ABSTRACT

Bis-(3′-5′) cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) controls the lifestyle transition between the sessile and motile states in many Gram-negative bacteria, including the opportunistic human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Under laboratory conditions, high concentrations of c-di-GMP decrease motility and promote biofilm formation, while low concentrations of c-di-GMP promote motility and decease biofilm formation. Here we sought to determine the contribution of c-di-GMP signaling to biofilm formation during P. aeruginosa-mediated catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI). Using a murine CAUTI model, a decrease in CFU was detected in the bladders and kidneys of mice infected with strains overexpressing the phosphodiesterases (PDEs) encoded by PA3947 and PA2133 compared to those infected with wild-type P. aeruginosa. Conversely, overexpression of the diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) encoded by PA3702 and PA1107 increased the number of bacteria in bladder and significantly increased dissemination of bacteria to the kidneys compared to wild-type infection. To determine which of the DGCs and PDEs contribute to c-di-GMP signaling during infection, a panel of PA14 in-frame deletion mutants lacking DGCs and PDEs were tested in the CAUTI model. Results from these infections revealed five mutants, three containing GGDEF domains (ΔPA14_26970, ΔPA14_72420, and ΔsiaD) and two containing dual GGDEF-EAL domains (ΔmorA and ΔPA14_07500), with decreased colonization of the bladder and dissemination to the kidneys. These results indicate that c-di-GMP signaling influences P. aeruginosa-mediated biofilms during CAUTI.

IMPORTANCE Biofilm-based infections are an important cause of nosocomial infections, since they resist the immune response and traditional antibiotic treatment. Cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a second messenger that promotes biofilm formation in many Gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Here we determined the contribution of c-di-GMP signaling to catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), an animal model of biofilm-based infection. P. aeruginosa with elevated levels of c-di-GMP during the initial infection produces an increased bacterial burden in the bladder and kidneys. Conversely, low concentrations of c-di-GMP decreased the bacterial burden in the bladder and kidneys. We screened a library of mutants with mutations in genes regulating c-di-GMP signaling and found several mutants that altered colonization of the urinary tract. This study implicates c-di-GMP signaling during CAUTI.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen that is a leading cause of nosocomial infections, including catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and surgical site infection (SSI) (1). In CAUTI, dissemination of bacteria from the catheter can lead to pyelonephritis and bacteremia. The common theme for these infections is the ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms on the surfaces of medical devices and implants (2, 3). Once formed, P. aeruginosa biofilms are more resistant to antibiotics (4–6) and phagocytic immune cells (7). Thus, the mechanism whereby P. aeruginosa forms biofilms in vivo is under investigation.

P. aeruginosa is a model organism for the study of biofilm formation under laboratory conditions (2, 3, 8, 9). Numerous studies have revealed that cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a second messenger that promotes the transition of planktonic, motile bacteria to sessile biofilms (10, 11). In P. aeruginosa, c-di-GMP regulates these processes through allosteric binding to many protein receptors to alter their function. c-di-GMP binds the FleQ transcriptional regulator (12), leading to the repression of the flagellum genes (13) and the activation of the psl and pel exopolysaccharide operons (14) as well as the surface adhesin CdrA (15). In addition to transcriptional regulation, c-di-GMP binds to PelD to activate the production of the Pel exopolysaccharide (16, 17) and to FimX to repress type IV pilus-mediated twitching motility (18, 19). Together, these c-di-GMP receptor proteins act in concert to transition planktonic bacteria to biofilms in response to elevated levels of c-di-GMP.

In the cell, c-di-GMP is generated from two GTPs by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) (20, 21) and removed through linearization by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) containing either the EAL (22, 23) or HD-GYP domain (24, 25). P. aeruginosa utilizes c-di-GMP signaling extensively and carries 40 genes that contain DGC or PDE domains. The functions of these genes in phenotypes regulated by c-di-GMP have been studied systematically using transposon insertion mutants (26), overexpression plasmids (26), and in-frame deletion mutants (27). Overexpression of a subset of DGCs elevated levels of c-di-GMP in the cell and the corresponding increase in biofilm formation, while overexpression of a subset of PDEs reduced biofilm formation (26). Transposon insertion mutants in general had more subtle defects in biofilm formation, suggesting the possibility of functional redundancy between two or more of the genes encoding DGC and PDE (26). Recently, a collection of in-frame deletion mutants was generated and characterized for c-di-GMP-regulated phenotypes (27). Multiple mutants had defects in flagellum-based and type IV pilus-based motility as well as biofilm formation (27). Together, these studies indicate that the regulation of cellular levels of c-di-GMP is complex.

