Abstract

Knowledge of one’s own HIV status is essential for long-term disease management, but there are few data on how disclosure of HIV status to infected children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa is associated with clinical and psychosocial health outcomes. We conducted a detailed baseline assessment of the disclosure status, medication adherence, HIV stigma, depression, emotional and behavioral difficulties, and quality of life among a cohort of Kenyan children enrolled in an intervention study to promote disclosure of HIV status. Among 285 caregiver–child dyads enrolled in the study, children’s mean age was 12.3 years. Caregivers were more likely to report that the child knew his/her diagnosis (41%) compared to self-reported disclosure by children (31%). Caregivers of disclosed children reported significantly more positive views about disclosure compared to caregivers of non-disclosed children, who expressed fears of disclosure related to the child being too young to understand (75%), potential psychological trauma for the child (64%), and stigma and discrimination if the child told others (56%). Overall, the vast majority of children scored within normal ranges on screenings for behavioral and emotional difficulties, depression, and quality of life, and did not differ by whether or not the child knew his/her HIV status. A number of factors were associated with a child’s knowledge of his/her HIV diagnosis in multivariate regression, including older age (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.1), better WHO disease stage (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.4–4.4), and fewer reported caregiver-level adherence barriers (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.4). While a minority of children in this cohort knew their HIV status and caregivers reported significant barriers to disclosure including fears about negative emotional impacts, we found that disclosure was not associated with worse psychosocial outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, disclosure, adolescents, mental health, resource-limited setting

Introduction

There are approximately 3.2 million HIV-infected children under the age of 15 worldwide with over 90% living in sub-Saharan Africa (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). With the development of highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART), HIV-infected children can survive well into adolescence and adulthood (WHO, 2011a). A critical component of children’s transition into these new life periods is learning their HIV status (often known as “disclosure”), which is required to move into adult care settings and to take increasing responsibility for their disease management (Wiener, Mellins, Marhefka, & Battles, 2007). Recommendations for disclosure of HIV status to infected children advocate for a process of increasing information about HIV and their serostatus based on cognitive and emotional maturity (USAID, 2010; WHO, 2011b). A recent review of the literature on disclosure of HIV status to children found that children in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are less likely to know their status and to learn it at later ages compared to children from high-income countries (Pinzon-Iregui, Beck-Sague, & Malow, 2013).

It is unclear why disclosure happens less often and at later ages for children in LMIC and factors associated with a child being more or less likely to know their HIV status are not well described, particularly in LMIC (Vreeman, Gramelspacher, Gisore, Scanlon, & Nyandiko, 2013). Previous qualitative work in this setting suggests that caregiver-level fears about the psychological impacts of disclosure on children hinder disclosure efforts but that caregivers also believe that disclosure may be beneficial in other ways such as improving adherence to treatment (Vreeman et al., 2009, 2010). A better understanding of how both child and caregiver-level factors operate as facilitators and barriers of HIV disclosure to children are essential to inform guidelines and interventions to better support children, caregivers, and their health care providers. This manuscript provides a detailed description of baseline disclosure status, clinical characteristics, medication adherence, HIV-related stigma, depression, emotional and behavioral difficulties, quality of life, and school achievement from a cohort of Kenyan children enrolled in an intervention study to promote disclosure of HIV status.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study among a cohort of Kenyan children and their caregivers enrolled in an ongoing study to evaluate the effectiveness of a culturally adapted, multi-component intervention to support disclosure of HIV status to infected children. Children and their caregivers are being followed for two years, with intensive clinical and psychosocial assessments conducted at baseline and at six-month intervals thereafter. In addition to patient assessments, all participants are issued Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS®, MWV/AARDEX Inc.) for electronic dose monitoring of HAART. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA and by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee at Moi University School of Medicine in Eldoret, Kenya.

Setting and population

This study is being conducted at eight health facilities of the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) – a large HIV treatment program in western Kenya (Einterz et al., 2007; Inui et al., 2007). Disclosure protocols at AMPATH recommend initiating disclosure to children at the age of 10 and implementing full disclosure before the age of 14 when children are transferred to adult care. AMPATH clinical staff undergo annual training on disclosure of HIV status to children, including training on various strategies to initiate the disclosure process for of-age children and disclosure counseling; however, a formal review of how and if these protocols are being implemented appropriately has not been conducted. There are not counselors at AMPATH clinics with dedicated time to assist with or perform disclosure. The impact of having these counselors in place is a major component of the disclosure intervention being tested.

Convenience sampling was employed to recruit 35 children at each of the eight facilities from March 2013 to September 2013. Random sampling was not feasible due to the small number of children in the target age group at each facility. Eligibility criteria for children were: being 10–14 years of age, HIV-infected, and on first-line or second-line HAART. The child’s disclosure status was not considered for enrollment. There were no exclusion criteria for caregivers, as long as they reported being involved in the child’s medical care. Children and their caregivers were referred to the study team by clinical staff (nurses and clinicians) or self-referred to the study team through study fliers placed in participating health facilities.

