Abstract

Brain function emerges from hierarchical neuronal structure that spans orders of magnitude in length scale, from the nanometre-scale organization of synaptic proteins to the macroscopic wiring of neuronal circuits. Because the synaptic electrochemical signal transmission that drives brain function ultimately relies on the organization of neuronal circuits, understanding brain function requires an understanding of the principles that determine hierarchical neuronal structure in living or intact organisms. Recent advances in fluorescence imaging now enable quantitative characterization of neuronal structure across length scales, ranging from single-molecule localization using super-resolution imaging to whole-brain imaging using light-sheet microscopy on cleared samples. These tools, together with correlative electron microscopy and magnetic resonance imaging at the nanoscopic and macroscopic scales, respectively, now facilitate our ability to probe brain structure across its full range of length scales with cellular and molecular specificity. As these imaging datasets become increasingly accessible to researchers, novel statistical and computational frameworks will play an increasing role in efforts to relate hierarchical brain structure to its function. In this perspective, we discuss several prominent experimental advances that are ushering in a new era of quantitative fluorescence-based imaging in neuroscience along with novel computational and statistical strategies that are helping to distil our understanding of complex brain structure.

Keywords: brain structure, fluorescence imaging, multiscale analysis and modelling

1. Introduction

Understanding the closely inter-related structure and function of the human brain presents one of the greatest scientific challenges of this century. Since the seminal discoveries of basic aspects of neuronal morphology and connectivity by Ramon y Cajal over 100 years ago [1,2], our understanding of brain function has remained limited by our inability to efficiently measure brain structure at multiple length scales that range from single synapses to the whole intact organ itself. However, recent advances in fluorescence imaging such as multiplexed super-resolution imaging [3–5] and rapid whole-brain imaging in model organisms using light-sheet microscopy [6] are, together with a rapidly emerging set of genetic engineering tools, increasing our ability to characterize brain structure in a holistic, multiscale manner. As these multi-resolution datasets emerge, new data analysis strategies should, in our view, ideally aim to offer integrative model-based descriptions that facilitate functional interpretation of these datasets across multiple imaging modalities and length scales.

Electron microscopy (EM) is the gold standard for resolving brain structure in utmost detail at the nanometre scale, offering the highest spatial resolution and great promise to generate complete neuronal wiring diagrams, or ‘connectomes’, of the brain. Such efforts are, however, intrinsically limited to fixed, non-living samples and generally lack the ability to resolve specific molecular identities in a multiplexed manner. Moreover, the generation and interpretation of EM datasets present major challenges that typically limit application of this ultra-high-resolution structural procedure to small sample sizes and only a handful of laboratories. In contrast, fluorescence imaging or light microscopy (LM) is a widely accessible tool that now enables the structural characterization of synaptic molecules up to entire mouse brains in a multiplexed manner using sample clearing techniques [7,8]. While a major strength of fluorescence imaging is its applicability to live organisms, we limit our review here to fixed samples with the aim of quantitatively characterizing hierarchical brain structure across length scales.

Because of the very large size of the datasets produced by both EM and LM imaging modalities, computational tools play an instrumental role in analysing, annotating, organizing and interpreting these datasets. Multiscale approaches such as correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) that integrate EM and LM datasets [9–11] are of utmost interest to benefit from these datasets in a complementary manner. This is particularly the case as we attempt to understand not only the connectomic wiring of the brain, but also the synaptic composition of intact brain samples with highly heterogeneous and variable distributions of molecules that ultimately govern synaptic transmission. As novel labelling and imaging techniques rapidly emerge to produce very large datasets consisting of terabytes of LM and EM data, new statistical frameworks and computational tools to characterize the multiscale nature of brain structure are expected to play a leading role in unifying these datasets to extract structural principles. While formal models of multiscale brain structure are currently lacking, we believe that the formulation of model-driven structural analysis techniques is of utmost importance in order to interpret these emerging hierarchical datasets with a view towards their unification and ultimately functional interpretation. These efforts may one day inform in vivo functional studies including electrophysiology [12,13] and whole animal behaviour [14,15], which are not treated in this perspective.

Here, we highlight recent fluorescence labelling, imaging and analysis approaches that inform our understanding of molecular and cellular organization at these diverse length scales. We posit that increasing our quantitative knowledge of hierarchical brain structure will aid in phenotypic characterization and will likely generate new avenues for understanding a range of human diseases related to molecularly and genetically identifiable targets. Because of inherent limitations of fluorescence imaging, including major challenges that are associated with the high-throughput measurement of molecular numbers and localizations, the quantification of neuronal wiring and connectivity, and whole-brain imaging of living organisms, we additionally discuss how serial EM and whole-brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used in conjunction with LM to effectively bridge scales (figure 1). For each approach, we discuss quantitative analysis and modelling strategies that are beginning to enable the integration of neuroanatomy at multiple scales. Finally, we review several examples of neuronal spheroids and cerebral organoids that are offering new opportunities to understand how genetic variation leads to human disease in patient-specific models of brain structure and function.

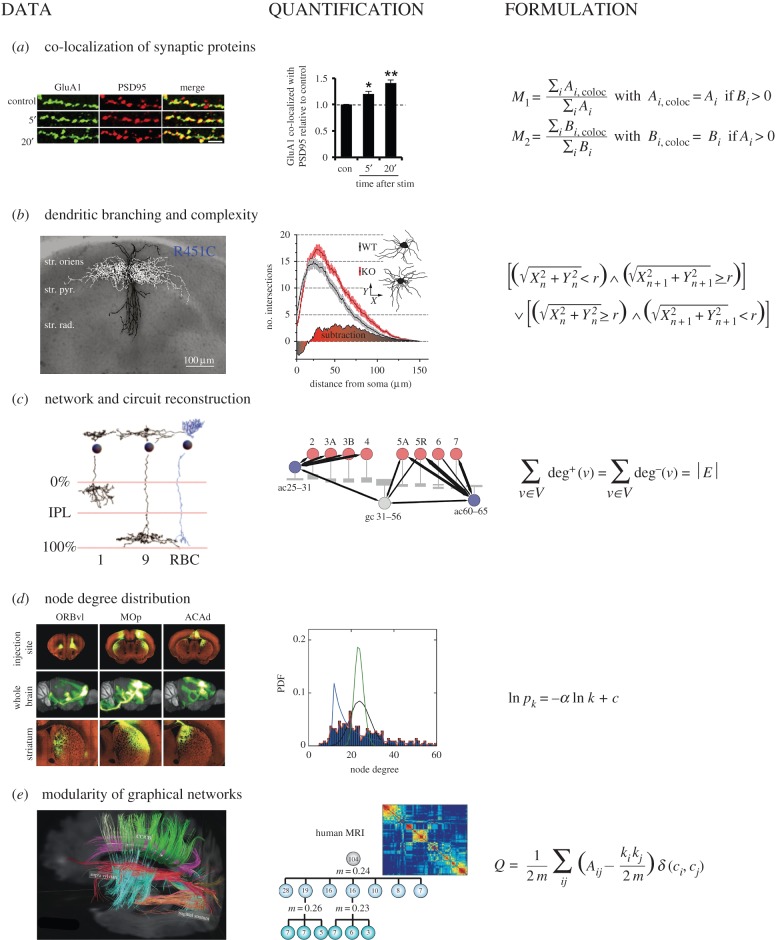

Figure 1.

