Abstract

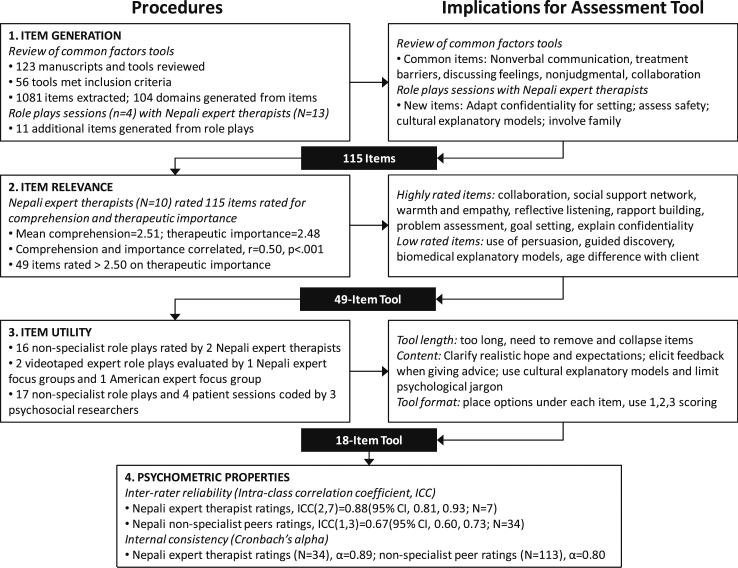

Lack of reliable and valid measures of therapist competence is a barrier to dissemination and implementation of psychological treatments in global mental health. We developed the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale for training and supervision across settings varied by culture and access to mental health resources. We employed a four-step process in Nepal: (1) Item generation: We extracted 1,081 items (grouped into 104 domains) from 56 existing tools; role-plays with Nepali therapists generated 11 additional domains. (2) Item relevance: From the 115 domains, Nepali therapists selected 49 domains of therapeutic importance and high comprehensibility. (3) Item utility: We piloted the ENACT scale through rating role-play videotapes, patient session transcripts, and live observations of primary care workers in trainings for psychological treatments and the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). (4) Inter-rater reliability was acceptable for experts (intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC(2,7)=0.88 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81—0.93), N=7) and non-specialists (ICC(1,3)=0.67 (95% CI 0.60—0.73), N=34). In sum, the ENACT scale is an 18-item assessment for common factors in psychological treatments, including task-sharing initiatives with non-specialists across cultural settings. Further research is needed to evaluate applications for therapy quality and association with patient outcomes.

Keywords: competence, culture, global health, measurement, psychotherapy, training

INTRODUCTION

Availability of evidence-based psychological treatment (PT) in low-resource settings is crucial to reduce the global burden of disease attributable to mental disorders (Fairburn & Patel, 2014). This requires task-sharing (WHO, 2008) which involves training non-specialists, such as individuals without professional mental health clinical degrees, to be competent in PT delivery.1 In both high and low resource settings, non-specialists can effectively deliver a range of PT (Montgomery, Kunik, Wilson, Stanley, & Weiss, 2010; van Ginneken et al., 2013). However, a lack of reliable and valid measures of therapist competence impedes the dissemination of evidence-based PT (Fairburn & Cooper, 2011; Muse & McManus, 2013; Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). Such measures are crucial to (1) interpret outcomes of effectiveness studies, (2) evaluate and refine training and supervision models, and (3) scale-up and disseminate PT in real-life context. Our goal was to develop a tool to evaluate competence in PT delivery across settings varied by culture and availability of professional resources.

Therapist competence is “the extent to which a therapist has the knowledge and skill required to deliver a treatment to the standard needed for it to achieve its expected effects,” (Fairburn & Cooper, 2011, p. 373). Therapist competence also should be reflected in therapy quality, which is “the extent to which a psychological treatment was delivered well enough for it to achieve its expected effects,” (p.373), and, ultimately, in patient outcomes. Variability in therapists’ training and competency may explain the lack of significant differences in some comparative treatment studies (Brown et al., 2013; Ehlers et al., 2010; Ginzburg et al., 2012). Because training and background of specialists and non-specialists may vary considerably, reliable and valid competence and quality assessment tools are crucial for global mental health research.

Miller's (1990) hierarchy of clinical skills includes 4 levels (Muse & McManus, 2013): Level 1 “knows” refers to conceptual knowledge of a PT and typically is assessed through multiple-choice questions. Level 2 “knows how” refers to knowledge of how to apply theory, which can be assessed through decision-making questions following clinical vignettes. Level 3 “shows” refers to competence in demonstrating the ability to apply skills, which can be assessed through role-plays with standardized patients. Level 4 “does” refers to how therapists apply skills in practice, which reflects therapist quality and is typically assessed through rating treatment sessions. Measurement of competence (Level 3, “shows”) is one of the least examined skill domains (Muse & McManus, 2013) and is especially lacking in training and research conducted in low- and middle-income counties (LMIC).

A major question in assessment of competence is what skills should be measured. Competence typically entails “limited domain intervention competence” (Barber, Sharpless, Klostermann, & McCarthy, 2007), which refers to specific practices for particular interventions, such as facilitating activation in cognitive behavior therapy. However, research has demonstrated that common factors in psychotherapy are vital for successful outcomes. Common factors have been categorized differently by scholars (Frank & Frank, 1991; Lambert & Bergin, 1994; Rosenzweig, 1936; Wampold, 2011): the main domains relate to therapist qualities and therapeutic alliance, mobilization of client and extra-contextual factors, promoting hope and expectancy of change, collaborative goal setting, ritualized procedures to work toward that goal, eliciting feedback, explanation for treatment grounded in a patient's belief system, and a healing setting.

