Summary

During bacterial infections, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signals through the MyD88-dependent pathway to promote rapid pro-inflammatory responses, but also signals via the TRIF-dependent pathway, which promotes Type-I interferon responses and acts with MyD88 signaling to potentiate inflammatory cytokine production. Bacteria can inhibit the MyD88 pathway, but if the TRIF pathway is also targeted is unclear. We demonstrate that, in addition to MyD88, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis inhibits TRIF signaling through the Type III secretion system effector YopJ. Suppression of TRIF signaling occurs during dendritic cell (DC) and macrophage infection, and prevents expression of Type-I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines. YopJ-mediated inhibition of TRIF prevents DCs from inducing Natural Killer cell production of antibacterial interferon-γ. During infection of DCs, YopJ potently inhibits MAPK pathways but does not prevent activation of IKK- or TBK1-dependent pathways. This singular YopJ activity efficiently inhibits TLR4 transcription-inducing activities, thus illustrating a simple means by which pathogens impede innate immunity.

Introduction

Innate sensing of bacteria is mediated by proteins called Toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLRs detect common microbial features known as pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and activate signaling networks to promote inflammatory gene expression leading to clearance of the invading microbe (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004)). Pathogenic bacteria, however, have evolved mechanisms to inhibit TLR signaling pathways (Baxt et al., 2013)). In particular, bacteria often target signaling downstream of TLR4, a receptor for bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Poltorak et al., 1998)). TLR4 activates two distinct signaling networks: the MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways (Oda and Kitano, 2006)). LPS sensing by TLR4 at the plasma membrane promotes the MyD88-dependent rapid activation of the transcription factors AP-1 and NF-ĸB (Kawai et al., 1999)). TLR4 is then delivered to endosomes, where it signals through the TRIF pathway to induce late-phase AP-1 and NF-ĸB activation. TRIF also induces the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 (IRF3), an important regulator of Type-I interferon (IFN) (IFNα and β) production (Fitzgerald et al., 2003b; Yamamoto et al., 2003)). TRIF-dependent signaling acts with the MyD88-dependent pathway to promote inflammatory cytokine production (Hirotani et al., 2005)), but can be differentiated from MyD88-dependent signaling by this latter activity of IRF3 activation and Type-I IFN production.

Most investigations into bacterial strategies to disrupt TLR4 have focused on their ability to block MyD88-dependent signaling (Rosadini and Kagan, 2015)). In contrast, the extent to which bacteria interfere with TRIF-dependent responses is unclear. Recent work indicates that TRIF regulates immunity to bacterial infections in mice (Broz et al., 2012; Gurung et al., 2012; Jeyaseelan et al., 2007; Power et al., 2007; Rathinam et al., 2012)). TRIF induced Type-I IFN also promotes the ability of dendritic cells (DCs) to activate natural killer (NK) to release IFNγ, a cytokine with antibacterial activity (Fernandez et al., 1999; Zanoni et al., 2013)). Together, these findings indicate that TRIF regulates antibacterial processes, which prompted us to examine if pathogenic bacteria have developed strategies to inhibit TRIF signaling.

Pathogenic Yersinia spp., including Y. pestis, Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis (Yptb), inhibit innate immune responses. Examples of Yersinia-encoded immune evasion strategies include modifying their LPS structure to be less detectable by TLR4 (Montminy et al., 2006)) and secreting effector proteins into host cells via a Type-III secretion system (Trosky et al., 2008)). Notably, the Type III effector YopJ acetylates proteins within the MyD88 signaling network leading to blockade of NF-ĸB and AP-1 activation, and also phagocyte death (Mittal et al., 2006; Monack et al., 1997; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Palmer et al., 1998; Paquette et al., 2012; Schesser et al., 1998)). It is unclear whether the actions of YopJ or any other Yersinia effector influences the TRIF pathway induced by TLR4. Interestingly, TRIF is required for the protection of mice from Y. enterocolitica infection (Sotolongo et al., 2011)), suggesting a possible need to evade TRIF-mediated signaling events. Thus, we hypothesized that Yersinia spp. may harbor mechanisms that would inhibit the TRIF-dependent pathway and investigated the ability of one of the Yersinia spp. to suppress TRIF signaling and Type-I IFN production in immune cells.

In this study, we report that Yptb inhibits TRIF-dependent responses, including Type-I IFN expression, in DCs and macrophages via a YopJ-dependent mechanism. Surprisingly, we find that YopJ does not inactivate proteins within the TRIF-IRF3 axis or IκB kinase (IKK)-dependent processes in DCs, but rather specifically inhibits mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and AP-1 activation. We show that inhibition of MAPK pathways is sufficient to inhibit expression of a broad range of cytokines induced by TLR4. Further, YopJ-dependent inhibition of TRIF signaling impairs the ability of DCs to induce IFNγ production by NK cells. These data reveal that Yptb specifically targets MAPKs during infection, and that this singular activity is sufficient to prevent induction of the TLR4-dependent transcriptional program.

Results

Yptb suppresses TRIF-dependent gene expression in macrophages and DCs

To determine if Yptb suppresses TRIF-dependent signaling, murine bone marrow derived DCs (BMDCs) were infected with Yptb strain Yp2666 and a Yp2666 strain lacking its virulence plasmid. The strain lacking the virulence plasmid, which encodes the Type-III secretion system and Yop effector proteins, is herein referred to as “plasmid-.” Infected cells were examined for MyD88 or TRIF-dependent gene expression (Fig. 1A). As expected, Yp2666 infected cells induced minimal expression of Il6, a gene that requires MyD88 signaling for full induction. In contrast, cells infected with the plasmid- strain elicited robust expression of this gene. Compared to the plasmid- strain, Yp2666 also repressed expression of three genes considered to be activated downstream of TRIF, Ifnb1 (IFNβ), Cxcl10, and Rsad2 (Fitzgerald et al., 2003a; Yamamoto et al., 2003)) (Fig. 1A). This observation suggested that virulence plasmid encoded genes were important for blocking TRIF responses. Because YopJ suppresses innate immune responses, we examined a yopJ null mutant generated in the Yp2666 background, and found that this mutant phenocopied the plasmid- strain for its inability to block Ifnb1, Cxcl10 and Rsad2 expression (Fig. 1A). YopJ-dependent inhibition of Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Rsad2 was observed at both high (100) and low (20) MOIs (Fig. 1A and S1A). These data suggest that, in addition to blocking cytokine expression, YopJ has the ability to block IFN expression.

Figure 1.