Multiscale modelling of brain imaging data. (a) Co-localization of GluA1 and PSD95 in dissociated rat hippocampal neurons (left), Manders' co-localization of GluA1 and PSD95 during elevated glycine exposure relative to control conditions (centre) [16] and equations for Manders' coefficents (right). (b) Morphological changes induced by the neuroligin-3 mutation R451C in mice (left) [17], dendritic size and complexity as analysed with the Sholl method in mouse SHANK3 knockout tissue (centre) [18] and Sholl equations (right). (c) EM data (left) and circuit reconstruction (centre) in the inner plexiform layer of the mouse retina [19]. The relationship between node degree and the number of edges in a complete directed graph (right). (d) Inter-regional connectivity data (left) is used to create a node degree distribution (centre) from tracer injections at hundreds of unique sites [20]. Node degree distributions that match a power law distribution are indicative of a scale-free network structure (right). (e) Modularity and hierarchy of network maps as assessed by structural MRI data [21]. (Online version in colour.)

2. Super-resolution imaging enables multiplexed synaptic protein localization and counting

The link between mutations of synaptic scaffolding and adhesion molecules such as Shank3, neuroligin and neurexin with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia is well documented and includes associations through rare mutations, de novo copy number variations and chromosomal abnormalities [22–24]. The clinical significance of these genetic aberrations underscores the need to improve our understanding of the relation between genetic variation and synaptic molecular composition. For example, it is plausible that neuronal dysfunction stems from disruptions to pre- and post-synaptic cell adhesion complexes that stabilize synapses during development and are essential to normal synaptic transmission [25]. Understanding how such genetic variation impacts synaptic molecular organization and signal transmission is therefore of central importance in resolving brain structure. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging offers the ability to probe synaptic structure by imaging individual intact synapses with typically 20 nm spatial resolution, in principle across numerous molecular targets in a multiplexed manner [26,27].

Among several distinct super-resolution imaging approaches, localization microscopy enables the highest imaging resolution (approx. 20 nm that is well below the approx. 200 to 500 nm size of an individual synapse) by localizing single fluorophores sequentially. The single-molecule nature of localization microscopy further enables the conversion of observed units of fluorescence into quantitative counts of specific molecules using calibration standards, thereby enabling quantitative in situ proteomics within synapses. For example, recent efforts have used the localization microscopy techniques photoactivated localized microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) to measure the ultrastructure of excitatory and inhibitory synapses [3,4,26,28–30]. Specht et al. [4] used a mouse strain expressing photoconvertible constructs of the inhibitory synaptic scaffolding protein gephyrin together with a photoswitchable dye-labelled antibody to reveal sub-synaptic co-localization of gephyrin molecules with glycine receptors within individual synapses of cultured spinal cord neurons. This result is further supported by the 1 : 1 stoichiometric ratio of gephyrin to receptor-binding sites measured using a photobleaching-based single-molecule counting approach [4]. Similarly, PALM was used to show that PSD95 forms nanodomains within the post-synaptic density that concentrates AMPA receptors but not NMDA receptors [30]. The recent advent of three-dimensional super-resolution microscopy further enables mapping out the complete three-dimensional organization of synaptic proteins in single synapses. Relative spatial distributions of 10 different synaptic proteins has been determined by performing three-colour three-dimensional STORM using sequential imaging of distinct synaptic proteins using a common molecular reference [3].

While localization microscopy provides high spatial resolution, its low temporal resolution typically limits its application to fixed samples. In contrast, coordinate-targeted super-resolution methods such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy and reversible saturable optical fluorescence transitions (RESOLFT) have helped to capture the fast dynamics of neuronal structure [5,31–33]. Coordinate-targeted super-resolution microscopy relies on minimizing the illumination volume by selectively ‘turning off’ the fluorescence of a subset of molecules so that the positions of molecules can be determined more accurately. However, high laser power that is required for depleting fluorescence in STED can pose significant phototoxicity to neurons. RESOLFT minimizes the illumination volume by employing reversibly switchable fluorescent proteins whose dark state can be induced with lower laser power, improving spatial resolution by more than threefold in comparison with conventional confocal microscopy. RESOLFT has been applied to study the morphological dynamics of dendritic spines in living hippocampal brain slices [5]. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging using selective plane illumination microscopy (SPIM) allows for fast imaging of thick samples with reduced phototoxicity by using a sheet of light to selectively illuminate a thin section of the sample, providing new avenues for performing live-cell in situ super-resolution imaging [34]. The variation in sub-synaptic structures and compositions revealed by super-resolution imaging will provide new data for further characterization of synapse sub-types in addition to excitatory and inhibitory synaptic classes, which will offer crucial structural components to drive modelling of neuronal circuit function. A major future challenge is the application of whole-brain super-resolution imaging to intact samples, given limitations in light penetration. Combining synaptic protein localization with neuronal tracers that enable resolution of intact connectomic structure is a second major need that is discussed later in this perspective.

3. Electron microscopy remains the gold standard for connectomics

Despite recent advances in super-resolution imaging, to date, serial tissue sectioning and ultrastructural characterization with EM provide the most definitive datasets for full neuronal circuit reconstruction. The use of electron beams as illumination sources allows for high-resolution tracing of neuronal processes with unambiguous identification of synaptic connections. Efforts to make large-scale EM maps of mammalian brain tissue have been undertaken [19,35,36], although these approaches typically do not resolve constituent proteins within cells. Thus, characterization of synapse types with pure EM approaches is challenging because this requires the identification of a number of distinct synaptic targets [37]. Recently, different types of CLEM have been developed to combine the strengths of LM and EM, namely specificity and resolution. Embedding and fixation protocols that retain fluorescent protein function have been used for CLEM imaging of genetically labelled samples [38–40]. Oxygen-radical-generating fluorescent proteins have also been used to enhance EM contrast by locally catalysing formation of polymers that are resolvable by EM [41]. Shu et al. [42] have examined the localization of synaptic cell adhesion molecules SynCAM1 and -2 using both EM and fluorescence microscopy by tagging the target proteins with a fluorescent protein that is engineered to generate singlet oxygen with high yield upon illumination.

In contrast, other correlative methods attempt to combine EM and immunofluorescence, in which imaging is performed separately on the same or adjacent tissues samples. A major challenge of performing EM and immunofluorescence on the same sample arises from their typically mutually exclusive sample preparation procedures—fixation and embedding that is required for EM may disrupt immunoreactivity of the sample. Recent advances have improved tissue preparation procedures to preserve both the immunoreactivity and ultrastructure of thin tissue segments for pairing ultrastructure measurements with the labelling of multiple protein targets [9,43,44]. For example, improved freeze-substitution embedding methods can circumvent the use of osmium tetroxide, a common EM post-fixation step, to improve the preservation of protein epitopes in tissue during antibody labelling. The osmium-tetroxide-free embedding approach has been combined with array tomography (AT) [10,45], a multiplexed immunofluorescence microscopy technique that sequentially stains and strips the same ultrathin tissue sections with different antibodies, enabling high-resolution volumetric imaging of synaptic structures and molecular composition at the same time (figure 2) [11]. New image analysis strategies for EM are also required to improve reconstruction of long-range neuronal circuits. While new brain-wide reduced-osmium staining enables the long-range tracing of thin neurite features, including spine necks and small-calibre axons, EM tracing still requires highly involved human-assisted reconstruction [46].