In the present study, we sought to determine whether c-di-GMP signaling contributes to the colonization of the bladder and dissemination to the kidneys during CAUTI by utilizing strains overexpressing DGCs and PDEs. Strains overexpressing DGCs were able to colonize the bladder and significantly increased the dissemination to the kidneys compared to the wild type. Conversely, strains overexpressing PDE had reduced colonization of the bladder and dissemination into the kidneys. These results indicated that c-di-GMP signaling contributes to CAUTI. We utilized the in-frame deletion mutant library to determine if any of the DGCs or PDEs was the primary contributor to c-di-GMP signaling during CAUTI. A subset of these in-frame deletion mutants was selected based on changes in in vitro biofilm formation, polysaccharide production, and motility-related phenotypes and tested in the chronic CAUTI model. From these studies, 5 mutants, three containing DGC domains (ΔPA14_26970, ΔPA14_20110 [siaD], and ΔPA14_72420) and two containing dual DGC-PDE domains (ΔmorA and ΔPA14_07500), showed a 1-log reduction in colonization in the bladder. Since all five of these mutants showed defects in swimming and/or twitching motility, in-frame deletion mutants of flagellin (ΔfliC) and type IV pili (ΔpilA) were tested in the CAUTI model. We found that neither flagella nor type IV pili contribute to colonization of the bladder during CAUTI. Our results suggest that c-di-GMP signaling, through the actions of multiple DGCs, contributes to CAUTI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth.

All bacterial strains used in this study were grown in Luria broth (LB) medium at 37°C overnight. For the PA14 strains harboring pMMB plasmids for DGC and PDE overexpression, strains were grown in LB with 15 μg/ml gentamicin overnight and subcultured for 4 h with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) prior to infections. Cells were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% tryptone (PBS-T). The inoculum was serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates to determine concentration. George A. O'Toole kindly provided the collection of PA14 DGC and PDE in-frame deletion mutants. A list of strains used in this study is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PA14 | Wild type | 33 |

| PA14 pMMB PA3702 | wspR overexpression | 26 |

| PA14 pMMB PA1107 | roeA overexpression | 26 |

| PA14 pMMB PA2133 | PA2133 overexpression | 26 |

| PA14 pMMB PA3947 | rocR overexpression | 26 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_16500 (wspR) | wspR in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_50600 (roeA) | roeA in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_49890 (yfiN) | yfiN in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_26970 | PA14_26970 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_53310 | PA14_53310 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_56280 (sadC) | sadC in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_04420 | PA14_04420 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_20110 (siaD) | siaD in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_72420 | PA14_72420 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_42220 (mucR) | mucR in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_60870 (morA) | morA in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_66320 (dipA) | dipA in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_65540 (fimX) | fimX in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_53140 (rbdA) | rbdA in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_56790 (bifA) | bifA in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_21190 | PA14_21190 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_07500 | PA14_07500 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_71850 | PA14_71850 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_15810 (rocR) | rocR in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_36990 | PA14_36990 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_36260 | PA14_36260 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_59790 (pvrR) | pvrR in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_14530 | PA14_14530 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔPA14_63210 | PA14_63210 in-frame deletion | 27 |

| PA14 ΔfliC | fliC in-frame deletion | 26 |

| PA14 ΔpilA | pilA in-frame deletion | 26 |

Biofilm assays.

PA14 strains containing the pMMB plasmids were grown overnight in LB with 15 μg/ml gentamicin. Cultures were diluted 1:100 in LB with gentamicin and in the presence or absence of 1 mM IPTG. Biofilms were set up in 96-well polystyrene plates and incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 24 h. Unattached cells were washed away with water three times, and the remaining biofilms were then stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Stained cells were resuspended in 30% acetic acid, and absorbance was measured 590 nm in a spectrophotometer.

Murine CAUTI model.

