Abstract

Introduction:

Imbalance in cellular metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids is observed in diabetes mellitus. Pancreatic α-amylase and α-glucosidases are responsible for the conversion of polysaccharides into glucose that enters in the blood stream. Triphala has shown antidiabetic effects (type 2) in human subjects. However, its effects on glycolytic enzymes and protein glycation have not been studied.

Aim:

To evaluate glycolytic enzyme inhibitory and antiglycation potential of Triphala.

Materials and Methods:

Triphala Churna was extracted with cold water and subjected to phytochemical analysis. Studies on α amylase and α glucosidase inhibition were performed, and its antiglycation potential was determined.

Results:

Triphala extract showed prominent α-amylase inhibitory potential (48.66% at concentration 250 μg/ml). Percent α-glucosidase inhibition increased with increasing concentration of the extract (6.32–40.64%). Extract showed remarkable results for antiglycation potential. Triphala extract showed glycation inhibition by inhibiting fructosamine; fructosamine inhibition was found to be 37.74%, protein carbonyls were inhibited up to 15.23% whereas protein thiols were inhibited up to 84.81%.

Conclusion:

Triphala showed glycolytic enzyme inhibitory and antiglycation potential. Hence, it can be effectively used in the diabetes management.

Keywords: α-Amylase, α-glucosidase, antiglycation, diabetes, Triphala

Introduction

Triphala, a rejuvenating drug mentioned in Ayurveda, is one of the most common and economical medicinal preparations accessible in India. It is regarded as a therapeutic agent having balancing and revivifying effects on three humors as per Ayurveda viz. Vata, Pitta and Kapha. Triphala consists of equal portions of three medicinal herbs as, Indian Gooseberry (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.), Chebulic Myrobalan (Terminalia chebula Retz.), and Beleric Myrobalan (Terminalia bellerica Gaertn.).[1,2]

In the modern era, a number of researches have been performed on Triphala that has established antioxidant and revitalizer[3,4] anti-diarrhoeal[5] and antiobesity[6] effects of Triphala.

Imbalance in cellular metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids is observed in noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Such a condition predisposes to increase in postprandial blood glucose levels.[7,8] During type 2 diabetes mellitus, a sudden rise in blood glucose levels is observed that is contributed due to starch hydrolysis by pancreatic α-amylase and glucose uptake by α-glucosidase.[9]

Enzyme pancreatic α-amylase is the main enzyme, which plays a key role in starch hydrolysis and converts them into small oligosaccharides. These are then further catalyzed by α-glucosidase that convert them into glucose that after absorption enters into the blood stream. This process ensues in haste that ultimately predisposes the condition of postprandial hyperglycemia. Thus, impeding the process of digestion of starch could play a vital role in the management of diabetes.[10] Drugs such as acarbose, voglibose, and miglitol are known to inhibit glycolytic enzymes. However, their nonspecific response and adverse effects like abdominal discomfort and diarrhea[11] restrict their frequent use. Use of herbal remedies seems to be a promising approach in the treatment of diabetes in terms of no or less side effects and economical.[12]

A number of plant derived polyphenols are known to demonstrate antiobesity and antidiabetic effects by virtue of the inhibiting activity of enzymes such as lipase and α-glucosidase.[13,14,15] Triphala has also shown antidiabetic effects (type 2) in human subjects.[16] However, its effects on glycolytic enzymes and protein glycation have not been studied. Hence, the aim of the present work was to evaluate glycolytic enzyme inhibitory and antiglycation potential of Triphala.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

The various chemicals used in this study includes porcine pancreatic amylase (PPA), gallic acid (SRL, Mumbai), acarbose (Bayer Pharmaceutical), trichloro acetic acid, ascorbic acid (Merck, Mumbai), ammonium molybdate (Qualigens, Mumbai), 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (Loba Chemie, Mumbai). Triphala Churna was purchased from local market.

Extraction

A total of 50 g of Triphala powder was extracted with 100 ml distilled water (cold perfusion) for 6 h. The extract was then filtered and concentrated. The extract was subjected to phytochemical analysis as per reported method.[17]

Glycolytic enzyme inhibition studies

α-Amylase inhibitory assay

Porcine pancreatic amylase inhibitory assay was performed by following standard method.[18] About 2 mg of starch was suspended in each of the tubes containing 0.2 ml of 0.5 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.9) and 0.01 M CaCl2. The tubes containing the substrate solution were boiled for 5 min and were then incubated at 37°C for 5 min. About 0.2 ml of extract was taken in each tube containing different concentrations (10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/ml) of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). PPA was dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer to form a concentration of 2 units/ml and 0.1 ml of this enzyme solution were added to each of the above mentioned tubes. The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 10 min and was stopped by adding 0.5 ml of 50% acetic acid in each tube. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1700 spectrometer). The α-amylase inhibitory activity was calculated as follows:

