Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the protective effects of melatonin (MLT) on hypertension-induced renal injury and identify its mechanism of action. Twenty-four healthy male Wistar rats were divided into a sham control group (n=8), which was subjected to sham operation and received vehicle treatment (physiological saline intraperitoneally at 0.1 ml/100 g), a vehicle group (n=8), which was subjected to occlusion of the left renal artery and vehicle treatment, and the MLT group (n=8), which was subjected to occlusion of the left renal artery and treated with MLT (10 mg/kg/day). Pathological features of the renal tissues were determined using hematoxylin and eosin staining and Masson staining. Urine protein, serum creatinine (Scr), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to determine the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Furthermore, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was conducted to determine the mRNA expression of HO-1, ICAM-1, eNOS and iNOS. A marked decrease in blood pressure was noticed in the MLT group at week 4 compared with that of the vehicle group (P<0.01). Furthermore, MLT treatment attenuated the infiltration of inflammatory cells and oedema/atrophy of renal tubules. MLT attenuated hypertension-induced increases in urine protein excretion, serum creatinine and MDA as well as decreases in SOD activity in renal tissues. Furthermore, MLT attenuated hypertension-induced increases in iNOS and ICAM-1 as well as decreases in eNOS and HO-1 expression at the mRNA and protein level. In conclusion, the results of the present study indicated that MLT had protective roles in hypertension-induced renal injury. Its mechanism of action is, at least in part, associated with the inhibition of oxidative stress.

Keywords: melatonin, hypertension, oxidative stress, renal injury

Introduction

In animals with hypertension-induced renal injury, excessive accumulation of oxygen free radicals was observed together with down-regulation of antioxidase, indicating that oxidative stress has a crucial role in hypertension-induced renal injury (1). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, have been reported to be closely associated with the pathogenesis of hypertension and renal damage (2,3). The underlying mechanisms may be as follows: i) ROS affects vascular resistance via inactivating nitric oxide, resulting in arteriolar vasoconstriction and elevation of peripheral hemodynamic resistance; and ii) ROS may cause lesions in renal tissues (4).

Increasing evidence has revealed that hypertension is an independent risk factor for end-stage renal disease (5,6). However, the exact mechanism has remained to be sufficiently defined. It has been indicated that oxygen free radicals are able to trigger the elevation of blood pressure by inactivating nitric oxide, which finally raises the systemic vascular resistance (7). Reactive oxygen species also induce cellular injury and contribute to fibrosis and formation of atherogenic oxidized lipoproteins (8). Based on these facts, the present study hypothesized that the hypertension-induced renal injury is, at least in part, due to elevated generation of oxygen free radicals.

Melatonin (MLT) has been reported to ameliorate renal ischemic re-perfusion injury through its radical-scavenging activity (9,10). However, only few studies have been conducted to investigate its roles in hypertension-induced renal injury (11). The present study aimed to investigate the roles of MLT in hypertensive rats with renal damage.

Materials and methods

Animals

Healthy male Wistar rats (weighing 180–220 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Shanxi Medical University (Taiyuan, China). The rats were housed with a 12 h light/dark cycle, at 37°C, in an atmosphere containing 75% humidity. All animal were provided with ad libitum access to food and water. All the experiments were performed according to the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (NIH Publication no. 86–23, revised 1985) and the regulation of the Committee on the Use and Care of Animals of Fudan University (Shanghai, China), and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanxi Medical University (Taiyuan, China).

Preparation of hypertensive rats

The animals were subjected to occlusion of the left renal artery as previously described (12). In brief, the rats were anesthetized using 10% chloral hydrate. The renal artery of the left kidney was exposed and clipped with an artery clamp. In the sham control group, a sham procedure, which included the entire surgery expect the artery clipping, was applied.

Experimental design

Rats were divided into a sham control group (n=8), which was subjected to sham operation and received vehicle treatment (physiological saline intraperitoneally at 0.1 ml/100 g), a vehicle group (n=8), which was subjected to occlusion of the left renal artery and vehicle treatment, and the MLT group (n=8), which was subjected to occlusion of the left renal artery and injected intraperitoneally with MLT (10 mg/kg/day; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The animals were sacrificed with 10% chloral hydrate (Huayueyang Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) at week 12 after treatment.

