Abstract

Hyperlipidemia and inflammation contribute to the development of atherosclerotic lesions. Our objective was to determine antiatherogenic effect of edible blue-green algae (BGA) species, that is, Nostoc commune var. sphaeroides Kützing (NO) and Spirulina platensis (SP), in apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE−/−) mice, a well-established mouse model of atherosclerosis. Male ApoE−/− mice were fed a high-fat/high-cholesterol (HF/HC, 15% fat and 0.2% cholesterol by wt) control diet or a HF/HC diet supplemented with 5% (w/w) of NO or SP powder for 12 weeks. Plasma total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) were measured, and livers were analyzed for histology and gene expression. Morphometric analysis for lesions and immunohistochemical analysis for CD68 were conducted in the aorta and the aortic root. NO supplementation significantly decreased plasma TC and TG, and liver TC, compared to control and SP groups. In the livers of NO-fed mice, less lipid droplets were present with a concomitant decrease in fatty acid synthase protein levels than the other groups. There was a significant increase in hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor protein levels in SP-supplemented mice than in control and NO groups. Quantification of aortic lesions by en face analysis demonstrated that both NO and SP decreased aortic lesion development to a similar degree compared with control. While lesions in the aortic root were not significantly different between groups, the CD68-stained area in the aortic root was significantly lowered in BGA-fed mice than controls. In conclusion, both NO and SP supplementation decreased the development of atherosclerotic lesions, suggesting that they may be used as a natural product for atheroprotection.

Key Words: : atherosclerosis, blue-green algae, Nostoc commune var. sphaeroids kutzing

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It affects 16.3 million in the United States, according to a report by the American Heart Association in 2012.1 CHD is positively related with elevated plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels.2,3 Atherosclerosis is initiated when excessive LDL particles in the circulation enter the arterial intima and become oxidized.4,5 The oxidized LDL in the intima stimulates the endothelial cells to produce a series of cell adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, to facilitate the recruitment of circulating monocytes, which facilitate atherosclerotic lesion formation.5,6 As such, both lipid and inflammatory components play a critical role in atherogenesis, and therefore, therapeutic drugs, such as statins, niacin, fibrates, and thiazolidinediones, which exert lipid-lowering and/or anti-inflammatory effects, have been clinically used for the prevention of atherosclerosis.5,7 Although drugs are effective, they are commonly associated with adverse side effects,8 and the interest in using natural products for CHD prevention has been growing.

Blue-green algae (BGA) are one of the most primitive forms of photosynthetic prokaryotes found in aquatic ecosystems. Spirulina platensis (SP) and Nostoc commune (NO) have a long history of human consumption, and they are rich in essential amino acids, fibers, B vitamins, minerals, and pigments, such as β-carotene, xanthophyll, chlorophyll, and phycocyanin.9–13 Studies have suggested that BGA have antiviral, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antiallergic, antidiabetic, antibacterial, and lipid-lowering functions.14 Antiatherosclerotic effects of SP have also been suggested in New Zealand white rabbits fed a high-cholesterol diet containing 1% or 5% SP (w/w).15

We previously reported that NO exerts a hypocholesterolemic effect in mice,16 and NO and SP extracts inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced production of proinflammatory mediators in RAW 264.7 macrophages by the inactivation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway.17,18 Furthermore, we also found that splenocytes isolated from apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE−/−) mice, which were fed NO or SP, secreted less interleukin 6 (IL-6) compared with those from control mice.18 Given that dyslipidemia and inflammation facilitate atherosclerotic lesion development, the objective of this study was to determine antiatherogenic effects of NO and SP in ApoE−/− mice, a well-established mouse model of atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and diets

