Abstract

We evaluated the association of blood monocyte and platelet activation markers with the risk of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in a multicenter study of atherosclerosis among African American and Caucasian patients. Flow cytometric analysis of blood cells was performed in 1791 participants (209 cases with PAD and 1582 noncases) from the cross-sectional Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Carotid Magnetic Resonance Imaging ([MRI] ARIC Carotid MRI) Study to assess platelet glycoproteins IIb and IIIa, P-selectin, CD40 ligand, platelet–leukocyte aggregates, monocyte lipopolysaccharide receptor, toll-like receptors (TLRs) 2 and 4, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1, cyclooxygenase 2, and myeloperoxidase. Multivariate regression analyses evaluated the association of cellular markers with the risk of PAD. After adjusting for age, race, and gender, platelet CD40L, and monocyte myeloperoxidase (mMPO) levels were significantly lower (P < .001), and monocyte TLR-4 levels were higher (P = .03) in patients with PAD. With additional adjustments for conventional risk factors, mMPO remained inversely and independently associated with the risk of PAD (odds ratio [OR]: 0.35, P = .01).

Keywords: peripheral arterial disease, monocytes, myeloperoxidase, platelets, flow cytometry, multicenter study

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is caused by progressive atherosclerosis which occludes the arterial lumen with consequent ischemic tissue injury and severe clinical complications such as claudication and ulceration.1 Evidence from recent studies has established atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disorder.2,3 Atherosclerotic lesions are promoted by immune and inflammatory cells, notably lymphocytes and monocytes, that transmigrate into the arterial wall from circulating blood, as well as proinflammatory mediators and reactive oxygen species generated by blood and vascular cells.4 Although it is now established that leukocytes transmigrated from blood play an essential role in atherosclerosis, it remains uncertain whether blood cell function in the circulating blood is associated with atherosclerosis. Recent reports revealed a significant association of total white blood cell count with PAD and other atherosclerotic disorders.5,6 Limited data on these processes are available from population-based studies, mostly due to the complex measurement methodology. We postulated that blood platelet and monocyte activation and proinflammatory molecules are associated with the risk of PAD. To test this hypothesis, we examined the association between platelet and monocyte activation and proinflammatory markers, and cell aggregates, and the case status of PAD by flow cytometry using data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Carotid Magnetic Resonance Imaging (ARIC Carotid MRI) Study.

Material and Methods

Study Population

The ARIC study is a multicenter, cohort study of atherosclerosis among African American and Caucasian men and women from 4 US communities.7 The baseline examination was conducted from 1986 to 1989, and cohort members were reexamined triannually over 9 years. The ARIC Carotid MRI study, which consisted of 2066 participants enrolled in 2005–2006 from the ARIC cohort, was designed to further improve our understanding of cellular factors and their association with atheromatous plaques.8 Ankle and brachial systolic blood pressures were measured bilaterally using a standardized protocol. Pheripheral arterial disease was defined by a presence of reduced ankle–brachial blood pressure index (ABI) lower than 0.9. For this investigation, 1791 participants were available for analysis after excluding those with missing measures, resulting in 209 cases with PAD and 1582 noncases.

Flow Cytometry Measurements

We used whole blood flow cytometry (Coulter Epics XL, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Miami, FL) to measure platelet and monocyte antigen levels and platelet–leukocyte aggregates.9 Blood samples were collected in Cyto-Chex BCT vacutainer tubes (Streck, Omaha, Nebraska) containing EDTA and a cell membrane stabilizer for blood cells.10 They were shipped to the central laboratory by overnight courier, and samples were analyzed immediately after arrival. We measured the following markers: platelet CD41 (glycoprotein [GP]-IIb), CD61 (GP-IIIa), CD62P (P-selectin), and CD154 (CD40L); monocyte CD14 (lipopolysaccharide [LPS] receptor), CD162 (P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 or PSGL-1), toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2; CD242), TLR-4 (CD244), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), myeloperoxidase (MPO), leukocyte CD45, and cell aggregates including platelet–monocyte, platelet–lymphocyte, and platelet–neutrophil aggregates (PMA, PLA, and PNA, respectively). Data are presented as proportion of cells expressing the antigen (%) and/or the relative level of antigen expression assessed by median fluorescent intensity (MFI). For cells expressing more than 90% of the antigen, only the MFI is reported.

