Abstract

Background:

Telepathology is increasingly being employed to support diagnostic consultation services. Prior publications have addressed technology aspects for telepathology, whereas this paper will address the clinical telepathology experience of KingMed Diagnostics, the largest independent pathology medical laboratory in China. Beginning in 2012 the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and KingMed Diagnostics partnered to establish an international telepathology consultation service.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective study that summarizes the telepathology experience and diagnostic consultation results between UPMC and KingMed over a period of 3 years from January 2012 to December 2014.

Results:

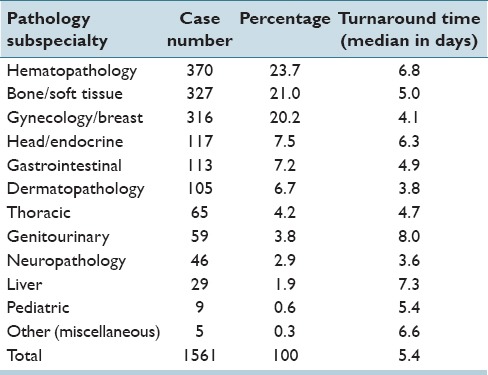

A total of 1561 cases were submitted for telepathology consultation including 144 cases in 2012, 614 cases in 2013, and 803 in 2014. Most of the cases (61.4%) submitted were referred by pathologists, 36.9% by clinicians, and 1.7% by patients in China. Hematopathology received the most cases (23.7%), followed by bone/soft tissue (21.0%) and gynecologic/breast (20.2%) subspecialties. Average turnaround time (TAT) per case was 5.4 days, which decreased from 6.8 days in 2012 to 5.0 days in 2014. Immunostains were required for most of the cases. For some difficult cases, more than one round of immunostains was needed, which extended the TAT. Among 855 cases (54.7%) where a primary diagnosis or impression was provided by the referring local hospitals in China, the final diagnoses rendered by UPMC pathologists were identical in 25.6% of cases and significantly modified (treatment plan altered) in 50.8% of cases.

Conclusion:

These results indicate that international telepathology consultation can significantly improve patient care by facilitating access to pathology expertise. The success of this international digital consultation service was dependent on strong commitment and support from leadership, information technology expertise, and dedicated pathologists who understood the language and culture on both sides. Lack of clinical information, missing gross pathology descriptions, and insufficient tissue sections submitted for evaluation were the main reasons for indefinite diagnoses. The overall experience encourages international telepathology practice for second opinions.

Keywords: China, digital pathology, teleconsultation, telepathology, whole slide imaging

INTRODUCTION

Telepathology refers to the remote practice of pathology via transmitting digital images. Since the introduction of telepathology almost 46 years ago, there have been several changes in technology.[1,2] As a result, telepathology has transitioned from static to whole slide imaging (WSI). WSI (virtual microscopy) refers to the digitization of glass slides by scanners to generate high-resolution digital slides. Operationally, it is often easier to move an image than it is to move a pathologist or patient (or the glass slides of a patient's specimen). For the purpose of telepathology, digital files can either be accessed on a remotely shared server or transmitted and/or uploaded to a server hosted by a consulting group or vendor offering storage (cloud) services.

Telepathology has been reported to improve patient care by offering technology that facilitates access to pathology experts.[3] Over the years, WSI has been increasingly employed to support diagnostic consultation services.[4,5,6,7,8] An early example of international teleconsultation is iPATH, a telepathology platform developed by the University of Basel in 2001.[9] International telepathology networks have since been created by several academic institutions including the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC).[5,10,11] In addition, several commercial solutions have become available that offer clients the tools to partake in telepathology and purchase cloud services (e.g. Corista, Xifin, Proscia).

Most telepathology publications to date have dealt more with the technology aspects than the clinical experience of this practice. The aim of this study was to share 3 years’ worth of experience involving international teleconsultation between UPMC and KingMed Diagnostics in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Telepathology Partners

Since 2012, UPMC and KingMed Diagnostics in China established a UPMC-KingMed International Telepathology Consultation Center in Guangzhou KingMed.

