Abstract

Darocha, Tomasz, Sylweriusz Kosinski, Maciej Moskwa, Anna Jarosz, Dorota Sobczyk, Robert Galazkowski, Marcin Slowik, and Rafal Drwila. The role of hypothermia coordinator: A case of hypothermic cardiac arrest treated with ECMO. High Alt Biol Med 16:352-355, 2015.—We present a description of emergency medical rescue procedures in a patient suffering from severe hypothermia who was found in the Babia Gora mountain range (Poland). After diagnosing the symptoms of II/III stage hypothermia according to the Swiss Staging System, the Mountain Rescue Service notified the coordinator from the Severe Accidental Hypothermia Center (CLHG) Coordinator in Krakow and then kept in constant touch with him. In accordance with the protocol for managing such situations, the coordinator started the procedure for patients in severe hypothermia with the option of extracorporeal warming and secured access to a device for continuous mechanical chest compression. After reaching the hospital, extracorporeal warming with ECMO support in the arteriovenuous configuration was started. The total duration of circulatory arrest was 150 minutes. The rescue procedures were supervised by the coordinator, who was on 24-hour duty and was reached by means of an alarm phone. The task of the coordinator is to consult the management of hypothermia cases, use his knowledge and experience to help in the diagnosis and treatment. and if the need arises refer the patient for ECMO at CLHG. Good coordination, planning, predicting possible problems, and acting in accordance with the agreed procedures in the scheme, make it possible to shorten the time of reaching the destination hospital and implement effective treatment.

Key Words: : cardiopulmonary resuscitation, hypothermia, mountaineering, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, rewarming

Introduction

Severe accidental hypothermia is a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the years 2009–2012 the Polish National Statistics Department reported 1836 deaths due to excessive exposure to natural cold. The Severe Accidental Hypothermia Center (CLHG—Centrum Leczenia Hipotermii Glebokiej) was set up in Krakow in 2013 (Darocha, 2015). It is a unit functioning within the structure of the Cardiac Surgery Clinic, established in order to improve the effectiveness of the treatment of patients in the advanced stages of severe hypothermia. The coordination of rescue operations (over an area of 32,950 square km) was entrusted to a group of doctors (4 coordinators), who support the decision-making and organization of the operational process from the time of obtaining the information about the incident until reaching CLHG.

Case Report

On December 29, 2014 at 19:15, the rescuer on duty at the Mountain Rescue Service (GOPR) received information about a group of tourists who had lost their way in the top regions of Babia Gora Mount, at the height of about 1620 meters above sea level. Air temperature was between −6° and −8°C (windchill factor below −0°C), the wind was W-WNW with gusts up to over a few dozen km per hour, and the falling snow significantly reduced visibility. The Mountain Rescue Service search party on duty (two people) left immediately to conduct the search. Later they were joined by others, so that 19 Mountain Rescue Service members eventually took part in the operation.

At 19:30, in accordance with the protocol, the member of the Mountain Rescue notified the Severe Accidental Hypothermia Center (CLHG) about the search operation. At 20:55 the victims were found. Two men were conscious and in stage I of hypothermia, while the third one, sitting in the snow, was confused, agitated, and aggressive towards the rescuers who suspected the II/III stage of hypothermia according to the Swiss Staging System. Information about this situation was passed on by phone to the CLHG coordinator by the GOPR rescuers.

The victims were covered with metalized foil, put in thermal sleeping bags and in Akia emergency rescue sleds. External warming by means of heating pads was started, and continuous heart rate monitoring using an AED was implemented. At 22:08 the Mountain Rescue Service (GOPR) rescuers started the difficult transport of the victims downhill, in the direction of the meeting place agreed upon with the teams of emergency medical services who were to take further care of the victims.

On the basis of the information received by phone, the CLHG coordinator started the procedure that is in place for patients in severe hypothermia, with the option of extracorporeal warming. He notified the team on duty at the Cardiac Surgery Clinic of the John Paul II Hospital in Krakow, and an operating theater, as well as ECMO equipment were booked.