In practice and research, it is difficult to disentangle common factors as distinct processes (Wampold, 2011). Common factors are interrelated, and they overlap with specific practice elements. A key distinction is that practice elements have a demonstrated evidence base for a specific patient population and typically are administered from selected manualized modules whereas common factors refer to those practices assumed to be universal for delivery of any effective PT (Barth et al., 2011). Therefore, if one is starting with non-specialists, they need to be competent in these common factors first before teaching them the required treatment-specific skills. Competency in common factors contributes to phenomena such as the “primary care paradox”, the observation that some conditions can be well treated by generalists despite delivery of manualized care that is of lesser technical proficiency (Stange & Ferrer, 2009). Unfortunately, common factors have received limited attention in LMICs (Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Nsereko, & de Jong, 2013; Kabura, Fleming, & Tobin, 2005) despite importance for care delivered by non-specialists.

Although tools to assess common factors are available in high-income countries (HICs), application of these tools are limited across settings varied by culture and professional resources. Barriers to applying these tools include experts required for scoring, narrow focus on content, reliance on patient feedback, length of tools, and high costs to administer some copyrighted tools. Moreover, although common factors are important across cultures (Frank & Frank, 1991; Othieno et al., 2013), instruments developed for use by educated professionals in HICs might overly represent values and treatment philosophies that are not associated with outcomes across cultures, such as an emphasis on biomedical models (Kleinman, 1988).

This study is part of a larger endeavor to improve mental healthcare in low resource settings (Lund et al., 2012) and to strengthen measurement of competence and quality for and by non-specialists in global mental health (c.f.,Singla et al., 2014). The focus of the current study is to develop a tool to assess competence in a manner that is not restrictive to HIC specialists and is relevant across cultural settings. We employ a four-part process to (1) collect a range of items related to common factors, (2) determine their face validity in a South Asian cultural context, (3) pilot the tool for feasibility and acceptability, and (4) establish psychometric properties. This is a systematic description of a procedure that can be replicated for developing common factors assessments across a range of interventions, provider disciplines, and cultural context.

METHODS

We developed this tool within a task-sharing initiative in a low-income, non-Western cultural setting. Nepal, a post-conflict country in South Asia with high prevalence of depression (Kohrt et al., 2012a) and suicide (Jordans et al., 2014), is participating in the Programme to Improve Mental Health Care (PRIME), an initiative in LMICs to develop mental health care in primary and community health settings (Jordans, Luitel, Tomlinson, & Komproe, 2013; Lund et al., 2012). In Nepal's Chitwan District, primary care and community health workers are being trained with a locally developed Mental Health Care Package (Jordans, Luitel, Pokharel, & Patel, in press), which includes the mental health Gap Action Programme—Intervention Guide (mhGAP-IG) (WHO, 2010), psychosocial skills modules, and brief modified versions of behavior activation (the Healthy Activity Program, HAP) and motivational interviewing (Counseling for Alcohol Program, CAP) from the Programme for Effective Mental Health Interventions in Under-resourced Health Systems (PREMIUM) (Patel et al., 2014; Singla et al., 2014). The Nepal Health Research Council approved the protocol.

Tool development included four steps: (1) generate common factors items; (2) determine cultural and clinical relevance of common factors items; (3) assess item utility through pilot application of the tool; and (4) establish psychometric properties. In the context of our study, ‘non-specialist’ refers to the primary care workers being trained in PT through PRIME. ‘Expert therapist’ refers to individuals who have completed a six-month training and have been practicing therapy for more than five years. Their six-month training course includes 400 hours of classroom learning, 150 hours of clinical supervision, 350 hours of practice, and 10 hours of personal therapy (Jordans, Tol, Sharma, & van Ommeren, 2003). All role-plays in the study were 15-20 minutes and covered a range of common patient presentations including depression, harmful drinking, sexual violence, other traumatic experiences, academic stressors, and self-harm. We generated role-plays based on actual patient interactions. Role-plays used with the common factors tool were designed for all items to be applicable. Expert therapists were trained to perform as standardized patients for all role-plays.

Step 1. Item Generation

To generate a pool of common factors items from which to develop a global mental health competence tool, we began by identifying patient-therapist interaction instruments used in HIC from a systematic review (Cahill et al., 2008). Instruments were included in our item generation procedure if they addressed at least two common factor domains from the established literature (Wampold, 2011). Instruments were excluded if they were limited to knowledge-only ratings; they were exclusive to rating couples, family, or children; items were limited to inner experiences of therapists or patients; or only psychodynamic concepts were included. Additional instruments were reviewed when identified through references of included publications. The goal was to generate a breadth of items rather than produce a list of representative frequency, which has been done previously for common factors (Grencavage & Norcross, 1990). A diversity of tools was coded including those related to cultural competence and manualized treatment assessment scales when they included common factors. We extracted and coded items from tools using QSR International's (2012) NVIVO 10. We grouped items into domains based on conceptual similarity.

In the second component of Step 1, 13 Nepali expert therapists participated in four role-play sessions with standardized patients to generate items. Each session consisted of two role-plays. After each role-play, we conducted semi-structured discussions about techniques and general practice. Prompts included, “What techniques did you recognize during the role-play?”, “What techniques have you used with similar patients?”, “When did you notice positive or negative reactions from the patient, and what was the therapist doing at that time?”, “In the role-play and your work, which therapist actions, behaviors, and techniques are most helpful to patients?” We generated additional common factor-related items from these sessions.

Step 2. Item Relevance

After items were generated, the next step was to score each item for comprehensibility, i.e., was a concept understandable for basic PT training, and importance, i.e., how important was the item in affecting therapeutic change. Ten Nepali expert therapists rated comprehension on a 1-to-3 scale: ‘1’ Concept is not clearly comprehensible in my experience and training. ‘2’ Concept is generally clear and comprehensible. ‘3’ Concept is very clear and I could explain it to my patients or therapy trainees. They rated importance for therapeutic change similarly: ‘1’ Concept is not usually essential for effective therapy in my experience. ‘2’ Concept is important sometimes in my therapy. ‘3’ Concept is important for all of patients. We selected items with high comprehension and therapeutic importance for piloting in the next step.

Step 3. Item Utility

The goal of the utility phase was to pilot the tool and evaluate the items and overall instrument for face validity (Did the items reflect practices assumed to be important for therapeutic change? Were important items missing?), feasibility (Was the behavior observable and was the format for scoring user-friendly?), and reliability (Did raters share a mutual understanding of ratings?). We evaluated these criteria qualitatively through pilot-testing and discussions with raters. Discussion prompts included “Which items were difficult to rate or unclear for scoring?”, “Which items were duplicates?”, “How did you distinguish among scores?”, “How user-friendly was the format?” In addition, we asked expert raters which common factors were the most in need of remediation among trainees performing role-plays.