Creatinine assay

Determination of serum creatinine was performed by Jaffe's reaction (13). In brief, aortic blood samples were obtained and centrifuged to separate the serum. Serum creatinine was determined with an automated system (Express 550 Analyzer; Ciba Corning Diagnostic Corp, East Walpole, MA, USA).

Determination of urine protein

Urine samples were collected 24 h prior to scarification of the animals with sterilized devices (Metrical GRID Trade Co., Ltd, Kunshan, China). The urine protein concentration was determined using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (product code B-0770; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) method as previously described (14).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay and superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay

MDA in the renal tissues was determined using a kit purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK; cat. no. ab118970) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The activity of SOD was determined using the SOD assay kit (cat. no. KT-034; Kamiya Biomedical Company, Seattle, WA, USA) using the V-5100H spectrophotometer (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Pathological analysis

For the pathological analysis, the renal tissues were treated using conventional procedures, including formalin fixation, dehydration and embedding. Subsequently, the sections (3 µm) were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Alfa Aesar, Shanghai, China) and Masson's trichrome (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. The pathological results were evaluated by two members of staff blinded to the study. The degree of injury was evaluated according to the damaged area of renal tubules using the following scoring system: 0, no injury; 1, injury in <10%; 2, injury in 11–25%; 3, injury in 26–45%; 4, injury in 46–75%; and 5, injury in >75% of the observed area. The evaluation was performed in 10 randomly selected fields in each slice, and was observed under a magnification of 200x.

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

In the present study, the mRNA expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) was determined using RT-PCR amplification. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent TRIzol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Shanghai, China). according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized with a random primer (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) using the SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR amplification was performed using the primers and amplification conditions listed in Table I. GAPDH was amplified under the same reaction conditions, accordingly, to serve as the internal standard. Finally, the PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels and analyzed using a Gel Documentation E-Gel® Imager system (Invitrogen Life Technologies).

Table I.

Primer sequences and amplification conditions of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Amplification conditions |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | F, CAGGTGCTATTCCCAGCCCAACA R, CATTCTGTGCAGTCCCAGTGAGGAA |

94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 61°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; 72°C for 5 min |

| eNOS | F, TTCTGGCAAGACCGATTACACGACAT R, AAAGGCGGAGAGGACTTGTCCAAA |

94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; 72°C for 5 min |

| HO-1 | F, GGGAAGGCCTGGCTTTTTT R, CACGATAGAGCTGTTTGAACTTGGT |

94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; 72°C for 5 min |

| ICAM-1 | F, GTGAGCGTCCATATTTAGGCATGG R, ACAGACACTAGAGGAGTGAGCAGG |

94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 59.6°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; 72°C for 5 min |

| GAPDH | F, AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC R, TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC |

94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 57.8°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 60 sec; 72°C for 5 min |

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis based on the Streptavidin-Biotin Complex was performed according to a previously published method (15). The primary antibodies were HO-1 (1:300; cat. no. sc-136960; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), ICAM-1 (1:150; cat. no. sc-1511; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), iNOS (1:100; cat. no. sc-650; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and eNOS (1:200; ab195944; Abcam). β-Actin (1:200; cat. no. sc-130301; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) served as the loading control. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from the Gene Tex Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test and χ2 test were performed to carry out inter-group comparisons. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