Statistical Analysis

For all analyses, data were weighted by the inverse to reflect the population estimates using SAS callable SUDAAN software, version 9.0.1 (RTI, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) to account for the complex survey design of the ARIC Carotid MRI Study. Bivariate relationships were explored by comparing simple or adjusted means or proportions between groups using the REGRESS procedure for continuous variables and the RLOGIST procedure for categorical variables (SUDAAN, Research Triangle Institute (RTI), Research Triangle Park, NC). Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess independent associations of cellular markers with PAD status after adjustments for age, race, and gender (model 1), or additionally adjusted for diabetes, waist-to-hip ratio, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), C-reactive protein (CRP), smoking status, hypertension, and lipid-lowering medication use (model 2). Odds ratios (OR) for PAD were estimated by contrasting the highest versus the lowest tertile of cellular markers. For race-specific analyses, the entire sample was used to obtain unbiased standard error estimates in each of the race subgroups.

Results

Comparison of Platelet and Monocyte Markers Between Cases With PAD and Noncases

Of the 2066 ARIC cohort members who participated in the Carotid MRI Study, 275 were excluded from the present analysis because data were missing on PAD (n = 192) or cellular markers (n = 83). Of the 1791 remaining, 209 (11.7%) were classified as patients with PAD. Table 1 shows the demographic and cardiovascular risk factor characteristics by the case status of PAD. Consistent with previous reports, a number of conventional risk factors such as age, race, current smoking, body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, blood pressure, and CRP levels were positively associated, while HDL cholesterol and alcohol intake were negatively associated with PAD. A higher proportion of cases with PAD versus noncases were hypertensive, diabetic, current smokers, or took lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications. Plasma levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were not significantly associated with PAD. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was lower in cases with PAD compared with noncases (P = .011).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the ARIC Carotid MRI Study Sample by the Case Status of PADa

| Characteristic | PAD Cases (n = 209) | PAD Noncases (n = 1582) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73.0 (5.8) | 69.8 (5.4) | <.001 |

| Race (black), % | 48 | 19 | <.001 |

| Sex (female), % | 59 | 55 | .43 |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 30.4 (5.5) | 28.9 (5.3) | .01 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.96 (0.1) | 0.94 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 191 (42) | 195 (41) | .31 |

| Lipid lowering medication use, % | 55 | 39 | .001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 113 (38) | 114 (36) | .90 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 47 (12) | 50 (15) | .01 |

| Log CRP, mg/L | 1.00 (1.1) | 0.73 (1.0) | .01 |

| Ethanol intake, g/week | 25 (64) | 38 (88) | .03 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130 (20) | 125 (18) | .01 |

| Hypertensive, % | 85 | 62 | <.001 |

| Antihypertensive use, % | 60 | 42 | <.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 41 | 22 | <.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 19 | 7 | <.001 |

| Former smoker, % | 48 | 41 | .11 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 79 (27) | 81 (23) | .01 |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Presented are demographic and cardiovascular risk factor characteristics by the case status of PAD and the statistical significance of their association with PAD. Values are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

When the mean MPO values were analyzed by level of renal disease as determined by eGFR (normal, mild, moderate, severe) using standard cut points there appeared to be clear linear relationship between MPO and renal function (Table 2). The test of linear relationship across GFR level (decreasing MPO with increasing renal dysfunction) is P = .002.

Table 2.

Myeloperoxidase Values, Mean (SD) by Level of Renal Disease Determined by eGFRa

| eGFR | N | MPO (MFI) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal: ≥90 | 507 | 94.6 (26.8) |

| Mild: 60–90 | 946 | 92.3 (24.3) |

| Moderate: 30–60 | 283 | 87.3 (23.6) |

| Severe: <30 | 12 | 84.8 (19.5) |

Abbreviations: eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate, ml/min per 1.73 m2; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MFI, median fluorescent intensity.