Thirty-six male ApoE−/− mice at the age of 8 weeks were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and housed in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. After a week of acclimation, mice were randomly assigned into three groups: an atherogenic high-fat/high-cholesterol (HF/HC) control diet (15% of fat and 0.2% of cholesterol by wt), a HF/HC supplemented with 5% NO (w/w), or a HF/HC diet supplemented with 5% SP (w/w) (Control n = 10, NO n = 12, SP n = 14). NO (AlgaBerry™) and SP powder (Earthrise® Natural Spirulina) were kindly provided by the Algaen Corporation (Winston-Salem, NC, USA) and Earthrise Nutritionals (Irvine, CA, USA), respectively. A detailed diet composition is shown in Table 1. Mice were given free access to diet and water throughout the study. Body weights and diet consumption were recorded weekly. At the end of 12th week on the experimental diets, mice were anesthetized by ketamine HCl/xylazine (120/6 mpk) (Henry Schein, Melville, NY, USA) and blood was collected into a 3.5-mg EDTA-containing tube (BD Vacutainer, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) by cardiac puncture. Subsequently, the rib cages were opened and hearts were perfused with cold 1× PBS at a flow rate of 4 mL/min for 3 min. Liver samples were immersed in 10% formalin or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Aorta samples were collected and fixed in 10% formalin for en face analysis. To preserve heart samples for aortic root lesion analysis, two thirds of each heart was perpendicularly cut from the aortic root and put into a tissue mold with the ventricle side facing down, after which the heart was covered with Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature (OCT) liquid (Torrance, CA, USA) and frozen in dry ice. The frozen tissue blocks were kept in −80°C until use. All animal experimental procedures were conducted with the approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Connecticut.

Table 1.

High-Fat High-Cholesterol Atherogenic Diet Supplemented with 5% Blue-Green Algae (w/w)

| g/Kg diet | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient | Control | 5% NO | 5% SP |

| Cornstarch | 353.69 | 338.69 | 338.69 |

| Casein | 155.00 | 155.00 | 155.00 |

| Sucrose | 140.00 | 112.40 | 112.40 |

| Dextrinized cornstarch | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Coconut oil | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Soybean oil | 50.00 | 46.85 | 46.85 |

| Fibera | 40.00 | 35.75 | 35.75 |

| Guar gum | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Cholesterol | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Mineral mixb | 35.00 | 35.00 | 35.00 |

| Vitamin mixc | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| L-Cystine | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| t-Butylhydroquinone | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Dried Algae Powder | 0.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

Solka-Floc cellulose; bAIN-93 mineral mix; cAIN-93 vitamin mix.

NO, Nostoc commune var. sphaeroides Kützing; SP, Spirulina platensis.

Plasma alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and lipid analysis

Blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min at 4°C to collect plasma. Plasma samples were analyzed for aspartate aminotransferase (ALT) and alanine aminotransferase (AST) levels using a Cholestech LDX ALT/AST Test Cassette and a Cholestech LDX System (Cholestech Corporation, Hayward, CA, USA). Plasma triglyceride (TG) was quantified using an L-Type Triglyceride M Kit from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA, USA) and plasma total cholesterol (TC) was measured using a Cholesterol Reagent Set from Pointe Scientific (Canton, MI, USA), as previously described.19

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for plasma tumor necrosis factor α levels

Plasma tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) levels were measured using an ELISA Kit from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and optimal densities were read at 450 nm using a BioTek microplate reader (Winooski, VT, USA).

Hepatic lipid measurement

Lipids from ∼0.2 g of liver samples were extracted into chloroform:methanol (2:1) and solubilized in Triton X-100, as previously described.17 Liver TC and TC were measured as described above.

Intestinal cholesterol absorption

Fractional intestinal cholesterol absorption was measured using a dual-isotope method, as previously described.16

Histological analysis of mouse livers

Liver samples fixed in 10% formalin were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin at the Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (Storrs, CT, USA). The sections were visualized at 10× magnification using an AxioCam MRc (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany).

Morphometric analysis of aortic lesions

After removing adipose and connective tissues, aorta samples fixed in 10% formalin were longitudinally cut open and pinned down. Aortas were then rinsed with sterile water and covered with 70% ethanol for 5 min, after which they were stained using 0.5% Oil red O (ORO) in isopropanol for 20 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the aorta samples were washed with 70% ethanol and images were captured with a Samsung NX1000 camera with a 1:2.8 60 mm micro ED OIS lens. Aortic lesions were quantified using the NIH ImageJ software, and data were expressed as a percentage of lesion area per total aorta area.

To quantify atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root, OCT frozen heart samples were sliced to a thickness of 8 μm using a Leica CM3050 cryostat (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) starting from the bottom of the aortic valve leaflets. A total of eight sections of each mouse tissue sample were collected on a Superfrost plus microscope slide (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The slides were then thawed at room temperature and fixed in cold 10% formalin for 15 min, after which they were air-dried for 20 min and quickly rinsed with 40% isopropanol. Subsequently, the tissue sections were immersed in an ORO working solution (two parts of water and three parts of 0.5% ORO in isopropanol) for 20 min and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 45 sec. To yield a blue-purple color of tissues, the slides were dipped in 0.1% sodium bicarbonate in water for 5 sec, after which they were rinsed thoroughly with water, air-dried, and mounted with glycerin jelly (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). The slides were viewed at 5× magnification using an AxioCam MRc (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), and the total lesion area was quantified using the NIH ImageJ software.

