Abstract

The structure and biological properties of RNAs are a function of changing cellular conditions, but comprehensive, simultaneous investigation of the effect of multiple interacting environmental variables is not easily achieved. We have developed an efficient, high-throughput method to characterize RNA structure and thermodynamic stability as a function of multiplexed solution conditions using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). In a single FRET experiment using conventional quantitative PCR instrumentation, 19,400 conditions of MgCl2, ligand and temperature are analysed to generate detailed empirical conformational and stability landscapes of the cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) riboswitch. The method allows rapid comparison of RNA structure modulation by cognate and non-cognate ligands. Landscape analysis reveals that kanamycin B stabilizes a non-native, idiosyncratic conformation of the riboswitch that inhibits c-di-GMP binding. This demonstrates that allosteric control of folding, rather than direct competition with cognate effectors, is a viable approach for pharmacologically targeting riboswitches and other structured RNA molecules.

The structure and biological properties of RNAs are a function of changing cellular conditions. Here, Baird et al. report a high-throughput Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) method to rapidly compare RNA structure modulation by cognate and non-cognate ligands across multiplexed solution conditions.

The structure and biological properties of RNAs are a function of changing cellular conditions. Here, Baird et al. report a high-throughput Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) method to rapidly compare RNA structure modulation by cognate and non-cognate ligands across multiplexed solution conditions.

Many cellular RNAs adopt distinct global and local conformations in response to environmental variables such as temperature, ionic strength, the identity and concentrations of divalent cations and pH, as well as their specific or nonspecific binding to small molecules, proteins and other RNAs1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Indeed, the non-coding gene-regulatory mRNA elements known as riboswitches function by adopting different three-dimensional (3D) structures in the absence and presence of their cognate ligands9. Although non-coding RNAs, in general, and riboswitches, in particular, constitute attractive new targets for the development of drugs10,11,12,13,14, characterization of their complex responses to their environment is challenging. One-dimensional experiments that read out the response to one variable at a time may fail to uncover important facets of the molecular behaviour of an RNA, and even sparse sampling of its higher-dimensional conformational (and underlying free energy) landscape can be tedious and material intensive.

We have developed an efficient method to perform multi-dimensional biochemical and biophysical characterization of RNAs in a single high-throughput experiment. Our approach is based on Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and can be implemented on a conventional quantitative PCR (qPCR) instrument. We demonstrate that a single experiment probing 19,400 multiplexed solution conditions yields high-information content 3D and four-dimensional (4D) landscapes describing RNA conformation and tertiary structure stability as a function of Mg2+ concentration and ligand binding. We employ this approach to elucidate how the conformation and stability landscapes of a cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) riboswitch are modulated by cognate and non-cognate ligands. In addition to delineating the solution parameter range over which the RNA exhibits maximal response, our multi-dimensional analysis uncovered an alternative, inhibitory riboswitch conformation stabilized by the aminoglycoside kanamycin B, a non-cognate ligand. Additional biophysical experiments demonstrated that the non-native aminoglycoside-induced conformation modulates binding of the cognate ligand to the riboswitch. Our method for rapidly determining conformational and stability landscapes of RNA thus suggests an approach to control riboswitch function through the stabilization of off-pathway conformations using non-cognate ligands. Our method should be broadly and generally applicable for identifying small-molecule ligands exerting conformational control of functional RNAs.

Results

Complex conformational switching of a c-di-GMP-I riboswitch

The class I c-di-GMP (c-di-GMP-I) riboswitch15 regulates genes involved in motility, virulence and biofilm formation in pathogenic bacteria in response to intracellular levels of the second messenger c-di-GMP. Ligand binding-induced conformation transitions of the aptamer domain of this riboswitch have previously been described16,17. Enzymatic probing and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analyses revealed three conformations—an unfolded, extended conformation; a partially folded conformation stabilized by Mg2+; and a compact conformation stabilized by Mg2+ and c-di-GMP. The latter was elucidated by X-ray crystallography16,18. Guided by these studies, fluorophores were introduced into suitable locations to characterize the riboswitch by single-molecule FRET19 (Fig. 1a,b). The RNA was found to exist in four populations with distinct dynamic behaviours, and the relative proportions of these varied as a function of Mg2+ and c-di-GMP concentrations. Bulk measurements (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2) show that the amplitude of the FRET change that accompanies ligand binding is dampened as Mg2+ ion concentration is raised above physiologic concentrations (that is,>1 mM). Even collectively, these various experiments only sampled a handful of solution conditions. Nonetheless, their outcomes already hint at complex conformational and energetic landscapes underlying the function of this gene-regulatory RNA. Because of its important role in bacterial physiology, the c-di-GMP riboswitch is a potentially valuable target for novel antibacterial compounds. For drug discovery, it is important to develop methods more efficient than conventional SAXS and FRET to map more comprehensively the molecular behaviour of the RNA and its response to agonists and antagonists (Fig. 1c,d).

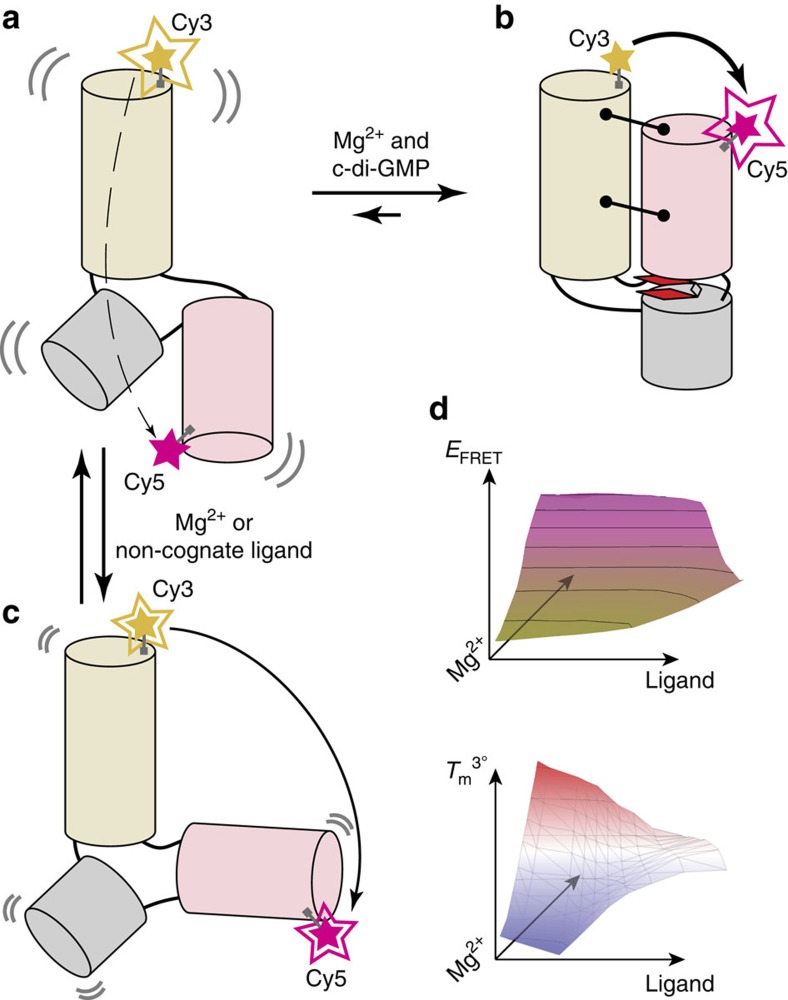

Figure 1. The c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer domain undergoes a large conformational change in response to ligand binding.

Schematics of the free (a) and ligand-bound (b) conformations of the RNA based on previous crystallographic, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), single-molecule FRET (smFRET) and enzymatic cleavage experiments16,19. Alternative conformations (c) may be stabilized under certain conditions (for example, non-cognate ligand binding). Fluorophores (Cy3, yellow and Cy5, magenta) were covalently attached to the RNA in locations that would yield large FRET changes upon folding induced by changes in c-di-GMP or Mg2+ concentrations. (a) In the absence of c-di-GMP or Mg2+, Cy3 emission is much stronger than Cy5 emission. (b) Folding to the c-di-GMP-bound conformation (tertiary contacts, black lines terminating with circles; cyclic di-GMP, red, bound between two coaxially stacked helices) results in inversion of Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence intensities, due to FRET. (c) Other conformations may yield intermediate fluorescence intensities. (d) RNA–ligand interactions can be characterized through multi-dimensional analysis of RNA conformations (FRET efficiency, EFRET) and thermal stability of the tertiary structure (Tm3°).