The UPMC is a tertiary academic medical center located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the USA. UPMC Department of Pathology includes multiple academic centers and community hospitals. The Anatomical Pathology Department within the academic medical centers (UPMC Presbyterian, UPMC Shadyside, UPMC Magee, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh) is structured using a center of excellence model, where anatomical pathology cases are handled and signed out only by subspecialty pathologists (e.g. Neuropathology, Dermatopathology, Cytopathology, etc.). Cases received from KingMed Diagnostics for consultation get assigned to appropriate subspecialty pathologists.

KingMed Diagnostics is a large network with 27 central pathology laboratories serving 13,600 Hospitals and Clinics in China. Guangzhou KingMed Diagnostics (Guangzhou, China) is the first pathology laboratory to be fully certified in both anatomic and clinical pathology by the College of American Pathologists in China.[12,13,14,15] Guangzhou KingMed Diagnostics was also certified by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 15189). The diagnosis rendered by expert pathologists from UPMC is regarded as a second opinion and not used for primary diagnosis. Since UPMC pathologists were not licensed to practice medicine in China, KingMed were legally responsible for final diagnoses on consultation cases. The pathologists from Guangzhou KingMed telepathology consultation center sign out a final report in Chinese for each case. Patients receive both an English report from the UPMC pathologist and Chinese report from KingMed pathologists. The pathologists at the Guangzhou KingMed telepathology consultation center only gave a final diagnosis after slides had been reviewed by UPMC pathologists.

Whole Slide Imaging

The technology employed to support telepathology between UPMC and KingMed in China has been previously described.[5,11,16] In brief, a customized web-based digital pathology consultation portal was developed [Figure 1]. Glass slides were scanned in China using a NanoZoomer scanner (NanoZoomer 2.0-HT, Hamamatsu). All slides were scanned at 20×, except for hematopathology cases that were scanned at 40×. The hematopathologists at UPMC requested higher resolution images upfront to facilitate their interpretation of cases. For the first 2 years, WSI submitted for consultation resided on the client's server (Hammamatsu NDP.serve) in China. Pathology consultants from Pittsburgh in the USA used the UPMC web portal to securely access these images on the client's server. Workflow (e.g., case triage, transcription) and reporting were incorporated into this web-based application. In the 3rd year, digital slides were transferred without compression to a server in Pittsburgh, USA using commercial file transfer software (Aspera). This improved viewing of WSI by avoiding latency issues.[16]

Figure 1.

Customized University of Pittsburgh Medical Center KingMed teleconsultation web portal

Telepathology Operation

In China, each KingMed branch located within different cities nationwide received telepathology consultation cases from local pathologists, clinicians, and/or at the request of patients to be sent to the KingMed Consultation Center in Guangzhou. The KingMed consultation center handled all incoming slides and blocks for consultation. Tissue sections for routine H & E staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were cut at 3 µm. Hematopathology slides were sectioned at 2 µm. Although attempts were made to enhance slide and stain quality as much as possible for telepathology purposes, there were still differences in slide quality depending on which KingMed site generated the slides. For difficult surgical pathology cases requiring consultation, initial glass slides (H & E and when included immunohistochemical stained slides) were screened at Guangzhou KingMed center before being referred to UPMC expert pathologists. Glass slides and tissue blocks were not permitted to be physically mailed to UPMC in the USA due to Chinese regulations. In other words, consultations were handled entirely digitally without the option to defer to glass slides. This also limited glass slides being sent later to Pittsburgh for quality assurance, re-review of a proportion of cases after diagnoses were rendered. UPMC and KingMed pathologists had the ability to communicate bidirectionally [Figure 2], which allowed pathologists to request additional information (e.g., clinical findings, gross pathology details, flow cytometry data, etc.) and if necessary even radiology images. If required, UPMC pathologists were allowed to order additional stains including immunostains to further work up cases. These additional slides were prepared at the Guangzhou KingMed Center, then digitized and added to the existing consult case. At the outset, both partners established an agreeable stain quality and menu of immunohistochemical stains available in China. At the start of this collaboration, UPMC pathologists reviewed 10 cases with glass slides compared to scanned images to confirm quality. Participating pathologists at UPMC were trained to use the telepathology portal. Dedicated information technology (IT) staff at both partnering institutions maintained the telepathology infrastructure, monitored turnaround time (TAT), and were involved in troubleshooting technical issues.

