Abstract

From the first day of imprisonment, prisoners are exposed to and expose other prisoners to various communicable diseases, many of which are vaccine-preventable. The risk of acquiring these diseases during the prison sentence exceeds that of the general population. This excess risk may be explained by various causes; some due to the structural and logistical problems of prisons and others to habitual or acquired behaviors during imprisonment. Prison is, for many inmates, an opportunity to access health care, and is therefore an ideal opportunity to update adult vaccination schedules. The traditional idea that prisons are intended to ensure public safety should be complemented by the contribution they can make in improving community health, providing a more comprehensive vision of safety that includes public health.

Keywords: communicable diseases, disease prevention, health promotion, prisons, vaccination

Abbreviations

- HIPP

Health in Prisons Program

- WHO

World Health Organization

- IDU

injecting drug users

- LGBT

lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HAV

hepatitis A virus

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HTLV

human T-lymphotropic virus

- MSM

men who have sex with men

Introduction

In any prison there is usually a conflict between the objectives of safety and security, control of the prison population and public health goals. Since 1995, the Health in Prisons Program (HIPP) of the World Health Organization (WHO) has attempted to lead and guide this broad discussion between prison safety and global health, using a perspective derived from the experiences and recommendations applied in the European region. This review aims to broaden and deepen this debate, proposing and arguing why vaccination strategies should be the spearhead of the health system within the prison system.

Prisons and Health,1 a recent HIPP publication, suggests various aspects that should be considered to improve the physical and mental health of prisoners and reduce the risks of imprisonment for health and the society using a comprehensive human-rights based approach. This approach, like others, presents some inconsistencies and may not be effective in the daily health care provided to prisoners, especially with respect to the control of vaccine-preventable diseases and recommendations on vaccination schedules.2

After water purification, vaccination is probably the intervention that has most helped to improve human life expectancy.3 Vaccination is a very efficacious and cost-effective intervention, as it may eliminate and even eradicate some infectious diseases. For these reasons, of all the potential health interventions in prisons, those related to vaccine-preventable diseases should be a priority. Access of prisoners to vaccination has a direct impact not only on the target population, but also the wider community.

In general, vaccine administration criteria are based on age (routine vaccination schedule) and specific risk, either individual or group (e.g., specific vaccines for people with chronic illness, vaccines for health workers). The high coverages achieved by routine vaccination result in herd immunity, which can reduce or even halt the transmission of some contagious diseases. Some specific vaccination strategies go further, requiring an active search for individuals or groups that are difficult to access and represent pockets of people at high risk for vaccine-preventable diseases or their complications. These directed interventions can significantly improve vaccination coverages compared with traditional vaccination strategies. Prisons, with a population detained in a confined space, provide a paradigmatic opportunity for vaccination interventions.4

In addition to an accessible population, prisons present an opportunity to achieve enormous benefits using a good vaccination program, mainly because this population is at higher risk of contracting diseases than the rest of the population.2 The many determinants of this increased risk of acquiring infectious diseases in prisons (with a corresponding impact on the community) include overpopulation and overcrowding, high levels of social vulnerability and prison lifestyles, the prevalence of communicable diseases and the rotational dynamics of the prison population.

There are surprisingly few thorough reports on this topic globally, and operational research on vaccination programs and coverages in prisons is limited.5 A possible explanation is that prisons were designed and structured solely to ensure public safety. This, possibly limited, idea of safety, which persists today, works against the concept that prisons could offer real opportunities to access health care and play an important role in a global, integrated strategy for reducing the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases, both inside and outside prisons. This perspective positively extends the concept of safety.

Importance of vaccination in prisons

From the perspective of vaccinology, prisons should be considered a public health priority for 4 main reasons (Table 1):

Table 1.

Importance of vaccination in prisons

| Access to vulnerable social groups |

|---|

| Groups with little normal access to the health system |

| Prisoners come from disadvantaged social strata (educational and socioeconomic level) |

| Greater history of illicit drug use before entering prison |

| Greater history of alcohol abuse |

| High prevalence of carriers of communicable diseases and other morbidities |

| Overrepresentation of especially-vulnerable groups: LGTB, sex workers, immigrants |

| Progressively greater proportion of elderly adults |

| High risk of acquiring infections in prison |

| Sexual activity, often unprotected, in prisons |

| High rate of starting or returning to illicit drug use (injectable and non-injectable) |

| Tattoos / piercings |

| Physical violence (injuries, rapes) |

| Permanent contact with the community |

| High rotation rates in prison (short sentences, transfers) |

| Visits/ staff/ temporary release |

| High risk of extreme behavior in the first weeks after release (drug abuse) |

| Prison population is known and concentrated in one place |

| Population identified and easily located |

LGBT: gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual.

Access to vulnerable social groups

The prison population is mainly composed of young men from the most disadvantaged social classes and educational levels. Marginal populations are often overrepresented in prison populations.6 Most prisoners make little use of national health services when at liberty.6-8 Today's global mobility has increased the number of foreign prisoners. Immigrants, depending on their origin, may have different health needs from the autochthonous population, including the need for vaccination. In Spain, for example, the foreign population is 9.7% of the total, but it nevertheless represents about a third of the prison population.9 Other minorities in prison, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) persons are particularly vulnerable groups.1 Most female prisoners are of childbearing age and 3–5% are in the gestation period, and therefore require specific care.10,11

As in the general population, the proportion of prisoners aged ≥65 y is progressively increasing and, in some cases, the increase is even higher inside than outside prison.12 The aging process is accelerated in prison, i.e., chronic diseases and disabilities develop between 10–15 y earlier than in the rest of the population.1,13 As a result, some criminal justice systems consider the equivalent to the medical cutoff of 65 y to be 55 or even 50 y in prisoners,14,15 with the corresponding implications for vaccination policies, such as influenza vaccination.

Reports on injecting drug users (IDU) before prison admission show a high use (5% to 38%) compared with the general population.16 Proportionally, 3 times as many prisoners smoke compared with the general population,17 and prisoners have a higher rate of alcohol abuse.18 A study from the US showed that prisoners had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction and asthma than age- and sex-matched people outside prison.19,20 The prevalence of female prisoners with abnormal cervical cytology is much higher than in the general population.11,21 Deaths from lung cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and liver cancer are more common in inmates compared to the general population.22,23

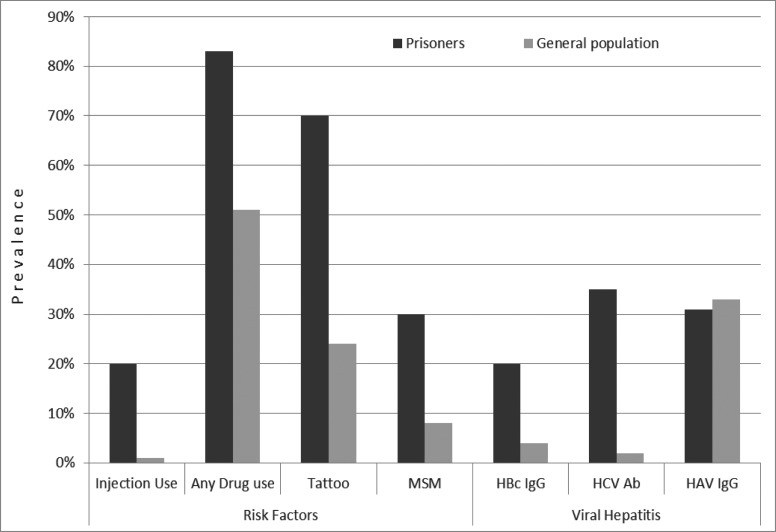

Unsurprisingly, rates of tuberculosis in prisons may exceed rates in the community by 5 to 70 times.2,24,25 US studies suggest that 25% of HIV-infected individuals26,27 and 40% of chronic carriers of viral hepatitis have been incarcerated.27 Studies show the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in prisoners is more than 10 times higher than that of the general population.28-33 The prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is between 1.8 and 62%, and is higher than that of the general reference population in all studies (Fig. 1).30,31,34-42

Figure 1.

