Abstract

Understanding space use remains a major challenge for animal ecology, with implications for species interactions, disease spread, and conservation. Behavioural type (BT) may shape the space use of individuals within animal populations. Bolder or more aggressive individuals tend to be more exploratory and disperse further. Yet, to date we have limited knowledge on how space use other than dispersal depends on BT. To address this question we studied BT-dependent space-use patterns of sleepy lizards (Tiliqua rugosa) in southern Australia. We combined high-resolution global positioning system (GPS) tracking of 72 free-ranging lizards with repeated behavioural assays, and with a survey of the spatial distributions of their food and refuge resources. Bayesian generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) showed that lizards responded to the spatial distribution of resources at the neighbourhood scale and to the intensity of space use by other conspecifics (showing apparent conspecific avoidance). BT (especially aggressiveness) affected space use by lizards and their response to ecological and social factors, in a seasonally dependent manner. Many of these effects and interactions were stronger later in the season when food became scarce and environmental conditions got tougher. For example, refuge and food availability became more important later in the season and unaggressive lizards were more responsive to these predictors. These findings highlight a commonly overlooked source of heterogeneity in animal space use and improve our mechanistic understanding of processes leading to behaviourally driven disease dynamics and social structure.

Keywords: animal personality, Bayesian generalized linear mixed models (GLMM), behavioural syndromes, global positioning system (GPS)-telemetry, movement ecology, spatial ecology

1. Introduction

Understanding what shapes spatial dynamics and animal space use is a major challenge in ecology and evolution as they link processes at the individual and population levels. Space use is critical for many, if not most, ecological processes because it determines interaction rates that individuals have with conspecifics, with other species (e.g. prey, predators, competitors, or parasites), and with key abiotic factors (e.g. heat stress). Yet, the factors shaping spatial dynamics in natural systems remain poorly understood, presumably because animal movements result from complex feedbacks between the state and traits of focal individuals and their environment [1,2]. Well-known environmental factors include the local distribution of resources and competitors [3,4], but the effects of consistent behavioural differences among individuals within a population, remain elusive [5,6]. Such differences among individuals are often referred to as behavioural types (BTs) or animal personalities and here we test how BTs interact with ecological conditions to affect animal space use.

BTs are known to influence various ecological processes [7–11]. In particular, individuals that are more exploratory, bolder, more aggressive, or more asocial than others tend to disperse more frequently and over larger distances [12–15]. Other BT-dependent aspects of space use may include home range (HR) size, relative use of patches that differ in resources or risks, and movement patterns [5,16–18], but these have received less attention. Within-species differences in space use can generate spatial and temporal variability in interactions within and among species that can, in turn, have major impacts on population and community dynamics. For example, the fact that some individuals move more widely than others or have different habitat preferences than others can have major impacts on disease spread or ecological invasions [19–21]. Our fundamental hypothesis is that individual differences in BT within a population can help to explain individual differences in space use. Although the idea of BT-dependent space use seems intuitive, its generality, temporal (e.g. seasonal) dynamics, and how it interacts with spatio-temporal variation in ecological conditions are still poorly understood. Acknowledging BT-dependent space use can also help to advance the burgeoning field of movement ecology by (partially) explaining the commonly observed intraspecific variation in movement patterns, and the deviations of individuals from theoretically expected optimal behaviours [5,6,16].

To date, empirical evidence of BT-dependent space use is particularly scarce and limited by several methodological issues. First, many studies of animal personality have used captive individuals where their space use in nature cannot be addressed. Second, many previous studies suggesting that BT affects habitat preference or space use of mammals [18,22], birds [23,24], and fish [25–28] have derived their measures of space use and BT non-independently, from the same in situ movement data. For example, activity or exploration tendency (both widely used BTs) are commonly estimated from movement data, often through dimension reduction by principal component analysis (e.g. [22,23,29]). Third, for understanding the role of social interactions (conspecific attraction or avoidance) in shaping space use, one needs to also study movements of nearby conspecifics. Thus, to more rigorously examine relationships between BT and space use, we need to track the space use of free-ranging individuals, assay their BT independently of movement, and aim to include all (or at least most) individuals in the relevant sub-population. This is feasible for strongly site-faithful, territorial species, but usually difficult for others.

We tracked free-ranging sleepy lizards (Tiliqua rugosa) and ran independent assays to determine their BTs. Simultaneously tracking most resident adults in our study site allowed us to quantify how BT-dependent responses to conspecific presence influenced individual space use. We also explored how individual BTs exhibited differential responses to ecological conditions by mapping relevant factors, such as refuge and food availability. Because their preferred food source, annual food plants, tend to dry out as summer progresses, lizards have a short activity season (spring to early summer). They occupy stable overlapping HRs with exclusive HR cores (shared only with partners) and form monogamous pair bonds, with males following females for several weeks during early spring [30]. We predicted that (i) lizards will spend more time at resource-rich sites and (ii) the importance of these ecological factors will increase with deteriorating environmental conditions as the season dries. We further predicted that (iii) BTs influence how lizards respond to the ecological predictors and (iv) the effect of lizard BT on space use will intensify as environmental conditions deteriorate. For instance, as aggressive individuals in general explore more superficially and show lower sociability [31], and aggressive male sleepy lizards have weaker social bonds and female following behaviour [30] we predicted that aggressive individuals would be less responsive to changing ecological conditions and the space use of conspecifics.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study system

Sleepy lizards are large, long-lived Australian scincid lizards with a diverse diet of mostly annual plants [32]. Adults are rarely threatened by predators [33], normally walk 100–500 m per day [34,35], and are mainly active during the austral spring (September–December), with activity ceasing by mid-summer. Pairing behaviour lasts for six to eight weeks before mating in late October [30,36,37]. The social network of sub-populations remains stable among years [38].