The P. aeruginosa-mediated CAUTI model was as described previously (28, 29). Briefly, female CF-1 mice were anesthetized and catheterized with a 0.5-cm piece of polyethylene catheter tubing in the bladder. After emptying the contents of the bladder, 3 × 107 bacteria were inoculated into the bladder through the guide catheter. Mice infected with strains containing pMMB plasmids were given 1 mM IPTG through their drinking water to induce the tac promoter. The mice were infected for 14 days and sacrificed. The bladders and kidneys were isolated, homogenized, serially diluted, and plated on LB plates for CFU counts. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

c-di-GMP levels during initial infection affect colonization of bladder and kidneys.

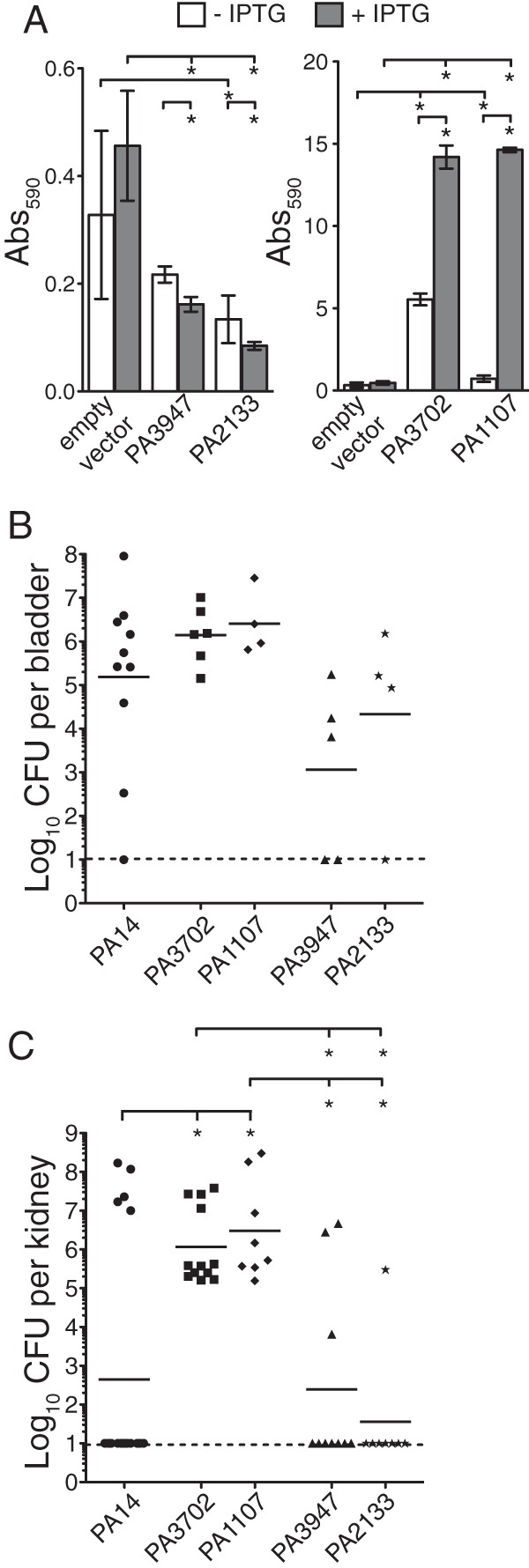

We are interested in determining whether genes participating in P. aeruginosa biofilm formation in vitro contribute to in vivo biofilm-based infection. Previous data indicated that P. aeruginosa formed biofilms during the murine model of CAUTI independently of the Pel and Psl exopolysaccharides (29). Here we tested whether the c-di-GMP signaling pathway, which also regulates P. aeruginosa biofilm formation in vitro, participates during CAUTI. To determine if either increasing or decreasing the concentration of c-di-GMP at the onset of infection would affect the colonization in the bladder or dissemination to the kidneys during CAUTI, mice were inoculated with wild-type PA14, strains that overexpressed DGCs (PA14 pMMB PA3702 and PA14 pMMB PA1107), and strains that overexpressed PDEs (PA14 pMMB PA3947 and PA14 pMMB PA2133). These overexpression strains were initially tested to confirm their in vitro biofilm phenotypes. In the absence of IPTG, DGCs PA1107 and PA3702 produced 2- and 10-fold more biofilm, respectively, than the PA14 empty-vector control. Meanwhile, PDEs PA2133 and PA3047 produced slightly less biofilm than the empty vector. These results indicate that the tac promoter of these genes allows expression in the absence of inducer. As expected, induction of DGCs PA1107 and PA3702 with IPTG resulted in an additional 18- and 2-fold increase in biofilm formation, respectively, compared to that with uninduced PA1107 and PA3702. Conversely, induction of PDEs PA2133 and PA3947 reduced biofilm formation approximately 2-fold compared to that with uninduced PA2133 and PA3947 (Fig. 1A). Compared to wild-type PA14, overexpression