3D conformational landscape of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch

As previous work indicates that folding of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer domain is a function of both Mg2+ and c-di-GMP concentrations, we sought to elucidate, in a comprehensive manner, the interaction between these two variables. To achieve this rapidly, we employed a 384-well microplate fluorometer to measure the FRET efficiency (EFRET) of the labelled c-di-GMP aptamer domain under 100 different conditions (ten concentrations of Mg2+ versus ten of c-di-GMP). This experiment readily (<5 min for measurements and<5 min for data processing) produced a multi-dimensional RNA conformational landscape (Methods and Fig. 2a). As Mg2+ or c-di-GMP concentration increased, the RNA transited from unfolded to folded conformations, albeit to widely varying degrees. Three conformational states were assigned across the 100 solution conditions, consistent with previous SAXS experiments16: unfolded (EFRET ∼0.17), Mg2+-stabilized (EFRET ∼0.56) and ligand-bound (EFRET ∼0.62; ±0.012, Methods).

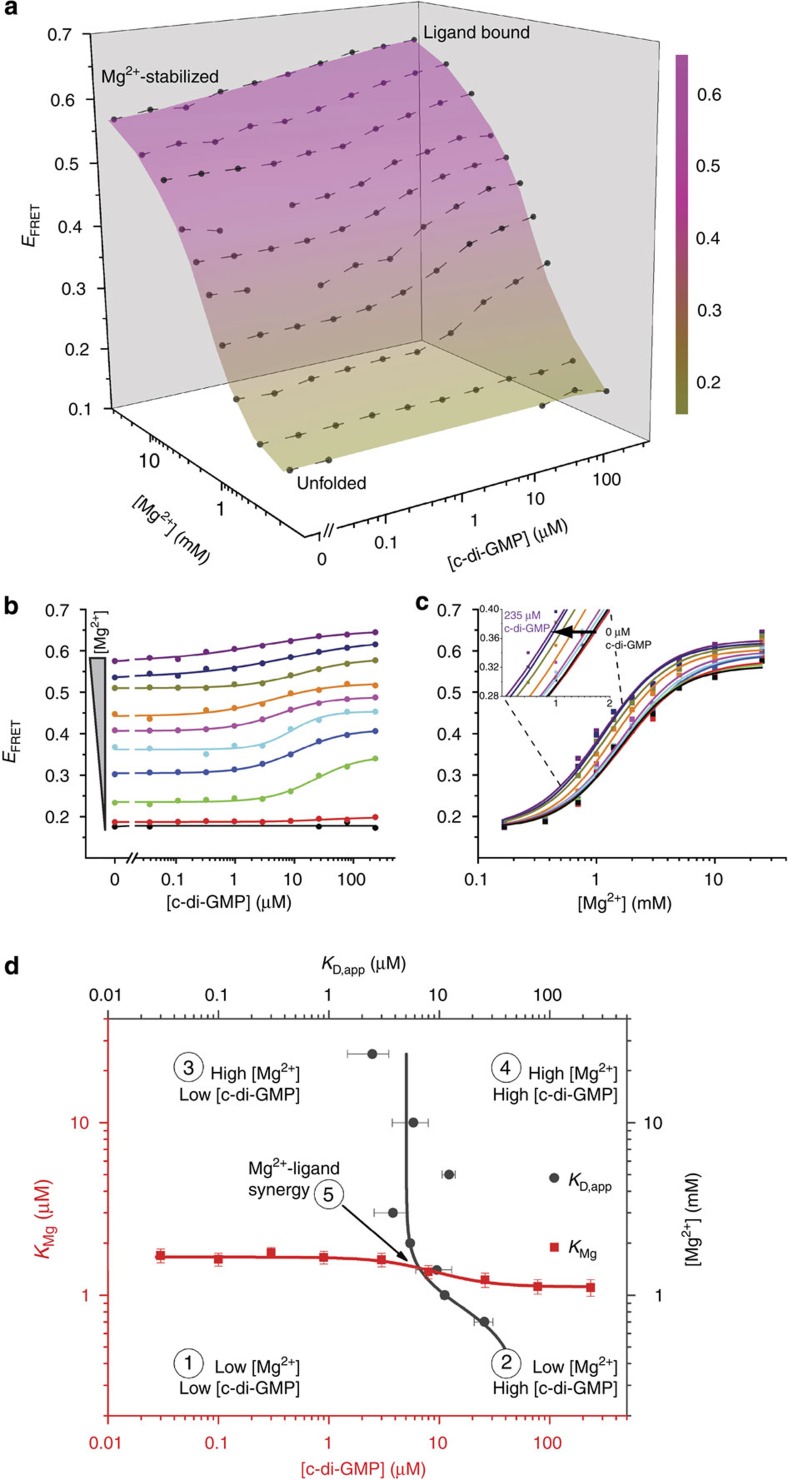

Figure 2. Experimentally determined RNA conformational landscape describes interaction of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch with its cognate ligand.

(a) Conformational landscape (coloured surface) and EFRET data (dots with connecting lines) of the riboswitch as a function of the concentrations of Mg2+ and c-di-GMP, derived from a single experiment (Methods). The average standard deviation across EFRET measurements is 0.012 and seven individual data points were removed from the data set due to spurious fluorescence measurements (Methods). The EFRET increases in response to higher Mg2+ or c-di-GMP concentrations to varying degrees under all conditions probed. Full multiplexed experimental landscapes were replicated three times. One replicate is plotted here. (b) Data re-plotted as two-dimensional titrations of c-di-GMP at various Mg2+ concentrations (from 0.167 mM, black, to 25 mM, purple). The lines represent fits to each c-di-GMP titration using a two-state binding model. (c) Data re-plotted as two-dimensional titrations of Mg2+ at various c-di-GMP concentrations (from 0 μM, black, to 235 μM, purple). The lines represent fits to each Mg2+ titration using a semi-empirical Hill-type analysis (Methods). The inset shows the gradual shift to lower Mg2+ midpoint with increasing c-di-GMP concentration. (d) A joint plot of the midpoints of each c-di-GMP titration (KD,app, grey) and each Mg2+ titration (KMg, red) describes five regimes for the response of the RNA to these two variables (see Text). The intersection of the plots (regime 5) occurs at ∼1.4 mM Mg2+ and ∼6.5 μM c-di-GMP. Here, the highest synergy is observed between Mg2+ and c-di-GMP in eliciting the RNA conformational response.

To facilitate evaluation, the 3D conformational landscape could be sectioned across either variable, yielding c-di-GMP or Mg2+ FRET titrations (Fig. 2b,c). Although extracted from a high-throughput, multi-dimensional experiment, these data are comparable in quality to those obtained from conventional 1D experiments. Comparison of FRET changes at multiple Mg2+ concentrations showed that this riboswitch exhibits maximal c-di-GMP binding-induced conformational change at near-physiologic Mg2+ concentrations20 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The landscape could also be visualized by plotting the midpoint of the transitions against either independent variable (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, a plot of c-di-GMP apparent binding affinity, KD,app, as a function of Mg2+ concentration demonstrated increasing affinity of the RNA for its cognate ligand up until 3 mM Mg2+, after which no marked enhancement in binding was observed (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The reciprocal plot of the Mg2+ concentration midpoints (KMg) as a function of c-di-GMP concentrations clearly showed that the affinity of this riboswitch construct for c-di-GMP is ∼8 μM in the region (1–1.5 mM Mg2+) of maximal conformational response (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3b).