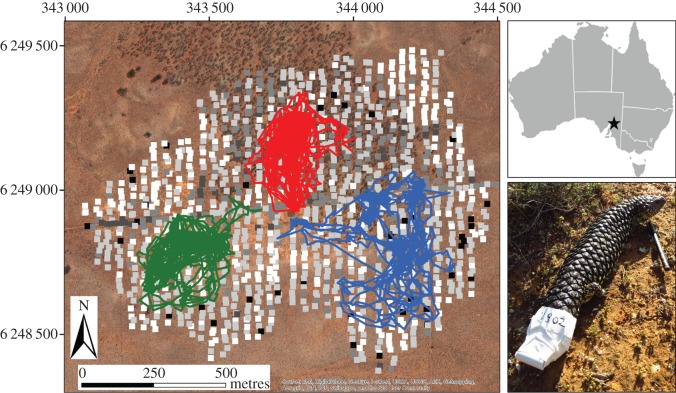

The study was conducted in a 1.2 km2 area of semi-arid chenopod shrubland near Bundey Bore Station (33°54′ S, 139°20′ E) in South Australia (figure 1). The area has cool wet winters and hot dry summers. Vegetation includes annual plants between scattered chenopod shrubs (bluebush; Maireana sedifolia) and patches of sparsely distributed black oak (Casuarina cristata). Since annual plants grow in the spring and then dry out in the summer, leaving increasingly rare patches of food plants for lizards as the season progresses, there is a strong seasonal effect within each year on available food resources [32,39]. This seasonality affects the movements and behaviour of lizards, and shaded refuges (typically large dome-shaped shrubs, fallen trees, or mammal burrows) become important later in the season as lizards seek to avoid high heat stress [39–41]. The study area has a dirt road crossing it from east to west, with two building ruins and two seasonal dams that retain water and soil moisture for longer than other parts of the area. The ruins and the roadside have more food plant resources because they are fenced to exclude livestock (but allow access to lizards).

Figure 1.

Location of the study site (black star); a GPS tagged sleepy lizard (Tiliqua rugosa); and an aerial photo of the study site with locations of ground survey quadrats in greyscale colours reflecting their refuge rank (black being the highest) and three examples of lizard tracks from the spring of 2009. Note that these particular tracks are for animals with much larger than average home ranges, chosen for ease of viewing. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Lizard tracking and behavioural assays

Tracked lizards were part of a continuous population inhabiting a similar surrounding habitat that has been studied for more than 30 years [40,42]. Tracking techniques and behavioural assays have been previously described [30,43,44]. In 2009 and 2010, at the beginning of each spring (September), we captured 60 lizards and fitted them with data loggers (43 lizards were tagged in both years). The loggers recorded GPS locations every 10 min for periods when the lizards were assessed to be active from an integrated step counter. Data were downloaded every two weeks each year until late December when lizards became largely inactive.

In 2010, we measured BTs for each lizard three times about 24 days apart, using two assays: (i) Aggressiveness was the tendency (on a scale of 1–11; least to most aggressive) for a lizard to flee or to give a threat display as an observer slowly approached to within 0.3 m (see table 1 in [30] for further details). Performance in this assay correlated with assayed responses to a lizard model and with measured scale damage [30]. (ii) Boldness was the tendency (on a scale of 1–7; shyest to boldest) for a lizard to approach and inspect an unusual food item (novel in the first trial), a banana piece placed 5 cm from its head in the presence of a potential threat from a stationary nearby observer (2 m away). Scores were repeatable (0.474 and 0.304, respectively; see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§1 for ‘adjusted repeatability’ of BT estimates while accounting for sex and trial; sensu [45]), and summed over the trials. Both assays were conducted sequentially before normal morning activity had started, and after the focal lizard had been held in an incubation chamber in situ for 40 min at 34°C. For lizards tracked in 2009, BTs were only available for the lizards also tracked in 2010.

(c). Habitat ground survey

We conducted a survey in late October to early November 2013 to assess habitat properties that may affect lizard space use. We evaluated 1 400 adjacent 20 × 20 m quadrats along 36 north–south transects (figure 1). For each quadrat, we defined a categorical habitat type: ‘Open’, chenopod shrubland; ‘Wooded’, black oak trees; ‘Mixed’, a combination of these two; and ‘Anthropogenic’, a site directly modified by humans (road, dam, or ruin). In addition, we ranked each quadrat from 1 to 5 for four ecological factors (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§2 for more details): (i) Refuge—the best available refuge in the quadrat with well-developed wombat burrows ranked highest. (ii) Cover of annuals—proportion of open-ground covered by annual plants. Mostly dry at the time of our survey. (iii) Late food—presence during the survey period of other plant food resources including berries of the ruby saltbush (Enchylaena tomentosa), live Ward's weed (Carrichtera annua), and other annuals that were still green. (iv) Abundance of Ward's weed and Compositae spp. (hereafter WW&Comp)—although these were mainly dry at the time of the survey we assumed they could indicate food availability earlier during the spring. Additionally, we measured (v) Elevation in the centre of each quadrat with a handheld Garmin GPS unit and (vi) distance to the nearest dam (hereafter DistDam). We surveyed after lizard tracking ended to ensure we included the entire area used by tagged lizards. Transects were 40 m apart (and quadrats 20 m wide), implying we collected habitat data from 50% of this area. Because local plant community structures largely reflect soil type and topography that interact to determine water runoff and soil moisture, we assumed the spatial configuration of annual plants (the major food resource) and refuges remained constant over years.