= [(Ac+) − (Ac−)] − [(As − Ab)]/[(Ac+) − (Ac−)] × 100,

where Ac+, Ac−-, As and Ab are defined as the absorbance of 100% enzyme activity (only solvent with enzyme), 0% enzyme activity (only solvent without enzyme activity), a test sample (with enzyme), and a blank (a test sample without enzyme), respectively.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity

The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined using the standard method.[19] The enzyme solution was prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg α-glucosidase in 10 ml phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 20 mg bovine serum albumin (BSA). It was diluted further to 1:10 with phosphate buffer just before use. Sample solutions were prepared by dissolving 4 mg sample extract in 400 μl DMSO. Five concentrations; 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 μg/ml were prepared and 5 μl each of the sample solutions or DMSO (sample blank) was then added to 250 μl of 20 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside and 495 μl of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). It was pre-incubated at 37°C for 5 min and the reaction started by addition of 250 μl of the enzyme solution, after which it was incubated at 37°C for exactly 15 min. 250 μl of phosphate buffer was added instead of enzyme for blank. The reaction was then stopped by addition of 1000 μl of 200 mM Na2CO3 solution, and the amount of p-nitrophenol released was measured by reading the absorbance of the sample against sample blank (containing DMSO with no sample) at 400 nm using UV–visible spectrophotometer.

Antiglycation potential

Glycation of bovine serum albumin

Albumin glycation was performed with certain modifications.[20] Glycated BSA samples were prepared with BSA (10 mg/ml) fructose (250 mM) in potassium phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.4 containing 0.02% sodium azide) with extract. These were incubated in the dark for 4 days at 37°C in sealed tubes. Positive control (BSA + fructose) was also maintained in similar conditions. All the incubates were made in triplicates. The unbound form of fructose in the solution was obtained by dialysis against the phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.4) and was stored at 4°C. The resultant obtained was used for determination of antiglycation activity of the extract by estimation of fructosamines adducts, protein carbonyls, protein thiols, and Congo red absorbance.

Estimation of fructosamine

Nitrobluetetrazolium assay was used for the determination of fructosamine.[21] About 0.8 ml of nitrobluetetrazolium (0.75 mM) in sodium carbonate buffer (100 mM, pH 10.35) was added to the aliquots of glycated samples and positive control (40 ml) and these were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the absorbance was taken at 530 nm and percent inhibition of fructosamines by extract was calculated by –

Inhibitory activity (%) = [(A0 − A1)/A0] × 100

where A0 is the absorbance value of the positive control and A1 is the absorbance of the glycated albumin samples co-incubated with extract.

Carbonyl group estimation

For protein carbonyls, absorbance was taken at 365 nm and the concentration was calculated by molar extinction coefficient.[22] The results obtained were given as percentage inhibition and was calculated by the formula used in the estimation of fructosamine.

Protein thiol estimation

The estimation of thiol groups of glycated albumin samples and positive control was performed by dithionitrobenzoic acid (DTNB).[23] In this assay, 250 µl samples and control were incubated with three volumes of 0.5 mM-DTNB (750 µl) for about 15 min and then the absorbance was taken at 410 nm. The free thiol concentration in the solution was taken by the standard curve of various BSA concentrations (0·8–4 mg/ml) as nM thiols/mg protein. The percentage protection was calculated by the formula used in the estimation of fructosamine.

Binding of Congo red

Congo red binding was measured by taking the absorbance at 530 nm.[24] For this assay, the samples (500 µl) were incubated with 100 µl of Congo red (100 µM) in phosphate-buffered saline with 10% (v/v) ethanol for 20 min at room temperature. The absorbance was recorded for both Congo red incubated samples as well as for Congo red background. The results were expressed as percentage inhibition calculated by the same formula used in estimation of fructosamine.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Experiments were always performed in triplicates. Statistical comparison was performed using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's test (P < 0.001).

