Abstract

Purpose

In response to National Institutes of Health initiatives to improve translation of basic science discoveries we surveyed faculty to assess patterns of and barriers to translational research in Oklahoma.

Methods

An online survey was administered to University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, College of Medicine faculty, which included demographic and research questions.

Results

Responses were received from 126 faculty members (24%). Two-thirds spent ≥20% time on research; among these, 90% conduct clinical and translational research. Identifying funding; recruiting research staff and participants; preparing reports and agreements; and protecting research time were commonly perceived as at least moderate barriers to conducting research. While respondents largely collaborated within their discipline, clinical investigators were more likely than basic science investigators to engage in interdisciplinary research.

Conclusion

While engagement in translational research is common, specific barriers impact the research process. This could be improved through an expanded interdisciplinary collaboration and research support structure.

INTRODUCTION

In 2005, the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr. Elias Zerhouni, pointed out the need for a “new vision” for biomedical research that aims to improve the translation of basic science discoveries to testing in clinical trials and disseminating and implementing clinical trial findings to community and public health practice1. Basically, it was proposed that we needed to enhance the movement of basic bench research discoveries into directed patient care at a more rapid rate. This led to the initiation of Clinical and Translational Science Awards in 2006, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative to support interdisciplinary research and training programs with the mission of improving clinical and translational research at academic medical centers throughout the country. As a first step in building and enhancing interdisciplinary clinical and translational research programs in Oklahoma, an assessment of the current patterns of interdisciplinary and translational research is required to identify and eliminate barriers to the important translational (i.e., bench to bedside) research progression.

Weston et al. reported findings from a survey conducted in 2008–2009 at the Johns Hopkins University to determine the prevalence of translational and interdisciplinary collaboration at their institution2. Among respondents with more than 30% of their time committed to research, nearly 70% reported involvement in some form of interdisciplinary translational research, with early stage translation reported by nearly 80% of those involved in translational research with a smaller percentage reporting involvement in late stage translation (36%) or reverse translational research (36%). Several barriers to translational research were identified in this study, including complex regulatory requirements (54%), under-recognition of an individual’s contribution (42%), and a perceived lesser amount of funding for translational research (35%). Interdisciplinary collaborations were common with 47% of basic scientists collaborating with clinical investigators in the last year and 56% of clinical investigators collaborating with basic scientists2.

Relative to Johns Hopkins University, the College of Medicine at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center is smaller in size (911 versus 2824 faculty) and has a smaller scope of NIH funding with $34 million [$37,775 per capita] versus $433 million [$153,363 per capita] in annual total dollars awarded from the National Institutes of Health in 2011, respectively3. Given the disparity in size and overall NIH research funding level, the interdisciplinary and translational research practices and beliefs or barriers among College of Medicine faculty at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center likely do not mirror those reported by the faculty at Johns Hopkins University.

The population of Oklahoma has serious issues with overall poor health rankings, poor outcomes with common diseases (such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and arthritis) and underserved populations who are disproportionately afflicted by chronic health conditions. According to the United Health Foundation, in 2013 Oklahoma ranked 44th among the United States in overall health, 45th in obesity among adults, 43rd in diabetes among adults, 39th in smoking, and 48th in cardiovascular deaths4. New programs are needed to provide clinical and translational research infrastructure which fosters clinically relevant discoveries, translates findings into improved public health in Oklahoma and launches the careers of junior investigators engaged in interdisciplinary clinical and translational research endeavors in our state.

In preparation for implementing new programs and initiatives to foster interdisciplinary clinical and translational research at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center campus, it is important to first assess the baseline beliefs and practices of faculty involved in research. Identification of current practices and perceived barriers to interdisciplinary and translational research will be important in identifying areas to target for new research support services and areas for new or enhanced program development. Also, assessment of baseline practices is essential information when evaluating the impact of new programs or initiatives on translational science initiatives. Therefore, to inform new program development and evaluation, we conducted a survey among College of Medicine faculty to assess patterns of and barriers to clinical and interdisciplinary research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This cross-sectional survey was administered to all faculty, fellows and residents of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, including both the Oklahoma City and the Tulsa campuses. This report reflects only the respondents who reported that they held faculty appointments at the Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor level within the College of Medicine. Although the survey was administered to faculty in other colleges at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, a total of only 62 responses from all other six colleges were received. Furthermore, 21 or fewer responses were received from any other college and therefore, given the small sample size from faculty outside of the College of Medicine, this report is limited to respondents with appointments in the College of Medicine, which is the college where well over 90% of total NIH funding is awarded for research on the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center campus. An online survey was created using SelectSurvey software that included questions relevant to the specific aims of the project. The survey was modeled closely after an online assessment created by investigators at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine2. An initial email invitation that included the survey link was sent on September 25, 2012 with four reminders sent over the next four weeks before the survey closed on October 22, 2012.