Due to poor atmospheric conditions (bad weather), it was not possible to use an emergency helicopter. The CLHG Coordinator and the Dispatch Center in Krakow arranged ambulance transport with a doctor for the patient suspected to have II/III stage hypothermia. Transport was to take place from the scene of the incident directly to the John Paul II Hospital. The decision was made to supply the ambulance with extra equipment (i.e., a device for mechanical chest compression and a low-temperature thermometer, both of which were taken from another emergency service ambulance working in the vicinity). After receiving the personal details of the victim suspected of II/III stage HT, the coordinator for extracorporeal treatment of severe hypothermia patients took the medical history of the victim from his family. Information about the lack of allergies and chronic illnesses and the medication taken was obtained.

At 23:05 the rescuers reached the place where the emergency medical rescue team were waiting. After being carried into the warmed ambulance and having the monitoring devices connected, at 23:11 the patient suspected of hypothermia (HT) III was diagnosed with ventricular fibrillation (VF). The team managed to measure his infrared tympanic temperature. It was 22°C. First manual and then mechanical chest compression was started. The patient was intubated, intravenous access was obtained and the transfusion of warm infusion fluids was implemented.

Defibrillation was attempted three times, but unsuccessfully. The CLHG coordinator advised the team managing the transport not to undertake advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) procedures there and told them to start transporting the patient to hospital as quickly as possible. At 23:26 the team set off with the JPII Hospital as their destination. Mechanical chest compression was continued all the time.

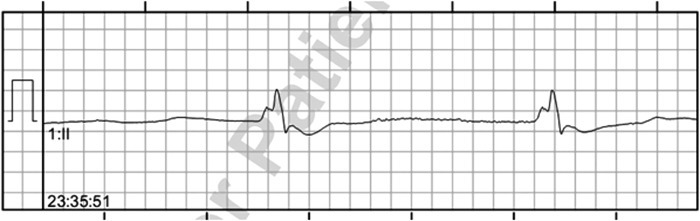

Thanks to the continuous cooperation with the medical rescue team, the coordinator was able to evaluate the course of the ACLS procedures undertaken during transport. At 23:35 there was a brief period of agonal cardiac rhythm with PEA (pulseless electrical activity) (Fig. 1). Other than that, VF persisted throughout transport. The team covered 98 km by land. Throughout the journey, the CLGH coordinator had current information about the location of the emergency medical rescue team and the expected time of arrival at the destination hospital.

FIG. 1.

ECG showing the agonal heart rhythm.

On arrival at the CLHG, the patient had asystole and anisocoria (the left pupil was larger than the right one). With the emergency rescue team, and in urgent mode, he was taken to the already prepared operating theater, where he arrived at 1:15. After cannulation of the femoral artery and femoral vein, arteriovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was started at 1:35.

The arterial blood gas values are presented in Table 1. The blood glucose showed hypoglycemia. Core temperature measured by esophageal probe was 22°C. Ventricular fibrillation occurred when his core body temperature was 27°C. 200 J defibrillation was attempted, achieving the return of spontaneous circulation, but due to the persisting symptoms of cardiogenic shock, ECMO was continued until the morning hours of 1:01:2015 (duration of ECMO therapy—32 hours). Normothermia was achieved after 7.5 hours of extracorporeal therapy. The duration of circulatory arrest, from the time of diagnosis to administering extracorporeal circulation was 150 minutes.

Table 1.

Arterial Blood Gas Values, Blood Glucose, Hemoglobin and Blood Chemistry Levels

| On arrival, at 01:30 am | Normothermia at 09:00 am | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.91 | 7.52 |

| pCO2 [mmHg] | 75.8 | 27.1 |

| PO2 [mmHg] | 49.4 | 153 |

| BE [mmol/L] | −20.8 | −0.1 |

| K [mmol/L] | 4.6 | 3 |

| Na [mmol/L] | 141 | 146 |

| Lac [mmol/L] | 13.5 | 2.3 |

| HCO3 [mmol/L] | 14.4 | 21.8 |

| Glucose [mmol/L] | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Hb [g/dL] | 14.5 | 10.2 |

The patient regained consciousness and was extubated on January 2, 2015, and left the ICU on January 7, 2015 in a good neurological status (Glasgow Coma Scale 15, Cerebral Performance Category 1), without anisocoria. At the time of leaving the hospital, the echocardiogram showed that the patient had a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (EF-65%). After 6 months, neurological examination did not show any functional impairment.