In the first phase of piloting, two Nepali expert therapists used the tool to rate non-specialists conducting 15-minute role-plays after PRIME trainings. Each therapist rated eight non-specialist role-plays. After the role-plays, a focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted to qualitatively explore validity, feasibility, and reliability. Then five Nepali expert therapists rated two videotaped role-plays of Nepali expert therapists with standardized patients and participated in FGDs. Seven American psychiatrists with experience in psychotherapy training and research in global mental health viewed the Nepali videos (with English subtitles) and participated in a FGD.

Next, English language translations of Nepali audio recordings were qualitatively coded. The audio recordings included 27 non-specialist role-plays with standardized patients after PRIME trainings and four sessions of expert Nepali therapists with actual patients. Actual patient sessions were included to identify potential items not captured in role-plays. Transcripts were coded by three raters (one American graduate student, one Nepali psychosocial researcher, and one American psychiatrist with extensive experience working with Nepali patients) using the tool as the initial guide. We used NVIVO after establishing adequate coder inter-rater reliability (> 80% agreement). The goal of coding was to assess the same components as above: validity, feasibility (specifically regarding what could and could not be rated with transcripts), and reliability. We used the qualitative findings from Step 3 to revise, remove, add, and collapse items, and to reformat the tool.

Step 4. Psychometric properties

After developing an 18-item version of the tool, we assessed inter-rater reliability for expert therapists and non-specialists. Expert inter-rater reliability was assessed with Nepali therapists (N=7) who had not participated in prior phases of the research. They rated two 15-minute videotaped standardized patient sessions from which we calculated a one-way random effects model, average measures intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Non-specialists inter-rater reliability was calculated with 34 primary care health worker trainees completing the PRIME training. At the end of the training, each of the 34 trainees completed one 15-minute role-play with a standardized patient with depression. Each trainee took a turn performing the role-play in a group with 2 to 4 other non-specialist trainees observing and scoring the interaction. Each of the 34 role-plays was rated by 2 to 4 peers (mean=3.32 peers) totaling 113 peer ratings. We calculated a two-way random effects model, average measures ICC utilizing all peer ratings.

These trainee role-play peer ratings (N=113) also were used to calculate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of the scale among non-specialists. In addition, we calculated Cronbach's alpha for experts using Nepali therapists who provided one rating for each of the trainee role-plays (N=34).

RESULTS

Step 1. Item Generation

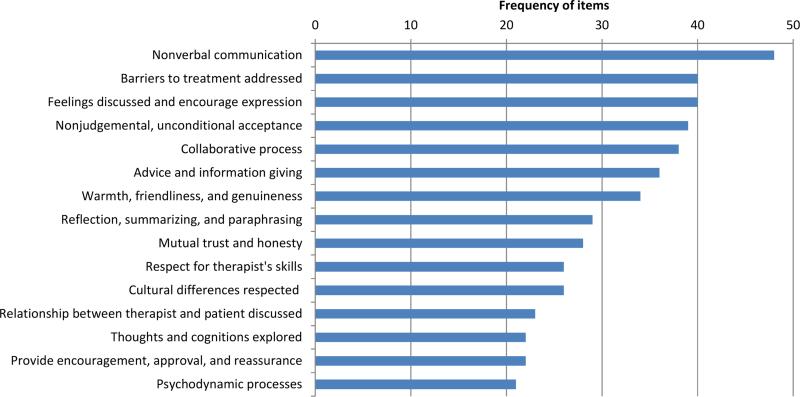

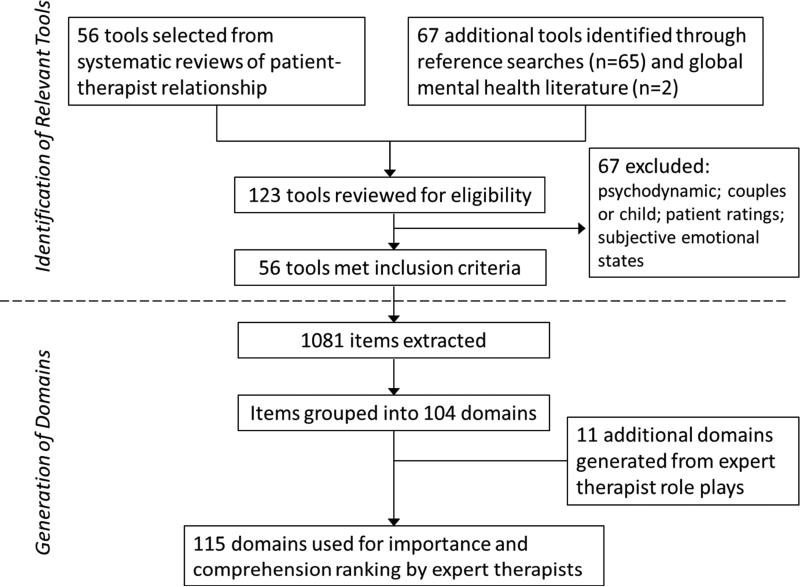

For selection of tools from which to extract items, we began with a systematic review of therapist-patient interaction assessments that included 56 tools (Cahill et al., 2008). Thirty-three of these tools qualified for item-specific extraction based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria. We identified an additional 65 tools from references for each of the 33 included tools; 21 of these 65 additional tools met inclusion criteria. One additional tool was included because it previously had been used to rate competence of common factors in a LMIC (Kabura et al., 2005). In addition, the mhGAP-IG was coded to identify common factors-related skills needed to implement task-sharing programs. In total, we reviewed 123 articles and included 56 tools (33 tools from the prior systematic review, 21 from references for these tools, and two from global mental health literature, see Supplemental File). We extracted 1,081 items from the 56 tools and grouped them into 104 domains based on conceptual similarity following approaches consistent with prior common factors reviews (Grencavage & Norcross, 1990). The top 15 domains accounted for 44% of the 1,081 items (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of items in top 15 domains among 1,081 items extracted from 56 common factors-related assessment tools

We identified additional themes from semi-structured role-plays and discussion sessions with Nepali therapists. Therapists prioritized assessment and management of patient safety. They discussed adapting confidentiality practices to the physical location of health encounters. They explained that primary care visits rarely are conducted in a confidential space. Another communication issue was the role of ethnicity, caste, gender, and age, which influenced the relationship between health workers and patients.