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center approved the procedures used in this study.

Data Coding

Types of translational research objectives were classified into 3 categories as defined by Weston and co-workers2. The first category, early translation (T1), was defined as any indication of the translation of basic discovery into mechanistic studies in cell lines or animals, the translation of mechanistic studies into initial human testing, or the translation of initial human testing into proof of efficacy (i.e., clinical trials). The second category, later translation (T2), was defined as any indication of the translation of proof of efficacy into proof of effectiveness in a usual care setting, improving access to care, reorganizing and coordinating systems of care, helping physicians and patients to change behavior and make more informed choices, providing reminders and point-of-care decision support tools, or strengthening the patient-clinician relationship. The third category, reverse translation (RT), was defined as the translation of clinical observations into studies that could be examined empirically through basic science research studies.

Respondents were asked about their level of agreement, based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree, for several statements related to translational research. Due to the small number of respondents in some categories, the responses were grouped into three categories as Agree, combining Strongly Agree and Agree responses, Unsure, or Disagree, combining Strongly Disagree and Disagree. Similarly, responses to barriers faced during the research process were dichotomized by combining Moderate, Significant and Insurmountable responses and combining Not At All and Slight responses.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including counts and percentages, were calculated to summarize the distribution of responses. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Responses were received from 126 faculty members who reported holding Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor titles in the College of Medicine at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, reflecting a response rate of 24% among the 528 faculty holding these titles during the survey period. The response rates were similar among the faculty ranks with 43/206 (21%) for Assistant, 31/138 (22%) for Associate, and 52/184 (28%) for Full Professors.

Respondent Characteristics

Among respondents, 64% were male (Table 1). Full Professors were slightly more common among the survey respondents with Assistant Professors comprising 34%, Associate Professors comprising 25%, and Full Professors comprising 41% of the respondents. The majority of respondents were either principal or co-principal investigators (85%), defined as those who had submitted any grants for funding as the principal or co-principal investigator or had submitted any manuscripts for publication as the lead, senior or corresponding author in the last year, or co-investigators (10%), defined as those who were not principal or co-principal investigators but had submitted grants for funding as a co-investigator or had submitted manuscripts for publication as a co-author in the last year. There was an equal representation of respondents with M.D. degrees (46%) or Ph.D. degrees (46%). More than 35% of respondents had applied for or received research funding for more than 10 years. Only 13% of respondents had never applied for research funding. Two-thirds of the respondents dedicated at least 20% of their time to research.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents (n=126)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex a | ||

| Female | 45 | 36 |

| Male | 80 | 64 |

| Rank | ||

| Assistant Professor | 43 | 34 |

| Associate Professor | 31 | 25 |

| Professor | 52 | 41 |

| Degree b | ||

| MD | 57 | 46 |

| PhD | 57 | 46 |

| MD/PhD | 10 | 8 |

| Role c | ||

| PI/Co-PI | 106 | 85 |

| Co-I | 12 | 10 |

| Neither | 6 | 5 |

| Number of years applied for or received research funding d | ||

| Never applied for funding | 16 | 13 |

| <2 | 25 | 20 |

| 2–5 | 22 | 18 |

| 6–10 | 17 | 14 |

| 11–15 | 10 | 8 |

| >15 | 35 | 28 |

| Research effort e, % of time | ||

| 0–19 | 41 | 33 |

| 20–49 | 23 | 19 |

| 40–59 | 12 | 10 |

| 60–79 | 26 | 21 |

| 80–100 | 21 | 17 |

| At least 20% research effort f | ||

| Yes | 82 | 67 |

| No | 41 | 33 |

Missing = 1

Missing = 2

Missing = 2

Missing = 1

Missing = 3

Missing = 3

Involvement in Translational Research

Among 82 respondents with at least 20% of their time spent on research, 91% (n=75) were involved in one or more types of translational research (Table 2). Among those, 84% (63/75) worked on early translational projects (T1), 40% (30/75) on later translational projects (T2) and 43% (32/75) worked on reverse translational projects.