(d). Data processing and analyses

Owing to strong seasonal differences at our study site, we divided data for each year (2009, 2010) into Early (September–October) and Late seasons (November–December). During the Early season, male and female lizards are paired, the temperature is moderate, and food and water are relatively abundant. By contrast, the post-mating Late season is hotter and drier, and food and water are scarce and food is concentrated in fewer patches. Our focal response variable was space-use intensity, assessed by the number of GPS locations within each quadrat for each focal lizard during each season of each year. Quadrats that were within the minimum convex polygon HR of a lizard, but not visited by it, were scored as zero for space-use intensity. The HR centre for each lizard was defined as the centre of mass of its activity for each year. We considered how lizards responded to environmental heterogeneity at two spatial scales: a local scale, where a quadrat was scored according to the ranks for ecological factors of the quadrat itself; and a neighbourhood scale score including values from the two adjacent quadrats inversely weighted by distance from the quadrat centre (normally 20 m; see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§4 for details). GPS median horizontal accuracy of 6 m [42] prevented consideration of smaller spatial scales and larger scales were probably beyond a lizard's perceptual range [46]. We accounted for spatial autocorrelation in the data by including quadrat identity as a random factor in the statistical models. Because use intensity decreased at the HR periphery, we also included a factor of quadrat distance from the HR centre of the focal lizard (DistHRc).

We included social effects by calculating for each quadrat and lizard the relative use intensity by conspecifics (hereafter Conspcfcs). To avoid biases from unequal tracking durations or from variation in the local proportions of GPS-tagged individuals (for instance, there may be more untagged lizards using quadrats towards the site edges) we calculated Conspcfcs as follows. For each lizard, we calculated the proportional use intensity across all quadrats within its HR. Then, for each focal lizard in a quadrat we averaged this proportion over all other lizards whose HR included this quadrat. This reflects the relative usage by all tagged non-focal lizards for each quadrat. A quadrat that has been used intensively by a few tagged individuals will have a higher value than a quadrat used infrequently (or avoided) by more tagged individuals. As most quadrats were included in the HR of several lizards (mean 6.1 ± 3.9 lizards; max 21, less than 16% of quadrats were within HR of only two lizards), visitation rate by a single non-focal individual (e.g. followed sexual partner) is unlikely to bias the results.

To evaluate how space-use intensity by lizards (the dependent variable, as defined above) was influenced by all considered factors and the spatial scale (local versus neighbourhood), we used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with a Poisson distribution and log-link function. We built our models in a Bayesian framework with weakly informative priors (drawn from a normal distribution centred around zero with an s.d. = 100, thus constraining possible parameter ranges) and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) fitting techniques (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§4 for details [47]). Sixty lizards with known BTs were included as focal lizards in these models. The main predictors (or factors) included three focal lizard properties (sex, aggressiveness, and boldness) and nine quadrat properties: DistHRc, Conspcfcs, habitat type, and the six measured ecological factors (Refuge, Cover, Late food, WW&Comp, Elevation and, DistDam). Sex and habitat type were assigned dummy variable scores. All non-dummy variables were standardized around the mean. Pairwise comparison showed these factors were not strongly correlated (28 pairs, Pearson's r = 0.20 ± 0.11; max r = 0.45 between Late-food and WW&Comp).

We considered two-way interactions between the three lizard and eight quadrat properties, excluding habitat type and sex × DistHRc (due to colinearity with DistHRc as a main effect), leaving 23 interactions. For each dataset (Early, Late), we considered a set of 27 possible competing models that included individual lizards, quadrats, and years as random factors, and some or all of these predictors and their two-way interactions (see table 1 for the partial list and electronic supplementary material, table A4 for full lists of model structures). We tested our predictions by ranking models using deviance information criterion (DIC) and examined seasonal effects by modelling the two seasons separately. This approach avoided hard-to-interpret three-way interactions involving season. All statistical analyses were conducted in R [48], using the lme4 [49], Rethinking [50], and Rstan packages that compile GLMM models for evaluation in Stan computational language [51].

Table 1.

A summary comparison of the structure and ranking of GLMMs for lizards space use. Quadrat properties included its distance from HR centre (DistHRc) of the focal lizard, its usage intensity by conspecifics (Conspcfcs), its habitat type and six ecological factors (Refuge, Cover, Late-food, WW&Comp, Elevation, and DistDam). Lizard's properties included its sex and two BTs and their interactions (denoted by x) with DistHRc, Conspcfcs, and Ecological factors (abbreviated to D, C, and E, respectively). All models included random intercepts for quadrats, lizard, and lizard by year. Models were ranked using ΔDIC for Early and Late seasons and M13 (in bold) was selected as the most likely model for both datasets with a weight of 1. Models with Ecological factors assessed at the local spatial scale were almost always outperformed by their neighbourhood scale counterpart and are not presented here. Electronic supplementary material, tables A4 and A5 summarize the full model list and ranking details.

| model name | DistHRc | Conspcfcs | Hab. type | Ecol. factors | Sex | BT | interactions sexx | interactions BTx | model rank (Early) | model rank (Late) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | 16 | 16 | ||||||||

| M3 | + | 15 | 15 | |||||||

| M4 | + | + | 14 | 14 | ||||||

| M5 | + | + | + | 13 | 13 | |||||

| M6 | + | + | + | + | 12 | 10 | ||||

| M7 | + | + | + | 10 | 12 | |||||

| M8 | + | + | + | + | + | 11 | 11 | |||

| M9 | + | + | + | + | + | D, C, E | 8 | 4 | ||

| M10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | D, C, E | 7 | 5 | |

| M13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | D, C, E | D, C, E | 1 | 1 |