Figure 2.

Screenshot from the telepathology portal illustrating the value of bidirectional communication

A retrospective study using descriptive statistics was performed evaluating the consultation experience and diagnostic results between UPMC and KingMed over a 36 month period (January 2012 - December 2014). TAT and diagnostic discordance were recorded. TAT was counted as the time when UPMC received scanned images to the time when UPMC pathologists signed out the case with a final diagnostic interpretation. When performed, TAT included the time needed for additional procedures such as performing IHC stains or molecular analysis. Based on the final diagnosis rendered by UPMC expert pathologists, the cases were divided into three groups: those with definitive (certain) diagnoses, suggestive (favored) diagnoses, and atypical (indeterminate) diagnoses.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at KingMed Diagnostics.

RESULTS

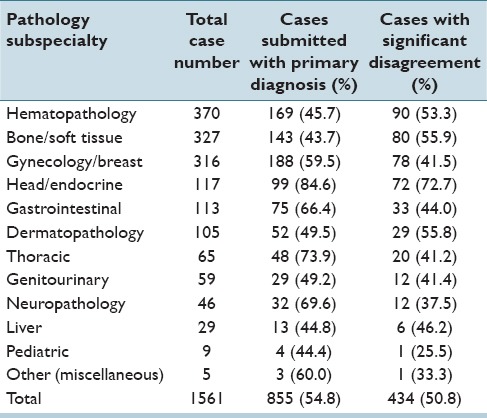

During the 3 year study period, there were 1561 cases sent for consultation to UPMC including 144 cases in 2012, 614 in 2013, and 803 in 2014. The volume of cases submitted for consultation increased annually. The distribution of cases among different body systems and the corresponding TAT for rendering a final consultation diagnosis is listed in Table 1. Hematopathology received the most cases (23.7%), followed by bone/soft tissue pathology (21.0%) and gynecologic/breast (20.2%) subspecialties. The average TAT was 6.8 days in 2012, 5.3 days in 2013, and 5.0 days in 2014. Subsequent immunostains were ordered for most of the cases. For certain cases, especially in hematopathology, more than one round of immunostains was needed which increased the TAT. Overall, the average TAT gradually improved as did user satisfaction with the system based on subjective evaluation.

Table 1.