Table 2.

Count (Percentage) of Investigators Reporting Involvement in Any T1, T2, Reverse Translation, or Any Translational Research by Respondent Characteristics. Only participants with at least 20% research effort were included (n=82).

| Category of Respondent | n (%) In Category | T1 a (n=63) | T2 b (n=30) | RT c (n=32) | T d (n=75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 59 (72) | 47 (80) | 21 (36) | 20 (34) | 54 (92) |

| Female | 23 (28) | 16 (70) | 9 (39) | 12 (52) | 21 (91) |

| Degree | |||||

| MD | 24 (29) | 15 (63) | 13 (54) | 10 (42) | 21 (88) |

| PhD | 50 (61) | 42 (84) | 14 (28) | 14 (28) | 46 (92) |

| MD/PhD | 8 (10) | 6 (75) | 3 (38) | 8 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Appointment Rank | |||||

| Assistant Professor | 26 (32) | 22 (85) | 6 (23) | 9 (35) | 23 (88) |

| Associate Professor | 19 (23) | 14 (74) | 9 (47) | 9 (47) | 18 (95) |

| Professor | 37 (45) | 27 (73) | 15 (41) | 14 (38) | 34 (92) |

| Primary focus of research | |||||

| Humans | 40 (50) | 26 (65) | 26 (65) | 14 (35) | 37 (93) |

| Animals | 21 (26) | 21 (100) | 1 (5) | 8 (38) | 21 (100) |

| Devices/instruments/methods | 1 (1) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Cell & Molecular Biology | 18 (23) | 15 (83) | 2 (11) | 8 (44) | 15 (83) |

T1 indicates early translation: translation of basic discovery into mechanistic studies in cell lines or animals, the translation of mechanistic studies into initial human testing, or the translation of initial human testing into proof of efficacy (clinical trials).

T2, later translation: translation of proof of efficacy into proof of effectiveness in a usual care setting, improving access to care, reorganizing and coordinating systems of care, helping physicians and patients to change behavior and make more informed choices, providing reminders and point-of-care decision support tools, or strengthening the patient-clinician relationship.

RT, reverse translation: translation of clinical observations to basic research.

T, any translational research.

Gender does not influence the overall translational research percentage (92% and 91% of males and females reported involvement in some type of translational research activity, respectively). However, female researchers tended to focus on T1 and reverse translation, while male researchers focused more commonly on T1 translation. All respondents holding dual M.D./Ph.D. degrees (8/8) reported participating in translational research, particularly T1 and reverse translation. Early translational research involvement (T1) was more common than later (T2) or reverse translational research for those with a primary focus on animal studies or cellular and molecular biology studies while those focusing on human studies were equally involved in early (T1) and later (T2) translation.