| M14 | + | + | + | + | + | + | D | D | 5 | 9 |

| M15 | + | + | + | + | + | + | C | C | 9 | 6 |

| M16 | + | + | + | + | + | + | E | E | 6 | 8 |

| M17 | + | + | + | + | + | + | D, C | D, C | 3 | 3 |

| M18 | + | + | + | + | + | + | D, E | D, E | 2 | 7 |

| M19 | + | + | + | + | + | + | C, E | C, E | 4 | 2 |

3. Results

We obtained tracks from 72 different lizards (50 in 2009, 60 in 2010, with 38 tracked in both years) with a total of 279 985 valid GPS locations that were contained within 1 052 of the 1 400 surveyed quadrats. For each year, individual tracks started on September 10th ± 13 days (mean ± s.d.), lasted 97 ± 21 days, and ended on December 15th ± 16 days. Each lizard used 51.9 ± 22.9 different quadrats, using about six more quadrats during the Early compared to the Late season (paired t-test: t109 = 4.1, p < 0.001). The season did not affect the number of GPS locations per quadrat (our dependent variable) or its within-individual variation. The two BTs were repeatable (electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§1) and not strongly correlated (Pearson's ρ = 0.23, p = 0.078). We found no systematic differences among BTs in the ecological properties of their HR or in the duration of their tracking (electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§3; table A2).

(a). Model comparison and main effects

We compared 27 GLMMs of lizard space-use intensity, each with 7 740 data points (table 1; see the electronic supplementary material, tables A4 and A5 for full ranking details). Models including interactions between lizard and quadrat properties outperformed other models (including those with interactions with sex but not with BTs) in both Early and Late seasons, highlighting the importance of BT-dependent space use. The best model (M13 for both seasons) included all three groups of interactions (BTs × DistHRc, BTs × Conspcfcs, and BTs × ecological factors). The second-best models included interactions between BT × ecological factors and either BT × DistHRc (M18, Early) or BT × Conspcfcs (M19, Late). The relative ranks of models with only one interaction group further corroborated that the BT × DistHRc interaction (M14) was more important than BT × Conspcfcs (M15) Early, but that their relative importance reversed later in the season. Models with ecological factors considered at the neighbourhood scale were almost always ranked higher than their local scale equivalents, implying that space use by lizards is better explained by neighbourhood characteristics than by the local environment.

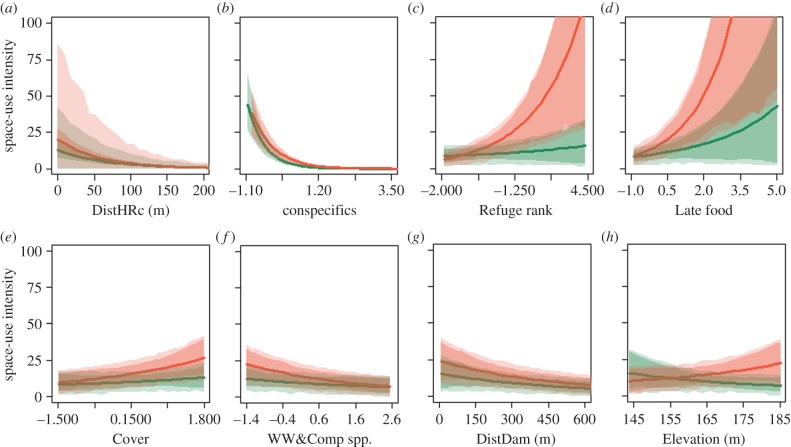

Effect sizes extracted from the best models (M13 for both seasons) are useful for comparing seasonal variation in the effect of each predictor (electronic supplementary material, figure A3), but may be misleading when comparing relative effects among predictors if those also differ in their magnitude of observed variation (e.g. Cover spans over 3.5 units of s.d. whereas Refuge ranged over 6.3 units) [50]. Hence, for each predictor, we constructed predictions across the empirically observed range of values, while using default values for all non-focal predictors (figure 2; for more information, see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§4). Both increasing distance from the HR centre and conspecific use intensity had strong negative effects on lizard's space-use intensity in both seasons (figure 2a,b; electronic supplementary material, figure A3). During the Late season, these effects were slightly stronger for DistHRc and weaker for the conspecifics, corresponding with lower conspecific avoidance. The six ecological factors all had weak, non-significant effects during the Early season (figure 2c–h; electronic supplementary material, figure A3). By contrast, during the Late season, Refuge and Late food had a strong positive effect and Cover had a weak, but significant positive effect on lizard space use (figure 2c–e). Surprisingly, in this season, lizards also used quadrats with higher WW&Comp (known food resources) less intensively (figure 2f). Lizards also used quadrats further from dams less intensively, especially in the Late season (figure 2g). The opposing effects of quadrat elevation on space use were both non-significant (figure 2h). Habitat type had almost no effect on lizard space use once these ecological factors were accounted for, with one exception—a strong enhancement in the use of the anthropogenic habitat during the Early season, where road runoff increased productivity and fencing prevents livestock grazing (electronic supplementary material, figure A3).

Figure 2.