Immunohistochemistry for CD68 in the aortic root

The aortic root sections described above were fixed in cold 10% formalin for 10 min, rinsed with 1× DPBS, and air-dried. A circle was drawn around a tissue using an ImmEdge immunohistochemistry barrier pen (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Samples were blocked with 25 μL of blocking solution containing 100 μg/mL of Fab anti-mouse (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1× DPBS for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, tissues were incubated with an anti-CD68 primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) for 1 h and washed thrice with 1× DPBS. The tissues were then incubated with an anti-mouse-IgG-rhodamine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) antibody in 1% BSA in 1× DPBS. Fluorescence signals were detected using an AxioCam MRc at 5× magnification. The total area with fluorescence signals was measured and quantified with the NIH ImageJ software.

Gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR

Tissue samples (∼200 mg) were homogenized in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) for RNA isolation according to the manufacturer's protocol, as previously described.18,20 The quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis for hepatic gene expression was conducted using a SYBR Green quantitation procedure and CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primer sequences were designed according to GenBank database using the Beacon Designer software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and primer sequences will be available upon request.

Western blot analysis

Tissue lysates were prepared, and Western blot analysis was performed, as previously described.17,21 The following antibodies were used: 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) (Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA, USA); LDL receptor (LDLR) (Abcam); and sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP-2) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The monoclonal antibody against β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect β-actin as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Newman–Keuls pairwise comparison, or unpaired t-test, were performed to compare mean differences between the groups using the GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). An α-level of P < .05 was considered statistically significant, and all data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

General observations and plasma chemistry

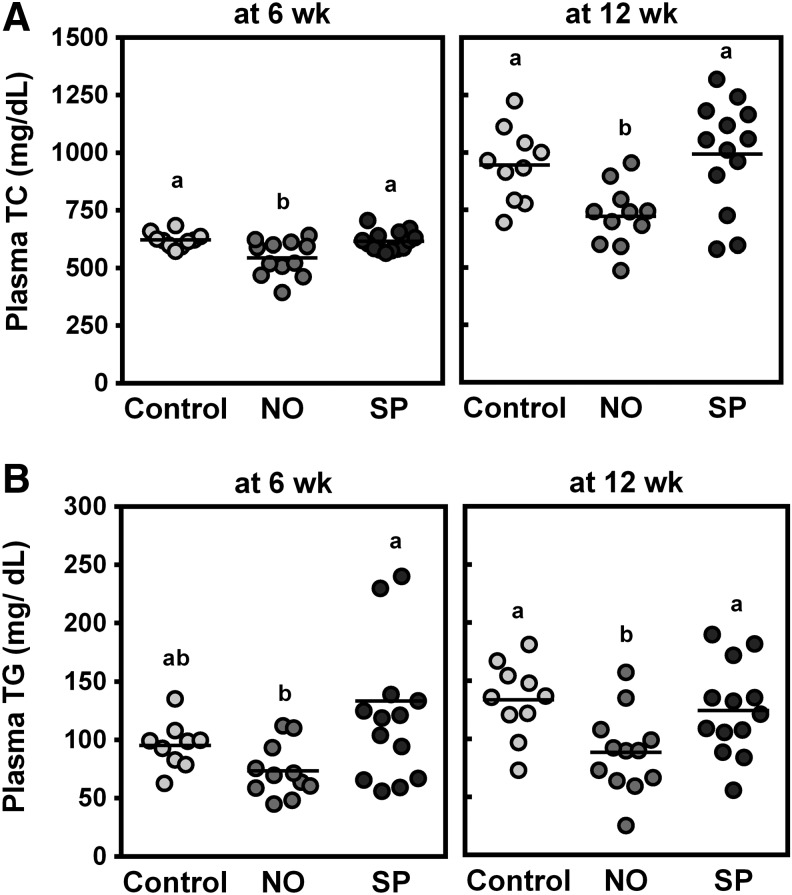

There were no significant differences in body weight gain after 12 weeks on the experimental diets or daily food consumption between the groups (Table 2). Plasma concentrations of TNFα or AST and ALT were not significantly altered by BGA supplementation compared with control animals. NO supplementation significantly decreased plasma TC at 6 and 12 weeks, while SP did not alter the levels compared with controls (Fig. 1A). Plasma TG levels were also lowered by NO, but not SP, at 12 weeks (Fig. 1B).