of DGCs PA1107 and PA3702 increased biofilm formation approximately 30-fold, while overexpression of PDEs PA2133 and PA3947 reduced biofilm formation 5- and 2-fold, respectively (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Overexpression of DGCs and PDEs during initial infection affects colonization of the bladder and kidneys. (A) In vitro biofilms for DGCs and PDEs expressed on pMMB plasmids in the presence or absence of 1 mM IPTG. (B and C) Bladders (B) and kidneys (C) from mice infected with PA14 (circles), PA14 pMMB PA3702 (squares), PA14 pMMB PA1107 (diamonds), PA14 pMMB PA3947 (triangles), or PA14 pMMB PA2133 (stars). Each symbol represents an individual organ. Bars represent geometric means. Asterisks indicate P values of ≤0.05. Dashed lines represent the limit of detection.

In CAUTI, there was a higher number of CFU detected in the bladders of mice infected with PA14 pMMB PA3702 (1.4 × 106 CFU/bladder) and PA14 pMMB PA1107 (2.6 × 106 CFU/bladder) than in mice infected with wild-type PA14. In contrast, fewer CFU were detected in the bladders of mice infected with PDE strains PA14 pMMB PA3947 (1.1 × 103 CFU/bladder) and PA14 pMMB PA2133 (2.2 × 104 CFU/bladder) than in those infected with the wild type (1.5 × 105 CFU/bladder) (Fig. 1B). In the kidneys, significantly more CFU were detected in mice infected with DGC strain PA14 pMMB PA3702 (1.2 × 106 CFU/kidney) and PA14 pMMB PA1107 (3.0 × 106 CFU/kidney) than in those infected with the wild type (4.4 × 102 CFU/kidney) (Fig. 1C). In fact, CFU were detected in all kidneys from mice infected with PA14 pMMB PA3702 and PA14 pMMB PA1107 compared to the wild type, where CFU were detected in roughly half of the kidneys (Fig. 1C). In contrast, similar numbers of CFU were detected in the kidneys of mice infected with PA14 pMMB PA3947 (2.5 × 102 CFU/kidney) and PA14 pMMB PA2133 (3.6 × 101 CFU/kidney) compared to wild-type-infected mice. These data indicate that infection with P. aeruginosa that initially elevated c-di-GMP signaling increased colonization in the bladder and dissemination and replication in the kidneys during CAUTI. In contrast, infection with P. aeruginosa that initially reduced c-di-GMP signaling decreased colonization in the bladder. Together, these results indicate that c-di-GMP signaling contributes to CAUTI.

Deletion of specific GGDEF and/or EAL domain-containing genes reduces colonization of the urinary tract during CAUTI.