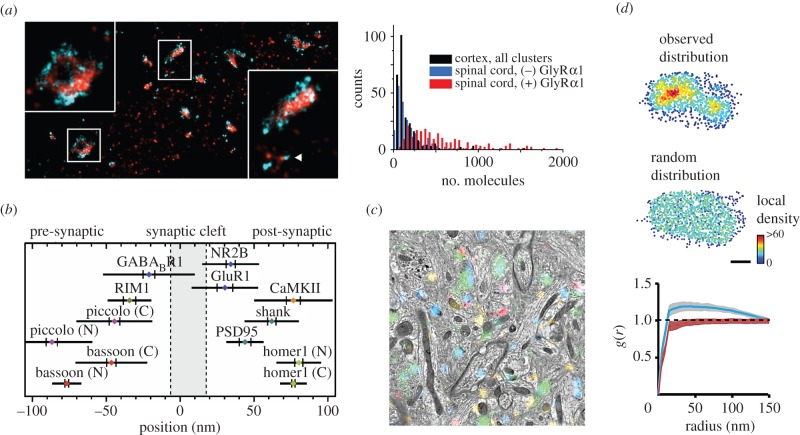

Figure 2.

Super-resolution imaging of neuronal structure. (a) (Left) PALM/STORM of mEos2-gephyrin (red) and Alexa 647-labelled endogenous GlyRa1 (cyan) in fixed spinal cord neurons shows the correspondence between the GlyR and gephyrin distributions at inhibitory synapses. Also note the co-localization (within less than 50 nm) of GlyRs and gephyrin nanoclusters (arrowhead). Scale: box width of 1.25 μm. (Right) Quantification of the number of mRFP-gephyrin molecules in cortex (black) and in spinal cord inhibitory synapses that are negative (blue) or positive (red) for endogenous GlyRa1. (b) A composite plot of the axial positions of synaptic proteins imaged using three-colour STORM. For each protein, the coloured dot specifies the mean axial position, the two vertical lines represent the associated SEM and the half-length of the horizontal bar denotes the s.d., derived from multiple synapses. (c) Molecular multiplexing with correlative EM with AT. A SEM field is shown in greyscale, with immunofluorescence for VGluT1 (light blue), glutamine synthetase (orange), synapsin-1 (green) and PSD-95 (red). (d) (Top) Single-molecule localization of PSD-95-Eos2. Individual molecules were colour coded according to their local density. (Middle) Homogeneous distribution generated by randomly sampling equal numbers of localizations is observed. Scale bar, 100 nm. (Bottom) Mean pair-correlation function of the PSD in the measured particle locations (blue) and for the simulated locations (red). Shaded areas represent 99% CIs calculated from the randomized ensembles, showing significant departures from homogeneity. (Online version in colour.)

4. Multiplexed imaging to resolve distinct cellular and molecular sub-types in intact cells and tissues

In addition to increased resolution of synaptic structures, labelling strategies that enable quantification of local protein expression levels and co-localizations provide new data that are likely to prove central to informing functional models based on underlying brain structure that account for both cellular and synaptic identities. While most current imaging modalities are limited to three or four fluorescent channels due to spectral overlap of conventional fluorophores, new multiplexing strategies are leading to compelling advances in our ability to image numerous proteins and cell types simultaneously within the same intact tissue. One such example is the use of diffusible fluorescent probes for localization microscopy, termed points accumulation in nanoscale topography (PAINT), a concept originally introduced by Sharanov and Hochstrasser in 2006 [47]. PAINT employs transiently binding fluorescent probes that interact specifically with molecular targets in order to generate transient target blinking while allowing for probe exchange using wash-out or probe dilution in physiological buffer. Transient binding kinetics enables sequential imaging of arbitrary numbers of molecular targets using a single dye type and laser source, allowing for implementation of this technique on standard fluorescence microscopes. These multiplexed imaging procedures may in principle remove the limit on the number of molecular as well as cellular sub-types that can be resolved within an intact tissue.

A number of variants of PAINT have been developed since the seminal work of Sharanov and Hochstrasser. Universal PAINT (uPAINT) is one alternative super-resolution technique that employs binding and bleaching of high-affinity antibodies to achieve single-molecule imaging and has been used to map out the dynamics and organization of AMPA receptors on the post-synaptic membrane [26]. Other variants of PAINT have employed transiently binding nucleic acid probes that can be exchanged after imaging to enable multiplexed super-resolution microscopy [48], breaking the limit of four targets that can be imaged using conventional fluorescence microscopy due to spectral overlap. Ten-target imaging of DNA nanostructures and four-target cellular imaging were demonstrated using diffusible DNA-based probes and a commercial microscope [27]. However, labelling density is a potential issue for application of DNA-PAINT to highly multiplexed imaging of targets with high density due to the need to use bulky antibodies to label targets in the current implementation. As an alternative, one recent study used protein-fragment-based probes instead of DNA-conjugated antibodies to perform PAINT [49], reporting multiplexed super-resolution imaging of the cytoskeleton and focal adhesion proteins with a considerably higher labelling density, which can similarly be envisioned to be important for imaging the crowded post-synaptic density. However, application of this technique to neurons will require the identification of appropriate protein-binding probes.

Integrating multiplexed in situ measurement of protein localization together with multiplexed measurement of messenger RNAs offers the potential to produce rich phenotypic readouts for characterizing intact brain structure molecularly including both protein and transcript localizations and expression levels [50]. Extending multiplexed imaging to live-cell samples to characterize transcript and protein transport crucial to synapse formation and maturation offers an important yet unmet challenge. Application of model-based fluorescence correlation spectroscopy may offer the ability to quantitatively count protein and transcript copy numbers in situ from fluctuation analysis of transiently binding probes [51,52], and model-based protein and RNA trajectory analysis in live cells would offer insight into local mechanisms of their regulation [53,54]. Combining synaptic protein localization studies together with in situ characterization of amyloid aggregation dynamics is also of interest [52,55]. Resolving RNA and protein localizations is particularly important for complex neuronal structures in which dendritic and axonal processes may span hundreds to thousands of cell bodies away from the soma. Here, local rates of translation and RNA/protein modifications are determined by local signalling mechanisms rather than necessarily the transcriptional state of the cell [53,56,57]. In situ characterization of cell and synapse sub-types should again prove highly useful to informing structure-based models of neuronal circuit function.

5. Quantifying molecular co-localization

Multiplexed super-resolution and conventional widefield imaging generates spatially heterogeneous datasets that report on the levels and localizations of individual proteins and RNAs distributed throughout brain tissues. These datasets offer brain region and cell-type specificity that cannot easily be achieved using bulk biochemical protein–protein association assays such as co-immunoprecipitation, or exogenous association assays such as yeast two-hybrid. Identifying the degree of co-localization of synaptic proteins in a spatially resolved manner that is specific to synapses, cells and brain regions will offer important data to inform the type and function of neuronal synapses and circuits. For example, Dani et al. [3] illustrated super-resolution strategies for calculating co-localization of numerous synaptic proteins axially along pre- and post-synaptic densities, with relevance to understanding neuronal structure that emerges at larger length scales from axonal pathfinding [58].

Early efforts in quantifying protein co-localization relied on global image analysis and intensity-based metrics, such as Pearson correlation, to detect whether two or more proteins occupy a fixed volume. An important alternative approach was introduced by Manders and colleagues in 1996, who formulated co-localization coefficients to quantify the intersection of fluorescence signals from two imaging channels of interest. Given two channels of an image that represent the fluorescence signals from proteins labelled A and B, respectively, the Manders' overlap coefficients quantify the relative intensity of each channel at their intersection [59],

|

where Ai,coloc is the pixel intensity from channel A if the value for that pixel in channel B is positive. Similarly, Bi,coloc is the pixel intensity of channel B if the value for that pixel in channel A is positive. The coefficients M1 and M2 range between 0 and 1 and are proportional to the fluorescence signal in channels A and B, respectively, but are restricted only to regions of co-localization. One recent example makes use of the Manders' overlap coefficients by quantifying the extent to which AMPAR subunits GLUA1 and GLUA2 localize to post-synaptic densities as marked by PSD95 [16]. The authors measured co-localization after glycine stimulation to detect the presence of GLUA2 subunits that render synaptic ion channels impermeable to calcium. By comparing co-localization results to those in cells that did not receive elevated glycine stimulation, the study illustrates how Manders' coefficients can easily be normalized to control conditions (figure 1a).