Comparison of US estimates of lifetime prevalence (%) of viral hepatitis risk factors and seroprevalence of hepatitis A, B and C virus exposure in inmates vs. the overall population 2009. HBc IgG, IgG antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; HCV Ab, antibody to hepatitis C Total virus. HAV IgG, IgG antibody to hepatitis A. MSM, men who have sex with men. Figure modified from “Viral hepatitis in incarcerated adults: a medical and public health concern;” by Hunt, DR & Saab S.44

These clinical and social factors describe a population that could benefit from various vaccination strategies: prisoners whose lifestyle before imprisonment makes them more susceptible to acquiring vaccine-preventable diseases with potentially severe complications and even death.

Prisoners are at high risk of vaccine-preventable diseases during imprisonment

It is estimated that approximately 30% of prisoners are sexually active in prison, and most will not use methods that minimize the risk of the sexual transmission of diseases.43,44 Surveys in Welsh prisons show 14% of prisoners were men who have sex with men (MSM) and, of these, 20% had sex with men only during their period of incarceration.45 In addition, a considerable proportion of sex in prison is non-consensual and, therefore, violent. US studies have shown a rate of rape of 3–5% in male prisoners.46 The true figures are probably higher, and in some groups, such as LGBT, the rates are up to 10 times greater.1,47 It is also estimated that the prevalence of physical violence, not necessarily sexual, is much greater in prisoners.1,48

Tattooing and piercing are prevalent in prisons and are closely linked to prison sub-cultures: 53% of UK prisoners have a tattoo, of which the tattooing occurred in prison in 11%. Due to the scarcity of sterile equipment, inadequate instruments, with an increased risk of disease transmission (guitar strings, clips, nails), are often used.49-51 According to studies analyzing self-reported attitudes, the prevalence of illicit drug use in prisons varies between 22 and 48% worldwide, and IDU is between 6 and 26%, with 25% of IDU being initiated in prison.40,52-54

The structural and logistical instability of many prisons worldwide, an increasingly precautionary penal system with progressive overpopulation and overcrowding, poor ventilation in cells, the lack of sanitation and hygiene, poor food quality, limited availability of health care, etc.,55 are additional risk factors for greater transmission of vaccine-preventable diseases. In addition, these conditions often violate fundamental human rights.1

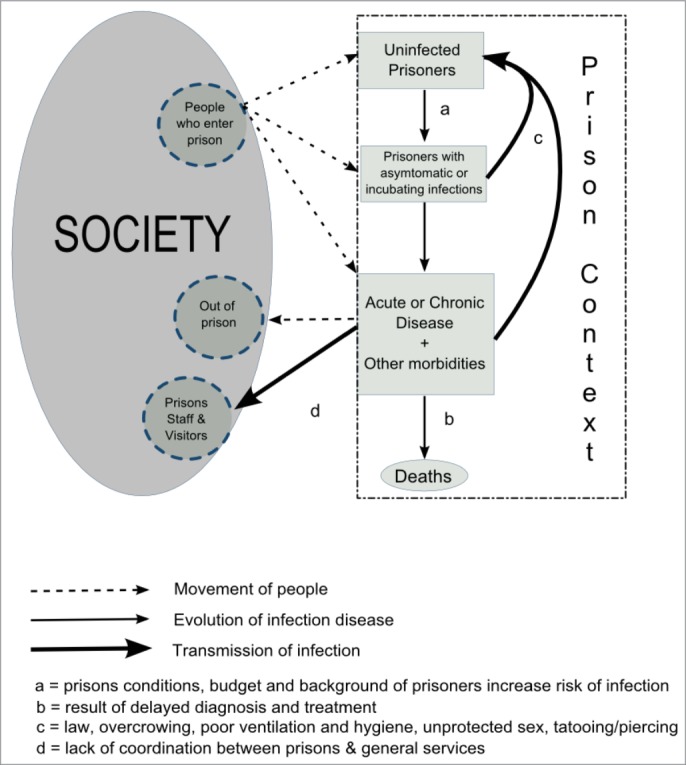

Of the high incidence of new cases of vaccine-preventable diseases in prison, a significant fraction should be considered attributable to the persistence of endemic diseases or the development of epidemics in the community.24 (Fig. 2) .

Figure 2.

Transmission of communicable diseases inside and beyond prisons. Figure modified from Guidelines for the Control of Tuberculosis in Prisons, WHO 1998.153

Prisoners are in constant contact with the rest of the community

Although prisons are closed institutions, inmates are in frequent contact with the community. Prison staff, visitation rights, day leave and other “privileges” allow inmates access to the rest of the community, with which it interacts. In addition, many sentences are relatively short and almost all the prison population will, at some point, be reintegrated into society. The annual flow or rotation of prisoners can be 5 times higher than the total permanent prison population,56,57 which is an indirect indicator of the close interaction between prisoners and the rest of society. Moreover, the highest frequency of risk behaviors such as drug abuse are reported in the first 3–4 weeks after release.58

Prisoners are accessible and susceptible to vaccination

Theoretically, prisoners' access to vaccination should be simple. Prisoners are an identified, recorded, defined and easily-accessible population and this should ensure high vaccination coverages with satisfactory health outcomes in prisons.4,59

Biological risks in prison and recommended vaccines

Despite regional epidemiological characteristics (e.g., higher seroprevalence of HTLV I/II or Trypanosoma cruzi in Brazilian prisons,60 and a higher prevalence of intestinal parasites in Ethiopian prisoners61) most of the biological risks to which prisoners and prison staff are exposed are quite similar throughout the world (Table 2). In the following paragraphs, we describe evidence on vaccination and current recommendations for prisons, accompanied by an epidemiological overview of disease inside and outside prison (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Strategies and Recommended Guidelines

| Vaccine | Recommendations/Strategies | Schedules | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B | All new inmates with negative or unknown serology. | Normal: 0, 1 and 6 months Accelerated: 0, 1, 2 and 12 m Rapidly-accelerated: 0, 7, 21 d and 12 m | Previous serology recommended. |

| New inmates with risk factors: IDUs, chronic disease, MSM, mental illness. | |||

| Hepatitis A | All new inmates with negative or unknown serology. | HA: 0 – 6 months HAV/HAVB: 0, 1, 2 and 12m HAV/HBV: 0, 7, 21 and 12 m | Evaluate age and place of origin. |

| New inmates with risk factors: IDUs (pre-serology not necessary), MSM and hepatic risk factors. | |||

| Tetanus/diphtheria | Prisoners without demonstrated history of vaccination. | 0, 1 and 6–12 months (Td) | Evaluate vaccination if there are lesions. |

| All new inmates with last dose > 10 y ago. | 1 booster dose (Td) | ||

| PCV13* and PPSV23** | Prisoners aged more than 65 y* | 0 (PCV13) and 6–12 months (PPSV23). If previous PPSV23, PCV13 > = 1 y* | Two doses of VP23 recommended in specific risk groups** |

| Prisoners aged more than 18 y with baseline pathology included in recommendations** | 0 (PCV13), PPSV23 minimum of 8 weeks later** | ||

| Seasonal influenza | All new inmates | One annual dose during influenza season. | |

| Risk groups: > 65 years, pregnancy, chronic medical condition or immunosuppression | |||

| Mumps, measles and rubella | All new inmates with negative or unknown serology. | History of childhood vaccination: 1 dose. No history of vaccination: 0, 1 month. | |

| Women of child-bearing age. | |||

| Human papilloma virus | Women with no history of vaccination or incomplete vaccination. | 0, 1–2 and 6 months | Prioritize persons aged less than 26 y Upper limits vary by country*** |

| Meningococcal C | Inmates aged less than 26 y | 1 doses | |

| Varicella | Prisoners with proven history of vaccination. | 0–4,8 weeks | |

| Prisoners who remember receiving one dose. | One booster dose |

IDUs: injecting drug users. MSM: Men who have sex with men. HAV: Hepatitis A virus. HBV: Hepatitis B virus. PCV13: 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. PPSV23: 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

CDC 2014 recommendations.102

See risk groups: CDC 2012.103

WHO 2014: recommends an upper age limit of age of 26 y.122

Table 2.