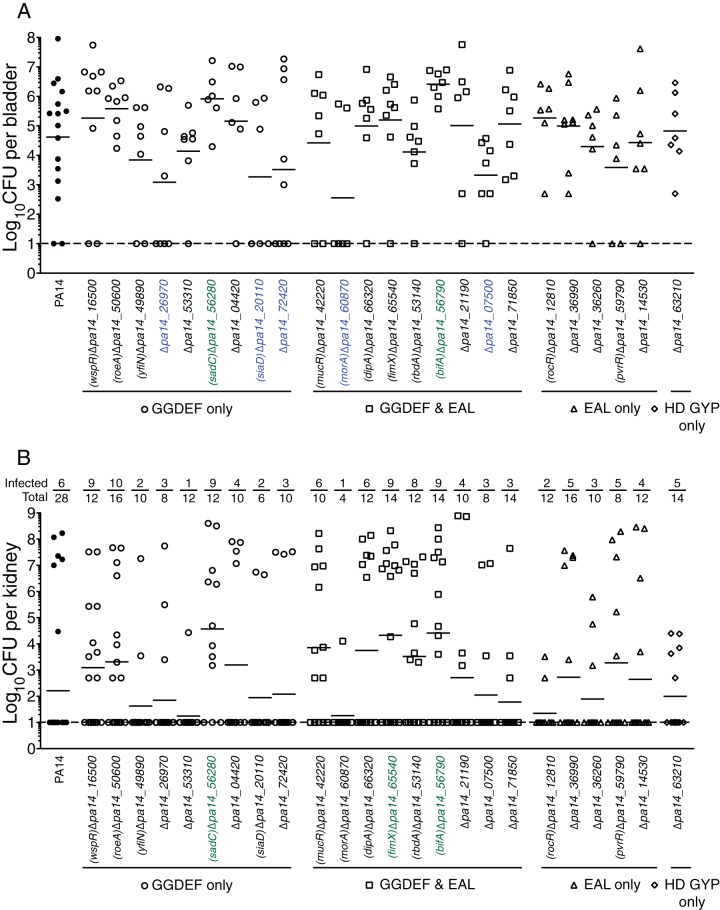

We sought to determine the physiologically relevant DGC and/or PDE that contributes to CAUTI. Based on sequence analysis of the PA14 strain, there are 40 predicted DGCs and/or PDEs (16 containing the GGDEF domain only, 16 containing GGDEF-EAL, 5 containing EAL only, and 3 containing HD-GYP only) (26). The O'Toole lab has previously generated a collection of 40 individual in-frame deletion mutants of each of these genes and tested these mutants for phenotypic changes, including increased or decreased biofilm formation, motility, and Pel polysaccharide production (27). In this study, 24 mutants (9 containing the GGDEF domain only, 9 containing GGDEF-EAL [dual domain], 5 containing EAL only, and one containing HD-GYP only) that have been previously reported to regulate phenotypic changes in vitro were tested using the CAUTI model for altered colonization of the urinary tract and dissemination. Of the mutants with mutations in genes encoding only the DGC domain, the ΔPA14_26970, ΔPA14_20110 (siaD), and ΔPA14_72420 mutants showed a reduction of greater than 1 log for the geometric mean of the number of CFU recovered from the bladder compared to the PA14 strain (Fig. 2A). Of the mutants with mutations in genes encoding both the GGDEF and EAL domains, the ΔPA14_60870 (morA) and ΔPA14_07500 mutants showed a 1-log reduction in the CFU recovered from the bladder (Fig. 2A). In addition to mutants that showed reduction in colonization of the bladder, two mutants, the ΔPA14_56280 (sadC) and ΔPA14_56790 (bifA) mutants, showed an increase in the CFU recovered from the bladder that is 1 log higher than that for the PA14 strain. The mutants with mutations in genes encoding only PDE domains (EAL or HD-GYP) all performed similarly to the wild type (Fig. 2A). In contrast to colonization, dissemination from the bladder to the kidneys and replication within the kidneys appears to occur stochastically in that most mice have either a disseminating infection with a high number of CFU in the kidneys or no infection at all. We have analyzed the data by providing the geometric mean of the CFU in all kidneys (Fig. 2, solid bars) and a ratio of the number of infected kidneys to the total number of kidneys above each data set. Several of the mutants were able to disseminate and replicate at a higher frequency than the wild type and had at least a 1-log increase in the geometric mean. Of the genes encoding DGCs, ΔPA14_56280 (sadC) mutant dissemination and replication occurred at a frequency of 75%, and the geometric mean was 3.7 × 104 CFU/kidney, while the wild type had a dissemination and replication frequency of 21% and a geometric mean of 1.6 × 102 CFU/kidney. Mutants with mutations in genes encoding GGDEF-EAL domains, ΔPA14_65540 (fimX) and ΔPA14_56790 (bifA), had at least a 1-log increase in the number of CFU detected in the kidneys, with geometric means of 2.1 × 104 CFU/kidney and 2.6 × 104 CFU/kidney, respectively. Of all the mutants tested, the ΔPA14_56280 (sadC) and ΔPA14_56790 (bifA) mutants were the only ones that were able to colonize the bladder and kidneys better than the wild type. Most of the mutants had a similar mean CFU/kidney as the wild type (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that there are specific DGCs and/or PDEs that can either increase or decrease the colonization of the bladder and dissemination to the kidneys during CAUTI.

FIG 2.