Results

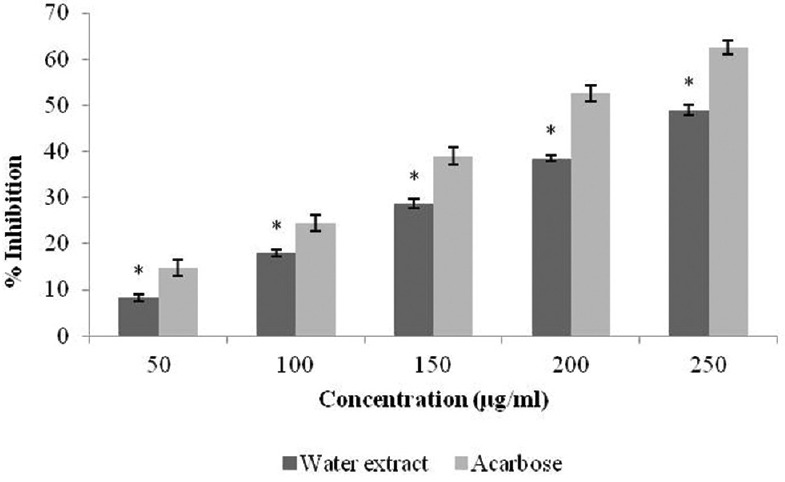

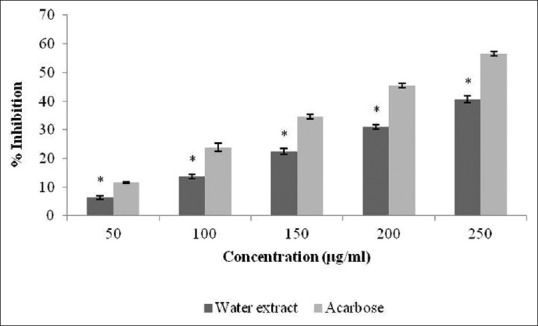

Triphala extract was found to be rich in tannins, polyphenols, alkaloids, and glycosides. The percentage yield was 5.4%. The present work was focused to establish the inhibitory activity of Triphala against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. The percentage inhibition displayed by each extract [Figure 1], which justifies that Triphala extract showed prominent α-amylase inhibitory potential (48.66% at concentration 250 μg/ml). This percentage of inhibition ranged from 8.23 to 48.66. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of Triphala extract is shown in Figure 2. For all tested concentrations, percent α-glucosidase inhibition increased with increasing concentration of the extract. Inhibition in enzyme activity ranged from 6.32% to 40.64%.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory activity of Triphala extract against α-amylase. The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Statistical comparison was performed using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's test (*P < 0.001)

Figure 2.

Inhibitory activity of Triphala extract against α-glucosidase. The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Statistical comparison was performed using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's test (*P < 0.001)

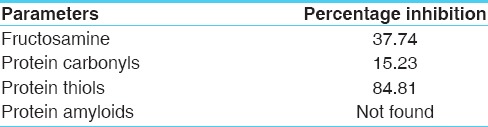

In glycation inhibitory activity, extract showed remarkable results for antiglycation potential. For inhibition of glycation potential inhibition, the various parameters were calculated like fructosamine inhibition was found to be 37.74%, protein carbonyls were inhibited up to 15.23% whereas protein thiols were inhibited up to 84.81% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Percentage inhibition of different glycated proteins at 33 mg/ml concentration by Triphala extract

Discussion

According to the International Diabetes Federation, type-2 diabetes presently has an effect on 246 million people globally and is anticipated to augment to 380 million by 2025. Type-2 diabetes is observed as impairment in glucose tolerance, elevated cholesterol and blood pressure predisposing to cardiovascular risk.[25] Thus, it becomes necessary to search some safe drugs against such condition. As per World Health Organization, >80% of the world's population depends on traditional medicine and folklore for healthcare. Use of herbal remedies in Asian subcontinent depicts a long history of use of medicinal plants for maintenance of good health. The use of herbal medicines in Asia represents a long history of human interactions with the environment. Plants used for traditional medicine contain a wide range of substances that can be used to treat chronic, as well as infectious diseases.[26]

Administration of Triphala for a period of 45 days, produces a significant reduction in blood glucose levels.[16] Current study aimed to determine the effect of Triphala on activity of glycolytic enzymes as α-amylases and α-glucosidase along with protein glycation studies. In this work, Triphala extract significantly inhibited (P < 0.01) activity of amylase and glucosidase. It was observed that nonenzymatic glycation in between proteins and reducing sugars leads to the formation of advanced glycation products. Such products are believed to progress pathogenesis of diabetic and aging complications.[27] Hence, inhibition of such glycation end products may demonstrate a key role in inhibiting diabetic complications. Some previous reports pertaining to antiglycation effects of polyphenols have been established.[28,29] Triphala extract effectively inhibited protein glycation which is contributed due to presence of tannins.

Conclusion

Triphala extract demonstrated α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory potential which may serve as a lead for isolation and identification of compounds responsible for it. However, more systematic studies are needed to confirm these results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Authors are thankful for Rewa Shiksha Samiti for providing grant for research purpose.