Faculty Attitudes and Perceived Barriers to Conducting Translational Research

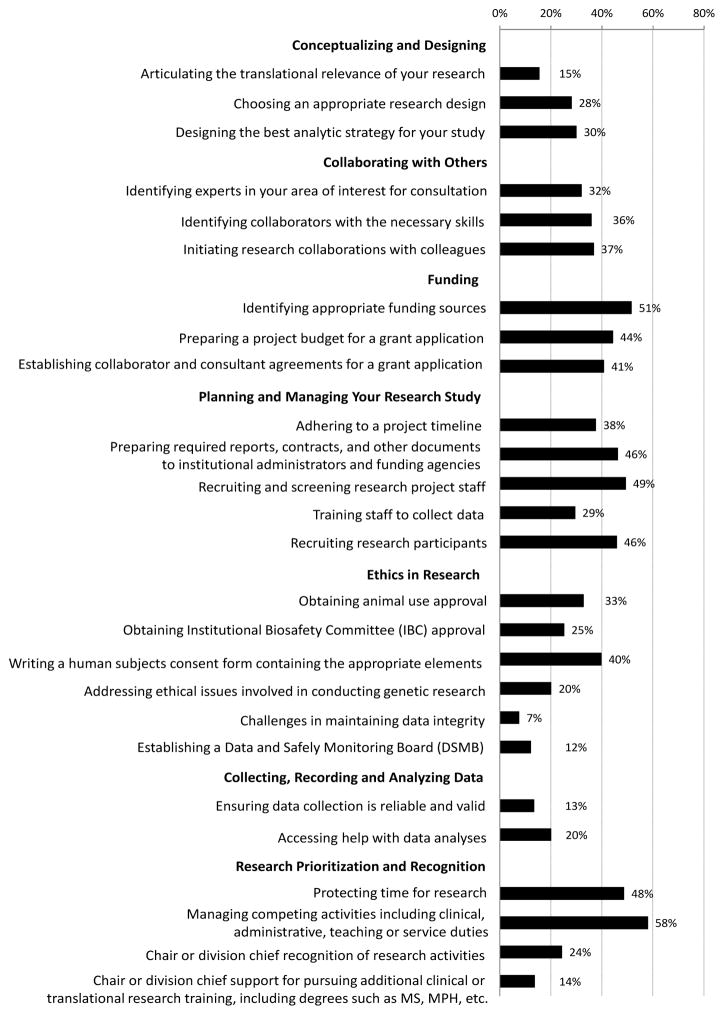

When considering the research process, from conceptualizing a study to analyzing the results, respondents commonly faced at least moderate barriers to various steps in the research process (Figure 1). Among respondents with at least 20% research effort who served as a principal or co-principal investigator during the last year, more than 40% reported facing at least moderate barriers to funding, including identifying appropriate funding sources (51%), preparing a project budget for a grant application (44%), and establishing collaborator and consultant agreements for a grant application (41%). Respondents also reported moderate or more significant barriers to aspects of planning and managing a research study, including preparing and submitting required reports, agreements, and other documents to institutional administrators and funding agencies (46%); recruiting and screening research project staff (49%); and recruiting research participants (46%). Finally, respondents faced at least moderate barriers to protecting time for research (48%) and managing competing professional activities (58%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of investigators who faced at least moderate barriers to various steps in the research process. Only respondents who served as the principal or co-principal investigator with at least 20% research effort were included (n=72).

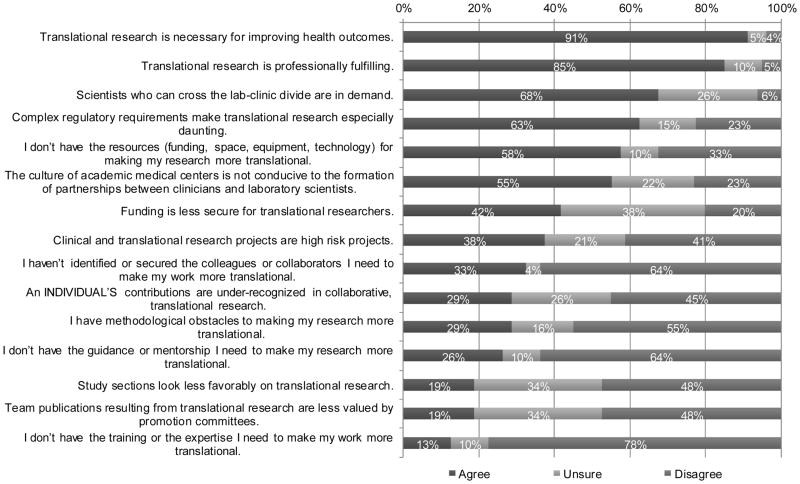

While a majority of respondents with at least 20% research effort disagreed that lack of guidance/mentorship, collaborators, training/expertise, and methodological obstacles were concerns of performing translational research on the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center campus (64%, 64%, 78%, and 55%, respectively disagreed); they did commonly agreed that not having resources (including funding, space, equipment and technology) for making their research more translational (58%) was an important issue (Figure 2). In addition, complex regulatory requirements and the culture of academic medical centers, not being conducive to the formation of partnerships between clinicians and laboratory scientists, were also indicated as potential barriers to enhancing translational research efforts in their research programs by more than half of the researchers responding (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Investigators’ attitudes about translational research. Only participants with at least 20% research effort were included (n=82).