Predicted effects of the quadrat properties included in the best models for lizard space use during the Early (dark green) and Late (light orange) seasons. (a) Distance from home range centre (DistHRc), (b) use intensity by conspecifics (Conspcfcs), (c) Refuge rank, (d) availability of Late food, (e) Cover of annuals, (f) availability of Ward's weed and Compositae spp. (WW&Comp), (g) ground Elevation above sea level, and (h) distance to the nearest dam. Solid lines are the predicted λ of the Poisson distribution for the mean lizard, and dark shaded areas are the confidence intervals for this parameter. Light shaded areas are confidence intervals for predictions while accounting for variation among lizards and years. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Interactions between behavioural types and other factors

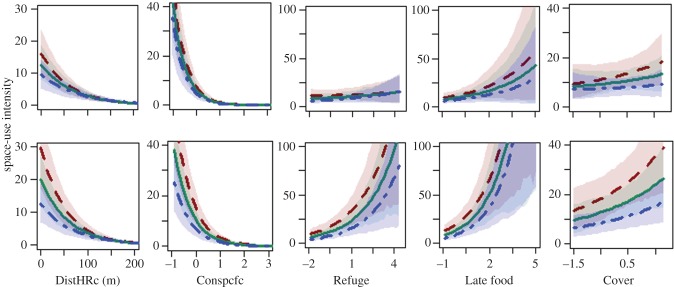

Lizards with different BTs or of different sex did not differ in their average number of GPS locations per quadrat (electronic supplementary material, figure A3). However, BT and sex affected space use through strong interactions with quadrat properties. In general, lizard aggressiveness had a stronger effect on space use (i.e. stronger interactions) than boldness or sex. Effect sizes for some of the interactions are actually larger during the Early season (electronic supplementary material, figure A4); however, generating model predictions by combining these interactions with the main effects shows that both BTs had stronger effects in the Late season (figure 3; see the electronic supplementary material, figures A5 and A6 for all interactions).

Figure 3.

Selected interactions between quadrat properties and lizards' aggressiveness during the Early (upper row) and Late (lower row) seasons. Predictors: distance from HR centre (DistHRc) and Z-scores of use intensity by conspecifics (Conspcfcs), Refuge rank, Late food availability, and Cover of annuals (see the electronic supplementary material, figure A6 for the full list). Each panel presents model predictions for non-aggressive lizards (red dashed line), the average lizard (green solid line) and aggressive lizards (blue dashed-dotted line) using the mean value for each tercile (0–33%, 33–66%, and 67–100%). The shaded areas are the confidence intervals of the predicted λ of the Poisson distribution for each tercile. Overall, aggressiveness had stronger interactions with ecological predictors during the Late season. (Online version in colour.)

Aggressiveness interacted strongly with DistHRc and Conspcfcs, and with most of the ecological factors. Interestingly, complementary analysis showed that HR size was positively associated with boldness, but only weakly with aggressiveness (electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§3, table A3). This implies that the significant interaction aggressiveness × DistHRc was driven by differential response to distance within the HR (and was not a by-product of overall HR size). Hence, while shy lizards had smaller HRs, both bold and shy lizards showed similar patterns of decreasing use of quadrats further from their HR centre. By contrast, aggressiveness did not strongly affect HR size but less aggressive lizards used quadrats closer to the HR centre more intensively than aggressive lizards. Similarly, these less aggressive lizards were overall more responsive to the different quadrat properties, whereas aggressive lizards were less likely to use quadrats used intensively by other conspecifics, or having high values of Refuge, Late food, Cover, or low values of WW&Comp. The sexes also differed in their space use mostly during the Late season, with females more responsive to Refuge rank and less to WW&Comp and distance from the dam (electronic supplementary material, figure A7).

4. Discussion

We found four main results. First, lizard space use, in general, was explained by both distance from their HR centre, and by spatial variation in ecological factors including food and refuge rankings, and the space-use intensity by other conspecifics. Second, measures of ecological factors at the neighbourhood spatial-scale explained space use by lizards better than at the local (quadrat) level. Third, this response varied between seasons with many factors having stronger influences during the Late season when environmental conditions were harsher. Finally, lizard BT (boldness and aggressiveness), assayed independently of their movement patterns, affected their space use through interactions with various quadrat properties. Models including interactions between lizard properties (BTs and sex) and distance from HR centre, conspecific space use, and ecological factors (refuge, food, and cover) were better at predicting observed space-use patterns than models without these interactions. Overall, aggressiveness had more influence than boldness and many of these interactions were more pronounced during the Late season. Below, we discuss the implications of these results.

(a). The effect of ecological and social factors on animal space use

As expected, lizards generally preferred quadrats with more food and better refuges. The preferences were clearer and stronger in the Late season. Lizards also used quadrats more if they were closer to their HR centre or had lower levels of conspecific use. This latter finding conforms with previous reports that these lizards maintain core HRs exclusive of other same sex individuals [34]. It does not conflict with males following their female partners during the Early season since pairing behaviour accounts for only 30% of their activity time [36,37]. Also, since most quadrats were visited by multiple individuals, our measure of conspecific space use is not sensitive to activity of a single conspecific. Indeed, excluding paired males (13 for 2009 and 17 for 2010) from the dataset yielded the same outcomes (electronic supplementary material, figure A8). One explanation for the negative effects of conspecific use intensity is that lizards avoid contact with some neighbouring conspecifics, a result previously reported in analyses of sleepy lizard social networks [43]. An alternative (non-mutually exclusive) explanation invokes local depletion of food resources by lizards, leading to apparent conspecific repulsion in heavily used quadrats. We cannot distinguish between those explanations because summed space use over two months does not identify social interactions, or discriminate between synchronous and asynchronous quadrat use. However, we speculate that food depletion is less plausible because lizards have an overall low density, low metabolic rates, and abundant but ephemeral food resources.

The observed seasonal differences in responses to ecological factors may reflect both internal or social factors (pairing and mating in the Early season) and external factors (drying conditions in the Late season). Teasing apart these effects would require an experimental approach. Nevertheless, many of the observed seasonal trends (e.g. stronger positive responses to Refuge rank, Late food, Cover, and distance to the nearest dam during the Late season) agree with simple expectations based on seasonally increasing heat stress and resource deterioration [41]. Resource availability at the neighbourhood spatial-scale was a consistently better predictor of lizard space use than at the local scale, implying spatial decisions are influenced by a larger scale than our single quadrats. This finding is consistent with scale-dependent foraging, where movements of animals that use patchy or spatially autocorrelated resources match intermediate spatial scales [52–54]. Lizards may obtain relevant information on resource distributions through direct detection [46] or through familiarity with their multi-year stable HR [34,55]. Future analyses can expand our binary scale comparison to a broader range of scales (e.g. [56]), and explore whether BTs differ in the spatial scales they respond to.