Measures

At baseline, each participant was administered a set of questionnaires by trained study staff. Questionnaires were administered in the same order for all participants and were given in Swahili or English depending on the participant’s preference. Participants’ answers were recorded on a paper form, which was then entered into a REDCap database (Harris et al., 2009). Demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from the child’s medical file using a standardized paper clinical extraction tool and entered into REDCap. WHO disease stage was defined as worst-ever reported disease stage.

Disclosure questionnaire

A disclosure questionnaire was administered separately to all children and caregivers. The questionnaire was developed in this setting through previous qualitative work (Vreeman et al., 2010). Questionnaire items included the child’s disclosure status, as well as questions about the disclosure process, preferences, and fears, with variations in the child and caregiver questionnaire versions. All children and caregivers completed the disclosure questionnaires, with children who indicated they knew their HIV status answering additional questions about the disclosure process and preferences. Study personnel were specifically trained to assess a child’s disclosure status through multiple strategies, including speaking with the child, caregiver, and other clinical staff to protect against inadvertent disclosure. A child was only considered “disclosed” and asked additional questions that referred to HIV if the study personnel had received confirmation of disclosure from the child and their caregiver.

Adherence questionnaire

The adherence questionnaire was developed and validated in this setting through previous qualitative and quantitative work and included questions about missed doses, barriers to adherence, and medication taking behaviors (Vreeman, Nyandiko, Ayaya, Walumbe, & Inui, 2014; Vreeman, Nyandiko, Liu, et al., 2014; Vreeman, Wiehe, Pearce, & Nyandiko, 2008; Vreeman et al., 2009). The adherence questionnaire was administered either to the child only (when the child and caregiver reported the child had full responsibility for medication taking), the caregiver only (when the child and caregiver reported the caregiver had full responsibility), or both the child and caregiver (if there was shared responsibility). An overall adherence variable was not created for this analysis; each adherence questionnaire item was individually assessed in univariate analysis for its association with disclosure status. Adherence variables can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Adherence, stigma, and psychosocial correlates of disclosure status.

| Mean (standard deviation) or frequency count (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Overall (n = 285) | Non-disclosed (n = 163) | Disclosed (n= 122) | P value |

| Adherence variables | ||||

| Who gives the child medicines | ||||

| Mother | 121 (43%) | 76 (47%) | 45 (37%) | .10 |

| Father | 27 (10%) | 18 (11%) | 9 (7%) | .29 |

| Aunt/uncle | 30 (11%) | 17 (10%) | 13 (11%) | .95 |

| Grandparent | 21 (7%) | 12 (7%) | 9 (7%) | .99 |

| Child takes own | 190 (67%) | 106 (65%) | 84 (69%) | .50 |

| Problems taking ART | 25 (9%) | 14 (9%) | 11 (9%) | .90 |

| Problems taking ART on time | 63 (22%) | 39 (24%) | 24 (20%) | .39 |

| Child-level barriers to taking ART | 123 (43%) | 77 (47%) | 46 (38%) | .11 |

| Caregiver-level barriers to taking ART | 94 (33%) | 63 (39%) | 31 (25%) | .02 |

| Clinic-level barriers to taking ART | 69 (24%) | 43 (26%) | 26 (21%) | .32 |

| Took one or more late doses in the past seven days | 82 (29%) | 48 (30%) | 34 (28%) | .70 |

| Missed one or more doses in the past seven days | 50 (18%) | 31 (20%) | 19 (16%) | .41 |

| Missed one or more doses in the past 30 days | 54 (20%) | 29 (18%) | 25 (21%) | .58 |

| HIV stigma variables | ||||

| Caregiver stigma score | 3.4 (3.3) | 3.4 (3.2) | 3.5 (3.4) | .79 |

| Child stigma score | n/a | n/a | 3.3 (2.1) | n/a |

| GHAC QoL domain scores | ||||

| General health | 78.3 (16.5) | 77.8 (16.8) | 78.9 (16.1) | .59 |

| Physical functioning | 88.0 (19.9) | 88.4 (18.8) | 87.3 (21.3) | .64 |

| Psychological well-being | 89.1 (10.6) | 89.9 (10.5) | 88.0 (10.7) | .14 |

| Health utilization | 99.2 (2.8) | 99.3 (2.7) | 99.2 (3.0) | .74 |

| Health symptoms | 89.7 (10.7) | 88.4 (11.6) | 91.4 (9.2) | .02 |

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | ||||

| SDQ total difficulties score | .93 | |||

| Normal | 260 (92%) | 148 (91%) | 112 (92%) | |

| Borderline disorder | 11 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Abnormal | 13 (5%) | 8 (5%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Patient Health Questionnaire – Depression Screening | ||||

| PHQ-9 score | .57 | |||

| No depression | 227 (81%) | 130 (81%) | 97 (81%) | |

| Minimal symptoms | 41 (15%) | 24 (15%) | 17 (14%) | |

| Minor depression | 7 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Major depression | 6 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (3%) | |

Stigma questionnaire

A 17-item stigma questionnaire was administered to all caregivers, which asked caregivers to agree or disagree with a number of statements about their and their child’s experiences with HIV stigma. The questionnaire was developed by investigators in this setting and informed by literature reviews conducted by other investigators (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, 2009; Steward et al., 2008). A 10-item stigma questionnaire was administered to children who indicated they knew their HIV status, as questions implied HIV infection. Raw scores were computed for stigma questionnaires with a higher score indicating higher levels of stigma.

Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) General Health Assessment for Children (GHAC) Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire

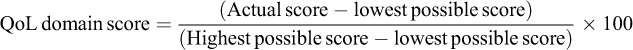

All caregivers completed the multi-domain PACTG GHAC QoL questionnaire (Gortmaker, Lenderkin, & Clark, 1998; Lee, Gortmaker, McIntosh, Hughes, & Oleske, 2006; Lenderking, Testa, Katzenstein, & Hammer, 1997). A raw score was computed as an algebraic sum for each of the following QoL domains: general health, physical functioning, psychological well-being, health utilization, and physical symptoms (Gortmaker et al., 1998). A higher score indicated a more positive health outcome, which required reverse coding of some questionnaire items. Transformation of raw scores to a 0–100 point scale was conducted, as done elsewhere (Bele, Valsangkar, & Bodhare, 2011; Butler et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2006). The following formula was used:

|

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) – Youth Version

All children completed the single-sided SDQ – Youth Version – a 25-item behavioral screening questionnaire designed for adolescents aged 11–16 years that asks about physical and psychological well-being over the past six months (Goodman, Meltzer, & Bailey, 1998; Goodman, Renfrew, & Mullick, 2000). The questionnaire is comprised of five domains (of five items each): emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial. A “total difficulties score” was calculated using all scales except prosocial, and the resultant score ranges were from 0–40. A three-band categorization method was used to classify participants’ score as “normal” (score of 0–15), “borderline” (score of 16–19), and “abnormal” (score of 20–40) as defined elsewhere (Goodman et al., 1998, 2000).

Patient Health Questionnaire – 9-item depression instrument (PHQ-9)

All children completed the standard PHQ-9, a 9-item questionnaire about depression symptoms in the past two weeks. Raw PHQ-9 scores were calculated and score ranges were defined as “no depression” (score of 0–4), “minimal depression” (score of 5–9), “mild major depression” (score of 10–14), “moderate major depression” (score of 15–19), and “severe major depression” (score >20; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). While designed for adults, the PHQ-9 has shown good sensitivity and specificity among adolescents older than 12 years and among HIV-infected adolescents specifically, although with a higher optimal cut point for depression (Leahy, Barton, & Graper, 2012; Richardson et al., 2010).

Missing data

In cases where caregivers or children did not complete ≥1 item in a domain, missing values were computed using the mean value of non-missing values (Little & Rubin, 2002). Missing values were rare with no individual variable having >2% missing data, and no participant failed to respond to >2 questions in a domain or questionnaire.

Analysis

Internal consistency and reliability were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) where appropriate. Cronbach’s α was calculated for the stigma questionnaire, QoL, SDQ, and PHQ-9 (and of individual domains for the QoL and SDQ). Univariate analysis using Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests for continuous variables were performed to investigate demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics by disclosure status. Disclosure status was defined by any indication from the caregiver or child that the child knew his/her HIV status, which was assessed by multiple questions about the child knowing the name of his/her illness and why s/he came to clinic or took medicines. Variables significant in univariate analyses (p< .05) along with key demographic variables (age, gender, and orphan status) were included in multivariate logistic regression. Demographic variables (e.g., age) were investigated for interactions with clinical, psychosocial, and adherence variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 22.0 (IBM Corp, 2013).

Results

Child and caregiver participant characteristics

A total of 285 caregiver–child dyads completed a baseline evaluation. The mean age of child participants was 12.3 years (standard deviation: 1.5) and 52% were female (Table 2). Children had a mean CD4% of 26.4% (standard deviation: 10.4%) and had been on HAART for an average of 4.4 years (standard deviation: 2.4). The majority of caregiver participants were the biological mother of the child (53%). Only two children (1%) were not enrolled in school, but 34% of caregivers reported their child was limited in school because of HIV due to developmental delays, being held back a grade level, or not being able to participate in normal school activities such as sports. At baseline, 43% of children knew their HIV status per caregiver or child report (i.e., either the caregiver or the child reported knowing HIV status). There was significant discordance between caregiver and child reported disclosure status with 43 caregiver–child dyads (15%) having discordant responses. Caregivers were more likely to report that the child knew his/her HIV status (41%) compared to self-reported disclosure status by children (31%); while 35 caregivers reported the child knew his/her HIV status and the child reported not knowing, only eight children reported knowing their HIV status and the caregiver reported that the child did not know. Among children who knew their status by caregiver or child report, caregivers reported a mean age at disclosure of 10.1 years (range: 6–14).