Biological Hazards Prison

| Transmisson by serum | |

| HIV | |

| Hepatitis B* | |

| Hepatitis C | |

| Respiratory transmission | |

| Tuberculosis* | |

| Influenza* | |

| Measles* | |

| Mumps* | |

| Rubella* | |

| Meningococcal infection* | |

| Pneumococcal infection* | |

| Enteric transmission | |

| Hepatitis A* | |

| Transmission by contact | |

| Herpes simplex | |

| Varicela Zoster* | |

| Scabies | |

| Viral conjuntivitis | |

| HPV* | |

| Diphtheria* | |

| Tetanus* | |

Vaccine available.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Hepatitis B in prison

| Country (reference) | City, State or Region | Survey year | Prisons | Population | Seroprevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia (35) | New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia | 2004, 2007, 2010 | 29 | 1388 914(IDUs) | 2.3% 3.1%(IDUs) |

| Brazil (68) | Goias (State) | 2007–08 | 1 | 150 | 0.7% – 1.3% |

| Brazil (69) | Sao Pablo (State) | 2003 | 1 | 333 | 2.4% – 1.2% |

| Croatia (65) | All country | 2005–2007 | 20 | 3290 | 1.3% |

| England and Wales (66) | Different regions | 1997 – 98 | 8 | 3930 775 (IDUs) | 8% 20%(IDUs) |

| Ghana (70) | Different regions | 2004–05 | 8 | 1366 | 25.5% |

| Hungary (41) | All country | 2007–09 | 20 | 4894 | 1.5% |

| Iran (64) | Isfahan | 2009 | 2 | 970 (IDUs) | 3,3% (IDUs) 13,9% (IDUs) |

| Mexico (67) | West central Mexico | 2007 | 1 | 30 | 20% |

| Nigeria (71) | Nasarawa (State) | 2007 | 4 | 300 | 23% |

| Pakistan (34) | Karachi | 2007–08 | 1 | 357 | 5.9% |

| Spain (31) | All country | 2008 | 18 | 342 | 2.6% |

| USA (42) | Different States | Studies between 1975 and 2005 | 25 | nd / meta-analysis 23 studies | 0,9% – 8% 6,5% – 42% |

EEUU: United States of America. IDUs: prevalence among injecting drug users. HbsAg=hepatitis B surface antigen; HBc IgG=IgG antibody to hepatitis B core antigen.

* = hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg).

** = IgG antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (HBc IgG).

*** = HbsAg plus HBc IgG positives. nd = no data.

Hepatitis B

Currently, 240 million people worldwide suffer from chronic hepatitis B,62 which caused 786,000 deaths worldwide in 2010. The prevalences documented in prisons are always higher than in the general reference population,19,63 with IDUs having the highest risk. Data on the prevalence of HBsAg vary by region (Table 3).31,34,35,42,64-71 Whether due to the progressive introduction of routine vaccination of younger cohorts or to the longer exposure time, the disease prevalence is usually greater in older adults.40

Although HBV vaccination has been recommended since 1982 in prisons, the proportion of susceptible individuals is still higher than is acceptable and, in countries like France and the US, barriers to the correct implementation of recommendations have only been overcome in the last decade.72,73 In middle-and low-income countries, HBV vaccination is far from routine. It has been shown that, for every dollar invested in HBV vaccination, $2.13 is saved in later treatment and care costs.74 Current recommendations may vary and should be adapted to the capabilities of the prison; ideally, all new prisoners who are not immune or whose serology is unknown should be vaccinated.1,75 HBV serology testing is recommended since the identification of chronic carriers is another determining factor in controlling the disease. If all prisoners cannot be vaccinated, priority should be given to those with known risk factors, such as IDUs, prisoners with chronic diseases, and risk populations such as immigrants or indigenous people, among others. The rapid (0, 1 and 2 m) and extra-rapid (0, 7 and 21 days) schedules facilitate adherence and compliance, and have been shown to provide optimal seroprotection.76,77

Hepatitis A

According to global estimates, there were 126 million acute cases of hepatitis A, and 35,245 deaths in 2005.78,79 Few outbreaks have been described in prisons, although outbreaks are increasing in IDUs and MSM.52,80-85 In Italy, Rapicetta et al81 observed a prevalence of HAV antibodies in 86.4% of prisoners, which was higher in foreign prisoners (92.1%), of whom none reported being vaccinated. In the US, the reported prevalence of past HAV infection was 22% to 39%, comparable to the general population.86,87 The prevalence of HAV antibodies in Luxemburg was 57.1% and 65.9% in IDUs versus non-IDUs, respectively.85

HAV vaccination is recommended for all new prisoners with an unknown immune status and those who are unvaccinated.1,2 Previous serology testing is less important because HAV infection is a self-limiting disease without chronic carriers. If all susceptible prisoners cannot be vaccinated, they should be prioritized according to age, origin and risk factors (IDUs, MSM and hepatic risk factors).87,88 For HAV vaccination alone, the recommended schedule is 0 and 6 months, although the accelerated (0, 1, 2 m) and rapidly-accelerated (0, 7, 21 and 1 year) HAV/HBV schedules have also been used.89,90 If accelerated schedules are used, it is important to administrate as many doses as possible, as one dose of HAV vaccine (> 90% of immunogenicity) alone gives more protection than one dose of the combined HAV/HAB vaccine. The administration of combined schedules is also more complex.86,91

Tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis

Globally, the 1989 WHO neonatal tetanus elimination program resulted in a reduction in new cases of 92% by 2008.92 A total of 4,680 (2013) cases and 2,500 deaths due to C. diphtheria were reported in 2011.93 A total of 136,000 cases of pertussis were reported in 2013, and 89,000 deaths were reported in 2008.94 There is little data on the coverage of the combined vaccine in prisons. A seroprevalence study in a Canadian prison found 49% of inmates were incompletely vaccinated.95

The recommendations are similar to those for the general population: people in whom prior vaccination cannot be proven should be vaccinated at 0, 1 and 6–12 months, and people not vaccinated for 10 y should receive a booster dose.75,96

Pneumococcal disease

In 2005, 1.6 million people died from pneumococcal disease.97 The prevalence in prisons is unknown and few outbreaks have been reported.98,99 Despite this lack of data, the high burden of non-communicable diseases − of which chronic lung disease is one of the most frequent − is an important risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD).1,100 The risk of IDP in some prisoners, such as those infected with HIV or splenectomized is about 100 times higher than in healthy prisoners, and therefore pneumococcal vaccination should be routine in prisons.101 The current recommendation is that prisoners aged ≥ 65 y and those with risk factors should be vaccinated.1,75 The recent availability of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in adults is an option that provides more-efficient protection.102,103

Seasonal influenza

Global estimates suggest annual seasonal influenza epidemics result in approximately 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and 250,000 to 500,000 deaths. Many seasonal influenza outbreaks have been reported in prisons.104-109 James et al.110 studied influenza outbreaks in 43 closed institutions (8 prisons) in the last 120 y in the UK, and found an attack rate of 3% to 69%. Seasonal influenza vaccination in prisons has long been rejected, although it has often been used for secondary prevention in the event of outbreaks.111,112 The influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in 2009 may have acted as an important stimulus for organizations like the CDC and the UK Health Protection Agency to introduce vaccination for primary prevention in prisons, as coverages in US prisons were <50% in 2009.113

All prisoners and staff should receive the seasonal influenza vaccine before the virus becomes active in the community, instead of just vaccinating people aged >65 y.1,2

Mumps, measles and rubella

The disease burden of these 3 diseases is higher in children, although it is more severe in adults.114 Larney et al. studied the susceptibility of new prisoners in 7 Australian prisons; 41% were susceptible to mumps, 16% to rubella, 13% to measles and 10% to varicella, similar to the general population.37 In Switzerland, susceptibility to mumps was low (6%) in immigrant prisoners.115 In a Canadian correctional facility, 2% of young people were susceptible to one of the 3 viruses.95