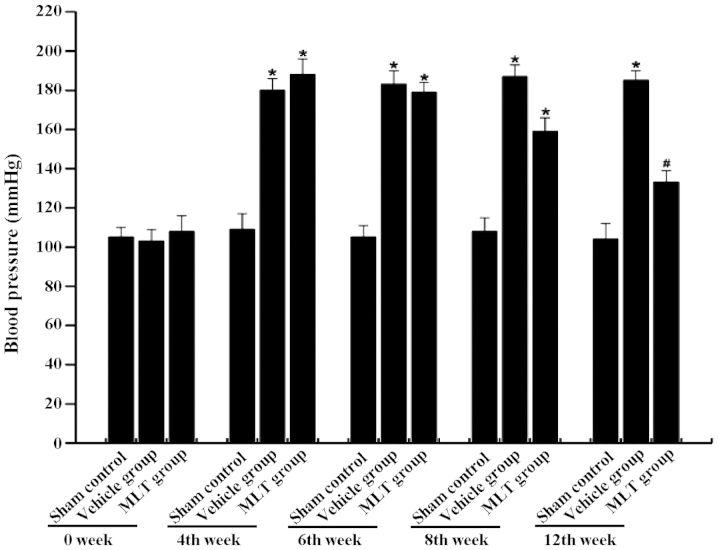

MLT attenuates hypertension-associated increases in blood pressure

The blood pressure in each group was monitored at weeks 0, 4, 6, 8 and 12 of MLT treatment. Compared with the sham control group, a significant increase in blood pressure was observed in the vehicle group at weeks 4, 6, 8 and 12 (P<0.01) (Fig. 1). In the MLT group, a significant increase in blood pressure was observed at weeks 4, 6 and 8 (P<0.05). However, MLT treatment significant attenuated the hypertension-induced increase in blood pressure at week 12 compared with that in the vehicle group (P<0.01).

Figure 1.

MLT decreases the blood pressure in rats with renal injury. Prior to sacrification of the animals, the blood pressure was monitored at weeks 0, 4, 6, 8 and 12. No statistical difference was observed in the blood pressure at the baseline levels between the different groups. The blood pressure was markedly increased in the vehicle group compared with that in the sham control. After treatment with MLT, a significant decrease in the blood pressure was observed at week 12 compared with that in the vehicle group. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.01, compared with sham control group; #P<0.01, compared with vehicle group. MLT, melatonin.

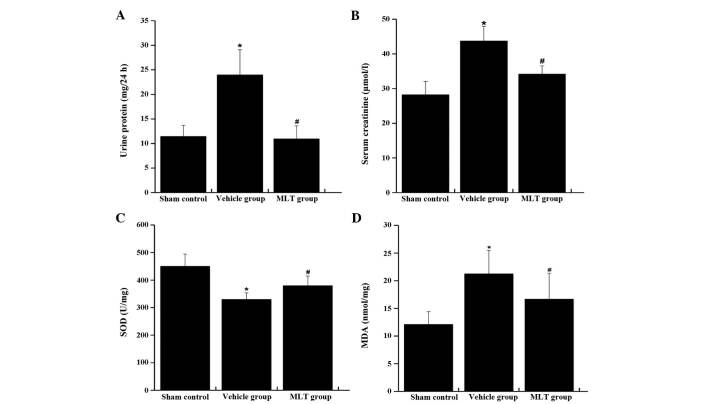

MLT attenuates hypertension-induced increases in urine protein excretion and serum creatinine

The excretion of urine protein and the concentration of serum creatinine were markedly elevated in the vehicle group compared with those in the sham control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2A and B). In the group treated with MLT, the increases in urine protein and serum creatinine were attenuated compared with those in the vehicle group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Expression of urine protein, serum creatinine, SOD and MDA at week 12 in different groups. (A) MLT was able to reduce the expression of urine protein in rats with renal injury induced by hypertension. (B) MLT modulated the expression of serum creatinine in rats with renal injury induced by hypertension. (C) MLT increased the SOD activity in rats with renal injury induced by hypertension. (D) The expression of MDA was reduced in the animals with administration of MLT. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.01, compared with sham control group; #P<0.01, compared with vehicle group. SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; MLT, melatonin.

MLT attenuates hypertension-induced decreases of SOD and increases of MDA in renal tissues

The SOD activity in renal tissues showed marked decrease in the vehicle group compared with that in the sham control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2C). In the vehicle group, the expression of MDA was markedly increased compared with that in the sham control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2D). Of note, the activity of SOD was rescued and the expression of MDA was attenuated by treatment with MLT (P<0.05).

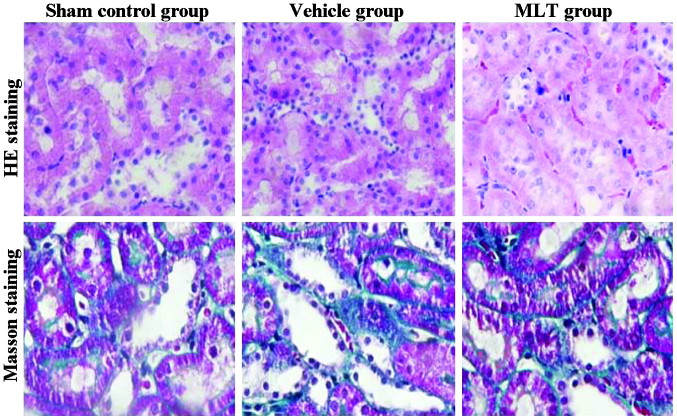

MLT reduces the infiltration of inflammatory cells and oedema/atrophy of renal tubules after hypertension-induced renal injury