Teleconsultation case distribution and turnaround time

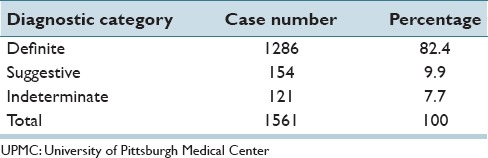

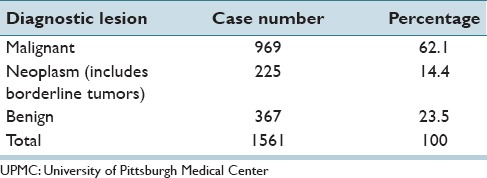

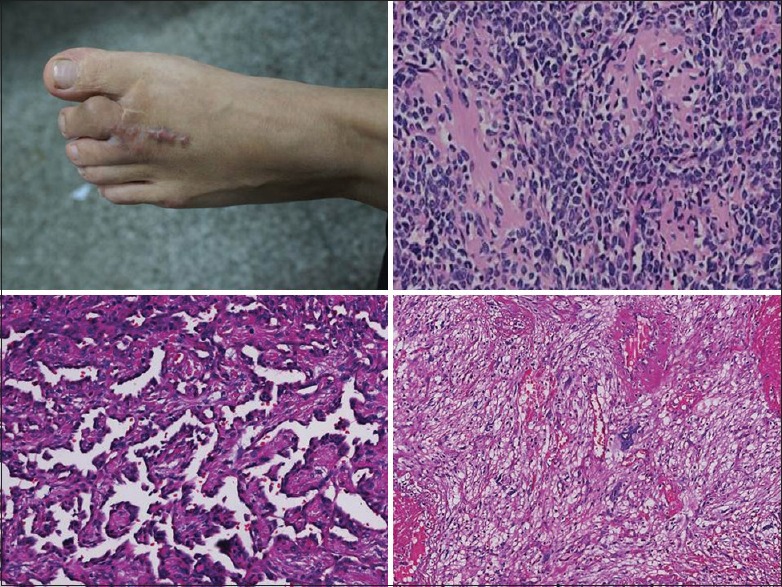

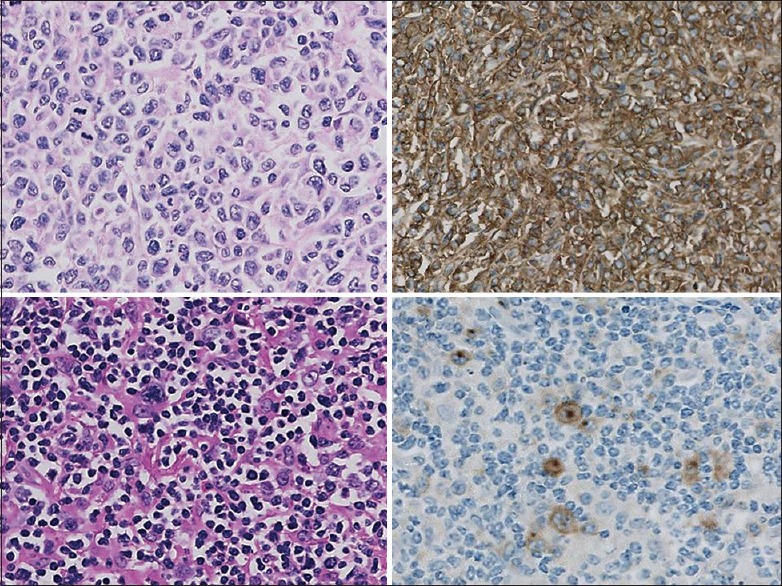

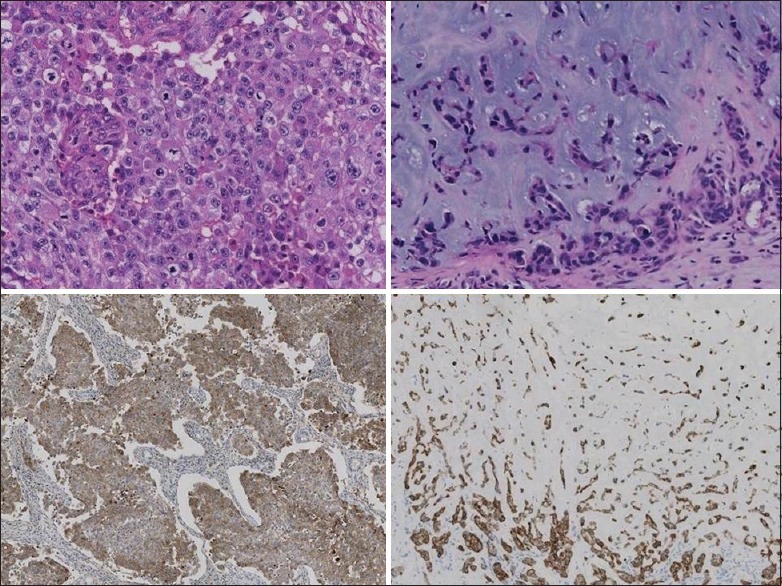

In most (82.4%) cases, a definite diagnosis was provided [Table 2]. The main reasons for not providing a definite diagnosis included lack of clinical information, missing gross description, insufficient tissue sections submitted, and/or no material available to perform additional immunostains. Table 3 demonstrates the nature of the lesions diagnosed by UPMC expert pathologists. Malignancies accounted for most of the cases (62.1%). Cases sent for consultation in general were either difficult to diagnose or were rare entities [Figures 3–5]. Since KingMed is an independent reference laboratory, information on follow-up surgical resection specimens was not made available to UPMC. This feedback would be beneficial, especially in discrepant cases.

