Abstract

Tuberculosis is a common disease in developing countries such as India, posing a major public health problem. With human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection being a global endemic, there has been a resurgence of tuberculosis even in developed countries. Tuberculosis may affect almost any part of the body. However, tuberculosis of the calvarium is very rare. Presentation of tuberculosis as a soft tissue swelling on the scalp poses a diagnostic problem. These two cases are being reported here to convey the utility of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in providing the confirmatory diagnosis obviating the need for invasive surgical procedure.

Keywords: Calvarial tuberculosis, fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), scalp, Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain

Introduction

Calvarium tuberculosis is a very rare entity accounting for 0.2-1.3% of all cases of skeletal tuberculosis.[1] This has been attributed to the deficiency of lymphatics in the calvarial bones, thereby significantly reducing the chances of spread from the primary focus.[2] As the disease is very uncommon, the treating doctors usually do not consider it in the primary list of differential diagnosis of cystic scalp swelling. The disease is usually diagnosed during the process of carrying out an investigation for the disease. Mehrotra et al.[3] were the first to diagnose calvarial tuberculosis on fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Case 1

A 25-year-old male belonging to the low socioeconomic strata presented with a painful, soft tissue swelling on the scalp of 3 months duration. The swelling had gradually increased in size with mild pain. The pain was dull and localized to the lesion. There was no history of trauma. The patient had a history of rise of temperature in the evening, weakness, decreased appetite, headache, and giddiness for the last 1 month. The patient had a past history of cervical tubercular lymphadenitis 2 years ago, which was treated by antitubercular therapy for a period of 9 months. For the current problem, the patient had received a short course of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs but there was no improvement. The patient was known to be human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 positive and had been on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the last 3 years.

On local examination, there was single, nonpulsatile, cystic, nontender scalp swelling measuring 3 × 3 cm over the posterior-superior part of the skull. The skin over the swelling was essentially normal without any signs of acute or chronic inflammation. There were no sinuses or induration. Cough impulse was also absent. Clinically differential diagnoses of sebaceous cyst or lipoma or adenexal tumors of the skin were considered.

Systemic examination revealed multiple bilateral cervical lymph nodes of sizes ranging from 2 × 2 cm to 1 × 1 cm. Healed puckered sinuses were seen on the right side in the neck.

Routine haematological examinations including total leukocyte counts and differential leukocyte counts were within normal limits. However, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised, which was 40 mm in the first hour (Westergren's method). At the time of presentation, the CD4 count was within normal limits.

Radiological examination

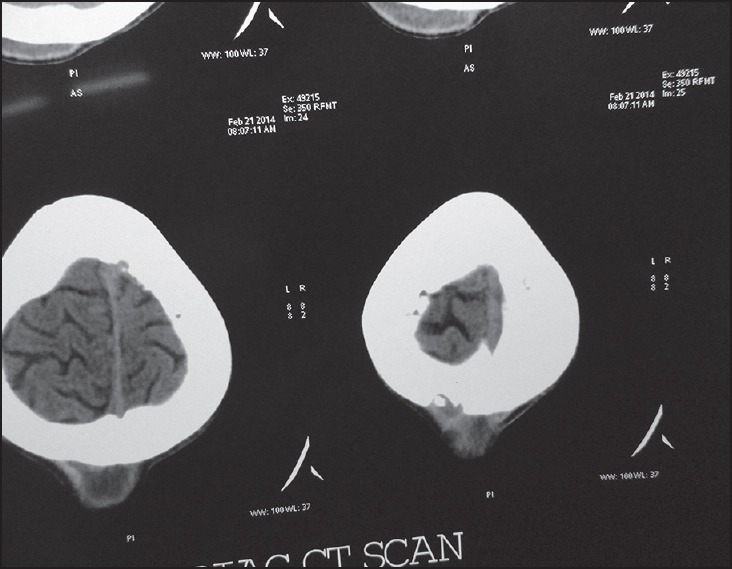

The chest x-ray was normal. X-ray of the lateral view of the skull showed a soft tissue swelling over the posterior superior aspect but there was no obvious bony lesion. The computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed bony erosion of posteriosuperior part of the outer table of parietal bone of the skull. The soft tissue mass was overlying the bony lesion [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan showing involvement of the outer table, along with soft tissue mass in case 1