Manders' coefficients and other global image metrics have been improved by new techniques that place better objective bounds on intensity relatedness and statistically evaluate the presence of co-localization events [60,61]. Object-based measures of co-localization and nonlinear correlation metrics such as mutual information that have found widespread application in other fields may also prove valuable for extracting more subtle spatial relationships that are not captured by the linear Pearson and Manders' metrics. For example, Lagache et al. [62] found that object-based Ripley's K-function for co-localization showed improved robustness to noise relative to Manders' and Pearson metrics when tested on dual-channel synthetic images with Gaussian noise. As new experimental techniques enable the recording of numerous molecularly specific channels, the adoption of multiple comparison procedures will be critical to examining many pairwise relationships in these multiplexed co-localization studies. The impact of these datasets would be further enhanced if interpreted alongside measurements of the type and strength of neurotransmission at individual synapses.

6. Quantifying dendritic morphology and branching

Independent from molecular-level characterization of synapses, information on cellular geometry and location in cortical layering provides crucial information on neuron type and functional properties. Fluorescently labelled anterograde and retrograde tracers have historically played a central role in labelling neuronal branching morphology in mammalian systems. One example of a recent advance is the conjugation of bright and photostable fluorescent dyes to the conventional cholera toxin subunit B tracer, which has commonly been used in bright-field microscopy to mark multiple long-range neuroanatomical connections that may span up to centimetres, with high fidelity and contrast [63]. The fluorescent equivalent of this traditional tracer now enables multiplexed imaging of neuronal morphology and integration with alternative fluorescent labels for correlative structural studies with pre- and post-synaptic markers. Similarly, transgenic labelling strategies carry the advantage of marking adjacent neurons with distinct spectral identities (figure 3a) [64]. This ‘Brainbow’ approach has recently been modified to increase colour variety and photostability of probes, as well as used adapted mouse lines where the generation of double transgenics are not required [66].

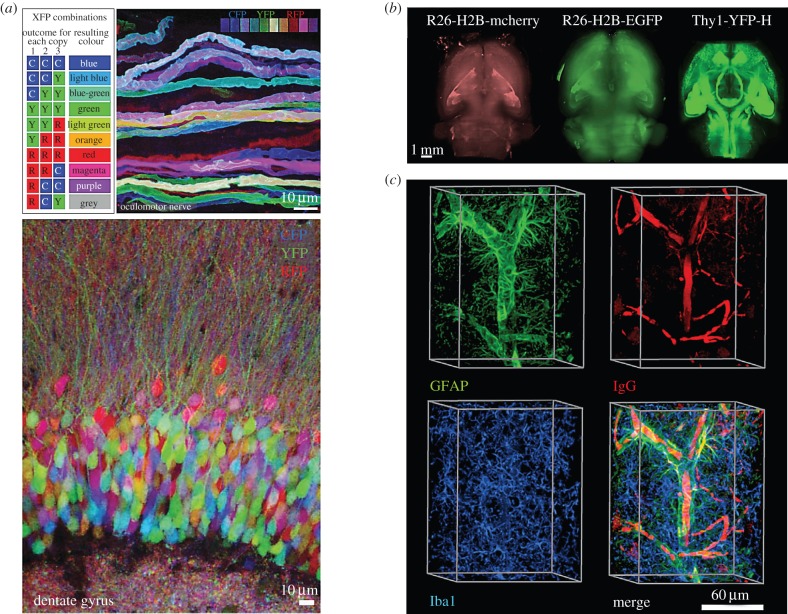

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional intact imaging of brains and organoids. (a) The Brainbow construct results in combinatorial and unique XFP expressions; oculomotor axons of Thy1-Brainbow-1.0 line H and dentate gyrus of Thy1-Brainbow-1.0 line L [64]. (b) Three-dimensional reconstructed images of mouse brains expressing various fluorescent proteins were acquired with light-sheet microscopy. Ventral-to-dorsal images of three different transgenic mouse strains [65]. (c) Pre-frontal cortex of PACT-cleared adult mouse brain sections stained with antibodies against GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein), murine immunoglobulin G (IgG) and ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) [7]. (Online version in colour.)

Once cells are fluorescently labelled and imaged, challenges remain in the quantitative analysis and model-based interpretation of the long-range shape and structure of neurons. Sholl analysis has widely been used as a method for quantifying dendritic size and complexity in studies of neuronal morphology [67], and while not directly model-based, it can in principle be used to drive network-based functional models. In this approach, concentric circles are drawn outward radially at fixed intervals from the soma. Intersection events are defined as the points where a dendrite crosses over the reference circle at a specific distance r from the soma such that the following condition is satisfied [68],

|

where Xn and Yn are the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinates of a neuritic segment and Xn+1 and Yn+1 are the coordinates of a daughter segment. The principle behind the Sholl equation is that neuritic branching events can be tallied in the concentric circles extending from the soma. In recent work with knockout mice, Sholl profiles of dendritic branching and complexity have been used to measure the morphological impact of synaptic cell adhesion proteins (figure 1b) [18].

Recently, exciting efforts have extended morphological analysis to three dimensions and allowed for disease modelling in mammalian tissue. For example, one recent study used juxtasomal biocytin injection and dimensionality reduction to describe the trans-columnar neuronal morphology in the somatosensory cortex (vS1) of rats [69]. After neuronal skeleton reconstruction, principal component analysis was performed to identify clusters of morphological patterns and assign cell types. Importantly, the authors were able to analyse the distribution of bouton density along different axonal projections for each cell type. This analysis offers new insight into how distinct cell types, characterized by overall morphology, impact columnar versus horizontal connections in the vS1. Using a similar approach, Oberlaender et al. [70] reconstructed the three-dimensional circuit of excitatory neurons in a single cortical column of the rat vibrissal cortex. Topological properties of the neurons including the distribution of somata, dendrites and thalamocortical synapses were correlated with electrophysiological recordings. These results provided an improved map of the vibrissal cortex, as well as a new understanding of how spontaneous and evoked neural spike recordings relate to cell morphology. Future progress in this area may continue to relate features of cellular shape and position to functional recordings of neuronal activity in model organisms. A major challenge for multiscale and multi-modal imaging is to integrate synaptic molecular composition with dendritic branching to relate their structure to neuronal function. The design of new labelling strategies that are amenable to high-throughput manipulations, such as enhanced adeno-associated viral vectors, will also enhance efforts to describe long-range neuronal paths that complement descriptions from MRI diffusion data.

7. Model-based whole-brain circuit reconstruction

Neuronal circuit reconstruction begins with the identification of synapses or inter-neuronal contacts and follows the trace of individual neurites back to their soma. Recent serial block-face EM studies, for example, track the frequency of synaptic and incidental cell–cell overlaps [19,35]. Binning cell inter-connections according to surface areas helps to identify sites of contact that are most likely to be involved in synaptic transmission. This node-path detection of brain structure is ideally suited to graph-based modelling that attempts to distil governing structural principles from complex networks. Graph-theoretic approaches can be used to quantify differences in neuroanatomical connectivity patterns, as well as attempt to infer their functional consequences. For example, in 2014, Oh et al. [20] at the Allen Brain Institute released data for a whole-brain connectivity matrix based on stereotaxic injection and neuronal labelling of hundreds of mouse brain regions (figure 1d). In this and related studies, summary network measures have been used to analyse long-range regional connectivity data, as well as guide the generation of new connectomic datasets.