H&E staining and Masson's staining was performed to determine the pathological features of the renal tissues. In the sham control group, the renal tissues were clearly presented, and the renal tubular epithelial cells were intact and aligned in order. In the vehicle group, vacuolar degeneration and granular degeneration was revealed in the renal tubular epithelial cells. Infiltration of inflammatory cells, oedema and atrophy of renal tubules were also observed. Of note, these pathological changes were attenuated in the group treated with MLT (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

HE staining and Masson staining of the renal tissues (magnification, ×200). MLT, melatonin; HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

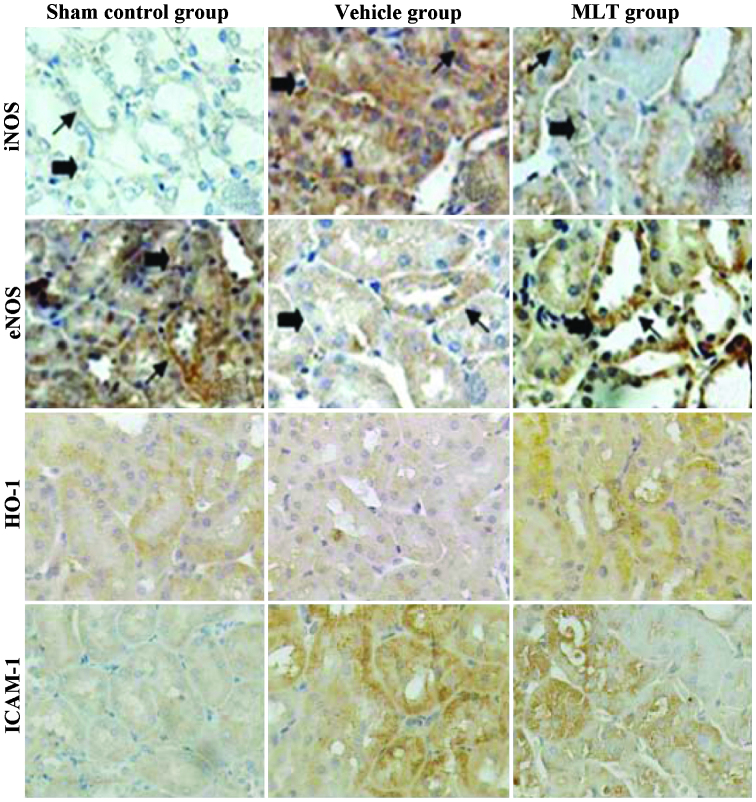

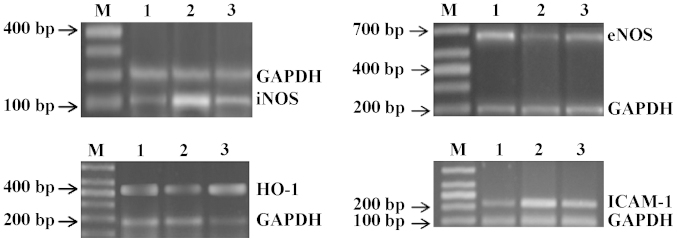

MLT modulates the expression of iNOS, eNOS, HO-1 and ICAM-1

Immunohistochemical analysis showed that iNOS, eNOS, HO-1 and ICAM-1 were mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of the renal tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 4). A minority of iNOS protein was detected in the nuclei as well. In addition, ICAM-1 was also detected in renal parenchyma. In the sham control group, the expression of ICAM-1 and iNOS was weakly positive; however, their expression was enhanced in the hypertensive rats. Compared with the vehicle group, the expression of iNOS and ICAM-1 was significantly attenuated in the MLT group. The expression of HO-1 and eNOS was significantly decreased in the vehicle group compared with that in the sham control group. However, in the rats treated with MLT, the expression of HO-1 and eNOS was significantly increased compared with that in the vehicle group. In parallel with the protein expression of iNOS, eNOS, HO-1 and ICAM-1, RT-PCR showed the same effects of hypertension and MLT treatment on the associated mRNA expression levels (Fig. 5): iNOS and ICAM-1 mRNA was elevated in the hypertensive rats compared with that in the animals of the sham control group, while these increases were attenuated by treatment with MLT. With regard to the mRNA expression of HO-1 and eNOS, a significant decrease was observed in the hypertensive rats, which was rescued by MLT treatment (P<0.01).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of iNOS, eNOS, HO-1 and ICAM-1. Magnification, ×400. Arrows indicate positive staining. MLT, melatonin; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

Figure 5.