A closer examination of the responses displayed in Figure 2 regarding faculty attitudes about translational research among respondents, who were grouped according to their level of agreement with the statement “The culture of academic medical centers is not conducive to the formation of partnerships between clinicians and laboratory scientists”, revealed more insight. Compared to respondents who did not report a concern to this statement (n=18), those who specifically agreed that the academic medical center culture was not conducive to the formation of partnerships (n=45) also more commonly agreed with the additional statements that “funding is less secure for translational researchers” (55% vs. 33% agreed), that “complex regularity requirements make translational research especially daunting” (79% vs. 61% agreed), and that they “haven’t identified or secured the colleagues or collaborators I need to make my work more translational” (37% vs. 22% agreed). Furthermore, those who specifically agreed that the academic medical center culture was not conducive to the formation of partnerships were less likely to agree that scientists who can cross the lab-clinic divide are in demand (67% vs. 83%) and were less likely to report methodological obstacles to making their research more translational (26% vs. 44%) compared to those who specifically disagreed with the statement that “the culture of academic medical centers is not conducive to the formation of partnerships between clinicians and laboratory scientists”. Finally, respondents with concerns related to the overall medical center culture as it relates to translational research were less likely to disagree with the statement that “team publications resulting from translational research are less valued by promotion committees” compared to those without concerns related to the academic medical center culture (40% vs. 61% disagreed).

Most respondents agreed that translational research is necessary for improving health outcomes and is professionally fulfilling. More than two-thirds also indicated that scientists who can cross the lab-clinic divide are in demand. There was a large amount of uncertainty, however, among respondents regarding how secure funding is for translational research projects, the level of recognition of an individual’s contribution in collaborative translational research, the degree of favorable perceptions for translational research by grant review study sections, the value of team publications resulting from translational research in terms of promotion review, and the demand for scientists who can cross the lab-clinic divide, with more than 25% of respondents indicating that they were unsure about these issues (Figure 2).

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

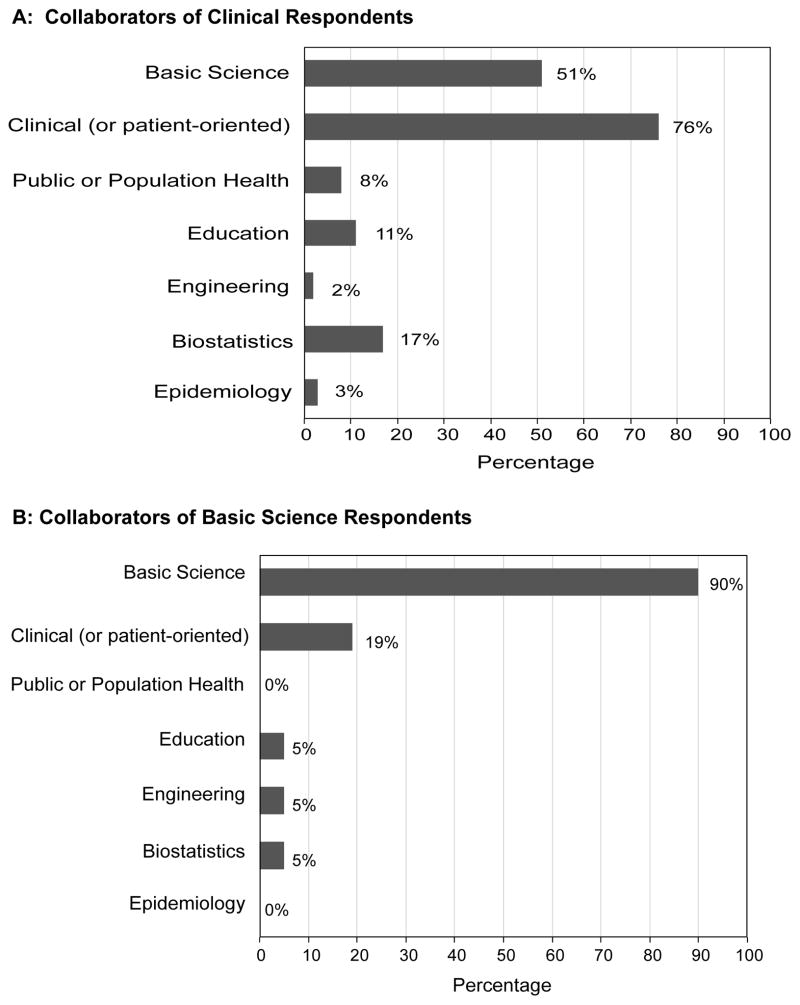

Among respondents with an appointment in a clinical department, 65% (63/96) reported having at least one collaborative research relationship compared to 75% (21/28) among respondents with an appointment in a basic science research department. While respondents tended to collaborate with other researchers from the same discipline (basic science: 90%, clinical: 76%), clinical investigators were more likely than basic science investigators to collaborate with basic or clinical investigators outside their discipline, respectively (51% vs. 19%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of collaborators by research type, limited to those who indicated at least one collaborative relationship. Sample sizes were: Panel A: Clinical Department n=63/96 (65%); Panel B: Basic Science Department n=21/28 (75%).