Table 2.

Final diagnoses rendered by UPMC expert pathologists

Table 3.

Diagnostic entities rendered by UPMC expert pathologists

Figure 3.

Examples of challenging soft tissue pathology consultation cases. (Top left) recurrent acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma. The clinical image shown in this case was supplied by KingMed upon request. (Top right) Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. (Bottom left) retiform hemangioendothelioma. (Bottom right) Pleomorphic hyalinizing angiectatic tumorwere

Figure 5.

Examples of challenging lymphoma consultation cases. (Top panel) anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (top left H & E; top right CD30 immunostain). (Bottom panel) classical Hodgkin lymphoma (bottom left H & E; bottom right CD30 immunostain)

Figure 4.

Examples of rare gynecologic and breast pathology consultation cases. (Left panel) 17-year-old female with an ovarian embryonal carcinoma (top left H & E; bottom left positive CD30 immunostain). (Right panel) 45-year-old female with a breast metaplastic carcinoma showing chondroid differentiation (top right H & E; bottom right cytokeratin 5/6 immunostain)

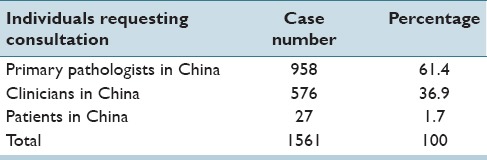

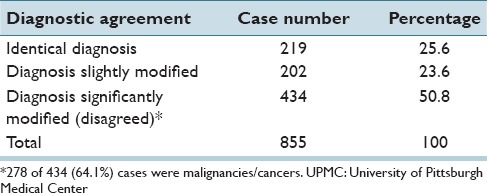

The original diagnoses for cases submitted for consultation were recorded and analyzed. Most cases were referred by pathologists, followed by requests from primary clinicians in China for cases to be sent to the USA for a second opinion [Table 4]. Of 1561 consulted cases, 706 cases (45.2%) were sent for consultation without an initial primary diagnosis or diagnostic impression. For the remaining 855 cases (54.7%) where a primary diagnosis or initial impression was made by the primary pathologists in China, the level of diagnostic agreement between UPMC expert pathologists and primary pathologists was assessed. For cases were a primary diagnosis was submitted, UPMC expert pathologists agreed with that primary diagnosis or impression in 25.6% of cases, and completely disagreed or considerably modified the primary diagnosis (i.e., the treatment plan was altered, and/or prognosis differed) in 50.8% of cases [Table 5], which included 278 cases of malignancies/cancers. The organ distribution for cases with primary diagnoses that had disagreements are listed in Table 6. Of note, hematopathology, and bone/soft tissue cases received a lower percentage of cases with a primary diagnosis (45.7% and 43.7%), indicating the difficulty general pathologists have with pathological evaluation of these organs. The disagreement rates for hematopathology and bone/soft tissue cases were 53.3% and 55.9%, respectively. For the 59.5% of gynecology/breast cases that had primary diagnoses, the disagreement rate was 41.5%, which is lower than that seen with hematopathology and bone/soft tissue cases. Surprisingly, 84.6% of head/endocrine cases submitted with a primary diagnosis showed that 72.7% of these cases had disagreement [Table 6].

Table 4.

Referral nature of cases submitted for telepathology consultation

Table 5.

Agreement of diagnoses between UPMC expert pathologists and the primary pathologists in China

Table 6.