A joint plot of KD,app and KMg for this riboswitch delineated five interaction regimes between Mg2+ and c-di-GMP (Fig. 2d). Inherently, the KD or KMg midpoints bisect each individual titration series. Connection of these midpoints across the orthogonal variable (for example, KMg at various c-di-GMP concentrations or KD,app across Mg2+ concentrations) subdivides the landscape into four regimes, with a fifth regime located at the intersection of these midpoints. First, at the lowest Mg2+ and c-di-GMP concentrations, the RNA is unfolded. Second, an increase in c-di-GMP concentrations alone produces negligible ligand binding. Third, higher Mg2+ concentrations produce a c-di-GMP binding-competent RNA state. Fourth, highly stabilizing Mg2+ concentrations dampen the conformational response to ligand binding (Fig. 2b). Fifth, at the intersection of the KD and KMg plots (∼1.4 mM Mg2+ and ∼6.5 μM c-di-GMP) lies the regime of highest synergy between Mg2+ and c-di-GMP, where the highest slopes in the Mg2+ and c-di-GMP titrations are observed (Fig. 2b, cyan and Fig. 2c, orange). Under these conditions, ligand binding-induced conformational change, the key to riboswitch function, is maximal.

A non-cognate ligand stabilizes a cryptic RNA conformer

As a step towards discovering non-cognate ligands that modulate the structure and function of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch, we examined RNA–aminoglycoside interactions. Aminoglycoside antibiotics are cationic amino-sugar molecules that inhibit protein synthesis primarily by binding to the ribosomal A-site21,22. In addition, this class of compounds has been found to interact with and modulate the function of diverse non-coding RNAs23,24,25.

Based on the ability of several aminoglycosides to promote the folding of a three-way junction in the central domain of the 16S rRNA, it was proposed that the positively charged aminoglycosides interact with RNA primarily through nonspecific charge neutralization26. When we examined the effect of the aminoglycoside kanamycin B (∼200 μM) on the c-di-GMP-I aptamer domain, we initially found that at 1 mM Mg2+ concentration, it did not bind the RNA (unchanged EFRET), whereas at 10 mM Mg2+ it appeared to unfold it (Supplementary Table 2). These results would not be expected if the interaction between the riboswitch and kanamycin B were purely a nonspecific electrostatic interaction, as higher ionic strength (high Mg2+) should weaken the interaction between the RNA and the aminoglycoside. Moreover, if the aminoglycoside were purely a nonspecific cationic counterion to the anionic RNA, it should promote its folding (higher EFRET). Control experiments using single-fluorophore-labelled constructs ruled out the possibility that kanamycin B aberrantly affects the fluorescent properties of the dyes (Supplementary Fig. 4). Given the Mg2+-dependent differences in EFRET response, we reasoned that a multiplexed analysis of this RNA–ligand interaction would better elucidate the contribution of kanamycin B to the (un)folding of this riboswitch.

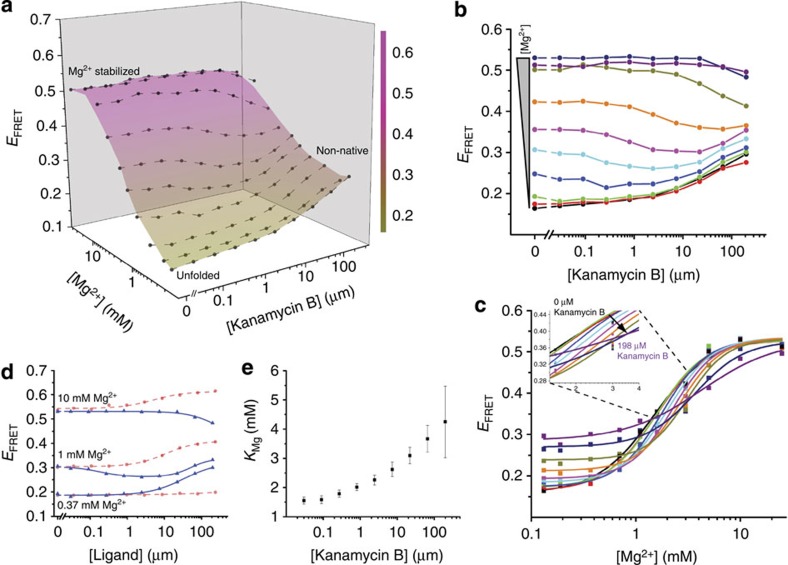

To further characterize this riboswitch–aminoglycoside interaction, we determined the corresponding 3D conformational landscape (Fig. 3a), which differed notably from the landscape of the RNA in the presence of its cognate ligand (Supplementary Fig. 5). Whereas c-di-GMP binding caused monotonic EFRET increases at nearly all measured Mg2+ concentrations (Fig. 2b), kanamycin B induced more complex patterns of change in the FRET readout (Fig. 3d). The landscape revealed a biphasic response of the riboswitch to kanamycin B (Supplementary Note 1). At low Mg2+, EFRET increased with increasing aminoglycoside concentration, whereas in high Mg2+, EFRET decreased (Fig. 3b,d; compared with Supplementary Table 2). At near-physiologic Mg2+ concentrations, increasing kanamycin B initially lowered but subsequently raised EFRET (Fig. 3b, cyan and magenta, and Fig. 3d). At 1.1 mM (Fig. 3b, cyan) and 1.4 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 3b, magenta), EFRET was essentially identical, within experimental error, at the lowest and highest aminoglycoside concentrations tested. The landscape exhibited a stable EFRET state (EFRET ∼0.30) under conditions of low Mg2+ (<1 mM) and high kanamycin B concentrations (Fig. 3a, lower right), a feature absent from the smooth c-di-GMP landscape (Fig. 2a). This additional EFRET state is also apparent when individual Mg2+ titrations are stacked side-by-side (Fig. 3c). Analysis of these titrations revealed a trend in KMg as a function of kanamycin B that did not follow the corresponding trend observed in the presence of c-di-GMP (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Taken at face value, this would mean that kanamycin B inhibits the Mg2+-induced folding transition. The complex kanamycin B-induced riboswitch conformational landscape could indicate that the aminoglycoside both unfolds and refolds the RNA in a Mg2+-dependent manner, possibly populating non-native states. A competing interpretation is that increasing kanamycin B drives the RNA monotonically down a folding pathway (leading to an idiosyncratic structure) for which the mean distance between our FRET probes (positioned to report on the native folding transition) does not vary linearly. Overall, features of the kanamycin B landscape suggest the presence of structural state(s) not populated in the c-di-GMP landscape.

Figure 3. Conformational landscape analysis of c-di-GMP-I riboswitch interaction with a non-cognate ligand reveals a cryptic non-native conformation.

(a) Conformational landscape (coloured surface) and EFRET data (dots with connecting lines) of the riboswitch as a function of the concentrations of Mg2+ and the non-cognate ligand kanamycin B. EFRET increases in response to higher Mg2+, but both increases and decreases in response to kanamycin B. Full multiplexed experimental landscapes were replicated four times. One replicate is plotted here. (b) Data re-plotted as kanamycin B titrations under various Mg2+ concentrations (from 0.132 mM, black, to 25 mM, purple). Lines connecting the data points do not represent fits and are visual aids only. (c) Data re-plotted as Mg2+ titrations under different kanamycin B concentrations (from 0 μM, black, to 198 μM, purple). Lines represent Hill-type fits to the Mg2+ titrations. The inset shows the gradual shift to higher Mg2+ midpoint with increasing kanamycin B concentration. (d) Comparison of EFRET changes at three Mg2+ concentrations (low, 0.37 mM; high, 10 mM; and near physiological, 1 mM) in response to titrations of c-di-GMP (red circles, dashed line) or kanamycin B (blue triangles, solid line). The ligands induce EFRET responses that are distinct in magnitude and sign from each other under all Mg2+ concentrations tested. (e) A plot of KMg, obtained from fits to Mg2+ titrations, as a function of kanamycin B concentration. Increasing kanamycin B concentration progressively inhibits the Mg2+-induced folding of the RNA (higher KMg).

