals. Older patients were significantly more likely to have an infomarker at admission or a major transition than younger patients. Younger patients were more likely to have minor transitions than infomarkers at admission. Patients with longer lengths of stay were significantly more likely to have major or minor transitions than those with no transitions or infomarkers at admission. Finally, pain outcomes were significantly better for patients with major transitions than those without infomarkers indicative of care consistent with a palliative care focus.

Patient care at the EoL is often challenging due to uncertainties regarding when non-palliative disease or illness oriented or health restorative focused care should transition to palliative comfort-focused care (Goodman, Esty, S. Fisher, & Chang, 2011; Mack, Weeks, Wright, Block, & Prigerson, 2010). Consequently, many efforts are expended on futile and costly care at the EoL (Goodman, et al., 2011; Mack, et al., 2010) with interventions and treatments that fall short of addressing pain and suffering for the patient and family prior to death (Cruz, Camalionte, & Caruso, 2014). In many instances patients suffer through an undignified death as a result of the futile life-prolonging intensive care (Goodman, et al., 2011; Mack, et al., 2010). Therefore, our finding that pain outcomes were significantly better for patients with major transitions than those without infomarkers supports validity of our findings. The presence of a major transition as indicated by the addition of infomarkers and the removal of non palliative NANDA-Is signifies that the care team is moving away from disease or illness oriented or health restorative focused care to an emphasis on comfort care for the dying patient.

Perhaps most exciting about our discovery of the infomarkers in the HANDS EHR and their use to demonstrate transitions in EOL care from acute to a palliative focus is the potential importance for big data science using nursing care data. We have only scratched the surface in the analysis of shift-to-shift changes in the care plans, but the identified infomarkers support the relevance of this type of analysis of practice-based data. If confirmed with further research, infomarkers provide a potentially cost efficient way of identifying patients for palliative care studies using EHR data. Our findings may precipitate further research using big data from EHRs to drive enhanced care practices for the dying and to help better direct government spending for EoL care.

Even though our finding of the infomarkers is novel and important, some limitations detracted from them. First, it is not clear what the medical care plan was for the 901 patients we studied. Because of the nature of our database, we are not able to determine if the addition, removal, or retention of the patient’s nursing diagnoses on the care plans were made independent of or reactive to changes in the medical care goals. It is also not clear from data available for this study who was first to identify that the patient was at the EoL, the nurses or other health professionals.

In summary, we identified infomarkers that indicate care consistent with palliative care goals was the dominant goal of nursing care. Using these infomarkers, four categories emerged, patients: with palliative care implemented from admission, with a major transition shifting from non-palliative care to care consistent with palliative care goals, with minor transitions incorporating care consistent with palliative care goals along with non-palliative care, and without such palliative care indicators. Even in a small sample, there is evidence suggesting that focusing on care consistent with palliative care goals and removing unnecessary non-palliative care near the patient death might lead to better patient outcomes. EHRs contain pertinent infomarkers that if confirmed in future studies could be used for timely referral to palliative care for improved focus on comfort for EoL patients. These infomarkers could also be used to identify palliative care subjects from data repositories for big data, comparative effectiveness, and health services research.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by Grant Number 1R01 NR012949 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Nursing Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute for Nursing Research. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy. The authors thank Veronica Angulo for clerical assistance.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

The HANDS software that was used in this study is now owned and distributed by HealthTeam IQ, LLC. Dr. Gail Keenan is currently the President and CEO of this company and has a current conflict of interest statement of explanation and management plan in place with the University of Illinois at Chicago.

References

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Health Expenditures Projections 2012-2022. 2014 Retrieved April 24, 2014, from www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics.

- Cruz VM, Camalionte L, Caruso P. Factors Associated With Futile End-Of-Life Intensive Care in a Cancer Hospital. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1049909113518269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliu J, Jimenez-Gordo AM, Madero R, Rodriguez-Aizcorbe JR, Espinosa E, Castro J, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103(21):1613–1620. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon B, Agulnik JS, Gioulbasanis I, Kasymjanova G, Morris D, MacDonald N. Montreal prognostic score: estimating survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer using clinical biomarkers. British Journal of Cancer. 2013;109(8):2066–2071. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DC, Esty AR, Fisher ES, Chang C. Trends and Variation in End-of-Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries with Severe Chronic Illness. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice; 2011. S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan GM, Yakel E, Yao Y, Xu D, Szalacha L, Tschannen D, et al. Maintaining a Consistent Big Picture: Meaningful Use of a Web-based POC EHR system. Inernational Journal of Nursing Knowledge. 2012;23(3):119–133. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-3095.2012.01215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NANDA International . Nursing diagnoses: Definition and classification 2003-2004. Philadelphia, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Coyne P, Cassel B, Penberthy L, Hopson A, Hager M. A High-Volume Specialist Palliative Care Unit and Team May Reduce In-Hospital EoL Care Costs. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6(5):699–705. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. EoL Care: Medical Treatments and Costs by Age, Race, and Region. 2003 http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts/IIR_02-189.htm.

- Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with EoL conversations. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(5):480–488. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]