(b). The effect of behavioural types on animal space use

BT-dependent space use is probably very common in nature but empirical examples other than for dispersal are rare [7,11]. Our study is novel in showing that lizards with different BTs differ in their spatial response to different ecological and social factors within the same habitat. Moreover, we showed that BT-dependent responses persisted across time despite seasonal changes in internal and external conditions. Yet, these responses changed in their detail with season, highlighting the ecological complexity of BT-dependent space use. In contrast to other examples [23,25,27,57,58], the space-use differences we observed among BTs did not result from confounding factors such as using a movement-based BT definition (e.g. activity or exploration), or from any difference among BTs in the habitat or niche they occupied, or from differences in their social context (e.g. different BTs in different flock sizes).

In general, the effects of BTs on space use were more prominent during the Late season, partially because the Ecological factors they interacted with had stronger effects during this season. Aggressiveness was more important than boldness for most predictors. The observed aggressiveness × DistHRc interaction implies that (in addition to having a slightly larger HR; electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§3) aggressive individuals used their core HR less frequently (electronic supplementary material, figure A6). Accordingly, aggressive lizards were also generally less responsive to other ecological predictors (Refuge, Late food, Cover, WW&Comp, and Elevation). We consider two (non-mutually exclusive) a priori explanations for these trends. First, more aggressive lizards might invest more time in territorial behaviour such as patrolling their HR boundaries. This would explain their HR usage patterns, lower responsiveness to Conspcfcs (discussed below), and other ecological predictors. Second, as in some other species [9,11,31], more aggressive individuals may forage with more superficial exploratory behaviour, while less aggressive individuals may explore core areas more thoroughly with stronger tendency to stay longer within patches of discovered resources (using area-restricted search [48]). This will also lead to the observed stronger responsiveness of less aggressive individuals (who stay within a patch) to the ecological factors. Whether differential investment in territorial behaviour drives differential search strategies or vice versa is debatable, but together, these explanations suggest insights into alternative pathways that can result in BT-dependent space use and HR size (electronic supplementary material, appendix 1§3; see also [18,23]). In the future, more sophisticated HR indices (e.g. LoCoH or kernel analysis [59]) should be applied to test the consistency of BT-dependent response to DistHRc and HR size in different systems. Better understanding of this interaction can shed light on intraspecific variation in optimal foraging, spatial ecology and response to habitat fragmentation.

The observed BT × Conspcfcs interactions may reflect behaviour where bolder and more aggressive lizards are less responsive to conspecific activity. This conforms with the well-supported theoretical expectation that ‘proactive’ (i.e. bold, aggressive, fast-exploring) individuals tend to have lower sociability and weaker social network associations [9,31,60]. Alternatively, this pattern may reflect either BT-dependent spatial preferences (i.e. aggressive lizards prefer different, unmeasured quadrat properties, regardless of conspecifics), or stronger avoidance by other lizards of areas used by aggressive individuals. Our data cannot discriminate among these alternatives but the prevalence of interactions between BTs and DistHRc, Conspcfcs and the ecological factors in our analyses support our main argument that BT affects movement, space use and presumably also habitat preference of free-ranging animals. These effects may explain variation in the spatial distribution of BTs (e.g. why similar BTs are clumped together in some cases but not in others; [58]), in their interaction rates and overall social network positions [60].

Our study reflects a growing recognition of the importance of both animal movements and consistent intraspecific behavioural variation in understanding evolutionary and ecological processes [1,2,7,11,15]. Yet, surprisingly few studies have combined both approaches to examine the existence and consequences of BT-dependent space use. At the proximate level, links between BTs and movement patterns can be maintained by intraspecific genetic variation (e.g. in the alleles of the DrD4 or for genes) [61,62]. Alternatively, BT-dependent variation in stress hormones (in particular cortisol) can influence the perceived environmental risk and subsequent decisions by an individual with a particular BT about space use and foraging tactics [26]. Ultimately, BT-dependent space use has the potential to act as an important mechanism influencing species interactions, habitat selection, and disease dynamics, therefore affecting management-related issues such as reintroductions and BT-dependent use of protected areas and habitat corridors [7,57,60]. Further theoretical work is needed to generate additional predictions on how and why different BTs should differ in their spatial responses to spatio-temporal variation in ecological and social conditions. Future empirical work should directly explore BT-dependent movement patterns that lead to the variation in space-use patterns like those reported here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ron and Leona Clark and Chris Mosey for allowing us access to their land and the use of the homestead at Bundey Bore Station. We also thank Dale Burzacott for logistical support and Jana Bradley, Emilie Chavel, Tom Haley, Peter Majoros, and Caroline Wohlfeil for assistance with fieldwork. We are grateful for Richard McElreath and Pierre-Olivier Montiglio for their continuous statistical support and for useful feedback and for useful comments by three anonymous reviewers.

Ethics

Lizards were treated using procedures formally approved by the Flinders University Animal Welfare Committee in compliance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and conducted under permits from the South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources to Undertake Scientific Research.

Data accessibility

The data included in the paper are available through Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.h4dt0.

Authors' contributions

All authors conceived the study and participated in the fieldwork. O.S. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the writing of subsequent revisions.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Our research was funded by the Australian Research Council, the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment and NSF grant no. DEB-1456730.