4D thermal stability landscape analysis of RNA conformers

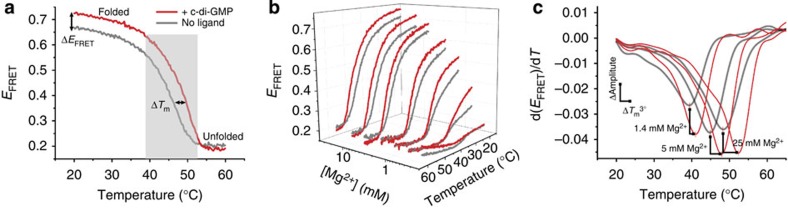

To further compare and characterize riboswitch conformations resulting from binding to different ligands, we devised a high-throughput differential scanning FRET experiment that reports on the thermodynamic stability of the structural states (Supplementary Note 2). Like the simpler differential scanning fluorimetry assay27, this experiment can be performed on a repurposed qPCR instrument. We simultaneously recorded fluorescence emission from each of 100 solution conditions spanning a broad range of Mg2+ and ligand concentrations while varying the temperature between 20 and ≥60 °C, and generated FRET melting curves (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs 6, 7 and 8). From each curve, we determined the tertiary structure unfolding midpoint (Fig. 4c), or Tm3° (Supplementary Note 3), in effect quantifying the conformational stability of the RNA under 100 conditions. This high-content 4D experiment also revealed a putative two-step tertiary folding process for the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch that had not been previously documented (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Figure 4. 4D analysis of riboswitch conformation and tertiary structural stability in a single experiment.

(a) Temperature-induced tertiary structure unfolding, measured using a qPCR machine, reported by change in EFRET in the absence (grey) and presence (red) of c-di-GMP in 10 mM Mg2+. The RNA cooperatively unfolds as temperature increases. The addition of c-di-GMP increases both EFRET and tertiary melting temperature (Tm3°). (b) 3D plot of temperature-induced tertiary unfolding showing representative data obtained from a multiplexed experimental setup (seven Mg2+ concentrations, two c-di-GMP concentrations (0, grey; 235 μM, red) and 194 temperatures; Methods). (c) Representative plots of the EFRET derivative of temperature-induced unfolding at three Mg2+ concentrations in the absence (grey) and presence (235 μM, red) of c-di-GMP. Tm3° is the minimum of each curve. The high quality of the data allows comparison of changes in Tm3° as well as the derivative amplitude, which indicates the relative fraction of folded RNA initially present in each condition.

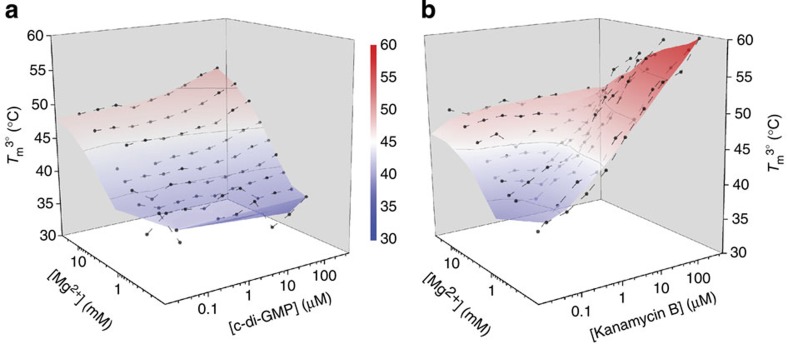

To facilitate analysis, we represented the data as 3D Tm3° landscapes over the range of Mg2+ and ligand concentrations (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 10) to allow side-by-side comparison with the conformational landscape for a given ligand and comparison of the respective Tm3° and conformational landscapes between different ligands (Supplementary Note 4). The shapes of the c-di-GMP-induced conformational and stability landscapes were similar (Figs 2a and 5a). This concordance indicated that the folding pathway of this riboswitch is free of the non-productive (that is, trapped) intermediates documented for many other RNAs28,29 (Supplementary Note 5). In this case, measurements of RNA folding and stability are interchangeable; the most folded state is also the most stable, consistent with the thermodynamic hypothesis of macromolecular folding30. In contrast, the shapes of the kanamycin B conformational and stability landscapes were dissimilar (Figs 3a and 5b).

Figure 5. Tertiary structure stability landscapes of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch in the presence of cognate and non-cognate ligand binding.

Full multiplexed experimental landscapes were replicated three times for each ligand. One replicate of each is plotted here. (a) Tm3° landscape as a function of Mg2+ and c-di-GMP. Additions of Mg2+ or c-di-GMP both monotonically increase the Tm3°. (b) Tm3° landscape as a function of Mg2+ and kanamycin B. Addition of kanamycin B does not affect the Tm3° at high Mg2+ concentrations. At low Mg2+ concentrations, the Tm3° increases in the presence of kanamycin B (see also Supplementary Fig. 10 for details). The highest Tm3° for this riboswitch was determined in the presence of the non-cognate ligand kanamycin B.

Under conditions where the additional EFRET state (∼0.30) was observed in the conformational landscape of the RNA in the presence of kanamycin B (Fig. 3a), the corresponding stability landscape exhibited the highest Tm3° (∼60 °C). Control experiments with singly labelled RNA constructs clearly demonstrate that Tm3° measurements reflect conformational stability rather than artefactual dye fluorescence in the presence of kanamycin B, over the temperature range examined (Supplementary Figs 11–13). If this EFRET state represented a productive, partially folded conformation, a commensurately intermediate Tm3° would be expected in the stability landscape. However, the Tm3° of this kanamycin B-induced state is higher than any other Tm3° measured in the presence of the cognate ligand (Fig. 5a). The disparity in shape between the kanamycin B conformational and stability landscapes indicates that an alternative conformation that was not populated in the presence of c-di-GMP was indeed stabilized (Supplementary Note 5). In this case, tertiary RNA folding and stability are not concomitant because the RNA becomes trapped in an off-pathway conformation by kanamycin B.

The kanamycin B–riboswitch interaction is specific

To test whether the association of kanamycin B with the riboswitch arose from nonspecific electrostatic interactions, we examined the impact of monovalent cations and polycationic amines on the conformation of the RNA. We generated riboswitch conformational and stability landscapes as a function of Mg2+ and monovalent cations (equimolar Na+ and K+) at up to 2 M concentration (Supplementary Fig. 14). The resulting landscapes were similar, but incongruent with the kanamycin B landscapes, suggesting that the aminoglycoside functions through a different mechanism from simple ions (Supplementary Note 5). However, it is possible that the charge density of the ligand may be more important than overall ionic strength in inducing RNA conformational change31,32. To explore this, we employed SAXS to measure the radius of gyration (Rg, a measure of macromolecular size) in the presence of various ligands including the polyamines spermine and spermidine (Fig. 6a). In low Mg2+ conditions, the compaction induced by either spermine or spermidine (300 μM final) correlated with their respective valence and charge density; spermine (4+) compacted the RNA more than spermidine (3+). This is consistent with the activity of nonspecific charge neutralization. If the primary mode of interaction between the riboswitch and kanamycin B were nonspecific charge neutralization, at minimum similar compaction should be induced by the polycationic kanamycin B (5+) as observed in the presence of spermine and spermidine. In contrast, addition of kanamycin B did not produce large changes in Rg. The RNA persisted in an expanded conformation (Rg ∼29.5 Å) that was not disrupted by the addition of up to 1 mM Mg2+, a condition under which (in the absence of the aminoglycoside) the RNA compacts readily (Fig. 6a). Together, the results of these experiments probing the role of ionic strength and charge density suggest that the kanamycin B–riboswitch interaction is not purely of nonspecific electrostatic nature, but that the aminoglycoside binds specifically to the RNA and stabilizes one or more non-native structures.