The test of linear relationship across GFR level (decreasing MPO with increasing renal dysfunction) is P = .002.

A selective list of platelet and monocyte markers assessed by flow cytometry is shown in Table 3 by the case status PAD. Relative to noncases, participants with PAD had significantly higher MFI values for platelet CD61 and significantly lower values for platelet CD40L. Among the leukocyte markers, lymphocyte PSGL-1 values were higher in cases with PAD, while monocyte TLR-2 and MPO were lower in cases with PAD versus noncases. There were no significant differences in cell aggregates between cases with PAD and noncases. As shown in Table 4, MFI values for platelet CD40L and monocyte MPO (mMPO) remained significantly lower and percentages of monocyte TLR-4 higher in cases with PAD than noncases after adjustment for age, race, and gender. With additional adjustment for conventional risk factors, the association of platelet CD40L and PAD was attenuated and borderline nonsignificant (P = .06), while the mMPO associations remained significant. CD61 was no longer significantly associated with PAD in the adjusted models.

Table 3.

| Flow Cytometry Parameter | PAD Cases (n = 209) | PAD Noncases (n = 1582) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets | |||

| CD41, MFI | 80.5 (13.9) | 78.9 (12.3) | .22 |

| CD61, MFI | 65.1 (18.4) | 60.9 (17.8) | .01 |

| CD62P, % | 28.5 (15.3) | 28.5 (14.0) | .98 |

| CD62P, MFI | 23.0 (8.0) | 21.8 (5.6) | .58 |

| CD40L, % | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.9 (2.5) | .99 |

| CD40L, MFI | 12.2 (1.1) | 12.5 (1.8) | <.001 |

| Leukocytesc | |||

| CD14, MFI | 112.1 (22.4) | 111.8 (20.8) | .86 |

| TLR-2, % | 60.6 (12.2) | 62.6 (11.7) | .07 |

| TLR-2, MFI | 13.8 (1.2) | 14.0 (1.4) | .04 |

| TLR-4, % | 65.5 (4.0) | 65.0 (4.1) | .17 |

| TLR-4, MFI | 16.5 (1.0) | 16.4 (1.0) | .43 |

| PSGL-1, MFI | 114.6 (16.2) | 111.9 (15.2) | .07 |

| lPSGL-1, MFI | 56.8 (11.3) | 53.2 (10.6) | <.001 |

| COX-2, % | 98.1 (2.5) | 98.1 (3.6) | .97 |

| COX-2, MFI | 17.0 (2.9) | 17.4 (2.8) | .13 |

| CD45, MFI | 75.4 (12.4) | 75.0 (9.8) | .76 |

| lCD45, MFI | 195.7 (24.7) | 198.0 (26.1) | .37 |

| MPO, MFI | 85.8 (27.2) | 92.8 (24.8) | <.01 |

| Cell aggregates | |||

| PMA, % | 17.6 (4.2) | 17.6 (4.3) | .99 |

| PLA, % | 17.0 (4.1) | 16.9 (4.2) | .73 |

| PNA, % | 16.9 (4.2) | 16.9 (4.2) | .90 |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MFI, median fluorescent intensity; TLR, toll-like receptor; PSGL, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand; COX, cyclooxygenase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PMA, platelet–monocyte aggregate; PLA, platelet–lymphocyte aggregate; PNA, platelet–neutrophil aggregate.

The ARIC Carotid MRI Study.

Presented are measures of platelet and monocyte markers assayed by flow cytometry in cases with PAD and noncases and the statistical significance of their association with the case status of PAD.