DISCUSSION

The reported beliefs and practices of College of Medicine faculty regarding translational and interdisciplinary research provides a foundation and baseline assessment against which the impact of new research initiatives can be evaluated in the future. A majority of respondents dedicated at least one day per week towards research efforts and nearly all such researchers were involved in translational research with T1, or early translational research, reported as the most common type. Identifying appropriate funding sources, preparing reports and agreements, recruiting and screening research project staff, recruiting research participants, protecting time for research, and managing competing activities were listed as barriers with significant influence on inculcating more translational research into College of Medicine research endeavors. Most respondents agreed that translational research is necessary for improving health outcomes and is professionally fulfilling. There was a large amount of uncertainty, however, among respondents with regard to the recognition received for these types of team-based translational research projects and publications and the possibility of future funding opportunities for translational research. While respondents tended to collaborate with other researchers from the same discipline, clinicians were more likely than basic science faculty to collaborate with research investigators from other disciplines. Complex regulatory requirements and the culture of academic medical centers were also noted as two impediments to increasing translational research and formation of partnerships between clinician researchers and laboratory bench scientists in the College of Medicine.

Our findings were similar to those reported at the much larger academic medical center of Johns Hopkins University in which 72% of respondents from their School of Medicine devoting more than 30% time to research reported involvement in some type of translational research, with early translation reported as the most common type (60%)2. However, when compared to the Johns Hopkins University report, College of Medicine faculty in Oklahoma were less likely to agree that an individual’s contributions are under-recognized in collaborative, translational research (29% vs. 42%, respectively), that team publications resulting from translational research are less valued by promotion committees (19% vs. 33%, respectively), and that grant review study sections look less favorably on translational research (19% vs. 26%, respectively). At the same time, College of Medicine faculty in Oklahoma were more likely to agree that the culture of academic medical centers is not conducive to formation of partnerships between clinicians and laboratory scientists compared to faculty from the Johns Hopkins University (55% vs. 33%, respectively). Similar to our findings, Weston et al. reported that respondents from Johns Hopkins tended to collaborate with other researchers from the same discipline (basic science: 93%, clinical: 91%). Clinical investigator collaborations were similar between the institutional cohorts, with 56% of clinical investigators collaborating with basic scientists at Johns Hopkins compared to 51% in the current study from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, but basic scientists in our cohort were less likely to collaborate with clinical faculty (19% vs. 47%). Differences between our results and those reported by Weston et al. should be interpreted cautiously because the Johns Hopkins University analysis results reflect respondents who devoted more than 30% time to research, versus at least 20% protected time for research among our cohort, and the prior study reflected respondents from the School of Medicine faculty (78%) as well as the Public Health, Nursing, and Engineering colleges (22%)2. Additionally, our survey was conducted in the fall of 2012, approximately four years after the Johns Hopkins survey was conducted. These factors may account for differences that are seen between the institutional results.

The results of this project hold implications for ongoing research initiatives in Oklahoma. In September 2013, a $20.3 million federal grant from the National Institutes of Health was awarded to the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center that includes many partner institutions, including the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and numerous other institutions across the state of Oklahoma to create the Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources (OSCTR). This OSCTR grant award is aimed at supporting important clinical and translational research programs, core research support services, and faculty development and training in translational research methodology, implementation and dissemination. The OSCTR will provide opportunities for greater networking and collaboration among clinicians, basic scientists, population scientists, and public health practitioners through integrated training and mentoring programs as well as workshops, seminars, and grant funding opportunities. The development of research support services through the OSCTR in biostatistics, epidemiology, research design, informatics, regulatory requirements, and community outreach, in addition to clinical research personnel and facilities, will now allow research barriers identified by survey respondents to be directly addressed in future years. In addition, guidance from a research navigator and training in translational research methods will address concerns related to access to research support services and project initiation and implementation. The OSCTR will also foster discussions of the value of interdisciplinary research, and supporting team-based research projects, thereby addressing concerns raised by respondents related to the institutional culture and difficulties in forming partnerships between clinicians and laboratory scientists.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Strengths of this study include the use of a previously-tested survey instrument. Limitations of this study include small sample sizes and low response rate, which likely reflects the lack of a currently robust translational research culture in the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine. As a result, there is a possibility that the respondent views may not be reflective of the views of the entire College of Medicine faculty, resulting in non-response bias. Furthermore, insufficient responses were received from faculty outside the College of Medicine. Attitudes and practices of College of Medicine faculty may not represent the views of faculty in other colleges. Finally, various definitions and classifications of translational research have been proposed. The reported study utilized the definitions of early, later, and reverse translational research as defined by Weston et al.2. Response distributions may have differed if a different classification had been used, such as that proposed by Westfall, Mold and Fagnan5 that further classifies later translational research endeavors as the translation of proof of efficacy into proof of effectiveness in a usual care setting, into translation to patients, through guideline development, followed by translation to practice, through dissemination and implementation research.