References

- 1.Sandhya T, Lathika KM, Pandey BN, Mishra KP. Potential of traditional ayurvedic formulation, Triphala, as a novel anticancer drug. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2nd English ed. New Delhi: Controller of Publications, Ministry of H, F and W, Govt. of India; 2003. The Ayurvedic Formulary of India, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srikumar R, Parthasarathy NJ, Manikandan S, Narayanan GS, Sheeladevi R. Effect of Triphala on oxidative stress and on cell-mediated immune response against noise stress in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;283:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-2271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagetia GC, Baliga MS, Malagi KJ, Sethukumar Kamath M. The evaluation of the radioprotective effect of Triphala (an ayurvedic rejuvenating drug) in the mice exposed to gamma-radiation. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:99–108. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biradar YS, Singh R, Sharma K, Dhalwal K, Bodhankar SL, Khandelwal KR. Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal property and acute toxicity of Triphala Mashi, an Ayurvedic formulation. J Herb Pharmacother. 2007;7:203–12. doi: 10.1080/15228940802152869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurjar S, Pal A, Kapur S. Triphala and its constituents ameliorate visceral adiposity from a high-fat diet in mice with diet-induced obesity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012;18:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriksen EJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, Marchionne EM. Oxidative stress and the etiology of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruenwald J, Freder J, Armbruester N. Cinnamon and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:822–34. doi: 10.1080/10408390902773052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon YI, Apostolidis E, Kim YC, Shetty K. Health benefits of traditional corn, beans, and pumpkin: In vitro studies for hyperglycemia and hypertension management. J Med Food. 2007;10:266–75. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichler HG, Korn A, Gasic S, Pirson W, Businger J. The effect of a new specific alpha-amylase inhibitor on post-prandial glucose and insulin excursions in normal subjects and Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1984;26:278–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00283650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng AY, Fantus IG. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. CMAJ. 2005;172:213–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee PK, Maiti K, Mukherjee K, Houghton PJ. Leads from Indian medicinal plants with hypoglycemic potentials. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;106:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei F, Zhang XN, Wang W, Xing DM, Xie WD, Su H, et al. Evidence of anti-obesity effects of the pomegranate leaf extract in high-fat diet induced obese mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1023–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanamura T, Mayama C, Aoki H, Hirayama Y, Shimizu M. Antihyperglycemic effect of polyphenols from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC.) fruit. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1813–20. doi: 10.1271/bbb.50592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yajima H, Noguchi T, Ikeshima E, Shiraki M, Kanaya T, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, et al. Prevention of diet-induced obesity by dietary isomerized hop extract containing isohumulones, in rodents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:991–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajan SS, Antony S. Hypoglycemic effect of triphala on selected non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus subjects. Anc Sci Life. 2008;27:45–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harborne JB. Phytochemical Method: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plants Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1983. pp. 4–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansawasdi C, Kawabata J, Kasai T. Alpha-amylase inhibitors from roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn.) tea. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:1041–3. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutedja L. Funct Food Prod Technology. 1st ed. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem; 2005. Bioassay of antidiabetes based on α-glucosidase inhibitory activity; pp. 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPherson JD, Shilton BH, Walton DJ. Role of fructose in glycation and cross-linking of proteins. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1901–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00406a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker JR, Zyzak DV, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Chemistry of the fructosamine assay: D-glucosone is the product of oxidation of Amadori compounds. Clin Chem. 1994;40:1950–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida K, Kanematsu M, Sakai K, Matsuda T, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, et al. Protein-bound acrolein: Potential markers for oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4882–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klunk WE, Jacob RF, Mason RP. Quantifying amyloid by Congo red spectral shift assay. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:285–305. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haffner SM. The insulin resistance syndrome revisited. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:275–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duraipandiyan V, Ayyanar M, Ignacimuthu S. Antimicrobial activity of some ethnomedicinal plants used by Paliyar tribe from Tamil Nadu, India. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suresh Babu K, Tiwari AK, Srinivas PV, Ali AZ, China Raju B, Rao JM. Yeast and mammalian alpha-glucosidase inhibitory constituents from Himalayan rhubarb Rheum emodi Wall.ex Meisson. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3841–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SY, Jung SH, Lee HS, Park KW, Yun BS, Lee KW. Glycation inhibitory activity and the identification of an active compound in Plantago asiatica extract. Phytother Res. 2008;22:323–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun C, McIntyre K, Saleem A, Haddad PS, Arnason JT. The relationship between antiglycation activity and procyanidin and phenolic content in commercial grape seed products. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:167–74. doi: 10.1139/y11-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]