Results are for monocytes unless labeled differently (l = lymphocytes)

Table 4.

| Flow Cytometry Parameter | PAD Cases (n = 209) | PAD Noncases (n = 1582) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets | ||||

| CD40L, MFI | Model 1d | 12.2 (0.09) | 12.5 (0.06) | .003 |

| Model 2e | 12.3 (0.10) | 12.5 (0.06) | .06 | |

| Monocytes | ||||

| TLR-4, % | Model 1 | 65.8 (0.38) | 65.0 (0.13) | .03 |

| Model 2 | 65.7 (0.39) | 65.0 (0.13) | .08 | |

| MPO, MFI | Model 1 | 82.6 (2.31) | 93.1 (0.74) | <.001 |

| Model 2 | 83.8 (2.37) | 93.0 (0.75) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; MFI, median fluorescent intensity; TLR, toll-like receptor; MPO, myeloperoxidase; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Parameters with significant (P < .05) difference in age, race, and gender-adjusted means.

The ARIC Carotid MRI Study.

Presented are flow cytometry measures of platelet and monocyte markers in PAD cases and non-cases analyzed by 2 statistical models:

Model 1: adjusted for age, race, and gender.

Model 2: also adjusted for diabetes, waist-to-hip ratio, TC, HDL, CRP, smoking status, hypertension, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Odds Ratios of PAD by mMPO Tertiles