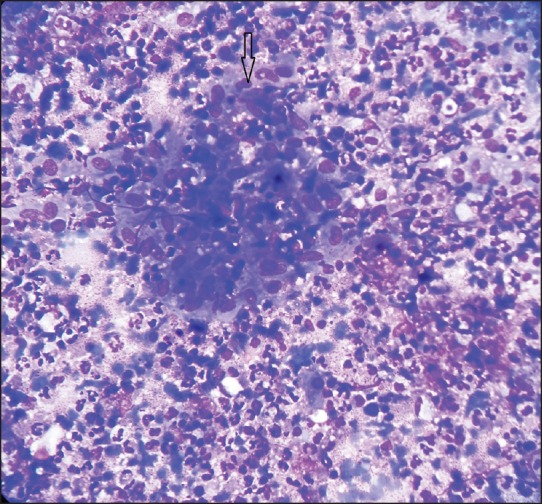

Cytological examination

Fine needle aspiration of the swelling was carried out using 22 gauze needle. It yielded yellowish purulent exudates. Giemsa stained smears showed epithelioid cell granuloma in background of inflammatory cells [Figure 2]. The Zeihl-Neelsen (ZN) stained smear showed the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB). A final diagnosis of tuberculosis of the skull was made.

Figure 2.

FNAC smear showing epithelioid cell granuloma (marked at arrow) in the background of inflammatory cells in case 1. (Giemsa stain, ×400)

Follow-up

The patient was put on antituberculous treatment (ATT) by the treating physician. The regular follow-up in ART clinic has shown significant clinical improvement in symptoms and signs of the disease in the patient.

Case 2

A young male of 20 years of age presented with a small swelling over the superior part of the scalp. The swelling was painful with a dull aching pain being present throughout the day. The patient noticed the swelling about 4 months ago. The swelling had been gradually increasing in size for the last 1 month, which prompted him to take medical opinion. The patient did not have any history of fever, weakness, weight loss, decreased appetite, headache, giddiness, or trauma. There was no history of steroid intake. The patient had a past history of tuberculosis of cervical lymph nodes in his early childhood for which he had received antitubercular therapy for a duration of 9 months. All routine haematological examinations were normal except for raised ESR (104 mm in the first hour). The patient was HIV-negative. Clinically, the differential diagnosis of sebaceous cyst, lipoma, or an adenexal tumor of the skin was considered by the treating doctor. The patient was referred to the department of pathology for FNAC.

On examination, there was a single, nonpulsatile, cystic, nontender swelling measuring 3 × 5 cm over the superior part of skull [Figure 3]. There were no signs of inflammation over the swelling. No sinuses were present. Cough impulse was absent. On deep palpation, eroded bony margins of the scalp could be palpated. Systemic examination was normal.

Figure 3.

Clinical picture of case 2

Radiological examination

The chest x-ray was normal. X-ray of the skull showed a soft tissue swelling, along with evidence of eroded, irregular skull bone. CT scan of the head was carried out before FNAC, in view of clinical suspicion of swelling being deep due to the presence of eroded bony margins under the swelling. The CT scan revealed a bony erosion of the outer table of the skull bone with soft tissue mass on it. The inner table of the skull bone was intact.

Cytological examination

The FNAC of the swelling was carried out using a 22G needle. It yielded pus-like material. Giemsa-stained smears revealed multiple epithelioid giant cell granulomas, along with focal caseous necrosis and Langhans giant cells. The ZN stain of the smear showed AFB. A final diagnosis of tuberculosis of the skull was made.

Follow-up

The patient was put on ATT by the treating physician as per the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. The patient has significant clinical improvement at the follow-up clinic.