MLT modulates the mRNA expression of iNOS, eNOS, HO-1 and ICAM-1 genes. Lanes: M, marker; 1, sham control group; 2, vehicle group; 3, MLT group. GAPDH served as the internal standard. MLT, melatonin.

Discussion

Oxidative stress has been considered to have important roles in the genesis and development of hypertension-induced renal injury (16). The present study aimed to investigate the protective effects of MLT, an effective anti-oxidant, in hypertensive rats. The results indicated that MLT attenuated in creases in blood pressure as well as renal injury in hypertensive rats.

Proteinuria has been reported to be clearly associated with an increased risk of mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (17). To date, urine protein and serum creatinine have been recognized as effective screening tools for the substantial risks associated with proteinuria (18,19). In the present study, the excretion of urine protein and serum creatinine was elevated in the vehicle group at week 12, indicating reduced renal function. Pathological analysis at week 12 indicated severe injury of the right renal tubule, which was characterized by an aberrant structure, vacuolar degeneration and granular degeneration of renal tubular epithelial cells, infiltration of inflammatory cells, as well as oedema and atrophy of the renal tubules. Of note, in the group treated with MLT, the excretion of urine protein and the concentration of serum creatinine was markedly reduced compared with that in the vehicle group. In addition, the pathological changes were attenuated, including alleviation of vacuolar degeneration, granular degeneration of renal tubular epithelial cells and oedema of renal tubules. All of these results demonstrated that MLT exerted a protective effect against renal injury in hypertensive rats.

In a previous study, abnormalities in the lipid peroxidation were observed in patients with renal disorders (20). MDA is a product of lipid peroxidation induced by oxidants and oxidative stress (21), and has been speculated to have important roles in the pathogenesis of renal diseases. In the present study, the generation of MDA in renal tissues was elevated in the vehicle group, indicating that oxidative stress generated in the kidneys also contributed to the elevation of blood pressure. However, the increases of MDA were attenuated in the group treated with MLT. SOD constitutes the first line of defence against reactive oxygen species (22). In the present study, the activity of SOD was markedly increased in the MLT group compared with that in the vehicle group. All of these results indicated that MLT reduced oxidative stress in renal tissues.

In normal renal tissues, the expression of iNOS is comparatively low; however, in renal tissues with pathologic disorders, its expression is significantly upregulated, and is considered the main source for the generation of nitric oxide, which is a major effector molecule of hypertension (23). Under normal pathological conditions, eNOS is the major source of nitric oxide; however, in renal tissues with pathological lesions, a de-coupling process of eNOS was induced, which resulted in the generation of O2− (24). Finally, massive apoptosis and necrosis were reported in renal tubular epithelial cells following hypertension (24). In the present study, the expression of iNOS was markedly upregulated in the hypertensive vehicle group, which was attenuated in the group treated with MLT. With regard to eNOS, the expression in the vehicle group was markedly downregulated, which was attenuated in the group treated with MLT. Based on these results, it was speculated that the mechanism of action of MLT may involve the elevated generation of nitric oxide in renal tubular epithelial cells through downregulating the generation of iNOS and upregulation of eNOS in renal tissues, finally resulting in a decrease in blood pressure and attenuation of renal tubular injury.

The expression of ICAM-1 reflects the infiltration of inflammatory cells (25). In the vehicle group, the expression of ICAM-1 was markedly increased, which was attenuated in the group treated with MLT. HO-1 has been reported to have protective effects in renal tissues, serving as the rate-limiting enzyme of catalyzing hemocrystallin into biliverdin and carbon monoxide (26). In the present study, the expression of HO-1 was markedly reduced in the vehicle group compared with that in the sham control. However, treatment with MLT rescued HO-1 levels following hypertension. It is therefore speculated that MLT has protective effects against renal injury through inhibiting the infiltration of inflammatory cells and enhancing the expression of HO-1.