Table 2. Study participants’ characteristics.

| Mean (standard deviation) or frequency count (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Overall (n= 285) | Non-disclosed (n= 163) | Disclosed (n= 122) | P valuea |

| Age (years) | 12.3 (1.5) | 11.8 (1.3) | 13.0 (1.5) | <.001 |

| CD4% | 26.4 (10.4) | 27.4 (9.9) | 25.2 (10.9) | .08 |

| Duration on antiretroviral therapy (years) | 4.4 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.3) | 4.3 (2.5) | .60 |

| Gender (female) | 147 (52%) | 84 (52%) | 63 (52%) | .99 |

| Ethnic group | .63 | |||

| Luhya | 109 (39%) | 57 (36%) | 52 (43%) | |

| Kalenjin | 76 (27%) | 43 (27%) | 33 (27%) | |

| Luo | 52 (18%) | 31 (19%) | 21 (17%) | |

| Kikuyu | 36 (13%) | 24 (15%) | 12 (10%) | |

| Other | 8 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 3 (2%) | |

| WHO Stage (using worst reported disease stage) | 0.02 | |||

| 1 | 89 (31%) | 47 (29%) | 42 (34%) | |

| 2 | 90 (32%) | 42 (26%) | 48 (39%) | |

| 3 | 93 (33%) | 66 (41%) | 27 (22%) | |

| 4 | 10 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 4 (3%) | |

| Orphan status | ||||

| Both parents dead | 141 (50%) | 81 (50%) | 60 (49%) | .85 |

| Mother dead | 89 (31%) | 55 (34%) | 34 (27.9%) | .29 |

| Father dead | 90 (32%) | 54 (33%) | 36 (30%) | .52 |

| Sibling(s) has HIV | 52 (20%) | 32 (21%) | 20 (18%) | .46 |

| Enrolled in school | 279 (99%) | 159 (99%) | 120 (99%) | .84 |

| Caregiver at assessment | .83 | |||

| Biological mother | 152 (53%) | 87 (54%) | 65 (53%) | |

| Aunt/uncle | 39 (14%) | 22 (14%) | 17 (14%) | |

| Adoptive parent | 30 (11%) | 20 (12%) | 10 (8%) | |

| Biological father | 25 (9%) | 15 (9%) | 10 (8%) | |

| Grandparent | 18 (6%) | 9 (6%) | 9 (7%) | |

| Sibling | 13 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Other | 7 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (3%) | |

a P values were computed using Student’s t tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Caregiver perspectives on disclosure

Caregivers who had already disclosed to their child had more positive views about disclosure, including the child and caregiver being more prepared for disclosure and that the benefits of disclosure outweighed the risks (Table 3). The most common reasons caregivers of non-disclosed children gave for not disclosing were that the child was too young to understand (75%), potential psychological trauma for the child (64%), and a fear of stigma and discrimination (56%). These fears were rarely reported as significant problems by caregivers who had disclosed. Eighty-two percent of caregivers reported that disclosure was helpful for the child, including that disclosure improved adherence to medication (97%) and the relationship with the caregiver (79%).

Table 3. Caregivers’ preferences for and experiences of disclosure to children.

| Percent of caregivers who agreed with statement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers who had NOT disclosed (n= 163) | Caregivers who had disclosed (n = 122) | P value | |

| Variables from the Disclosure Questionnaire | |||

| My child is/was ready for disclosure | 107 (67%) | 101 (84%) | .002 |

| My child needs/needed to know his/her status | 134 (83%) | 116 (96%) | .001 |

| I feel/felt prepared to tell my child | 96 (57%) | 107 (90%) | <.001 |

| It is/was very important to me that I am the one to tell my child so that they do not hear about their status from someone else | 138 (86%) | 109 (91%) | .20 |

| I feel/felt supported by my child’s health-care provider to disclose to the child | 134 (84%) | 108 (91%) | .09 |

| I think/thought the child would be motivated to take their medications if they knew their diagnosis | 125 (79%) | 110 (92%) | .004 |

| I feel prepared to answer questions that my child might have about his/her illness | 145 (90%) | 111 (92%) | .63 |

| I worry my child will lose hope or focus on dying because they know their diagnosis | 44 (28%) | 20 (16%) | .03 |

| I worry about the risk of stigma if my child were to tell others about his/her diagnosis | 51 (32%) | 29 (24%) | .16 |

| I think the benefits of telling my child about his/her diagnosis outweighs/outweighed the possible risks | 136 (85%) | 114 (93%) | .02 |

| I was the one who made the decision to disclose to my child | n/a | 84 (77%) | n/a |

| Variables from the GHAC QoL Infection Status domain | |||

| What are your reasons for not telling your child his/her diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| My child is too young | 131 (75%) | ||

| I do not want my child to be sad or depressed | 112 (64%) | ||

| My child could tell people who should not know | 98 (56%) | ||

| I don’t want my child to be afraid of death | 90 (52%) | ||

| The family will be less stressed | 62 (36%) | ||

| My child will be happier not knowing | 84 (48%) | ||

| I do not want my child left out or discriminated against | 97 (56%) | ||

| Are any of the following problems because your child does not know his/her diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| My child is unsure why he/she is coming to a special clinic/doctor | 113 (65%) | ||

| My child knows I am not telling the truth about his/her illness | 46 (26%) | ||

| My child is less cooperative with medical care or taking medicines | 23 (13%) | ||

| My child does not know how to be responsible for not infecting others | 95 (55%) | ||

| My child’s behavior is worse due to not knowing | 2 (1%) | ||

| How does your child feel about life with his/her medical condition: | n/a | n/a | |