Yptb inhibits TRIF-dependent gene expression via a YopJ-dependent mechanism. BMDCs (A, C, and D), iBMDMs (B) were infected with strains indicated at an MOI of 100. Gene expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by qPCR at times indicated or 2 hrs post infection (C). Uninfected cells (Con) were included in all experiments. Analysis of cell viability was performed by flow cytometry using propidium iodide and annexin V stains at times indicated for BMDCs (E) or iBMDMs (F) and was performed in parallel with (A) or (B), respectively. For gene expression analysis, bars represent the average and error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate readings from one representative experiment of three. Relative statistics were calculated using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. See also figure S1.

We also determined if YopJ was required for blocking TRIF signaling in macrophages. Immortal bone marrow derived macrophages (iBMDMs) were infected with Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant and analyzed for gene expression. YopJ-dependent inhibition of Il6, Ifnb1, Cxcl10 and Rsad2 was observed in these cells (Fig. 1B), and in primary BMDMs (Fig. S1B). Thus, Yptb suppresses TRIF-dependent responses in macrophages in a YopJ-dependent manner.

To verify the role for YopJ in blocking expression of the genes examined, BMDCs were infected with yopJ mutants harboring an empty plasmid vector or a vector expressing yopJ or yopP (the yopJ homolog from Y. enterocolitica). Expression of yopJ or yopP complemented the yopJ mutant for the ability to block Il6 and Ifnb1 expression in BMDCs, while the strain containing the empty vector could not (Fig. 1C). YopJ is an acetyltransferase whose enzymatic activity is required for its immune-evasion activities (Mittal et al., 2006; Mukherjee et al., 2006)). Therefore, we examined the requirement for YopJ catalytic activity in blocking gene expression. BMDCs were infected with Yptb parent strain, Yp32777 and a strain harboring a yopJ mutant deficient in a critical active site residue, C172A (yopJC172A). Whereas Yp32777 suppressed Il6, Ifnb1, CXCL10, and Rsad2 expression, the strain expressing yopJC172A was unable to block expression of these genes (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data establish that YopJ and its catalytic activity are required for blocking the expression of all genes examined.

Potentially, Yptb interferes with all signaling pathways examined by inducing YopJ-dependent cell death. To address this, we performed experiments where bacteria-induced gene expression was examined side-by-side with cell viability. Cell viability was examined by flow cytometry using the stains annexin V (AV) (which labels apoptotic cells) and propidium iodide (PI) (which labels necrotic cells). Cells that stain negative for both stains are considered viable. Infection of BMDCs with the parent strain Yp2666 or the yopJ null mutant resulted in only a slight increase in AV/PI staining over uninfected control cells at 1 and 2 hours (hr) post-infection (Fig. 1E and S1C). Importantly, throughout the assay the majority of cells (>85%) were negative for AV/PI staining (i.e. healthy cells), and the observed staining pattern was not different between Yp2666 and yopJ mutant infections (Fig. 1E and S1C). Thus, loss of cell viability is not likely to be responsible for the YopJ-dependent differences in gene expression observed in BMDCs at these time points.

Cell viability was also assessed for Yptb infected macrophages. A time-dependent increase in cell death was observed, with YopJ-dependent death being most apparent 2 hr post-infection (Fig. 1F and S1D). Similar results were also observed for infection of primary BMDMs (Fig. S1E). These data indicate YopJ-dependent effects on cell viability are most apparent in macrophages, as opposed to DCs, which is consistent with prior work (Brodsky and Medzhitov, 2008)).

Inhibition of gene expression by YopJ is independent of YopJ-induced cell death

YopJ-induced cytotoxicity proceeds via a RIPK1/caspase 8 or RIPK3-dependent pathway leading to caspase-1 activation and subsequent cell death (Philip et al., 2014; Weng et al., 2014)). To examine further if YopJ-induced activation of caspases and death-related pathways plays a role in blocking innate immune signaling, we infected RIPK3-deficient BMDCs treated with a pan-caspase inhibitor (zVAD-fmk). These conditions render cells resistant to YopJ-induced death (Philip et al., 2014; Weng et al., 2014)). RIPK3-deficient cells treated with zVAD-fmk were protected from death induced by YopJ, compared with these cells treated with vehicle only or wild-type (WT) BMDCs treated with either vehicle or zVAD-fmk (Fig. 2A and S2A). Despite the inability of Yp2666 to induce any detectable cytotoxicity in RIPK3-deficient cells treated with zVAD-fmk, YopJ-dependent inhibition of Il6 and Cxcl10 expression was observed (Fig. 2B). To complement these studies, we examined RIPK3/caspase 8 double mutant BMDCs, which are resistant to YopJ-mediated cell death (Philip et al., 2014; Weng et al., 2014)), as confirmed by AV/PI staining at 4 hrs post infection (Fig. 2C and S2B). Under these conditions, YopJ-dependent inhibition of gene expression remained (Fig. 2D). These collective observations establish that YopJ-dependent cell death is not required for the ability of Yptb to prevent TRIF-dependent gene expression in BMDCs.

Figure 2.

YopJ inhibits TRIF-dependent gene expression independent cytotoxicity. Cell viability (A, C, and F) and gene expression (B, D, and E) of WT (A and B) and Ripk3−/− BMDCs (C and D) Ripk3/Caspase 8−/− BMDCs, or (E and F) Ripk3−/− BMDMs. Cells were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or pan-caspase inhibitor (zVAD-fmk) prior to infection at an MOI of 100. Gene expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by qPCR at 4 hr (B and D) or 3 hr (E) after infection. Uninfected cells (Con) were used as a negative control. Analysis of cell viability was performed by flow cytometry using propidium iodide and annexin V staining. For gene expression analysis, bars represent the average and error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate readings from one representative experiment of two (B and E) or three (D). Relative statistics were calculated using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. See also figure S2.

The contribution of YopJ-induced cytotoxicity toward gene expression in macrophages was also examined in RIPK3-deficient BMDMs treated with vehicle control or with zVAD-fmk. Yp2666 retained the ability to block Il6 or Rsad2 expression in these cells, by a mechanism dependent on YopJ (Fig. 2E). Notably, the cytotoxic actions of YopJ were readily apparent in macrophages, as vehicle treated RIPK3-deficient BMDMs infected with Yp2666 exhibited a decrease in viability, as compared with yopJ mutants at 3 hr post infection (Fig. 2F and S2C). Treatment of these cells with zVAD-fmk was protective against YopJ-induced cell death compared to cells treated with vehicle control (Fig 2F and S2C). Together, these data demonstrate the ability of YopJ to block gene expression occurs independently of any cell death programs activated during infection.