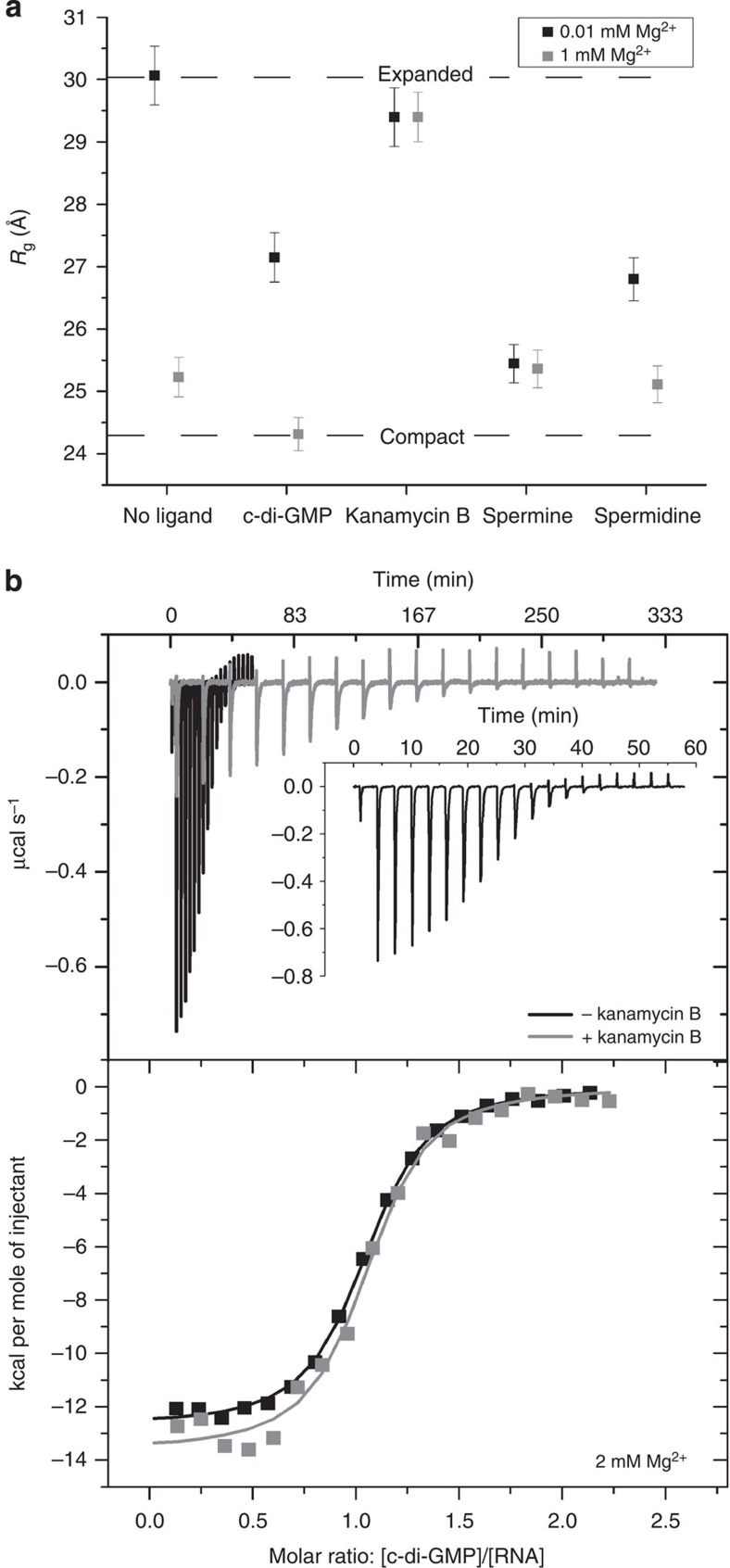

Figure 6. Kanamycin B induces an off-pathway conformation of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch.

(a) The radius of gyration (Rg) of the riboswitch (measured by SAXS) in 0.01 and 1 mM Mg2+ (black and grey, respectively) is modulated by various ligands and polyamines. Lines marking the expanded (0.01 mM Mg2+, no ligand) and compact (1 mM Mg2+,+c-di-GMP) states clearly delineate the range of Rg in these experiments. Spermine, spermidine, c-di-GMP and Mg2+ promote significant compaction of the RNA; kanamycin B does not. High-quality SAXS data were recorded for each sample one time. The error in Rg is obtained from the Guinier fit. (b) Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments wherein c-di-GMP (500 μM) was titrated into the riboswitch (50 μM) in a buffer containing 2 mM Mg2+ and either 0 μM (black) or 200 μM kanamycin B (grey). After each injection of c-di-GMP, the system equilibrates slowly when kanamycin B is present but rapidly in the absence of kanamycin B (black, and inset). The experiment is completed in less than 60 min in the absence of kanamycin B but requires nearly 333 min when kanamycin B is present. ITC experiments were performed in duplicate.

Kanamycin B modulates binding of c-di-GMP to the riboswitch

We hypothesized that the non-native structure induced by kanamycin B would modulate binding of c-di-GMP to the riboswitch. We evaluated this using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Pre-incubation of the riboswitch with kanamycin B resulted in a small decrease (∼1.4-fold) in c-di-GMP-binding affinity (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, c-di-GMP binding was more enthalpically favourable but entropically unfavourable. Similar changes were observed for ITC experiments performed in both 2 and 10 mM Mg2+. Overall, the presence of kanamycin B resulted in small but reproducible unfavourable changes in the free energy of c-di-GMP binding (Supplementary Table 3). Inspection of the raw ITC data revealed that, in contrast to the modest changes in thermodynamic parameters, the kinetics of c-di-GMP binding to the riboswitch were strongly affected by kanamycin B (Fig. 6b). In the absence of kanamycin B, each c-di-GMP injection equilibrated within 3 min (Fig. 6b, black, and inset). In contrast, up to 20 min were needed to reach equilibrium when the riboswitch was pre-incubated with the aminoglycoside (Fig. 6b, grey), demonstrating that c-di-GMP binding is slowed in the presence of kanamycin B. Thus, c-di-GMP binding may require structural rearrangement coupled to slow dissociation of kanamycin B from the riboswitch.

Discussion

We have developed a FRET-based method to examine the effect of multiple environmental variables on the conformation of an RNA in a single rapid, high-throughput experiment. Our method generates empirical high-information content RNA conformational and stability landscapes using a fluorescence microplate reader and conventional qPCR instrumentation. The biophysical approach we describe here is distinctly different from and, therefore, complementary to the majority of high-information content nucleic acid structure–function characterization methods described to date, which have implemented massively parallel sequencing technologies to explore the genotype–phenotype (that is, fitness) landscapes of functional nucleic acids33,34 and nucleic acid–protein complexes35,36,37.

By facilitating visualization of the response of RNA conformation and stability to a broad range of experimental conditions, our multi-dimensional method readily revealed properties of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch that could have been missed using conventional biophysical approaches. For instance, the lack of response of EFRET to c-di-GMP at low Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 2), or to kanamycin B at high Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 3), might have led to the erroneous conclusions that neither ligand interacts with the RNA. Instead, our experimental landscapes indicate that under those particular divalent cation concentrations, the RNA is either too unfolded or folded, respectively, to bind to the small molecules. Indeed, under conditions commonly employed to examine riboswitch–ligand interactions (for example, >20 mM Mg2+), the riboswitch–kanamycin B interaction would not have been identified using conventional ligand titration or thermal melting assays (Supplementary Note 6). Our 4D FRET method demonstrates that correct characterization of RNA ligands is highly contingent on solution conditions. Low-dimensional single-point or ligand titration assays can be insufficient to identify or characterize known and novel RNA–ligand interactions. Hence, our method, which uncovered regimes of distinct Mg2+-ligand synergy, strategically informs the design of quantitative high-throughput screening38 assays targeting RNA. Moreover, comparison of conformation and tertiary structure stability landscapes between different ligands immediately suggested the presence of otherwise hidden, alternative RNA conformations capable of ligand binding.

The stabilization of a non-native conformation of the c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer domain induced by kanamycin B binding, which we have characterized by 4D FRET, SAXS and ITC, suggests new paradigms for pharmacological targeting of small molecule-responsive RNAs. By analogy with how kanamycin B alters the binding of the cognate ligand to the riboswitch, it may be fruitful to search for new ligands that inhibit RNA function by binding non-competitively. It is now widely appreciated that many riboswitches are under kinetic, rather than thermodynamic, control39,40,41. Kinetic competition for binding with the cognate ligand, resulting from stabilization of off-pathway conformations, represents a new potential avenue for the discovery of antibiotic leads targeting bacterial riboswitches.