Therapists reported the importance of explaining therapy in culturally-appropriate idioms and concepts. Direct translations of psychological terminology related to cognitions and behavior was inadequate. Therapists employed Nepali concepts of man (heart-mind), dimaag (brain-mind), and their interconnection.2 In addition, therapists emphasized avoiding local stigmatizing idioms and biomedical jargon.

Eleven items were added based on these Nepali therapist role-plays and discussions (Figure 2). At the conclusion of Step 1, there were 104 literature-search generated items and 11 Nepali therapist generated items, totaling 115 items.

Figure 2.

Identification of relevant tools and generation of domains for Step 1 of tool development process

Step 2. Item Relevance

Nepali therapists who had not participated in the previous step rated the 115 items for comprehensibility and therapeutic importance. Comprehension and therapeutic importance were correlated (r=0.50, p<.001). Mean comprehension ranking was 2.51, and mean therapeutic importance was 2.48. Top rated items were collaboration, assessing social support, and warmth, friendliness, and respect. Among the lowest-rated items were use of persuasion and biomedical explanations of mental health involving neuroscience and genetics. In total, 49 items (43% of all items) had a therapeutic importance score greater than 2.50 and were selected for piloting. All items selected for piloting had a comprehension mean of 2.25 or greater (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comprehensibility and Therapeutic Importance for 49 Highest Ranked Items

| Item | Comprehensiona | Therapeutic Importanceb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Err. | Mean | Std. Err. | |

| 1. Collaboration between therapist and patient | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 2. Assessing patient's social support network | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 3. Warmth, friendliness, and respect toward patient | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 4. Empathic understanding of patient | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 5. Reflective listening | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 6. Rapport building with patient | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 7. Problem assessment and prioritization | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 8. Goal setting | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 9. Explaining confidentiality | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 10. Assessing patient's insight for key problem | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 11. Use of problem solving strategies | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 12. Identification of patient coping strategies | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 13. Making a plan of action for each session | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 14. Identification of patient's resources | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 15. Providing emotional support toward patient | 2.88 | 0.13 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 16. Nonverbal communication | 2.75 | 0.16 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 17. Praising patient's efforts | 2.75 | 0.16 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| 18. Develop therapy agenda for course of treatment | 3.00 | 0.00 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 19. Therapist's belief that treatment approach will help patient | 3.00 | 0.00 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 20. Assessing patient's strengths | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 21. Explaining how therapy works | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 22. Assessing patient's active help seeking | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 23. Discussing patient's explanation for difficulties (explanatory model) | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 24. Assessing patient's ability to develop multiple solutions to problems (pathways thinking) | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 25. Therapist's ability to flexibly employ different therapy techniques | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.88 | 0.13 |

| 26. Assessing patient's recent life events | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 27. Identification of appropriate location for confidentiality | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 28. Providing general psychoeducation | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 29. Operate within time-limited treatment frame and prepare for termination | 2.63 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 30. Therapist adjusts content of session to limitations of settings | 2.63 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 0.25 |

| 31. Patient's belief that therapy will address problem | 2.63 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 0.25 |

| 32. Patient leads in ranking goals | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 33. Pacing and efficient use of time | 2.50 | 0.19 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 34. Eliciting patient's feedback | 2.38 | 0.26 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 35. Develop trust and respect for therapist | 2.25 | 0.31 | 2.75 | 0.16 |

| 36. Use of specific family psychoeducation | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 37. Assessing and managing harm and safety | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 38. Assess patient's experience of empathy and feeling understood | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 39. Therapist exploration of patients experiences and feelings | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.63 | 0.26 |

| 40. Avoiding negative therapist attitude | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.63 | 0.26 |

| 41. Therapist exploring level of patient's family support | 2.75 | 0.16 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 42. Giving feedback | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 43. Assessing patient's level of functioning before treatment | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 44. Assessing patient's belief in self to solve problems (agency thinking) | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.63 | 0.26 |

| 45. Discussing patient's secure attachment relationships | 2.63 | 0.18 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 46. Assessing patient's personal motivation | 2.50 | 0.19 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 47. Building patient's hope | 2.50 | 0.19 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 48. Assessing patient's amount of hope | 2.50 | 0.19 | 2.63 | 0.18 |

| 49. Family's belief that therapy will help patient | 2.25 | 0.25 | 2.63 | 0.26 |

Comprehension of Items was rated on 1 to 3 scale: '1' Concept/process is not clearly comprehensible in my experience and training (for example, I have rarely heard this term or process discussed). '2' Concept is generally clear and comprehensible in my experience and training (for example, I have heard of this term or process, but I still have some questions about the term or process). '3' Concept is very clear and I could explain it to any of my patients/clients or to therapy trainees.

Importance for Therapeutic Change was rated on a 1 to 3 scale: '1' Concept/process is not usually essential for effective therapy in my experience. '2' Concept/process is important sometimes in my therapy and with some patients/clients. '3' Concept/process is important for all of my patients/clients.

Step 3. Item Utility and Scoring

We piloted the 49-item version of the tool with expert therapists rating non-specialist role-plays, experts rating videotaped role-plays, and researchers coding transcripts. Therapist feedback highlighted concerns about the length of the tool, i.e., 49-items could not be feasibly rated in brief sessions during live observation. In addition, discussions and transcription coding revealed a lack of clarity about scoring (e.g., item redundancy, items representing different skill levels of a single process). Therefore, we reduced the number of items from 49 to 18 through three main processes: elimination of items, grouping items into a single category, and using items to indicate different skill levels within the same domain.