Deletion of specific DGCs and PDEs affects the colonization of the bladder and dissemination to the kidneys during CAUTI. Results for bladders (A) and kidneys (B) from mice infected with PA14 with in-frame deletions in genes containing the GGDEF domain only (circles), GGDEF and EAL (squares), EAL only (triangles), or HD GYP only (diamonds) are shown. Each symbol represents an individual organ. Bars represent geometric means. Dashed lines represent the limit of detection. Deletion mutants highlighted in green are those mutants with at least 1-log increase in CFU detected in either the bladder or the kidneys compared to that for wild-type PA14. Deletion mutants highlighted in blue are those mutants with at least a 1-log decrease in CFU detected in the bladder compared to that for wild-type PA14.

Requirement of flagella and type IV pili in CAUTI.

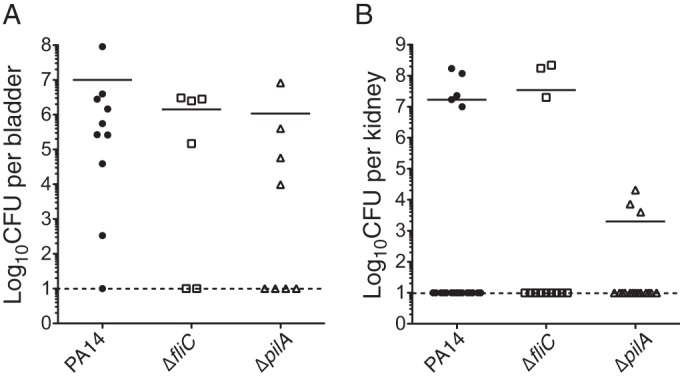

Since our results suggest that a subset of DGC and/or PDE genes contributes to CAUTI, we tested whether known c-di-GMP-regulated processes contribute to CAUTI. Previously, the Pel and Psl exopolysaccharides, which mediate biofilm formation in vitro, were shown to be dispensable during CAUTI. We asked whether flagella and type IV pili that contribute to acute infections also participate during CAUTI. Mutants with in-frame deletion mutations of the major flagellin (ΔfliC) and major pilus (ΔpilA) were tested in the murine model of CAUTI. The ΔfliC and ΔpilA mutants colonized the bladder with means of 1.4 × 106 CFU and 1.1 × 106 CFU, respectively (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that flagella and type IV pili are not the primary determinant for P. aeruginosa to colonize the bladder. The ΔfliC (3 out of 16 kidneys) and ΔpilA (3 out of 16 kidneys) mutants were able to disseminate into the kidney at a frequency similar to that for PA14 (5 out of 20 kidneys). However, the geometric mean CFU of the ΔpilA mutant in the kidneys was reduced to 2.0 × 103 CFU (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that flagella are dispensable for colonization and dissemination, while type IV pili are dispensable for colonization in the bladder but contribute to dissemination.

FIG 3.

Type IV pili contribute to dissemination to the kidneys. Results for bladders (A) and kidneys (B) from mice infected with wild-type PA14, PA14 ΔfliC, or PA14 ΔpilA are shown. Each symbol represents an individual organ. Bars represent geometric means. Dashed lines represent the limit of detection.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that induction of DGCs immediately prior to infection enhances colonization in the bladder, indicating that c-di-GMP contributes to biofilm formation during CAUTI. In contrast, induction of PDEs immediately prior to infection reduces colonization of the bladder. Since bacteria not attached to the catheter are likely rapidly removed by urination, these results also support the idea that the c-di-GMP signaling pathway positively regulates biofilm formation during CAUTI. Similar observations have been made in other chronic infection models for P. aeruginosa involving implant of foreign devices. One murine model is based on the insertion of silicone catheters into the peritoneal cavity (30). The contribution of c-di-GMP signaling was tested by utilizing a strain of P. aeruginosa harboring an inducible PDE, YhjH, from E. coli (31). Twenty-four hours postimplantation, the expression of YhjH was induced by injection of arabinose into the peritoneal cavity. Strains with YhjH had more bacteria disseminate into the peritoneal cavity and the spleen than those with the vector control, indicating that the reduction in c-di-GMP levels in the bacteria correlated with detachment of P. aeruginosa from the preformed biofilm (31). In a separate study, a ΔyfiR mutant, which has constitutively activated YfiN DGC activity, was subjected to a subcutaneous catheter model of chronic infection (32). Despite having a reduced growth rate associated with elevated levels of c-di-GMP, the ΔyfiR mutant was able to persist within the catheters. Taken together, the previous studies and our current studies suggest that alteration of the c-di-GMP signaling pathway can shift the outcome of the infection. Increasing the c-di-GMP concentration enhances the association with the foreign body, while decreasing the c-di-GMP concentration increases the dispersion of P. aeruginosa.