YopJ suppresses MyD88- and TRIF-dependent transcriptional responses downstream of TLR4

Genes, such as Cxcl10 or Il6, can be induced by several receptors. To determine the mechanism by which YopJ inhibits these genes, we defined the receptor(s) required for gene expression in BMDCs, with a focus on TLR4. We compared WT and TLR4-deficient BMDCs for responses to infection with Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant. Only WT cells were capable of responding to the yopJ mutant whereas TLR4-deficient cells could not (Fig. 3A). Neither WT nor TLR4-deficient cells induced Il6 or Cxcl10 expression in response to Yp2666 infection. These data demonstrate that the TLR4 pathway is responsible for induction of gene expression in response to Yptb in BMDCs.

Figure 3.

YopJ suppresses MyD88 and TRIF transcriptional responses downstream of TLR4. Gene expression induced during Yp2666 infection of WT vs TLR4-deficient (Tlr4) (A), MyD88-deficient (Myd88) (B) or Trif-deficient (Ticam1) BMDCs (C). BMDCs were infected with strains indicated at an MOI of 100. Gene expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by qPCR at times indicated. Uninfected cells (Con) were used as a negative control. Bars represent the average and error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate readings from one representative experiment of two (B) or three (A and C). Relevant statistics were calculated using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

Il6 and Ifnb1 require contribution of MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways downstream of TLR4 for full induction (Yamamoto et al., 2003)). Inhibition of MyD88-dependent signaling by YopJ may therefore affect expression of TRIF-dependent genes indirectly. To address this possibility, we performed infections in MyD88-deficient cells, which only permit signaling via the TRIF pathway. YopJ retained the ability to block Il6 and Cxcl10 transcription in MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Fig. 3B). As expected, TRIF (Ticam1)-deficient BMDCs were unable to induce Cxcl10 expression in response to Yp2666 or yopJ mutant infection (Fig. 3C). These collective data indicate YopJ can target the TRIF pathway downstream of TLR4 directly, and not as an indirect consequence of inhibiting MyD88 signaling.

YopJ does not interfere with TRIF-dependent IRF3 activation

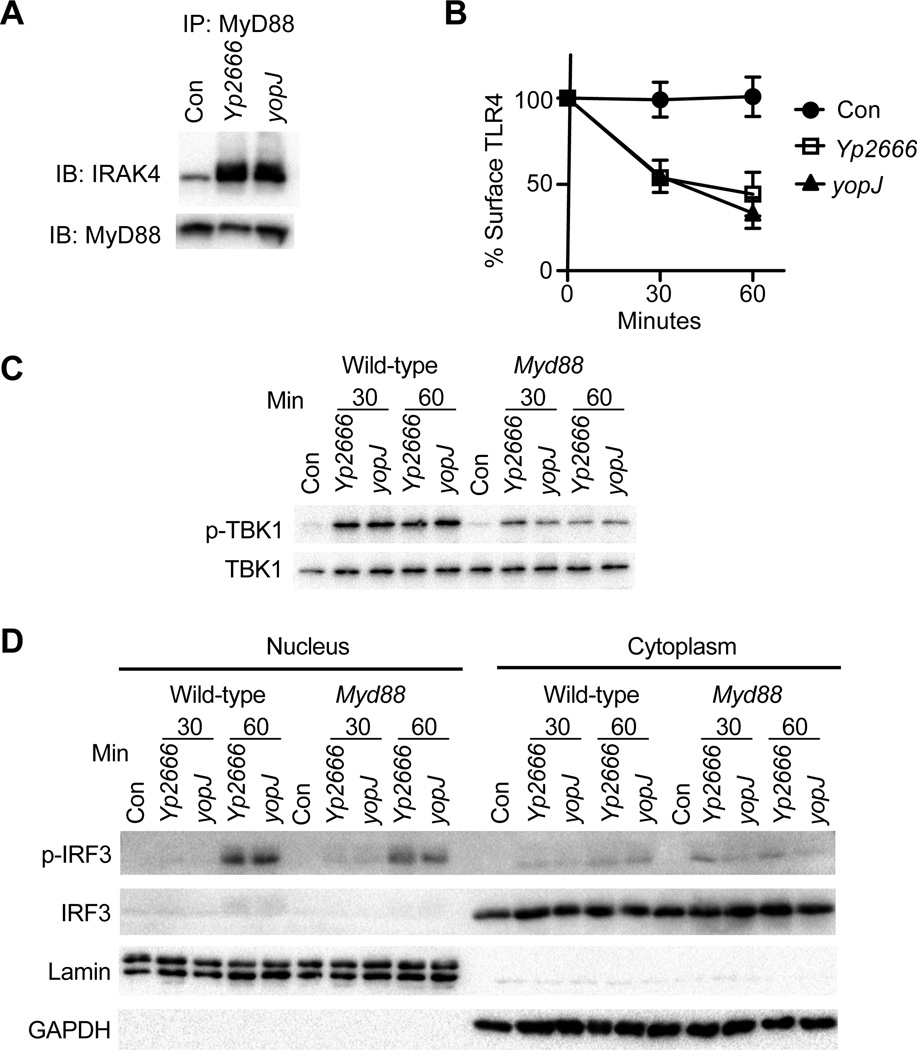

To determine if components of the TRIF pathway are inactivated by YopJ, we interrogated stages of the pathway starting with TLR4 activation. Normally, upon stimulation with LPS, TLR4 initiates the assembly of a protein complex called the myddosome, which is a supramolecular organizing center (SMOC) that coordinates all signals necessary for inflammatory cytokine expression. This complex consists of the adaptors TIRAP and MyD88, and IRAK family kinases (Kagan et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2010; Motshwene et al., 2009)). To assess effects of YopJ on TLR4 activation, we monitored myddosome formation during Yp2666 or yopJ mutant infection in iBMDMs. Equal levels of IRAK4 were co-immunoprecipitated with MyD88 from iBMDMs infected with Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant (Fig. 4A), suggesting YopJ does not interfere with TLR4 activation. Next, to signal via the TRIF pathway, TLR4 must be internalized where it can activate TRIF from endosomes (Kagan et al., 2008; Zanoni et al., 2011)). To examine if TLR4 endocytosis was affected by YopJ, we monitored loss of TLR4 surface expression. TLR4 was endocytosed equally in iBMDMs infected with Yp2666 or a yopJ mutant (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

YopJ does not block TRIF-dependent IRF3 activation. iBMDMs were infected with strains indicated and monitored for Myddosome formation (A) or TLR4 endocytosis (B). Myddosome formation was assessed 1 hr after infection. TLR4 endocytosis was examined by flow cytometry. In (A) and (B) uninfected cells (Con) served as a negative control. WT or Myd88-deficient BMDCs (Myd88) were infected with strains indicated and monitored for TBK1 phosphorylation (C) and IRF3 phosphorylation and p-IRF3 nuclear translocation (D). Phosphorylation of TBK1 was assessed by immunoblot of cell lysates with a phospho-S172 specific antibody. Total TBK1 was monitored by immunoblot with an antibody specific for total TBK1. IRF3 activation was assessed after infection of BMDCs by isolating nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions and immunoblotting with antibodies specific for phospho-IRF3 or total IRF3. Immunoblotting for Lamin and GAPDH served as controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. Data are one representative of two independent experiments.