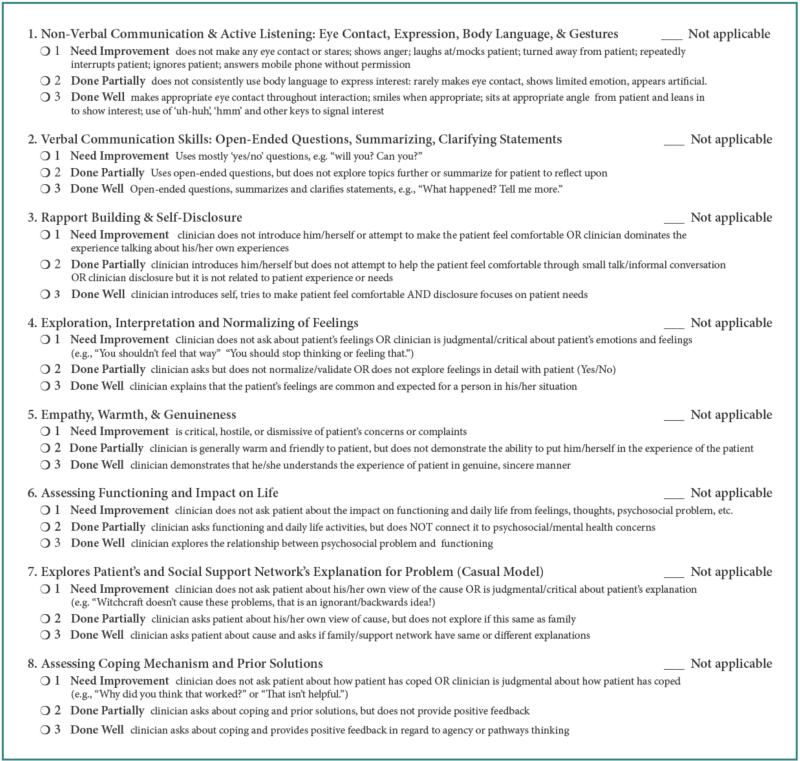

The final version of the tool (Figure 3) included nine items that were common in HIC instruments: non-verbal and verbal communication (Items #1 and 2), collaborative processes (Item #12), rapport and self-disclosure (Item #3), interpretation of feelings (Item #4), empathy (Item #5), encouragement and praise (Item #8), exploring the relationship between life events and mental health (Item #9), and problem solving (Item #15).

Figure 3a.

ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale, page 1

Nine items on the final tool required significant adaptation to address task-sharing and cultural context: Explanatory models (Items #7 and 14) were deemed crucial for success of PT in this South Asian cultural setting and could be scored easily through observations and transcript ratings. Eliciting explanatory models was important given the low relevance of biomedical explanatory models in therapist ratings. Assessing functional impairment (#6) was prioritized to raise awareness among patients about the relationship between mental health and daily activities, which was important to mobilize participation in care for patients and families.

Promoting realistic hope and expectancy of change (Item #13) was included because many non-specialists trainees created unrealistic expectations of what PT could accomplish. Nepali therapists reported difficulty when teaching non-specialists to explain PT and foster feasible expectations. American psychiatrists underscored the need for realistic expectations when working with populations unfamiliar with psychotherapy. Non-specialists typically lectured patients without assessing their understanding of diagnoses and treatment. Therefore, we combined eliciting feedback with providing advice (Item #16).

In Nepali and American focus groups, therapists prioritized working with families (Item #11) as a crucial skill in cross-cultural context. An area for improvement was over emphasis on speaking with family members to the neglect of patient concerns. Involvement of families also influenced confidentiality practices (Item #17).

The need to do holistic health assessments (Item #10) including suicide screening (Item #18) was important for low resource settings where non-specialists may make diagnoses, manage mental and physical health issues, and be the only health workers available to address psychiatric emergencies (c.f., WHO, 2010).

Based on piloting, we changed scoring options. Initially, the three scoring levels were 0 ‘not at all’, 1 ‘minimal use’, and 2 ‘effective use’. After working with non-specialist and expert raters, we changed the scoring options to 1-2-3, with 1 ‘needs improvement’, 2 ‘done partially’, and 3 ‘done well’. We chose these responses because scores of ‘0’ and terms such as ‘not done’ or ‘inappropriate’ were socially awkward for non-specialists to endorse when rating peers in Nepali culture. By eliminating ‘0’ respondents said they felt more comfortable endorsing the lowest value on the tool. This facilitated an environment for peers to engage in quality improvement and led to a greater range on item responses.

Step 4. Psychometric Properties

Expert ICC (2,7) based on therapists rating videotapes was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81—0.93). Non-specialist peer ICC (1,3) based on post-training role-plays was 0.67 (95% CI 0.60—0.73). Cronbach's alpha based on 34 expert ratings of non-specialist roles plays was 0.89. Cronbach's alpha for non-specialist peer-ratings was 0.80 (N=113).

DISCUSSION

The ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT)3 rating scale was developed to facilitate rating therapist competence. We employed a systematic process to generate items, evaluate relevance and utility, and calculate basic psychometric properties (Figure 4). The tool demonstrated good psychometric properties. Nine of the items in the final tool were commonly included in HIC tools: non-verbal and verbal communication (Items #1 and 2), collaborative processes (Item #12), rapport and self-disclosure (Item #3), interpretation of feelings (Item #4), empathy (Item #5), encouragement and praise (Item #8), exploring the relationship between life events and mental health (Item #9), and problem solving (Item #15).

Figure 4.

Four-step systematic process of development for the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale

The other half of the items captured features relevant for cross-cultural task-sharing initiatives. Culturally-specific additions included assessment of the patient's and family's explanatory models (Item #7) and explaining psychological therapies and mental health treatment (Item #14). Explanatory models include perceptions of symptoms, etiology, and treatment seeking behaviors. Use of explanatory models and ethnopsychology (local psychological concepts) is a crucial aspect of adapting PT across cultural settings (Hinton, Hofmann, Pollack, & Otto, 2009; Kohrt et al., 2012b). A recent meta-analysis of cultural adaptation of PT found that use of explanatory models, also known as “illness myths”, was the sole moderator of superior outcomes for culturally-adapted therapies (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011).