Our high-information content method employs instrumentation that is commonly available in many research environments (Supplementary Note 7), and can be readily extended to evaluate additional factors (for example, time, pH, interacting ligands) influencing RNA structure and function. We therefore anticipate that our multiplexed FRET approach will be useful in characterizing RNA–protein interactions42,43,44,45 or RNAs with known alternative conformations46,47, and for the development of high-throughput screening assays targeting such systems.

Methods

RNA preparation

The c-di-GMP-I riboswitch aptamer domain constructs (Supplementary Fig. 1) used in this study are derived from the tfoX 5'-UTR of Vibrio cholerae and incorporate the point mutation G20U48. The mutant RNA binds c-di-GMP with low micromolar affinity, and was chosen to facilitate the identification of weakly binding competitive ligands. The full-length aptamer domain construct (96 nt), transcribed in vitro and purified as described49, was used for SAXS and ITC. Briefly, RNA was transcribed from a PCR template and purified using denaturing PAGE. The appropriate band was excised and the RNA was then electroeluted (Elutrap, GE) overnight. The RNA was concentrated and buffer exchanged with 1 M KCl once followed by exchange with water three times using centrifugal ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra, 10k). RNA was stored at −20 °C. For fluorescence experiments, a bimolecular RNA construct identical to that previously described19, except for the G20U mutation, was employed. Briefly, two synthetic RNA oligonucleotides (Yale University Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Facility) were deprotected50 and purified by denaturing PAGE. The RNAs were electroeluted, and concentrated and washed with water by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra, Millipore). Purified RNAs were stored at −20 °C. Cy3 was incorporated during synthesis into the red strand (Supplementary Fig. 1). The blue strand contained an amine linker for labelling with Cy5. This RNA was labelled overnight as described50, ethanol precipitated and then labelled a second time to increase labelling efficiency. Following ethanol precipitation, the RNA was resuspended in 5% (v/v) acetonitrile and 95% (v/v) 50 mM triethylammonium acetate (pH 7) before loading onto a C-18 reversed-phase HPLC column (XDB-C18, Agilent) equilibrated in the same buffer. A 15-column volume gradient from 5 to 40% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 3 ml min−1 was used for purification. Typically, 15 nmoles of RNA were separated in a 9.4 × 250 mm2 column. Labelling efficiency was estimated to be 70–85% from chromatogram integration. The purified, labelled RNA was frozen (−80 °C), lyophilized, resuspended in water and stored at −20 °C.

The bimolecular RNA used for fluorescence measurements was prepared as follows. A 200 μl mixture of 5 μM Cy5-containing RNA and 7.5 μM Cy3-containing RNA were incubated overnight in folding buffer (25 mM NaCl, 25 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5) containing 2 mM MgCl2 and fractionated on a 24-ml bed-volume Superdex 75 (GE) size-exclusion chromatography column equilibrated in the same buffer. The bimolecular RNA (30 kDa) was well separated from the excess Cy3-containing RNA (10.2 kDa). Absorbance was recorded at 260, 540 and 640 nm to monitor RNA, Cy3 and Cy5, respectively. The areas under the Cy3 and Cy5 curves pertaining to the bimolecular peak were compared and the Cy5:Cy3 molar ratio was determined (1.02:1,±0.01 Cy5 molar excess).

Samples for multiplexed FRET experiments

Folding buffers (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl) containing ten different MgCl2 concentrations were prepared. A unique folding buffer was dispensed into each of ten columns in a 384-well microplate; the same Mg2+ folding buffer was present in ten rows of each column. Dual-labelled RNA was added to each of the 100 wells to a final concentration of 25 nM. For experiments containing c-di-GMP, 250 nl of a different concentrated ligand stock solution were dispensed to each of the ten rows using a mosquito Crystal (TTP Labtech). This resulted in final concentrations across the rows ranging from 0.1 to 25 mM Mg2+ and down the columns ranging from 0 to 235 μM c-di-GMP in a final volume of 21.25 μl. The microplate was covered with an aluminum seal, centrifuged for 1 min at 700 r.p.m., and incubated on an orbital shaker at 200 r.p.m. overnight at room temperature. For experiments containing kanamycin B, the RNA was incubated overnight in the absence of ligand. Then, 250 nl of each ligand stock were dispensed using a mosquito Crystal (TTP Labtech) as described above to yield a 10 × 10 matrix ranging from 0.1 to 25 mM Mg2+ and from 0 to 198 μM kanamycin B in a final volume of 25.25 μl. The microplate was covered with an aluminum seal, centrifuged for 1 min and incubated on an orbital shaker at 200 r.p.m. for 2.5 h. To evaluate the fully unfolded RNA, EDTA was added to a final concentration of 4 mM to additional RNA samples containing 0.1 mM Mg2+.

Samples for tertiary thermal melts on qPCR machine

Samples for thermal unfolding experiments were prepared similarly to the method described above for multiplexed FRET measurements. 20 μl of the samples containing c-di-GMP (described above) were transferred to a 384-well qPCR plate and centrifuged at 1,000 r.p.m. for 1 min before measurement on the qPCR machine. Samples containing kanamycin B were prepared as described above with slight modifications. The RNA was incubated in the presence of ligand overnight on an orbital shaker (200 r.p.m.) at a final concentration of 25 nM RNA in 25.25 μl. The plate was centrifuged for 1 min before measurement.

Higher noise in EFRET measurements was observed for data obtained on the qPCR machine, likely due to the sensitivity of the optical readout and background signal from the qPCR plate. The higher noise in the EFRET signal precluded fitting the Mg2+ titration and c-di-GMP titration data at room temperature. However, the determination of Tm3° was robust when compared with samples prepared at various concentrations and volumes of RNA. An increase in RNA concentration and volume (40 nM, 25 μl) did allow for robust measurements of EFRET on the qPCR machine with reduced noise and of sufficient quality to fit two Mg2+ titrations (in the absence and presence of c-di-GMP). The fits were in agreement with measurements made on the microplate fluorometer.

Fluorescence measurements and E FRET landscapes

Room temperature fluorescence measurements were recorded using a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro microplate reader with a single excitation filter corresponding to Cy3 excitation (535±12.5 nm) and two emission filters corresponding to Cy3 and Cy5 emissions (595±17.5 and 670±12.5 nm). The apparent FRET efficiency50,51 was calculated using EFRET=IA/(ID+IA). Origin 9.1 software (OriginLab) was used to generate smoothed 3D surface landscapes. The EFRET data from the 10 Mg2+ titrations were smoothed using adjacent-averaging with a window of five points (Origin 9.1). The smoothed data were plotted as a 3D surface and coloured according to the range of EFRET values. Seven data points from the c-di-GMP landscape were removed because of significantly lowered Cy3 and Cy5 reads, suggestive of insufficient volume in the well. From the kanamycin B landscape, the EFRET at 25 mM Mg2+ was unexpectedly lower than the EFRET at 10 mM Mg2+. The data in all other Mg2+ concentrations were robust and in agreement with Mg2+ titrations performed on other days. A disproportionate loss of signal of both Cy3 and Cy5 intensities at 25 mM Mg2+ was responsible for the lower EFRET and was attributed to sample adherence to the microcentrifuge tube used during sample preparation of this sample.

Tertiary thermal unfolding measurements and T m 3° landscapes

A ViiA7 (Applied Biosystems) qPCR machine was used to simultaneously record melting curves for the RNA tertiary structure under each solution condition from 20 to 70 °C using a ramp rate of 2.5 °C min−1. Cy3 and Cy5 (via FRET) emissions were measured 194 times over this range and a FRET melting curve was generated using one excitation filter 520±10 nm (Cy3) and two emission filters at 586.5±10 nm (Cy3) and 682±14 nm (Cy5). Changes in fluorescence signal outside the cooperative tertiary unfolding transition were observed because of photobleaching and the temperature-dependent quantum yields of the dyes. The EFRET thermal unfolding curves (194 data points) were smoothed using an FFT filter using a 10-point window and cutoff frequency of 0.193 (Origin 9.1). Derivatives of the smoothed EFRET thermal unfolding curves were calculated and peaks corresponding to Tm3° were identified using Origin 9.1 (OriginLab). The Tm3° landscape surface was generated by smoothing the Mg2+ titration Tm3° data using adjacent averaging (Origin 9.1).