Endosomal TLR4 promotes the TRIF-dependent activation of the IKK family member TBK1, a kinase that activates IRF3 and induces IFNβ expression (Fitzgerald et al., 2003a)). As YopJ inactivates IKKs (Mittal et al., 2006; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2005)), it was possible YopJ interferes with TRIF signaling by preventing TBK1 activation. To address this possibility, BMDCs were infected with Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant and examined for TBK1 phosphorylation, and phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3. No YopJ-dependent effects on TBK1 phosphorylation, IRF3 phosphorylation or p-IRF3 nuclear translocation were observed in WT or MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Fig. 4C, D). Thus, despite the ability to block TRIF-dependent gene expression, YopJ cannot interfere with TLR4 activation, endocytosis, or the activation of IRF3.

YopJ inhibits gene expression by blocking MAP kinase pathways in BMDCs

We considered the possibility that YopJ inhibits TRIF-dependent gene expression by blocking IKKs, which are necessary for the activation of NF-ĸB. We therefore assessed degradation of IĸBα during infection of BMDCs as a readout for IKK activity. No YopJ-dependent effects on the rate or extent of IĸBα degradation were observed, even when IĸBα resynthesis was blocked through the use of cycloheximide (Fig 5A). This finding was surprising, as previous studies in BMDMs reported that YopJ prevents IĸBα degradation (Zhang et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2005)). Complementary assays to assess nuclear translocation of the NF-ĸB subunit p65 also revealed no YopJ-dependent effects in WT or MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these data suggest IKK activity is not affected by YopJ during the first hr of infection of BMDCs.

Figure 5.

YopJ inhibits cytokine production in BMDCs by blocking MAPKs. (A) WT BMDCs or (B and C) WT and MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Myd88) were infected with strains indicated at MOI 100 and monitored for IĸBα degradation (A), p65 nuclear translocation (B), MKK phosphorylation (C), and MAPK phosphorylation (D) at times indicated. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and immunoblotting for Lamin and GAPDH verified nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively (A). Whole cell lysates were collected and immunoblotting GAPDH or total MAPKs served as loading controls (A, C and D). BMDCs were pretreated with DMSO (vehicle control), CHX (50 ng/ml) or specific inhibitors for ERK, p38 or, JNK or a combination of inhibitors at the time of infection (A) or prior to infection with strains indicated (E and F). At 90 minutes post infection, gene expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by qPCR (E and F). Uninfected cells served as a negative control in all experiments. Bars represent the average and error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate readings from a one representative experiment. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Relevant statistics were calculated using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. See also figure S3 and Table S1.

In addition to IKK and TBK1, TRIF signaling activates MAPK and the downstream transcription factor AP-1. To examine the influence of YopJ on MAPK pathways, we assessed phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38, and their upstream map kinases kinases (MKKs), MEK1/2, MKK3/6, MKK4, and MKK7, during infection. YopJ-dependent inhibition of all MKKs and MAPKs was observed in either WT or MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Fig 5C and D). These data establish that YopJ blocks TRIF-dependent MAPK activation. Inhibition of MAPK pathways was dependent on the catalytic activity of YopJ, as a strain expressing yopJC172A was incapable of suppressing MAPK activation (Fig. S3A). To examine the functional significance of YopJ inhibition of MAPK pathways, we examined activation of AP-1. Interestingly, the parental strain Yp32777 suppressed phosphorylation of the AP-1 subunit c-Jun, whereas the strain expressing yopJC172A could not (Fig. S3B). As was observed for MAPK activation, YopJ-dependent AP-1 inhibition was also observed in MyD88-deficient BMDCs (Fig. S3B). Importantly, AP-1 inhibition by Yp32777 occurred at times where no difference in p65 nuclear translocation could be observed between Yp32777 and yopJC172A mutant infections (Fig. S3B). Similar results were obtained with MOI of 20 (Fig. S3C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the enzymatic activity of YopJ prevents MAPK-mediated activation of AP-1 induced by both MyD88 and TRIF during times when neither IKKs nor TBK1 are inactivated.

Potentially, Yptb requires no activity other than inhibiting MAPKs to dismantle TLR4-induced gene expression. Inhibiting MAPK activation by alternative means should therefore abolish TLR4-induced gene expression. We treated WT and MyD88-deficient BMDCs with MAPKspecific pharmacological inhibitors and assessed gene expression in response to infection. Compared with the vehicle control, inhibition of the p38 (but not ERK) pathway suppressed expression of all genes examined in response to the yopJ mutant to levels similar to those elicited by Yp2666 infection (Fig. 5E). Although inhibition of the JNK pathway suppressed Ifnb1 expression, it had no effect on Cxcl10 or Il6 expression (Fig. 5E). Because YopJ inhibits all three MAPK pathways, the effects of combinations of inhibitors on gene expression were examined. Combinations including ERK+p38, p38+JNK, or all three inhibitors combined, suppressed Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Il6 expression in response to the yopJ mutant (Fig. 5F). The combination of ERK and JNK inhibitors also suppressed Ifnb1 expression, but to a lesser degree than combinations which inhibited p38 (Fig. 5F). Large scale transcriptional analysis of BMDCs treated with vehicle or a combination of three MAPK inhibitors revealed that YopJ blocked expression of all genes examined (Table S1 and Fig. S5D). Likewise, inhibition of MAPK pathways suppressed TLR4-inducible genes in response to the yopJ mutant to levels similar to those observed with Yp2666 infection of vehicle treated BMDCs (Table S1 and Fig. S3D). To complement these studies, we compared gene expression in WT and p38α-deficient BMDMs (Kim et al., 2008)). p38α deficiency reduced expression of Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Rsad2 in response to the yopJ mutant to levels similar to those observed with Yp2666 infection (Fig. S3E). p38α-deficient BMDMs were not impaired for Il6 expression in response to the yopJ mutant infection (Fig. S3E), possibly as a result of the remaining activity of other p38 isoforms in these cells (Fig. S3F). These data support the idea that inhibition of MAPKs by YopJ is sufficient to inhibit MyD88 and TRIF-dependent gene expression in BMDCs.