Promoting hope and expectancy of change (Item #13) is a common factor for effective treatment (Snyder & Taylor, 2000). Cross-cultural family therapy research and medical anthropology studies have highlighted the crucial need for hope to be reasonable and realistic, especially in context of endemic poverty and political violence (Eggerman & Panter-Brick, 2010; Weingarten, 2010), otherwise providers risk raising expectations leading to demoralization among patients and therapists when rapid gains are not achieved (Griffith & Dsouza, 2012).

An area not commonly evaluated in HIC instruments was assessment of daily functioning and its association with mental health (Item #6). In cross-cultural mental health, assessment of functioning is important to avoid the “category fallacy” in which psychiatric symptoms are assumed to have the same meaning and life impact regardless of cultural context (Kleinman, 1988).

We included item #11 to support skill development toward appropriate family involvement because therapists reported the importance of family for successful treatment, and it was a skill poorly executed by most non-specialists. We included confidentiality (Item #17) because of the settings for PT in LMIC (e.g., lack of individual consultation rooms, conducting therapy in outdoor settings). We included providing advice with eliciting feedback (Item #16) because of the tendency to lecture patients and family members without eliciting their understanding of problems and treatment.

Holistic health assessment (Item #10) and assessment of suicidal behavior and safety (Item #18) were included because these responsibilities fall on non-specialists as incorporated in the mhGAP-IG. Safety assessment was of particular importance given the evidence for suicidality screening as an effective prevention strategy (Mann et al., 2005) and high prevalence of suicide in South Asia (Jordans et al., 2014).

Limitations

Assessment of therapist competence has a range of challenges (Muse & McManus, 2013), especially in LMIC task-sharing initiatives which have a small, but growing, research foundation (van Ginneken et al., 2013). Our approach has limitations to consider when applying the tool across settings. First, we chose to employ an item generation process that focused on a breadth of potential common factors rather than a systematic review to assess frequency among all extant tools, which has been done previously for common factors (Grencavage & Norcross, 1990) and CBT tools (Muse & McManus, 2013). The overlap of our domains with these reviews suggests that we captured the majority of key domains. Another challenge was the coding process which suffers from the same limitations as pointed out in prior reviews (Grencavage & Norcross, 1990): specifically, how items are grouped varies based on one's discipline and training.

Given the lack of studies on relative contribution of different common factors and treatment specific factors on patient outcomes in LMIC task-sharing studies, there were not databases available with information on patient outcomes to compare with common factor competency of non-specialists. Therefore, reliance on expert Nepali therapists’ subjective appraisal of what they perceive is effective in psychological treatments was a pragmatic first step. There is potential inconsistency between what therapists perceive to be effective and what actually benefits patients. A convergent finding of our process was Nepali therapists’ inclusion of common factors domains that have shown effectiveness in prior studies and meta-analyses (Wampold, 2011). Future studies in PRIME will compare common factors items with patient outcomes to further refine the skills to be evaluated and promoted in task-sharing interventions.

Compared to knowledge-based measures of competence such as multiple-choice questionnaires, a limitation inherent in our approach is the requirement for subjective observer ratings. Usefulness of the tool is dependent upon the ability of non-specialists to make ratings. A hopeful development is that ratings of therapy quality by non-specialists approached those of experts over successive applications in PREMIUM (Singla et al., 2014). In addition, non-specialist peer ratings collected in groups allow for averaging among non-specialist raters, thus reducing the impact of single raters poorly applying the tool. Group peer ratings also increase the potential for the tool to foster feedback and learning.

Regarding psychometric properties established during tool development, the ICC for non-specialist peer-raters was 0.67. This was comparable to the ICC achieved for non-specialist peer-raters scoring general skills in PREMIUM, ICC=0.62 (Singla et al., 2014). Supervision provides an important opportunity to improve understanding of common factors, and ICC for non-specialist peer-raters may improve during the supervision process.

This common factors tool does not supplant the need for evaluation of treatment-specific and phase-specific components of evidence-based interventions. Our goal was to address the gap in instrumentation for common factors across types of interventions in global mental health research. Practitioners will gain a greater understanding of mechanisms in PT and skill levels needed for dissemination through a combination of treatment-specific tools and culturally-appropriate, systematically-developed common factors tools. Ultimately, assessing patient outcomes against both treatment specific and common factors competencies can help inform evidence-based trainings and dissemination efforts.

Applications

We designed the tool for multiple applications: training evaluations and supervision; selecting trainers, supervisors, and research supervisors; and monitoring common factors in interventions to compare with patient outcomes (Table 2). Innovative protocols can be used to explore novel supervision and training approaches. For example, video and audio recordings of role-plays with standardized patients can be shared over the internet to conduct ratings in a crowdsourcing platform (Fairburn & Patel, 2014). More research also is required in other cultural context. In other settings, an abbreviated adaptation process could begin by producing videos of role-plays for specific interventions and conducting workshops with intervention experts to view and rate the videos with the ENACT scale translated into the local language. Then the tool could be piloted with the target providers, further modified, and applied to determine psychometric properties. Because the collaborative therapeutic alliance is the most frequent commonality in therapeutic engagement (Grencavage & Norcross, 1990), this tool also has potential for mental health applications beyond PT. Patients in primary care would benefit from provider competency in common factors even if treatment were not a manualized PT.

Table 2.