Standard results from graph theory illustrate how structural networks can be evaluated by counting the total number of connections observed in a given system. For example, in the directed graph G = (V,E), where V and E are the set of all nodes (or vertices) and edges, respectively, the degree sum shows the relatedness between the number of incoming connections deg+(v) and outgoing connections deg−(v) at a given node. Across a complete graph, the sum of incoming node degrees should equal the sum of outgoing node degrees and match the total number of edges [72],

where deg+(v) represents the incoming connections at a specific node, deg−(v) represents outgoing connections and |E| is the total number of edges in the network system. Importantly, this and related network formulations may not be valid in cases where the complete map of the network system is not available. The violation of such a common graphical principle in the context of missing data points to the need for researchers to evaluate the assumptions and limitations of working with subsampled data from small segments of brain tissue or subsampled regional connectivity data.

Node degree distributions play an important role in describing the topological properties of a network, which can give rise to differential ability to effectively communicate long-range electrochemical signals in neuronal networks. The node degree of large, randomly generated networks, for example, follows a Poisson distribution [72], and can serve as a control profile with which to compare empirical neuronal data, as random graphs do not confer any regional specialization. Recent EM and neuronal tracer data have provided node degree distributions and offered insight into the complex network properties of neuronal tissue. In the case of the Allen Brain Map, an inter-region connectivity matrix was generated based on long-range tracts observed with high-throughput serial two-photon tomography [20]. The node degree distribution in this graph-based representation showed asymmetry and skewness towards high-degree nodes. Node degree data from the inter-region graph were modelled with a power law distribution where the probability pk of any given node having degree k is modeled with two parameters, α and c (figure 1d). This degree distribution is characteristic of a scale-free networks which are known for their fault-tolerant behaviour [72]. Such scale-free networks are grown by the addition of new nodes that connect preferentially to existing nodes that already have high degree [73]. Data from inter-regional tracer studies create down-sampled representations of brain connectivity and graphical models using such data typically rely on assumptions such as regional homogeneity (injections to a sub-area of a region is representative of its larger neighbourhood) and projection additivity (projection densities are created through linear sums of source regions) [20]. Improvements in the volume and accuracy of neuronal reconstruction data from EM may offer complete degree distributions within fixed brain regions. Similarly, advances in LM imaging that allow for the reliable detection of synaptic contact points would prove invaluable to constructing formalized models of cell-based connectivity.

8. Quantifying modularity of neuronal wiring diagrams

In addition to node degree distributions in neuronal connectomic data, other graph-based metrics offer insight into structural and functional properties of neuronal networks. Seminal studies have identified features of hierarchical and small-world architecture through the laminar patterns of connections between brain regions in macaque [74] and cat [75]. More recently, researchers have described structural hierarchy at multiple scales and in multiple model systems by quantifying the density of links within and between neuronal sub-structures. For example, Bassett et al. [21] applied Louvain community detection to the wiring diagrams of Caenorhabditis elegans as well as human structural and diffusion MRI data (figure 1e). The authors used modularity, a measure of to what extent like is connected to like, to describe the organizational hierarchy of multiple model organisms. From this analysis, they observed multiple examples of densely inter-connected modules with sparse intra-module connectivity. Similarly, Teller et al. [76] assessed calcium signalling dynamics between neurons that are organized into compact clusters in cell culture, finding significant modularity that represents a preference in the connectivity of neurons to those that are most similar in signalling activity.

In highly modular systems, the density of links inside sub-communities is much higher than the links between communities. Given a series of neuronal communities (or node types) labelled for each vertex c1, c2, …, cm, the total number of edges that runs between nodes of the same type can be summed as follows [72]:

|

where Aij is a symmetric and binarized connectivity matrix containing the value 1 for entries where nodes i and j are connected and 0 otherwise. The Kronecker delta δ(ci,cj) is a piecewise function and is set to 1 whenever two nodes belong to the same node type. The factor of 1/2 accounts for the fact that every connection is counted twice in the binarized connectivity matrix Aij. To compare the sum of within-community connections observed in real tissues, it is helpful to subtract off the number of such connections that would occur by chance. In a network with m total edges, each node i in the system can be labelled as having degree ki. Because the total number of edge ends is 2m, the probability that node j will connect to any other node randomly drawn from the graph is kj/2m. The expected number of connections between nodes i and j in a random graph is then kikj/2m. Subtracting this random connection component from the sum of within-community connections allows us to define the modularity quantity [72],

|

Modularity is an important aspect of hierarchical network structure and has been used to evaluate the cost-efficiency of mapping complex neuronal systems that are densely packed into physical space [21].

By quantitatively measuring community structure through modularity, researchers can evaluate the extent to which processing networks are supported by sparsely inter-connected modules that are each composed of highly intra-connected neurons. Such high-level network views of neuronal systems are likely to become increasingly powerful as graphical models are built on more accurate and comprehensive EM wiring diagrams and inter-region tracer data. At present, graph-theoretic approaches can serve as a quantitative analysis framework on which functional models are based and can be applied at multiple scales to convey important structural insight even when based on down-sampled connectivity data. As discussed earlier, researchers applying network models to EM, fluorescence imaging and MRI have illustrated such an approach. In the future, such frameworks will likely be amenable to direct integration and across-scale comparisons of fluorescence and diffusion-based MRI studies [77,78].

9. Neuronal spheroids and organoids as models for human disease

Given challenges in obtaining human brain tissues for phenotypic profiling and structural characterization, assaying brain structure and function in patient-derived model tissues and organs may play a central role in relating genetic variation present in neurodevelopmental and degenerative diseases with human neuronal disorders. Human-derived somatic cells are now routinely induced into pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that are subsequently differentiated into neuronal aggregates known as spheroids, which serve as tissue models. Such models are known to take on physiological features not present in two-dimensional cell cultures. For example, a recent study established a three-dimensional neuronal sprouting assay for peripheral nerve regeneration and showed that neurite length is notably higher in spheroids as compared with two-dimensional co-cultures [79]. This and related observations support the notion that three-dimensional cellular organization accounts for physiological interactions that are absent in two-dimensional counterparts. A similar example is the human-based tissue modelling of the congenital condition microcephaly. Lancaster et al. [80] highlight premature neural differentiation in microcephaly-affected patient-derived tissues, which results in a reduced expansion of radial glial cells, implying a markedly smaller size (figure 4a–c).

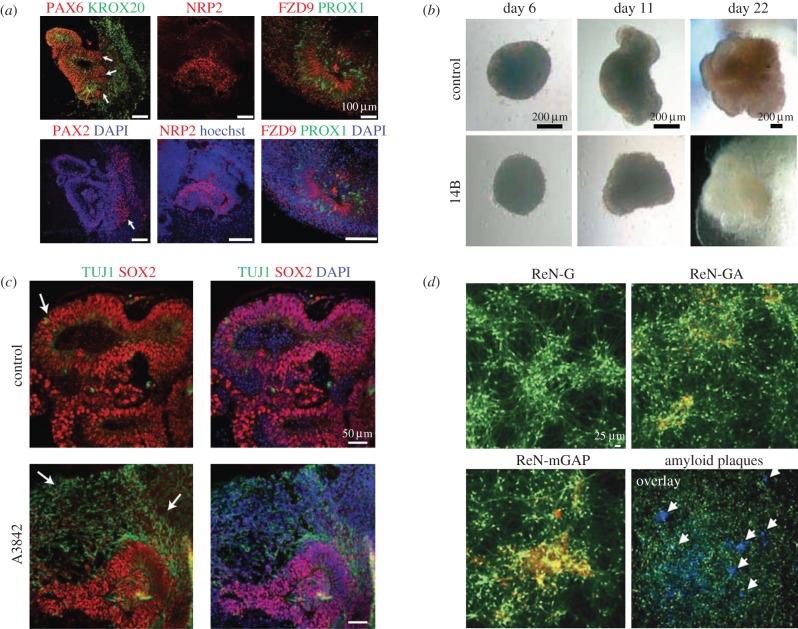

Figure 4.