YopJ inhibits DC mediated activation of NK cells, but has a minor overall influence on infection in vivo

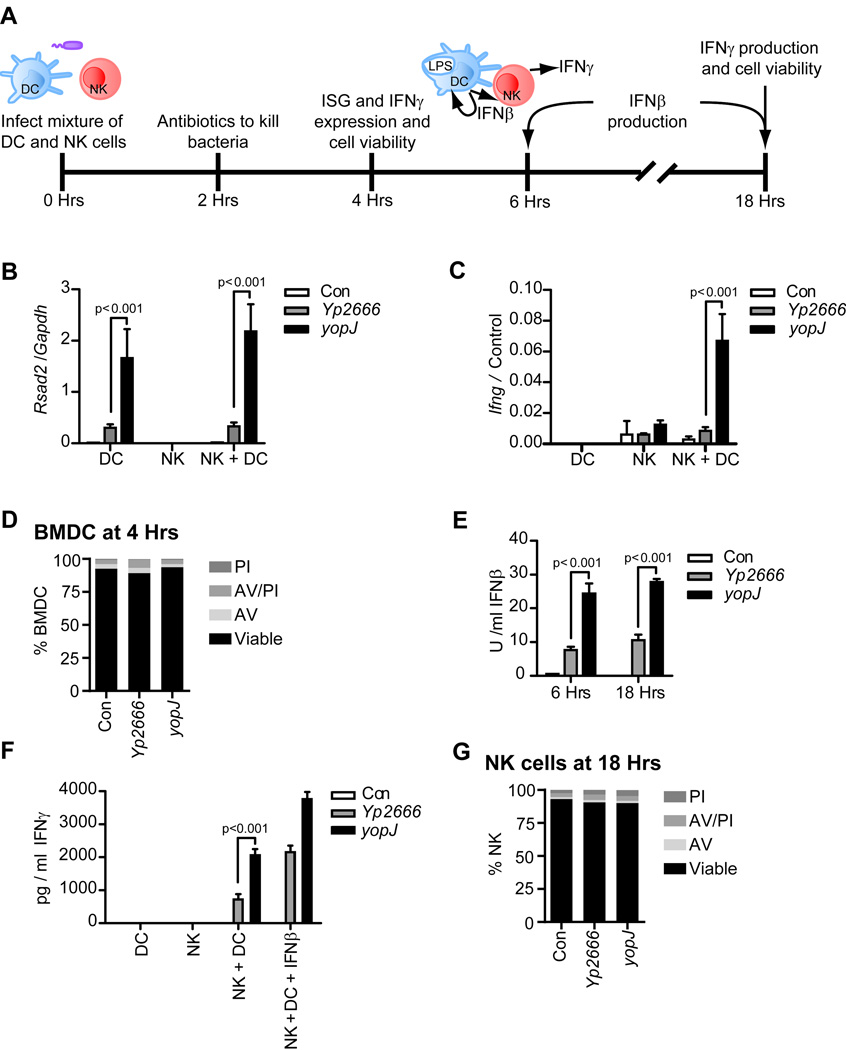

We considered the physiological significance of TRIF in DC biology. Upon encountering LPS, IFNβ production by DCs promotes NK cell activation and release of IFNγ, a cytokine with antibacterial activities (Zanoni et al., 2013)). To determine if YopJ inhibition of TRIF signaling prevents DC-mediated NK cell activation, a mixture of BMDCs and NK cells were infected with Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant. After 2 hr, antibiotics were added to kill bacteria (Fig. 6A). Gene expression, IFN production, and cell viability were assessed 4 and 18 hr later (Fig. 6A). At 4 hr post-infection, Rsad2 expression, an interferon stimulated gene (ISG) which can be used to monitor IFN activity, was suppressed in a YopJ-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). NK cells did not produce any IFN when infected with Yptb, as NK cells cultured alone with bacteria did not express Rsad2 or Ifng (Fig. 6B, C). However, the co-cultures of NK+BMDC induced Ifnγ expression in response to yopJ mutant infections (Fig. 6C). Notably, this response was blocked by Yp2666 (Fig. 6C). No YopJ-dependent cytotoxicity was observed throughout this experiment (Fig. 6D and S4A). In addition to blocking mRNA production, IFNβ and IFNγ secretion was suppressed in a YopJ-dependent manner, as assessed via bioassay and ELISA, respectively (Fig. 6E). Only NK+BMDC mixtures were capable of producing IFNγ, which illustrates the requirement of DCs for stimulating NK cells to produce IFNγ (Fig. 6F). Interestingly, addition of exogenous IFNβ restored the ability of Yp2666 infected NK+BMDC mixtures to produce IFNγ to levels similar to that elicited by yopJ mutant infection (Fig. 6F). This restoration of IFNγ by exogenous IFNβ indicates that the NK cells are not intrinsically incapable of producing IFNγ. NK cell viability was assessed in parallel with the IFNγ production at 18 hr, and no YopJ-dependent effects on AV/PI staining were observed (Fig. 6G and S4B).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of TRIF-dependent responses by Yptb disrupts DC-mediated NK cell activation. Experimental layout: NK cells and DCs were mixed in 0.7:1 ratio and infected with strains indicated at an MOI of 100 (A). At 2 hr post infection, cells were treated with antibiotics to kill bacteria (A). Gene expression, cytokine production, and cell viability were monitored at times indicated (A). 4 hr post infection, gene expression relative to cell specific house-keeping genes (Control: Gapdh for DCs or Ncr1 for NK cells) was monitored by qPCR (B and C) and DC cell viability was analyzed by flow cytometry with propidum iodide and annexin V staining (D). IFNβ production was assessed by bioassay at times indicated (E). At 18 hrs post infection, IFNγ production was assessed by ELISA (F). At time 0, exogenous IFNβ was added at 200 U/ml where indicated. Viability of NK cells, infected in parallel with co-cultures in (F), was analyzed by flow cytometry using propidum iodide and annexin V staining (G). Uninfected cells (Con) were used in all experiments. For gene expression analysis, bars represent the average and error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate readings from a one representative experiment of two. Statistics were calculated using ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. See also figure S4.