Outbreaks have been described in prisons,116,117 but have declined significantly since the introduction of routine vaccination. Susceptibility studies in prisoners provide similar results to those of the general population, and there is limited knowledge of the history of vaccination in prisoners who have suffered these diseases. These records are critical because true herd immunity requires high coverages (95% for mumps).118 The ideal recommendation would be to vaccinate all new prisoners who are susceptible or whose immune status is unknown.1,75 If selective vaccination is the option chosen, women of childbearing age, the country of origin and age according to the dates of routine introduction of the vaccine in different countries could serve to select priorities. The regimen is 2 doses at 0 and 1 months. If childhood vaccination without information on the current immune status is reported, one dose of vaccine should be administered.75

Human papillomavirus

Globally, in 2010, the estimated prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in women with normal cytological findings, was 11.7%, with a peak in women aged < 25 y (21.7%).119 The prevalence of HPV in males is less homogenous, varying from 49.4% (HIV-) and 78.2% (HIV + 78.2%) in sub-Saharan Africa120 to 1% to 84% in the EU and 2% to 93% in the US in groups at low and high risk of HPV, respectively.121,122 A study of 190 female prisoners in the Amazon region of Brazil found a prevalence of 10.5%.123 In Taiwan, the prevalence in 150 female prisoners was 55.4% (47.4% in HIV- and 63.9% in HIV + ).124 In Mexico, the prevalence was 20.7% in 82 prisoners.125 In Spain, a prevalence of HPV of between 27.4% and 46% of female prisoners was recorded.126,127 These prevalences are higher than in the general population of the respective countries.

Since its approval, the HPV vaccine has been used in some juvenile detention centers in the UK and USA.128,129 Henderson et al.128 described its use in US prisons, and found that lack of knowledge about the vaccine and the short period in prison were the main barriers to successful vaccination. New female prisoners are at high risk for HPV and cervical cancer,130 and vaccination should be initiated or completed, although the recommended upper age limits for vaccination vary between countries. Prioritization of immunocompromised subjects may be appropriate. For male prisoners, vaccination is not a priority,122 but MSM and immunocompromised subjects should receive special attention.131 The normal schedule of 0, 1–2 and 6 months is recommended.

Meningococcal meningitis

There is no reliable estimate of the global disease burden. The greatest age-adjusted incidence rate is found in the African meningitis belt.132 Of the 12 serogroups identified, 6 can cause outbreaks (A, B, C, W, X and Y), and these have a very-specific geographical distribution. Some outbreaks have been reported in prisons.133-135 In the UK, one dose of meningococcal C conjugate vaccine is administered to prisoners aged <25 years,75 identical to the policy in the general population.

Varicella

The global disease burden is about 4.2 million severe complications and 4,200 deaths annually.136 There is a high risk of transmission and outbreaks in prisons,2,75 even when the percentage of susceptible inmates is low. In an outbreak in a California prison, 2% of exposed prisoners were susceptible.137 In Switzerland, 12.7% of prisoners were susceptible, with immigrants having a risk nearly 6-fold greater than the general population.138 In an Italian prison, the susceptibility was 14.5%.139 In a global seroprevalence study in an Australian prison, 10% of prisoners were susceptible.37

There are few recommendations on the use of the varicella vaccine in prisons: some indicate serological screening and vaccination of all non-immune prisoners, in order to reduce the potential risk of outbreaks.2,140 General vaccination is also recommended for new prisoners if an outbreak is suspected.141

Tuberculosis

The overall prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) in 2013 was 159 cases per 100,000 population, with an incidence of 126/100,000 and a mortality of 16/100,000.142 More than one million incident cases had HIV. In some countries, the incidence in prisons is up to 100-fold that of the general population.143 A systematic review by Baussano et al.24 estimated a mean annual incidence in prisons of 237.6 (interquartile range (IQR): 156–639) cases per 100,000 people and 1,942 (IQR: 1,045–2,778) per 100,000 in high and medium-low income countries, respectively. In a WHO literature review, prisons from Russia (4,560 per 100,000) and Georgia (5,995 per 100,000) had the highest prevalence rates, followed by some African countries.144 The BCG vaccine is currently only recommended in children born in countries with a high disease burden and medical personnel in close contact with cases of TB, especially multi-resistant bacilli.145 The vaccine is not indicated in specific prevention programs in prisons due to its lack of efficacy in preventing TB in adults.1,146

Concluding remarks

The vast majority of epidemiological data on vaccine-preventable diseases and the use of vaccines in prisons comes from studies in high-income countries, where prison health programs are more developed and recommendations take into account the particularities of the respective population. Prison conditions in medium-low income countries are generally worse, the risk for vaccine-preventable diseases is much higher, and the scarcity of resources makes the application of new vaccines, such as conjugate vaccines, which are usually more expensive, more difficult. The prison population and the proportion of elderly persons within it are increasing worldwide, pushing up global incarceration costs. The case of the US is the prototype of this problem; the American penal system costs more than 74 billion dollars per year, eclipsing the GDP of more than 130 countries.147 Addressing these high costs with a model of healthy prison initiatives such as vaccination − although this would involve further investment − would generate indirect savings for the health system and have a positive impact on overall welfare. However, there are few available studies on the cost-effectiveness of vaccination in prisons and the performance of their health systems. No study has evaluated the introduction of an integrated prison vaccination program. This is an important research gap that could potentially aid decision making. Most studies focus on a single vaccine, mainly hepatitis B vaccine.74,91,115 Jacobs et al.91 examined the cost effectiveness of substituting bivalent hepatitis A/B for the hepatitis B vaccine in US prison inmates, and state rates of hepatitis A. In states with high rates of hepatitis A (200% the national average) introduction of hepatitis A/B vaccination would prevent 466 hepatitis A infections, 60 hospitalizations, 1.6 premature deaths, and the loss of 28 life-years ($ 22,819 per life-year saved). In states with lower rates (100–200 and <100%) the cost-effectiveness would be $ < 0 and $ 2,131 per life-year saved, respectively. This could help reduce morbidity and mortality, therefore reducing costs. A study in a Swiss prison calculated the reduction in costs due to measles vaccination in accordance with origin and age. It was estimated that 35 % of inmates were susceptible to measles and required vaccination. This approach achieved a reduction of 62% in vaccinations in 3,000 prisoners yearly, resulting in annual cost savings of € 72, 000. The high cost of potential outbreaks was an important issue also taken into account.115 Likewise, there are few studies of the situation of female, elderly or mentally-ill inmates. In the context of prisons, it is imperative to agree on whether vaccination strategies should lower the age cut-off for considering a patient as “older” from the normal 65 y to 50 or 55 years, and to integrate current vaccination recommendations to this effect in the specific case of prisoners (Table 5).

Table 5.

Research gaps: improving the introduction of prison vaccination programs

| 1 | Cost-effectiveness assessments of integrated vaccine program introduction |

| 2 | Health technology assessment of prison vaccine program introduction |

| Promotion of reports on prison vaccination with a focus on developing countries | |

| 4 | Promotion of studies on the implementation of vaccination in female prisons |