Discussion

With the advent of AIDS and multidrug resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, there has been a resurgence of tuberculosis all over the world.[4] The skeletal tuberculosis accounts for 1% of the cases of tuberculosis[5] but only 0.2-1.3% among them accounts for tuberculosis of the skull bones.[1,6] Thus, calvarial tuberculosis is a rare manifestation of skeletal involvement by tuberculosis. Isolated calvarial tuberculosis is extremely rare. The disease is usually secondary to primary tubercular infection at other sites such as lungs, bones, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and the central nervous system.[1,7,8,9,10,11] The pathogenesis of calvarial tuberculosis starts with hematogenous seeding of the bacilli to the marrow of diploe from the extracalvarial focus. Depending on the immune status of the patient, the bacilli proliferate. Low immunity in immunodeficiency patients increases the virulence of the organism and increases the bacillary load. This further leads to infection spreading toward both the tables, causing destruction of bones and formation of granulation tissue by replacement of bony trabeculae. Normally, proliferation of fibroblasts in concentric layers contains the infection but low immunity prevents this. This causes the infection to spread to the outer table, which presents as a soft tissue swelling or as discharging sinuses, whereas spread of infection to the inner table and its further extension causes extradural granulation tissue formation. A combination of both of these is common. A good immune status of the patient slows down the evolution of the lesion.

Calvarial tuberculosis is rare and usually presents with pain and discharging sinus. Batuk Diyora[12] in their study of 11 cases reported pain and presence of sinus to be the most common feature at the time of presentation. Jadhav and Palande[13] also reported pain and discharging sinuses as the commonest presentation of the disease. However, in both of our patients, the presenting symptoms were gradually increasing cystic swelling over the posterior superior part of scalp with dull pain, without any signs of acute or chronic inflammation. Both the patients did not have any sinus or any skin change present over the swelling. While the first patient was HIV-positive and on ART, the second patient was not immune-compromised. However, both these patients had past history of being treated with full course of ATT for tubercular lymphadenitis. There are only a few reports of calvarial tuberculosis in HIV-positive cases (immuno-compromised cases) available in the literature. Tripathi et al. reported a case of calvarial tuberculosis in a HIV-positive patient, having multiple cystic lesions involving the frontal bone and parietal bones. On palpation of the swelling, the underlying bone margins could be felt.[13] Punched out bony defects as revealed by CT scan has also been reported by other authors in calvarial tuberculosis.[12] Our first patient seemed to have calvarial involvement but unlike cases where the calvarial bone destruction is so significant that it is possible to clinically feel for the eroded bone margins, we could not feel the margins of bones of the skull on palpation. This might be because the patient on regular follows-up in the ART clinic reported early for this complaint. However, in our second patient, on clinical examination, the eroded bone margins were easily noticeable on palpation. This might have been due to the patient having neglected himself in the initial stage of the disease and having reported only after 4 months of the onset of the lesion.

Both our patients had past history of tubercular cervical lymphadenitis for which they were adequately treated by ATT. This was evident by the presence of healed sinuses on the right side of the neck in the first patient. However, in the second patient, no visible stigma of disease in the form of a scar or healed sinus was present. The presence of bilateral lymph nodes varying in size from 2 × 2 cm to1 × 1 cm at the time of presentation in the first patient could have been due to reactivation of old tubercular focus and that could have acted as a primary focus of tuberculosis. These cervical lymph nodes were not matted. FNAC from these lymph nodes was positive for epithelioid cell granulomas but no AFB was seen. The lesion in the skull could have been been secondary to cervical tubercular lymphadenitis in the first patient. The available literature also suggests that calvarial tuberculosis is mostly secondary to lesions elsewhere in the body. However, our second patient did not have any evidence of reactivation of the disease or any other tubercular focus elsewhere in the body and primary source of the disease could not be identified.

Calvarial tuberculosis is most common in young patients with 70-90% cases occurring in the age below 20 years.[1,10] Batuk Diyora et al. suggested a male preponderance,[12] whereas Jadhav et al. suggested a female predominance.[13] Abhijit et al. in a retrospective study of 42 cases, reported a male to female ratio of 2:1 with the mean age of 16 years and involvement of parietal bone in 54.4% of the cases.[14] Both of our patients were young adult males where the parietal bone was involved.