As an alternative approach, rather than co-infecting BMDCs and NK cells, we performed assays where NK cells were added to infected BMDCs after addition of antibiotics to kill the bacteria (Fig. S4C). Under these conditions, NK cells are never exposed to living bacteria, yet YopJ-dependent inhibition of Rsad2 expression, Ifnγ expression, and IFNγ production was still observed (Fig. S4D, E, and F). This result indicates that the inactivation of BMDCs by YopJ is sufficient to prevent NK cell activation. Furthermore, we verified that TRIF-dependent signaling is required for activation of NK cells by BMDCs, as TRIF-deficient BMDCs could not stimulate IFNγ production from NK cells during any infection (Fig. S4D, E, and F). Collectively, these data establish that at least one consequence of YopJ-mediated inhibition of TRIF signaling in BMDCs is to abrogate IFNγ production by NK cells.

Lastly, the relative roles of MyD88 and TRIF in a murine model of infection were examined. WT, TRIF-deficient, and MyD88-deficient mice were infected by gavage with either Yp2666 or the yopJ mutant and assessed for survival and bacterial burden in the spleens and livers. We did not observe a difference in survival between WT mice infected with either bacterial strain (Fig. S4G). However, compared to WT mice, Yp2666 infection appeared more lethal for mice deficient in MyD88 or TRIF, and those infected with Yp2666 fared worse than those infected with yopJ mutants (Fig. S4G, H, and I). To address this further, we analyzed the effect of mouse genotype on resistance to Yptb infection, and found MyD88-deficient mice were significantly reduced for their ability to survive infections compared to wild-type mice (Fig. S4H). TRIF-deficient mice exhibited a similar trend, although not significant from infections of wild-type mice (p=0.1597). One possible explanation for this difference between MyD88 and TRIF deficiencies is that MyD88 plays a broader role in host defense than simply mediating TLR4 signaling, as this adaptor is also important for IL-1R and TLR2-dependent activities crucial for controlling Yptb in vivo (Brodsky et al., 2010; Dessein et al., 2009; Philip et al., 2014; Weng et al., 2014)). Lastly, MyD88 mutants displayed higher bacterial burdens in the spleen and liver (Fig. S4J and K). However, bacterial burden was not influenced by the lack of YopJ (Fig. S4J and K). While additional work is necessary to clarify the relative roles of TRIF and MyD88 during Yersinia infections in vivo, these findings support the idea that both adaptor pathways activated by TLR4 play a role in host defense against these enteric pathogens.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that Yptb suppresses TRIF-dependent responses during infection of primary phagocytic cells, including DCs and macrophages. The strongest evidence supporting this conclusion comes from analysis of MyD88-deficient cells, where the only operable TLR4-dependent pathway is TRIF. TRIF signaling can therefore be included in the growing list of innate immune pathways that are targeted by virulent pathogens.

Our mechanistic analysis of the stages of TLR4 signaling revealed that YopJ does not interfere with any TLR4-dependent activities that specifically promote TRIF signaling, such as TLR4 endocytosis, TBK1 phosphorylation, or IRF3 activation. In addition, we observed no YopJ-dependent effects on myddosome formation or downstream NF-κB activation. Rather, the only proteins inactivated by YopJ in primary cells were MKKs and their downstream effectors. Direct evidence supporting this conclusion derives from our finding that YopJ inhibits the phosphorylation of MKKs, MAPKs, and c-Jun at times where IĸBα degradation, p65 phosphorylation, and p65 nuclear translocation were unabated. These data reveal that YopJ has a minimal ability to interfere with any pathway other than those activated by MKKs during infections, and indicate this effector is a highly specific Map Kinase Toxin, as suggested by Bliska and colleagues (Palmer et al., 1999)).

Despite this specificity for inactivating MKKs in vivo, YopJ is well-known to be a promiscuous enzyme in vitro, acetylating multiple kinases. The specificity of YopJ towards its substrates during infection is therefore not intrinsic, but must result from some feature(s) within the cytosol of infected cells. In this regard, we note that much of the previous work describing inhibition of the IKK pathway by YopJ was performed in immortal or non-immune cells (Schesser et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2004)) which may contain kinetically slow TLR4 pathways, as compared with primary phagocytes. Thus, in cell types that contain an inefficient TLR4 pathway, injected YopJ may have more time to acetylate substrates, and may therefore inactivate a broader spectrum of pathways. One prediction of this idea is that increasing the time that YopJ is present in the host cytosol should broaden the spectrum of substrates it can functionally inactivate. Indeed, acetylation studies are commonly performed by overexpression of YopJ, conditions where the timeline for substrate identification and pathway inhibition is on the order of hours to days (Mittal et al., 2006; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Paquette et al., 2012)). In contrast, our data indicate that during infections of phagocytes, YopJ has less than 30 minutes to acetylate enough substrates to block inflammatory gene expression. While this short time frame is not sufficient for YopJ to physiologically inactivate the IKK pathways, the MAPK pathway is strongly inhibited. Thus, we propose that kinases in the MAPK pathway are the first and preferred substrates of YopJ. Interestingly, a YopJ-like effector, VopA of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, does not block IKKs but only MAPKs (Trosky et al., 2004)). Collectively, we propose that YopJ-like proteins evolved to target the evolutionarily earliest innate immune pathways, the MAPKs. Indeed, YopJ belongs to a family of effector proteins that are also found in plant pathogens (Lewis et al., 2011)), suggesting that this is an evolutionarily ancient bacterial virulence strategy. Substrates within MAPK pathways may have been the first targets that YopJ evolved to inactivate, and remain the first targets during any infection. Secondary substrates (e.g. IKKs and TAK1) may only be targeted functionally at later points during infection, or not at all. YopJ may therefore be considered an unusual enzyme, whose substrate specificity is not hard-wired, but is determined by the speed of the signaling pathways in the infected cell.

The ability of YopJ to target MAPK pathways highlights a remarkably simple means by which bacteria can inactivate TLR4 signal transduction pathways. Rather than evolving multiple strategies to inactivate the MyD88 and TRIF pathways, YopJ has directed its actions towards the most common and ancient node in the TLR network, the MAPKs. The effectiveness of blocking TLR4-dependent transcription by targeting MAPKs may have bypassed the need for the evolution of additional effectors that inactivate TLR signal transduction. In this regard, pathogenic Yersinia can use a single effector protein to completely dismantle the transcription-inducing activity of the dominant innate immune receptor activated during infection, TLR4.