Preparation and measurement of singly labelled RNAs

Singly labelled RNA constructs were prepared and purified identically to dual-labelled constructs. Explicitly, the Cy3-labelled oligo (red, Supplementary Fig. 1) was annealed to a RNA strand of identical sequence to the blue strand (Supplementary Fig. 1) but without a fluorophore attached. Similarly, the Cy5-labelled oligo (blue, Supplementary Fig. 1) was annealed to a RNA strand of identical sequence to the red strand (Supplementary Fig. 1) but lacking a fluorophore. Following purification by size-exclusion chromatography, as described above, samples were prepared as follows. Folding buffers (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl) containing ten different MgCl2 concentrations were prepared. Each sample contained 23 μl of buffer and 2 μl of RNA. Samples were prepared in triplicate. Following overnight incubation in the Mg2+-containing buffers, 1 μl of ligand stock or water was added. Final concentrations were 25 nM RNA in 10 Mg2+ concentrations between 0.17 and 25 mM Mg2+. Each Mg2+ titration was performed in 0 and 200 μM kanamycin B. Samples were incubated for 1.5 h followed by recording fluorescence emissions using a Tecan M1000pro. For Cy3, the excitation wavelength used was 535±20 nm and the emission wavelength was 595±20 nm. For Cy5, the excitation wavelength used was 635±20 nm and the emission wavelength was 670±20 nm. Subsequently, 21 μl of each sample were transferred to a 384-well qPCR plate and data were recorded following a total incubation time of 5 h in the presence of ligand. Thermal measurements employed a 2.5 °C min−1 ramp rate and the following filter sets: Cy3 singly labelled RNA, 520±10 nm (excitation) and 586±10 nm (emission); Cy5 singly labelled RNA, 640±10 nm (excitation) and 682±14 nm (emission).

Data analysis and fitting of titration curves

All Mg2+ titrations were fit using a semi-empirical Hill-type analysis described previously52. The signal of the unfolded state was fixed at EFRET=0.17, in accordance with that observed in the presence of 4 mM EDTA. The c-di-GMP titrations were fit to a two-state binding model to obtain KD,app. In addition, the c-di-GMP titrations were fit using a Hill analysis to obtain measures of the slope of each titration.

E FRET error analysis and data scaling

Slightly different EFRET values for Mg2+ titrations were observed for samples prepared on different days. This difference was likely due to variations in the molar ratio of the purified bimolecular construct or photobleaching of one of the dyes during sample preparation. Despite different EFRET values, similar KMg parameters were obtained from fits to the Mg2+ titrations. Furthermore, nearly identical Tm3° were measured from the thermal unfolding curves, suggesting that the unfolded and folded states were identical, despite the minor variations observed in EFRET. To establish the inherent error in EFRET measurements, data prepared on different days were compared and the Mg2+ titrations in the absence of ligand were fit using a semi-empirical Hill equation. Next, the EFRET values were normalized using the equation Sn=(S−Slow)/(Shigh−Slow), where Sn is the normalized signal, S is the observed signal, Slow is the signal of the unfolded RNA and Shigh is the signal of the folded RNA. Slow for all experiments was fixed to match the unfolded EFRET value obtained in 4 mM EDTA. Using data normalized from ten experiments performed on different days over the period of several months the average standard deviation across all EFRET values was calculated (±0.012). The error was largest (±0.02) near the Mg2+ midpoint (∼1–2 mM), where small changes in the [Mg2+] due to pipetting error result in slightly larger EFRET differences. In the low and high end of the curve, the standard deviation is ±0.01. Using the normalized parameters, the data in the kanamycin B landscape were scaled to match the EFRET range of the c-di-GMP landscape.

UV melting experiments

A bimolecular riboswitch construct, identical to that used in fluorescence experiments except lacking the fluorophores, was purified by size-exclusion chromatography as described for preparation of the labelled RNA. A 750-μl purified sample of the bimolecular riboswitch RNA was prepared in a folding buffer with final concentrations of 10 μg ml−1 RNA, 25 mM NaCl, 25 mM KCl and 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5 with either 2 or 10 mM Mg2+. Thermal melting was performed on an Agilent 8543 spectrophotometer over a temperature gradient from 20 to 90 °C in 0.1 °C increments with a 12-s equilibration at each temperature before absorbance measurements. Absorbance (260 nm) and derivative data curves were smoothed using a Savitzky-Golay 41-point filter (Origin 9.1).

Small-angle X-ray scattering experiments

A 200-μl sample of unimolecular riboswitch RNA was prepared in folding buffer with final concentrations of 615 μM RNA, 25 mM NaCl, 25 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5. The higher Mg2+ concentration was used in this folding buffer (3 mM MgCl2) in order to compensate for the high concentration of RNA52. The RNA sample was equilibrated at room temperature for >16 h. A Superdex 200 (GE) size exclusion chromatography column was pre-equilibrated with folding buffer containing 1 mM Mg2+. The RNA was purified on the column and the RNA concentration was determined before preparation of samples for SAXS experimentation. SAXS samples in 1 mM Mg2+ were prepared by mixing 35 μl of purified RNA (1.98 g l−1) with 63.5 μl of the size-exclusion chromatography buffer. To prepare SAXS samples in 0.01 mM Mg2+, 350 μl of the purified RNA were concentrated to a final concentration of 6.7 g l−1 using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (Millipore). 10 μl of this RNA stock were mixed with 88.5 μl of folding buffer containing 0 mM Mg2+. Buffer samples were prepared identically to RNA sample preparation but with the addition of appropriate folding buffer instead of RNA stock. Samples were shipped to the Advanced Photon Source with frozen cold packs. At the ID-12 BESSRC beamline, the samples were centrifuged briefly before addition of 1.5 μl of appropriate ligand (20 mM stock). The final concentration of each ligand (c-di-GMP, kanamycin B, spermine, spermidine) was 300 μM. The final RNA concentrations were 0.69 and 0.67 g l−1 for the samples in 1 and 0.01 mM Mg2+, respectively. The samples were incubated at room temperature for >11 h before data collection. Twenty consecutive exposures of 1 s were recorded while the sample was continuously flowed. Data were collected for buffer samples without RNA immediately before samples containing RNA. Data were processed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics) as described elsewhere53.

ITC experiments

The unimolecular riboswitch construct at a final concentration of 45 μM in 500 μl was mixed with folding buffer containing 2 or 10 mM MgCl2 and 0 or 200 μM kanamycin B (four total samples). An excess of the four folding buffers containing Mg2+ and kanamycin B at the aforementioned concentrations was prepared for concentration and washing of the RNA samples. The samples were concentrated tenfold using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Millipore) and washed with appropriate folding buffer. This process was repeated ≥5 times to thoroughly equilibrate the RNA in the appropriate buffers. The equilibrated samples were incubated overnight at room temperature. The following day the RNA concentrations were determined using absorbance measurements at 260 nm, including a multiplicative factor of 1.35 to correct for hypochromicity. The RNA samples were diluted in the appropriate folding buffers to achieve a final concentration of 50 μM RNA. The c-di-GMP titrant was prepared to a final concentration of 500 μM by adding 0.6 μl of 50 mM c-di-GMP to 59.4 μl of appropriate folding buffer. Hence, the buffers of the sample and the titrant were not more than 99.0% identical and a minor endothermic signal was observed as the titration curves became saturated with ligand. Raw ITC data were exported and processed using NITPIC54 and Sedphat55. The first two data points from each experiment were removed because of large residuals to the initial fit. ITC experiments were performed in duplicate.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Baird, N. J. et al. Rapid RNA–ligand interaction analysis through high-information content conformational and stability landscapes. Nat. Commun. 6:8898 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9898 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-13, Supplementary Tables 1-3, Supplementary Notes 1-7 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Hogg for use of the microplate fluorometer; T. Christopher and R. Bonasio for use of qPCR instrumentation for single-fluorophore control experiments; P. Berget for use of the microplate fluorometer for single-fluorophore control experiments, G. Piszczek for support with ITC and initial fluorescence experiments; R. Macarthur for discussions aiding data analysis; Y.-X. Wang and X. Zuo for experimental SAXS beam time and support, respectively; and J. Zhang, M. Lau, C. Jones and S. Bachas for insightful comments. This work was supported by the intramural programmes of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, NIH and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH and a 2013 Director's Challenge Innovation Award, NIH. N.J.B. is a recipient of a K22 NHLBI Career Transition Award (K22-HL121113A).