| 5 | Gender studies on vaccination in prisons |

| 6 | Research on elderly prisoners and the impact of vaccines in this group |

| 7 | Research on the impact of vaccines on mentally-ill inmates |

The complexity of the prison context in countries or regions makes it impossible to make general “one-size-fits-all” recommendations. The first major step recommended is that the prison system delegates the responsibility and authority for prisoner's health care to the health system, because this is part of public health.148,149 This would guarantee the right to primary health care for every prisoner: in many cases this might be a first contact with the health system. Providing healthcare access to prisoners helps reduce inequalities outside prison and facilitates reintegration. Vaccines should be the spearhead of a comprehensive approach based on primary care. First, updating of the vaccination of healthy adults should be ensured (Table 6). Secondly, access to other vaccines according to individual risk should also be ensured. Thirdly, vaccines should be offered according to agreed criteria based on local epidemiological data and the availability of funds. Prison staff should receive the same treatment. Thereafter, it is essential to evaluate the quality of the strategies introduced. In the UK, one indicator of the quality of care in prisons is that 80% of prisoners should be vaccinated against hepatitis B during the first 3 months of imprisonment.150 It is debatable whether offering vaccination immediately upon imprisonment is the best strategy, since the psychological burden felt by new inmates might not provide the optimum frame of mind, could be an obstacle to compliance with the recommended immunization schedule, and might lead to rejection of the first dose or result in incomplete vaccination. Prisoners may be less likely to reject vaccination if this is offered within an integrated health care policy. Therefore, ideally, vaccination of prisoners should not be automatic, but should be integrated into an approach that shows respect for people and their rights. Moreover, refusal to vaccinate may be due to misinformation, poor knowledge of the vaccine, and fear of needles or adverse reactions. Peer educators can play a vital role in educating other prisoners about vaccine acceptance. Peers may be the only people who can speak candidly to other prisoners about ways to reduce the risk of contracting infections. Peer-led education has been shown to be beneficial for peer educators themselves: individuals who participate as peer educators report significant improvements in self-esteem.6 However, as with other educational programs, preventive education between peers is difficult when prisoners have no means to adopt the changes that would lead to healthier choices. Peer support groups need to be adequately funded and supported by staff and prison authorities, and have the trust of their peers, which can be difficult when the prison system appoints prisoners as peer educators because it trusts them, rather than because the prisoners trust them. However, the main reported barrier to achieving complete vaccination schedules remains the high turnover and dynamics of prisoners.151,152 The full integration of the prison health system should strengthen infection control in prisons and facilitate monitoring of vaccinations and other treatments after the prisoner is released.

Table 6.

Recommended steps to ensure vaccination schedules in prisons

| Integration of health services with the prison system | 1 | The authority and responsibility for health care in prison lies with the health system |

| 2 | Ensure the integration of prisons with other community health services | |

| Application of a vaccination schedule | 3 | Ensure compliance with the vaccination schedule for healthy adults |

| 4 | Ensure access to vaccination of persons with specific risk factors (HIV, HCV, MSM) | |

| 5 | Establish vaccination priorities for each prison according to identified epidemiological factors and local resources | |

| 6 | Evaluate strategies (coverage, adherence, follow up outside prison) |

Such policies would make it easier to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases in prisoners, prison staff, families and the community in general, and offer benefits to national health systems,153 as they would ensure that the prisoners would no longer be a pocket with a high burden of communicable diseases. Therefore, locally-agreed vaccination programs in prisons, based on reported evidence, are essential. Prisoners may suffer the loss of liberty but should not be punished by disease. Healthy prisons result in healthier communities, and vaccines are an essential tool in achieving this goal.

Article search criteria

We searched Medline/Pubmed for articles from the last 10 years, except for diseases where little data is available, where no time limits were set. The search terms included the MeSH terms (*correctional OR prison* OR jail*) and, for each vaccine-preventable disease of interest (infection OR infections/epidemiology OR infection OR infections/prevention and control). The references of publications located were scrutinized and relevant articles included. The gray literature, guidelines and reports of public health agencies included were identified through the Google advanced search engine. English, Spanish and Portuguese language texts were included. In the text, the term “prison” refers to all types of institution authorized by a country in which detainees are held.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

JMB has collaborated in educational activities supported by GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Novartis and Pfizer, and has participated as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur MSD. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Engginst S, Møller L, Galea G, Udensen C. Prisons and Health. Copenhagen: WHO, Regional Office for Europe; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bick JA. Infection control in jails and prisons. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45(8):1047-55; PMID:17879924; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/521910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plotkin SL, Plotkin SA. A short history of vaccination Vaccines. In Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit PA. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sequera VG, Garcia-Basteiro A, Bayas J. The role of vaccination in prisoners' health. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013; 12(5):469-71; PMID:23659294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1586/erv.13.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sequera VG, Bayas JM. Vaccination in the prison population: a review. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2012; (14):99-105; PMID:23165633; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4321/S1575-06202012000300005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moller L, Stöver H, Jürgens R, Gatherer A, Nikogosian H. Health in Prisons. A WHO guide to the essential in prison health. Copenhagen: WHO, Regional Office for Europe; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatton DC, Kleffel D, Fisher AA. Prisoners' perspectives of health problems and healthcare in a US women's jail. Women Health 2006; 44(1):119-36; PMID:17182530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1300/J013v44n01_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire J, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ. Health status, service use, and costs among veterans receiving outreach services in jail or community settings. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54(2):201-7; PMID:12556601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute of Statistics Prison population by nationality, sex and period, Spain 2014. http://www.ine.es/jaxi/tabla.do. Accesed February15, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hockings B, Young M, Falconer A, O'Rourke PK. Queensland women prisoners' health survey. Department of Corrective Service: Brisbane; 2002. https://nationalvetcontent.edu.au/alfresco/d/d/workspace/SpacesStore/c6f6a435-62d2-4c90-b052-42904ac2f5e3/701/shared/content/resources/health_women2.pdf. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bickell N, Vermund S. Human papillomavirus, gonorrhea, syphilis, and cervical dysplasia in jailed women. Am J Public Heal 1991; 81(10):1318-20; PMID:1928533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2105/AJPH.81.10.1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams B, Goodwin J. Addressing the aging crisis in US criminal justice health care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(6):1150-6; PMID:22642489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Besdine R, Boult C, Brangman S, Coleman EA, Fried LP, Gerety M, Johnson JC, Katz PR, Potter JF, Reuben DB, et al.. Caring for older Americans: the future of geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(6 Suppl):S245-56; PMID:15963180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams BA, McGuire J, Lindsay RG, Baillargeon J, Cenzer IS, Lee SJ, Kushel M. Coming home: health status and homelessness risk of older pre-release prisoners. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25(10):1038-44; PMID:20532651; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-010-1416-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baillargeon J, Black SA, Leach CT, Jenson H, Pulvino J, Bradshaw P, Murray O. The infectious disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):607-12; PMID:15066363; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Prisons and Drugs in Europe: the problem and responses. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; 2012. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/selected-issues/prison. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritter C, Stover H, Levy M, Etter JF, Elger B. Smoking in prisons: the need for effective and acceptable interventions. J Public Health Policy 2011; 32(1):32-45; PMID:21160535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1057/jphp.2010.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction 2006; 101(2):181-91; PMID:16445547; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009. Nov; 63(11):912-9; PMID:19648129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/jech.2009.090662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011; 377(9769):956-65; PMID:21093904; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorburn K. Health care in correctional facilities. West J Med 1995; 163(6):560-4; PMID:8553640 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew P, Elting L, Cooksley C, Owen S, Lin J. Cancer in an incarcerated population. Cancer 2005; 104(10):2197-204; PMID:16206295; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.21468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Guerrero J, Vera-Remartinez EJ, Planelles Ramos MV. [Causes and trends of mortality in a Spanish prison (1994-2009)]. Rev Esp Salud Publica 2011. Jun; 85(3):245-55; PMID:21892549; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S1135-57272011000300003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baussano I, Williams BG, Nunn P, Beggiato M, Fedeli U, Scano F. Tuberculosis incidence in prisons: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2010; 7(12):e1000381; PMID:21203587; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Hearlh Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/91355/1/9789241564656_eng.pdf. Accessde January11, 2015