In conclusion, MLT was able to alleviate hypertension and associated renal injury in rats. This protective effect may be associated with the reduction of oxidative stress, inhibition of infiltration of inflammatory cells and the enhancement of anti-oxidant molecules by MLT.

References

- 1.Zhou XJ, Laszik Z, Wang XQ, Silva FG, Vaziri ND. Association of renal injury with increased oxygen free radical activity and altered nitric oxide metabolism in chronic experimental hemosiderosis. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1905–1914. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swei A, Lacy FA, DeLano FA, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Oxidative stress in the Dahl hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1997;30:1628–1633. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.30.6.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah SV, Baliga R, Rajapurkar M, Fonseca VA. Oxidants in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:16–28. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uehara Y, Kawabata Y, Shirahase H, Wada K, Hashizume Y, Morishita S, Numabe A, Iwai J. Oxygen radical scavengers and renal protection by indapamide diuretic in salt-induced hypertension of Dahl strain rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22(Suppl 6):S42–S46. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199312050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson R, Morrissey E. Risk factors for end-stage renal disease among minorities. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:2415–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tozawa M, Iseki K, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Ikemiya Y, Takishita S. Blood pressure predicts risk of developing end-stage renal disease in men and women. Hypertension. 2003;41:1341–1345. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000069699.92349.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaziri ND, Liang K, Ding Y. Increased nitric oxide inactivation by reactive oxygen species in lead-induced hypertension. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1492–1498. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaziri ND, Oveisi F, Ding Y. Role of increased oxygen free radical activity in the pathogenesis of uremic hypertension. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1748–1754. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, Flores LJ, Reiter RJ. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;42:28–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sener G, Sehirli AO, Keyer-Uysal M, Arbak S, Ersoy Y, Yegen BC. The protective effect of melatonin on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat. J Pineal Res. 2002;32:120–126. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.1848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F447–F454. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00264.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiesel P, Mazzolai L, Nussberger J, Pedrazzini T. Two-kidney, one clip and one-kidney, one clip hypertension in mice. Hypertension. 1997;29:1025–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.29.4.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toora BD, Rajagopal G. Measurement of creatinine by Jaffe's reaction-determination of concentration of sodium hydroxide required for maximum color development in standard, urine and protein free filtrate of serum. Indian J Exp Biol. 2002;40:352–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lott JA, Stephan VA, Pritchard KA., Jr Evaluation of the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method for urinary protein. Clin Chem. 1983;29:1946–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chilkoti A, Tan PH, Stayton PS. Site-directed mutagenesis studies of the high-affinity streptavidin-biotin complex: Contributions of tryptophan residues 79, 108 and 120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1754–1758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Siegmund B, Lucia MS, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL. Neutrophil-independent mechanisms of caspase-1- and IL-18-mediated ischemic acute tubular necrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1083–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulks M, Stout RL, Dolan VF. Urine protein/creatinine ratio as a mortality risk predictor in non-diabetics with normal renal function. J Insur Med. 2012;43:76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Côté AM, Brown MA, Lam E, von Dadelszen P, Firoz T, Liston RM, Magee LA. Diagnostic accuracy of urinary spot protein: Creatinine ratio for proteinuria in hypertensive pregnant women: Systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336:1003–1006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39532.543947.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakoush O, Grubb A, Rippe B, Tencer J. Urine excretion of protein HC in proteinuric glomerular diseases correlates to urine IgG but not to albuminuria. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1904–1909. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ongajooth L, Ongajyooth S, Likidlilid A, Chantachum Y, Shayakul C, Nilwarangkur S. Role of lipid peroxidation, trace elements and anti-oxidant enzymes in chronic renal disease patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 1996;79:791–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negre-Salvayre A, Coatrieux C, Ingueneau C, Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alscher RG, Erturk N, Heath LS. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:1331–1341. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kröncke KD, Fehsel K, Kolb-Bachofen V. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in human diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:147–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Oliveira-Sales EB, Nishi EE, Boim MA, Dolnikoff MS, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR. Upregulation of AT1R and iNOS in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) is essential for the sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in the 2K-1C Wistar rat model. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:708–715. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang Q, Hendricks RL. Interferon gamma regulates platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 expression and neutrophil infiltration into herpes simplex virus-infected mouse corneas. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1435–1447. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motterlini R, Foresti R, Bassi R, Green CJ. Curcumin, an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, induces heme oxygenase-1 and protects endothelial cells against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00294-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]