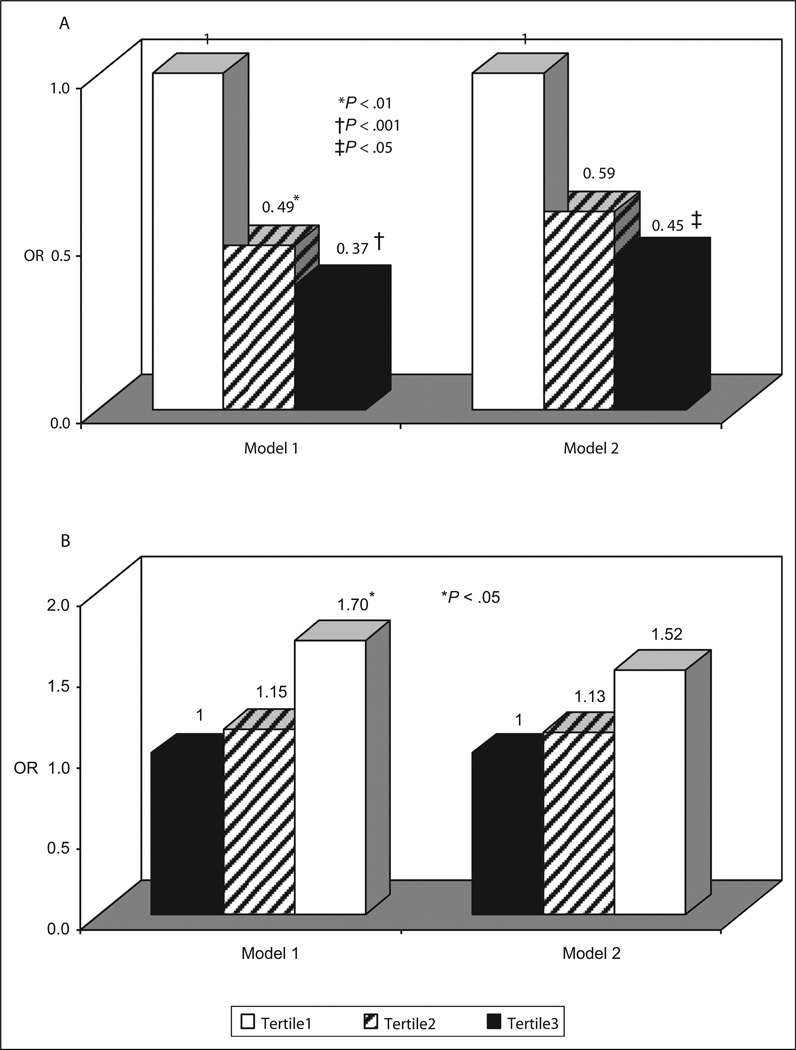

A major finding from analysis was the significant inverse association of mMPO with PAD case status. We further explored the associations by comparing the odds of PAD across tertiles of mMPO. Examining risk factors prevalence across the mMPO tertiles showed that age and prevalence of cigarette smoking declined as mMPO tertiles increased, while BMI and LDL-cholesterol were positively associated with mMPO tertiles (data not shown). Individuals in the middle and upper tertiles of mMPO were at lower risk of PAD than were individuals in the lowest tertile (Figure 1A). After adjustment for demographic variables and risk factors (model 2), the OR for PAD comparing the highest to the lowest tertile of mMPO was 0.45 (P = .002). Race-specific results given in Table 5 suggest that the negative association of mMPO tertile with PAD risk may be stronger in whites than blacks. After adjusting for age, race, gender, and other risk factors, the ORs for PAD comparing the highest to the lowest tertile of mMPO was 0.35 (P = .01), while the comparable ORs among blacks was 0.55 (P = .08). We further explored the associations between monocyte TLR-4 and PAD case status by comparing the odds of PAD across tertiles of monocyte TLR-4 (%). After adjustment for age, race, and gender, higher TLR-4 tertile was associated with increased risk of PAD with an OR of 1.70 for the highest versus the lowest tertile (P = .03; Figure 1B, model 1). After further adjustment for risk factors, the association of TLR-4 with PAD was attenuated and no longer significant (OR = 1.52, P = .06) (Figure 1B, model 2). Race-specific analyses showed that the association between monocyte TLR-4 and risk of PAD was stronger in whites than blacks (OR for comparison of highest vs lowest tertile: 1.98 vs 1.38 [model 1] or 1.69 vs 1.31 [model 2]).

Figure 1.

A, Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of PAD by tertile of monocyte myeloperoxidase (mMPO, MFI). Tertile 1 (white bars): 6.1–79.9; tertile 2 (shaded bars): 79.9–100; tertile 3 (black bars): 100–209.1. B, Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of PAD by tertile of monocyte TLR-4 (%). Tertile 1 (white bars): 49.3–63.4; tertile 2 (shaded bars): 63.4–66.7; tertile 3 (black bars): 66.7–95.0. Model 1: Adjusted for age, race, and gender. Model 2: Also adjusted for diabetes, waist-to-hip ratio, TC, HDL, CRP, smoking status, hypertension and lipid-lowering medication use. PAD indicates peripheral arterial disease; MFI, median fluorescent intensity; TLR, toll-like receptor; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Table 5.

| Whites (n = 1340) | Blacks (n = 451) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1c | Model2d | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| OR | P Value | OR | P Value | OR | P Value | OR | P Value | |

| MPO | ||||||||

| Upper vs lower | 0.26 | <.001 | 0.35 | .01 | 0.48 | .03 | 0.55 | .08 |

| Middle vs lower | 0.51 | .04 | 0.61 | .13 | 0.50 | .06 | 0.57 | .14 |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; MPO, myeloperoxidase; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

The ARIC Carotid MRI Study.

Presented are the associations of monocyte MPO with PAD status in whites and blacks using 2 statistical models:

Model 1: adjusted for age, race, and gender.

Model 2: also adjusted for diabetes, waist-to-hip ratio, TC, HDL, CRP, smoking status, hypertension, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between various cell markers expressed by circulating blood platelets and monocytes and PAD in participants of the ARIC Carotid MRI study. A major finding was that monocyte enzyme MPO is inversely and independently associated with risk of PAD. Monocytic intracellular MPO levels were significantly lower in PAD cases vs noncases, and the ORs for PAD of mMPO in the upper tertile were significantly reduced (~0.5) compared to those in the lower tertile. The inverse relationship between mMPO content and prevalence of PAD in our study may be explained by release and depletion of mMPO during monocyte activation.11 This possible explanation is supported by reports that plasma MPO levels are increased in patients with coronary heart disease and are associated with increased risk of major cardiac events.12,13 This notion is further strengthened by reports that humans with MPO deficiency or reduced MPO expression have reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases.14 Interestingly, Zhang et al12 found a positive association of leukocyte MPO content and coronary artery disease, while our study reports an inverse association of the intracellular mMPO and PAD. The reasons for this are not clear, but many differences between the 2 studies probably contributed to it. Namely, Zhang et al used multiple steps and procedures to isolate neutrophils from whole blood by centrifugation, which were then subjected to cell lyses, freezing, thawing, and then to an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) which uses polyclonal antibody to MPO. The MPO was expressed per milligram of total cell proteins. In our study, monocytes were analyzed directly in whole blood, without centrifugation steps which are known to contribute to loss of some cells, and mMPO was expressed as the median MPO content per single cell. Monocyte MPO was quantified by a direct immunostaining with a specific monoclonal antibody raised against purified human MPO and directly conjugated to FITC; it has been optimized to recognize the human intracellular MPO in whole blood samples. It is likely that the 2 antibodies (a polyclonal used in ELISA and monoclonal in our flow cytometry) recognize different epitopes at the MPO molecule.