Tissue and disease modelling with cerebral organoids. (a) Brain region identity is captured using human cerebral organoids; fluorescence imaging for PAX6 (forebrain marker), KROX20 (hindbrain marker) and PAX2 (hindbrain marker); hippocampal markers NRP2, FZD9, PROX1 [80]. (b) Control-derived spheroids form thick fluid-filled cortical tissues. Microcephaly patient-derived tissues (line 14B) display neuroepithelium and outgrowth of neuronal morphology as compared to control [80]. (c) Modelling of microcephaly through cerebral organoids; day 22 staining indicates higher number of neurons (TUJ1, arrows) in patient-derived tissue [80]. (d) Comparison between six-week differentiated control (ReN-G) and familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD) ReN cells (ReN-GA, ReN-mGAP). Detection of amyloid plaques in ReN-mGAP cells with Amylo-Glo (green—GFP, red—3D6 anti-amyloid-β, blue—Amylo-Glo, arrows—Amylo-Glo-positive aggregates) [81]. (Online version in colour.)

The accumulation of amyloid-β, which has been related to tauopathy in Alzheimer's patients, has also been modelled in three-dimensional culture, enabling the investigation of pathogenic mechanisms (figure 4d) [81]. With improved measures of cell fate, spheroids can be used in existing high-throughput screening and imaging modalities and high content analysis pipelines. This rise has been accompanied by complementary progress in sample preparation methods. As the study of such systems with intact and whole-brain imaging techniques becomes more broadly accessible, an important limitation of spheroids is their highly scattering nature due to their large size and lipid composition, which renders conventional LM applied to native samples ineffective.

To overcome this obstacle and fully realize the utility of structural and molecular characterization of these three-dimensional samples, effective clearing techniques are proving indispensible to improve optical transparency and permeability to labelling reagents such as antibodies and nanobodies [82,83]. Optical clearing extracts lipid structures from deep within the tissue to eliminate scattering, rendering it impossible to study cellular ultrastruture using EM or lipophilic dyes (figure 3b). While a wide variety of clearing protocols have been developed, the underlying objective of attaining optically clear specimens remains similar [7]. One approach, three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs (3DISCO), is a fast procedure based on sequential incubation with organic solvents that offers the capability to image neuronal connections in several millimetres of depth with high resolution [8]. Passive clarity technique (PACT) is an alternative approach for three-dimensional imaging that is slower than 3DISCO but uses a solvent that is compatible with commercial light-sheet instruments and offers improved diffusion of antibodies and small molecules, thereby enabling sub-cellular level molecular interrogation of the entire cleared tissue (figure 3c) [7]. Light-sheet microscopy is highly relevant as an imaging modality to combine with clearing approaches due to its deep tissue penetration, multi-view imaging and reconstruction [84], and fast acquisition rate compared with scanning confocal or two-photon microscopy. Light-sheet imaging additionally reduces phototoxicity dramatically in living specimens due to selective illumination in comparison with widefield or confocal imaging. The technique has been used to image optically cleared whole mouse brains in which EGFP was used to target hippocampal pyramidal neurons [85]. A similar study used tissue clearing and SPIM to create three-dimensional models of dendritic spines and trees in the CA1 neurons in mouse hippocampi [86]. Work by Niedworok et al. [6] employed two-colour light-sheet microscopy to identify connectivity maps in neural circuits marked using virus-mediated trans-synaptic tracing. Combining multiplexed imaging of synaptic composition and structure with light-sheet microscopy, clearing and modelling of human disease using iPSCs offers important potential for understanding the impact of genetic variation on brain structure and function, as well as identifying therapeutic targets [87]. The use of physical expansion of brain tissues to simultaneously increase optical resolution and clear tissue samples also offers great promise for in situ characterization and hierarchical neuronal structure [88]. Bridging multiscale imaging of cerebral organoid structure with quantitative characterization that drives hierarchical functional modelling is in our view an important long-term aim of multiscale modelling research into the genetic basis of human brain function and disease.

10. Outlook and future challenges

In neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD, and psychiatric diseases including schizophrenia and depression, polygenic variation contributes to disease burden and can impact high-level brain function including memory and cognition. As genetic studies of human patient populations increasingly reveal genetic variants involving synaptic proteins, the need to relate synaptic protein levels and localizations to circuit function and organization becomes increasingly pressing. Characterization of neuronal structure in a hierarchical manner is now enabled by recent advances in multi-resolution imaging and structural analysis highlighted in this perspective. Important future potential lies ahead in leveraging the convergence of imaging, labelling, sequencing and genetic engineering technologies to better understand the mechanistic basis for currently untreatable and debilitating diseases of the brain. For LM, major aims include increased capacity for multiplexed imaging and localization using advanced molecular probes, as well as developing new strategies to employ LM and EM on the same sample. Computational tools that improve our ability to localize and count synaptic molecules and labelling strategies that allow for resolution of dendritic morphology in the same sample may offer new insight into integrated network-based models of brain structure that leverage powerful graph-theoretic approaches. Model ‘organoid’ systems that enable the ability to model human disease and characterize neuronal structure, identity and function in situ offer an important new opportunity to potentially diagnose, prognose and also treat major classes of neuronal disease. Because highly heterogeneous neuronal structures, from hundreds of individual molecules expressed within single synapses to complete neuronal circuit architectures, are at the root of all brain function, multiscale EM and LM imaging, analysis and structure-based modelling of brain and organoid function is certain to play a leading role in this area.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Simon Gordonov for useful discussions.

Authors' contributions

L.H. and M.B. conceived the article. L.H., S.G, K.M. and M.B. wrote the article.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH U01-MH106011-02) to M.B. and the National Science Foundation (NSF PHY 1305537) to M.B.

References

- 1.Cajal SR. 1894. The Croonian lecture: la fine structure des centres nerveux. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 55, 444–468. ( 10.1098/rspl.1894.0063) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cajal SR. 1906. In Nobel Lectures, physiology or medicine 1901–1921.