CONCLUSION

While a large percentage of respondents were engaged in translational science research, barriers were perceived that likely impact the translational research process in Oklahoma, which may be improved through expanded interdisciplinary collaborations that will be instituted through the newly awarded OSCTR program from the NIH. Initiatives of the OSCTR will support important clinical and translational research programs, core research support services, and faculty development and training in research methodology, implementation and dissemination. Subsequent studies will investigate the impact of these OSCTR initiatives on the translational and interdisciplinary research practices and beliefs of medical center faculty.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences 1U54GM104938 and 8P20GM103447.

Biographies

First Name: Hanh Dung, BS (please note: 2-part first name), Last Name: Dao, Mailing address: 801 NE 13th Street, CHB 318, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, Telephone number: 405-271-2229, Fax number: 405-271-2068, hanhdung-dao@ouhsc.edu, School of graduation and year: Northern Arizona University, 2011, Specialty: Epidemiology, Current position: Graduate Student Research Assistant, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Title or practice as it relates to the manuscript: Master of Science Degree Program Candidate in Epidemiology; Collaborated with coauthors to analyze survey data; Wrote first draft of the manuscript

Name: Pravina Kota, MBA, MS, Mailing address: 801 NE 13th Street, CHB 309, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, Telephone number: 405-271-2229 x 48063, Fax number: 405-271-2068, Pravina-kota@ouhsc.edu, School of graduation and year: Osmania University, India, 2000; Oklahoma State University 2004, Specialty: Management Information Systems, Current position: Senior Systems Analyst, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Title or practice as it relates to the manuscript: Collaborated with co-authors to develop and administer online survey and write manuscript

Name: Judith A. James, MD, PhD, Mailing address: 825 NE 13th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, Telephone number: 405-271-4987, Fax number: 405-271-7063, jamesj@omrf.org, School and year of graduation: OUHSC – Ph.D. in 1993 and M.D. in 1994, Specialy: Internal Medicine/Rheumatology, Current Position: Associate Vice Provost of Clinical & Translational Science Professor of Medicine University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and Chair, Arthritis & Clinical Immunology Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Title or practice as it relates to the manuscript: Collaborated with co-authors to analyze data and write manuscript

Name: Julie Ann Stoner, PhD, Mailing address: 801 NE 13th Street, CHB 309, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, Telephone number: 405-271-2229 x 49480, Fax number: 405-271-2068, julie-stoner@ouhsc.edu, School of graduation and year: University of Washington, 2000, Specialty: Biostatistics, Current position: Professor and Chair, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Title or practice as it relates to the manuscript: Collaborated with co-authors to develop survey instrument, analyze survey data, and write manuscript

Name: Darrin Akins, PhD, Mailing address: 940 Stanton L. Young Blvd, BMSB1053, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, Telephone number: 405-271-2133 x 46640, Fax number: 405-271-3117, darrin-akins@ouhsc.edu, School of graduation and year: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 1995, Specialty: Infectious Diseases, Current position: Professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Associate Dean for Research, College of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Title or practice as it relates to the manuscript: Collaborated with co-authors to develop survey instrument, analyze survey data, and write manuscript

References

- Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science–time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston CM, Bass EB, Ford DE, et al. Faculty involvement in translational research and interdisciplinary collaboration at a US academic medical center. J Investig Med. 2010;58(6):770–776. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e3181e70a78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. [Accessed on May 14, 2014];Ranking of NIH Awards to Each Medical School on a Per Capita Basis. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2012/PerCapitaSchoolOfMedicine_2012.xls.

- United Health Foundation. [Accessed on May 14, 2014];America’s Health Rankings, 2013 Annual Report. http://www.americashealthrankings.org/

- Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based Research - “Blue Highways” on the NIH Roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]