References

- 1.Holyoak M, Casagrandi R, Nathan R, Revilla E, Spiegel O. 2008. Trends and missing parts in the study of movement ecology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19 060–19 065. ( 10.1073/pnas.0800483105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltz D, Smouse PE. 2008. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19 052–19 059. ( 10.1073/pnas.0800375105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens DW, Brown JS, Ydenberg RC. 2007. Foraging: behavior and ecology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartar RV, Real LA. 1997. Habitat structure and animal movement: the behaviour of Bumble bees in uniform and random spatial resource distributions. Oecologia 112, 430–434. ( 10.1007/s004420050329) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkes C. 2009. Linking movement behaviour, dispersal and population processes: is individual variation a key? J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 894–906. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01534.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson JA, Bronmark C, Hansson LA, Chapman BB. 2014. Individuality in movement: the role of personality. In Animal movement across scales (eds Hansson L-A, Akesson S), pp. 1–39. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sih A, Cote J, Evans M, Fogarty S, Pruitt JN. 2012. Ecological implications of behavioural syndromes. Ecol. Lett. 15, 278–289. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01731.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fogarty S, Cote J, Sih A. 2011. Social personality polymorphism and the spread of invasive species: a model. Am. Nat. 177, 273–287. ( 10.1086/658174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sih A, Bell AM, Johnson JC. 2004. Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 372–378. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dall SRX, Houston AI, McNamara JM. 2004. The behavioural ecology of personality: consistent individual differences from an adaptive perspective. Ecol. Lett. 7, 734–739. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00618.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf M, Weissing FJ. 2012. Animal personalities: consequences for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 452–461. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens VM, Trochet A, Blanchet S, Moulherat S, Clobert J, Baguette M. 2013. Dispersal syndromes and the use of life-histories to predict dispersal. Evol. Appl. 6, 630–642. ( 10.1111/eva.12049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn JL, Cole EF, Patrick SC, Sheldon BC. 2011. Scale and state dependence of the relationship between personality and dispersal in a great tit population. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 918–928. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01835.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Overveld T, Careau V, Adriaensen F, Matthysen E. 2014. Seasonal- and sex-specific correlations between dispersal and exploratory behaviour in the great tit. Oecologia 174, 109–120. ( 10.1007/s00442-013-2762-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cote J, Clobert J, Brodin T, Fogarty S, Sih A. 2010. Personality-dependent dispersal: characterization, ontogeny and consequences for spatially structured populations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4065–4076. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0176) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin D, Bowen W, McMillan J. 2004. Intraspecific variation in movement patterns: modeling individual behaviour in a large marine predator. Oikos 1, 15–30. ( 10.1111/j.0030-1299.1999.12730.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrete M, Tella JL. 2010. Individual consistency in flight initiation distances in burrowing owls: a new hypothesis on disturbance-induced habitat selection. Biol. Lett. 6, 167–170. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0739) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wesley RL, Cibils AF, Mulliniks JT, Pollak ER, Petersen MK, Fredrickson EL. 2012. An assessment of behavioural syndromes in rangeland-raised beef cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 139, 183–194. ( 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.04.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. 2005. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359. ( 10.1038/nature04153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dizney L, Dearing MD. 2013. The role of behavioural heterogeneity on infection patterns: implications for pathogen transmission. Anim. Behav. 86, 911–916. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.08.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cote J, Fogarty S, Weinersmith K, Brodin T, Sih A. 2010. Personality traits and dispersal tendency in the invasive mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1571–1579. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.2128) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boon A, Réale D, Boutin S. 2008. Personality, habitat use, and their consequences for survival in North American red squirrels Tamiasciurus hudsonicus. Oikos 117, 1321–1328. ( 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2008.16567.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minderman J, Reid JM, Hughes M, Denny MJH, Hogg S, Evans PGH, Whittingham MJ. 2010. Novel environment exploration and home range size in starlings Sturnus vulgaris. Behav. Ecol. 21, 1321–1329. ( 10.1093/beheco/arq151) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Overveld T, Matthysen E. 2010. Personality predicts spatial responses to food manipulations in free-ranging great tits (Parus major). Biol. Lett. 6, 187–190. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0764) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobler A, Maes G, Humblet Y, Volckaert F, Eens M. 2011. Temperament traits and microhabitat use in bullhead, Cottus perifretum: fish associated with complex habitats are less aggressive. Behaviour 148, 603–625. ( 10.1163/000579511X572035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farwell M, Fuzzen MLM, Bernier NJ, McLaughlin RL. 2014. Individual differences in foraging behavior and cortisol levels in recently emerged brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 68, 781–790. ( 10.1007/s00265-014-1691-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearish S, Hostert L, Bell AM. 2013. Behavioral type–environment correlations in the field: a study of three-spined stickleback. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 67, 765–774. ( 10.1007/s00265-013-1500-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson ADM, McLaughlin RL. 2007. Behavioural syndromes in brook charr, Salvelinus fontinalis: prey-search in the field corresponds with space use in novel laboratory situations. Anim. Behav. 74, 689–698. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.01.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kluen E, Kuhn S, Kempenaers B, Brommer JE. 2012. A simple cage test captures intrinsic differences in aspects of personality across individuals in a passerine bird. Anim. Behav. 84, 279–287. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godfrey SS, Bradley JK, Sih A, Bull CM. 2012. Lovers and fighters in sleepy lizard land: where do aggressive males fit in a social network? Anim. Behav. 83, 209–215. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.10.028) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Réale D, Garant D, Humphries MM, Bergeron P, Careau V, Montiglio P-O. 2010. Personality and the emergence of the pace-of-life syndrome concept at the population level. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 4051–4063. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubas G, Bull CM. 1991. Diet choise and food availability in the omnivorous lizard, Trachydosaurus rugosus. Wildl. Res. 18, 147 ( 10.1071/WR9910147) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bull CM. 1995. Population ecology of the sleepy lizard, Tiliqua rugosa, at Mt Mary, South Australia. Aust. J. Ecol. 20, 393–402. ( 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1995.tb00555.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr GD, Bull CM. 2006. Exclusive core areas in overlapping ranges of the sleepy lizard, Tiliqua rugosa. Behav. Ecol. 17, 380–391. ( 10.1093/beheco/arj041) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr GD, Bull CM. 2006. Movement patterns in the monogamous sleepy lizard (Tiliqua rugosa): effects of gender, drought, time of year and time of day. J. Zool. 269, 137–147. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00091.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bull CM. 2000. Monogamy in lizards. Behav. Process. 51, 7–20. ( 10.1016/S0376-6357(00)00115-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leu ST, Kappeler PM, Bull CM. 2011. Pair-living in the absence of obligate biparental care in a lizard: trading-off sex and food? Ethology 117, 758–768. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01934.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godfrey SS, Sih A, Bull CM. 2013. The response of a sleepy lizard social network to altered ecological conditions. Anim. Behav. 86, 763–772. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.07.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubas G, Bull CM. 1992. Food addition and home range size of the lizard Tilqua rugosa. Herpetologica 48, 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerr GD, Bull CM, Burzacott D. 2003. Refuge sites used by the scincid lizard Tiliqua rugosa. Austral Ecol. 28, 152–160. ( 10.1046/j.1442-9993.2003.01268.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerr GD, Bull CM. 2006. Interactions between climate, host refuge use, and tick population dynamics. Parasitol. Res. 99, 214–222. ( 10.1007/s00436-005-0110-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bull CM, Burzacott D. 2002. Changes in climate and in the timing of pairing of the Australian lizard, Tiliqua rugosa: a 15-year study. J. Zool. 256, 383–387. ( 10.1017/S0952836902000420) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leu ST, Bashford J, Kappeler PM, Bull CM. 2010. Association networks reveal social organization in the sleepy lizard. Anim. Behav. 79, 217–225. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.11.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leu ST, Kappeler PM, Bull CM. 2011. The influence of refuge sharing on social behaviour in the lizard Tiliqua rugosa. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 837–847. ( 10.1007/s00265-010-1087-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. 2010. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 85, 935–956. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185x.2010.00141.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auburn ZM, Bull CM, Kerr GD. 2008. The visual perceptual range of a lizard, Tiliqua rugosa. J. Ethol. 27, 75–81. ( 10.1007/s10164-008-0086-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McElreath R. 2015. Statistical rethinking—a Bayesian course with R examples, 1st edn Boca Raton, FL: CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.R Core Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org.