- 3.Dani A, Huang B, Bergan J, Dulac C, Zhuang X. 2010. Superresolution imaging of chemical synapses in the brain. Neuron 68, 843–856. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Specht CG, Izeddin I, Rodriguez PC, El Beheiry M, Rostaing P, Darzacq X, Dahan M, Triller A. 2013. Quantitative nanoscopy of inhibitory synapses: counting gephyrin molecules and receptor binding sites. Neuron 79, 308–321. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Testa I, Urban NT, Jakobs S, Eggeling C, Willig KI, Hell SW. 2012. Nanoscopy of living brain slices with low light levels. Neuron 75, 992–1000. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niedworok CJ, Schwarz I, Ledderose J, Giese G, Conzelmann KK, Schwarz MK. 2012. Charting monosynaptic connectivity maps by two-color light-sheet fluorescence microscopy. Cell Rep. 2, 1375–1386. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang B, Treweek JB, Kulkarni RP, Deverman BE, Chen CK, Lubeck E, Shah S, Cai L, Gradinaru V. 2014. Single-cell phenotyping within transparent intact tissue through whole-body clearing. Cell 158, 945–958. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erturk A, Becker K, Jahrling N, Mauch CP, Hojer CD, Egen JG, Hellal F, Bradke F, Sheng M, Dodt HU. 2012. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1983–1995. ( 10.1038/nprot.2012.119) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Rijnsoever C, Oorschot V, Klumperman J. 2008. Correlative light-electron microscopy (CLEM) combining live-cell imaging and immunolabeling of ultrathin cryosections. Nat. Methods 5, 973–980. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1263) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micheva KD, Smith SJ. 2007. Array tomography: a new tool for imaging the molecular architecture and ultrastructure of neural circuits. Neuron 55, 25–36. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collman F, Buchanan J, Phend KD, Micheva KD, Weinberg RJ, Smith SJ. 2015. Mapping synapses by conjugate light-electron array tomography. J. Neurosci. 35, 5792–5807. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4274-14.2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood C, Williams C, Waldron GJ. 2004. Patch clamping by numbers. Drug Discov. Today 9, 434–441. ( 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03064-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise K, Anderson D, Hetke J, Kipke D, Najafi K. 2004. Wireless implantable microsystems: high-density electronic interfaces to the nervous system. Proc. IEEE 92, 76–97. ( 10.1109/JPROC.2003.820544) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. 2010. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1161–1169. ( 10.1038/nn.2647) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelucci F, Brene S, Mathe AA. 2005. BDNF in schizophrenia, depression and corresponding animal models. Mol. Psychiatry 10, 345–352. ( 10.1038/sj.mp.4001637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaafari N, Henley JM, Hanley JG. 2012. PICK1 mediates transient synaptic expression of GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors during glycine-induced AMPA receptor trafficking. J. Neurosci. 32, 11 618–11 630. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5068-11.2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foldy C, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. 2013. Autism-associated neuroligin-3 mutations commonly disrupt tonic endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron 78, 498–509. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peca J, Feliciano C, Ting JT, Wang W, Wells MF, Venkatraman TN, Lascola CD, Fu Z, Feng G. 2011. Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature 472, 437–442. ( 10.1038/nature09965) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmstaedter M, Briggman KL, Turaga SC, Jain V, Seung HS, Denk W. 2013. Connectomic reconstruction of the inner plexiform layer in the mouse retina. Nature 500, 168–174. ( 10.1038/nature12346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh SW, et al. 2014. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature 508, 207–214. ( 10.1038/nature13186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassett DS, Greenfield DL, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR, Moore SW, Bullmore ET. 2010. Efficient physical embedding of topologically complex information processing networks in brains and computer circuits. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000748 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000748) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betancur C, Sakurai T, Buxbaum JD. 2009. The emerging role of synaptic cell-adhesion pathways in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Neurosci. 32, 402–412. ( 10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudhof TC. 2008. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature 455, 903–911. ( 10.1038/nature07456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauthier J, et al. 2010. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7863–7868. ( 10.1073/pnas.0906232107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAllister AK. 2007. Dynamic aspects of CNS synapse formation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 425–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giannone G, et al. 2010. Dynamic superresolution imaging of endogenous proteins on living cells at ultra-high density. Biophys. J. 99, 1303–1310. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jungmann R, Avendano MS, Woehrstein JB, Dai M, Shih WM, Yin P. 2014. Multiplexed 3D cellular super-resolution imaging with DNA-PAINT and Exchange-PAINT. Nat. Methods 11, 313–318. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2835) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frost NA, Shroff H, Kong H, Betzig E, Blanpied TA. 2010. Single-molecule discrimination of discrete perisynaptic and distributed sites of actin filament assembly within dendritic spines. Neuron 67, 86–99. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoze N, Nair D, Hosy E, Sieben C, Manley S, Herrmann A, Sibarita J-B, Choquet D, Holcman D. 2012. Heterogeneity of AMPA receptor trafficking and molecular interactions revealed by superresolution analysis of live cell imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17 052–17 057. ( 10.2307/41763484) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacGillavry HD, Song Y, Raghavachari S, Blanpied TA. 2013. Nanoscale scaffolding domains within the postsynaptic density concentrate synaptic AMPA receptors. Neuron 78, 615–622. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berning S, Willig KI, Steffens H, Dibaj P, Hell SW. 2012. Nanoscopy in a living mouse brain. Science 335, 551 ( 10.1126/science.1215369) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urban NT, Willig KI, Hell SW, Nägerl UV. 2011. STED nanoscopy of actin dynamics in synapses deep inside living brain slices. Biophys. J. 101, 1277–1284. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testa I, D'Este E, Urban NT, Balzarotti F, Hell SW. 2015. Dual channel RESOLFT nanoscopy by using fluorescent state kinetics. Nano Lett. 15, 103–106. ( 10.1021/nl503058k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella Zanacchi F, Lavagnino Z, Perrone Donnorso M, Del Bue A, Furia L, Faretta M, Diaspro A. 2011. Live-cell 3D super-resolution imaging in thick biological samples. Nat. Methods 8, 1047–1049. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1744) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasthuri N, et al. 2015. Saturated reconstruction of a volume of neocortex. Cell 162, 648–661. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayworth KJ, Xu CS, Lu Z, Knott GW, Fetter RD, Tapia JC, Lichtman JW, Hess HF. 2015. Ultrastructurally smooth thick partitioning and volume stitching for large-scale connectomics. Nat. Methods 12, 319–322. ( 10.1038/nmeth.3292) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maglione M, Sigrist SJ. 2013. Seeing the forest tree by tree: super-resolution light microscopy meets the neurosciences. Nat. Neurosci 16, 790–797. ( 10.1038/nn.3403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kukulski W, Schorb M, Welsch S, Picco A, Kaksonen M, Briggs JAG. 2011. Correlated fluorescence and 3D electron microscopy with high sensitivity and spatial precision. J. Cell Biol. 192, 111–119. ( 10.1083/jcb.201009037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe S, Punge A, Hollopeter G, Willig KI, Hobson RJ, Davis MW, Hell SW, Jorgensen EM. 2011. Protein localization in electron micrographs using fluorescence nanoscopy. Nat. Methods 8, 80–84. ( 10.1038/nmeth.1537) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell K, Mitchell S, Paultre D, Posch M, Oparka K. 2013. Correlative imaging of fluorescent proteins in resin-embedded plant material. Plant Physiol. 161, 1595–1603. ( 10.1104/pp.112.212365) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grabenbauer M, Geerts WJ, Fernadez-Rodriguez J, Hoenger A, Koster AJ, Nilsson T. 2005. Correlative microscopy and electron tomography of GFP through photooxidation. Nat. Methods 2, 857–862. ( 10.1038/nmeth806) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shu X, Lev-Ram V, Deerinck TJ, Qi Y, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Jin Y, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. 2011. A genetically encoded tag for correlated light and electron microscopy of intact cells, tissues, and organisms. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001041 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001041) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giepmans BNG, Deerinck TJ, Smarr BL, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. 2005. Correlated light and electron microscopic imaging of multiple endogenous proteins using Quantum dots. Nat. Methods 2, 743–749. ( 10.1038/nmeth791) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karreman MA, Agronskaia AV, van Donselaar EG, Vocking K, Fereidouni F, Humbel BM, Verrips CT, Verkleij AJ, Gerritsen HC. 2012. Optimizing immuno-labeling for correlative fluorescence and electron microscopy on a single specimen. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 382–386. ( 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Micheva KD, Busse B, Weiler NC, O'Rourke N, Smith SJ. 2010. Single-synapse analysis of a diverse synapse population: proteomic imaging methods and markers. Neuron 68, 639–653. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikula S, Denk W. 2015. High-resolution whole-brain staining for electron microscopic circuit reconstruction. Nat. Methods 12, 541–546. ( 10.1038/nmeth.3361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharonov A, Hochstrasser RM. 2006. Wide-field subdiffraction imaging by accumulated binding of diffusing probes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18 911–18 916. ( 10.1073/pnas.0609643104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jungmann R, Steinhauer C, Scheible M, Kuzyk A, Tinnefeld P, Simmel FC. 2010. Single-molecule kinetics and super-resolution microscopy by fluorescence imaging of transient binding on DNA origami. NanoLett 10, 4756–4761. ( 10.1021/nl103427w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiuchi T, Higuchi M, Takamura A, Maruoka M, Watanabe N. 2015. Multitarget super-resolution microscopy with high-density labeling by exchangeable probes. Nat. Methods 12, 743–746. ( 10.1038/nmeth.3466) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen KH, Boettiger AN, Moffitt JR, Wang S, Zhuang X. 2015. Spatially resolved, highly multiplexed RNA profiling in single cells. Science 348, aaa6090. ( 10.1126/science.aaa6090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo SM, He J, Monnier N, Sun G, Wohland T, Bathe M. 2012. Bayesian approach to the analysis of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy data II: application to simulated and in vitro data. Anal. Chem. 84, 3880–3888. ( 10.1021/ac2034375) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo SM, Bag N, Mishra A, Wohland T, Bathe M. 2014. Bayesian total internal reflection fluorescence correlation spectroscopy reveals hIAPP-induced plasma membrane domain organization in live cells. Biophys. J. 106, 190–200. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.4458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monnier N, et al. 2015. Inferring transient particle transport dynamics in live cells. Nat. Methods 12, 838–840. ( 10.1038/nmeth.3483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Monnier N, Guo SM, Mori M, He J, Lenart P, Bathe M. 2012. Bayesian approach to MSD-based analysis of particle motion in live cells. Biophys. J. 103, 616–626. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. 2007. Intracellular amyloid-β in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 499–509. ( 10.1038/nrn2168) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halstead JM, Lionnet T, Wilbertz JH, Wippich F, Ephrussi A, Singer RH, Chao JA. 2015. Translation. An RNA biosensor for imaging the first round of translation from single cells to living animals. Science 347, 1367–1671. ( 10.1126/science.aaa3380) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jung H, Yoon BC, Holt CE. 2012. Axonal mRNA localization and local protein synthesis in nervous system assembly, maintenance and repair. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 308–324. ( 10.1038/nrn3210) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maness PF, Schachner M. 2007. Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 19–26. ( 10.1038/nn1827) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cordelieres FP, Bolte S. 2014. Experimenters’ guide to colocalization studies: finding a way through indicators and quantifiers, in practice. Methods Cell Biol. 123, 395–408. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-420138-5.00021-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Steensel B, van Binnendijk EP, Hornsby CD, van der Voort HT, Krozowski ZS, de Kloet ER, van Driel R. 1996. Partial colocalization of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in discrete compartments in nuclei of rat hippocampus neurons. J. Cell Sci. 109, 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G, Lockett S. 2004. Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein–protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys. J. 86, 3993–4003. ( 10.1529/biophysj.103.038422) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lagache T, Sauvonnet N, Danglot L, Olivo-Marin JC. 2015. Statistical analysis of molecule colocalization in bioimaging. Cytometry A 87, 568–579. ( 10.1002/cyto.a.22629) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conte WL, Kamishina H, Reep RL. 2009. Multiple neuroanatomical tract-tracing using fluorescent Alexa Fluor conjugates of cholera toxin subunit B in rats. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1157–1166. ( 10.1038/nprot.2009.93) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, Draft RW, Lu J, Bennis RA, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. 2007. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature 450, 56–62. ( 10.1038/nature06293) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Susaki EA, et al. 2014. Whole-brain imaging with single-cell resolution using chemical cocktails and computational analysis. Cell 157, 726–739. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cai D, Cohen KB, Luo T, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. 2013. Improved tools for the Brainbow toolbox. Nat. Methods 10, 540–547. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2450) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sholl DA. 1953. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J. Anat. 87, 387–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langhammer CG, Previtera ML, Sweet ES, Sran SS, Chen M, Firestein BL. 2010. Automated Sholl analysis of digitized neuronal morphology at multiple scales: whole cell Sholl analysis versus Sholl analysis of arbor subregions. Cytometry A 77, 1160–1168. ( 10.1002/cyto.a.20954) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Narayanan RT, Egger R, Johnson AS, Mansvelder HD, Sakmann B, de Kock CP, Oberlaender M. 2015. Beyond columnar organization: cell type- and target layer-specific principles of horizontal axon projection patterns in rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 25, 4450–4468. ( 10.1093/cercor/bhv053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oberlaender M, de Kock CP, Bruno RM, Ramirez A, Meyer HS, Dercksen VJ, Helmstaedter M, Sakmann B. 2012. Cell type-specific three-dimensional structure of thalamocortical circuits in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 22, 2375–2391. ( 10.1093/cercor/bhr317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Euler L. 1736. Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis. Commentarii Acad. Sci. Imperialis Petropolitanae 8, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Newman MEJ. 2010. Networks: an introduction, xi, p. 772 Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bullmore E, Sporns O. 2009. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 186–198. ( 10.1038/nrn2575) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. 1991. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 1, 1–47. ( 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scannell JW, Burns GA, Hilgetag CC, O'Neil MA, Young MP. 1999. The connectional organization of the cortico-thalamic system of the cat. Cereb. Cortex 9, 277–299. ( 10.1093/cercor/9.3.277) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Teller S, Granell C, De Domenico M, Soriano J, Gomez S, Arenas A. 2014. Emergence of assortative mixing between clusters of cultured neurons. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003796 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003796) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choe AS, Stepniewska I, Colvin DC, Ding Z, Anderson AW. 2012. Validation of diffusion tensor MRI in the central nervous system using light microscopy: quantitative comparison of fiber properties. NMR Biomed. 25, 900–908. ( 10.1002/nbm.1810) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang H, Zhu J, Reuter M, Vinke LN, Yendiki A, Boas DA, Fischl B, Akkin T. 2014. Cross-validation of serial optical coherence scanning and diffusion tensor imaging: a study on neural fiber maps in human medulla oblongata. Neuroimage 100, 395–404. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.032) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kraus D, Boyle V, Leibig N, Stark GB, Penna V. 2015. The neuro-spheroid: a novel 3D in vitro model for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. Methods 246, 97–105. ( 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.03.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin CA, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, Homfray T, Penninger JM, Jackson AP, Knoblich JA. 2013. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373–379. ( 10.1038/nature12517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi SH, et al. 2014. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 515, 274–278. ( 10.1038/nature13800) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chung K, et al. 2013. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497, 332–337. ( 10.1038/nature12107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richardson DS, Lichtman JW. 2015. Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell 162, 246–257. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reynaud EG, Krzic U, Greger K, Stelzer EH. 2008. Light sheet-based fluorescence microscopy: more dimensions, more photons, and less photodamage. HFSP J. 2, 266–275. ( 10.2976/1.2974980) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mertz J, Kim J. 2010. Scanning light-sheet microscopy in the whole mouse brain with HiLo background rejection. J. Biomed. Opt. 15, 016027 ( 10.1117/1.3324890) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dodt HU, Leischner U, Schierloh A, Jahrling N, Mauch CP, Deininger K, Deussing JM, Eder M, Zieglgansberger W, Becker K. 2007. Ultramicroscopy: three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain. Nat. Methods 4, 331–336. ( 10.1038/nmeth1036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pasca SP, Panagiotakos G, Dolmetsch RE. 2014. Generating human neurons in vitro and using them to understand neuropsychiatric disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 37, 479–501. ( 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen F, Tillberg PW, Boyden ES. 2015. Expansion microscopy. Science 347, 543–548. ( 10.1126/science.1260088) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]