- 26.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. Am J Public Health 2002; 92(11):1789-94; PMID:12406810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2105/AJPH.92.11.1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spaulding A, Stephenson B, Macalino G, Ruby W, Clarke JG, Flanigan TP. Human immunodeficiency virus in correctional facilities: a review. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35(3):305-12; PMID:12115097; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/341418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirwan P, Evans B, Brant L. Hepatitis C and B testing in English prisons is low but increasing. J Public Health 2011; 33(2):197-204; PMID:21345883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/pubmed/fdr011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adjei AA, Armah HB, Gbagbo F, Ampofo WK, Quaye IKE, Hesse IF, Mensah G. Correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among incarcerated Ghanaians: a national multicentre study. J Med Microbiol 2007; 56(Pt 3):391-7; PMID:17314372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1099/jmm.0.46859-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohamed HI, Saad ZM, Abd-Elreheem EM, Abd-ElGhany WM, Mohamed MS, Abd Elnaeem EA, Seedhom AE. Hepatitis C, hepatitis B and HIV infection among Egyptian prisoners: seroprevalence, risk factors and related chronic liver diseases. J Infect Public Health 2013; 6(3):186-95; PMID:23668463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saiz de la Hoya P, Marco A, García-Guerrero J, Rivera A. Hepatitis C and B prevalence in Spanish prisons. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 30(7):857-62; PMID:21274586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10096-011-1166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gough E, Kempf MC, Graham L, Manzanero M, Hook EW, Bartolucci A, Chamot E. HIV and hepatitis B and C incidence rates in US correctional populations and high risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:777; PMID:21176146; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-10-777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pomplillo MA, Pontes E, Castro A, Andrade SM, Stief AC, Martins RM, Mousquer GJ, Murat PG, Francisco RB, Pompilio S, et al.. Prevalence and epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C among prisoners of Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2011; 17(2):216-22; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S1678-91992011000200013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazi AM, Shah SA, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, Vermund SH. Risk factors and prevalence of tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among prisoners in Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14(Suppl 3):e60-6; PMID:20189863; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reekie JM, Levy MH, Richards AH, Wake CJ, Siddall DA, Beasley HM, Kumar S, Butler TG. Trends in HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C prevalence among Australian prisoners - 2004, 2007, 2010. Med J Aust 2014; 200(5):277-80; PMID:24641153; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5694/mja13.11062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramezani A, Amirmoezi R, Volk JE, Aghakhani A, Zarinfar N, McFarland W, Banifazi M, Mostafavi E, Eslamifar A, Sofian M. HCV, HBV, and HIV seroprevalence, coinfections, and related behaviors among male injection drug users in Arak, Iran. AIDS Care 2014; 26(9):1122-6; PMID:24499303; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/09540121.2014.882485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larney S, Monkley DL, Indig D, Hampton SE. A cross-sectional study of susceptibility to vaccine-preventable diseases among prison entrants in New South Wales. Med J Aust 2013; 198(7):376-9; PMID:23581958; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5694/mja12.11110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolaric B, Stajduhar D, Gajnik D, Rukavina T, Wiessing L. Seroprevalence of blood-borne infections and population sizes estimates in a population of injecting drug users in Croatia. Cent Eur J Public Health 2010; 18(2):104-9; PMID:20939261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allwright S, Bradley F, Long J, Barry J, Thornton L, Parry JV. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV and risk factors in Irish prisoners: results of a national cross sectional survey. BMJ 2000; 321(7253):78-82; PMID:10884256; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmj.321.7253.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stief AC, Martins RM, Andrade SM, Pompilio MA, Fernandes SM, Murat PG, Mousquer GJ, Teles AS, Camolez GR, Francisco RB, et al.. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among prison inmates in State of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2010; 43(5):512-5; PMID:21085860; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S0037-86822010000500008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tresó B, Barcsay E, Tarján A, Horváth G, Dencs A, Hettmann A, Csépai MM, Gyori Z, Rusvai E, Takács M. Prevalence and correlates of HCV, HVB, and HIV infection among prison inmates and staff, Hungary. J Urban Health 2012; 89(1):108-16; PMID:22143408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11524-011-9626-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harzke AJ, Goodman KJ, Mullen PD, Baillargeon J. Heterogeneity in hepatitis B virus (HBV) seroprevalence estimates from U.S. adult incarcerated opulations. Ann Epidemiol 2009; 19(9):647-50; PMID:19596205; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saum C, Surratt H, Inciardi J, Bennett R. Sex in prison: exploring the myths and realities. Prison J 1995; 75(4):413-30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/0032855595075004002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunt DR, Saab S. Viral hepatitis in incarcerated adults: a medical and public health concern. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(4):1024-31; PMID:19240708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ajg.2008.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harawa N, Sweat J. Sex and condom use in a large jail unit for men who have sex with men (MSM) and male-to-female transgenders. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010; 21(3): 1071-87; PMID:20693745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1353/hpu.0.0349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolff N, Shi J. Contextualization of physical and sexual assault in male prisons: Incidents and their aftermath. J Correct Heal Care 2009; 15(1):58-82; PMID:19477812; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1078345808326622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Struckman-Johnson C, Struckman-Johnson D. Sexual coercion reported by women in three midwestern prisons. J Sex Res 2002; 39(3):217-27; PMID:12476269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/00224490209552144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider K, Richters J, Butler T, Yap L, Richards A, Grant L, Smith AM, Donovan B. Psychological distress and experience of sexual and physical assault among Australian prisoners. Crim Behav Ment Health 2011. Dec; 21(5):333-49; PMID:21671444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hellard ME, Aitken CK, Hocking JS. Tattooing in prisons–not such a pretty picture. Am J Infect Control 2007; 35(7):477-80; PMID:17765561; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hellard ME, Hocking JS, Crofts N. The prevalence and the risk behaviours associated with the transmission of hepatitis C virus in Australian correctional facilities. Epidemiol Infect 2004; 132(3):409-15; PMID:15188710; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0950268803001882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vescio MF, Longo B, Babudieri S, Starnini G, Carbonara S, Rezza G, Monarca R. Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62(4):305-13; PMID:18339822; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/jech.2006.051599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vong S, Fiore AE, Haight DO, Li J, Borgsmiller N, Kuhnert W, Pinero F, Boaz K, Badsgard T, Mancini C, et al.. Vaccination in the county jail as a strategy to reach high risk adults during a community-based hepatitis A outbreak among methamphetamine drug users. Vaccine 2005; 23(8):1021-8; PMID:15620475; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamani S, Farnia M, Torknejad A, Alaei BA, Gholizadeh M, Kasraee F, Ono-Kihara M, Oba K, Kihara M. Patterns of drug use and HIV-related risk behaviors among incarcerated people in a prison in Iran. J Urban Health 2010; 87(4):603-16; PMID:20390391; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11524-010-9450-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fox RK, Currie SL, Evans J, Wright TL, Tobler L, Phelps B, Busch MP, Page-Shafer KA. Hepatitis C virus infection among prisoners in the California state correctional system. Clin Infect Dis United States; 2005. July; 41(2):177-86; PMID:15983913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/430913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Guerrero J, Marco A. [Overcrowding in prisons and its impact on health]. Rev Esp Sanid Penit Spain 2012. Feb; 14(3):106-13; PMID:23165634; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4321/S1575-06202012000300006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldenson J, Hennessey M. Correctional health care must be recognized as an integral part of the public health sector. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36(2 Suppl): S3-4; PMID:19131905; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318195ad6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One 2009; 4(11):e7558; PMID:19907649; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrell M, Marsden J. Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction 2008; 103(2):251-5; PMID:18199304; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bayas JM, Bruguera M, Martin V, Vidal J, Rodes J, Salleras LY. Hepatitis B vaccination in prisons: the Catalonian experience. Vaccine 1993; 11(14):1441-4; PMID:8310764; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90174-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Catalan-Soares B, Almeida RT, Carneiro-Proietti AB. Prevalence of HIV-1/2, HTLV-I/II, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi among prison inmates at. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2000; 33(1):27-30; PMID:10881115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S0037-86822000000100004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mamo H. Intestinal parasitic infections among prison inmates and tobacco farm workers in Shewa Robit, north-central Ethiopia. PLoS One 2014; 9(6):e99559; PMID:24926687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0099559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization Hepatitis B. Fact Sheet N° 204, 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 63.World Hepatitis Alliance Global Community Hepatitis Policy Report 2014. http://www.worldhepatitisalliance.org/en/civil-society-report-2014.html. Accessed January11, 2015