Despite the activities of YopJ to dismantle the TLR4 signaling network, and despite the ability of Yptb to disrupt DC-mediated NK cell activation, we did not observe a strong YopJ-dependent phenotype during infection of mice. We also did not observe a significant phenotype during infections of TRIF-deficient mice. This disconnect between striking mechanistic phenotypes and modest phenotypes during infections has been observed in several pathogenic bacterial effectors. Examples include effectors with elegant means of manipulating host physiology, such as substrates of the Legionella Type IV secretion system (Isaac and Isberg, 2014)) and effectors used by Salmonella spp. to invade mammalian cells (Zhou et al., 2001)). These virulence factors modulate specific host functions, yet deficiencies in individual Legionella or Salmonella effectors are not sufficient to prevent intracellular replication or invasion, respectively. An extreme example of this disconnect between in vitro and in vivo analyses comes from the bacterium used in this study, where even Yptb lacking their entire Type-III secretion system remain capable of establishing infections in certain tissues in vivo (Balada-Llasat and Mecsas, 2006)). Overall, our knowledge of the requirement for specific virulence activities during actual infections remains incomplete, and this study provides a mandate for future examination of this issue.

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture

C57BL/6J (Jax 000664), MyD88-deficient (Jax 009088), TRIF-deficient (Jax 005037), TLR4-deficient (C3H/HeJ, Jax 000659), and WT control for TLR4-deficient (C3H/HeSnJ, Jax 000661) were purchased from Jackson Labs. RIPK3-deficient and RIPK3/Caspase-8 double deficient mice were described (Philip et al., 2014)). BMDCs or BMDMs were differentiated from bone marrow in IMDM (Gibco), 10% GM-CSF, and 10% FBS, or DMEM (Gibco), 15% L929 supernatant, and 20% FBS, respectively. Immortal macrophages were cultured in DMEM complete media supplemented with 10% FBS. For experiments using inhibitors, BMDCs were pretreated with DMSO (vehicle control), zVADfmk (100 µM), specific inhibitors for ERK (PD98059, 50 nM), p38 (SB202190, 20 nM) or, JNK (SP600125, 50 nM) or a combination of these inhibitors for 2 hr prior to infections. Concentrations of DMSO were normalized across samples. For IĸBα degradation assays, BMDCs were treated with DMSO (vehicle) or cycloheximide (CHX) (50 µg/ml) at the time of infection. NK cells were isolated from red-blood cell lysed splenocytes using biotin conjugated anti-mouse CD49b antibody (Biolegend Cat# 108903, clone DX5) and magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACs) beads (Miltenyi Biotec). NK cell purity was 93% to 96%.

Bacterial strains and infections

Yptb strains IP2666 (Yp2666), IP2666 plasmid-deficient (plasmid-), IP2666 yopJ-deficient, and IP2666 yopJ-deficient complemented with yopJ or yopP were described (Brodsky and Medzhitov, 2008)). Yersinia strains 32777 (Yp32777) and 32777 yopJC172A mutant were gifts from Dr. James Bliska (SUNY, Stonybrook). To induce Type III secretion of Yop effectors, bacteria were cultured as described (Brodsky and Medzhitov, 2008)). Bacteria were added to cell cultures at the MOI indicated, and centrifuged at 300 × g for 3 min. Infected cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for times indicated in individual experiments.

Gene expression analysis, bioassay, and ELISA

RNA was isolated from mammalian cell cultures using Qiashedder (Qiagen) and GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (Life Technologies). Purified RNA was analyzed for gene expression on a CFX384 real time cycler (Bio-rad) using TaqMan RNA-to-CT 1-Step Kit (Applied Biosystems) with probes purchased from Life Technologies (See supplemental materials and methods). The Type I IFN bioassay was performed as described (Dixit et al., 2010)). ELISA for IFNγ was performed using Mouse IFN gamma ELISA Ready-SET-Go ELISA kit (eBioscience). Statistics were performed as indicated using Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Cell staining and flow cytometry

AV/PI staining was performed via the manufacturer’s protocol using the following Biolegend products: cell staining buffer, Annexin V binding buffer Propidium iodide, and anti-annexin V Alexa fluor 647 conjugate. Populations were gated based on cells individually stained with either propidium iodide or annexin V. TLR4 endocytosis assays were performed as described (Zanoni et al., 2011)). For all flow cytometry based experiments, data were acquired on a BD FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo v10 (FlowJo, LLC).