To determine the DGC and PDE that are relevant for CAUTI, we tested 24 in-frame deletion mutants from the 40 total in the PA14 in-frame deletion mutant library of DGCs and PDEs. These strains were selected based on their in vitro c-di-GMP-related phenotypes, including biofilm formation, Pel polysaccharide production, and motility (27). Of the mutants tested, we found that mutants with mutations in GGDEF-containing genes (ΔPA14_02110 [siaD], ΔPA14_26970, and PA14_72420) and dual GGDEF-EAL-containing genes (ΔPA14_07500 and ΔPA14_60870 [morA]) showed a reduction in colonization in the bladder. These mutants have previously been characterized extensively for biofilm formation, Congo red binding, swimming motility, swarming motility, and twitching motility (27). Analysis of these mutants for Congo red binding indicates that the ΔPA14_07500 and ΔPA14_60870 (morA) mutants failed to produce the Pel polysaccharide, whereas the Δpa14_02110 (siaD) and Δpa14_26970 mutants increased production of Pel. Analysis of these mutants for flagellum-mediated swimming and swarming motility revealed that all five of the mutants were defective in swimming and swarming motility. Analysis of these mutants for twitching motility indicated that the ΔPA14_02110 (siaD), ΔPA14_26970 and PA14_72420 mutants had a reduced twitch zone, whereas the ΔPA14_07500 and ΔPA14_60870 (morA) mutants had wild-type twitching motility. Comparison of the in vivo CAUTI results with the in vitro assays indicate that a common defect is in swimming motility. However, this is likely not the case, for two reasons. First, the ΔPA14_14530, ΔPA14_21190 and ΔPA14_66320 (dipA) mutants, with similar swimming and swarming defects (27), were able to colonize during CAUTI similarly to the wild type. Second, the ΔfliC strain was able to cause CAUTI similarly to PA14. Since mutations in the exopolysaccharides (29), flagella, and type IV pili are not required for P. aeruginosa to cause CAUTI, the c-di-GMP-regulated process that contributes to CAUTI is likely through an unknown mechanism that is likely specific to the urinary tract. Furthermore, the moderate reduction in bacterial burden for any of the single mutants with mutations in genes encoding DGC and PDE suggests that there is functional redundancy of DGCs in the urinary tract. Future testing of combinatorial mutants that show moderate defects may resolve this apparent redundancy. Furthermore, there are an additional 16 DGC and/or PDE mutants out of the 40 total mutants that were not tested in this study and were previously shown not to have in vitro phenotypes that differed from those of the wild type. These mutants should be tested in future studies to determine their involvement in CAUTI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank George A. O'Toole for generously providing the P. aeruginosa PA14 library of in-frame DGC and PDE deletion mutants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert DM, Pollock DA, Fridkin SK. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 29:996–1011. doi: 10.1086/591861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsek MR, Singh PK. 2003. Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:677–701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickel JC, Ruseska I, Wright JB, Costerton JW. 1985. Tobramycin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells growing as a biofilm on urinary catheter material. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 27:619–624. doi: 10.1128/AAC.27.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colvin KM, Gordon VD, Murakami K, Borlee BR, Wozniak DJ, Wong GC, Parsek MR. 2011. The pel polysaccharide can serve a structural and protective role in the biofilm matrix of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 7:e1001264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng BS, Zhang W, Harrison JJ, Quach TP, Song JL, Penterman J, Singh PK, Chopp DL, Packman AI, Parsek MR. 2013. The extracellular matrix protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by limiting the penetration of tobramycin. Environ Microbiol 15:2865–2878. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jesaitis AJ, Franklin MJ, Berglund D, Sasaki M, Lord CI, Bleazard JB, Duffy JE, Beyenal H, Lewandowski Z. 2003. Compromised host defense on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: characterization of neutrophil and biofilm interactions. J Immunol 171:4329–4339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryder C, Byrd M, Wozniak DJ. 2007. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr Opin Microbiol 10:644–648. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsek MR, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2008. Pattern formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hengge R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickman JW, Harwood CS. 2008. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol 69:376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baraquet C, Harwood CS. 2013. Cyclic diguanosine monophosphate represses bacterial flagella synthesis by interacting with the Walker A motif of the enhancer-binding protein FleQ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:18478–18483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318972110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baraquet C, Murakami K, Parsek MR, Harwood CS. 2012. The FleQ protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa functions as both a repressor and an activator to control gene expression from the pel operon promoter in response to c-di-GMP. Nucleic Acids Res 40:7207–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borlee BR, Goldman AD, Murakami K, Samudrala R, Wozniak DJ, Parsek MR. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol 75:827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee VT, Matewish JM, Kessler JL, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Lory S. 2007. A cyclic-di-GMP receptor required for bacterial exopolysaccharide production. Mol Microbiol 65:1474–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitney JC, Colvin KM, Marmont LS, Robinson H, Parsek MR, Howell PL. 2012. Structure of the cytoplasmic region of PelD, a degenerate diguanylate cyclase receptor that regulates exopolysaccharide production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 287:23582–23593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazmierczak BI, Lebron MB, Murray TS. 2006. Analysis of FimX, a phosphodiesterase that governs twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 60:1026–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarro MV, De N, Bae N, Wang Q, Sondermann H. 2009. Structural analysis of the GGDEF-EAL domain-containing c-di-GMP receptor FimX. Structure 17:1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Ohana P, Mayer R, Braun S, de Vroom GE, van der Marel A, van Boom JH, Benziman M. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan C, Paul R, Samoray D, Amiot NC, Giese B, Jenal U, Schirmer T. 2004. Structural basis of activity and allosteric control of diguanylate cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:17084–17089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tal R, Wong HC, Calhoon R, Gelfand D, Fear AL, Volman G, Mayer R, Ross P, Amikam D, Weinhouse H, Cohen A, Sapir S, Ohana P, Benziman M. 1998. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. J Bacteriol 180:4416–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barends TR, Hartmann E, Griese JJ, Beitlich T, Kirienko NV, Ryjenkov DA, Reinstein J, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Schlichting I. 2009. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial light-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Nature 459:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature07966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Crossman LC, Spiro S, He YW, Zhang LH, Heeb S, Camara M, Williams P, Dow JM. 2006. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:6712–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Bellini D, Caly DL, McCarthy Y, Bumann M, An SQ, Dow JM, Ryan RP, Walsh MA. 2014. Crystal structure of an HD-GYP domain cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase reveals an enzyme with a novel trinuclear catalytic iron centre. Mol Microbiol 91:26–38. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulasakara H, Lee V, Brencic A, Liberati N, Urbach J, Miyata S, Lee DG, Neely AN, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Ausubel FM, Lory S. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2839–2844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha DG, Richman ME, O'Toole GA. 2014. Deletion mutant library for investigation of functional outputs of cyclic diguanylate metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3384–3393. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00299-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurosaka Y, Ishida Y, Yamamura E, Takase H, Otani T, Kumon H. 2001. A non-surgical rat model of foreign body-associated urinary tract infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Immunol 45:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole SJ, Records AR, Orr MW, Linden SB, Lee VT. 2014. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by exopolysaccharide-independent biofilms. Infect Immun 82:2048–2058. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01652-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen LD, Moser C, Jensen PO, Rasmussen TB, Christophersen L, Kjelleberg S, Kumar N, Hoiby N, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T. 2007. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing on biofilm persistence in an in vivo intraperitoneal foreign-body infection model. Microbiology 153:2312–2320. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen LD, van Gennip M, Rybtke MT, Wu H, Chiang WC, Alhede M, Hoiby N, Nielsen TE, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2013. Clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa foreign-body biofilm infections through reduction of the cyclic Di-GMP level in the bacteria. Infect Immun 81:2705–2713. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00332-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malone JG, Jaeger T, Manfredi P, Dotsch A, Blanka A, Bos R, Cornelis GR, Haussler S, Jenal U. 2012. The YfiBNR signal transduction mechanism reveals novel targets for the evolution of persistent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis airways. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]