Application of the Enhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale for global mental health research and implementation

| Competence Rating Periods | Objectives of Competence Rating | Sources for Ratings | Raters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training evaluation |

Trainee evaluation: Post-training evaluations of trainees with standardized role plays to certify individual trainees meeting minimum competence level; Training effectiveness evaluation: Pre- and post-measures of trainees to assess effectiveness of training curriculum and trainer to improve trainee competence |

Modality: Standardized patient role plays; Group training exercises (role plays) Formats: Live observations, video recordings, audio recordings, transcripts |

Trainers with some mental health expertise; Peer trainees without mental health expertise; External raters with mental health expertise |

| Clinical supervision | Health worker skill improvement: Standardized role plays could be used periodically in supervision and rated to assess maintenance and improvement of competence over time. |

Modality: Standardized patient role plays; Formats: Live observations, video recordings, audio recordings, transcripts |

Non-specialist peers after completion of task-sharing training; Supervisors including peers or mental health experts; External raters with mental health expertise |

| Selection for training or intervention |

Primary selection: Selection of non-specialist health workers to participate in training to deliver mental health services; Secondary selection: Selection of non-specialist health workers with prior experience to become trainers, supervisors, or to participate in intervention trials |

Modality: Standardized patient role plays Formats: Live observations in clinical settings, video recordings, audio recordings, transcripts |

Primary selection: Trainers with mental health expertise Secondary selection: Trainers or clinical managers with mental health expertise |

| Intervention trials | Competence throughout trial period: As a complement to traditional measures of fidelity, competence can be assessed at intervals during trials to measure maintenance or drift in skills |

Modality: Periodic role plays Formats: Video recordings, audio recordings, transcripts |

External raters with mental health expertise |

CONCLUSION

Competent specialist and non-specialist therapists are needed to increase availability of effective psychological treatment. Current training programs and research trials are limited by the lack of competence assessment tools that can be easily administered across a range of cultural settings and intervention programs. We developed the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) scale to meet these needs with core applications including training and supervision; selecting trainees, trainers, and supervisors; and monitoring intervention trials. Continued development and application is required to determine the cross-cultural and cross-intervention utility, association with therapy quality, and validity for predicting patient outcomes. Only through development of such tools will we be able to measure accurately what works and how best to disseminate and implement psychological treatment to meet the needs of diverse populations throughout the world.

Supplementary Material

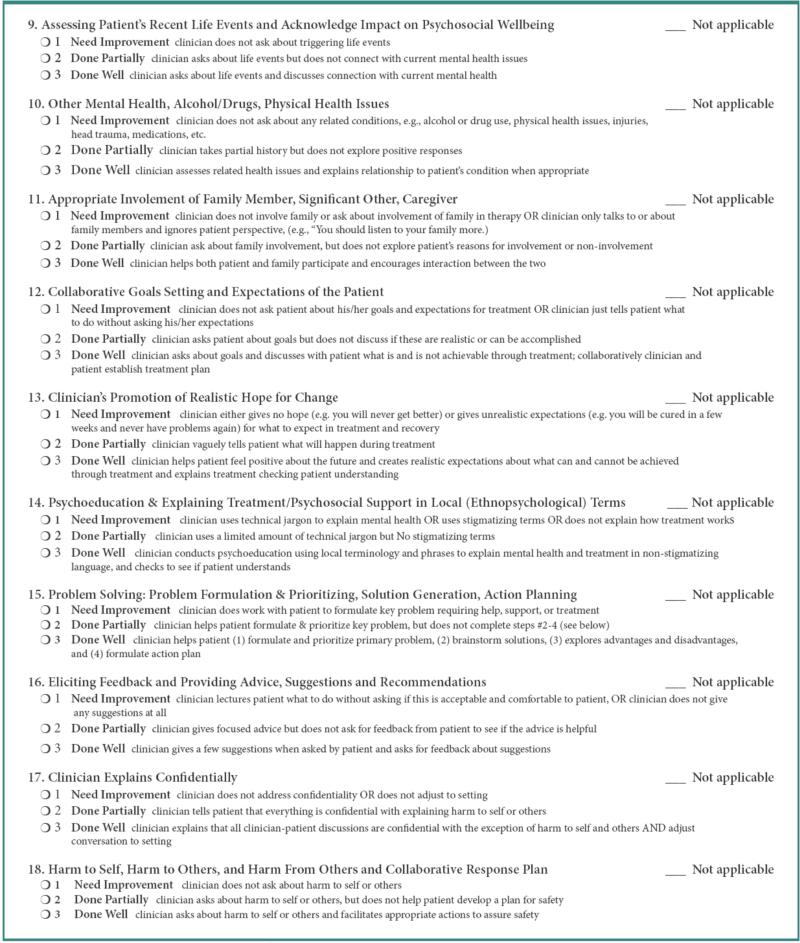

Figure 3b.

ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale, page 2

Highlights.

We review and assess cultural relevance of common factors rating tools

We develop and pilot a novel tool to assess competence in global mental health

The tool demonstrates good psychometric properties when used by non-specialists

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was conducted through the South Asia Hub for Advocacy, Research, and Education for Mental Health (SHARE) funded by NIMH (U19MH095687-01S1, PIs: Vikram Patel and Atif Rahman), the Programme to Improve Mental Health Care (PRIME, PI: Crick Lund) funded by the Department for International Development (DfID), and Reducing Barriers to Mental Health Task Sharing (K01 MH104310-01, PI: Brandon Kohrt). This document is an output from the PRIME Research Programme Consortium, funded by the UK Department of International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors had full control of all primary data. Vikram Patel is funded by the Wellcome Trust and the NIMH grant to SHARE. The authors thank Matthew Burkey, Michael Compton, James Griffith, Revathi Krishna, Crick Lund, and Lawrence Wissow for their valuable discussions during the tool development process. Special thanks for Lawrence Wissow and Matthew Burkey for their comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Task-sharing, also known as task-shifting, refers the involvement of non-specialist service providers to collaborate in delivery of healthcare services traditionally relegated to experts with professional degrees or certification (WHO, 2008). In the context of global mental health, ‘non-specialist’ refers to a person who lacks specialized professional training in fields such as psychology, psychiatry, or clinical social work. Non-specialists in both low- and high-resource settings may include community health volunteers, peer helpers, social workers, midwives, auxiliary health staff, teachers, primary care workers, and persons without a professional service role.

The concept of man (heart-mind) refers to the organ of emotion and memory, whereas dimaag (brain-mind) refers to cognition and social regulation of behavior (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). These concepts have been used in cultural adaptation of cognitive behavior therapy and other psychological treatments in Nepal and for ethnic Nepali Bhutanese refugees (Kohrt, Maharjan, Timsina, & Griffith, 2012b).