Teleconsultation case distribution with significantly modified diagnoses

DISCUSSION

There have been limited studies about the use of telepathology in China.[17,18,19] Chen et al. report of a government supported telepathology consultation and quality control program for cancer diagnosis in China indicated that telepathology could play an important role in improving pathology diagnoses in China.[19] To date, there have been no large studies showing the success of telepathology involving China and other countries. The results of this study indicate, for the first time, that international telepathology consultation can improve patient care in China by facilitating access to pathology expertise. The ongoing success and marketing effort of the telepathology collaboration between UPMC and KingMed resulted in an increased number of cases being submitted for consultation each year. Teleconsultation, in turn, improved the quality of care for patients since the second opinions modified the primary diagnosis (i.e., the treatment plan was likely to be altered, and/or prognosis differed) in 50.8% of cases. Of note, 64.1% of these cases were malignancies/cancers. The shift in requests for consultation from pathologists at first to treating clinicians and then even to patients themselves later indicates the value placed on obtaining an expert pathology opinion. Similar results were reported in a national telepathology consultation and quality control program in China.[19] That study showed that 24.2% of cases had expert's opinion significantly different from submitting pathologists. For the purposes of this study, significant difference means a change from malignant to benign or from benign to malignant. The rate increases to 28.8% if cases without a preliminary diagnosis were excluded.[19] Based on our experience, the highest disagreement rates were seen with head and neck/endocrine cases, hematopathology, bone/soft tissue and then gynecology/breast cases, which may indicate the difficulty general pathologists have with making pathology diagnoses in these cases. Our study was not intended to compare diagnostic capabilities between pathologists in China and the USA, but rather to demonstrate that telepathology is a convenient mechanism to assist those seeking consultation. Moreover, there are three general levels of hospitals in China: Level 3 are the large hospitals located in big cities, level 2 are mid-sized hospitals located in small-middle cities, and level 1 which are hospitals present in the countryside, suburbs or small cities. Most cases referred for telepathology consultation were from level 1 to 2 hospitals. Hence, the primary diagnostic accuracy for this study does not fully represent the diagnostic skill of all Chinese pathologists. In addition, immunohistochemical studies requested to subsequently work-up cases submitted for teleconsultation can be helpful in the final diagnosis. The Pathology Consultation service through the centers of excellence can offer comprehensive consultations in anatomic pathology, cytology, electron microscopy, IHC, flow cytometry, image analysis, cytogenetics, and molecular diagnostics to all levels of hospitals in the United States and other countries. Indirect benefits of this telepathology partnership include education, skill enhancement for pathologists from both parties, and academic collaboration.[13,14,15]

A prior systematic review of general international telemedicine collaborations revealed several factors that were essential to success.[20] They included low operating costs, use of simple technologies, bi-directional communication, incentive-based programs, locally responsive services, strong team leadership, appropriate training, and user acceptance. The success of our international digital consultation service was dependent on strong commitment and support from leadership, IT expertise, and dedicated pathologists who understood the language and culture on both sides. In addition, we customized our web portal to satisfy the needs of both the referring site and consulting pathologists. This included a simple user interface and a built-in mechanism to support bi-directional discussions. Pathologists also received extensive training and consultants were offered a financial incentive to participate.

For any cross-border telemedicine venture, there are likely to be barriers. Some of these obstacles include legal/regulatory issues, sustainability factors (e.g., high cost, inconsistent use, poor scalability), cultural factors (e.g., different language, trust issues), and contextual factors (e.g. IT infrastructure, network limitations, time zones).[20] Indeed, some of the challenges we encountered included Internet speed restrictions and overcoming firewalls, differences in culture and health care systems, lack of clinical information and gross pathology descriptions with some cases, insufficient tissue sections submitted for evaluation, and difficulties related to direct communication with Chinese clinicians.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a retrospective review of teleconsultation experience between UPMC in the USA and KingMed Diagnostics in China shows a successful, sustainable and growing international partnership. Leveraging technology to facilitate access to remote pathology experts has resulted in great improvement of patient care in China. Therefore, international telepathology practice for second opinions should be encouraged.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

An abstract was partially presented at the USCAP 104th Annual Meeting in Boston, MA. March 21–27, 2015. The authors would like to thank all the UPMC consultants for their dedicated work.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.jpathinformatics.org/text.asp?2015/6/1/63/170650

Contributor Information

Chengquan Zhao, Email: zhaoc@upmc.edu.