| Sad | 25 (15%) | ||

| Content/glad | 118 (69%) | ||

| Frightened | 18 (10%) | ||

| In control | 108 (63%) | ||

| Angry | 24 (14%) | ||

| Who encouraged you to discuss the diagnosis with your child: | n/a | n/a | |

| I encouraged it | 37 (33%) | ||

| Other family members | 8 (7%) | ||

| Child asking questions | 2 (2%) | ||

| Health-care provider | 68 (61%) | ||

| Who participated in the discussion of the child’s diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| I participated | 77 (69%) | ||

| Other family members | 33 (30%) | ||

| Health-care provider | 39 (35%) | ||

| How did you feel about the discussion of the child’s diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| I felt the discussion was helpful for my child | 92 (82%) | ||

| I felt we had enough support from the health-care team | 76 (68%) | ||

| I felt my child understood what was explained | 71 (63%) | ||

| I did not feel my child understood what was explained | 3 (3%) | ||

| I did not feel the health-care team was helpful enough | 6 (5%) | ||

| I felt the discussion was too difficult for my child | 11 (10%) | ||

| I was not present for the discussion | 16 (14%) | ||

| What has been good about your child knowing his/her diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| He/she is more cooperative about medical care and taking medicine | 107 (97%) | ||

| He/she is more open with family and friends | 66 (60%) | ||

| He/she understands why he/she is sick | 101 (92%) | ||

| He/she understands responsibility to avoid infecting others | 68 (62%) | ||

| Telling him/her the truth has improved our relationship | 87 (79%) | ||

| Are any of the following problems because your child knows his/her diagnosis: | n/a | n/a | |

| My child told friends, neighbors, or others who shouldn’t know | 9 (8%) | ||

| My child told family members who shouldn’t know | 9 (8%) | ||

| My child is sad or depressed | 5 (5%) | ||

| My child is afraid of death | 24 (22%) | ||

| My child’s behavior is worse | 1 (1%) | ||

| My child is less cooperative with medical care or taking medicines | 15 (14%) | ||

| My child has been left out or discriminated against | 1 (1%) | ||

| When your child was first told his/her diagnosis, was he/she: | n/a | n/a | |

| Sad | 40 (37%) | ||

| Content/glad | 45 (41%) | ||

| Frightened | 30 (27%) | ||

| Relieved | 73 (66%) | ||

| Angry | 20 (18%) | ||

| How does your child feel now about life with his/her medical condition: | n/a | n/a | |

| Sad | 9 (8%) | ||

| Content/glad | 85 (77%) | ||

| Frightened | 11 (10%) | ||

| In control | 88 (80%) | ||

| Angry | 6 (5%) | ||

Children’s adherence, physical, and psychological health

Children experienced significant barriers to adherence at the level of the child (43%), caregiver (33%), and clinic (24%). Missed doses in the past seven and 30 days were common with 18% of children reporting a missed dose in the past seven days and 20% in the past 30 days. Caregivers reported lower levels of HIV stigma for themselves and their child (mean stigma score of 3.4 out of 17) compared to children who reported higher levels of stigma (mean stigma score of 3.3 out of 10). Mean QoL scores indicated high levels of physical and psychological functioning of children in this cohort, and few children scored outside the normal range of the SDQ (4% scored in the “borderline” range and 5% in the “abnormal” range). Depressive symptoms were more common, with 15% of children having minimal, 3% having minor, and 2% having major depressive symptoms.

Patterns and correlates of disclosure status

In univariate analysis, the child’s older age (p< .001), better WHO stage (1 or 2 versus 3 or 4; p= .02), caregiver reporting fewer physical health symptoms (physical health QoL domain; p= .02), and fewer caregiver-level adherence barriers (p= .02) were all significantly associated with the child’s knowledge of his/her HIV status. Only the child’s older age (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.1), better WHO stage (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.4–4.4), and fewer caregiver-level adherence barriers (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.4) were predictive of disclosure in multivariate regression analysis (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with disclosure in multivariate regression.

| Variables | P value from univariate analysis | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s older age (years) | <.001 | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) |

| WHO stage 1 or 2 versus 3 or 4 | .02 | 2.5 (1.4–4.4) |

| Fewer caregiver-level adherence barriers | .02 | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) |

| Fewer caregiver reported physical health symptoms | .02 | NS |

Note: Child gender and orphan status were also included in the multivariate regression model but were not significant in univariate or multivariate regression analysis.

NS, not significant (i.e., 95% confidence interval included 1) in multivariate regression.

Internal consistency of instruments

The instruments used to evaluate stigma, QoL, behavioral problems, and depression showed moderate to good levels of internal consistency using Cronbach’s α. The caregiver stigma questionnaire showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .849), as did the QoL domains with Cronbach’s α on the various domains ranging from .807 (general health) to .867 (physical symptoms). The PHQ-9 and SDQ showed relatively good reliability overall (Cronbach’s α = .779 and .746, respectively); however, SDQ domains performed more poorly (Cronbach’s α ranged from .259 to .644).