Table 2.

Body Weight, Diet Consumption, Liver Weight, and Intestinal Cholesterol Absorption in Male ApoE−/− Mice Fed a High-Fat High-Cholesterol Diet Supplemented with 5% NO or SP (w/w)

| Initial body weightg | Body weight gaing | Food consumptiong/day/mouse | Plasma TNFαpg/mL | Plasma ASTU/L | Plasma ALTU/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 22.8 ± 0.8 | 9.24 ± 0.76 | 4.02 ± 0.10 | 4.43 ± 0.13 | 35.9 ± 6.2 | 78.5 ± 6.7 |

| NO | 22.4 ± 0.4 | 7.89 ± 0.59 | 4.27 ± 0.16 | 4.56 ± 0.78 | 32.1 ± 3.4 | 77.9 ± 15.6 |

| SP | 22.2 ± 0.5 | 9.15 ± 0.97 | 4.15 ± 0.11 | 4.15 ± 0.42 | 33.6 ± 3.8 | 79.4 ± 6.8 |

Values represent mean ± SEM (Control n = 10, NO n = 12, SP n = 14).

FIG. 1.

Effects of blue-green algae (BGA) supplementation on plasma total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) concentrations at 6 and 12 weeks. Male ApoE−/− mice were fed an atherogenic diet or atherogenic diet supplemented with 5% NO or 5% SP for 12 weeks. Plasma TC (A) and TG (B) levels were determined by an enzymatic analysis after 6 (left panel) or 12 (right panel) weeks on experimental diets. Horizontal lines are means, and groups with a different letter are significantly different (P < .05). Values are mean ± SEM. n = 10 for control, n = 12 for NO, and n = 14 for SP.

Effects of BGA supplementation on liver lipid

Mice fed a HF/HC diet supplemented with NO showed a significantly lower liver weight than control and SP groups (Fig. 2A). Liver TC levels were also lower in NO group than controls (Fig. 2B). Although we did not observe significant differences in liver TG levels between the groups (Fig. 2C), there was noticeably less lipid accumulation in the livers of NO-fed mice compared with the other groups, as measured by histological analysis (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Effects of BGA supplementation on hepatic lipid metabolism of ApoE−/− mice fed an atherogenic diet or atherogenic diet supplemented with 5% NO or 5% SP for 12 weeks. (A) liver weight. (B) liver TC content. (C) liver TG levels. Horizontal lines are means, and groups with a different letter are significantly different (P < .05).Values are mean ± SEM. n = 12 for NO and n = 14 for SP. (D) Representative liver sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. 40× magnification. Bar = 20 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jmf

mRNA and protein expression of genes related to lipid metabolism in the liver

The expression of genes related to lipid metabolism was measured in the liver to gain mechanistic insight. There were no significant differences in the mRNA levels of genes for cholesterol synthesis and LDL uptake, that is, HMGR and LDLR, respectively, between groups (Table 3). mRNA abundance of lipogenic genes, including fatty acid synthase (FAS) and stearoyl CoA desaturase 1 (SCD-1), as well as genes, those for fatty acid oxidation, such as carnithin palmitoyl transferase 1α (CPT-1α) and acylCoA oxidase 1 (ACOX-1), were not significantly altered by either BGA supplementation. However, SP-fed mice showed significantly higher LDLR protein levels in the liver, while NO supplementation significantly decreased FAS protein compared with the other groups.

Table 3.

The Expression of Lipogenic Genes in the Livers of ApoE−/−Mice Fed a High-Fat High-Cholesterol Diet Supplemented with 5% NO or SP (w/w)

| Gene | Control | NO | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA1 | HMGR | 0.73 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 0.84 ± 0.05 |

| LDLR | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 1.10 ± 0.15 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | |

| FAS | 1.10 ± 0.12 | 1.09 ± 0.17 | 0.93 ± 0.10 | |

| SCD-1 | 1.45 ± 0.18 | 1.23 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.11 | |

| CPT-1α | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 1.14 ± 0.17 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | |

| ACOX-1 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 1.12 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | |

| Protein1 | Mature SREBP-2 | 1.45 ± 0.18 | 1.23 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.11 |

| HMGR | 1.39 ± 0.20 | 1.09 ± 0.16 | 1.30 ± 0.16 | |

| LDLR | 0.87 ± 0.06b | 1.02 ± 0.11b | 1.54 ± 0.10a | |

| FAS | 1.44 ± 0.12a | 1.15 ± 0.09b | 1.68 ± 0.11a |

Values represent mean ± SEM (Control n = 10, NO n = 12, SP n = 14).