Footnotes

Author contributions N.J.B. and A.R.F.-D'A conceived the project; N.J.B. designed and executed experiments and analysed data; N.J.B. and A.R.F.-D'A wrote the paper with contributions from J.I. A.R.F.-D'A and J.I. advised N.J.B. throughout the project.

References

- Bhaskaran H. & Russell R. Kinetic redistribution of native and misfolded RNAs by a DEAD-box chaperone. Nature 449, 1014–1018 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. et al. Protein-guided RNA dynamics during early ribosome assembly. Nature 506, 334–338 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A. & Nudler E. A decade of riboswitches. Cell 152, 17–24 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper D. E. A guide to ions and RNA structure. RNA. 10, 335–343 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy S. et al. Riboswitches. A riboswitch-containing sRNA controls gene expression by sequestration of a response regulator. Science 345, 937–940 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellin J. R. et al. Riboswitches. Sequestration of a two-component response regulator by a riboswitch-regulated noncoding RNA. Science 345, 940–943 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. J. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Modulation of quaternary structure and enhancement of ligand binding by the K-turn of tandem glycine riboswitches. RNA 19, 167–176 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reining A. et al. Three-state mechanism couples ligand and temperature sensing in riboswitches. Nature 499, 355–359 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. J. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Idiosyncratically tuned switching behavior of riboswitch aptamer domains revealed by comparative small-angle X-ray scattering analysis. RNA 16, 598–609 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhbacher J. et al. Novel riboswitch ligand analogs as selective inhibitors of guanine-related metabolic pathways. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000865 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deigan K. E. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Riboswitches: discovery of drugs that target bacterial gene-regulatory RNAs. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 1329–1338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. R. & Hergenrother P. J. Targeting RNA with small molecules. Chem. Rev. 108, 1171–1224 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount K. F. & Breaker R. R. Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nature Biotechnol. 24, 1558–1564 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunse C. E., Schuller A. & Mayer G. The promise of riboswitches as potential antibacterial drug targets. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304, 79–92 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan N. et al. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science 321, 411–413 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulshina N., Baird N. J. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Recognition of the bacterial second messenger cyclic diguanylate by its cognate riboswitch. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1212–1217 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. J., Kulshina N. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Riboswitch function: flipping the switch or tuning the dimmer? RNA Biol. 7, 328–332 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. D. et al. Structural basis of ligand binding by a c-di-GMP riboswitch. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1218–1223 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S., Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. & Rueda D. Allosteric tertiary interactions preorganize the c-di-GMP riboswitch and accelerate ligand binding. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 920–927 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatossava T., Jutte H., Kuhn A. & Kellenberger E. Manipulation of intracellular magnesium content in polymyxin B nonapeptide-sensitized Escherichia coli by ionophore A23187. J. Bacteriol. 162, 413–419 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D. & Noller H. F. Interaction of antibiotics with functional sites in 16S ribosomal RNA. Nature 327, 389–394 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock J., Moazed D., Cannon M., Davies J. & Noller H. F. Interaction of antibiotics with A- and P-site-specific bases in 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J 10, 3099–3103 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw D. J. & Gait M. J. Hairpin ribozyme cleavage catalyzed by aminoglycoside antibiotics and the polyamine spermine in the absence of metal ions. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 5551–5561 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tor Y., Hermann T. & Westhof E. Deciphering RNA recognition: aminoglycoside binding to the hammerhead ribozyme. Chem. Biol. 5, R277–R283 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ahsen U., Davies J. & Schroeder R. Antibiotic inhibition of group I ribozyme function. Nature 353, 368–370 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermeier D., Sears P., Wong C. H., Millar D. P. & Williamson J. R. A three-fluorophore FRET assay for high-throughput screening of small-molecule inhibitors of ribosome assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 2707–2715 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen F. H., Berglund H. & Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. RNA misfolding and the action of chaperones. Front. Biosci. 13, 1–20 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnick T. R. & Pan T. RNA folding: models and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 309–316 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein C. J., Goldberger R. F. & Anfinsen C. B. The genetic control of tertiary protein structures: studies with model systems. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 28, 439–449 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- Koculi E., Lee N. K., Thirumalai D. & Woodson S. A. Folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme by polyamines: importance of counterion valence and size. J. Mol. Biol. 341, 27–36 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koculi E., Thirumalai D. & Woodson S. A. Counterion charge density determines the position and plasticity of RNA folding transition states. J. Mol. Biol. 359, 446–454 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt J. N. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Rapid construction of empirical RNA fitness landscapes. Science 330, 376–379 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther U. P. et al. Hidden specificity in an apparently nonspecific RNA-binding protein. Nature 502, 385–388 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tome J. M. et al. Comprehensive analysis of RNA-protein interactions by high-throughput sequencing-RNA affinity profiling. Nat. Methods 11, 683–688 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro J. D. et al. Quantitative analysis of RNA-protein interactions on a massively parallel array reveals biophysical and evolutionary landscapes. Nature Biotechnol. 32, 562–568 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutiu R. et al. Direct measurement of DNA affinity landscapes on a high-throughput sequencing instrument. Nature Biotechnol. 29, 659–664 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese J. et al. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11473–11478 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lau M. W. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Ribozymes and riboswitches: modulation of RNA function by small molecules. Biochemistry 49, 9123–9131 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickiser J. K., Cheah M. T., Breaker R. R. & Crothers D. M. The kinetics of ligand binding by an adenine-sensing riboswitch. Biochemistry 44, 13404–13414 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickiser J. K., Winkler W. C., Breaker R. R. & Crothers D. M. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol. Cell 18, 49–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowsky E. & Bowers H. Remodeling of ribonucleoprotein complexes with DExH/D RNA helicases. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 4181–4188 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. G. & Hall K. B. Linkage and allostery in snRNP protein/RNA complexes. Biochemistry 53, 3529–3539 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. G. & Hall K. B. Binding affinity and cooperativity control U2B''/snRNA/U2A' RNP formation. Biochemistry 53, 3727–3737 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity T. S., Fried H. M. & Weeks K. M. Anti-cooperative assembly of the SRP19 and SRP68/72 components of the signal recognition particle. Biochem. J. 415, 429–437 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. et al. Conformational inhibition of the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site RNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 823–825 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon J. C., Prestwood L. J., Le Grice S. F. & Lever A. M. In-gel probing of individual RNA conformers within a mixed population reveals a dimerization structural switch in the HIV-1 leader. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e174 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. D., Lipchock S. V., Livingston A. L., Shanahan C. A. & Strobel S. A. Structural and biochemical determinants of ligand binding by the c-di-GMP riboswitch. Biochemistry 49, 7351–7359 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Edwards T. E. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Structural basis for specific, high-affinity tetracycline binding by an in vitro evolved aptamer and artificial riboswitch. Chem. Biol. 15, 1125–1137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D. & Walter N. G. Fluorescent energy transfer readout of an aptazyme-based biosensor. Methods Mol. Biol. 335, 289–310 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R., Hohng S. & Ha T. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat. Methods 5, 507–516 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. J., Westhof E., Qin H., Pan T. & Sosnick T. R. Structure of a folding intermediate reveals the interplay between core and peripheral elements in RNA folding. J. Mol. Biol. 352, 712–722 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. J. & Ferré-D'Amaré A. R. Analysis of riboswitch structure and ligand binding using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Methods Mol. Biol. 1103, 211–225 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S. et al. High-precision isothermal titration calorimetry with automated peak-shape analysis. Anal. Chem. 84, 5066–5073 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman J. C. et al. Studying multisite binary and ternary protein interactions by global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data in SEDPHAT: application to adaptor protein complexes in cell signaling. Protein Sci. 16, 30–42 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-13, Supplementary Tables 1-3, Supplementary Notes 1-7 and Supplementary References