Discussion

We found just over 40% of 10 to 14-year-olds knew their HIV status by caregiver report, which is similar to a previous study in this setting (Vreeman, Scanlon, et al., 2014) and similar to estimates from other LMIC (Vreeman et al., 2013). Given that more than half of children over 10 still do not know their status, the current disclosure protocol in place at AMPATH has clearly not been effectively implemented. There are likely several health systems factors that contribute to the ineffectiveness of the current disclosure protocol, including busy caseloads for clinicians that do not allow for enough time to assess disclosure readiness and conduct disclosure counseling in routine care and inadequate training and tools to use for disclosure counseling. Lack of caregiver readiness and fears about negative child-level (e.g., psychological distress) and family-level (e.g., stigma and discrimination) consequences of disclosure certainly contribute to a reluctance to disclose, as this and previous work among Kenyan caregivers suggest (Vreeman et al., 2010). While there were no differences in reported missed doses, disclosed children reported significantly fewer caregiver-level adherence barriers. While we cannot assess the relationship between disclosure and adherence given the cross-sectional nature of this study, the role that disclosure plays in reducing adherence barriers at the child and caregiver level has been supported by previous qualitative work in this setting (Vreeman et al., 2009, 2010) and others (Bikaako-Kajura et al., 2006). Using the longitudinal data we are collecting on disclosure status and adherence to HAART over two years of follow-up with this cohort, we will be able to provide more data to investigate the relationship between disclosure and adherence in the future.

Overall, children in this cohort demonstrated few psychosocial health problems and scored in the normal ranges of screenings for psychological functioning, behavioral and emotional difficulties, and depression symptoms, and did not differ by disclosure status. There are few studies on psychosocial health and QoL among HIV-infected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa (Mabugu, Revill, & van den Berg, 2013). A number of studies among Kenyan adolescents have found high rates of depression and anxiety, with one study finding 41% of adolescents admitted to inpatient and outpatient wards had indications of mild to moderate depression using the Children’s Depression Inventory (Ndetei, Khasakhala, Mutiso, & Mbwayo, 2009; Ndetei et al., 2008), but none of these studies focused on mental health among HIV-infected adolescents. A study from the USA among similarly aged HIV-infected adolescents using the same GHAC QoL scoring criteria that was used in this study showed generally high physical and psychological health functioning that was comparable to what we report (Butler et al., 2009). Few studies have investigated the psychological impact of disclosure on adolescents, but studies like this one and others have not found increased psychological problems among disclosed children (Butler et al., 2009; Mellins et al., 2002) with one study reporting disclosed children scored lower on depression and anxiety measures compared to non-disclosed children (Riekert, Wiener, & Battles, 1999).

Older children and adolescents have significantly more AIDS-related mortality compared to younger children and young adults in LMIC (Porth, Suzuki, Gillespie, Kasedde, & Idele, 2014). We found that disclosed children actually had better WHO disease stage overall, but we did not find significant correlations between disclosure and CD4%, hospitalizations, and health utilization. Studies on the association between disclosure status and clinical outcomes like virologic outcomes and disease progression have shown conflicting results (Ferris et al., 2007; Mellins et al., 2002; Sirikum, Sophonphan, Chuanjaroen, Lakonphon, & Srimuan, 2013). We found that caregivers of disclosed children reported significantly fewer physical health symptoms compared to caregivers of non-disclosed children, which may be due to their less advanced disease stage. Increased physical symptoms reported by caregivers of non-disclosed children may also be manifestations of psychosocial or emotional challenges such as depression or anxiety presenting as general physical complaints. This is a known phenomenon in children; a number of studies have found associations between psychosocial problems in children like depression, anxiety, and behavioral problems and physical symptoms (Campo, Jansen-McWilliams, Comer, & Kelleher, 1999; Campo et al., 2004; Dorn et al., 2003; Egger, Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 1999; Garber, Zeman, & Walker, 1990; Watson et al., 2003) although there is conflicting evidence about how common this is (Song et al., 1998; Walker, Garber, & Greene, 1993; Walker & Greene, 1989). In a setting where expressing mental health symptoms such as depression or anxiety may not be culturally acceptable or where cross-cultural performance of instruments to evaluate emotional and mental health symptoms may not be adequate, these general health complaints may reflect additional areas of concern for non-disclosed children (Simon, VonKorff, Piccinelli, Fullerton, & Ormel, 1999).

This study has several limitations. First, while we attempted to use validated, reliable instruments, most have not been validated in East Africa or in the adolescent population (Monahan et al., 2009; Omoro, Fann, Weymuller, Macharia, & Yueh, 2006). This leads to some uncertainty about whether children are experiencing any mental health issues or whether the instruments are performing adequately. Nonetheless, detailed evaluations of mental, emotional, and behavioral functioning, as well as QoL, are generally lacking for this population and this manuscript reports a comprehensive inventory that can be used for future validation work. We also calculated Cronbach’s α for the instruments and various domains tested that overall showed good internal consistency. Second, these data are limited to a cross-sectional sampling that precludes drawing conclusions about causation; however, the ongoing study’s longitudinal evaluations will allow us to better answer the important questions about the impact of disclosure over time. We also used convenience sampling based on clinical staff referral or self-referral for enrollment; it is possible that children and their caregivers who agreed to participate in the study differed in important ways compared to those who declined participation or did not self-refer. We did not collect data on subjects who declined participation as this is often viewed with suspicion in this clinical population, and thus could not assess differences among those who declined and agreed to participate. Third, we did see discrepancies between caregivers’ and children’s reports of disclosure. This may be related to the strong mandate to children not to report their HIV status to anyone, resulting in incorrect reporting to study personnel. This also might reflect incomplete disclosure to children, where indirect communication about HIV or discomfort with open discussion leads caregivers to think that disclosure has been carried out when, in fact, children have not grasped the full understanding of their diagnosis.