Relative expression to control.

Data with a different letter within a row are significantly different (P < .05).

Atheroprotective effects of BGA

To evaluate the effect of NO and SP supplementation on atherosclerosis development, we measured atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta and the aortic root. Both NO and SP supplementation significantly decreased aortic lesion area compared with control mice (Fig. 3A, B). While atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root were not significantly different between groups (Fig. 3C, D), CD68-positive areas in the aortic roots of NO- and SP-fed mice were significantly lower compared with control mice (Fig. 3E).

FIG. 3.

Antiatherogenic effects of BGA feeding in ApoE−/− mice fed an atherogenic diet or atherogenic diet supplemented with 5% NO or 5% SP for 12 weeks. (A) Representative aortas stained with Oil red O for visualization at 5× magnification. (B) Aortic lesion area expressed as % of total lesion area over total aortic surface area. Horizontal lines are means, and groups with a different letter are significantly different (P < .05). (C) Representative aortic root sections stained with Oil Red O and counterstained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (upper panel). CD68 immunostaining (lower panel). Quantification of lesions (D) and CD68 (E) in the aortic root. Data represent as mean ± SEM, and bars with a different letter are significantly different (P < .05). n = 10 for control, n = 12 for NO, and n = 14 for SP.

Discussion

Despite various health-promoting properties associated with BGA consumption, there has been limited understanding of underlying mechanisms of action. We previously reported that NO, but not SP, has a cholesterol-lowering effect in vivo,21 while both BGA exert anti-inflammatory effects ex vivo18 and in vitro.17,18 As hyperlipidemia and chronic inflammation facilitate atherogenesis, in this study, we evaluated if supplementation with BGA may protect against atherosclerotic lesion development using ApoE−/− mice, a well-known mouse model of atherosclerosis. Our results indicated that both BGA exerted a similar degree of atheroprotective effects although NO, but not SP, lowered plasma lipids, suggesting that NO and SP are likely to inhibit atherosclerosis by different mechanisms.

NO decreased plasma TC levels, which is consistent with our previous findings that 5% NO supplementation for 4 weeks significantly lowered plasma TC in male C57BL/6J mice fed a normal chow diet.16 The TC-lowering effect of NO in C57BL/6J mice was attributed to its inhibitory action in the intestinal cholesterol absorption, which led to increases in hepatic expression of SREBP-2 and HMGR, possibly due to its high fiber contents. Similar hypocholesterolemic effect of NO was also observed in rats fed a diet high in cholesterol with 5% NO supplementation.22 However, there was no significant decrease in the intestinal cholesterol absorption in ApoE−/− mice in the present study, where mice were challenged with an atherogenic HF/HC diet (data not shown). Reasons for the discrepancy between these two studies are not clear, but it may be related to different mouse models used. Sehayek et al.23 demonstrated that upon dietary cholesterol challenge, C57BL/6J mice decreased intestinal cholesterol absorption and increased biliary cholesterol, whereas ApoE−/− mice failed to inhibit intestinal cholesterol absorption, suggesting that apoE is likely to play an important role in the regulation of cholesterol absorption. Therefore, although mechanisms of action are elusive, it may be presumed that NO inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption in an apoE-dependent manner.

In mice fed an NO-supplemented diet, plasma TG levels were significantly lower than control and SP-fed mice. Although NO did not significantly alter liver TG levels, weights were significantly lower and fat accumulation was noticeably less in the livers of NO-fed mice compared with the other groups. However, hepatic expression of genes related to lipogenesis, that is, FAS and SCD-1, and fatty acid oxidation, that is, CPT-1α and ACOX-1, was not significantly different between the groups. Instead, we observed a significant decrease in hepatic FAS protein in NO-fed mice. Post-transcriptional regulation of FAS expression was observed in vitro, which increases protein degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome system.24 Therefore, the inhibitory action of NO in liver steatosis may be mediated, at least in part, by inhibiting lipogenesis using facilitated FAS protein degradation.