Western blotting, cell fractionation, and immunoprecipitation

Whole cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer and cleared by centrifugation at 17,000 × G for 5 min prior to boiling in SDS-loading buffer. For preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, cells were lysed in L1 buffer (50mM TRIS (pH-8.0), 2mM EDTA, 0.1% NP40, 10% glycerol, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Roche)) and lysates were centrifuged at 5000 RPM for 5 min at 4°C to pellet nuclei. Cytoplasm was isolated and boiled in SDS-loading buffer. Nuclei were washed once in L1 buffer, boiled in SDS-loading buffer, and homogenized by 4 passages through a 26 gauge needle. Protein for myddosome analysis was prepared as described (Bonham et al., 2014)). Immunoblotting was performed using standard molecular biology techniques (See supplemental materials and methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank James Bliska (SUNY Stony brook) for Yptb stains 32777 and 32777 yopJ-C172A, Jin Mo Park (Harvard) for p38α F/F-LysMCre marrow, and members of the Kagan lab for helpful discussions. JCK is supported by NIH grants AI093589, AI072955 and P30 DK34854, and an unrestricted gift from Mead Johnson & Company. Dr. Kagan holds an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. CVR is supported by NIH grant DK102317-01. ERG, MKP and JM were supported by NIH grants AI113141 and AI113166.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balada-Llasat J-M, Mecsas J. Yersinia has a tropism for B and T cell zones of lymph nodes that is independent of the type III secretion system. 2006 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxt LA, Garza-Mayers AC, Goldberg MB. Bacterial subversion of host innate immune pathways. Science. 2013;340:697–701. doi: 10.1126/science.1235771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham KS, Orzalli MH, Hayashi K, Wolf AI, Glanemann C, Weninger W, Iwasaki A, Knipe DM, Kagan JC. A promiscuous lipid-binding protein diversifies the subcellular sites of toll-like receptor signal transduction. Cell. 2014;156:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky IE, Medzhitov R. Reduced secretion of YopJ by Yersinia limits in vivo cell death but enhances bacterial virulence. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky IE, Palm NW, Sadanand S, Ryndak MB, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Bliska JB, Medzhitov R. A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Ruby T, Belhocine K, Bouley DM, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature. 2012;490:288–291. doi: 10.1038/nature11419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessein R, Gironella M, Vignal C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sokol H, Secher T, Lacas-Gervais S, Gratadoux J, Lafont F, Dagorn J. Toll-like receptor 2 is critical for induction of Reg3β expression and intestinal clearance of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Gut. 2009;58:771–776. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit E, Boulant S, Zhang Y, Lee AS, Odendall C, Shum B, Hacohen N, Chen ZJ, Whelan SP, Fransen M, et al. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez NC, Lozier A, Flament C, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Bellet D, Suter M, Perricaudet M, Tursz T, Maraskovsky E, Zitvogel L. Dendritic cells directly trigger NK cell functions: cross-talk relevant in innate anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:405–411. doi: 10.1038/7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003a;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, Rowe DC, Barnes BJ, Caffrey DR, Visintin A, Latz E, Monks B, Pitha PM, Golenbock DT. LPS-TLR4 signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-kappaB involves the toll adapters TRAM and TRIF. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003b;198:1043–1055. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Malireddi RK, Anand PK, Demon D, Vande Walle L, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. Toll or interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-beta (TRIF)-mediated caspase-11 protease production integrates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) protein- and Nlrp3 inflammasome-mediated host defense against enteropathogens. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:34474–34483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani T, Yamamoto M, Kumagai Y, Uematsu S, Kawase I, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Regulation of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes by MyD88 and Toll/IL-1 domain containing adaptor inducing IFN-β. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2005;328:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac DT, Isberg R. Master manipulators: an update on Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot translocated substrates and their host targets. Future microbiology. 2014;9:343–359. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan S, Young SK, Fessler MB, Liu Y, Malcolm KC, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Worthen GS. Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF)-mediated signaling contributes to innate immune responses in the lung during Escherichia coli pneumonia. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:3153–3160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan JC, Magupalli VG, Wu H. SMOCs: supramolecular organizing centres that control innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:821–826. doi: 10.1038/nri3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan JC, Su T, Horng T, Chow A, Akira S, Medzhitov R. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:361–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Sano Y, Todorova K, Carlson BA, Arpa L, Celada A, Lawrence T, Otsu K, Brissette JL, Arthur JSC. The kinase p38α serves cell type–specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro-and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1019–1027. doi: 10.1038/ni.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Lee A, Ma W, Zhou H, Guttman DS, Desveaux D. The YopJ superfamily in plant-associated bacteria. Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12:928–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Lo YC, Wu H. Helical assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature. 2010;465:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nature09121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal R, Peak-Chew SY, McMahon HT. Acetylation of MEK2 and I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:18574–18579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Mecsas J, Ghori N, Falkow S. Yersinia signals macrophages to undergo apoptosis and YopJ is necessary for this cell death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997;94:10385–10390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy SW, Khan N, McGrath S, Walkowicz MJ, Sharp F, Conlon JE, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Sweet C, Miyake K, et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ni1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motshwene PG, Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, Kao C, Ayaluru M, Sandercock AM, Robinson CV, Latz E, Gay NJ. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll-like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:25404–25411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Keitany G, Li Y, Wang Y, Ball HL, Goldsmith EJ, Orth K. Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science. 2006;312:1211–1214. doi: 10.1126/science.1126867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda K, Kitano H. A comprehensive map of the toll-like receptor signaling network. Molecular systems biology. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LE, Hobbie S, Galan JE, Bliska JB. YopJ of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is required for the inhibition of macrophage TNF-alpha production and downregulation of the MAP kinases p38 and JNK. Molecular microbiology. 1998;27:953–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LE, Pancetti AR, Greenberg S, Bliska JB. YopJ of Yersinia spp. is sufficient to cause downregulation of multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases in eukaryotic cells. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:708–716. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.708-716.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette N, Conlon J, Sweet C, Rus F, Wilson L, Pereira A, Rosadini CV, Goutagny N, Weber AN, Lane WS, et al. Serine/threonine acetylation of TGFbeta-activated kinase (TAK1) by Yersinia pestis YopJ inhibits innate immune signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12710–12715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008203109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip NH, Dillon CP, Snyder AG, Fitzgerald P, Wynosky-Dolfi MA, Zwack EE, Hu B, Fitzgerald L, Mauldin EA, Copenhaver AM. Caspase-8 mediates caspase-1 processing and innate immune defense in response to bacterial blockade of NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:7385–7390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403252111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power MR, Li B, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Lin T-J. A role of Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β in the host response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:3170–3176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VA, Vanaja SK, Waggoner L, Sokolovska A, Becker C, Stuart LM, Leong JM, Fitzgerald KA. TRIF licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 2012;150:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosadini CV, Kagan JC. Microbial strategies for antagonizing Toll-like-receptor signal transduction. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;32C:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schesser K, Spiik AK, Dukuzumuremyi JM, Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Wolf-Watz H. The yopJ locus is required for Yersinia-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and cytokine expression: YopJ contains a eukaryotic SH2-like domain that is essential for its repressive activity. Molecular microbiology. 1998;28:1067–1079. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotolongo J, Espana C, Echeverry A, Siefker D, Altman N, Zaias J, Santaolalla R, Ruiz J, Schesser K, Adkins B, et al. Host innate recognition of an intestinal bacterial pathogen induces TRIF-dependent protective immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2705–2716. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosky JE, Liverman AD, Orth K. Yersinia outer proteins: Yops. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:557–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosky JE, Mukherjee S, Burdette DL, Roberts M, McCarter L, Siegel RM, Orth K. Inhibition of MAPK signaling pathways by VopA from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:51953–51957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng D, Marty-Roix R, Ganesan S, Proulx MK, Vladimer GI, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Pouliot K, Chan FK-M, Kelliher MA. Caspase-8 and RIP kinases regulate bacteria-induced innate immune responses and cell death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014:201403477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403477111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Marek LR, Barresi S, Barbalat R, Barton GM, Granucci F, Kagan JC. CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4. Cell. 2011;147:868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni I, Spreafico R, Bodio C, Di Gioia M, Cigni C, Broggi A, Gorletta T, Caccia M, Chirico G, Sironi L. IL-15 cis presentation is required for optimal NK cell activation in lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammatory conditions. Cell reports. 2013;4:1235–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ting AT, Marcu KB, Bliska JB. Inhibition of MAPK and NF-kappa B pathways is necessary for rapid apoptosis in macrophages infected with Yersinia. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:7939–7949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Chen LM, Hernandez L, Shears SB, Galan JE. A Salmonella inositol polyphosphatase acts in conjunction with other bacterial effectors to promote host cell actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and bacterial internalization. Molecular microbiology. 2001;39:248–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Monack DM, Kayagaki N, Wertz I, Yin J, Wolf B, Dixit VM. Yersinia virulence factor YopJ acts as a deubiquitinase to inhibit NF-kappa B activation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:1327–1332. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Tan A, Hershenson MB. Yersinia YopJ inhibits pro-inflammatory molecule expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2004;140:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.