Discussion

Prognosis in circulatory arrest in the course of accidental hypothermia is surprisingly good, despite even long periods of hypoperfusion (Dunne, 2014). Such treatment results are possible mainly owing to the “cold” protection of the brain, maintaining continuous organ perfusion obtained by means of manual or mechanical chest compression, and using extracorporeal warming (Brown et al., 2012; Dunne et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2014; Paal and Brown, 2014; Zafren et al., 2014). The guidelines proposed by Gordon et al. (2015) suggest to start immediate continuous cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), to minimize interruptions and apply mechanical chest compressions as soon as possible, in circulatory arrest due to primary severe hypothermia.

Delayed or intermittent CPR may be considered only when continuous CPR is impossible, particularly during difficult evacuations. In the described case, the decision was made to supply the ambulance with extra equipment (i.e., a device for mechanical chest compression and a low-temperature thermometer, both of which were taken from another emergency service ambulance working in the vicinity).

Mechanical compression does not have a survival advantage over manual compression, but manual compression cannot be done safely or effectively in a moving ambulance. Using mechanical chest compression system (LUCAS 2) allowed minimized interruptions in CPR. The fourth element, which can significantly impact the prognosis is the appropriate organization of the rescue operation. Good coordination, planning, foresight, and acting in accordance with the agreed procedures in the rescue scheme, makes it possible to shorten the time of reaching the destination hospital and effective treatment (Gordon et al., 2014).

The case described here is an example of optimal management on the part of the Coordinator and provides proof that the system that had been elaborated works in an effective way. Notifying the coordinator of a search operation is one of the more important elements of the procedures in the rescue scheme under discussion. According to the algorithm that is in place, mountain rescue services (6 units of mountain rescue services covering the area of 17 680 km2) are obliged to give notification of rescue operations, especially ones conducted in conditions when there is a risk of the occurrence of hypothermia.

Thanks to this, it is possible to start preparations early. What is equally significant is the regular exchange of information between the Coordinator and the units conducting the search and rescue medical operations. In the case described here, the Coordinator had complete information about the victim transmitted to him by mountain rescuers, and was given all the parameters of the ACLS procedures undertaken during the ambulance transport.

The immediate provision of the device for mechanical chest compression, which was taken aboard the ambulance transporting the patients as extra equipment, proved how excellent the planning and foresight of the operation was. This is because the good quality of compression is a significant factor impacting prognosis. On the basis of the information gathered, we have created a regularly updated map of the equipment at the disposal of hospitals and medical emergency services, so that Coordinators can use them as required.

Cooperation with the Dispatch Center in Krakow, which has agreed to the procedures in the rescue scheme elaborated by the CLHG, is a very important aspect of such operations. In the case described here, on the basis of the information obtained, the Coordinator made the decision that there was a high likelihood of circulatory arrest occurring, and therefore made arrangements for the device to be waiting for the patient at the place where he was taken over from the mountain rescuers.

Accidental hypothermia, and particularly its advanced stages, is infrequent. General knowledge about the procedures and treatment in managing such cases can therefore be incomplete and out of date. We confirmed that in our recent survey among 42 ERs in Poland providing emergency healthcare for the population of 5,305,000 (Kosinski et al., 2015). The knowledge of the Coordinator and his consultation can therefore be of great significance.

We believe that in the case being described, this element (role of Coordinator) could also have influenced the outcome. It is, however, worth noticing that thanks to continuous information campaigns and regular training, the procedures in the rescue scheme that were developed are more and more universally recognized and used. Knowledge of the principles of proceeding in hypothermia must be generally known, especially in the mountain rescue community. The recommendations and guidelines elaborated by ICAR and ERC are therefore invaluable because they provide the basis for developing local protocols (Soar et al., 2010; Durrer et al., 2013).

The case described here confirms that it is possible to achieve full recovery of neurological functions in patients with circulatory arrest in the course of severe hypothermia, even after resuscitation procedures taking a few hours. At the same time, we have proven the effectiveness of the system that had been elaborated, thanks to which patients are referred to specialized hypothermia centers by means of a precisely pre-arranged route and set procedures. For obvious reasons, it is not possible to develop an ideal system, one in which all the possibilities can be foreseen.