In contrast to the hypocholesterolemic and hypotriglycedemic effects of NO, we did not observe decreases in plasma TC or TG levels by SP in the present study. In mice fed a regular chow diet supplemented with 2.5% or 5% of SP, there was no significant lipid-lowering effect of SP in another of our studies, while NO decreased plasma TC and TG levels (article in preparation). Conflicting results on the effects of SP on plasma lipid levels have been reported. Plasma TC and TG concentrations were not significantly altered when male Wister albino rats consumed 300 mg/kg of SP for 60 days.25 In Long Evans rats fed a high-fat and high-sugar diet, supplementation of 0.5% or 2.5% SP for 4 weeks increased serum TG, while serum TC was significantly reduced by SP.26 It was demonstrated that SP supplementation significantly increased serum TC in ovariectomized female Wistar rats fed 0.08 g/kg BW of SP per day for 6 weeks, but serum TG was decreased with SP supplementation at 0.8 g/kg BW.27 When broiler chickens were fed a diet supplemented with 1% SP for 1 month, serum TC levels were decreased.28 Studies also demonstrated that New Zealand white rabbits fed a HC diet containing 5% SP15 or consumed 0.5 g of SP daily29 showed decreased serum TC levels. Therefore, the effects of SP on plasma TC and TG vary based on animal species, gender, dietary challenges, SP dosages, and duration of supplementation. Despite the inconsistency in lipid-lowering effects of SP observed in animal studies, hypolipidemic effects of SP have been reported in several clinical studies. Significant decreases in plasma TG and the ratios of TC:high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol as well as LDL cholesterol:HDL cholesterol were observed in type 2 diabetic patients who consumed 2 g/day of SP for 2 months.12 In another clinical study, 8 g of daily SP supplementation for 12 weeks significantly reduced plasma TG concentrations and blood pressure in type 2 diabetic patients with higher initial TG levels, whereas subjects with high initial TC and LDL cholesterol showed a significant reduction in TC and LDL cholesterol.30 Patients with hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome who consumed 1 g/day of SP for 2 months displayed significant decreases in plasma TC, LDL cholesterol, and TG concentrations.31 Therefore, studies have shown that SP supplementation improves circulating lipid profiles in humans.

Both NO and SP supplementation significantly decreased atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta. The antiatherogenic effect of NO is attributed to its lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory properties, as we demonstrated in our previous studies and the present study. In contrast, SP did not lower plasma TC and TG, but the extent of its atheroprotective effect was similar to NO supplementation. Previously, we demonstrated that NO and SP have anti-inflammatory effects ex vivo and in vitro. Splenocytes were isolated from ApoE−/− mice fed a HF/HC diet containing 5% NO or SP, which was the same diet used in the present study, and the cells were stimulated by LPS. IL-6 secretion from the splenocytes of NO- or SP-fed mice was significantly less compared with control mice.18 Furthermore, our previous study also demonstrated that NO and SP organic extracts markedly reduced mRNA expression as well as secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and IL-1β, through the inhibition of NF-κB pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages and in mouse bone marrow macrophages.17,18 Given the potent anti-inflammatory effect of SP, it can be presumed that SP supplementation may prevent atherogenesis by inhibiting inflammation without altering plasma lipids in ApoE−/− mice. Interestingly, SP has been consumed in indigenous countries to promote immunity and to protect against inflammation.9,32 Furthermore, studies have also shown anti-inflammatory effects of SP in animal models.33,34 In our study, there was less CD68-positive area in the aortic root of mice fed NO or SP than controls, although lesions were not significantly different among groups. In general, atherosclerotic lesions are formed in ApoE−/− mice fed a normal chow diet for 8–15 weeks, while a HF/HC diet drastically accelerates the formation of atherogenesis.35,36 As macrophages play critical roles not in the initial stage of atherogenesis but the progression of atherogenesis, it would be interesting to see if longer exposure to the BGA is able to inhibit progression of initial lesions to advanced complicated lesions/rupture in the aortic root of ApoE−/− mice.

Despite the health-promoting effects of NO and SP, bioactive compounds that exert the effects have not been well characterized. SP contains γ-linolenic acid,37–40 tocopherols,41 and carotenoids such as β-carotene40 and lutein.42 It has also been shown that C-phycocyanin (C-PC), a bioactive pigment in SP that has potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, protects liver from inflammation by inhibiting oxidation-induced NF-κB activation in Kupffer cells.43 These compounds in SP may be responsible for the atheroprotective effect by exerting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, as mounting evidence supports that inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress can prevent atherosclerosis.44 We also previously demonstrated that NO contains unsaturated fatty acids and β-carotene.16 However, it is not clear which compounds in NO and SP are responsible for their antiatherogenic effect. Therefore, future study is warranted to identify compounds in NO and SP that have lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory properties.