- 64.Dana D, Zary N, Peyman A, Behrooz A. Risk prison and hepatitis B virus infection among inmates with history of drug injection in Isfahan, Iran. Sci World J 2013; 2013: 735761; PMID:23737725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2013/735761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burek V, Horvat J, Butorac K, Mikulić R. Viral hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in Croatian prisons. Epidemiol Infect 2010; 138(11):1610-20; PMID:20202285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0950268810000476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weild AR, Gill ON, Bennett D, Livingstone SJ, Parry JV, Curran L. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C antibodies in prisoners in England and Wales: a national survey. Commun Dis Public Health 2000; 3(2):121-6; PMID:10902255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campollo O, Roman S, Panduro A, Hernandez G, Diaz-Barriga L, Balanzario MC, Cunningham JK. Non-injection drug use and hepatitis C among drug treatment clients in west central Mexico. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012; 123(1–3):269-72; PMID:22138538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barros LA, Pessoni GC, Teles SA, Souza SM, Matos MA, Martins RM, Del-Rios NH, Matos MA, Carneiro MA. Major article epidemiology of the viral hepatitis B and C in female prisoners of metropolitan regional prison complex in the State of Goiás, Central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Tro 2013; 46:24-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/0037-868216972013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coelho HC, Lourdes MD, Oliveira A, Dinis A, Passos C. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection in a brazilian jail. Rev Bras Epidemiol 2009; 12(2):124-31; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S1415-790X2009000200003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adjei AA, Armah HB, Gbagbo F, Ampofo WK, Boamah I, Adu-Gyamfi C, Asare I, Hesse IF, Mensah G. Correlates of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis infections among prison inmates and officers in Ghana: A national multicenter study. BMC Infect Dis 2008; 8:33; PMID:18328097; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-8-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adoga MP, Banwat EB, Forbi JC, Nimzing L, Christopher R, Gyar SD, Agabi YA, Agwale SM. Human immunonodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus: sero-prevalence, co-infection and risk factors among prison inmates in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries 2008; 3(7):539-47; PMID:19762972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carrieri MP, Rey D, Michel L. Universal hepatitis B virus vaccination in French prisons: breaking down the last barriers. Addiction 2010; 105(7): 1311-2; PMID:20642514; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Charuvastra A, Stein J, Schwartzapfel B, Spaulding A, Horowitz E, Macalino G, Rich JD. Hepatitis B vaccination practices in state and federal prisons. Public Health Rep 2001; 116(3):203-9; PMID:12034909; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/phr/116.3.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pisu M, Meltzer MI, Lyerla R. Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination of prison inmates. Vaccine 2002; 21(3–4):312-21; PMID:12450707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00457-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dappah E, Howes S, Perkins S. Prevention of communicable disease control in prisons and places of detention. A manual for healthcare workers and other staff. Health Protection Agency and Department of Health 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/infection-control-in-prisons-and-places-of-detention. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Asli AAZ, Moghadami M, Zamiri N, Tolide-ei HR, Heydari ST, Alavian SM, Lankarani KB. Vaccination against hepatitis B among prisoners in Iran: accelerated vs. classic vaccination. Health Policy 2011; 100(2–3):297-304; PMID:21269722; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alavian SM. Accelerated vaccination against HBV infection is an important strategy for the control of HBV infection in prisons. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2011; 44(5):652-3; PMID:22031090; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S0037-86822011000500030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization . WHO position paper on hepatitis A vaccines – June 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012. Jul 13; 87(28/29):261-76; PMID:2290536722905367 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jacobsen KH, Wiersma ST. Hepatitis A virus seroprevalence by age and world region, 1990 and 2005. Vaccine 2010. Sep 24;28(41):6653-7; PMID:20723630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ngui S, Granerod J, Jewes LA, Crowcroft NS, Teo C. Outbreaks of hepatitis A in England and Wales associated with two co-circulating hepatitis A virus strains. J Med Virol 2008; 80(7):1181-8; PMID:18461630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jmv.21207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rapicetta M, Monarca R, Kondili LA, Chionne P, Madonna E, Madeddu G, Soddu A, Candido A, Carbonara S, Mura MS, et al.. Hepatitis E virus and hepatitis A virus exposures in an apparently healthy high-risk population in Italy. Infection 2013; 41(1):69-76; PMID:23264095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s15010-012-0385-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Perrett K, Granerod J, Crowcroft N, Carlisle R. Changing epidemiology of hepatitis A: should we be doing more to vaccinate injecting drug users? Commun Dis Public Health 2003; 6(2):97-100; PMID:12889286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Franco E, Giambi C, Ialacci R, Coppola RC, Zanetti AR. Risk groups for hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine 2003; 21(19–20):2224-33; PMID:12744847; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00137-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Latimer WW, Moleko A-G, Melnikov A, Mitchell M, Severtson SG, von Thomsen S, Graham C, Alama D, Floyd L. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis A among adult drug users: the significance of incarceration and race/ethnicity. Vaccine 2007; 25(41):7125-31; PMID:17766016; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Removille N, Origer A, Couffignal S, Vaillant M, Schmit JC, Lair ML. A hepatitis A, B, C and HIV prevalence and risk factor study in ever injecting and non-injecting drug users in Luxembourg associated with HAV and HBV immunisations. BMC Public Health 2011; 11:351; PMID:21595969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-11-351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gondles EF. A call to immunize the correctional population for hepatitis A and B. Am J Med 2005; 118(Suppl 10A):84S-89S; PMID:16271547; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weinbaum C, Lyerla R, Margolis HS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2003; 52(RR-1):1-36; PMID:12562146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coffey E, Young D. Guidance for hepatitis A and B vaccination of drug users in primary care and criteria for audit. Royal College of General Practitioners 2005; p 1-6. http://www.smmgp.org.uk/download/guidance/guidance014.pdf. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Costumbrado J, Stirland A, Cox G, El-Amin AN, Miranda A, Carter A, Malek M. Implementation of a hepatitis A/B vaccination program using an accelerated schedule among high-risk inmates, Los Angeles County Jail, 2007-2010. Vaccine 2012; 30(48):6878-82; PMID:22989688; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keystone JS, Hershey JH. The underestimated risk of hepatitis A and hepatitis B: benefits of an accelerated vaccination schedule. Int J Infect Dis 2008;12(1):3-11; PMID:17643334; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jacobs RJ, Rosenthal P, Meyerhoff AS. Cost effectiveness of hepatitis A/B versus hepatitis B vaccination for US prison inmates. Vaccine 2004; 22(9–10):1241-8; PMID:15003653; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.World Health Organization Tetanus. Fact Sheets 2012. http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs_20120307_tetanus/en/. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 93.World Health Organization Diphtheria. Immunization, surveillance, assessment and monitoring 2012. http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/diphtheria/en/. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization Pertussis. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/pertussis/en/. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bartlett L, Kanellos-Sutton M, van Wylick R. Immunization rates in a Canadian juvenile corrections facility. J Adolesc Health 2008; 43(6):609-11; PMID:19027650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases second printing. Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, eds. 12th ed., Washington DC: Public Health Foundation; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 97.World Health Organization Pneumococcal disease. International travel and health 2012. http://www.who.int/ith/diseases/pneumococcal/en/. Accessed January11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mehiri-Zghal E, Decousser J-W, Mahjoubi W, Essalah L, El Marzouk N, Ghariani A, Allouch P, Slim-Saidi NL. Molecular epidemiology of a Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 1 outbreak in a Tunisian jail. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 66(2):225-7; PMID:19800751; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoge CW, Reichler MR, Dominguez EA, Bremer JC, Mastro TD, Hendricks KA, Musher DM, Elliott JA, Facklam RR, Breiman RF. An epidemic of Pneumococical disease in an overcrowded, inadequately ventilated jail. N Engl J Med 1994; 331(10):643-8; PMID:8052273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM199409083311004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet 2012; 379(9830):1975-82; PMID:22521520; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60319-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bayas J, Vilella A. Vacunas para la población penitenciaria. Rev Española Sanid Penit 2002. [cited 2014 Dec 23]; (4):39-42 [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, Gierke R, Moore MR, White CG, Hadler S, Pilishvili T, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Use of 13-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-Valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63(37): 822-5; PMID:25233284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61(40):816-9; PMID:23051612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Public Health England: Health and Justice Team Respiratory Diseases Department, Centre for Disease Surveillance and Control Guidance on responding to cases or outbreaks of seasonal flu 2014/15 in prisons and other places of detention within the criminal justice system in England. London (UK) Operational guidance 2014 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/371897/Guidance_on_seasonal_flu_2014_to_15_in_prisons.pdf. Accessed December14, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gómez-Pintado P, Moreno R, Pérez-Valenzuela A, García-Falcés JI, García M, Martínez MA, Acín E, Fernández de la Hoz K. Descripción de los tres primeros brotes de gripe A (H1N1) 2009 notificados en prisiones de España. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2010; 12(1):29-36; PMID:23128486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Turner KB, Levy MH. Prison outbreak: pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in an Australian prison. Public Health 2010; 124(2):119-21; PMID:20149400; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maruschak LM, Sabol WJ, Potter RH, Reid LC, Cramer EW. Pandemic influenza and jail facilities and populations. Am J Public Health 2009; 99(SUPPL. 2):S339-44; PMID:19797746; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Health J, Hospital W. Summer outbreak of respiratory disease in an Australian prison due to an influenza A/Fujian/411/2002(H3N2)-like virus. Epidemiol Infect 2005; 133(1):107-12; PMID:15724717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S0950268804003243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stanley L. Influenza at San Quentin Prison, California. Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 1919; 34(19):996-1008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4575142. Accessed January8, 2015; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2307/4575142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.James T, Finnie R, Hall IM, Leach S. Behaviour and control of influenza in institutions and small societies. J R Soc Med 2012; 105(2):66-73; PMID:22357982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Awofeso N, Fennell M, Waliuzzaman Z, O'Connor C, Pittam D, Boonwaat L, de Kantzow S, Rawlinson WD. Influenza outbreak in a correctional facility. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25(5):443-6; PMID:11688625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Public Health England: Health Protection Agency, Prison Infection Prevention Team Seasonal influenza outbreak at large London prison. Infection Inside 2011; 7(1). http://www.basl.org.uk/uploaded_files/infection%20inside.pdf. Accessed January5, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Receipt of A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine by prisons and jails - United States, 2009-10 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 60(51–52):1737-40; PMID:22217623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.World Health Organization Global measles and rubella strategic plan: 2012-2020. Geneva 2012. http://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/Measles_Rubella_StrategicPlan_2012_2020.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February10, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gétaz L, Rieder JP, Siegrist CA, Kramer MC, Stoll B, Humair JP, Kossovsky MP, Gaspoz JM, Wolff H. Improvement of measles immunity among migrant populations: lessons learned from a prevalence study in a Swiss prison. Swiss Med Wkly 2011; 141:w13215; PMID:21706449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nowicki D, Gajewska L, Sosada KA. Measles outbreak registered by the District Sanitary-Epidemiological Station in Częstochowa in 2013. Przegl Epidemiol 2014; 68(3):405-9, 517-20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Walkty A, Van Caeseele P, Hilderman T, Buchan S, Weiss E, Sloane M, Fatoye B. Mumps in prison: description of an outbreak in Manitoba, Canada. Can J Public Health 2011; 102(5):341-4; PMID:22032098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van Boven M, Kretzschmar M, Wallinga J, O'Neill PD, Wichmann O, Hahné S. Estimation of measles vaccine efficacy and critical vaccination coverage in a highly vaccinated population. J R Soc Interface 2010; 7(52):1537-44; PMID:20392713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rsif.2010.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(12):1789-99; PMID:21067372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/657321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Olesen TB, Munk C, Christensen J, Andersen KK, Kjaer SK. Human papillomavirus prevalence among men in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2014; 90(6):455-62; PMID:24812407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Smith JS, Gilbert PA, Melendy A, Rana RK, Pimenta JM. Age-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in males: a global review. J Adolesc Health 2011; 48(6):540-52; PMID:21575812; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.World Health Organization . Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014; 43(89):465-92; PMID:25346960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.de Aguiar SR, Villanova FE, Martins LC, dos Santos MS, Maciel Jde P, Falcão LF, Fuzii HT, Quaresma JA. Human papillomavirus: prevalence and factors associated in women prisoners population from the Eastern Brazilian Amazon. J Med Virol 2014; 86(9):1528-33; PMID:24838771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jmv.23972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chu F-Y, Lin Y-S, Cheng S-H. Human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-positive Taiwanese women incarcerated for illicit drug usage. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2013; 46(4):282-7; PMID:22841621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Canche JR, Canul J, Suárez R, de Anda R, González MR. Infección por el Virus del Papiloma Humano en mujeres recluidas en Centros de Readaptación Social en el sureste de México. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2011; 13:84-90; PMID:22071487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4321/S1575-06202011000300003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.de Sanjosé S, Valls I, Paz Cañadas M, Lloveras B, Quintana MJ, Shah KV, Bosch FX. Infección por los virus del papiloma humano y de la inmunodeficiencia humana como factores de riesgo para el cáncer de cuello uterino en mujeres reclusas. Med Clin 2000; 115(3):81-4; PMID:10965480; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0025-7753(00)71472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.González C, Canals J, Ortiz M, Muñoz L, Torres M, García-Saiz A, Del Amo J. Prevalence and determinants of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cervical cytological abnormalities in imprisoned women. Epidemiol Infect 2007; 136:215-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.National Health Service England, Public Health England, Health and Justice Team Public health services for people in prison or other places of detention, including those held in the Children &Young People's Secure Estate. London (UK) 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/383429/29_public_health_services_for_people_in_prison.pdf. Accessed January10, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 129.Henderson CE, Rich JD, Lally MA. HPV vaccination practices among juvenile justice facilities in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2010; 46(5):495-8; PMID:20413087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Binswanger IA, Mueller S, Clark CB, Cropsey KL. Risk factors for cervical cancer in criminal justice settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011; 20(12):1839-45; PMID:22004180; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/jwh.2011.2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Chesson HW, Curtis CR, Gee J, Bocchini JA Jr, Unger ER; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR-05):1-30; PMID:25167164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.World Health Organization . Meningococcal vaccines: WHO position paper, November 2011. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2011; 86(47):521-39; PMID:22128384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhang J, Zhou HJ, Xu L, Hu GC, Zhang XH, Xu SP, Liu ZY, Shao ZJ. Molecular characteristics of Neisseria meningitidis isolated during an outbreak in a jail: association with the spread and distribution of ST-4821 complex serogroup C clone in China. Biomed Environ Sci 2013; 26(5):331-7; PMID:23611126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tappero JW, Reporter R, Wenger JD, Ward BA, Reeves MW, Missbach TS, Plikaytis BD, Mascola L, Schuchat A. Meningococcal disease in Los Angeles County, California, and among men in the county jails. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:833-40; PMID:8778600; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM199609193351201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sathe PV, Mugumdar RD, Mahurkar SD, Sengupta SR. An outbreak of meningococcal meningitis in a prison (epidemiology and control). Indian J Public Health 1971; 15(3):92-6; PMID:5154305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.World Health Organization, Varicella and Herpes Zoster Vaccination Position Paper – June 2014 http://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/WHO_pp_varicella_herpes_zoster_june2014_summary.pdf Accessed January8, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 137.Leung J, Lopez AS, Tootell E, Baumrind N, Mohle-Boetani J, Leistikow B, Harriman KH, Preas CP, Cosentino G, Bialek SR, et al.. Challenges with controlling varicella in prison settings: experience of California, 2010 to 2011. J Correct Health Care 2014; 20(4):292-301; PMID:25201912; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1078345814541535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gétaz L, Siegrist CA, Stoll B, Humair JP, Scherrer Y, Franziskakis C, Sudre P, Gaspoz JM, Wolff H. Chickenpox in a Swiss prison: susceptibility, post-exposure vaccination and control measures. Scand J Infect Dis 2010; 42(11–12):936-40; PMID:20854218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/00365548.2010.511259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Valdarchi C, Farchi F, Dorrucci M, De Michetti F, Paparella C, Babudieri S, Spano A, Starnini G, Rezza G. Epidemiological investigation of a varicella outbreak in an Italian prison. Scand J Infect Dis 2008; 40(11–12):943-5; PMID:18720259; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/00365540802308449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Levy MH, Quilty S, Young LC, Hunt W, Matthews R, Robertson PW. Pox in the docks: varicella outbreak in an Australian prison system. Public Health 2003; 117(6):446-51; PMID:14522161; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00138-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Haas EJ, Dukhan L, Goldstein L, Lyandres M, Gdalevich M. Use of vaccination in a large outbreak of primary varicella in a detention setting for African immigrants. Int Health 2014; 6(3):203-7; PMID:24682723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/inthealth/ihu017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]