- 49.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67, 1–48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McElreath R. 2015. Rethinking: statistical rethinking book package. R package version 1.57.

- 51.Stan Development Team. 2015. Stan modeling language user's guide and reference manual, version 2.6.1. URL http://mc-stan.org/.

- 52.Nolet BA, Mooij WM. 2002. Search paths of swans foraging on spatially autocorrelated tubers. J. Anim. Ecol. 71, 451–462. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00610.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fryxell JM, Hazell M, Börger L, Dalziel BD, Haydon DT, Morales JM, McIntosh T, Rosatte RC. 2008. Multiple movement modes by large herbivores at multiple spatiotemporal scales. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19 114–19 119. ( 10.1073/pnas.0801737105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frair JL, Merrill EH, Visscher DR, Fortin D, Beyer HL, Morales JM. 2005. Scales of movement by elk (Cervus elaphus) in response to heterogeneity in forage resources and predation risk. Landsc. Ecol. 20, 273–287. ( 10.1007/s10980-005-2075-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bull CM, Freake M. 1999. Home-range fidelity in the Australian sleepy lizard, Tiliqua rugosa. Aust. J. Zool. 47, 125–132. ( 10.1071/ZO99021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleming CH, Calabrese JM, Mueller T, Olson KA, Leimgruber P, Fagan WF. 2014. From fine-scale foraging to home ranges: a semivariance approach to identifying movement modes across spatiotemporal scales. Am. Nat. 183, E154–E167. ( 10.1086/675504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyer N, Réale D, Marmet J, Pisanu B, Chapuis J-L. 2010. Personality, space use and tick load in an introduced population of Siberian chipmunks Tamias sibiricus. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 538–547. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01659.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duckworth RA, Badyaev AV. 2007. Coupling of dispersal and aggression facilitates the rapid range expansion of a passerine bird. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15 017–15 022. ( 10.1073/pnas.0706174104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Getz WM, Fortmann-Roe S, Cross PC, Lyons AJ, Ryan SJ, Wilmers CC. 2007. LoCoH: nonparameteric kernel methods for constructing home ranges and utilization distributions. PLoS ONE 2, e207 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000207) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aplin LM, Farine DR, Morand-Ferron J, Cole EF, Cockburn A, Sheldon BC. 2013. Individual personalities predict social behaviour in wild networks of great tits (Parus major). Ecol. Lett. 16, 1365–1372. ( 10.1111/ele.12181) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edelsparre AH, Vesterberg A, Lim JH, Anwari M, Fitzpatrick MJ. 2014. Alleles underlying larval foraging behaviour influence adult dispersal in nature. Ecol. Lett. 17, 333–339. ( 10.1111/ele.12234) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korsten P, et al. 2010. Association between DRD4 gene polymorphism and personality variation in great tits: a test across four wild populations. Mol. Ecol. 19, 832–843. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data included in the paper are available through Dryad: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.h4dt0.