In another mountain rescue operation supervised by a CLHG Coordinator, some delays were unavoidable, and resuscitation procedures before introducing ECMO support in the destination hospital took 5 hours and 45 minutes (own, unpublished data). However, similarly to the case fully described in that article, a full recovery of neurological functions was achieved.

The element that could have been improved in this case was the delayed measurement of core temperature. Neither the mountain rescuers, nor the emergency medical rescue team had appropriate equipment to perform this. Core temperature (Tc) measurement is the only diagnostic tool to assess the severity of hypothermia accurately. Early Tc measurement can significantly influence the course of rescue and medical proceedings and is by all means recommended (Strapazzon et al., 2014). For in-filed Tc measurements, the optimal thermometer should be minimally invasive, easy to handle, and independent of environmental conditions. Epitympanic temperatures were comparable to invasive Tc measurements in cases of deep hypothermia, however there is no clear evidence for the reliability of epitympanic Tc at low ambient temperatures.

Every new case of hypothermia provides a topic for discussion to us and an incentive to introduce modifications raising the effectiveness of the system that had been introduced. Its basic elements will always be the knowledge of the team comprising the rescue units, the cooperation of the units taking part in the operation, and good coordination of activities.

Conclusion

Good coordination, planning, predicting possible problems, and acting in accordance with the agreed procedures in the scheme, make it possible to shorten the time of reaching the destination hospital and implement effective treatment. The Severe Accidental Hypothermia Center was set up in Krakow in 2013 in order to improve the effectiveness of the treatment of patients in the advanced stages of severe hypothermia.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicting financial interests.

References

- Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, and Paal P. (2012). Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med 367:1930–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darocha T, Kosiński S, Jarosz A, Gałązkowski R, Sadowski J, and Drwiła R. (2015). Severe accidental hypothermia center. Eur J Emerg Med 22:288–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne B, Christou E, Duff O, and Merry C. (2014). Extracorporeal-assisted rewarming in the management of accidental deep hypothermic cardiac arrest: A systematic review of the literature. Heart Lung Circ. 23:1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrer B, Brugger H, and Syme D; International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine. (2003). The medical on-site treatment of hypothermia ICAR-MEDCOM recommendation. High Alt Med Biol 4:99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon L, Ellerton JA, Paal P, Peek GJ, and Barker J. (2014). Severe accidental hypothermia. BMJ 348:g1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski S, Darocha T, Galazkowski R, Drwila R. (2015). Accidental hypothermia in Poland. Estimation of prevalence, diagnopstic methods and treatment. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerge Med. 23:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, Pelurson N, Khabiri E, Siegenthaler N, and Walpoth BH. (2014). Sequela-free long-term survival of a 65-year-old woman after 8 hours and 40 minutes of cardiac arrest from deep accidental hypothermia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147:e1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paal P, and Brown D. (2014). Cardiac arrest from accidental hypothermia, a rare condition with potentially excellent neurological outcome, if you treat it right. Resuscitation 85:707–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon L, Paal P, Ellerton JA, Brugger H, Peek GJ, and Zafren K. (2015). Delayed and intermittent CPR for severe accidental hypothermia. Resuscitation 90:46–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soar J, Perkins GD, Abbas G, Alfonzo A, Barelli A, Bierens JJ, Brugger H, Deakin CD, Dunning J, Georgiou M, Handley AJ, Lockey DJ, Paal P, Sandroni C, Thies KC, Zideman DA, and Nolan JP. (2010). European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation 81:1400–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strapazzon G, Procter E, Paal P, and Brugger H. (2014). Pre-hospital core temperature measurement in accidental and therapeutic hypothermia. High Alt Med Biol 15:104–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafren K, Giesbrecht GG, Danzl DF, Brugger H, Sagalyn EB, Walpoth B, Weiss EA, Auerbach PS, McIntosh SE, Némethy M, McDevitt M, Dow J, Schoene RB, Rodway GW, Hackett PH, Bennett BL, and Grissom CK. (2014). Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for the out-of-hospital evaluation and treatment of accidental hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med 25:425–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]