Liron Pantanowitz, Email: pantanowitzl@upmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinstein RS, Descour MR, Liang C, Bhattacharyya AK, Graham AR, Davis JR, et al. Telepathology overview: From concept to implementation. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1283–99. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.29643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S, Parwani AV, Aller RD, Banach L, Becich MJ, Borkenfeld S, et al. The history of pathology informatics: A global perspective. J Pathol Inform. 2013;4:7. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.112689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May M. A better lens on disease. Sci Am. 2010;302:74–7. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0510-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilbur DC, Madi K, Colvin RB, Duncan LM, Faquin WC, Ferry JA, et al. Whole-slide imaging digital pathology as a platform for teleconsultation: A pilot study using paired subspecialist correlations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1949–53. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.12.1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantanowitz L, Wiley CA, Demetris A, Lesniak A, Ahmed I, Cable W, et al. Experience with multimodality telepathology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. J Pathol Inform. 2012;3:45. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.104907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer TW, Slaw RJ. Validating whole-slide imaging for consultation diagnoses in surgical pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1459–65. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0541-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vodovnik A. Distance reporting in digital pathology: A study on 950 cases. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:18. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.156168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones NC, Nazarian RM, Duncan LM, Kamionek M, Lauwers GY, Tambouret RH, et al. Interinstitutional whole slide imaging teleconsultation service development: Assessment using internal training and clinical consultation cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:627–35. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0133-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brauchli K, Oberholzer M. The iPath telemedicine platform. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11:S3–7. doi: 10.1258/135763305775124795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minervini MI, Yagi Y, Marino IR, Lawson A, Nalesnik M, Randhawa P, et al. Development and experience with an integrated system for transplantation telepathology. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1334–43. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.29655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero Lauro G, Cable W, Lesniak A, Tseytlin E, McHugh J, Parwani A, et al. Digital pathology consultations - A new era in digital imaging, challenges, and practical applications. J Digit Imaging. 2013;26:668–77. doi: 10.1007/s10278-013-9572-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khetarpal S, Kamis S. Tracing the rise of King med and its future route: A correspondence with Hongbo Li. Asian Pac Biotech News. 2012;16:20–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng B, Austin RM, Liang X, Li Z, Chen C, Yan S, et al. Bethesda System reporting rates for conventional Papanicolaou tests and liquid-based cytology in a large Chinese, College of American Pathologists-certified independent medical laboratory: Analysis of 1394389 Papanicolaou test reports. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:373–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0070-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng B, Li Z, Griffith CC, Yan S, Chen C, Ding X, et al. Prior high-risk HPV testing and Pap test results for 427 invasive cervical cancers in China's largest CAP-certified laboratory. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:428–34. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng B, Austin RM, Liang X, Li Z, Chen C, Yang S, et al. PPV of HSIL cervical cytology result in China's largest CAP-certified laboratory. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantanowitz L, McHugh J, Cable W, Zhao C, Parwani AV. Imaging file management to support international telepathology. J Pathol Inform. 2015;6:17. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.153917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Liu J, Xu H, Gong E, McNutt MA, Li F, et al. A feasibility study of virtual slides in surgical pathology in China. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1842–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Gong E, McNutt MA, Liu J, Li F, Li T, et al. Assessment of diagnostic accuracy and feasibility of dynamic telepathology in China. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Jiao Y, Lu C, Zhou J, Zhang Z, Zhou C. A nationwide telepathology consultation and quality control program in China: Implementation and result analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:S2. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saliba V, Legido-Quigley H, Hallik R, Aaviksoo A, Car J, McKee M. Telemedicine across borders: A systematic review of factors that hinder or support implementation. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81:793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]