Conclusion

As the world’s cohorts of HIV-infected children reach adolescence, we face a critical need to support youth and their families through the process of disclosure. This detailed evaluation of a cohort of HIV-infected Kenyan children suggests that undergoing disclosure does not increase their mental, emotional, or behavioral distress. In contrast, disclosure was tied with a positive outlook on the part of the involved caregivers. Despite the potential for positive benefits to informing a child about their HIV status, a majority of older children and adolescents still do not know their status and are in need of disclosure counseling and services. Supporting families through the child disclosure process and finding ways to promote child physical and psychosocial health through this pivotal time of transition should be important targets for clinical care systems, particularly those in LMIC where millions of HIV-infected children will be entering adolescence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Josphine Aluoch’s work in the preparation of the study and data collection. Most of all, we would like to thank the children and caregivers for their willingness to donate their time and effort to participate in this study.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a grant entitled “Patient-Centered Disclosure Intervention for HIV-Infected Children [1R01MH099747-01] to Dr. Rachel Vreeman by the National Institute for Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Disclosure statement

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Indiana University School of Medicine or the Moi University School of Medicine. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Bele S. D., Valsangkar S., Bodhare T. N. Impairment of nutritional, educational status, and quality of life among children infected with and belonging to families affected by human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Research, Policy and Care. 2011:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Bikaako-Kajura W., Luyirika E., Purcell D. W., Downing J., Kaharuza F., Mermin J., …, Bunnell R. Disclosure of HIV status and adherence to daily drug regimens among HIV-infected children in Uganda . AIDS and Behavior. 2006;(Suppl. 4):S85–S93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A. M., Williams P. L., Howland L. C., Storm D., Hutton N., Seage G. R., Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group C. Study Team Impact of disclosure of HIV infection on health-related quality of life among children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2009:935–943. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo J. V., Bridge J., Ehmann M., Altman S., Lucas A., Birmaher B., …, Brent D. A. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004:817–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo J. V., Jansen-McWilliams L., Comer D. M., Kelleher K. J. Somatization in pediatric primary care: Association with psychopathology, functional impairment, and use of services. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999:1093–1101. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn L. D., Campo J. C., Thato S., Dahl R. E., Lewin D., Chandra R., Di Lorenzo C. Psychological comorbidity and stress reactivity in children and adolescents with recurrent abdominal pain and anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;(1):66–75. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V. A., Chaudoir S. R. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and Behavior. 2009:1160–1177. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger H. L., Costello E. J., Erkanli A., Angold A. Somatic complaints and psychopathology in children and adolescents: Stomach aches, musculoskeletal pains, and headaches. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999:852–860. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einterz R. M., Kimaiyo S., Mengech H. N., Khwa-Otsyula B. O., Esamai F., Quigley F., Mamlin J. J. Responding to the HIV pandemic: The power of an academic medical partnership. Academic Medicine. 2007:812–818. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180cc29f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris M., Burau K., Schweitzer A. M., Mihale S., Murray N., Preda A., …, Kline M. The influence of disclosure of HIV diagnosis on time to disease progression in a cohort of Romanian children and teens. AIDS Care. 2007:1088–1094. doi: 10.1080/09540120701367124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J., Zeman J., Walker L. S. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: Psychiatric diagnoses and parental psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990:648–656. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R., Meltzer H., Bailey V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;(3):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R., Renfrew D., Mullick M. Predicting type of psychiatric disorder from Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scores in child mental health clinics in London and Dhaka. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;(2):129–134. doi: 10.1007/s007870050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker S. L., Lenderkin W. R., Clark C. Development and use of a pediatric quality of life questionnaire in AIDS clinical trials: Reliability and validity of the General Health Assessment for Children (GHAC. In: Drotar D., editor. Measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: Implications for research, practice, and policy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J. G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, NY: Author.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Inui T. S., Nyandiko W. M., Kimaiyo S. N., Frankel R. M., Muriuki T., Mamlin J. J., …, Sidle J. E. AMPATH: Living proof that no one has to die from HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007:1745–1750. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0437-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy M., Barton T., Graper J. Diagnostic validity of the PHQ-A in assessing depressive disorders in an HIV-positive adolescent population. Washington, DC: 2012. Paper presented at the 19th International AIDS Conference, Abstract No. MOPE392. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. M., Gortmaker S. L., McIntosh K., Hughes M. D., Oleske J. M. Quality of life for children and adolescents: Impact of HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment. Pediatrics. 2006:273–283. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenderking W. R., Testa M. A., Katzenstein D., Hammer S. Measuring quality of life in early HIV disease: The modular approach. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 1997:515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018408115729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R. J. A., Rubin D. B. Statistical analysis with missing data. Vol. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mabugu T., Revill P., van den Berg B. The methodological challenges for the estimation of quality of life in children for use in economic evaluation in low-income countries. Value in Health Regional Issues. 2013:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins C., Brackis-Cott E., Dolezal C., Richards A., Nicholas S., Abrams E. Patterns of HIV status disclosure to perinatally HIV-infected children and subsequent mental health outcomes. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002:101–114. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007001008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan P. O., Shacham E., Reece M., Kroenke K., Ong’or W. O., Omollo O., …, Ojwang C. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndetei D. M., Khasakhala L. I., Mutiso V. N., Mbwayo A. W. Recognition of depression in children in general hospital-based paediatric units in Kenya: Practice and policy implications. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2009:25. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndetei D. M., Khasakhala L. I., Nyabola L., Ongecha-Owuor F., Seedat S., Mutiso V., …, Odhiambo G. The prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and syndromes in Kenyan children and adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;(1):33–51. doi: 10.2989/JCAMH.2008.20.1.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoro S. A., Fann J. R., Weymuller E. A., Macharia I. M., Yueh B. Swahili translation and validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2006:367–381. doi: 10.2190/8W7Y-0TPM-JVGV-QW6M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzon-Iregui M. C., Beck-Sague C. M., Malow R. M. Disclosure of their HIV status to infected children: A review of the literature. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2013;(2):84–89. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porth T., Suzuki C., Gillespie A., Kasedde S., Idele P. Disparities and trends in AIDS mortality among adolescents living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries. Melbourne: 2014. Paper presented at the 20th International AIDS Conference, [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L. P., McCauley E., Grossman D. C., McCarty C. A., Richards J., Russo J. E., …, Katon W. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010:1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekert K. A., Wiener L., Battles H. B. Prediction of psychological distress in school-age children with HIV. Children’s Health Care. 1999:201–220. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc2803_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. E., VonKorff M., Piccinelli M., Fullerton C., Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999:1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirikum C., Sophonphan J., Chuanjaroen T., Lakonphon S., Srimuan A. HIV disclosure and its effects of treatment outcomes in HIV-infected Thai children and adolescents. Kuala Lumpur: 2013,. Paper presented at the 5th International Workshop on HIV Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Song K. M., Morton A. A., Koch K. D., Herring J. A., Browne R. H., Hanway J. P. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1998:576–581. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward W. T., Herek G. M., Ramakrishna J., Bharat S., Chandy S., Wrubel J., Ekstrand M. L. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Social Science and Medicine. 2008:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID. South to South: Disclosure process for children and adolescents living with HIV: Practical guide. Bellville: Faculty of Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Gramelspacher A. M., Gisore P. O., Scanlon M. L., Nyandiko W. M. Disclosure of HIV status to children in resource-limited settings: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013:18466. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Nyandiko W. M., Ayaya S. O., Walumbe E. G., Inui T. S. Cognitive interviewing for cross-cultural adaptation of pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence measurement items. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014:186–196. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Nyandiko W. M., Ayaya S. O., Walumbe E. G., Marrero D. G., Inui T. S. Factors sustaining pediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in western Kenya. Qualitative Health Research. 2009:1716–1729. doi: 10.1177/1049732309353047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Nyandiko W. M., Ayaya S. O., Walumbe E. G., Marrero D. G., Inui T. S. The perceived impact of disclosure of pediatric HIV status on pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence, child well-being, and social relationships in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010:639–649. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Nyandiko W. M., Liu H., Wanzhu T., Scanlon M. L., Slaven J. E., …, Inui T. S. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children and adolescents in western Kenya. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014:19227. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Scanlon M. L., Mwangi A., Turissini M., Ayaya S. O., Tenge C., Nyandiko W. M. A cross-sectional study of disclosure of HIV status to children and adolescents in western Kenya. PLoS One. 2014:e86616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Wiehe S. E., Pearce E. C., Nyandiko W. M. A systematic review of pediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2008:686–691. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816dd325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. S., Garber J., Greene J. W. Psychosocial correlates of recurrent childhood pain: A comparison of pediatric patients with recurrent abdominal pain, organic illness, and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993:248–258. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. S., Greene J. W. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: More somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1989:231–243. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson K. D., Papageorgiou A. C., Jones G. T., Taylor S., Symmons D. P., Silman A. J., Macfarlane G. J. Low back pain in schoolchildren: The role of mechanical and psychosocial factors. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2003;(1):12–17. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L., Mellins C. A., Marhefka S., Battles H. B. Disclosure of an HIV diagnosis to children: History, current research, and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007:155–166. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267570.87564.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access—progress report 2011. Geneva: Author; 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline on HIV disclosure counselling for children up to 12 years of age. Geneva: Author; 2011b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global update on the health sector repsonse to HIV, 2014 (Vol. (WHO/HIV/2014.5)) Geneva: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]