Macrophage MPO has been detected in human atherosclerotic lesions and considered to play an important role in tissue inflammation and injury.15 It was recently reported that MPO-positive neutrophils accumulate in mice with atherosclerotic lesions.16 However, MPO data from murine experiments should be interpreted with caution as differences between human and murine MPO expression in leukocytes exist.17 Myeloperoxidase is a member of the heme peroxidase superfamily. It constitutes about 5% of human neutrophil protein and catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to hypochlorous acid (HOCl). Upon activation, neutrophils secrete large quantities of MPO which produces HOCl that reacts with plasma constituents such as LDL, HDL, and endothelial cells to promote atherosclerosis and other forms of vascular diseases. The MPO content in circulating monocytes is lower than that in neutrophils and has been reported to constitute about 1% of monocyte proteins.18 Our results suggest that MPO in human monocytes is about 10% of that in neutrophils (data not shown). Prior results on the association of neutrophil MPO content with PAD are controversial. Brevetti et al19 reported a reduced neutrophil MPO content in patients with coronary artery disease having PAD compared to those without PAD. Monaco et al20 evaluated inflammatory and prothrombotic markers in hospitalized patients with unstable angina (UA) and PAD and found neutrophil activation, as assessed by its intracellular content of myeloperoxidase (using a different methodology), was only observed in UA but not in patients with PAD, suggesting that atheroma burden is less related to neutrophil MPO content than systemic inflammation in UA. In the study by Buffon et al11 intra-leukocyte MPO staining using a hematologic analyzer was assessed in participants with stable and unstable coronary artery disease sampled at both the coronary artery and the cardiac vein, allowing for evaluation of a “transcoronary inflammation gradient” across inflamed vascular bed in unstable. These studies supported widespread activation of neutrophils across the coronary vascular bed in patients with UA, indicating that patients with more “vulnerable plaque” show greater reduction in leukocyte MPO content.

To our best knowledge, the association of mMPO content with PAD has not been previously reported. The flow cytometry assay allows for measuring intracellular MPO content in individual cells independent of the total white blood cell count which is a major factor affecting measurements of serum MPO levels. Our data thus provide novel information concerning the role of mMPO in PAD. Whether these markers relate to incident adverse events is an important question. The ARIC will eventually try to address this question but currently the sample size, and therefore the number of incident adverse events is too low, to address it yet.

It is well recognized that monocytes play a key role in atherogenesis. They transmigrate the endothelium to enter the vascular wall where they mediate inflammation and generate foam cells. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study reported that monocytes are the only leukocyte subtype significantly associated with PAD.21 A previous report suggested the proinflammatory potential of monocytes in an in vitro model was higher in patients with PAD than in controls.22 Our data provide a more direct evidence for an association of circulating blood monocyte activation with PAD risk.

Blood monocyte activation may be triggered by diverse agents such as LPS, other microbial products, as well as CD40 ligand and P-selectin. Stimulating agents activate monocytes by interacting with specific receptors on the monocyte surface. We analyzed the association with PAD of monocyte TLR-4 and CD14, receptors for LPS; TLR-2, receptor for other bacterial products; and PSGL-1, receptors for P-selectin. We also included platelet P-selectin, ligand of PSGL-1 and platelet CD40L, and ligand ofCD40 in this association study. After adjustment for age, gender, and race, monocyte TLR-4 was significantly associated with PAD risk. However, the association became insignificant after additional adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, suggesting that association is explained by confounding factors.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TLR-4 expression is upregulated in human atherosclerotic plaques and in animal models.23,24 Furthermore, TLR-4 together with CD14 polymorphisms synergistically influences atherosclerosis in patients with PAD.25 Thus, circulating monocyte TLR-4 is an important player not only in atherosclerotic progression but also in atherogenesis.