In conclusion, both NO and SP exert atheroprotective effects to a similar degree, although the underlying mechanisms of action for each BGA are presumed to be different. While NO supplementation is able to lower blood lipid and inflammation, the prevention of athesclerotic lesion development by SP is likely attributable to its potent anti-inflammatory properties. The Dietary Supplements Information Expert Committee of the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention has awarded SP a grade A safety rating and supports that SP is generally safe for human consumption.45 We also previously demonstrated that supplementation of 2.5% or 5% of NO or SP for 6 months in mice did not display any adverse side effects.46 Therefore, NO and SP may be developed as safe and effective natural products for atheroprotection. Human clinical studies need to be performed to determine if the consumption of the BGA provides health benefits to lower CHD in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R21AT005152 grant to J. Lee.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors read this article and claim no competing financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. : Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:e2–e220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. : The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 2002;288:2709–2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ooi EMM, Barrett PHR, Watts GF: The extended abnormalities in lipoprotein metabolism in familial hypercholesterolemia: developing a new framework for future therapies. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:1811–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A: Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002;105:1135–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber C, Noels H: Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med 2011;17:1410–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costopoulos C, Liew TV, Bennett M: Ageing and atherosclerosis: mechanisms and therapeutic options. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;75:1251–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamkhande PG, Chandak PG, Dhawale SC, Barde SR, Tidke PS, Sakhare RS: Therapeutic approaches to drug targets in atherosclerosis. Saudi Pharm J 2014;22:179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbaum D, Dallongeville J, Sabouret P, Bruckert E: Discontinuation of statin therapy due to muscular side effects: a survey in real life. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013;23:871–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciferri O: Spirulina, the edible microorganism. Microbiol Rev 1983;47:551–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Juneau P, Qiu B: Effects of three pesticides on the growth, photosynthesis and photoinhibition of the edible cyanobacterium Ge-Xian-Mi (Nostoc). Aquat Toxicol 2007;81:256–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regunathan C, Wesley SG: Pigment deficiency correction in shrimp broodstock using Spirulina as a carotenoid source. Aquaculture Nutr 2006;12:425–432 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parikh P, Mani U, Iyer U: Role of Spirulina in the Control of Glycemia and Lipidemia in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Med Food 2001;4:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madkour FF, Kamil AE-W, Nasr HS: Production and nutritive value of Spirulina platensis in reduced cost media. Egypt J Aquat Res 2012;38:51–57 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Kate BN, Banerjee UC: Bioactive compounds from cyanobacteria and microalgae: An overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2005;25:73–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheong SH, Kim MY, Sok DE, et al. : Spirulina prevents atherosclerosis by reducing hypercholesterolemia in rabbits fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 2010;56:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen HE, Blobaum KR, Jesch ED, et al. : Hypocholesterolemic effect of Nostoc commune var. sphaeroides Kutzing, an edible blue-green alga. Eur J Nutr 2009;48:387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park YK, Rasmussen HE, Ehlers SJ, et al. : Repression of proinflammatory gene expression by lipid extract of Nostoc commune var sphaeroides Kutzing, a blue-green alga, via inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Nutr Res 2008;28:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku CS, Pham TX, Park Y, et al. : Edible blue-green algae reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting NF-κB pathway in macrophages and splenocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1830:2981–2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim B, Ku CS, Pham TX, et al. : Aronia melanocarpa (chokeberry) polyphenol-rich extract improves antioxidant function and reduces total plasma cholesterol in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Nutr Res 2013;33:406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Seo JM, Nguyen A, et al. : Astaxanthin-Rich Extract from the Green Alga Haematococcus pluvialis Lowers Plasma Lipid Concentrations and Enhances Antioxidant Defense in Apolipoprotein E Knockout Mice. J Nutr 2011;141:1611–1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen HE, Blobaum KR, Park YK, Ehlers SJ, Lu F, Lee JY: Lipid extract of Nostoc commune var. sphaeroides Kutzing, a blue-green alga, inhibits the activation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins in HepG2 cells. J Nutr 2008;138:476–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hori K, Ishibashi G, Okita T: Hypocholesterolemic effect of blue-green alga, ishikurage (Nostoc commune) in rats fed atherogenic diet. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 1994;45:63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sehayek E, Shefer S, Nguyen LB, Ono JG, Merkel M, Breslow JL: Apolipoprotein E regulates dietary cholesterol absorption and biliary cholesterol excretion: studies in C57BL/6 apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci (PNAS) 2000;97:3433–3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Deng R, Zhu HH, et al. : Modulation of fatty acid synthase degradation by concerted action of p38 MAP kinase, E3 ligase COP1, and SH2-tyrosine phosphatase Shp2. J Biol Chem 2013;288:3823–3830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bashandy SA, Alhazza IM, El-Desoky GE, Al-Othman ZA: Hepatoprotective and hypolipidemic effects of Spirulina platensis in rats administered mercuric chloride. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 2011;5:175–182 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mridha MOF, Noor P, Khaton R, Islam D, Hossain M: Effect of Spirulina platensis on lipid profile of long evans rats. Bangladesh J Sci Ind Res 2010;45:249–254 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishimi Y, Sugiyama F, Ezaki J, Fujioka M, Wu J: Effects of spirulina, a blue-green alga, on bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats and hindlimb-unloaded mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2006;70:363–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dadgar H, Toghyani M, Dadgar M: Effect of dietary Blue-Green-Alga (Spirulina Platensis) as a food supplement on cholesterl, HDL, LDL cholesterol and triglyceride of broiler chicken. Eur J Pharmacol 2011;668 Suppl 1:e37 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colla LM, Muccillo-Baisch AL, Costa JAV: Spirulina platensis effects on the levels of total cholesterol, HDL and triacylglycerols in rabbits fed with a hypercholesterolemic diet. Braz Arch Biol Technol 2008;51:405–411 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee EH, Park JE, Choi YJ, Huh KB, Kim WY: A randomized study to establish the effects of spirulina in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Nutr Res Pract 2008;2:295–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samuels R, Mani UV, Iyer UM, Nayak US: Hypocholesterolemic effect of spirulina in patients with hyperlipidemic nephrotic syndrome. J Med Food 2002;5:91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng R, Chow TJ: Hypolipidemic, antioxidant, and antiinflammatory activities of microalgae Spirulina. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2010;28:e33–e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joventino IP, Alves HG, Neves LC, et al. : The microalga Spirulina platensis presents anti-inflammatory action as well as hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic properties in diabetic rats. J Complement Integr Med 2012;9:Article 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pak W, Takayama F, Mine M, et al. : Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of spirulina on rat model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2012;51:227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pendse AA, Arbones-Mainar JM, Johnson LA, Altenburg MK, Maeda N: Apolipoprotein E knock-out and knock-in mice: atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, and beyond. J Lipid Res 2009;50 Suppl:S178–S182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofker MH, van Vlijmen BJ, Havekes LM: Transgenic mouse models to study the role of APOE in hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1998;137:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das UN: From bench to the clinic: γ-linolenic acid therapy of human gliomas. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2004;70:539–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burri BJ: Beta-carotene and human health: a review of current research. Nutr Res 1997;17:547–580 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagaraj S, Arulmurugan P, Rajaram MG, et al. : Hepatoprotective and antioxidative effects of C-phycocyanin from Arthrospira maxima SAG 25780 in CCl4-induced hepatic damage rats. Biomed Prev Nutr 2012;2:81–85 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranga Rao A, Baskaran V, Sarada R, Ravishankar GA: In vivo bioavailability and antioxidant activity of carotenoids from microalgal biomass—A repeated dose study. Food Res Int 2013;54:711–717 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendiola JA, García-Martínez D, Rupérez FJ, et al. : Enrichment of vitamin E from Spirulina platensis microalga by SFE. J Supercritical Fluids 2008;43:484–489 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng YF, Bae SH, Kwon MJ, et al. : Inhibitory effects of astaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, canthaxanthin, lutein, and zeaxanthin on cytochrome P450 enzyme activities. Food Chem Toxicol 2013;59:78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Remirez D, Fernandez V, Tapia G, Gonzalez R, Videla LA: Influence of C-phycocyanin on hepatocellular parameters related to liver oxidative stress and Kupffer cell functioning. Inflamm Res 2002;51:351–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Diepen JA, Berbée JFP, Havekes LM, Rensen PCN: Interactions between inflammation and lipid metabolism: Relevance for efficacy of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2013;228:306–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marles RJ, Barrett ML, Barnes J, et al. : United States pharmacopeia safety evaluation of spirulina. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2011;51:593–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Park Y, Cassada DA, Snow DD, Rogers DG, Lee J: In vitro and in vivo safety assessment of edible blue-green algae, Nostoc commune var. sphaeroides Kutzing and Spirulina plantensis. Food Chem Toxicol 2011;49:1560–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]