Tubercular lesions of the bone usually involve cancellous bones.[1] The frontal and parietal bones have more cancellous bone than other areas of the skull. Hence, these are the most common sites of infection. In both of our patients, the outer table of the parietal bone was involved. There was no CT evidence of involvement of the inner table or any intracranial extension in either of the patients. There was no sequestrum either. Most authors recommend CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lesion to assess the extent of bone involvement, scalp swelling, degree of intracranial extension, and presence of sequestrum, which help in further planning the treatment.[12,14,15,16]

After the CT findings suggested the osteomylitis of the parietal bone with the intact inner table, FNAC was planned out for these two patients. It was carried out using a 22G needle. The smears were stained with Giemsa stain and ZN stain. The presence of AFB in FNAC smears established the diagnosis of tuberculosis in our patients. AFB culture facilities were not available at our center.

Reports available in the literature show that patients usually report late for this disease. They usually require surgeries in the form of excision of dead and necrotic tissues, removal of sequestrum, closure of defects, etc., along with ATT.[12,13] As both of our patients reported early and the inner table of the skull was intact in both the cases without any evidence of sequestrum or intracranial extension of the abscess, the treating doctor in the patient's interest decided against biopsy or any surgical intervention. The early timely diagnosis by FNAC obviated the need of an operative interference in both of our patients. Malhotra et al.,[3] also emphasized the importance of FNAC in obviating the need of surgical procedures in cases of calvarial tuberculosis.

Conclusion

A soft tissue, cystic, swelling on the scalp is associated with a variety of clinical differentials such as sebaceous cyst, lipoma, adenexal tumor, solitary myeloma of the bone, secondary metastasis. As calvarial tuberculosis is very uncommon, it is only a rare possibility. Thus, a high index of suspicion is required for prompt diagnosis of this condition. The two patients with contrast immune status (one being HIV-positive and on ART and the other with no evidence of being immune-compromised) presenting with almost similar clinical presentations highlight the unpredictable presentation of the disease. Based on the clinical history, radiological investigations supported by FNAC findings of the cervical lymph nodes, along with HIV positive status, the treating physician advised FNAC of the scalp lesion in the first case. On the other hand, in the second patient, a positive past history of tuberculosis, raised ESR, clinical examination, and CT scan findings were the reasons behind carrying out FNAC. The FNAC picture of the lesions in both the cases, along with the AFB positivity, confirmed the diagnosis. This helped in timely treatment and prevention of further complications. Both the patients were managed by ATT alone, obliviating the need for any surgical intervention.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study is from the Department of Pathology, Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar (B.S.A) Hospital, Rohini, Delhi (India), which is run by the Government of Delhi.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Strauss DC. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of vault of the skull. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;57:384–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awasthy N, Chand K, Singh A. Calvarial tuberculosis: Review of six cases. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2006;9:227–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra R, Sharma K. Cytodiagnosis of tuberculosis of the skull by fine needle aspiration cytology: A case report. Pathology. 2000;32:213–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts HG, Lifeso RM. Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:288–98. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199602000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson PT, Horowitz I. Skeletal tuberculosis. A review with patient presentations and discussion. Am J Med. 1970;48:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(70)90101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tirona JP. The roentgenological and pathological aspects of tuberculosis of the skull. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1954;72:762–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton CJ. Tuberculosis of the vault of skull. Br J Radiol. 1961;34:286–90. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-34-401-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tata HR. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of the skull. Indian J Tuberculosis. 1978;25:208–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng CM, Wu YK. Tuberculosis of the flat bones of the vault of the skull. J Bone Joint Surg. 1942;34:341–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohanty S, Rao CJ, Mukherjee KC. Tuberculosis of the skull. Int Surg. 1981;66:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra SK, Nigam P. Tuberculosis of flat bones. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1984;26:174–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diyora B, Kumar R, Modgi R, Sharma A. Calvarial tuberculosis: A report of eleven patients. Neurol India. 2009;57:607–12. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.57814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadhav RN, Palande DA. Calvarial tuberculosis. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:1345–50. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raut AA, Nagar AM, Muzumdar D, Chawla AJ, Narlawar RS, Fattepurkar S, et al. Imaging features of calvarial tuberculosis: A study of 42 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:409–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripathi AK, Gupta N, Khanna M, Ahmad R, Tripathi P. Tuberculosis presenting as osteolytic soft tissue swellings of skull in HIV positive patient: A case report. Indian J Tuberc. 2007;54:193–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safia R, Zeeba J, Sujata J. Calvarial Tuberculosis: A rare localisation of a common disease. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2013;6:309–11. [Google Scholar]