Platelet activation results in secretion of CD40L and P-selectin. CD40L interacts with CD40 on monocytes and transmits signals to activate monocytes and has been shown to play an important role in atherosclerosis.26,27 P-selectin mediates leukocyte transmigration into the vessel wall and interacts with PSGL-1 to activate monocyte. Furthermore, P-selectin is involved in platelet aggregate formation. Analysis by flow cytometry in this study showed that cases with PAD had significantly lower levels of CD40L than noncases although after adjustments for traditional risk factors it had borderline significance (P = .06). Platelet CD40L correlated with P-selectin, and both activation markers showed an inverse correlation with the percentage of single, nonactivated platelets (r = −.30 and −.27, respectively), indicating increased platelet activation. On the other hand, it is possible that lower platelet CD40L expression in PAD may be attributed to its engagement to platelet–leukocyte aggregate formation (through CD40-CD40L interactions).

In our study, platelet–leukocyte complexes were not associated with PAD. Several studies reported platelet hyper-reactivity and elevation, while others reported lower platelet P-selectin in patients with PAD compared to controls.28–30 The differences may be explained by differences in patient selection and study design.

Interestingly, when data were analyzed by ethnic origin, and after adjusting for traditional risk factors, the magnitude of the association between mMPO and PAD risk was stronger in whites than blacks. This observation deserves further investigation because PAD is less prevalent in Caucasians than African Americans.31 It also may be due to the relatively small sample size for African Americans.