This tool has been previously presented as the Training and Supervision Common Therapeutic Factors Rating (TASC-R) Scale (Kohrt, 2014).

REFERENCES

- Barber JP, Sharpless BA, Klostermann S, McCarthy KS. Assessing intervention competence and its relation to therapy outcome: A selected review derived from the outcome literature. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38(5):493. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Lee BR, Lindsey MA, Collins KS, Strieder F, Chorpita BF, Sparks JA. Evidence-based practice at a crossroads: The emergence of common elements and factors. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011:1049731511408440. [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: a direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(3):279–289. doi: 10.1037/a0023626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Craske MG, Glenn DE, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Rose RD. CBT competence in novice therapists improves anxiety outcomes. Depression & Anxiety. 2013;30(2):97–115. doi: 10.1002/da.22027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill J, Barkham M, Hardy G, Gilbody S, Richards D, Bower P, Connell J. A review and critical appraisal of measures of therapist-patient interactions in mental health settings. Health Technology Assessment. 2008;12(24):iii, ix–47. doi: 10.3310/hta12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggerman M, Panter-Brick C. Suffering, hope, and entrapment: Resilience and cultural values in Afghanistan. Social Science & Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Bisson J, Clark DM, Creamer M, Pilling S, Richards D, Yule W. Do all psychological treatments really work the same in posttraumatic stress disorder? Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Therapist competence, therapy quality, and therapist training. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(6):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Patel V. The Global Dissemination of Psychological Treatments: A Road Map for Research and Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(5):495–498. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13111546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JD, Frank JB. Persuasion and Healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. Third ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg DM, Bohn C, Hofling V, Weck F, Clark DM, Stangier U. Treatment specific competence predicts outcome in cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2012;50(12):747–752. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grencavage LM, Norcross JC. Where are the commonalities among the therapeutic common factors? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1990;21(5):372. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JL, Dsouza A. Demoralization and hope in clinical psychiatry and psychotherapy. In: Alarcon RD, Frank JB, editors. The Psychotherapy of Hope: The Legacy of Persuasion and Healing. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2012. pp. 158–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Otto MW. Mechanisms of Efficacy of CBT for Cambodian Refugees with PTSD: Improvement in Emotion Regulation and Orthostatic Blood Pressure Response. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2009;15(3):255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans M, Luitel N, Tomlinson M, Komproe I. Setting priorities for mental health care in Nepal: a formative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):332. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJ, Kaufman A, Brenman NF, Adhikari RP, Luitel NP, Tol WA, Komproe I. Suicide in South Asia: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):358. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJ, Komproe IH, Tol WA, Nsereko J, de Jong JT. Treatment processes of counseling for children in South Sudan: a multiple n=1 design. Community Mental Health Journal. 2013;49(3):354–367. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Sharma B, van Ommeren M. Training psychosocial counselling in Nepal: Content review of a specialised training programme. Intervention. 2003;1(2):18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJD, Luitel NP, Pokharel P, Patel V. Development and pilot-testing of a mental health care plan in Nepal. British Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153718. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabura P, Fleming LM, Tobin DJ. Microcounseling Skills Training for Informal Helpers in Uganda. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2005;51(1):63–70. doi: 10.1177/0020764005053282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Rethinking psychiatry : from cultural category to personal experience. Free Press; Collier Macmillan; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA. Enhancing Common Factors in Task Sharing: Competence Evaluation & Stigma Reduction.. Paper presented at the Solving the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, Maryland. 12-13 June.2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Harper I. Navigating diagnoses: understanding mind-body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):462–491. doi: 10.1007/s11013-008-9110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ, Worthman CM, Kunz RD, Baldwin JL, Upadhaya N, Nepal MK. Political violence and mental health in Nepal: prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012a;201(4):268–275. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Maharjan SM, Timsina D, Griffith JL. Applying Nepali Ethnopsychology to Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Mental Illness and Prevention of Suicide Among Bhutanese Refugees. Annals of Anthropological Practice. 2012b;36(1):88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Bergin AE. The effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. John Wiley; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, Patel V. PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine / Public Library of Science. 2012;9(12):e1001359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine. 1990;65(9):S63–67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery EC, Kunik ME, Wilson N, Stanley MA, Weiss B. Can paraprofessionals deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy to treat anxiety and depressive symptoms? Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2010;74(1):45–62. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2010.74.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse K, McManus F. A systematic review of methods for assessing competence in cognitive– behavioural therapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(3):484–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othieno C, Jenkins R, Okeyo S, Aruwa J, Wallcraft J, Jenkins B. Perspectives and concerns of clients at primary health care facilities involved in evaluation of a national mental health training programme for primary care in Kenya. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2013;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weobong B, Nadkarni A, Weiss H, Anand A, Naik S, Kirkwood B. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lay counsellor-delivered psychological treatments for harmful and dependent drinking and moderate to severe depression in primary care in India: PREMIUM study protocol for randomized controlled trials. Trials. 2014;15(1):101. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . NVIVO qualitative data analysis software (Version 10) QSR International Pty Ltd.; Doncaster, Australia: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rakovshik SG, McManus F. Establishing evidence-based training in cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of current empirical findings and theoretical guidance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(5):496–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig S. Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1936;6(3):412. [Google Scholar]

- Singla DR, Weobong B, Nadkarni A, Chowdhary N, Shinde S, Anand A, Weiss H. Improving the scalability of psychological treatments in developing countries: an evaluation of lay therapist led therapy quality in Goa, India. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Taylor JD. Hope as a common factor across psychotherapy approaches: A lesson from the dodo's verdict. In: Snyder CR, editor. Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. Academic Press; San Diego, CA US: 2000. pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(4):293–299. doi: 10.1370/afm.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Meera S, Pian J, Patel V. Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low-and middle-income countries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;11:CD009149. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009149.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE. The research evidence for common factors models: a historically situated perspective. In: Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, editors. The Heart and Soul of Change: Delivering What Works in Therapy. Second ed. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2011. pp. 49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten K. Reasonable hope: Construct, clinical applications, and supports. Family Process. 2010;49(1):5–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance-use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) WHO Press; Geneva: 2010. p. 83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.