This study has potential limitations. The cross-sectional design allows us to estimate the associations reported herein but not to establish cause and effect relations. Thus, based on biologic and mechanistic plausibility, our results suggest a pathogenic role of selected cellular markers but do not establish their antecedent role. Similarly, since genetic and environmental variations modulate MPO expression, we cannot exclude the effect of either source of variability, nor apportion the role of either, in the observed mMPO levels. Genetic studies are underway in the ARIC Carotid MRI participants. A drawback of our study is that we did not collect data to distinguish whether participants with low ABI were symptomatic or not. Since they were outpatients who could come to an examination center and were detected as having PAD by ABI screening, we presume most were asymptomatic. Monaco and others19,20 have suggested that unstable vascular disease results in the depletion of leukocyte MPO content. Therefore, our pooling for this study of symptomatic (presumably unstable) and nonsymptomatic patients with low ABI may have diluted the observed association of mMPO with PAD. A final limitation is that we only had a single measurement of cellular markers and although most of the measurements have good reliability,8 measurement error would tend to weaken observed association.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that monocyte activation is associated with PAD and suggest that they play roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis as indexed by PAD. Our results also provide strong support for a role of MPO as a PAD risk factor, particularly in Caucasians.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. We thank Dr. Diane Catellier for providing additional statistical analysis. In addition, thanks are extended to Dr R Michelle Sauer for editorial support.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC- 55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC-55019, N01-HC- 55020, N01-HC-55021, and N01-HC-55022 with the ARIC carotid MRI examination funded by U01HL075572-01.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkind MS, Cheng J, Boden-Albala B, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Elevated white blood cell count and carotid plaque thickness: the northern Manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 2001;32(4):842–849. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CD, Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, Chambless LE, Shahar E, Wolfe DA. White blood cell count and incidence of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke and mortality from cardiovascular disease in African-American and White men and women: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(8):758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.8.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folsom AR, Aleksic N, Sanhueza A, Boerwinkle E. Risk factor correlates of platelet and leukocyte markers assessed by flow cytometry in a population-based sample. Atherosclerosis. 2008;205(1):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catellier DJ, Aleksic N, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Carotid MRI Flow Cytometry study of monocyte and platelet markers: intraindividual variability and reliability. Clin Chem. 2008;54(8):1363–1371. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warrino DE, DeGennaro LJ, Hanson M, Swindells S, Pirruccello SJ, Ryan WL. Stabilization of white blood cells and immunologic markers for extended analysis using flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2005;305(2):107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buffon A, Biasucci LM, Liuzzo G, D’Onofrio G, Crea F, Maseri A. Widespread coronary inflammation in unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(1):5–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, et al. Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2136–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldus S, Heeschen C, Meinertz T, et al. CAPTURE Investigators. Myeloperoxidase serum levels predict risk in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2003;108(12):1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000090690.67322.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutter D, Devaquet P, Vanderstocken G, Paulus JM, Marchal V, Gothot A. Consequences of total and subtotal myeloperoxidase deficiency: risk or benefit? Acta Haematol. 2000;104(1):10–15. doi: 10.1159/000041062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama S, Okada Y, Sukhova GK, Virmani R, Heinecke JW, Libby P. Macrophage myeloperoxidase regulation by granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in human atherosclerosis and implications in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Pathol. 2001;158(3):879–891. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Leeuwen M, Gijbels MJ, Duijvestijn A, et al. Accumulation of myeloperoxidase-positive neutrophils in atherosclerotic lesions in LDLR−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(1):84–89. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.154807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholls SJ, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(6):1102–1111. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000163262.83456.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos A, Wever R, Roos D. Characterization and quantification of the peroxidase in human monocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;525(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(78)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brevetti G, Schiano V, Laurenzano E, et al. Myeloperoxidase, but not C-reactive protein, predicts cardiovascular risk in peripheral arterial disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(2):224–230. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monaco C, Rossi E, Milazzo D, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation in unstable angina is largely unrelated to the atherothrombotic burden. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasir K, Guallar E, Navas-Acien A, Criqui MH, Lima JA. Relationship of monocyte count and peripheral arterial disease: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(9):1966–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000175296.02550.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luu NT, Madden J, Calder PC, et al. Comparison of the pro-inflammatory potential of monocytes from healthy adults and those with peripheral arterial disease using an in vitro culture model. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(2):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edfeldt K, Swedenborg J, Hansson GK, Yan ZQ. Expression of toll-like receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions: a possible pathway for plaque activation. Circulation. 2002;105(10):1158–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullick AE, Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Modulation of atherosclerosis in mice by Toll-like receptor 2. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3149–3156. doi: 10.1172/JCI25482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vainas T, Stassen FR, Bruggeman CA, et al. Synergistic effect of Toll-like receptor 4 and CD14 polymorphisms on the total atherosclerosis burden in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(2):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young RS, Naseem KM, Pasupathy S, Ahilathirunayagam S, Chaparala RP, Homer-Vanniasinkam S. Platelet membrane CD154 and sCD154 in progressive peripheral arterial disease: a pilot study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190(2):452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blann AD, Tan KT, Tayebjee MH, Davagnanam I, Moss M, Lip GY. Soluble CD40L in peripheral artery disease. Relationship with disease severity, platelet markers and the effects of angioplasty. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(3):578–583. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajagopalan S, Mckay I, Ford I, Bachoo P, Greaves M, Brittenden J. Platelet activation increases with the severity of peripheral arterial disease: implications for clinical management. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(3):485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robless PA, Okonko D, Lintott P, Mansfield AO, Mikhailidis DP, Stansby GP. Increased platelet aggregation and activation in peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25(1):16–22. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBane RD, 2nd, Karnicki K, Miller RS, Owen WG. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on circulating platelets. Thromb Res. 2004;113(2):137. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kullo IJ, Bailey KR, Kardia SL, Mosley TH, Jr, Boerwinkle E, Turner ST. Ethnic differences in peripheral arterial disease in the NHLBI Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. Vasc Med. 2003;8(4):237–242. doi: 10.1191/1358863x03vm511oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]